Abstract

Attic cholesteatoma with antral extension in tight sclerotic mastoid cavities is a common presentation that creates difficult decision-making intraoperatively. Drilling through a sclerotic and small mastoid cavity, keeping the canal wall intactis often difficult and increases the risk of serious injury. Consequently, a canal-wall-down mastoidectomy is often performed. The endoscopic transcanal modified canal-wall-down mastoidectomy approach allows the benefits of an open cavity for cholesteatoma resection and the benefits of a closed cavity for better long-term care and a more normal ear canal and middle ear reconstruction.

Keywords: Cholesteatoma, Inside-out technique, Attico-antrotomy, Sclerotic mastoid, Attic obstruction, Middle ear cholesteatoma, DWI MRI, Propeller MRI for cholesteatoma, Ossicular chain reconstruction, Cartilage repair of attic

Introduction

One of the most common presentations of temporal bone cholesteatoma is secondary acquired attic cholesteatoma.1 Left untreated, attic cholesteatoma often spreads into the antrum and mastoid as it engulfs the ossicles and extends into the hypotympanum and sinus tympani. Early in its presentation, attic cholesteatoma can be found confined to the Prussak's space of the epitympanic recess and lateral to the malleus and incus.

For decades, otologic surgeons have felt uncomfortable operating on early attic cholesteatoma with no clinical symptoms, especially if the hearing was normal, lest surgery would make the patient worse. Surgeons would tell patients to keep observing the cholesteatoma and intervene if the ear drained or developed more “significant” conductive hearing loss. This was usually because the traditional microscopic approaches require extensive and difficult drilling of dense sclerotic mastoids, often with removal of ossicles, and thus causing maximum conductive hearing loss. For theses reasons and more, many earlier surgeons shunned away from operating on asymptomatic “early” attic cholesteatoma. However, early attic cholesteatoma is best treated before it extends out of the epitympanic recess and the endoscopic approach provides the best platform for ossicular preservation.2

Once cholesteatoma spreads beyond the epitympanic recess, it engulfs the head of the malleus, malleus-incus joint and the Cog area. Subsequently, cholesteatoma erodes and passes through the anterior superior ligament of the malleus, extending into the antrum. After crossing the antrum, there is no resistance to the spread of cholesteatoma into any and all aerated mastoid air cells. At this later stage, endoscopic atticotomy would not be sufficient and the antrum or the mastoid cavity need to be opened up. This is where the decades old controversy starts: Should the mastoid extension of disease be addressed using a canal-wall-up or a canal-wall-down approach. Many modifications to each approach have been utilized over the years.3, 4

The main problem is that attic and antral cholesteatoma is often associated with densely sclerotic mastoids with minimal to no aeration. Consequently, drilling from the outer mastoid cortex to the antrum is often very difficult and tedious, making conventional postauricular intact canal wall mastoidectomy in such sclerotic mastoids undesirable and fraught with potential serious complications, such as tegmen or lateral semicircular canal labyrinthine injury and, in rare cases, injury to the facial nerve or sigmoid sinus.

Thus, the preferred surgical approach, in tight sclerotic mastoid cavities with attic cholesteatoma, has been to proceed with a canal-wall-down mastoidectomy, resection of the attic cholesteatoma and leaving either a large or small, obliterated mastoid cavity to heal.5 This is a fine operation in competent hands and should result in a relatively small and even sometimes self-cleaning mastoid cavity. However, we all have seen and taken care of poorly epithelized and draining mastoid cavities, or those that collect huge amounts of keratin debris and must be cleaned professionally on a regular basis every few months.

Canal-wall-down mastoid cavities are not “physiologic” and most, if not all, need professional care for the life of the patient. Especially large or poorly done mastoid cavities end up needing routine annual or semiannual mastoid cavity cleaning lifelong. Patients have to prevent water exposure and wear earplugs in the shower or when swimming. To avoid such lifelong issues, surgeons either attempt to do an intact canal wall mastoidectomy in tight sclerotic mastoids, or do a canal-wall-down mastoidectomy with obliteration of most of the mastoid cavity.6

Numerous remedies have been offered for decades, for mastoid obliteration in these cavities. All previous attempts at these remedies have required either a postauricular or an endaural incision and have required extensive drilling in dense bone before reaching the antrum where the disease often resides and “hides”.7

In this paper, a new twist to an old approach is offered. The Endoscopic transcanal modified canal-wall-down mastoidectomy (ETM-CWD) is a natural extension of the old “inside-out” technique. The old “inside-out” technique has been around for decades and has been largely forgotten in the era of intact canal wall mastoidectomy and canal wall preservations.8

However, in this version, the old “inside-out” attico-antrotomy resection is performed completely transcanal with one-handed drilling using high definition rigid video endoscopes. This approach allows for limited drilling to expose and remove cholesteatoma, and then repair the canal wall defect.

Materials and methods

The Endoscopic transcanal modified canal-wall-down mastoidectomy (ETM-CWD) surgical technique steps are as follows:

-

1.

A preoperative temporal bone computed tomography (CT) scan is mandatory when contemplating this approach, to evaluate the extent of the attic disease, the degree of mastoid pneumatization, the surgical anatomy and to formulate a plan of action.9

-

2.

If the CT scan shows a widely pneumatized mastoid with extensive soft tissue, then a traditional postauricular intact canal wall mastoidectomy, with or without endoscopic assistance, could be used safely and effectively, and would be preferred.10

-

3.

The ETM-CWD approach is best suited in cases where the mastoid antrum is involved with dense cholesteatoma and the entire mastoid outer cortex is sclerotic.

-

4.

A high definition 3-chip video camera system, with the high resolution 3 mm diameter, 14 cm long rigid endoscopes using zero, 45 and 70° angulation is utilized.

-

5.

Keep the light intensity output of the endoscope at 50% or less.

-

6.

Must have a complete set of endoscopic ear instruments, allowing access to far angled spaces.

-

7.

Hypotensive general anesthesia with systolic blood pressure around at or <90 mmHg and 90 mmHg and MAP of 75–80 mmHg.

-

8.

Keep patient's head elevated at 15–30° to reduce bleeding.

-

9.

Use of a facial nerve EMG monitor is highly advised.

-

10.

Meticulous injection of the ear canal, meatus and concha with 1% lidocaine with epinephrine 1:100,000 using a fine 27 gauge needle. Do not over-inject since the facial nerve could be affected.

-

11.

Use epinephrine-soaked cotton balls during ear canal flap elevation liberally.

-

12.

Standard incisions for the tympanomeatal flap are made at 6 and 12 o'clock positions with interconnection midway in the bony canal. Fig. 1.

-

13.

Extend the 6 and 12 o'clock incisions to the conchal bowl inferiorly and to the incisura superiorly. This is essentially similar to the classic Lempert one, two and three incisions of the endaural approach, but stopping superiorly at the incisura.8

-

14.

Raise the laterally based back flap, known as the Kerner's flap, all the way laterally to the conchal bowl. This is a crucial step in order to get ready for the canal-wall-down mastoidectomy.

-

15.

Use small fishhook retractors to keep the lateral flap out of the way of the shaft of the drill. Fig. 2.

-

16.

Raise the tympanomeatal flap medially under endoscopic vision, enter the middle ear space, and address the cholesteatoma via the standard endoscopic ear surgery techniques. Utilize specialized endoscopic ear surgery instruments here as needed. Fig. 3.

-

17.

Follow the cholesteatoma into the attic and antrum superiorly by curetting the scutum and performing an atticotomy as needed. Be prepared to do a type III atticotomy and more. Fig. 4.

-

18.

Once cholesteatoma is encountered beyond the type III atticotomy exposure, then the superior bony canal wall needs to be drilled and partially removed. Fig. 5, Fig. 6.

-

19

Use a quiet, electric otologic drill with a 2 mm extra course diamond burr under intermittent irrigation. Drilling could be difficult due to poor vision. Drilling is often done intermittently for a few seconds and then stop to irrigate and suction before drilling further. Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9.

-

20.

Protect the tympanomeatal flap out of drill's pathway by reflecting it anterior-inferiorly over the eardrum and covering it with a small cotton ballor a piece of aluminum foil.

-

21.

Curette the bony ear canal and scutum to expose the antrum. Must have full exposure of the tympanic portion of the facial nerve and the dome of the lateral semicircular canal (SCC) prior to any drilling. Fig. 10.

-

22.

The dome of the lateral SCC can be exposed by curetting the bony ear canal edge (scutum), exposing the fossa incudis and opening all the way toward the attic. It's best to avoid using a drill in this location. Fig. 11.

-

23

Start drilling at the superior edge of the atticotomy, being extremely careful not to allow the drill to “jump”. Drill toward the middle fossa tegmen in order to open up the antrum. Fig. 12, Fig. 13.

-

24.

Do not remove the inferior aspect of the bony ear canal below the chorda tympani nerve exit. There is usually no cholesteatoma there and the lateral SCC and the descending facial nerve would be at risk of injury. Furthermore, excessive bone removal inferiorly would make ear canal wall reconstruction very difficult, if not impossible.

-

25.

Harvest an appropriate length of either conchal or tragal cartilage to fill the bony canal defect by wedging the cartilage between the bony defect, thus preventing the cartilage from falling into the mastoid cavity. Use a small amount of tissue glue to secure the cartilage. Fig. 14.

-

26.

Use another piece of cartilage to cover the atticotomy defect resting next to the ossicles if present. Fig. 15.

-

27.

Use an extra long piece of temporalis fascia to cover the eardrum defect, the cartilage in the attic and the entire bony ear canal cartilage repair. Fig. 16, Fig. 17.

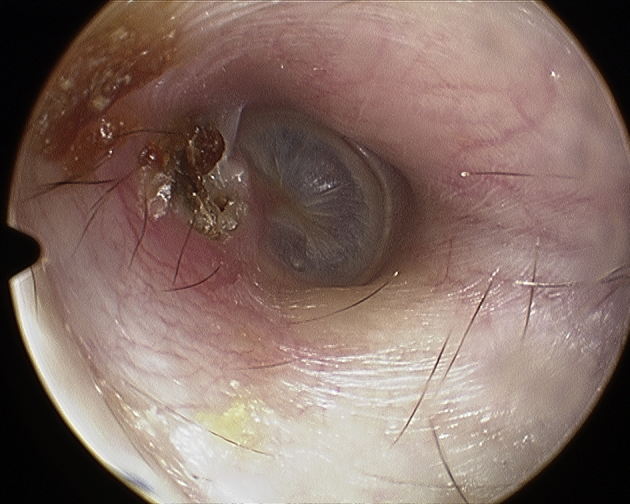

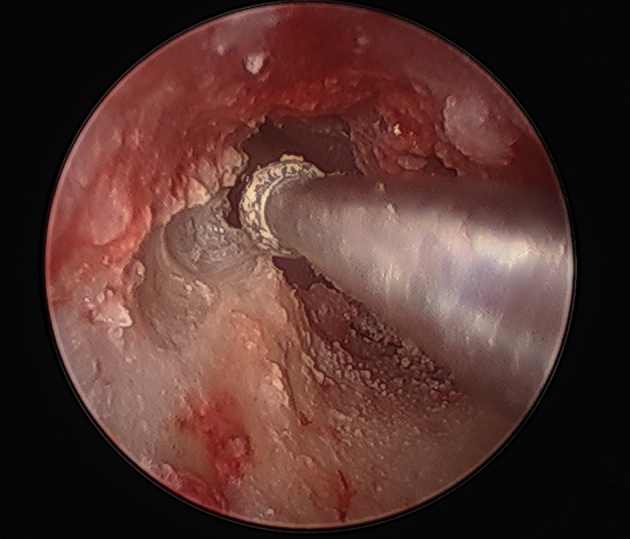

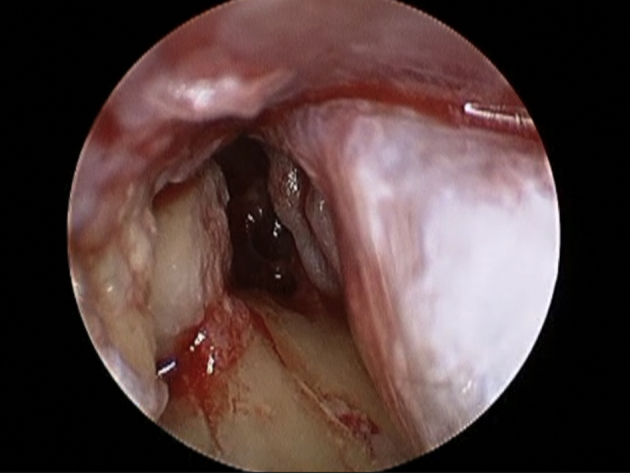

Fig. 1.

Attic cholesteatoma pre-op.

Fig. 2.

Fish hook skin retractor attached to concha on right ear.

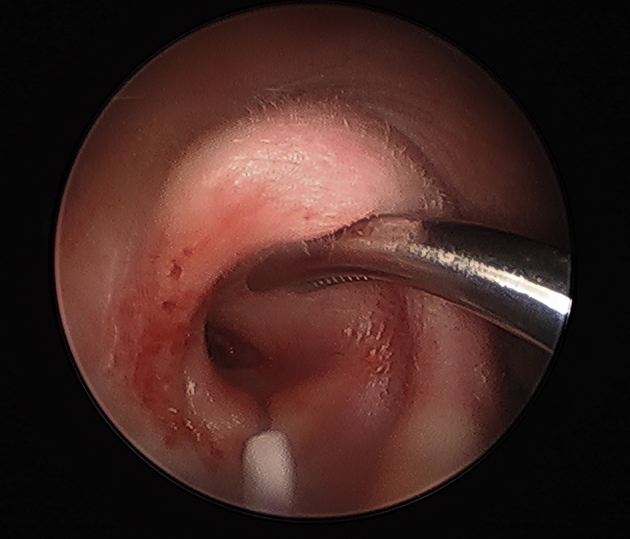

Fig. 3.

Tympanomeatal flap elevation with Lancet elevator approaching the annulus.

Fig. 4.

Atticotomy using curette to remove the scutum.

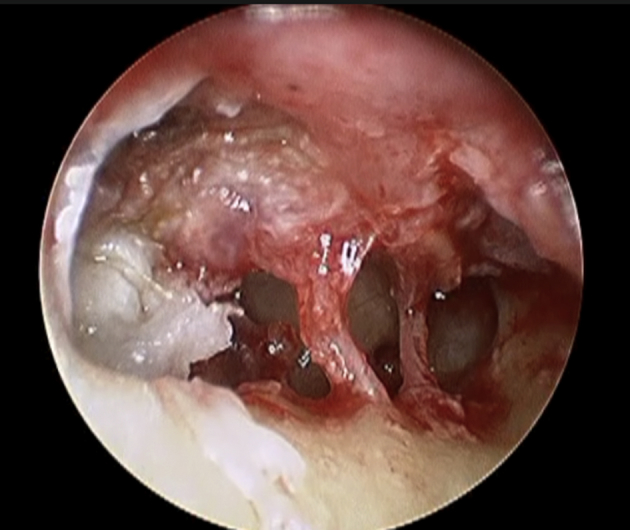

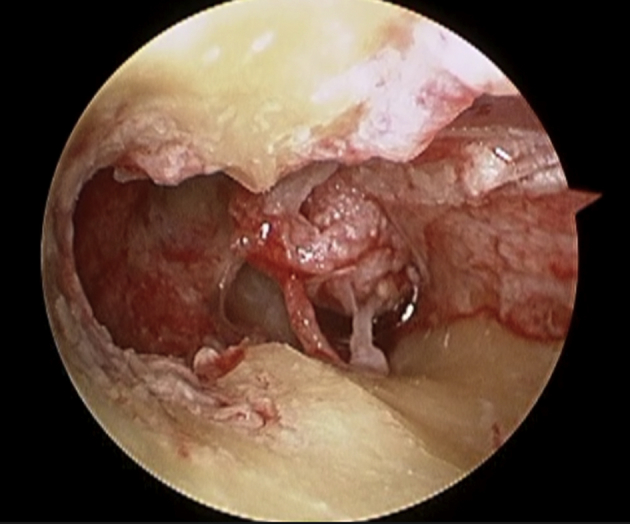

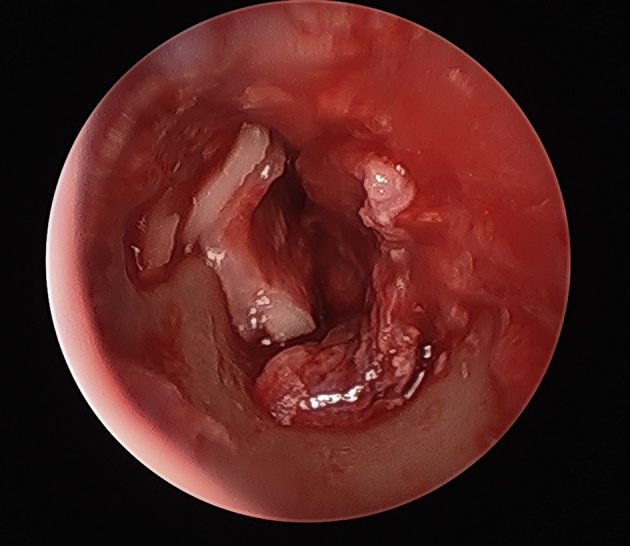

Fig. 5.

Cholesteatoma in the antrum after atticotomy has been done. Chorda tympani nerve is in the middle of the field, cholesteatoma engulfs and covers Incus. Right ear.

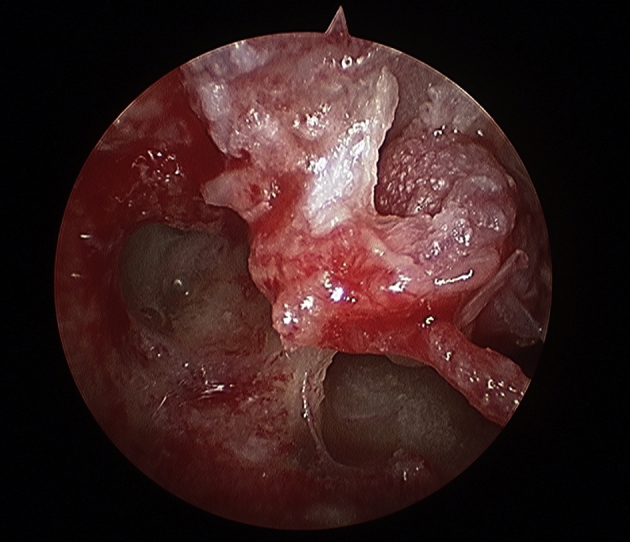

Fig. 6.

Type III atticotomy and resection of attic cholesteatoma exposing the cog and tensor tympani tendon coming off of cohlearoform process.

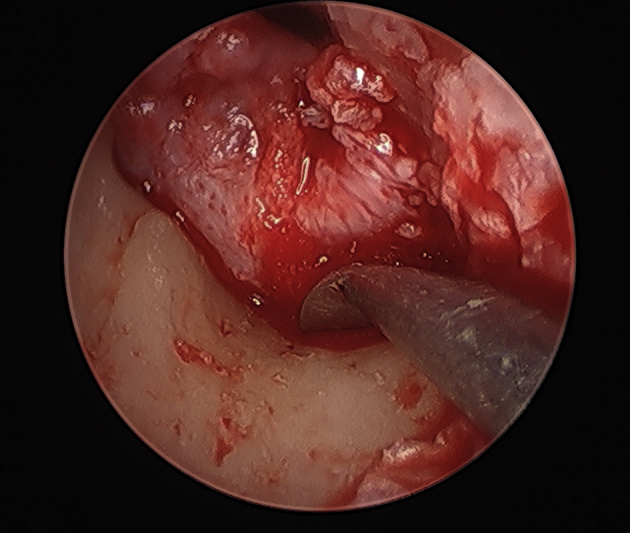

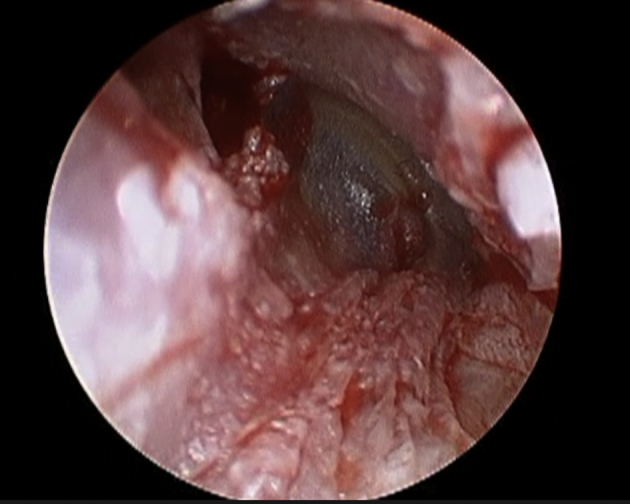

Fig. 7.

Beginning to drill into the antrum after atticotomy has been done.

Fig. 8.

Showing the groove from initial drilling to take the canal wall down partially.

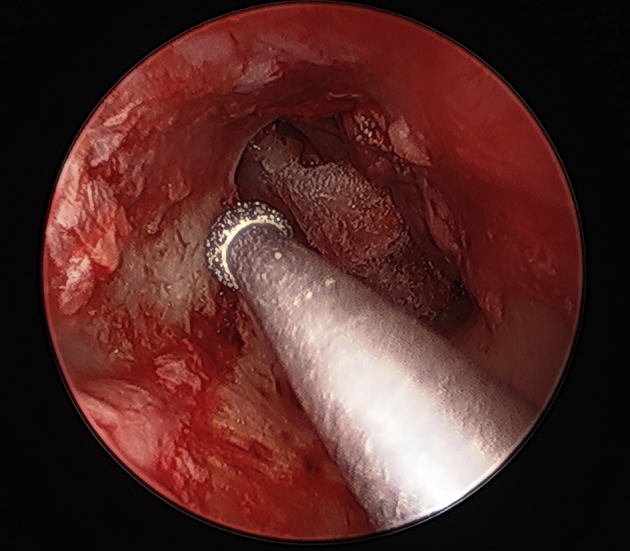

Fig. 9.

Drilling the canal wall to gain access into the mastoid antrum, 2 mm drill bit.

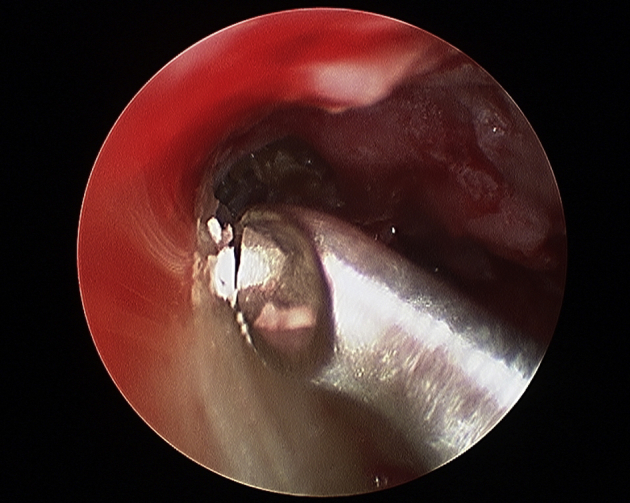

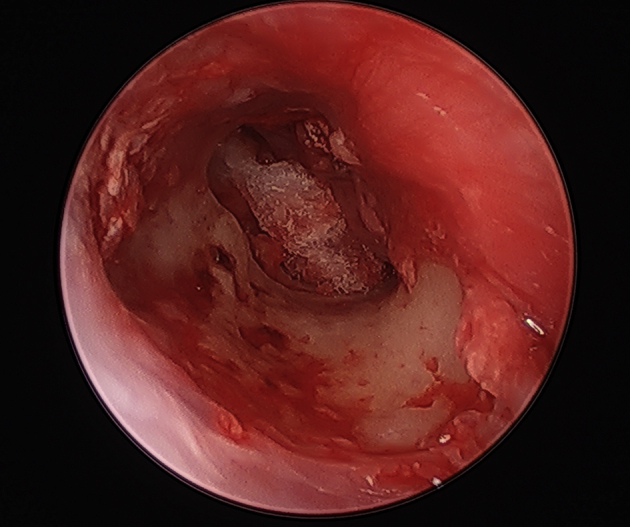

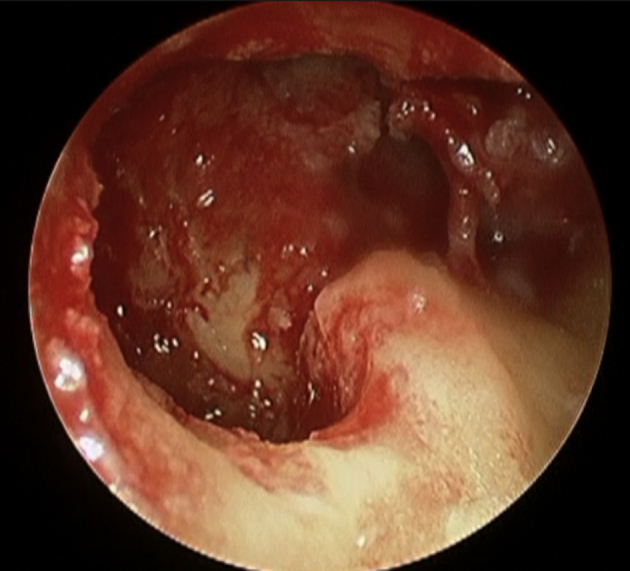

Fig. 10.

Wide exposure of the antrum, attic and cog after initial canal wall drilling.

Fig. 11.

Partial canal wall down drilled with full exposure of mastoid and lateral semicircular canal, Fallopian canal, cochlearoforma process and chorda tympani nerve.

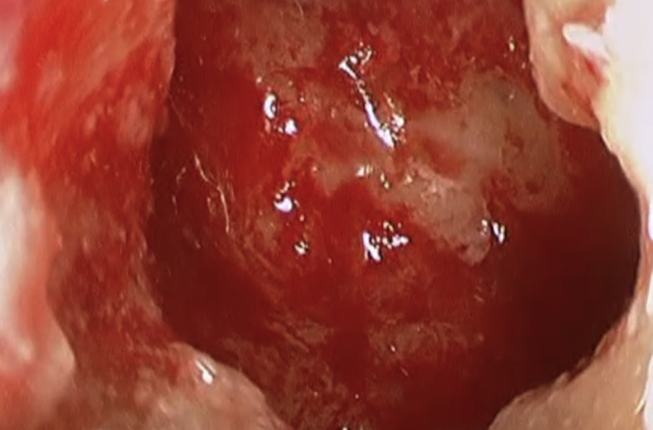

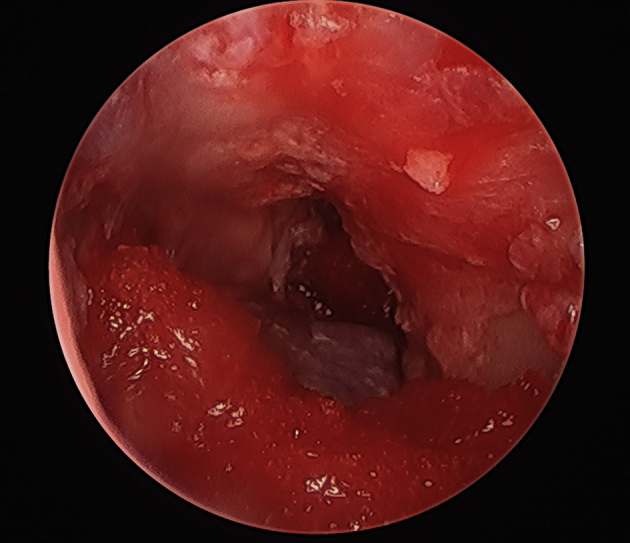

Fig. 12.

Mastoid antrum widely exposed and cholesteatoma resected.

Fig. 13.

Mastoid cavity viewed via a 70 degree rigid scope used transcanal.

Fig. 14.

Cartilage reconstruction of partial canal wall defect showing raised tympanomeatal flap.

Fig. 15.

Cartilage reconstruction of canal wall defect and attic defect.

Fig. 16.

Tympanomeatal flap put back in place with cartilage repair underneath the flap.

Fig. 17.

Ear can repaired and sealed with gelfoam soaked with Tissue Glue, no sponge packing.

Results

A total of four endoscopic transcanal modified canal-wall-down mastoidectomy (ETM-CWD) cases have been performed in four adult patients over a three-year period, 2014–2016. These were all primary cases without prior ear surgery. All patients are still being followed.

There have been no major complications. Specifically, there were no middle fossa tegmen violation, no cerebrospinal fluid leak, no facial nerve injury, no inner ear injury and no postoperative worsening of bone conduction thresholds. Chorda tympani nerve was preserved in all cases. In all cases, cholesteatoma had engulfed the incus. Malleus head and incus had to be removed. Stapes was preserved in three cases. In one case, Stapes supra-structure was eroded by Cholesteatoma, leaving the stapes footplate intact. Medial eardrum grafting using temporalis fascia and conchal cartilage repair of the bony defects were performed in all cases.

The first case performed in the series, developed postoperative meatal narrowing due to poor healing of the posterior meatal skin. The shaft of the drill had caused some friction burn to the meatal skin which failed to heal properly. After this experience, all subsequent cases had meatal skin retracted out of the way with fishhook skin retractors, and this issue has not happened anymore. The patient with meatal stenosis underwent an endoscopic meatoplasty, along with endoscopic second-look mastoid and middle ear exploration one-year after the primary ETM-CWD procedure. No cholesteatoma was detected, and a total ossicular reconstruction prosthesis (TORP) was successfully placed to reconstruct the ossicular chain. The patient has been doing well two years after the second-look surgery, with an air-bone gap closed to 20 dB, with a self-cleaning intact ear canal with no issues.

The other three patients have been enrolled in the serial diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) propeller magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) protocol. So far, at one and two year follow-ups, all three cases have had negative MRI. The MRI cholesteatoma protocol requires the first postop DWI MRI to be done at one year, and if it proves to be negative for cholesteatoma, then a second DWI MRI is done two years postop. If the second MRI remains unequivocally negative, then the patient is followed clinically once a year for 10 years. Any suspicious findings on the second DWI MRI triggers an endoscopic second-look procedure.

Discussion

Endoscopic transcanal modified canal-wall-down mastoidectomy (ETM-CWD) for resection of antral cholesteatoma in sclerotic small mastoids is feasible and seems to be safe. The surgical technique requires advanced endoscopic skills and attention to detail in small areas. Postoperative pain seems to be negligible and recovery is fast with no mastoid dressing, and no external incisions or sutures.

Since this technique is in essence a “closed cavity” approach, the rules of cholesteatoma resection and surveillance applied to the closed cavity approaches should apply here as well. This means that all ETM-CWD patients will either undergo an endoscopic second-look procedure in 8–10 months, or enroll in the special DWI Propeller MRI cholesteatoma surveillance protocol, with and without contrast. Such serial MRI are done in one year and two years postoperatively.

Second-look surgery is performed transcanal and endoscopically. Care must be exercised to elevate the attic cartilage attached to the tympanomeatal flap in one piece, but leaving the canal wall cartilage in place. Once the middle ear is explored, decision could be made to proceed with any ossicular chain reconstruction as needed or not.

After the middle ear is explored, the canal wall cartilage is gently lifted up and the small mastoid cavity is examined for cholesteatoma. Second-look procedures can often be performed under local anesthesia with intravenous sedation and since most cases are negative, general anesthesia thus may be avoided in the majority of patients.

Conclusions

Tarabichi11 showed in 2000 that endoscopic management of cholesteatoma is minimally invasive and has comparable results to traditional postauricular methods. The ETM-CWD technique presented here is an evolution of standard endoscopic ear surgery utilizing an old inside-out method with far more advanced instrumentation and greater exposure and field of view.

The “inside-out” attico-antrotomy has been around for decades and has been traditionally performed through either endaural or postauricular incisions. Its safety in competent hands has been established and this has been a great surgical technique for decades. This paper has a very small sample size and shows the potential feasibility, safety and success of this new twist to an old surgical technique. A larger sample size is needed to establish long-term results as compared with conventional canal-wall-down mastoidectomy with or without mastoid obliteration. Further clinical cases with longer follow-ups are needed.

The Transcanal Endoscopic Ear surgery experience now empowers the otologist to perform this well-established surgical technique under superior vision, achieving excellent exposure while using instruments designed for endoscopic ear surgery. This approach, in well-trained and experienced hands, allows complete resection of cholesteatoma and full reconstruction of the bony ear canal, thus providing the best of both worlds, specifically the unencumbered view of the disease as seen in the canal-wall-down approach, and the normal physiologic status of canal-wall-up without a cavity that needs long-term maintenance.

Otologic surgeons wishing to proceed with this approach should accrue substantial experience using rigid endoscopes in far less complicated ear cases before undertaking this rather advanced endoscopic technique. This approach, in early cases, can prove to be difficult and frustrating. However, once it is mastered, it will be rewarding for both the patients and the surgeons.

Edited by Yu-Xin Fang

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Medical Association.

References

- 1.Tarabichi M. Endoscopic management of limited attic cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(7):1157–1162. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200407000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nikolopoulos T.P., Gerbesiotis P. Surgical management of cholesteatoma: the two main options and the third way–atticotomy/limited mastoidectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1222–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheehy J.L., Patterson M.E. Intact canal wall tympanoplasty with mastoidectomy. A review of eight years' experience. Laryngoscope. 1967;77:1502–1542. doi: 10.1288/00005537-196708000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheehy J.L., Brackmann D.E., Graham M.D. Cholesteatoma surgery: residual and recurrent disease. A review of 1,024 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1977;86:451–462. doi: 10.1177/000348947708600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naguib M.B., Aristegui M., Saleh E., Cokkeser Y., Russo A., Sanna M. Surgical management of epitympanic cholesteatoma with intact ossicular chain: the modified Bondy technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1994;111:545–549. doi: 10.1177/019459989411100501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheehy J.L. The intact canal wall technique in management of aural cholesteatoma. J Laryngol Otol. 1970;84:1–31. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100071590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tos M. Modification of combined-approach tympanoplasty in attic cholesteatoma. Arch Otolaryngol. 1982;108(12):772–778. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1982.00790600016005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lempert J. Lempert endaural subcortical mastoidotympanectomy for the cure of chronic persistent suppurative otitis media. Arch Otolaryngol. 1949;49(1):20–35. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1949.03760070027003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong Q., Deng X., Wang X., Zhang Y. The application of spiral CT in diagnosing otitis media with cholesteatoma. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2007;21(1):22–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaurano J.L., Joharjy I.A. Middle ear cholesteatoma: characteristic CT findings in 64 patients. Ann Saudi Med. 2004;24(6):442–447. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2004.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarabichi M. Endoscopic management of cholesteatoma: long term results. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(6):874–881. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59980070017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]