Abstract

Patient: Male, 90

Final Diagnosis: Ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm

Symptoms: Epigastric pain • Fever

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: Open cholecystectomy

Specialty: Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm is rare, and some cases are associated with inflammation of the gallbladder. There is limited information regarding this condition, and the clinical features remain unclear. This report is a case of ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) imaging and treated with urgent cholecystectomy and is supported by a literature review of previous cases.

Case Report:

A 90-year-old man, who had developed acute cholecystitis due to a gallstone one month previously, was referred to our hospital. He developed fever and epigastric pain while waiting for a scheduled elective cholecystectomy. Laboratory investigations showed elevated markers of inflammation and elevated hepatobiliary enzyme levels. Computed tomography (CT) imaging showed cholecystitis and pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery. The pseudo-aneurysm had ruptured and was accompanied by the formation of a hematoma within the gallbladder that involved the liver bed. Having made the preoperative diagnosis, an urgent open laparotomy was performed, during which the gallbladder was found to have perforated. The hematoma penetrated into the liver bed. Cholecystectomy was performed, and the pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery was extirpated. There were no serious postoperative complications. A literature review identified 50 previously reported case of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm.

Conclusions:

A case of ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm, successfully treated with urgent cholecystectomy is reported, supported by a literature review of previous cases and characterization of the clinical features of this rare condition.

MeSH Keywords: Aneurysm, False; Aneurysm, Ruptured; Cholecystitis; Gallbladder Diseases

Background

Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm is rare, and some cases are associated with inflammatory processes in the gallbladder. Although the pathogenesis of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm remains unclear, it is likely that the artery is eroded by inflammation of the arterial wall, resulting in damage to the adventitia, with localized weakness in the vessel wall and formation of a pseudoaneurysm [1].

Acute or chronic cholecystitis associated with cholelithiasis are common diseases of the gallbladder. The relationship between inflammation of the gallbladder and cystic artery pseudoaneurysm might suggest that the latter occurs more frequently. However, although the incidence of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm is unclear, it is a rare condition when compared with the common incidence of cholecystitis. Therefore, studies into the etiology and pathogenesis of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm have been limited. Although cases of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm can be associated with surgical procedures that involve the biliary tract, including cholecystectomy, the mechanism of the formation of arterial pseudoaneurysm is likely to be traumatic, and different from cystic artery pseudoaneurysm associated with cholecystitis.

From a review of the published literature, there have been only 50 previously reported cases of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm associated with cholecystitis. There is limited information regarding this condition, and the clinical features remain unclear. Further studies of cases of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm associated with cholecystitis are needed to characterize the condition and evaluate the optimum management.

This report is of a case of ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) imaging and treated with urgent cholecystectomy and is supported by a literature review of previous cases.

Case Report

One month before hospital admission, a 90-year-old man developed acute cholecystitis associated with a gallstone and was referred to our hospital for planned elective cholecystectomy. His past medical history included prior myocardial infarction and sick sinus syndrome. He had a cardiac pacemaker and was prescribed antithrombotic drugs (aspirin 100 mg/day, and clopidogrel 75 mg/day) and was categorized as New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class II [2]. Computed tomography (CT) imaging showed a gallstone measuring 29 mm in diameter within the gallbladder. An elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy was scheduled, and the antithrombotic drugs were replaced by unfractionated heparin during the perioperative period, with the intention of resuming his routine antithrombotic drug medication following hospital discharge.

Twelve days before his scheduled hospitalization, he suddenly developed fever and epigastric pain while waiting for surgery. On admission to hospital, physical examination showed that his temperature was 38.8°C, his blood pressure was 101/61 mmHg, and his heart rate was 90 bpm with epigastric and right upper quadrant tenderness on abdominal palpation.

Laboratory investigations showed increased leukocytes at 20,700/μL (normal range, 3,500–8,500/μL) and C-reactive protein (CRP) of 3.33 mg/dL (normal range, <0.3 mg/dL). Hepatobiliary enzymes were elevated as follows: aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 1,413 U/L (normal range, 10–37 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 883 U/L (normal range 4–40 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 1392 U/L (normal range, 98–328 U/L), γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) 313 U/L (normal range, 11–64 U/L), total bilirubin 2.05 mg/dL (normal range, 0.2–1.2 mg/dL), direct (conjugated) bilirubin 1.19 mg/dL (normal range, 0–0.3 mg/dL).

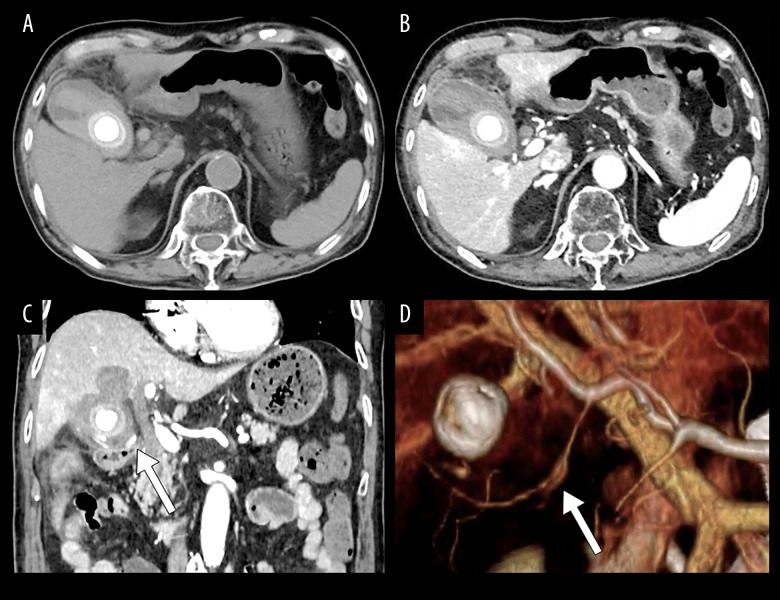

Imaging was performed using computed tomography (CT), which showed an area of high density within the gallbladder and common bile duct, suggesting intraluminal bleeding and hematoma (Figure 1A). Inflammation of the fat (fat necrosis) surrounding the gallbladder was present on imaging, in keeping with acute cholecystitis. Contrast-enhanced CT imaging also showed that there was spread of the hematoma into the liver bed (Figure 1B, 1C.). There was an 8 mm diameter nodular lesion associated with the cystic artery, which showed the same degree of contrast-enhancement as the aorta (Figure 1C), which had not been seen in the previous CT, one month previously. The lesion was confirmed to be associated with the cystic artery by three-dimensional CT angiography (Figure 1D), and was diagnosed as a ruptured pseudoaneurysm.

Figure 1.

Preoperative computed tomography (CT) findings. (A) A gallstone measuring 29 mm in diameter is present in the gallbladder. The lumen of the gallbladder and the common bile duct (CBD) are shown as high-density areas. (B, C) Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) images show extensive inflammation of the fat (fat necrosis) surrounding the gallbladder and the area of spread of the hematoma into the liver bed (B axial scan; C coronal scan), An 8mm nodular lesion is also shown on the cystic artery. (D) Three-dimensional (3-D) CT angiography confirmed the nodular lesion.

Even with acute cholecystitis and ruptured pseudoaneurysm accompanying hemobilia and spread of the hematoma into the liver bed, the patient was hemodynamically stable. However, because of the potential risk of severe infection associated with cholecystitis and the possibility of hemorrhagic shock due to bleeding, an urgent open cholecystectomy was planned. At the time, he was classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status (ASAPS) Class 3E [3].

During surgical laparotomy, the gallbladder was inflamed, perforated, and was found to be adherent to the surrounding tissue. Following dissection of the adhesions, the hematoma was found to involve the liver bed. The gallbladder was opened, and the lumen of the gallbladder contained hemorrhage and hematoma, and there was spread of the hematoma into the liver bed (Figure 2). There was no intraperitoneal bleeding. Following identification of the cystic artery and cystic duct, both were ligated. Cholecystectomy was performed, and the pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery was extirpated. The operation time was 134 minutes, and the intraoperative blood loss was 540 ml. Histopathological examination of the resected gallbladder specimen showed acute on chronic cholecystitis. The patient had no serious postoperative complications, but required postoperative rehabilitation to regain mobility, and was transferred to a rehabilitation hospital on the fourth postoperative day.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative appearance of the gallbladder at laparotomy. At laparotomy, the lumen of the gallbladder, and the penetrated space in the liver bed were filled with blood (arrow: lumen of the gallbladder).

Discussion

A rare case of ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm, successfully treated with urgent cholecystectomy, has been reported. The development of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm is associated with gallbladder inflammation. Review of the literature does not provide details of the exact incidence of this association, but from the low number of previously published cases reports, the incidence is low when compared with the frequency of cholecystitis.

It has been hypothesized that cystic artery pseudoaneurysm is masked by the inflammation associated with cholecystitis that promotes the formation of both the pseudoaneurysm and the hematoma formation [4]. However, the clinical features of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm have not been comprehensively investigated because of the low incidence. We report a recent case in the hopes of better characterizing this rare disease.

A literature search of the Medline database, up to April 2017, for cases of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm, extracted cases in which the term ‘cystic artery pseudoaneurysm’ was given as the diagnosis. In the literature review, cases in which cystic artery pseudoaneurysm developed following surgical procedures, such as cholecystectomy, were excluded because the formation of the pseudoaneurysm in these cases may be related to the surgery itself [5]. As a result, to the best of our knowledge, 50 cases of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm have been previously published [1,4,6–49]. The clinical features of the previously published 50 cases, and the current case, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Reported cases of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm.

| No. | Authors | Year | Age | Sex | Size (mm) | Cholecystitis | Gallstone | Rupture | Intraperitoneal bleeding | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hakami et al. [6] | 1976 | 56 | M | NA | + | + | + | − | OC |

| 2 | Reddy et al. [7] | 1983 | 61 | M | 30 | + | + | + | − | OC |

| 3 | Rhee et al. [8] | 1987 | 73 | M | NA | + | + | + | + | OC |

| 4 | Wu et al. [9] | 1988 | 64 | M | 30 | + | + | + | + | OC |

| 5 | Strickland et al. [10] | 1991 | 72 | F | NA | + | + | + | − | OC |

| 6 | Read et al. [11] | 1991 | 71 | F | 10 | + | + | + | − | OC |

| 7 | Barba et al. [12] | 1994 | 70 | M | 20 | + | + | + | − | TAE + OC |

| 8 | Nakajima et al. [13] | 1996 | 72 | M | 30 | + | + | + | − | OC |

| 9 | England et al. [14] | 1998 | 71 | F | NA | + | + | + | − | TAE + OC |

| 10 | Kaman et al. [15] | 1998 | 32 | F | 10 | + | + | + | − | OC |

| 11 | Maeda et al. [16] | 2002 | 62 | M | NA | + | + | + | − | TAE + OC |

| 12 | Gutiérrez et al. [17] | 2004 | 66 | F | NA | + | + | + | − | TAE + OC |

| 13 | Morioka et al. [18] | 2004 | 43 | M | NA | + | + | + | − | OC |

| 14 | Joyce et al. [19] | 2006 | 58 | M | 2 | + | − | + | − | OC |

| 15 | Sibulesky et al. [20] | 2006 | 72 | M | NA | NA | − | + | − | OC |

| 16 | Lee et al. [21] | 2006 | 72 | F | NA | + | + | + | − | TAE + OC |

| 17 | Pérez-Castri et al. [22] | 2006 | 77 | F | NA | + | NA | + | − | TAE |

| 18 | Saluja et al. [23] | 2007 | 43 | F | 30 | + | + | + | − | OC |

| 19 | Akatsu et al. [1] | 2007 | 58 | M | 20 | + | + | + | − | OC |

| 20 | Ghoz et al. [24] | 2007 | 63 | M | NA | + | − | + | + | TAE + OC |

| 21 | Shimada et al. [25] | 2008 | 68 | M | NA | + | NA | + | − | TAE + OC |

| 22 | Machida et al. [26] | 2008 | 71 | M | 10 | + | + | − | − | OC |

| 23 | Sousa et al. [27] | 2009 | 84 | M | 14 | + | + | + | − | OC |

| 24 | Mullen et al. [28] | 2009 | 82 | M | NA | + | + | − | − | TAE |

| 25 | Mullen et al. [28] | 2009 | 75 | F | 21 | + | + | + | − | TAE |

| 26 | Desai et al. [4] | 2010 | 78 | F | 25 | + | + | + | − | TAE |

| 27 | Nkwam et al. [29] | 2010 | 71 | M | 30 | + | + | − | − | TAE + LC |

| 28 | Leung et al. [30] | 2010 | 82 | M | NA | NA | NA | + | − | TAE |

| 29 | Hague et al. [31] | 2010 | 83 | M | NA | NA | NA | + | + | TAE |

| 30 | Hague et al. [31] | 2010 | 79 | M | NA | + | + | + | − | TAE |

| 31 | Hague et al. [31] | 2010 | 83 | M | NA | NA | NA | NA | + | TAE |

| 32 | Ahmed et al. [32] | 2010 | 54 | M | 20 | + | + | + | + | TAE + OC |

| 33 | Anand et al. [33] | 2011 | 35 | M | 21 | + | − | + | − | OC |

| 34 | Siddiqui et al. [34] | 2011 | 58 | M | NA | + | + | + | + | TAE + OC |

| 35 | Chong et al. [35] | 2012 | 56 | M | 20 | NA | NA | + | − | TAE + OC |

| 36 | Dewachter et al. [36] | 2012 | 74 | F | 20 | + | + | − | − | LC |

| 37 | Mokrane et al. [37] | 2013 | 67 | M | NA | + | NA | + | − | TAE |

| 38 | Fung et al. [38] | 2013 | 64 | M | NA | + | + | + | + | OC |

| 39 | Nana et al. [39] | 2013 | 79 | F | 25 | + | + | + | − | TAE |

| 40 | Nana et al. [39] | 2013 | 74 | M | NA | + | + | + | − | TAE + LC |

| 41 | Liang et al. [40] | 2013 | 88 | F | NA | + | + | + | + | OC |

| 42 | Suzuki et al. [41] | 2013 | 85 | F | 10 | + | + | − | − | OC |

| 43 | Glaysher et al. [42] | 2014 | 86 | M | 20 | + | + | + | − | OC |

| 44 | Kulkarni et al. [43] | 2014 | 55 | M | NA | + | + | + | − | TAE + OC |

| 45 | She et al. [44] | 2015 | 64 | M | NA | + | + | + | − | TAE + OC |

| 46 | Shelmerdine et al. [45] | 2015 | 72 | M | 6 | + | + | + | − | TAE |

| 47 | Muñoz-Villafranca et al. [46] | 2015 | 74 | M | 18 | + | + | + | − | TAE |

| 48 | Loizides et al. [47] | 2015 | 61 | F | 15 | + | + | − | − | LC |

| 49 | Alis et al. [48] | 2016 | 36 | M | NA | + | + | − | − | LC |

| 50 | Lozano-Cruz et al. [49] | 2017 | 85 | F | NA | + | + | + | − | TAE |

| 51 | Our case | 2017 | 90 | M | 8 | + | + | + | − | OC |

| Summary of the 51 cases | 68±14 | M; 69% (35/51) F; 31% (16/51) |

19±8 | +: 100% (46/46) −; 0% (0/46) |

+: 91% (40/44) −; 9% (4/44) |

+: 86% (43/50) −; 14% (7/50) |

+: 18% (9/51) −; 82% (42/51) |

OC: 87% (33/38) LC; 13% (5/38) |

Data are summarized below and some data in the summary are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. M – male; F – female; LC – laparoscopic cholecystectomy; OC – open cholecystectomy; TAE – transcatheter arterial embolization; NA – not assigned.

When compared with the identified previous 50 cases, the case of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm that we report was unique in several ways. This case was unique in that the age of the patient was the oldest case of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm ever reported, as the patient was 90 years old; the age range of the previously published cases was 32–90 years, with a median age at diagnosis of 68 years. Also, in this reported case, the spread of the hematoma into the liver bed without intraperitoneal bleeding was rarely reported in previous cases. Even with acute cholecystitis and ruptured pseudoaneurysm accompanying hemobilia and spread of the hematoma, this patient was hemodynamically stable. However, he had a potential risk of severe infection and hemorrhagic shock due to the bleeding. Therefore, due to the potential life-threatening clinical status of the patient in this report, curative surgery was considered to be urgently required. A shorter operation time was given priority when choosing a surgical procedure because of the potential for hemodynamic destabilization. Therefore, open cholecystectomy was chosen instead of laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

However, because techniques and devices for laparoscopic surgery continue to develop, in the recent literature, laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been indicated for the surgical management of previous cases of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm when the patients were clinically stable. Review of the literature has confirmed that cystic artery pseudoaneurysm formation is associated with inflammation of the gallbladder, and ruptured cases are more common than unruptured cases. Our case indicates that ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm can lead to spread of the hematoma into the liver bed. A literature review of the relationship between pseudoaneurysm formation and antithrombotic drugs has shown that there have been few reports of this association.

Conclusions

A case of ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm, successfully treated with urgent cholecystectomy is reported, supported by a literature review of previous cases and characterization of the clinical features of this rare condition. This case report contributes to the better characterization of the clinical features of this rare and poorly understood condition.

Acknowledgments

None

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Akatsu T, Tanabe M, Shimizu T, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery secondary to cholecystitis as a cause of hemobilia: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37:412–17. doi: 10.1007/s00595-006-3423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128(16):e240–327. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829e8776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dripps RD, Lamont A, Eckenhoff JE. The role of anesthesia in surgical mortality. JAMA. 1961;178:261–66. doi: 10.1001/jama.1961.03040420001001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Desai AU, Saunders MP, Anderson HJ, Howlett DC. Successful transcatheter arterial embolisation of a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to calculus cholecystitis: A case report. J Radiol Case Rep. 2010;4:18–22. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v4i2.268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Molla Neto OL, Ribeiro MA, Saad WA. Pseudoaneurysm of cystic artery after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2006;8:318–19. doi: 10.1080/13651820600869628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hakami M, Beheshti G, Amirkhan A. Hemobilia caused by rupture of cystic artery aneurysm. Am J Proctol. 1976;27:56–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reddy SC. Pseudoaneurysm of cystic artery with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. South Med J. 1983;76:85–86. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198301000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rhee JW, Bonnheim DC, Upson J. Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. NY State J Med. 1987;87:47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu TC, Liu TJ, Ho YJ. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Case report. Acta Chir Scand. 1988;154:151–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strickland SK, Khoury MB, Kiproff PM, Raves JJ. Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm: A rare cause of hemobilia. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1991;14:183–84. doi: 10.1007/BF02577726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Read A, Lannan M, Chou ST, Hennessy O. Bleeding cystic artery aneurysm: Rare cause of haemobilia. Aust NZJ Surg. 1991;61:159–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1991.tb00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barba CA, Bret PM, Hinchey EJ. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery: A rare cause of hemobilia. Can J Surg. 1994;37:64–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakajima M, Hoshino H, Hayashi E, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:750–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02347630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.England RE, Marsh PJ, Ashleigh R, Martin DF. Case report: Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery: A rare cause of haemobilia. Clin Radiol. 1998;53:72–75. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(98)80041-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaman L, Kumar S, Behera A, Katariya RN. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery: A rare cause of hemobilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1535–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.475_y.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maeda A, Kunou T, Saeki S, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with hemobilia treated by arterial embolization and elective cholecystectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:755–58. doi: 10.1007/s005340200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gutiérrez G, Ramia JM, Villar J, et al. Cystic artery pseudoaneurism from an evolved acute calculous cholecystitis. Am J Surg. 2004;187:519–20. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2003.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morioka D, Ueda M, Baba N, et al. Hemobilia caused by pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19:724–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03461.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joyce MR, Donnolly M, O’Shea L, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery: A diagnostic dilemma and rare cause of haemobilia. Ir J Med Sci. 2006;175:81. doi: 10.1007/BF03169011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sibulesky L, Ridlen M, Pricolo VE. Hemobilia due to cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. Am J Surg. 2006;191:797–98. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2005.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee JW, Kim MY, Kim YJ, Suh CH. CT of acute lower GI bleeding in chronic cholecystitis: Concomitant pseudoaneurysm of cystic artery and cholecystocolonic fistula. Clin Radiol. 2006;61:634–36. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pérez-Castrillón JL, Mendo M, Calero H. Hemorrhage into the gallbladder caused by pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery. Endoscopy. 2006;38(Suppl. 2):E50. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saluja SS, Ray S, Gulati MS, et al. Acute cholecystitis with massive upper gastrointestinal bleed: A case report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:12. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ghoz A, Kheir E, Kotru A, et al. Hemoperitoneum secondary to rupture of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2007;6:321–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimada K, Sakamoto Y, Esaki M, Kosuge T. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery associated with xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Dig Surg. 2008;25:8–9. doi: 10.1159/000114194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Machida H, Ueno E, Shiozawa S, et al. Unruptured pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery with acute calculous cholecystitis incidentally detected by computed tomography. Radiat Med. 2008;26:384–87. doi: 10.1007/s11604-008-0243-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sousa HT, Amaro P, Brito J, et al. Hemobilia due to pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2009;33:80–82. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mullen R, Suttie SA, Bhat R, et al. Microcoil embolisation of mycotic cystic artery pseudoaneurysm: A viable option in high-risk patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2009;32:1275–79. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9590-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nkwam N, Heppenstall K. Unruptured Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery associated with acute calculus cholecystitis. J Surg Case Rep. 2010;2010:4. doi: 10.1093/jscr/2010.2.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leung JL, Kan WK, Cheng SC. Mycotic cystic artery pseudoaneurysm successfully treated with transcatheter arterial embolisation. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16:156–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hague J, Brennand D, Raja J, Amin Z. Cystic artery pseudoaneurysms in hemorrhagic acute cholecystitis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 33:1287–90. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-9861-7. 201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed I, Tanveer UH, Sajjad Z, et al. Cystic artery pseudo-aneurysm: A complication of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Br J Radiol. 2010;83:e165–67. doi: 10.1259/bjr/34623636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anand U, Thakur SK, Kumar S, et al. Idiopathic cystic artery aneurysm complicated with hemobilia. Ann Gastroenterol. 2011;24:134–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siddiqui NA, Chawla T, Nadeem M. Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to acute cholecystitis as cause of haemobilia. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1136/bcr.07.2011.4480. pii: bcr0720114480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chong JJ, O’Connell T, Munk PL, et al. Case of the month #176: Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2012;63:153–55. doi: 10.1016/j.carj.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dewachter L, Dewaele T, Rosseel F, et al. Acute cholecystitis with pseudo-aneurysm of the cystic artery. JBR-BTR. 2012;95:136–37. doi: 10.5334/jbr-btr.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mokrane FZ, Alba CG, Lebbadi M, et al. Pseudoaneurism of the cystic artery treated with hyperselective embolisation alone. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2013;94:641–43. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fung AK, Vosough A, Olson S, et al. An unusual cause of acute internal haemorrhage: Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to acute cholecystitis. Scott Med J. 2013;58:e23–26. doi: 10.1177/0036933013482667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nana GR, Gibson M, Speirs A, Ramus JR. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding: A rare complication of acute cholecystitis. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2013;4:761–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liang X, Lü JM, Meng N, Jin RA, Cai XJ. Hemorrhagic shock caused by rupture of cystic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to calculous cholecystitis. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:4590–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Suzuki S, Saito Y, Nakamura K, et al. Unruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm accompanied by Mirizzi syndrome: A report of a case. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2013;6:490–95. doi: 10.1007/s12328-013-0434-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glaysher MA, Cruttenden-Wood D, Szentpali K. A rare cause of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage: Ruptured cystic artery pseudoaneurysm with concurrent cholecystojejunal fistula. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kulkarni V, Deshmukh H, Gupta R. Pseudoaneurysm of anomalous cystic artery due to calculous cholecystitis. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-207069. pii: bcr2014207069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.She WH, Tsang S, Poon R, Cheung TT. Gastrointestinal bleeding of obscured origin due to cystic artery pseudoaneurysm. Asian J Surg. 2017;40(4):320–23. doi: 10.1016/j.asjsur.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shelmerdine SC, Ameli-Renani S, Lynch JO, Gonsalves M. Transarterial catheter embolisation for an unusual cause of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-206837. pii: bcr2014206837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muñoz-Villafranca C, García-Kamirruaga Í, Góme-García P, et al. Pseudoaneurysm of the cystic artery: An uncommon cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a case of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2015;107:375–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loizides S, Ali A, Newton R, Singh KK. Laparoscopic management of a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm in a patient with calculus cholecystitis. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;14:182–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Alis D, Ferahman S, Demiryas S, et al. Laparoscopic management of a very rare case: Cystic artery pseudoaneurysm secondary to acute cholecystitis. Case Rep Surg. 2016;2016:1489013. doi: 10.1155/2016/1489013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lozano-Cruz P, Arenas P, Moral I. Hemobilia related to cystic artery pseudoaneurysm as a cause of acute pancreatitis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2017;109:316. doi: 10.17235/reed.2017.4532/2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]