Abstract

Objective

With an elderly population that is set to more than double by 2050 worldwide, there will be an increased demand for elderly care. This poses several impediments in the delivery of high-quality health and social care. Socially assistive robot (SAR) technology could assume new roles in health and social care to meet this higher demand. This review qualitatively examines the literature on the use of SAR in elderly care and aims to establish the roles this technology may play in the future.

Design

Scoping review.

Data sources

Search of CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, MEDLINE, PsychINFO and Scopus databases was conducted, complemented with a free search using Google Scholar and reference harvesting. All publications went through a selection process, which involved sequentially reviewing the title, abstract and full text of the publication. No limitations regarding date of publication were imposed, and only English publications were taken into account. The main search was conducted in March 2016, and the latest search was conducted in September 2017.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria consist of elderly participants, any elderly healthcare facility, humanoid and pet robots and all social interaction types with the robot. Exclusions were acceptability studies, technical reports of robots and publications surrounding physically or surgically assistive robots.

Results

In total, 61 final publications were included in the review, describing 33 studies and including 1574 participants and 11 robots. 28 of the 33 papers report positive findings. Five roles of SAR were identified: affective therapy, cognitive training, social facilitator, companionship and physiological therapy.

Conclusions

Although many positive outcomes were reported, a large proportion of the studies have methodological issues, which limit the utility of the results. Nonetheless, the reported value of SAR in elderly care does warrant further investigation. Future studies should endeavour to validate the roles demonstrated in this review.

Systematic review registration

NIHR 58672.

Keywords: socially assistive robots, elderly, robots, geriatric medicine, social medicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first scoping review of the literature that has evaluated and categorised the effects of socially assistive robot (SAR) interventions aimed to improve the health and social care of elderly people.

The novelty of the field means that the quantity and quality of studies available in the current literature is limited, making generalisations difficult.

The retrospective creation of SAR roles grouped together sets of studies that differed in quality, design and sometimes outcome, which may mislead the actual weight of data in the respective roles.

Introduction

The global population is undergoing a demographic shift. Life expectancy is growing, and the postwar baby boom generation is entering retirement. The implications on resource allocation will impact the delivery of elderly care. As of 2015,1 21% of Western Europe’s population were over the age of 60 years, and this is expected to rise to 33% by 2030. By 2050, there are expected to be more people over the age of 60 years globally than under 15 years, reaching a total population of 2.1 billion compared with 901 million in 2015. This is compounded by a proportional decrease in the number of social and healthcare providers shouldering this increased burden. In 2015, seven workers were allocated for every elderly person globally, but this is projected to fall to 4.9 in 15 years.1 Moreover, the situation is magnified in Europe by an accelerated ageing population. Currently, there are 3.5 workers for every elderly person, but this is set to fall to 2.4 by 2030. The shift in societal proportions will place new pressures on all aspects of elderly care.

Loneliness, for instance, is a consequence of social, psychological and personal factors. Over half of people over the age of 75 live alone2 and 17% of older people see family, friends or neighbours less than once a week.3 A recent meta-analysis4 showed that the impact of loneliness and isolation carries the same mortality risk as smoking 15 cigarettes a day. This is compounded by the fact that social care is a labour intensive industry in a world with a proportionally shrinking workforce.

Throughout many industries, the ‘robot revolution’ promises to solve this growing personnel shortage. At present, physically or surgically assistive robots dominate the healthcare sector’s robot usage. This includes: (1) increasingly sophisticated wheelchairs transforming the limitations imposed on paraplegics; (2) robotic limbs redefining amputee capabilities; and (3) robotic surgeons revolutionising how and where surgery can be performed. Nonetheless, physically assistive robots do not combat the increasing mental health burden recognised in the elderly population. It is here that the concept of socially assistive robots (SARs) is gaining headway. These are robots adept at completing a complex series of physical tasks with the addition of a social interface capable of convincing a user that the robot is a social interaction partner.5

SARs have been categorised into two operational groups: (1) service robots and (2) companion robots. Service robots are tasked with aiding activities of daily living.6 Companion robots, by contrast, are more generally associated with improving the psychological status and overall well-being of its users. Such examples include Sony’s AIBO7 and Paro.8 Despite much of the hype, the utilisation of this technology in elderly care is not completely ascertained.

The aim of this scoping review is to establish the clinical usefulness of SARs in elderly care. Through examination and qualitative analyses of existing literature, studies will showcase the utility of SAR and their associated clinical outcomes. A better understanding of SAR and its ability to provide integral care, both socially and physiologically, will provide an indication of its future role in society.

Methodology

The protocol for this review was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.9

Search strategy

The following bibliographical databases were searched: CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Embase, MEDLINE, PsychINFO and Scopus using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH or where appropriate, the database specific thesaurus equivalent) or text word terms. The database search query was composed of two search concepts: the intervention (SAR) and the context (elderly care). Free-text terms for the intervention included: ‘service robot*’, ‘therapeutic robot*’ and ‘socially assistive robot*’; their associated MeSH terms were ‘Robotics’ and ‘Artificial Intelligence’. The names of specific robot systems were also searched for. The free words used for the context included: ‘elder*’, ‘senior*’, ‘older person*’, ‘old people’ and ‘dementia’; their associated MeSH term was ‘Aged, 80 and over’. The use of the asterisk (*) enables the word to be treated as a prefix. For example, ‘elder*’ will represent ‘elderly’ and ‘eldercare’ among others (see online supplementary material for an example of a bibliographical search). Additional studies were selected through a free search (Google Scholar) and from reference lists of selected publications and relevant reviews. The main search was conducted in March 2016, and the latest search was conducted in September 2017.

bmjopen-2017-018815supp001.pdf (185.9KB, pdf)

Study selection

Two reviewers (JA and AA-H) independently screened the publications in a three-step assessment process: the title, abstract and full text and selection were made in accordance with inclusion criteria. All publications collected during the database search, free search and reference list harvesting were scored on a three-point scale (0=not relevant, 1=possibly relevant and 2=very relevant), and those with a combined score of 2 between the reviews would make it through to the next round of scoring. All publications with a total score of 0 were excluded. A publication with a combined score of 1 indicated a disagreement between the reviewers and would be resolved through discussion. At the end of the full-text screening round, a final set of publications to be included into the review was acquired. Cohen’s kappa coefficient was calculated to ascertain the agreement between the reviewers in the title, abstract and full-text screening phases.

A study was considered eligible if it assessed the usefulness of SAR in the elderly population with a clinical outcome measure. A study that simply assessed the robot’s acceptability to elderly users without a clinical outcome measure, or was a technical report, or concerned the use of physically or surgically assistive robots was excluded. No limitations regarding date of publication were imposed, and only English publications were considered.

Since the field of socially assistive robotics is in its infancy, many of the studies are small and exploratory. Nonetheless, they provide an insight into what is currently being researched and the potential applications of SAR in elderly care. For this reason, no publication was excluded on the grounds of methodological quality.

Data extraction

The data extraction form was designed in line with the Participants, Intervention, Comparator and Outcomes approach. This process was conducted by one reviewer (JA) to ensure consistent extraction of all studies. All clinical outcome measures reported in selected studies were extracted. Data extraction included, in addition to outcomes, country in which study was conducted, number of included participants, mean age of participants, gender ratio of participants, specific robot used, cognitive status of participants, settings, study design, study duration and assessment tools.

Duplicate reports of the same study may present in different journals, papers or conference proceedings and may each focus on different outcome measures or include a follow-up data point. To minimise the impact of duplicates, the final set of publications were collated into ‘study groups’ containing duplicate reports. The data extraction process was conducted on the most comprehensive report of a given study.

Data synthesis and analysis

Studies were categorised into groups by the role of the robot in the study. The categories were generated retrospectively by the authors and were not predefined or directly referenced in the original studies themselves.

Some studies used comparable quantitative outcome measures in their assessment of clinical utility of SAR. As different assessment tools were used across studies, a standardised mean score (0–100) was generated to allow comparison across similar assessment tools. The result is a unit-free size.

Results

Search results

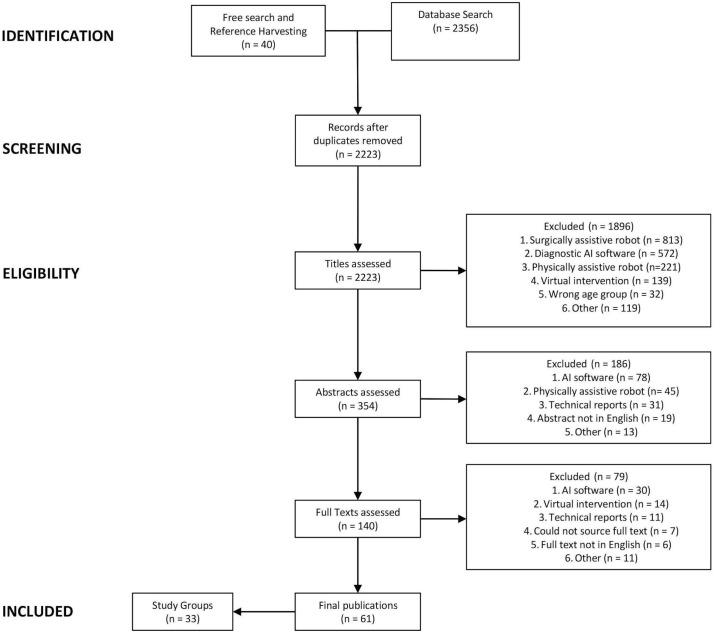

The database search yielded 2356 publications and a further 40 were included from reference harvesting and the free search. Duplicate publications were removed (n=173), and following three screening phases, 61 publications were eligible and included in the review. Once duplicate reports were collated, a total of 33 original studies were identified and subject to detailed review. Descriptions of these studies can be found in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of selected studies

| Role | Ref. | Participants | Setting | Intervention/study design | Duration | Measures | Outcome |

| Affective therapy | Gustafsson et al34 | Four subjects (two men) aged 82–90 years, with dementia | Dementia care home, Sweden | Supervised one-on-one interaction with JustoCat. Pilot study. | One session (unknown time length)/week for 7 weeks. | QUALID, CMAI and interview | 1. No significant changes observed in scales |

| Takayanagi et al22 | 30 subjects (19 with mild/moderate dementia+11 with severe dementia), mean age 84.9 years (mild/moderate), 87.5 years (severe) | Nursing care facility, resident’s room, Japan | Supervised one-on-one interaction with Paro and Stuffed Lion. Pilot study. | One session (~15 min) for each intervention per subject, separated by 3–6 months | Observed behaviour seen in video-recording |

In both groups:

1. Subjects talked more frequently to PARO (P<0.05). 2. Showed more positive emotional expressions with PARO (P<0.01). In mild/moderate group only: 1. Showed more negative emotional expressions with Lion. 2. Frequencies of touching and stroking and frequencies of talking to staff member were higher with Lion. In severe group only: 1. Showed neutral expression more frequently with Lion. |

|

| Bemelmans et al20 | 71 subjects (14 men) with dementia in two groups: therapeutic intervention and care support intervention | Psychogeriatric care institutions, The Netherlands | Supervised one-on-one interaction with Paro or no intervention. Paro either served as a therapeutic or a care support tool in two separate phases of the study. Crossover study. | Five sessions (~15 min)/month for 2 months; each month of therapy was interspersed with a control month. In the therapeutic arm only, additional sessions were given when patient was in distress. | IPPA and Coop/Wonca after each interaction | 1. Therapeutic-related interventions show an increase of IPPA scores by two points (P<0.01). 2. Care support intervention showed no effect. |

|

| Jøranson et al35 36 | 53 subjects (20 men) aged 62–95, with a cognitive impairment (MMSE <25) or diagnosed dementia | Nursing home, separate room, Norway | Supervised group interaction with Paro or TAU. Randomised controlled trial. | Two sessions (~30 min)/week for 12 weeks | Cognitive status, medication, BARS, Norwegian version of CSDD called CDR, QUALID assessed before (T0), after (T1) and at 3-month follow-up (T2) | 1. Reduction in agitation in Paro versus TAU from T0 to T2 (P<0.05). 2. Reduction in depression in Paro versus TAU from T0 to T2 (P<0.05). 3. In those with severe dementia, quality of life scores did not decrease in Paro group from T0 to T2, whereas they did in control. 4. No such difference was found in mild to moderate dementia group. |

|

| Moyle et al37 | 18 subjects, aged >65 years, with dementia | Nursing home, Australia | Supervised group interaction with Paro or reading group. Randomised controlled trial. | Three sessions (~45 min)/week for 5 weeks | Modified QoLAD, RAID, AES, GDS, Revised Algase Wandering Scale–Nursing Home version and OERS | 1. The Paro group had higher QoLAD and OERS-Pleasure scores following the intervention. 2. The Paro group had reduced OERS-Anxiety and OERS-Sadness scores following intervention. |

|

| Wada et al38–45 | 14 subjects (all female) aged 77–98 years, one subject without dementia | Health service facility, Japan | Free group interaction with Paro. Pilot study. | Two sessions (1 hour)/week for 1 year (and a 5-year follow-up) | Face scale, GDS and nursing comments | 1. A tendency to improve depression after 8 weeks. 2. Improvement in mood. 3. Patients did not lose their interest in the long term. |

|

| Thodberg et al13 46 47 | 100 subjects with a mean age of 85.5 years | Nursing homes, Denmark | Supervised one-on-one interaction with Paro, dog or toy cat. Randomised controlled trial. | Two sessions (10 min)/week for 6 weeks | MMSE, GBS, GDS, CAM, sleep data and BMI | 1. Greater interaction with Paro and dog compared with toy. 2. Cognitive and independence scores worsened over study period in all groups (P<0.05). 3. Depression scores improved over study in all group (P<0.05). |

|

| Libin and Cohen-Mansfield23 | Nine subjects (all female) aged 83–98 years, with dementia | Nursing home, USA | Supervised one-on-one interaction with NeCoRo and toy cat. Crossover study. | One session (10 min) for each intervention | ABMI, LMBS and observations | 1. Both cats maintained participant’s interest. 2. Significant increase in pleasure (P<0.01) and interest (P<0.05) scores while playing with NeCoRo. 3. Only the toy cat improved agitation scores (P<0.05). |

|

| Wada et al14 48 49 | 26 subjects (all female) aged 73–93 years, some subjects had dementia | Day service centre, Japan | Free group interaction with Paro. Pilot study. | Three sessions (~45 min)/week for 5 weeks | Summarised POMS, burnout scale for nursing staff, nursing staff comments | 1. Significant improvement in POMS scores (P<0.05). 2. Positive social and psychological effects. |

|

| Wada et al8 50 51 52 53 54 | 23 subjects (six men) mean age 85 | Health service facility, Japan | Free group interaction with Paro or placebo Paro. Randomised controlled trial. | Four sessions (1 hour)/week for 4 weeks | POMS, face scale, urinary tests and nursing comments | 1. Improvement in mood and reduction in depression and dejection levels in both groups. 2. Urinary results suggest Paro interaction reduces stress. |

|

| Valentí Soleret al25 | Phase 1: 20 subjects (10 men), mean age 77.9 years Phase 2: 17 subjects (eight men), mean age 79 years All subjects were diagnosed with dementia |

Day care centre, Spain | Phase 1: Supervised group therapy (cognitive and physical) with NAO. Phase 2: Supervised group therapy (cognitive and physical) with Paro. Crossover study. |

Two sessions (30–40 min)/week for 3 months | GLDS, sMMSE, MMSE, NPI and AI |

Phase 1:

1. Increase in deterioration scores. 2. Significant decrease was seen in irritability scores and total NPI scores. Phase 2: 1. Increase in deterioration scores. |

|

| Lane et al55 | 23 subjects (all men) aged 58–97 years, 19 had been diagnosed with dementia | Veteran residential care facility, USA | Supervised one-on-one interaction with Paro. Pilot study. | Three sessions (>5 min) across 1 year | Behaviour (assessment form designed by authors of study—no formal name) Assessments made before, during and after interaction. | 1. Increase in observed positive affective and behavioural indicators (eg, bright affect, interacting with others, calm). 2. Decrease in observed negative affective and behavioural indicators (eg, anxious, sad and yelling). 3. Those who best responded to Paro were calm and approachable at the before interaction. |

|

| Moyle et al21 | 415 subjects (101 men) mean age 85 years. All subjects were diagnosed with dementia | Long-term care facilities, Australia | Free one-on-one interaction with Paro switched on, Paro switched off or TAU. Cluster-randomised controlled trial. | Three sessions (15 min)/week for 10 weeks | Video observations (at baseline and weeks 1, 5 10 and 15) and CMAI (at baseline and weeks 10 and 15) | 1. Subjects in Paro switched on group were more verbally and visually engaged compared with Paro switched off group. 2. Both Paro switched on and switched off groups had reduced neutral affect compared with TAU group. 3. Paro switched on was more effective than TAU at improving pleasure and agitation. |

|

| Petersen et al56 | 61 subjects (14 men) mean age 84.3 years. All subjects were diagnosed with dementia | Dementia units, USA | Supervised group interaction with Paro or other activity (music, physical activity and mental stimulation). Randomised controlled trial. | Three sessions (20 min)/week for 20 weeks | RAID, CSDD, GLDS, pulse rate, pulse oximetry, GSR and medication | 1. Anxiety scores, depression scores and pulse rate in Paro group all significantly decreased over the study period compared with control group. | |

| Moyle et al12 | Five subjects (all female) mean age 84 years. All subjects were diagnosed with dementia | Nursing home, Australia | Supervised one-on-one interaction with CuDDler. Pilot study. | Three sessions (30 min)/week for 5 weeks | CMAI (before and after each session) | 1. Agitation scores increased in four of the five patients across the 5-week study period. | |

| Cognitive training | Tanaka et al24 | 34 subjects (all female), aged >65 years, living alone | Participant’s home, Japan | Living with Nodding Kabochan or control robot (same design as Nodding Kabochan, but cannot talk or nod). Randomised controlled trial. | 8 weeks | Questionnaires, BMI, cognitive tests, APG and blood and saliva samples | 1. Cognitive scores (MMSE+components of Cognistat) were improved in Nodding Kabochan group. 2. Saliva cortisol level was decreased in Nodding Kabochan group. 3. Higher reports of loss of fatigue, enhancement of motivation and healing in Nodding Kabochan group. |

| Valentí Soler et al25 | Phase 1: 101 subjects (13 men), mean age 84.7 years Phase 2: 110 subjects (11 men), mean age 84.7. All subjects were diagnosed with dementia. |

Nursing home, Spain | Phase 1: Supervised group therapy (cognitive, musical and physical) with Paro or NAO or TAU. Randomised controlled trial. Phase 2: Supervised group therapy (cognitive, musical and physical) with Paro or Dog or TAU. Randomised controlled trial. |

Two sessions (30–40 min)/week for 3 months | GLDS, sMMSE, MMSE, NPI, APADEM-NH and the QUALID |

Phase 1:

1. Decreased apathy in NAO and Paro groups. 2. Increased delusions in the NAO group. 3. Increased irritability in both robot groups. 4. Decrease in scores on the MMSE, but not the sMMSE, in the NAO group. 5. There were no significant differences between NAO and Paro groups. Phase 2: 1. Increase QUALID scores in the Paro group compared with the TAU group 2. Increased hallucinations and irritability in both the Paro and dog groups compared with the TAU group. 3. Increased disinhibition in Paro group compared with dog group. 4. Decreased night-time behaviour disturbances in the Paro group compared with dog group 1. |

|

| Kim et al26 | 71 healthy subjects, aged >60 years, based in community | Assessment centre, South Korea | Supervised group interaction with either Silbot and Mero robots (robot cognitive training) or onscreen quiz (traditional cognitive training) or received no cognitive training (control). Randomised controlled trial. | Five sessions (90 min)/week for 12 weeks | MRI, neuropsychometric tests and Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale | 1. An attenuation of cortical thinning in both intervention groups. 2. Robot therapy showed significantly reduced cortical thinning in the right and left anterior cingulate cortices and small areas of right inferior temporal cortex compared with traditional intervention. 3. Global topological organisation of white matter corticocortical networks was decreased in the control group and the rate of decrease was significantly less in both the intervention groups. 4. Robot therapy had greater nodal strength in the left rectus gyrus. 5. The intervention groups showed greater improvement in the executive function. 6. In the general cognitive and visual memory tasks, the traditional intervention group had greater improvement than in the robot group. 7. The robot group did not outperform the traditional group on any neuropsychological test. |

|

| Tapus et al28 57 58 59 | Three subjects (all female) aged >70 years with dementia (some reports say four subjects, with one male) | Care facility, USA | Individual interaction (musical, cognitive game) with Bandit (compared with an onscreen simulation of Bandit in some reports). Pilot study. | Session (20 min)/week for 12 months | sMMSE, response time, correctness evaluation and questionnaire | 1. Robot encouragement improved response time. | |

| Hamada et al60 | 11 subjects with dementia | Nursing home, Japan | Interaction with AIBO, either individually playing a card game or in a group playing a ball game. Pilot study. | Session/day for 5 days | Frequency of activity in video observation | 1. Improvement in game performance. | |

| Wada et al27 61 | 14 subjects (four men) mean age 79.2, with dementia | Clinic, Japan | Free group interaction with Paro. Pilot study. | One session (20 min) | EEG recording, questionnaire | 1. Improvement in cortical neurons activity of sevens patients, especially in patients who liked the robot. | |

| Social facilitator | Kramer et al29 | 18 subjects (all female) with dementia | Nursing home, participants room, USA | Supervised one-on-one interaction with AIBO, dog or no object. Crossover study. | One visit (~3 min)/week for 3 weeks (each week is a different interaction) | Observed behaviour seen in video-recording | 1. All visits generate interactive behaviour with visitor. |

| Šabanović et al15 | Seven subjects with dementia | Dementia rehabilitation wing, USA | Supervised group interaction with Paro. Pilot study. | One session (30–45 min)/week for 7 weeks | Observed behaviour of primary and non-primary interactor seen in video-recording | 1. PARO increases activity in particular modalities of social interaction, which vary between primary and non-primary interactors. 2. PARO improved activity levels. |

|

| Sung et al16 | 12 subjects (nine men), mean age 77.25 | Residential care facility, Taiwan | Supervised group interaction with Paro. Pilot study. | Two sessions (30 min)/week for 4 weeks | ACIS, Activity Participation Scale | 1. Significant improvement in communication and interaction skills. 2. Significant improvement in activity participation. |

|

| Kidd et al17 62 | 23 subjects, aged 60–104 years, with high functioning in one nursing home and schizophrenia and/or dementia in the other | Nursing homes, US | Supervised group interaction with Paro switched on, Paro switched off or no object. Crossover study. | One session (20 min)/2 weeks (in site A) or per month (in site B) for 4 months (five sessions vs four sessions) | Questionnaire and observation | 1. In switched on Paro group, there was an increase in social interactions, even more in the presence of caregivers or experimenters. 2. Switched on Paro also generated feel-good experiences. |

|

| Sakairi63 | Eight subjects (two men) aged 68–89 years, with dementia | Group home, Japan | One-on-one interaction with AIBO. Pilot study. | One session (30 min) | N-dementia scale, MMSE, behaviour scale and video observation | 1. Improving communication with staff in a group home and establishment of friendly relations with occupants. | |

| Chu et al18 | 139 subjects (95 men) aged from 65 to 90 years, with dementia | Residential care facilities, Australia | Supervised group interaction with Sophie and Jack. Observational study. | Two sessions (4–6 hours) across 5 years | Behaviour (assessment form developed by authors—no formal name). Assessments made every 5 min during session. | 1. Increase in social engagement of subjects across the 5-year study period. | |

| Jøranson et al19 | 23 subjects (seven men) aged from 62 to 92 years. All subjects had a dementia diagnosis | Nursing homes, Norway | Supervised group interaction with Paro. Observational study. | Two sessions (30 min)/week for 12 weeks | Observed behaviour as seen in video recording | 1. Subjects with mild to moderate dementia paid more attention to Paro than those with severe dementia. 2. Over the study period, there was an increase in interactions with other subjects and a decrease in interactions with Paro. |

|

| Companionship | Banks et al30 | 38 subjects | Nursing home, USA | Free one-on-one interaction with AIBO/dog or no object. Randomised controlled trial. | One session (30 min)/week for 8 weeks | Modified LAPS, UCLA LS | 1. Dog and AIBO therapy equally reduced loneliness compared with control (more improvement in most lonely participants; in the control group, the most lonely became more lonely). 2. Residents became significantly and equally attached to AIBO and dog. 3. Attachment was not the mechanism for reduced loneliness in dog or AIBO therapy. |

| Robinson et al31 64 | 34 subjects, aged >55 years | Retirement home, New Zealand | Group or individual interaction with Paro or alternative activity. Randomised controlled trial. | Two sessions (1 hour)/week for 12 weeks | UCLA LS, GDS, QoLAD, interview questionnaire and observations | 1. Loneliness scores significantly decrease in the Paro group compared with control. 2. Residents enjoyed sharing, interacting and talking about Paro. |

|

| Kanamori et al7 | Six subjects (one man) aged >64 years. Five separate control subjects used for CgA measurement. |

Nursing home/participant’s home, Japan | Free interaction with AIBO. Control group for CgA measurements had no intervention. Pilot study. | Four sessions (1 hour)/week for 7 weeks | Scores of emotional words, amount of speech and satisfaction, AOKLS, SF-36 and salivary CgA | 1. Significant reduction of loneliness. 2. Improvement in health-related quality of life. 3. Decrease in salivary CgA, an indicator of sympathetic adrenal system activity. 4. Increase in emotional words, amount of speech and satisfaction exhibited. |

|

| Physiological therapy | Robinson et al32 | 21 subjects (seven men) mean age 84.9 years | Residential care facility, New Zealand | Supervised one-on-one interaction with Paro. Pilot study. | One session (10 min) | Blood pressure reading: before during and after interaction | 1. Significant reductions in systolic and diastolic blood pressure. 2. Reduced systolic blood pressure was sustained after Paro was taken away. 3. Reduced diastolic blood pressure was not sustained after Paro was taken away. 4. Data suggest average heart rate decreased. |

| Wada et al33 65 66 67 68 69 | 12 subjects, aged 67–89 years, with mixed cognitive function | Residential care facility, Japan | Free individual/group interaction with Paro. Pilot study. | One session (9.5 hours)/day for 4 weeks | Urinary tests, interviews and video recording observation | 1. Increase in social interaction and density of social networks. 2. Improvement of subjects’ vital organs reaction to stress. |

ABMI, Agitated Behaviours Mapping Instrument; ACIS, Assessment of Communication and Interaction Skills; AES, Apathy Evaluation Scale; AI, Apathy Inventory; AIBO, Artificial Intelligence Robot; AOKLS, Ando Osada and Kodama Loneliness Scale; APADEM-NH, Apathy Scale for Institutionalized Patients with Dementia Nursing Home version; APG, Accelerated Plethysmography; BARS, Brief Agitation Rating Scale; BMI, body mass index; CAM, Confusion Assessment Method; CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating Scale; CgA, Chromogranin A; CMAI, Cohen Mansfield Agitation Inventory; Coop/Wonca, Mood scale; CSDD, Cornell Scale for Symptoms of Depression in Dementia; GBS, Gottfries-Bråne-Steen Scale; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; GLDS, Global Deterioration Scale; GSR, Galvanic Skin Response; IPPA, Goal attainment scale; LAPS, Lexington Attachment to Pets Scale; LMBS, Lawton’s Modified Behaviour Stream; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; NPI, Neuropsychiatric Inventory; OERS, Observed Emotion Rating Scale; POMS, Profile of Mood States; QoLAD, Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease Scale; QUALID, Quality of Life Scale; RAID, Rating Anxiety in Dementia Scale; SF-36, Short Form Health Survey; sMMSE, Severe Mini Mental State Examination; TAU, treatment as usual; UCLA LS, University of California Los Angeles Loneliness Scale.

The inter-rater agreement between the reviewers were calculated to be 0.91 for the title screen, 0.64 for the abstract screen and 0.89 the final report, demonstrating very good, good and very good correlation between the reviewers, respectively, according to Cohen’s Kappa coefficient.10

Figure 1 outlines a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses schematic flow diagram of the review process and reasons for exclusion.11

Figure 1.

Schematic flow diagram of the review process.

Participants and settings

Across the studies, 1574 participants were included. However, due to inconsistent reporting, overall age and gender information are not available. All participants were considered elderly, and among the studies that reported age information (n=28; 1411 participants), only one participant was under the age of 60 years. The number of participants included in any given study varied from 3 to 415 subjects. In the 24 studies that reported gender information (comprising 1264 participants), 71% of the participants were women. The majority of studies exclusively assessed participants with a dementia diagnosis (n=18; 1036 participants), while a further six studies (151 participants) included some patients with dementia. A large proportion of studies were conducted in Japan (n=10; 178 participants), the USA (n=8; 182 participants) and Australia (n=4; 577 participants). The most common setting was the nursing home (n=17; 621 participants). In total, 11 robot systems were used across the studies. Assessed in 22 of the 31 studies, Paro was the most popular choice of SAR intervention. Robots are divided into those capable of learning responses, such as NAO using closed-loop architecture, and those which cannot, such as Paro, using open-loop architecture. In total, only two closed-loop robots were used (NAO and AIBO) in a total of six studies. Descriptions of individual robot systems reviewed can be found in table 2.

Table 2.

Description of socially assistive robots used in included studies

| Robot | Description | Number used in respective roles | |||||

| Affective therapy | Cognitive training | Social facilitation | Companionship | Physiological therapy | Total | ||

| AIBO | A non-verbal, dog-like robot with a metallic appearance and the ability of sight, walking and interpreting commands. AIBO can learn, mature and, on human interaction, express emotional responses. | – | 1 | 2 | 2 | – | 4 |

| Bandit | A humanoid robot mounted on a wheeled base. Bandit can speak, gesticulate and make facial expressions. | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 |

| CuDDler | A robotic teddy bear able to move its neck, arms and eyelids. CuDDler moves its limbs and vocally interacts. CuDDler can respond appropriately to the pattern and type of touch. | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Jack and Sophie | Sophie and Jack are communication robots that are capable of facial recognition, emotion recognition, vocalisation, gestures, emotive expressions, singing and dancing. | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| JustoCat | A non-verbal, cat-like robot with replaceable fur and similar proportions and weight to a real cat. JustoCat is capable of breathing, purring and meowing and is designed to sit on a persons lap and respond to stroking. | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Mero | A humanoid head mounted on a base, capable of head motion, facial expressions and speech. | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 |

| NAO | A humanoid robot, 58 cm tall, capable of walking, speech, gesticulation and dance. NAO is able to interact with people and can develop new skills and become personalised. | 1 | 1 | – | – | – | 2 |

| NeCoRo | A non-verbal, cat-like robot designed to move and look like a real cat. NeCoRo can interpret its surroundings and move accordingly. NeCoRo can express emotion. | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Nodding Kabochan | A small robot, with the appearance of a child-like teddy, that can talk, sing and nod. It is designed to communicate with users. Nodding Kabochan can play exercise and singing games with the user. | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 |

| Silbot | A penguin-like robot that can speak and detect faces. Silbot can engage with users in conversation, games and provide care through drug regimen reminders. | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 |

| Paro | A non-verbal, seal-like robot with the ability to move its head and tail, blink and make sounds and has five sensory modalities: light, sound, temperature, posture and tactile. Paro will respond to being held or stroked and can learn to respond to its name. Paro has its own rhythms; will at times be playful and at other times sleepy and inactive. table 2: description of Socially Assistive Robots used in Included Studies. | 9 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 17 |

Identified roles of SARs

Eligible studies were organised into sets by the role assumed by SAR. Five roles were identified: affective therapy, cognitive training, social facilitator, companionship and physiological therapy. Specific details of the studies below, such as assessment tools or subject demography, are described in table 1.

Affective therapy

Fifteen studies (889 participants) evaluated the effect SAR can have in improving the general mood and well-being of elderly participants, or its ability to overcome episodes of mood disturbance. In this review, this role is collectively termed affective therapy. Nine of these studies (650 participants) were conducted on participants diagnosed with dementia. In total, 11 reported positive findings including reductions in depression scores, agitation scores and increases in quality of life scores. While these studies were evaluating similar effects of SAR, their intervention design can broadly be divided into two types: one-on-one interactions with SAR or group interactions with SAR.

Eight studies (657 participants) assessed SAR in one-on-one settings, whereas the remaining seven studies (232 participants) had group settings. All of the group setting studies reported positive findings, including reduced agitation and depression levels and higher expression of positive emotions. Of the eight one-on-one interaction studies, only five report positive findings. Indeed, two of these studies12 13 report negative findings with increased agitation and worsening dementia, respectively.

These contrasting set of results could indicate a mechanism of how elderly users gain emotional benefit from SAR. A Japanese pilot study14 assessed group interactions of 26 subjects with Paro and found significant improvements in mood scores during the intervention period. Of note, the authors commented on improved sociability between subjects. As discussed later, several studies15–19 demonstrate that SAR can increase the sociability of subjects within groups, which may play a direct role in the mood changes seen here.

Notwithstanding this, however, a Dutch crossover study20 compared two types of one-on-one intervention: therapeutic interventions (Paro introduced at times when subject was distressed) and care support interventions (Paro introduced to facilitate activities of daily living). Only the therapeutic intervention showed a significant improvement in the mood score (P<0.01). This suggests that perhaps while group interventions may be better at generating positive emotions, one-on-one interventions may be appropriate to remedy negative emotions.

Some studies in this set also investigated how SAR compared with soft toys in improving general mood and well-being of participants. A large Australian randomised controlled trial (RCT)21 of 415 participants with dementia compared one-on-one interventions with Paro switched ‘on’ and Paro switched ‘off’ (placebo Paro) to identify if Paro’s additional social capabilities translated into any positive outcomes. The study found Paro was more effective than usual care in improving pleasure and agitation but was no different to placebo Paro. Similarly, a Japanese study8 compared the effect of group interactions with Paro and placebo Paro and again did not demonstrate any differences between the groups.

These results are mimicked by a Danish RCT13 of 100 subjects, which compared interactions with Paro, a living dog or soft toy cat. The study found intervention type did not affect cognitive state, independence or depression scores and did not affect sleep quality. However, depressive scores improved compared with baseline scores in all groups (P<0.05).

Indeed, only two small pilot studies found differences between SAR and soft toys. The first22 showed subjects engaged more with Paro (P<0.05) and showed more positive emotional expressions with Paro (P<0.01) when compared with a stuffed lion. The second23 was a study on participants with dementia; it showed that agitation scores were only significantly decreased in a toy cat (P<0.05), whereas NeCoRo (SAR—cat-like robot) only improved scores of pleasure and interest (P<0.01 and P<0.05, respectively).

Cognitive training

Six studies (344 participants) assessed whether SAR can improve aspects of cognition, such as working memory or executive function, and as such this review has termed this set cognitive training. This set included four studies (239 participants) that assessed elderly subjects with dementia, and two studies (105 participants) that assessed elderly subjects who were cognitively intact. Several robot types have been used in this set including two closed loop robots capable of learnt responses. This means that while broad conclusions surrounding the role of SAR in cognitive training can be made, the evidence for any individual robot system is limited. Five of the six studies (133 participants) concluded with positive findings, although there is a breadth of outcome measures used as surrogate markers for cognitive improvement.

Two studies used cognitive tests, such as Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) as the primary outcome measure to assess the impact of SAR interactions. The first was a RCT24 of 34 cognitively healthy subjects in Japan using the Nodding Kabochan as the SAR intervention. Subjects either received the fully functional Nodding Kabochan or a non-functional Nodding Kabochan (control) for 8 weeks. All interactions were one on one with the participant and the SAR in the participants’ home. Only subjects receiving the functional Nodding Kabochan demonstrated an improved cognitive function score (P<0.01) after the study period. This result contrasts with the conclusion of the previous set, affective therapy, where it was difficult to distinguish the positive effects between functional SAR and placebo toys. The distinction here may be that the Nodding Kabochan robot is a communication robot that can talk and sing with the user, a function that a placebo toy is incapable of. The communication itself may be key to this study’s findings.

The other study that used cognitive tests as an outcome measure for cognition was a two-phase block RCT.25 This Spanish study involved 101 and 110 subjects with dementia, in the respective phases, and assessed the cognitive effects of group interactions with SAR. In phase 1, the study compared open-loop system robot, Paro, with closed-loop robot, NAO, and a control group treatment as usual. Compared with control group, phase 1 showed a decrease in cognitive function scores in the NAO group only (P<0.05) at follow-up. Notably, there were no significant differences between NAO and Paro groups at follow-up. This set of results contrasts with the previous study conducted on cognitively healthy subjects in one-on-one settings. Given different robots systems have been used in the studies, it is difficult to establish which factor is responsible for differing results.

Two studies used neuroimaging modalities as outcome measures of interactions with SAR. The first was a South Korean study26 that used MRI in a RCT of 71 cognitively healthy subjects. The primary outcome measure was change in cortical thickness in brains of participants over the 12-week study period. Subjects were randomised into three arms: (1) robot-assisted group training using Silbot and Mero (SAR), (2) traditional intervention training, using computer software or (3) non-intervention arm - control. The study showed attenuation of cortical thinning on MRI in both intervention groups (P<0.05) and estimated it would take 15.3 months for intervention groups to reach the same level of cortical thinning as controls. This study also used neuropsychiatric tests as a secondary outcome measure. Both intervention groups showed greater improvement in the executive function scores than control group (P<0.001). However, in the general cognitive and visual memory tasks, the traditional intervention group had greater improvement than in the robot group. Indeed, the robot group did not outperform the traditional group on any neuropsychological tests. Both Silbot and Mero are communication robots, like the Nodding Kabochan, which may underpin the improvements in executive function. Nonetheless, the SAR arm did not prove to be any more effective than traditional computer software in either outcome measures for cognitive function.

The other study to use a neuroimaging modality was a Japanese pilot study27 of 14 subjects with dementia. This study investigated the neuropsychological influence of Paro within an interactive group setting by analysing the electroencephalogram (EEG) recordings. They found an increase in cortical neuronal activity in seven participants, particularly in participants who liked Paro. It is unclear what the clinical meaning of this finding is, and without a control group, one cannot distinguish the effect of SAR from any other stimulating activity on EEG.

The two final studies used game performance as a surrogate marker for cognitive function in participants with dementia. These were very small studies without control groups. The first28 included three subjects and found that verbal encouragement from SAR (Bandit) improved response time in a game quiz, while the second study, with 11 participants, concluded the participants’ performance in group ball games and individual card games improved following interactions with SAR (AIBO). Again, the clinical utility of this is unclear, and without objective outcome measures or control groups, there is little that can be learnt from these studies.

Social facilitator

Seven studies (230 participants) assessed the utility of SAR as facilitators for improved sociability between subjects or between subjects and other people. As such, this review has titled this role social facilitator. All of these studies concluded that the respective SAR intervention improved sociability of participants. Five of these studies (210 participants) were conducted with participants who had been diagnosed with dementia. Four of the studies used Paro as the SAR intervention, and two used AIBO, the robotic dog, which allowed for a greater degree of comparison between the studies. The final study used Sophie and Jack as the SAR intervention.

Most studies used observed behaviour changes on video recording or via a live assessor during the interaction period. One study16 used a validated communication scale to assess how group Paro interactions affected sociability. The study concluded that after the 4-week programme, a significant improvement in communication and interaction skills were exhibited by subjects (P<0.05) and an increase in activity participation (P<0.05).

Two studies compared SAR with comparative soft toys/animals. The first was a crossover study17 of 23 subjects in the USA. Subjects were grouped into sessions with Paro, placebo Paro or no object. The study concluded that the group with Paro engaged in more social interactions than the group with placebo Paro. This suggests that the sociability effects are associated with SAR itself. The authors note that the novelty around SAR may have contributed to the excitement manifested in increased social engagement. However, as this study was conducted over 4 months, any novelty effects would not likely have been sustained.

The other comparative study was another crossover study29 in the USA, which involved 18 female subjects with dementia. Subjects were divided into sessions with AIBO, a real dog or no object. The study concluded that although all visit types with AIBO, a dog or no object stimulated social interaction by the subject, there were no significant differences in the frequency of social behaviours exhibited by the subjects between visit types.

A similar US pilot study15 of seven subjects with dementia was instead conducted in a group setting. Subjects within a group were divided into primary users, those individuals who engaged with Paro at any one time, or non-primary users who were defined as everyone else in the group. The study showed an increase in social interaction over the 7-week period between primary and non-primary users towards each other and towards staff.

This study’s results are reflected in two larger, more recent studies that also investigate effects of group interactions with SAR on participants with dementia. The first is an Australian study18 of 139 participants conducted over 5 years with Sophie and Jack. The study reported that social engagement increased over the study period. The second was a Norwegian study19 with 23 participants that evaluated the effects of group interactions Paro on those with mild to moderate dementia compared with those with severe dementia. The study found that those with mild to moderate dementia paid more attention to Paro than those with severe dementia. The authors note that SAR interventions may need to be more tailored towards the degree of dementia severity. Another finding was that over the 12-week study period, there was a reported increase in interactions with other subjects and a decrease in interactions with Paro.

Companionship

Three studies (78 participants) assessed the utility of SAR in overcoming the feeling of loneliness and social isolation in the elderly. These studies are collected into a set this review has titled the companionship role. All three of the studies examining SAR in this role showed reductions in loneliness scores. None of these studies were conducted on patients with diagnosed dementia. Two studies used AIBO as the intervention, while the third used Paro.

Only one study assessed this in a one-on-one setting. This was a RCT30 of 38 subjects in the USA. Subjects were randomised to have weekly one-on-one sessions with a real dog, AIBO or no object (control). Subjects in the dog or AIBO group were significantly less lonely than those in the control group at week 7 (P<0.05, respectively). In both intervention groups, there was a higher attachment score compared with the control group. No significant differences were found between the dog and AIBO groups in the assessment of loneliness or attachment. This is an important finding that suggests an artificial animal (SAR) can be as effective a companion as a pet.

The other two studies were conducted in a group setting. The first study was a pilot study7 of 11 subjects in Japan using AIBO. Mean loneliness scores after the session were significantly lower than those before the session (P<0.05), although longer term benefits were not established. The second was a larger RCT31 of 34 subjects in New Zealand investigated the effects of Paro on loneliness. Subjects were randomised into a Paro group or a control group that attended normal activities. Subjects in the Paro group had a significantly greater decrease in loneliness score at the 12-week follow-up than the control group (P<0.05). This indicated that sustained effects can be achieved.

The last two studies do show promising results; however, in the context of the previous set of studies, the decreased sense of loneliness may result from increased sociability in the group setting. Sociability was not measured in either study and therefore may act as a confounder.

Physiological therapy

Two studies (33 participants) investigated the effects of SAR on physiological markers, and as such, this review titles this set physiological therapy. This clinical applicability of this set is less clear but does raise some questions that future studies may be able to answer. Both of these studies used Paro as the SAR intervention.

The first was a pilot study32 of 21 subjects in New Zealand and investigated the effect of Paro on blood pressure and heart rate. Subjects had a single 10 min session with Paro where they were free to interact with the robot. Blood pressure and heart rate was recorded before (T1), immediately after (T2) and 5 min after (T3) the 10 min interaction. Overall, no significant changes in blood pressure or heart rate were demonstrated; however, the study decided to exclude four residents who did not interact or touch the robot. Subsequently, significant decreases in systolic blood pressure (P<0.05) from T1 to T2 were shown, and such decreases were sustained at T3 measurement. Similarly, significant decreases in diastolic blood pressure (P<0.05) from T1 to T2 were shown; however, this decrease was not sustained at T3. Between T1 and T3, heart rate significantly decreased (P<0.05).

In the other study33 of 12 subjects in Japan, physiological effects of interacting with Paro were investigated. Compared with baseline readings, a significant increase in the ratio of urinary 17-ketosteroid:17-hydroxycorticosteroid (P<0.01), by week 4 of Paro being introduced, was found. The authors suggest this confers an improved physiological reaction to stress. A confounder noted was an increase in social interactions with other residents (P<0.05) by week 4, compared with baseline. It is also not clear from this study if Paro played any role in the increased sociability of residents; however, in the context of other studies on the topic, it seems likely.

These two studies do not provide much indication of the clinical use of SAR; however, they do give a direction for what future studies could investigate further.

Quantitative comparison

Several studies reported comparative quantitative data by using the same or similar assessment scales to others within their role category. The data from these studies have been reproduced from the studies and are compiled in tables 3–5. As different assessment tools were used across studies, a standardised mean score (0–100) was generated to allow comparison across similar assessment tools. Five comparable studies were identified in the affective therapy, each using a mood scale to assess either anxiety or depression or both, giving rise to seven comparable sets of data. Of these, five showed significant improvements in the mood scores either in the robot intervention group or in the follow-up score, depending on study design.

Table 3.

Data extracted from comparable studies in affective therapy studies

| Affective therapy Mood scores | |||||||||

| Study | Number of subjects | Outcome scale | Control | Intervention | P value | ||||

| Mean baseline score (SD) | Mean follow-up score (SD) | Change in mean score | Mean baseline score (SD) | Mean follow-up score (SD) | Change in mean score | ||||

| Gustafsson et al34 | 4 | CMAI | – | – | – | 12.6 (6.3) | 13.3 (6.6) | 0.7 | 0.88* |

| Jøranson et al35 | 53 | BARS | 22 (19) | 23.3 (22) | 1.3 | 20.1 (12.8) | 13.7 (11.7) | −6.4 | 0.044† |

| Jøranson et al35 | 53 | CSDD | 18.2 (12.3) | 24.5 (17.3) | 6.3 | 23.7 (12.9) | 18.9 (16.8) | −4.8 | 0.019† |

| Petersen et al56 | 61 | CSDD | – | – | −2.1 | – | – | −7.4 | 0.001† |

| Petersen et al56 | 61 | RAID | – | – | −0.7 | – | – | −3.1 | 0.003† |

| Moyle et al37 | 18 | GDS | – | 28.7 (23.3) | – | – | 31.3 (19.3) | – | 0.72‡ |

| Thodberg et al13 | 100 | GDS | – | – | – | 13.3 (6.7; 33.3)§ | 13.3 (6.7; 23.3)§ | – | <0.05¶ |

*Study compares mean baseline score in intervention group to mean follow-up score in the intervention group.

†Study compares change in mean score from baseline to follow-up in control group to change in mean score from baseline to follow-up in intervention group.

‡Study compares mean follow-up score of control group to mean follow-up score of intervention group.

§Study compares median baseline score in intervention group to median follow-up score in the intervention group.

¶Median and IQR reported.

BARS, Brief Agitation Rating Scale; CMAI, Cohen Mansfield Agitation Inventory; CSDD, Cornell Scale for Symptoms of Depression in Dementia; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; RAID, Rating Anxiety in Dementia Scale.

Table 4.

Data extracted from comparable studies in cognitive training studies

| Cognitive training Cognition scores |

P value | ||||||||

| Study | Number of subjects | Outcome scale | Control | Intervention | |||||

| Mean baseline score (SD) | Mean follow-up score (SD) | Change in mean score | Mean baseline score (SD) | Mean follow-up score (SD) | Change in mean score | ||||

| Tanaka et al24 | 34 | MMSE | – | – | – | 94.0 (5) | 99.0 (2.3) | 5 | <0.01* |

| Valentí Soler et al25 Phase 1 | 101 | MMSE | 12.1 (18.1) | 10.4 (15.7) | −1.7 | 11.8 (17.3) | 8.1 (15.0) | −3.7 | 0.022† |

| Valentí Soler et al25 Phase 2 | 110 | MMSE | 12.1 (18.1) | 10.4 (15.7) | −1.7 | 10.7 (16.5) | 9.1 (15.7) | −1.6 | 0.282† |

| Kim et al26 | 71 | ADAS-Cog | – | – | – | 89.9 (5.1) | 92.6 (4.0) | 2.7 | <0.001* |

*Study compares mean baseline score in intervention group to mean follow-up score in the intervention group.

†Study compares change in mean score from baseline to follow-up in control group to change in mean score from baseline to follow-up in intervention group.

ADAS-Cog, Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – cognitive subscale; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination.

Table 5.

Data extracted from comparable studies in companionship studies

| Companionship Loneliness scores | |||||||||

| Study | Number of subjects | Outcome scale | Control | Intervention | P value | ||||

| Mean baseline score (SD) | Mean follow-up score (SD) | Change in mean score | Mean baseline score (SD) | Mean follow-up score (SD) | Change in mean score | ||||

| Banks et al30 | 38 | UCLA LS | – | – | 5.7 (1.3) | – | – | −6.0 (2.7) | <0.05* |

| Robinson et al31 | 34 | UCLA LS | – | – | 3.8 (10.3) | – | – | −9.0 (12.6) | 0.03* |

| Kanamori et al7 | 5 | AOKLS | – | – | – | 3.3 (2.2) | 1.0 (1.3) | – | <0.05† |

*Study compares change in mean score from baseline to follow-up in control group to change in mean score from baseline to follow-up in intervention group.

†Study compares mean baseline score in intervention group to mean follow-up score in the intervention group.

AOKLS, Ando Osada and Kodama Loneliness Scale; UCLA LS, University of California Los Angeles Loneliness Scale.

Four comparable studies were identified in the cognitive training set of studies, and of these, three studies showed significant improvements in the cognitive scores. Of note, the two phases of the Spanish paper25 have been listed as two separate sets of data as they are different studies with different interventions and different subject numbers; they both use the same control data, however, as seen on table 4.

Finally, three studies with comparable data were identified in the companionship set of studies, each of which used validated loneliness scales. All of these studies showed significant improvements in loneliness scores in the robot intervention group or in the follow-up score, depending on study design.

No comparative data were identified in the social facilitator or physiological therapy groups.

Discussion

The aim of this review is to identify the roles SAR could play in elderly care. Despite the infancy of this field, the qualitative amalgamation of the studies demonstrated five roles for SAR.

Evaluation of SAR technology

This review identifies five roles for SAR in elderly care: affective therapy, cognitive training, social facilitation, companionship and physiological therapy. These roles provide a comprehensive classification of how this technology has been used in social and physical care to date.

The first set of studies demonstrated that SAR can be used to improve the overall sense of well-being of users and alleviate acute states of mood disturbance. Interestingly, interactions conducted in a group setting proved to be more consistently effective than one-on-one interactions. However, a study20 showed that one-on-one interventions were useful in alleviating states of distress. This result may apply to patients with delirium, and future studies are required to explore this possibility. The overall picture suggests that while SAR is capable of improving mood of subjects, it does not seem to be much better than a comparative soft toy or placebo robot. This is demonstrated in patient groups with and without dementia.

This was not true for the second set, cognitive training, where communication robots were significantly more effective at improving cognitive outcome measures than soft toys. The clearest evidence for SAR in improving cognitive function was found in those who are cognitively healthy. While positive findings have been found in participants with dementia, obscure outcome measures make it difficult to interpret the meaning of the findings. The South Korean study26 showed that computer programmes are at least as effective as SAR interventions and may raise doubts about the cost-effectiveness of using SAR to only improve elderly users cognitive function.

All the studies in the social facilitator set demonstrated improved sociability. This is demonstrated in subjects with and without dementia and across three robot systems (AIBO, Paro and Sophie and Jack). When compared in group settings, SAR was shown to be more effective than a comparator, such as a soft toy. In one US study,29 subjects were divided into one-on-one sessions with AIBO, a real dog or no object at all, and while all sessions increased frequency of exhibited social behaviour, the study concluded no significant differences between session type. Conversely, in a different US study,17 participants had group interactions with Paro, placebo Paro or no object. The study concluded that the group with Paro engaged in more social interactions than the group with placebo Paro. This suggests that the sociability effects are associated with a group setting, and perhaps in the absence of a group of users, these effects may not exist.

The companionship set all showed positive findings. However, two studies were conducted in group settings, and the observed improved loneliness scores may be confounded by the increased sociability seen in aforementioned studies. This set has far fewer studies than the other sets generated in this review; however, the findings are insightful. If animal-like SAR can be as much a companion as a pet, then such technology may have particular utility in care homes, where health and safety concerns regarding pets, such as allergies and infection risks, restrict their use.

The final set, physiological therapy, did show positive findings; however, these findings are clinically uninterpretable. Nonetheless, these studies create new questions about the use of SAR for future studies to address. For example, one study32 demonstrated short-term reductions in blood pressure and heart rate following Paro interactions. The potential implications of these results are twofold: this short-term reduction in cardiovascular markers could reflect results seen in the affective therapy set, which show calming effects of Paro. Additionally, it may be the case that these reductions can be sustained for the long term and that SAR may have a role as a non-pharmacological intervention for hypertension. Future studies may benefit from incorporating blood pressure and heart rate outcome measures, alongside other metrics in longer term studies.

While the utility of SAR in affective therapy or cognitive training can be replaced by cheaper, existing alternatives (eg, soft toys or computer software), the main value of SAR may lie in its multidomain functionality. This review has identified five such domains where a single intervention may be of simultaneous value.

Quality of selected studies

Of all 33 included studies, 11 were RCTs, 12 included more than 30 subjects and 16 had a comparative intervention. These metrics are not in their own right indicative of the quality of the studies; however, together they do provide a general picture. The quality of studies is not evenly distributed across the set. Of the RCTs, six are in the affective therapy set, while there are none in the social facilitator set. Similarly, nine studies in the affective therapy set have a comparative intervention compared with two in the social facilitator set.

This review did not exclude studies based on methodology. The rationale is that low-quality studies can offer an insight into the potential utility of SAR and guide study design improvements for future studies. For example, a companionship role is a popular concept for SAR among commentators in the literature, but very few studies demonstrating this have been conducted. Evidence supporting a companionship role is socially desirable because of its applicability to serve the elderly population. As reported by one of the selected studies,30 AIBO, the robotic dog, was as effective a companion as a real dog. This has real implications for its use, specifically where a real animal companion may be inappropriate.

Although no studies were excluded on the basis of quality, there are several underlying methodological limitations facing the selected studies that need to be addressed. Low-quality data complicate the task of establishing clinical applications of SAR. It also risks undermining the field’s efforts or sensationalising exploratory research. Another limitation is the narrow set of robots assessed, primarily Paro. This restricts the applicability of results to wider SAR systems with different functionality.

There is also a concern for cultural bias as around a third of the studies were conducted in Japan alone. Although more recent studies have been conducted in other cultural environments, most notably the USA and Australia, it is not clear if the results are universally applicable. Additionally, there is evidence of gender bias. Around two-thirds of the participants were women. This is a concern since men and women as populations have been shown to regard robot technology differently,70 and therefore some of the reported findings may be exaggerated or diminished by the participant composition.

Another common study design issue relates to the supervision of interactions that are present in 20 of the included studies. Although supervision ensures safety for the user, it risks altering how the participant interacts with the robot and may change how the participant reports the robot’s utility, known as the Hawthorn Effect. While this is difficult to control for when the study is not randomised and no comparator is used, direct supervision may lead to subjects reporting greater positive effects than is necessarily the case. An example where this may be the case is a US study29 where subjects were divided into supervised sessions with AIBO, a real dog, or no object at all. One would anticipate that sessions with an object (AIBO or a soft toy) would stimulate a greater behavioural response than no object at all. However, the study concluded there were no significant differences between the responses to the sessions, irrespective of whether an object was present or not. This suggests that the positive findings were completely independent of the intervention and may instead be a consequence of supervision.

Another main limitation of the selected studies is the nature of chosen outcome measures. They are often abstract, with a limited number of studies identifying a direct clinical need or problem. Although around half of the studies included a comparator intervention, it often involved uninspiring activities or no activity at all. This is an unfair comparison and may inflate the value attributed to the results. As momentum grows behind SAR, these study design flaws will need to be addressed if the technology is going to play a clinical role in the future.

Review limitations

The primary limitation of this review is the validity of the categorisation of studies into the defined roles. The roles were created retrospectively, as part of a discovery process on extracting data from the final set of studies. While they have utility in evaluating the state of the field and providing defined expectations for the technology, they have generalised sets of studies that are very different in quality, design and sometimes outcome. There is also the issue that some studies demonstrated several roles for SAR. The studies were categorised on the basis of the the primary outcome measures, irrespective of whether a secondary outcome measure would fit into another set. A consequence of this is that the weight of data in the respective roles may be misleading. All outcomes have been reported in table 1 for purposes of data transparency.

Furthermore, this review has an inadvertent risk of excluding relevant papers in the screening phase. Although high concordance between the reviewers was reported, the large volume of studies that had to be reviewed invites the possibility that relevant publications were excluded. The main reason for the high exclusion rate was because the broad search criteria identified irrelevant robot interventions, such as surgical robots or telecommunication devices. It is unlikely, however, that an additional study would have changed the conclusions of this review.

Finally, the comparison of assessment values between studies illustrated in tables 3–5, aimed to provide some comparison between studies where different outcome measures were used. The comparison does have limitations, because although each assessment tool was scaled from 0 to 100, a score of 50 in one measure does not necessarily correlate to 50 in a different scale. This has made it difficult to reach broad conclusions about the sets of studies.

Future of the field

In order to achieve successful application of SAR in elderly care, future studies should be more conscious of the outcome measure chosen and its translation into care. Some studies used surrogate measures such as frequency of laughter,22 or performance in particular games.60 While these may be desired outcomes, it is not clearly demonstrated how they meet quantifiable needs of the elderly population. It is likely that any application of SAR will incorporate several of the previously defined roles. Therefore, larger studies should assess the intervention’s impact in the context of these clear roles with validated outcome measures. For example, one study24 involved a robot staying at home with the elderly participants for 8 weeks and assessed its impact using questionnaires, cognitive tests, blood and saliva samples. While the study demonstrated an improvement in cognitive scores and a reduction in saliva cortisol, it did not assess whether living with a robot for 8 weeks had any impact on loneliness. Larger RCTs using valid comparators are needed to definitively show where SAR is and is not useful in elderly care.

Conclusion

SARs have shown potential in elderly care which, in light of recent demographic shifts, promises to reform the delivery of care for the elderly. Although many of the studies described have methodological issues, the size and quality of studies are improving. This review has qualitatively assessed the existing research and comprehensively outlined the state of the field as it stands. In establishing the five roles to which SAR can be ascribed, this review intends not to restrict ambition but to provide a basis for clinical applicability and design of future studies. This review urges that new studies should be clearer about the precise role any robot intervention intends to serve and use validated measures to assess their effectiveness. Future studies need to demonstrate how SAR can solve real problems in order to shift from novelty to functionality in elderly care.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Design of the review: JA and MPV. Data collection: JA and AA-H. Data analysis and interpretation: JA, TN and MPV. Drafting the article: JA, AA-H and TN. Critical revision of the article: JA, TN and MPV. Final approval of the version to be published: MPV.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional unpublished data from this review.

Collaborators: Peter Forrest; Sundhiya Mandalia.

References

- 1.United Nations. World Population Prospects. 2015;1 http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/Publications/Files/WPP2015_Volume-I_Comprehensive-Tables.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas J. Insights into Loneliness, Older People and Well-being. 2015:1–10 http://backup.ons.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2015/10/Insights-into-Loneliness-Older-People-and-Well-being-2015.pdf.

- 3.Victor C, Scambler S, Bond J, et al. social isolation and living alone in later life. Rev Clin Gerontol 2000;10:407–17. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 2010;7:7 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hegel F, Muhl C, Wrede B, et al. Understanding Social Robots. Second Int Conf Adv Comput Interact 2009:(Section II):169–74. 10.1109/ACHI.2009.51 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reiser U, Jacobs T, Arbeiter G, et al. Care-O-bot ® 3 – Vision of a Robot Butler. 2013;7407:97–116. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanamori M, Suzuki M, Oshiro H. Pilot study on improvement of quality of life among elderly using a pet-type robot. IEEE Int Conf Robot Autom 2003:107–12. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wada K, Shibata T, Saito T, et al. Effects of Robot Assisted Activity to Elderly People who Stay at a Health Service Facility for the Aged. IEEE/RSJ Int Conf Intell Robot Syst 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, 2011. http://handbook.cochrane.org

- 10.Orwin RG, Vevea JL. Evaluating Coding Decisions In: The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis, 1994:177–200. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement (Reprinted from Annals of Internal Medicine). PLoS Med 2009;89:873–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moyle W, Jones C, Sung B, et al. What Effect Does an Animal Robot Called CuDDler Have on the Engagement and Emotional Response of Older People with Dementia? A Pilot Feasibility Study. Int J Soc Robot 2016;8:145–56. 10.1007/s12369-015-0326-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thodberg K, Sorensen LU, Christensen JW, et al. Therapeutic effects of dog visits in nursing homes for the elderly. United Kingdom: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2015:289–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wada K, Shibata T, Saito T, et al. Effects of robot assisted activity for elderly people at day service center and analysis of its factors. Proc 4th World Congr Intell Control Autom 2002;2:1301–5. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Šabanović S, Bennett CC, Chang WL, et al. PARO robot affects diverse interaction modalities in group sensory therapy for older adults with dementia. IEEE Int Conf Rehabil Robot 2013;2013:6650427 10.1109/ICORR.2013.6650427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sung HC, Chang SM, Chin MY, et al. Robot-assisted therapy for improving social interactions and activity participation among institutionalized older adults: a pilot study. Asia Pac Psychiatry 2015;7:1–6. 10.1111/appy.12131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kidd CD, Taggart W. Turkle S. A Sociable Robot to Encourage Social Interaction among the Elderly. IEEE Int Conf Robot Autom 2006:3972–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chu MT, Khosla R, Khaksar SM, et al. Service innovation through social robot engagement to improve dementia care quality. Assist Technol 2017;29:8–18. 10.1080/10400435.2016.1171807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jøranson N, Pedersen I, Marie A, et al. Group activity with Paro in nursing homes : systematic investigation of behaviors in participants. 2016;2017:1345–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bemelmans R, Gelderblom GJ, Jonker P, et al. Effectiveness of Robot Paro in Intramural Psychogeriatric Care: A Multicenter Quasi-Experimental Study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2015;16:946–50. 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moyle W, Jones CJ, Murfield JE, et al. Use of a Robotic Seal as a Therapeutic Tool to Improve Dementia Symptoms: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;18:766–73. 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takayanagi K, Kirita T, Shibata T. Comparison of Verbal and Emotional Responses of Elderly People with Mild/Moderate Dementia and Those with Severe Dementia in Responses to Seal Robot, PARO. Front Aging Neurosci 2014;6:257 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Libin A, Cohen-Mansfield J. Therapeutic robocat for nursing home residents with dementia: preliminary inquiry. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2004;19:111–6. 10.1177/153331750401900209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tanaka M, Ishii A, Yamano E, et al. Effect of a human-type communication robot on cognitive function in elderly women living alone. Med Sci Monit 2012;18:CR550–7. 10.12659/MSM.883350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valentí Soler M, Agüera-Ortiz L, Olazarán Rodríguez J, et al. Social robots in advanced dementia. Front Aging Neurosci 2015;7:133 10.3389/fnagi.2015.00133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim GH, Jeon S, Im K, et al. Structural brain changes after robot-assisted cognitive training in the elderly: A single-blind randomized controlled trial. Alzheimer’s & Dementia 2013;9:P476–7. 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.05.971 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wada K, Shibata T, Musha T, et al. Robot Therapy for Elders Affected by Dementia 2014 IEEE Long Isl Syst Appl Technol Conf LISAT. 2014.

- 28.Tapus A. Improving the quality of life of people with dementia through the use of socially assistive robots. Proc - 2009 Adv Technol Enhanc Qual Life, AT-EQUAL 2009. 2009:81–6.

- 29.Kramer SC, Friedmann E, Bernstein PL. Comparison of the Effect of Human Interaction, Animal-Assisted Therapy, and AIBO-Assisted Therapy on Long-Term Care Residents with Dementia. Anthrozoos 2009;22:43–57. 10.2752/175303708X390464 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Banks MR, Willoughby LM, Banks WA. Animal-assisted therapy and loneliness in nursing homes: use of robotic versus living dogs. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2008;9:173–7. 10.1016/j.jamda.2007.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robinson H, Macdonald B, Kerse N, et al. The psychosocial effects of a companion robot: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2013;14:661–7. 10.1016/j.jamda.2013.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robinson H, MacDonald B, Broadbent E. Physiological effects of a companion robot on blood pressure of older people in residential care facility: a pilot study. Australas J Ageing 2015;34:27–32. 10.1111/ajag.12099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]