Abstract

Objectives

To investigate differences in ulcer healing time and waiting time between video consultation and inperson assessment for patients with hard-to-heal ulcers.

Setting

Patients treated at Blekinge Wound Healing Centre, a primary care centre covering the whole of Blekinge county (150 000 inhabitants), were compared with patients registered and treated according to the Registry of Ulcer Treatment, a Swedish national web-based quality registry.

Participants

In the study for analysing ulcer healing time, the study group consisted of 100 patients diagnosed through video consultation between October 2014 and September 2016. The control group for analysing healing time consisted of 1888 patients diagnosed through inperson assessment during the same period. In the study for analysing waiting time, the same study group (n=100) was compared with 100 patients diagnosed through inperson assessment.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Differences in ulcer healing time were analysed using the log-rank test. Differences in waiting time were analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Results

Median healing time was 59 days (95% CI 40 to 78) in the study group and 82 days (95% CI 75 to 89) in the control group (P<0.001). Median waiting time was 25 days (range: 1–83 days) in the study group and 32 days (range: 3–294 days) for patients diagnosed through inperson assessment (P=0.017). There were no significant differences between the study group and the control group regarding age, gender or ulcer size.

Conclusions

Healing time and waiting time were significantly shorter for patients diagnosed through video consultation compared with those diagnosed through inperson assessment.

Keywords: ehealth, telemedicine, leg ulcer, registries, wound healing

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The use of a large, nationally representative sample of patients with hard-to-heal ulcers gives increased generalisability.

A well-known technical system was used for video communication.

All patients diagnosed through video consultation were assessed by the same general practitioner, following standardised clinical routines for ulcer assessment.

The study group was consecutively included and rather limited in size (n=100).

The difficulty of obtaining follow-up data in a timely fashion from national quality registries could have influenced our results on healing time.

Introduction

A hard-to-heal (or chronic) ulcer is defined as a break in the skin which has not healed within 4–6 weeks.1–4 This definition is independent of the wound type and aetiology.5 Examples of hard-to-heal ulcers are venous, arterial or venous–arterial leg ulcers; diabetic foot ulcers; pressure ulcers; burns6 and ulcers due to trauma, rheumatoid arthritis and malignancy.3 Patients with these ulcers have long been considered neglected, as treatment is often given without diagnosis, thus prolonging ulcer healing time.7 The majority of these patients are elderly and suffer from other conditions such as diabetes and heart and lung diseases.1 8 In addition to these comorbidities, these patients may experience extreme pain.9 10 Treatment is carried out by different caregivers within different medical specialties, and so a multidisciplinary team of professionals is often necessary to establish the ulcer aetiology and provide the proper diagnosis.11

In Sweden, the majority of patients with hard-to-heal ulcers are treated in primary care.7 12 Dedicated wound healing centres in primary care are scarce, but Sweden does have a handful of such centres, including Blekinge Wound Healing Centre (BWHC), providing patient-centred care with a holistic approach. BWHC covers the whole of Blekinge county (150 000 inhabitants). It is divided into two healthcare centres within the same clinical establishment, BWHC West and BWHC East, which are comparably organised in terms of patient population and staff, and with equal resource allocation. Both centres have the same expenditure of time for doctors’ consultations and nurses’ dressing changes, capacity for patient assessment and treatment, and facilities in terms of treatment rooms, dressing materials and computer services.

At BWHC, patients are treated according to a structured wound management based on a Swedish national quality registry, the Registry of Ulcer Treatment (RUT).12 The clinical routines provided by BWHC are the same as those provided by all the other units which register their patients in RUT, and so data from these other units are comparable with data from BWHC.

The Swedish RUT

RUT is a web-based tool for clinical assessment of hard-to-heal ulcers, treatment strategies and continuity of care. Solid clinical research data based on RUT has shown improved quality of life as well as reduction of healing time, treatment costs and antibiotic treatment.7 13 14 There were more than 7000 registrations in RUT in 2016, giving a coverage rate of approximately 25% of all patients with hard-to-heal ulcers in Sweden.

Patients are registered by a nurse or physician on two occasions. The first registration includes variables for assessment of ulcer diagnosis and treatment strategies, while the second includes data on ulcer healing or negative clinical events such as amputation or death. Each patient with a non-healing ulcer remains in the registry until the follow-up is completed.

Telemedicine for wound management

Telemedicine is the use of information technology and electronic communication to allow healthcare professionals to evaluate, diagnose and treat patients at a distance. It typically includes various forms of video consultation or digital transmission of medical imaging and other clinical data.

Transmission of digital photographs has been used within ulcer care in Denmark since 2005, resulting in the reduction of waiting time, ulcer healing time and transportation, the latter of which can often be uncomfortable or painful for the patient.15 Another example is a telemedicine wound care model, which has produced reductions in both hospital admissions and patient transportations.16 The use of three-dimensional images has shown high concordance with inperson consultation for assessment and measurement of wounds.17

Video communication is widely used within different medical specialties today, though thorough documentation and evaluation is insufficient.18 However, there is a lack of use of this technology for ulcer care, even though its focus on the visual is considered ideal for wound management.19 Video communication could be a useful tool, especially in primary care, where there is a need for national guidelines8 as well as dedicated doctors and nurses for wound management.

The aim of this study was to compare video consultation with inperson assessment for patients with hard-to-heal ulcers, in terms of healing time and waiting time.

Methods

Study population and variables

The first study was an analysis of healing time for patients diagnosed through video consultation at BWHC West (study group) compared with patients diagnosed through inperson assessment based on data from RUT (control group) (table 1).

Table 1.

Study population and setting

| Healing time study | Waiting time study | |||

| Participants | Study group (n=100) | Control group (n=1888) | Study group (n=100) | Patients at BWHC East (n=100) |

| Assessment | Video consultation | Inperson assessment | Video consultation | Inperson assessment |

| Setting | Patients at BWHC West | Patients from RUT | Patients at BWHC West | Patients at BWHC East |

| Inclusion | Consecutively included | All patients registered in RUT during the study period | Consecutively included | Consecutively included |

| Inclusion criteria | Age >18; women and men; ulcers of any aetiology, severity, size and duration | |||

| Exclusion criteria | Age <18 Patients with dementia |

Age <18* | Age <18 Patients with dementia |

Age <18* |

| Study period | 1 October 2014 to 30 September 2016 | |||

| Consent | Written consent mandatory | Oral consent according to Swedish registries | Written consent mandatory | Oral consent according to Swedish registries |

*Patients in the control group (the registry) were included regardless of dementia status, since dementia is not recorded in the registry.

BWHC, Blekinge Wound Healing Centre; RUT, Registry of Ulcer Treatment.

The second study was a supplementary analysis of the waiting time for a doctor’s consultation for patients diagnosed through video consultation at BWHC West (study group) compared with patients diagnosed through inperson assessment at a comparable clinic (BWHC East) (table 1). The reason this supplementary analysis was needed is that waiting time is not recorded in RUT.

Our study included ulcers of any aetiology, severity, size and duration. It is possible to register ulcers in RUT from the day they occur (day 0) if patients or staff believe that there will be a prolonged total healing time. The number of patients in the study group was chosen according to the expected number of new undiagnosed patients seeking treatment at BWHC West and BWHC East, respectively, over 2 years.

Every patient in the study group (n=100) gave their written consent. Every patient in the control group (n=1888) gave their oral consent consistent with the principles of Swedish national quality registries.

The healing time study

Study group

The patients were initially assessed during a nurse visit, with measurements taken according to RUT.12 Ulcer size was measured by a planimeter. During this visit, the patient received an iPad programmed with Skype for the upcoming video consultation between the general practitioner (GP) at BWHC and the patient accompanied by the assigned nurse. All iPads had mobile internet access to avoid any need to use the patients’ home Wi-Fi. The iPads had a one-time cost of 325 GBP (US$439) per unit; the software (Skype) was free, and there was a negligible cost for internet access.

Each video consultation took place in the patient’s home or in the primary healthcare centre. During this consultation, the doctor established the ulcer diagnosis and an appropriate treatment strategy which could be carried out by the assigned nurse under supervision. The patient and the treatment strategy were followed up according to general clinical routines. Documentation of the video consultation was transferred to the patient’s medical record.

All patients were included and followed during the study period (1 October 2014 to 30 September 2016). Patients with ulcers that healed had different follow-up times, depending on the date of ulcer healing, which was documented. Patients with ulcers that did not heal were followed to the end of the study period. If amputation or death occurred during the study period, the date of this event was registered and the patient was not followed further. Healing was confirmed clinically by a nurse or a doctor.

Control group

All patients were diagnosed by inperson consultation and registered in RUT. The same measurements were used in both the control group and the study group, except for measurement of ulcer size. For patients in the control group, this was done either by a planimeter or as length multiplied by width, according to different clinical routines.

As with the study group, each patient was included and followed during the study period (1 October 2014 to 30 September 2016). Again, patients with ulcers that healed had different follow-up times, depending on the date of ulcer healing, which was registered in RUT. Patients with ulcers that did not heal were followed to the end of the study period. If amputation or death occurred during the study period, the date of this event was registered and the patient was not followed further. Healing was confirmed clinically by a nurse or a doctor at follow-up registration.

The waiting time study

In Sweden, waiting time is considered clinically important as an indicator of cost-effective healthcare. Age, gender, ulcer size and ulcer duration were not considered to affect the waiting time for a doctor’s consultation, and so were not analysed in this study.

Study group

The same study group was used as for the healing time study.

Patients at BWHC East

All patients with hard-to-heal ulcers were diagnosed by inperson assessment at BWHC East. These patients were likewise assessed according to RUT and followed to ulcer healing or to the end of the study period, whichever occurred first.

Variables

Age (years), gender, ulcer size (cm2), ulcer aetiology and diabetes (yes or no) were analysed in both the study group and the control group. Ulcer size was measured by planimeter (Visitrak; Smith & Nephew Medical, Hull, UK) or by length multiplied by width, according to the established routines in different registration units. Ulcers were categorised by diagnosis: venous ulcers, arterial ulcers, venous–arterial ulcers, pressure ulcers, neuropathic ulcers (diabetic foot ulcers), traumatic ulcers, malignant ulcers, ulcers due to inflammatory vessel diseases such as vasculitis and other ulcers.

Ulcer duration (in days) was defined as the period from when the ulcer occurred to the date of diagnosis by a doctor.

Ulcer healing time (in days) was defined as the interval between the consultation with a doctor and complete ulcer healing. A healed ulcer was defined as an ulcer covered by epithelial regeneration, beneath which there may be scarring and absence of glands or appendages.20

Waiting time (in days) was defined as the interval between referral and consultation with a doctor at the BWHC.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V. 24.0. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean values, SD and ranges, and compared using Student’s t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were expressed as median values and ranges, and differences in groups were analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared between groups using Pearson’s χ2 test. Healing time was analysed with Kaplan-Meier curves. A log-rank test was used for equality of survivor function. A Cox regression analysis was used to explore the effect of age, gender, diabetes, ulcer size and ulcer duration on ulcer healing time. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Patient demographics

Basic data on the study group and the control group are presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Patient demographics: the healing time study

| Study group (n=100) |

Control group (n=1888) | P value | |

| Age, mean (SD, range)* | 77 years (13, 37–98) | 75 years (14, 23–104) | 0.231 |

| Female† | 54% | 56% | 0.744 |

| Diabetes† | 27% | 28% | 0.798 |

| Ulcer size, median (range)‡ | 3.4 cm2 (0.1– 131.6) | 3.8 cm2

(0.01–1196.0) |

0.192 |

| Ulcer duration, median (range)‡ | 124 days (7–3657) | 84 days (0–5839) | 0.001 |

| Healing time, median (95% CI)§ | 59 days (40 to 78) | 82 days (75 to 89) | <0.001 |

Statistically significant P values (<0.05) are marked in bold.

*Student’s t-test.

†χ2 test.

‡Mann-Whitney U-test.

§Log-rank test.

The study group had a mean age of 77 years, the median ulcer size was 3.4 cm2 and the median ulcer duration was 124 days. The control group had a mean age of 75 years, the median ulcer size was 3.8 cm2 and the median ulcer duration was 84 days. In the study group, 13% of the patients were registered as smokers, compared with 14% in the control group.

There was no significant difference in age, gender, ulcer size or diabetes between the patients in the study group and the patients in the control group (table 2).

In both the study group and the control group, 71% (70.8% and 71.3%, respectively) of the ulcers were smaller than 10 cm2 and the remaining 29% (29.2% and 28.7%, respectively) were larger than 10 cm2. The Mann-Whitney U test showed no significant difference in ulcer size between the study group and the control group when analysing only the small ulcers (P=0.053) or only the larger ulcers (P=0.132).

There was a significant difference in ulcer duration between the study group and the control group (P=0.001), with the shortest ulcer duration seen in the control group (table 2).

The aetiology of the ulcers is presented in table 3. A χ2 test was performed concerning the difference in ulcer aetiology between the groups, but the analysis showed that the groups were too small for a comparison.

Table 3.

Ulcer aetiology (%)

| Study group (n=100) | Control group (n=1888) | |

| Venous ulcer | 37 | 35 |

| Arterial ulcer | 19 | 8 |

| Venous–arterial ulcer | 8 | 5 |

| Pressure ulcer | 16 | 14 |

| Neuropathic ulcer | 6 | 4 |

| Traumatic ulcer | 11 | 14 |

| Malignant ulcer | 1 | 1 |

| Inflammatory vessel disease | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 2 | 9 |

| Missing | 0 | 9 |

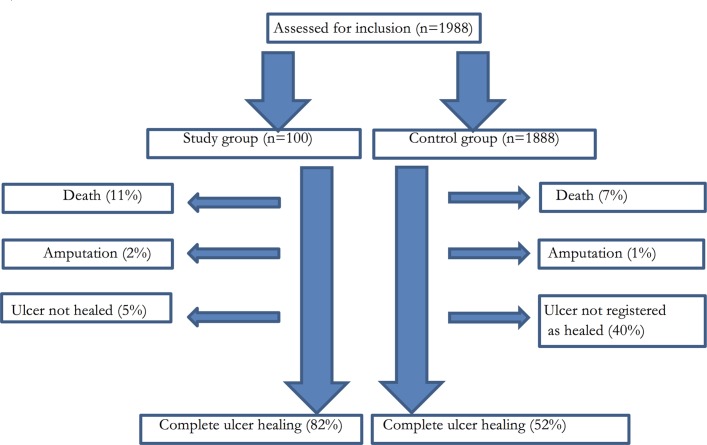

Healing time

The flow chart in figure 1 illustrates the outcome for the participants in the healing time study. Healing rate was 82% (n=82) in the study group and 52% (n=978) in the control group. In the study group, 74% of the patients were followed for <6 months, 8% for 6–12 months and 18% for >12 months. In the control group, 38% of the patients were followed for <6 months, 8% for 6–12 months and 54% for >12 months.

Figure 1.

Flow of participants through the trial.

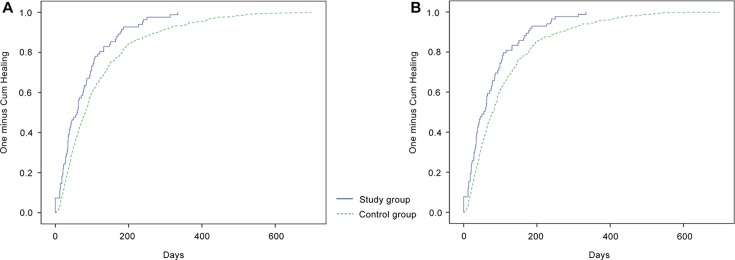

After censorship of unhealed ulcers, deaths and amputations, the median healing time was 59 days (mean: 78 days; 95% CI 40 to 78) in the study group and 82 days (mean: 118 days; 95% CI 75 to 89) in the control group (P<0.001; table 2). Cox regression analysis showed that there was no significant influence of age, gender, ulcer size, diabetes or ulcer duration on healing time.

Healing time is illustrated in figure 2A,B using Kaplan-Meier analysis. Figure 2A is unadjusted for age, gender, diabetes, ulcer size and ulcer duration, while figure 2B is adjusted for age, gender, diabetes, ulcer size and ulcer duration. Both figures are censored for unhealed ulcers, deaths and amputations.

Figure 2.

(A) Ulcer healing time for the study group compared with the control group, unadjusted for age, gender, diabetes, ulcer size and ulcer duration. (B) Ulcer healing time for the study group compared with the control group, adjusted for age, gender, diabetes, ulcer size and ulcer duration. Both figures are censored for unhealed ulcers, deaths and amputations.

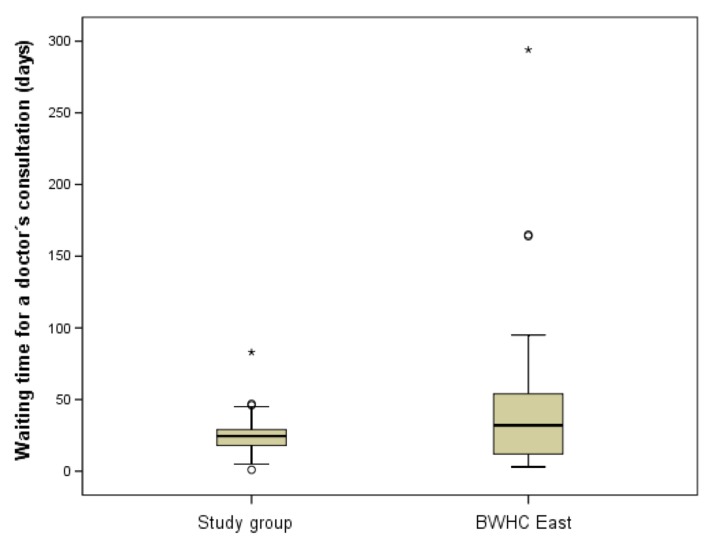

Waiting time

The median waiting time was 25 days (mean: 25 days; range: 1–83 days) in the study group and 32 days (mean: 43 days; range: 3–294 days) for the patients at BWHC East. There was a significant difference in waiting time between the groups (P=0.017), with the shortest waiting time seen in the study group (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Waiting time for a doctor’s consultation for patients in the study group compared with patients at Blekinge Wound Healing Centre (BWHC) East. Extreme outliers are marked with an asterisk (*). Mild outliers are marked with a circle (O).

Discussion

The main finding in this study was the significantly reduced ulcer healing time for patients with hard-to-heal ulcers diagnosed by video consultation (59 days) compared with patients diagnosed by inperson assessment (82 days). We also found that the waiting time was significantly reduced for patients diagnosed by video consultation (25 days) compared with patients diagnosed by inperson consultation (32 days). This study focused on ulcer healing time, as earlier research has shown that reduced ulcer healing time results in lower treatment costs and less time spent on transportation.13–15

In the study group, the ulcer duration before diagnosis was 124 days and healing time was 59 days, while the corresponding figures in the control group were 84 days and 82 days, respectively. One explanation for this could be that the patients in the study group lived in remote and mostly rural areas, and could not easily reach the healthcare centre for assessment of the ulcer. The video consultation made it possible to reach these patients who might have been undiagnosed and without adequate treatment for a long time. Nevertheless, a reduced ulcer healing time was found in the study group, despite the longer ulcer duration, which could demonstrate the importance of a short waiting time.

In clinical practice in Sweden, the main technique for measuring ulcer size is multiplication of length by width, while in specialised clinics such as BWHC, staff use digital planimetry to measure ulcer size. The use of these different measurement techniques is one limitation of this study, but earlier researchers21 have noted that the two methods have a high degree of agreement with each other for ulcers with an area of up to approximately 10 cm2. In this study, most patients (71%) had an ulcer area smaller than 10 cm2, and we found no significant difference in ulcer size in the proportion of smaller ulcers between the study group and the control group. We therefore consider that the use of the two different techniques for measuring ulcer size could be justifiable in this setting, although it remains a weakness. The remaining 29% of the ulcers were larger than 10 cm2, but even for these larger ulcers we found no significant difference in ulcer size between the study group and the control group.

The healthcare system has a strong economic incentive to reduce patients’ waiting time. In the industrialised world, costs for wound management consume about 2%–4% of the annual expenditure on healthcare, and these costs will rise in the future because of longer life expectancy and a larger proportion of patients with diabetes.8 A recent study14 found that staff costs accounted for 87% of the total costs for wound management. Reduced waiting and healing times are thereby strongly related to reduced costs. The present study cannot show whether a 1-week reduction in waiting time could lead to reduced costs, and so further studies are needed to evaluate the cost-effectiveness implications. We did not analyse the number of nurse visits before and after the video consultation, but there were no changes in the clinical routines and so we can assume that the frequencies of dressing changes were not altered. The doctor’s video consultation took place together with the assigned nurse during a regular dressing change, which means no additional costs in nurse time.

Previous studies have shown that telemedicine using digital images provides rapid diagnosis and ulcer care due to reduced waiting time.15 22 We found that this is also true for real-time video consultation, which has not previously been studied thoroughly. Video consultation in this setting seems to be an effective tool to shorten waiting time. One perspective might be the more efficient use of the treatment room. As the doctor does not need any facilities other than a tablet and internet access to carry out the video consultation, the treatment room is freed up for other patients to undergo dressing changes at the same time, thus increasing the number of patients diagnosed and treated per day. The lack of requirement for specialist equipment also means that the doctor is independent of any specific healthcare centre, which may lead to increased doctor availability.

The healing rate in the study group was 82%, compared with 52% in the control group. The figure of 82% is in line with earlier reports of a healing rate of 81% in 24 weeks23 and 83% in 30 weeks.24 The lower healing rate in the registry (ie, in the control group) could be explained by a possible delay in follow-up data being added to the registry. The difficulty of obtaining follow-up data in a timely fashion is a well-known phenomenon for most Swedish quality registries, even though follow-up registration is mandatory and reminders are sent to the registering units. Another limitation of register-based studies is that there is no assurance, other than trust, that a lack of healing date in the registry means that the ulcer has not healed.

Video consultation could be more accessible and suitable for patients with hard-to-heal ulcers who are unable to attend clinical visits due to other medical conditions, pain, disability or reduced mobility,9 10 16 as well as being an alternative for patients who are abroad. Our results indicate that video consultation can effectively transmit sufficient ulcer data to allow a remote specialist in wound care to establish diagnosis and an ideal treatment strategy. This is in line with an earlier study25 of diabetic foot ulcers, which showed no prolonged healing time when comparing telemedical assessment with inperson clinic visits. Concordance of the telemedicine consultation with inperson assessment was also found when a three-dimensional camera was used in a study of diabetic foot ulcers.17 Video consultation provides a useful communication tool, allowing the specialist wound team to support and educate the assigned nurses in primary care and community care in an easy and secure manner. This could be compared with an earlier study26 which showed that telemedicine could effectively transmit sufficient wound data to allow a remote specialist in wound care to provide support to local health professionals working in nursing homes. Telemedicine has also been shown to be a useful communication tool in a home care setting.16 27 The modern technique of video communication through iPad or smartphone is easy to use, and is now widely available in both rural and urban societies.

RUT covers wound management in primary care, community care, private care and in-patient hospital care throughout Sweden, and provides a validated tool for diagnosis and follow-up, meaning that the dataset is large and reliable. One challenge for GPs and nurses in primary care in Sweden is to provide adequate diagnosis and treatment to each patient with a hard-to-heal ulcer in this unselected patient group. RUT was developed in order to deal with this issue, and hence includes hard-to-heal ulcers of any aetiology even when there are different healing trajectories. An earlier study found that departments which registered their patients in RUT reported reduced ulcer healing times after the introduction of the registry.7 Patients not registered in RUT thus probably have a longer ulcer healing time. If the results from our study were to be compared with unregistered patients, the difference in healing time would be even more marked, making our findings somewhat understated.

The GP in charge of the BWHC (HLW) is the first author of this study, which could be considered a bias and a possible explanation for the lower dropout frequency in the study group. However, it could be considered a strength that all patients diagnosed through video consultation were assessed by the same GP following standardised clinical routines for ulcer assessment. The lack of blinded outcome assessment is one limitation, but a register-based study gives the opportunity to analyse large study populations, which is hard to accomplish with blinded outcome studies. Another limitation is the exclusion of patients with dementia in the study group, which was done as recommended by the Ethical Review Board. We cannot exclude the possibility that there were systematic differences between the study group and the control group concerning patients with dementia and organisation of the clinics involved. There is a need for future studies which focus on patient and staff perceptions of the new technology, specific patient groups including patients with dementia, the patient’s quality of life and cost savings for the healthcare system. Further well-designed randomised controlled studies are necessary to understand how best to deploy telemedicine services in ulcer treatment.

The use of a large, representative sample of patients with hard-to-heal ulcers means that the results of the study are generalisable, but the organisation of healthcare systems in different countries may have an impact. Video consultation in this setting can be applied worldwide within all kinds of healthcare systems, and offers an opportunity for improvement in ulcer treatment.

In Sweden, RUT stands for a structured wound management and a way to document the wound healing process. Video consultation is one complementary communication tool, which together with RUT allows an easy ulcer assessment, especially for patients who are unable to attend clinical visits due to severe medical conditions, pain, disability or reduced mobility. Video consultation in parallel with the clinical practice in RUT seems to lead to a more efficient use of resources when reducing healing time and waiting time for this neglected patient group.

Conclusion

The findings from this study illustrate the possible impact of video consultation with a doctor for patients with hard-to-heal ulcers, resulting in significantly reduced healing time and waiting time. Using video consultation as a complement to inperson assessment has the potential to improve ulcer diagnosis, treatment and healing.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HLW led the research project and played the main role in the research design and initial manuscript. RFÖ contributed to the research design and provided knowledge of the Registry of Ulcer Treatment. UJ contributed to the data analysis and interpretation of results. PJM, CF and PA contributed to the research design. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by Scientific Committee of Blekinge County Council’s Research and Development Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Detail has been removed from these case descriptions to ensure anonymity. The editors and reviewers have seen the detailed information available and are satisfied that the information backs up the case the authors are making.

Ethics approval: Regional Ethical Review Board of Lund, Sweden (ref: 2014/228).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Nelzén O, Bergqvist D, Lindhagen A, et al. Chronic leg ulcers: an underestimated problem in primary health care among elderly patients. J Epidemiol Community Health 1991;45:184–7. 10.1136/jech.45.3.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke-Moloney M, Lyons GM, Burke PE, et al. A review of technological approaches to venous ulceration. Crit Rev Biomed Eng 2005;33:511–56. 10.1615/CritRevBiomedEng.v33.i6.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moffatt CJ, Franks PJ, Doherty DC, et al. Prevalence of leg ulceration in a London population. QJM 2004;97:431–7. 10.1093/qjmed/hch075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harding K, Aldons P, Edwards H, et al. Effectiveness of an acellular synthetic matrix in the treatment of hard-to-heal leg ulcers. Int Wound J 2014;11:129–37. 10.1111/iwj.12115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vowden P. Wounds International. Hard-to-heal wounds Made easy. 2011;2 http://www.woundsinternational.com [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chadwick P, Acton C. The use of amelogenin protein in the treatment of hard-to-heal wounds. Br J Nurs 2009;8:18S22–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oien RF, Forssell HW. Ulcer healing time and antibiotic treatment before and after the introduction of the Registry of Ulcer Treatment: an improvement project in a national quality registry in Sweden. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003091 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment (SBU). Chronic ulcers in the elderly – prevention and treatment. Stockholm: Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment, 2014. SBU Report No. 226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akesson N, Oien RF, Forssell H, et al. Ulcer pain in patients with venous leg ulcers related to antibiotic treatment and compression therapy. Br J Community Nurs 2014;19:S6–S13. 10.12968/bjcn.2014.19.Sup9.S6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hellström A, Nilsson C, Nilsson A, et al. Leg ulcers in older people: a national study addressing variation in diagnosis, pain and sleep disturbance. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:25 10.1186/s12877-016-0198-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mooij MC, Huisman LC. Chronic leg ulcer: does a patient always get a correct diagnosis and adequate treatment? Phlebology 2016;31:68–73. 10.1177/0268355516632436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The homepage of the Registry of Ulcer Treatment (RUT). Uppsala Clinical Research Center (UCR), Sweden. www.rut-europe.eu

- 13.Oien RF, Ragnarson Tennvall G. Accurate diagnosis and effective treatment of leg ulcers reduce prevalence, care time and costs. J Wound Care 2006;15:259–62. 10.12968/jowc.2006.15.6.26922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Öien RF, Forssell H, Ragnarson Tennvall G. Cost consequences due to reduced ulcer healing times - analyses based on the Swedish Registry of Ulcer Treatment. Int Wound J 2016;13:957–62. 10.1111/iwj.12465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jelnes R. Telemedicine in the management of patients with chronic wounds. J Wound Care 2011;20:187–90. 10.12968/jowc.2011.20.4.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sood A, Granick MS, Trial C, et al. The Role of Telemedicine in Wound Care: a review and analysis of a database of 5,795 patients from a Mobile Wound-Healing Center in Languedoc-Roussillon, France. Plast Reconstr Surg 2016;138:248S–56. 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowling FL, King L, Paterson JA, et al. Remote assessment of diabetic foot ulcers using a novel wound imaging system. Wound Repair Regen 2011;19:25–30. 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2010.00645.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nordheim LV, Haavind MT, Iversen MM. Effect of telemedicine follow-up care of leg and foot ulcers: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2014;14:565 10.1186/s12913-014-0565-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chittoria RK. Telemedicine for wound management. Indian J Plast Surg 2012;45:412–7. 10.4103/0970-0358.101330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medical Dictionary. Farlex partner medical dictionary. 2012. http://medical-dictionary.thegreedictionary.com/healed+ulcer (Retrieved 26 Sep 2017).

- 21.Oien RF, Håkansson A, Hansen BU, et al. Measuring the size of ulcers by planimetry: a useful method in the clinical setting. J Wound Care 2002;11:165–8. 10.12968/jowc.2002.11.5.26399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chanussot-Deprez C, Contreras-Ruiz J. Telemedicine in wound care. Int Wound J 2008;5:651–4. 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2008.00478.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moffatt CJ, Franks PJ, Oldroyd M, et al. Community clinics for leg ulcers and impact on healing. BMJ 1992;305:1389–92. 10.1136/bmj.305.6866.1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rybak Z, Franks PJ, Krasowski G, et al. Strategy for the treatment of chronic leg wounds: a new model in Poland. Int Angiol 2012;31:550–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasmussen BS, Froekjaer J, Bjerregaard MR, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing telemedical and standard outpatient monitoring of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care 2015;38:1723–9. 10.2337/dc15-0332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vowden K, Vowden P. A pilot study on the potential of remote support to enhance wound care for nursing-home patients. J Wound Care 2013;22:481–8. 10.12968/jowc.2013.22.9.481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Terry M, Halstead LS, O’Hare P, et al. Feasibility study of home care wound management using telemedicine. Adv Skin Wound Care 2009;22:358–64. 10.1097/01.ASW.0000358638.38161.6b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.