Abstract

The double stranded DNA molecule undergoes drastic structural changes during biological processes such as transcription during which it opens locally under the action of RNA polymerases. Local spontaneous denaturation could contribute to this mechanism by promoting it. Supporting this idea, different biophysical studies have found an unexpected increase in the flexibility of DNA molecules with various sequences as a function of the temperature, which would be consistent with the formation of a growing number of locally denatured sequences. Here, we take advantage of our capacity to detect subtle changes occurring on DNA by using high throughput tethered particle motion to question the existence of bubbles in double stranded DNA under physiological salt conditions through their conformational impact on DNA molecules ranging from several hundreds to thousands of base pairs. Our results strikingly differ from previously published ones, as we do not detect any unexpected change in DNA flexibility below melting temperature. Instead, we measure a bending modulus that remains stable with temperature as expected for intact double stranded DNA.

INTRODUCTION

The large amount of accessible DNA conformations stems from the thermal fluctuations of the polymer characterized notably by a defined bending modulus  . DNA fluctuates along the longitudinal axis of its helix over a typical length called the persistence length that decreases with temperature according to

. DNA fluctuates along the longitudinal axis of its helix over a typical length called the persistence length that decreases with temperature according to  at physiological salt conditions, in which DNA charges are almost completely screened as revealed by the plateau reached by

at physiological salt conditions, in which DNA charges are almost completely screened as revealed by the plateau reached by  (1). Assuming that

(1). Assuming that  for double stranded DNA (dsDNA) at 25°C (2), it is expected

for double stranded DNA (dsDNA) at 25°C (2), it is expected  . As long as the DNA keeps intact its double stranded structure,

. As long as the DNA keeps intact its double stranded structure,  varies as the inverse of temperature, assuming that

varies as the inverse of temperature, assuming that  depends only weakly on

depends only weakly on  (3). Under spontaneous thermal fluctuations, DNA base pairs may break to give rise to transient opening of the dsDNA. This local conversion of a few bp of dsDNA into two single stranded DNA (ssDNA) corresponds to the formation of the so-called DNA bubbles, which are ∼25 times more flexible than dsDNA (4,5).

(3). Under spontaneous thermal fluctuations, DNA base pairs may break to give rise to transient opening of the dsDNA. This local conversion of a few bp of dsDNA into two single stranded DNA (ssDNA) corresponds to the formation of the so-called DNA bubbles, which are ∼25 times more flexible than dsDNA (4,5).

The double stranded DNA molecule also undergoes drastic structural changes during biological processes such as transcription during which it opens locally under the action of RNA polymerases. Local spontaneous denaturation could contribute to this mechanism by promoting it (6). DNA loops, which form during the mechanisms of gene expression regulation or recombination, may also be favoured by spontaneous and local opening of the dsDNA enclosed between the two binding sites. The local destabilization of dsDNA was first revealed by hydrogen exchange experiments that showed that a single base pair could spontaneously open at a physiological temperature with a probability lying between 10−7 and 10−5 and depending on the sequence (7). Since then, intensive investigations have been conducted to confirm the existence of DNA bubbles in double stranded DNA molecules. Cyclization assays, carried out either in bulk or at the single molecule level, showed that the probability of encounter of two DNA extremities separated by ∼100 bp was higher than expected for a dsDNA molecule described as an elastic rod with a defined bending modulus (8,9). Similar assays carried out on molecules of ∼200 bp show a decrease with  in the persistence length (

in the persistence length ( ) greater than predicted (10,11). Recently the existence of bubbles in dsDNA under physiological conditions has been questioned through the analysis of the conformation of DNA molecules ranging from several hundreds to thousands bp (11,12).

) greater than predicted (10,11). Recently the existence of bubbles in dsDNA under physiological conditions has been questioned through the analysis of the conformation of DNA molecules ranging from several hundreds to thousands bp (11,12).

Below the melting temperature, the formation probability of DNA bubbles remains theoretically low. Consequently, the change in the DNA structure is expected to be slight and we believed that it was worth revisiting the unsolved issue of the DNA bubbles existence and their possible influence on DNA by taking advantage of our recently proved capacity to detect subtle changes in the DNA conformational dynamics. Exploiting the High Throughput Tethered Particle Motion (HTTPM) techniques (13) in combination with statistical physics modelling, we could retrieve, for instance, the angle of a present local bend (14) or the global persistence length of dsDNA in various salt environments (1). Briefly, HTTPM that we developed a few years ago consists of microcontact printing of arrays of protein spots on glass coverslips and anchoring to these spots DNA molecules by one of their extremities, while the other one is labelled with a hundred-nanometre-sized particle. Several hundreds of these particles, which are nearly free in solution (15), can be observed simultaneously by dark-field microscopy and tracked in real time with nanometric resolution. The measurements of the 2D positions of the DNA-tethered particles enable the calculation of their amplitude of motion as a function of time, which provides access to the conformational state of the DNA molecules in an almost force-free condition. It was shown that although the particle that labels the DNA extremity is much larger than the DNA coil, it affects DNA as a vertical force of only a few tens fN (15).

Accordingly, here, we take advantage of our demonstrated methodology to address the issue of the existence of bubbles in dsDNA under physiological conditions and below their melting temperature through their conformational impact on linear DNA molecules ranging from several hundreds to thousands base pairs. We first show that rising temperature induces a significant decrease in the raw amplitude of motion of the DNA-tethered particle as well as in the relaxation time of the particle. We demonstrate that this latter effect combined to the limited capacities of the detector causes a significant experimental bias in TPM data. After correction, the amplitude of motion of the DNA-tethered particle exhibits only a slight decrease with temperature. Consequently, the DNA persistence length shows a limited decrease with temperature as expected for intact double stranded DNA molecules. Finally, we explore the influence of temperature on the mechanical characteristics of an internal sequence composed of 50 adenines (A50) more prone to denaturation than random sequences (16), and do not detect any temperature effect. Although our results seem at odds with recently published ones at first sight, we could clarify the reasons for these differences and show that our finding leave open the question of a biological impact of temperature on double stranded DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA sample

DNA molecules were produced by PCR amplification (oligonucleotides from Sigma-Aldrich). We used oligos biot-F2000 and dig-R2000 on plasmid pBR322 for DNA molecule denoted by 2000wo, oligos biot-F2000K47 and dig-R2000K47 on plasmid pKH47 (17) for DNA molecule denoted by 2000A, oligos Biot-F2060 and dig-R2060 on plasmid pTOC1 for DNA molecule denoted by 2060, biot-R583 and dig-F583 on plasmid pBR322 for DNA molecule denoted by 583. PCR products were purified as described in (18).

HTTPM experimental procedure

We use a similar HTTPM procedure as published in (13). In brief, coverslips are epoxydized, then micro-contact printed with neutravidin (Invitrogen) to form a square array of isolated spots of about 800 nm size separated by ∼3 μm. The coverslip is assembled with an epoxydized glass slide drilled with four holes and, a silicone spacer that forms two parallel fluidic channels of about 10 μl. The internal surface of the chamber is passivated during 10 min with a PBS buffer (Euromedex) supplemented with pluronic F127 1 mg ml−1 and BSA 0.1 mg ml−1 (Sigma-Aldrich). A 1:1 mix of DNA and 300 nm-sized polystyrene particles (Merck) coated with anti- digoxigenin (Roche) are incubated during 30 min at 37°C and finally injected in the chamber for an overnight incubation. Before the acquisition, the chamber are rinsed with the PBS buffer that has pH 7.0 and an ionic strength of 160 mM, with a pluronic supplementation. For the 583 PEG experiments, the coverslips are pegylated by an overnight silanization of the glass with (3-mercaptopropyl)trimethoxysilane (Sigma-Aldrich) followed by the injection of a 10:1 mix of PEG-maleimide and Biotin-PEG-Maleimide (Sigma-Aldrich) in HEPES 10 mM pH 7. Before the acquisition, the chamber are rinsed with PBS buffer only.

The acquisitions are performed on a dark-field microscope, Zeiss Observer 200 with a x32 objective, equipped with a CMOS camera Hitachi FM200WCL (pixel size = 5.5 μm) and a temperature-controlled stage Physitemp TS-4SMP (±0.1°C temperature precision), enclosed in a home-made environmental chamber. Videos are acquired at 100 Hz with an exposure time  = 10 ms.

= 10 ms.

Each series of measurements is performed according to a systematic procedure described next. Before starting the measurements, the room temperature is set to 20°C for at least 1h then controlled and maintained at 20°C until the end. The chamber containing the sample is immobilized on the stage and the temperature of the stage is set to 15°C for 1h, then the 1 min acquisition is performed. Then, the temperature set point is increased by 5°C. After the temperature of the stage is stabilized, the sample is left in this new thermal condition for 4 min, or 8 min if some buffer was flushed in, then the 1 min acquisition was carried out. This last step is repeated until temperature has reached 75°C. During these series of measurements, we observed that tethered particles broke away from the surface all especially above 45°C which drove us to rinse the chamber with buffer in order to retrieve a clean background and be able to track the particles again. The number of immobilized particles increased with temperature in a similar way.

Tracking of the particles that is based on the centroid calculation gives access to the  and

and  positions of the particles. Then, are calculated the anchoring points of the DNA-tethered particles according to

positions of the particles. Then, are calculated the anchoring points of the DNA-tethered particles according to  and

and  , the instantaneous projected 2D distances of these DNA-tethered particles to their anchoring point defined, the symmetry factors as in (19) and finally the root-mean-square of this distance, denoted by

, the instantaneous projected 2D distances of these DNA-tethered particles to their anchoring point defined, the symmetry factors as in (19) and finally the root-mean-square of this distance, denoted by  , determined over a sliding window of

, determined over a sliding window of  s as

s as  .

.

Data analysis

The DNA-particle complex end-to-end distance  is processed according to the procedure described in detail in (14). In brief, DNA-particle complexes that do not respect the criteria of validity, due in particular to aberrant

is processed according to the procedure described in detail in (14). In brief, DNA-particle complexes that do not respect the criteria of validity, due in particular to aberrant  and out of range symmetry factor (for example induced by an immobilized particle or more than 1 DNA molecule tethered to the same particle), are discarded. Then the relaxation time

and out of range symmetry factor (for example induced by an immobilized particle or more than 1 DNA molecule tethered to the same particle), are discarded. Then the relaxation time  is extracted from the correlation function in

is extracted from the correlation function in  and

and  position calculated along a trajectory at time

position calculated along a trajectory at time  , with N the total number of frames of the traces (19) and,

, with N the total number of frames of the traces (19) and,  the pointing error obtained as the standard deviation of the positions of immobilized particles accumulated during 1 min and found equal to 10 nm:

the pointing error obtained as the standard deviation of the positions of immobilized particles accumulated during 1 min and found equal to 10 nm:

|

|

Fitting the so-obtained experimental correlation function with the following theoretical one

|

One gets the measured relaxation time  , from which one deduces the real relaxation time of the complex as follows:

, from which one deduces the real relaxation time of the complex as follows:

|

We will explain below how the correction from the detector-averaging blurring effect is performed considering  and

and  to obtain

to obtain  . Examples of traces are given in Supplementary Figure S1.

. Examples of traces are given in Supplementary Figure S1.

At last, the experimental value of  of an ensemble of particles is calculated as the mean value of the distribution, and the standard error (se) on

of an ensemble of particles is calculated as the mean value of the distribution, and the standard error (se) on  of an ensemble of particles is obtained by using the bootstrap method of R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

of an ensemble of particles is obtained by using the bootstrap method of R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Decrease in the raw amplitude of motion of the DNA-particle complexes with temperature

DNA bubbles result from the conversion of a segment of the double-stranded helices into two isolated single strands due to the hydrogen bond breaks. Their formation within a dsDNA molecule leads to a local decrease in the rigidity of the DNA molecule. At physiological temperature, the persistence length is expected to decrease from  50 nm for the dsDNA to about 2 nm for two parallel ssDNA, assuming

50 nm for the dsDNA to about 2 nm for two parallel ssDNA, assuming  1 nm for ssDNA (10). To detect DNA bubbles, we used HTTPM and measured the amplitude of motion,

1 nm for ssDNA (10). To detect DNA bubbles, we used HTTPM and measured the amplitude of motion,  , of particles bound to the coverslip through single DNA molecules. This amplitude decreases when

, of particles bound to the coverslip through single DNA molecules. This amplitude decreases when  lowers because the DNA end-to-end distance decreases.

lowers because the DNA end-to-end distance decreases.

We chose two DNA molecules of 2000 bp, one containing a central core composed of a 50 A-tract (2000A) and another deprived of such a central core (2000wo), one DNA of 2060 bp with a different sequence (2060) and a fourth one of only 583 bp (583). Using a Worm Like Chain (WLC) model in which a local flexible insert is incorporated, we can predict the expected results for HTTPM measurements (14). We find that a permanent bubble of only 3 bp located at the center of a torsionally unconstrained linear DNA molecule of ∼0.6 or 2 kb would induce a change of amplitude of motion of about 3 nm in our HTTPM configuration (Supplementary Figure S2). As this change exceeds our HTTPM resolution, typically lower than 2 nm (Supplementary Table S1), we expect to be able to detect such a permanent bubble. If the 3 bp bubble formed transiently only, the change in amplitude of motion might become too small to be detected.

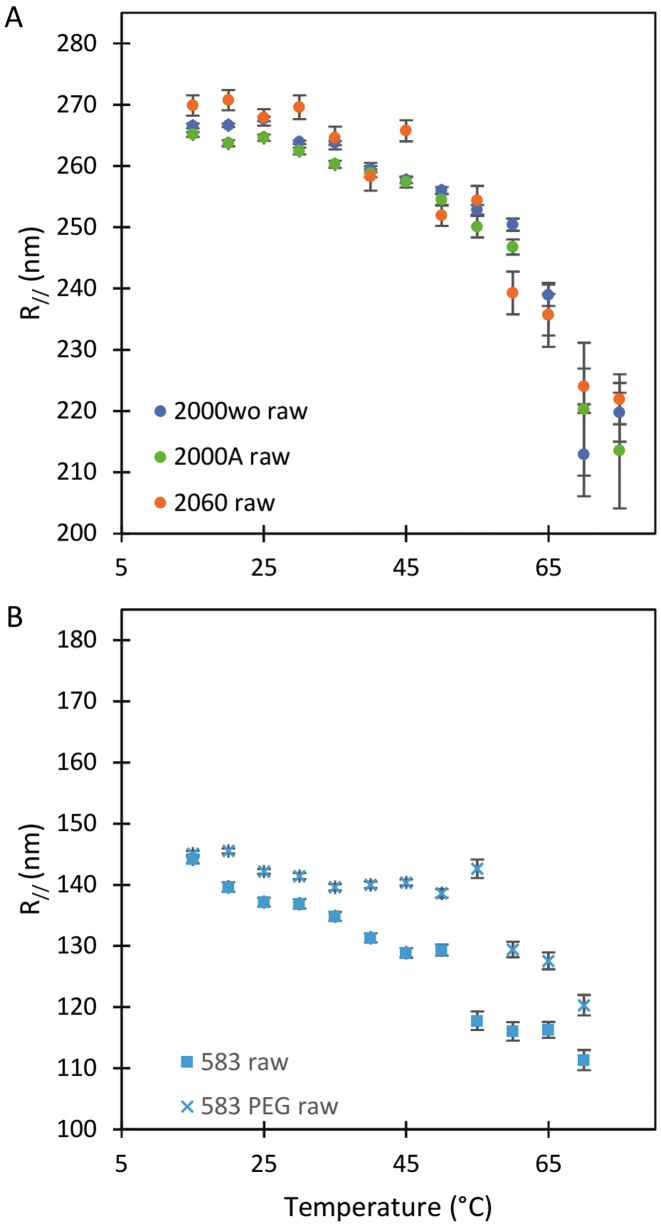

We observe a significant decrease in the raw amplitude of motion as a function of  for these four DNA molecules (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S3), with an even sharper decrease for the shortest molecule. We were puzzled by this last result and tested whether it could stem from the antifouling layer made of copolymers, which is adsorbed on the epoxydized glass surface. The long copolymer, pluronic F127, was replaced by a short one, pluronic L64, with highly reduced hydrophobic and hydrophobic blocks, which was therefore expected to form an anti-fouling layer of reduced density and thickness (20). It resulted in the massive immobilization of the particle at 40°C and the visualization of micelles (Supplementary Figure S4), which gives evidence for a strong temperature destabilization of the copolymer L64 layer adsorbed on the surface. This observation drove us to the conclusion that the anti-fouling properties of the layer formed by the copolymer F127 at the surface of the coverslips may also be degraded as the temperature increases due to a partial desorption of the copolymer from the coverslip. This could induce some sticking events of the DNA-particle complex on the coverslips and participate to the apparent reduction of

for these four DNA molecules (Figure 1 and Supplementary Figure S3), with an even sharper decrease for the shortest molecule. We were puzzled by this last result and tested whether it could stem from the antifouling layer made of copolymers, which is adsorbed on the epoxydized glass surface. The long copolymer, pluronic F127, was replaced by a short one, pluronic L64, with highly reduced hydrophobic and hydrophobic blocks, which was therefore expected to form an anti-fouling layer of reduced density and thickness (20). It resulted in the massive immobilization of the particle at 40°C and the visualization of micelles (Supplementary Figure S4), which gives evidence for a strong temperature destabilization of the copolymer L64 layer adsorbed on the surface. This observation drove us to the conclusion that the anti-fouling properties of the layer formed by the copolymer F127 at the surface of the coverslips may also be degraded as the temperature increases due to a partial desorption of the copolymer from the coverslip. This could induce some sticking events of the DNA-particle complex on the coverslips and participate to the apparent reduction of  . We confirmed this hypothesis by measuring a lower decrease of

. We confirmed this hypothesis by measuring a lower decrease of  when PEG covalently bound to the glass coverslip, and therefore temperature resistant, was employed as a passivating agent (Figure 1B). We considered this passivation issue to be less critical for long DNA molecules as we estimated that the probability for a tethered particle to be close to the surface plane is about 2 times more important for a DNA tether of 0.6 kb than for a 2 kb long DNA (see Supplementary text).

when PEG covalently bound to the glass coverslip, and therefore temperature resistant, was employed as a passivating agent (Figure 1B). We considered this passivation issue to be less critical for long DNA molecules as we estimated that the probability for a tethered particle to be close to the surface plane is about 2 times more important for a DNA tether of 0.6 kb than for a 2 kb long DNA (see Supplementary text).

Figure 1.

Temperature dependence of the measured amplitude of motion  for DNA molecules of (A) 2060 bp (

for DNA molecules of (A) 2060 bp ( ), 2000 bp without A50 tract (

), 2000 bp without A50 tract ( ) and 2000 bp with A50 (

) and 2000 bp with A50 ( )] and of (B) 583 bp on an epoxydized surface passivated by pluronic (

)] and of (B) 583 bp on an epoxydized surface passivated by pluronic ( ) and 583 bp on a PEG surface (

) and 583 bp on a PEG surface ( ). Error bars (95% confidence intervals) are displayed; if not, they are smaller than the symbol size.

). Error bars (95% confidence intervals) are displayed; if not, they are smaller than the symbol size.

Influence of the temperature on the buffer viscosity and the detector-averaging blurring effect

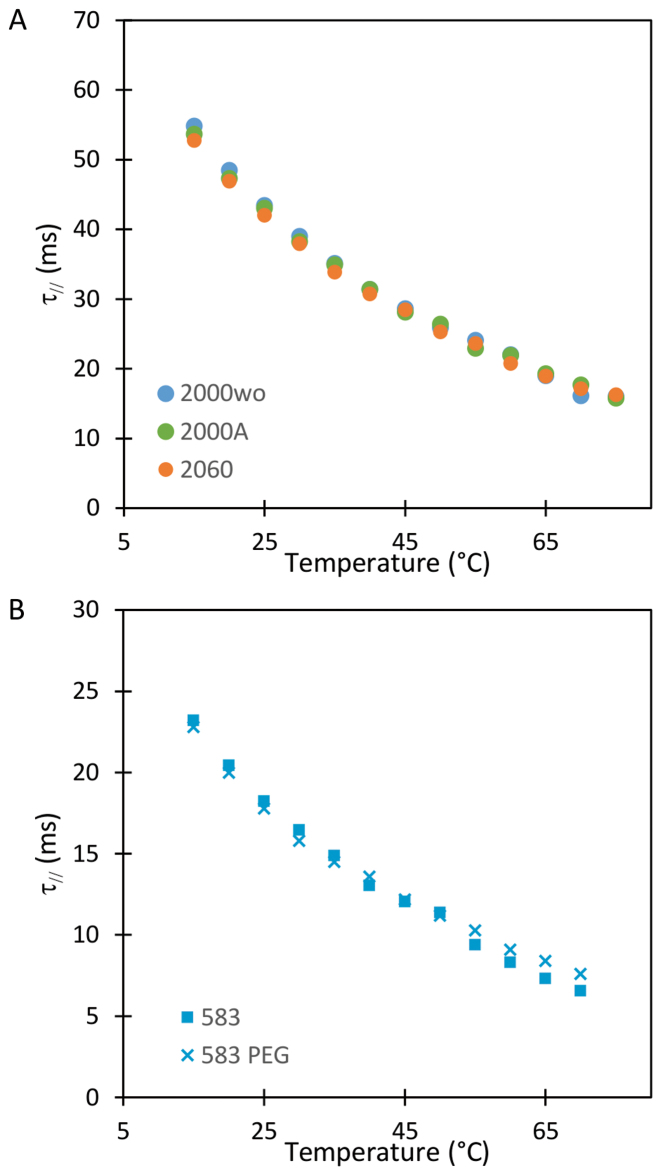

The increase in temperature between 15 to 75°C causes the viscosity of the buffer to decrease by more than one third. Consequently, we expected the relaxation time of DNA-particle complex, denoted by  , to decrease considerably in this temperature range. Experimental results showed a roughly 3-fold smooth reduction in

, to decrease considerably in this temperature range. Experimental results showed a roughly 3-fold smooth reduction in  (Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S5A). In fact,

(Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure S5A). In fact,  is inversely proportional to the diffusion coefficient of the DNA-particle complex which follows the relation

is inversely proportional to the diffusion coefficient of the DNA-particle complex which follows the relation  when neglecting hydrodynamic interactions between the DNA and the tethered particle (21). Assuming that the Rouse or Zimm model describe the diffusion of DNA (22), the diffusion coefficients of particles and DNA should be both proportional to

when neglecting hydrodynamic interactions between the DNA and the tethered particle (21). Assuming that the Rouse or Zimm model describe the diffusion of DNA (22), the diffusion coefficients of particles and DNA should be both proportional to  . As a result,

. As a result,  was expected to remain constant with temperature. We estimated the theoretical value of

was expected to remain constant with temperature. We estimated the theoretical value of  with

with  and by considering that the viscosity of the buffer,

and by considering that the viscosity of the buffer,  , was similar to the water one (23) (Supplementary Figure S5B).

, was similar to the water one (23) (Supplementary Figure S5B).  displays a slight increase of about 15% (Supplementary Figure S5C), which indicates a need to refine further in future works the theoretical description of DNA-tethered particles behaviour.

displays a slight increase of about 15% (Supplementary Figure S5C), which indicates a need to refine further in future works the theoretical description of DNA-tethered particles behaviour.

Figure 2.

Temperature dependence of the relaxation time of particles tethered to the coverslips by DNA molecule of (A) 2060 bp ( ), 2000 bp without A50 tract (

), 2000 bp without A50 tract ( ) and 2000 bp with A50 (

) and 2000 bp with A50 ( ) and of (B) 583 bp on an epoxydized surface passivated by pluronic (

) and of (B) 583 bp on an epoxydized surface passivated by pluronic ( ) and 583 bp on a PEG surface (

) and 583 bp on a PEG surface ( ).

).

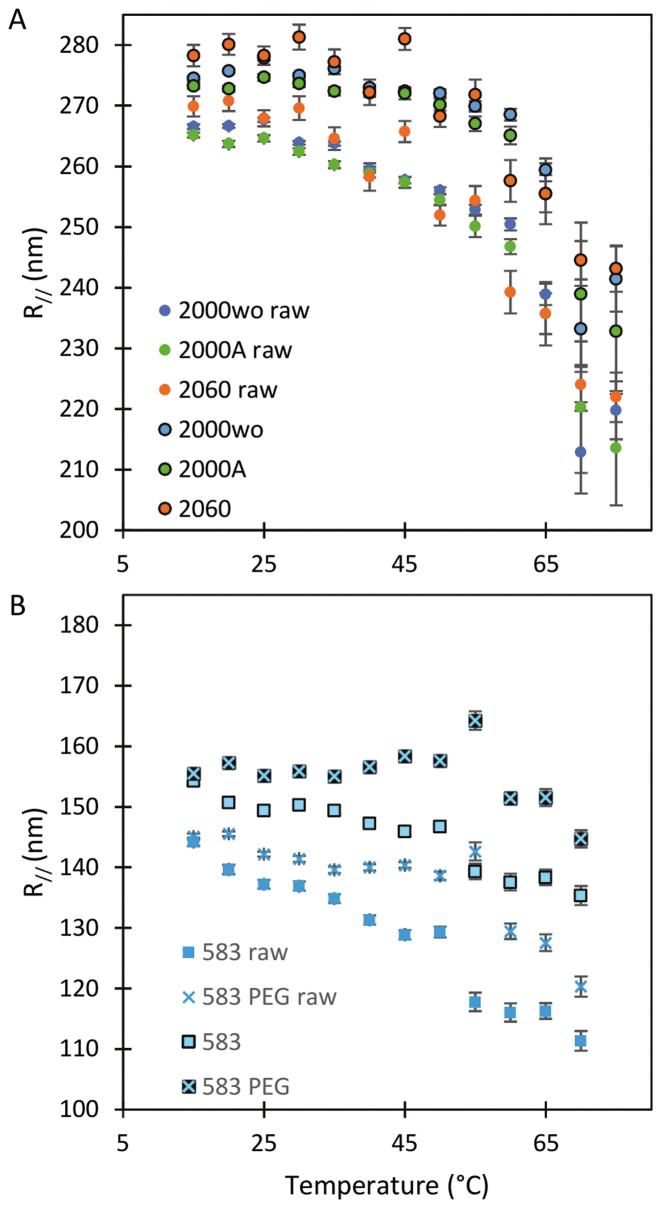

This rapid decrease in  urges us to correct our data from the detection time-averaging blurring. This can be achieved using the equation

urges us to correct our data from the detection time-averaging blurring. This can be achieved using the equation  , with

, with  the exposure time (21). Note that at fixed relaxation time

the exposure time (21). Note that at fixed relaxation time  , if

, if  goes to 0, then expanding the exponential at order 2 in

goes to 0, then expanding the exponential at order 2 in  , one gets that

, one gets that  . This is expected because there is no blurring effect at small

. This is expected because there is no blurring effect at small  . By contrast, if

. By contrast, if  goes to infinity,

goes to infinity,  tends to 0 because averaging the trajectory over a very long period gives the anchoring point coordinates

tends to 0 because averaging the trajectory over a very long period gives the anchoring point coordinates  . Even for our exposure time, as small as

. Even for our exposure time, as small as  , the correction modifies

, the correction modifies  by an increase of up to 10% for the 2 kb DNA and 20% for the 0.6 kb molecule (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S6). The temperature dependence of

by an increase of up to 10% for the 2 kb DNA and 20% for the 0.6 kb molecule (Figure 3 and Supplementary Figure S6). The temperature dependence of  is extremely moderate up to 60°C for the 2 kb DNA molecules as well as the 0.6 kb one measured with PEG as a passivating agent. Above 60°C, a fall in

is extremely moderate up to 60°C for the 2 kb DNA molecules as well as the 0.6 kb one measured with PEG as a passivating agent. Above 60°C, a fall in  is observed for both types of DNA as if new processes were at play in the sample (see discussion below).

is observed for both types of DNA as if new processes were at play in the sample (see discussion below).

Figure 3.

Temperature dependence of  for DNA of (A) 2060 bp (

for DNA of (A) 2060 bp ( ), 2000 bp without A50 tract (

), 2000 bp without A50 tract ( ) and 2000 bp with A50 tract (

) and 2000 bp with A50 tract ( ) before correction for the detector time-averaging blurring and after this correction (black contour line) and (B) of 583 bp on an epoxydized surface passivated by pluronic (

) before correction for the detector time-averaging blurring and after this correction (black contour line) and (B) of 583 bp on an epoxydized surface passivated by pluronic ( ) and 583 bp on a PEG surface (

) and 583 bp on a PEG surface ( ) before correction for the detector time-averaging blurring and after this correction (black contour line). Error bars (95% confidence intervals) are displayed; if not, they are smaller than the symbol size.

) before correction for the detector time-averaging blurring and after this correction (black contour line). Error bars (95% confidence intervals) are displayed; if not, they are smaller than the symbol size.

Decrease in the DNA persistence length with temperature

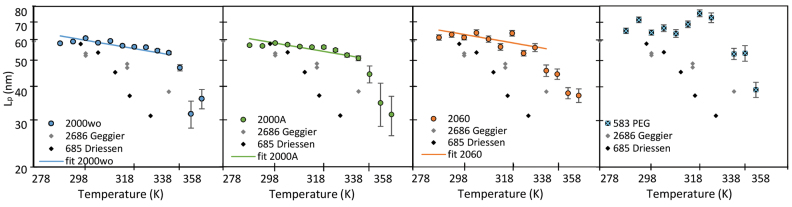

In order to determine the change in rigidity caused by the rise in temperature, we extracted the persistence length (Figure 4) using the calibration curve we obtained by an exact sampling simulation (1) (Supplementary Figure S7). We show that in the physiologically relevant temperature range from 15 to 60°C, namely below the melting temperature  predicted by EMBOSS’DAN (24), the temperature induces a variation of

predicted by EMBOSS’DAN (24), the temperature induces a variation of  similar to the expected one for a structurally conserved double stranded DNA that is

similar to the expected one for a structurally conserved double stranded DNA that is  with

with  assuming

assuming  = 50 nm for dsDNA at 25°C. The three series of data are correctly fitted by this equation with

= 50 nm for dsDNA at 25°C. The three series of data are correctly fitted by this equation with  as a single parameter and such that

as a single parameter and such that  for 2000wo,

for 2000wo,  for 2000A and

for 2000A and  for 2060. The results obtained with the 583 bp long DNA are in qualitative agreement, but too noisy to be well fitted.

for 2060. The results obtained with the 583 bp long DNA are in qualitative agreement, but too noisy to be well fitted.

Figure 4.

Temperature dependence of  for DNA molecule of 2000 bp without A50 tract (

for DNA molecule of 2000 bp without A50 tract ( ) and 2000 bp with A50 (

) and 2000 bp with A50 ( ), 2060 bp (

), 2060 bp ( ), and 583 bp on a PEG surface (

), and 583 bp on a PEG surface ( ), as well as the results obtained by Geggier et al. on a 2686 bp circular DNA, as well as those obtained by Driessen et al. on a 685 bp linear DNA. Fits performed between 15 and 60°C by

), as well as the results obtained by Geggier et al. on a 2686 bp circular DNA, as well as those obtained by Driessen et al. on a 685 bp linear DNA. Fits performed between 15 and 60°C by  with

with  and

and  as a fitting parameter, are shown when possible. Data are represented with logarithmic scales for both axes. Error bars (95% confidence intervals) are displayed, if not, they are smaller than the symbol size.

as a fitting parameter, are shown when possible. Data are represented with logarithmic scales for both axes. Error bars (95% confidence intervals) are displayed, if not, they are smaller than the symbol size.

A closer look to Figure 4 reveals that the persistence length of 2000 bp long DNA lacking an A50 sequence remains at all temperatures slightly above  measured for the almost identical 2000 bp long DNA containing a A50 sequence in the center of the molecule. The only differences between the two DNA molecules result from the presence of the A50 in the center of 2000A and the existence of two new 25 bp long sequences at each extremity of the 2000wo molecule without any sequence specificity able to induce structural peculiarities. This effect could result from the presence of either a more flexible DNA sequence or a local bend in the 2000A construct. Using our ‘local stiffness and kink WLC’ model (14), we extracted the corresponding characteristics, the local persistence length

measured for the almost identical 2000 bp long DNA containing a A50 sequence in the center of the molecule. The only differences between the two DNA molecules result from the presence of the A50 in the center of 2000A and the existence of two new 25 bp long sequences at each extremity of the 2000wo molecule without any sequence specificity able to induce structural peculiarities. This effect could result from the presence of either a more flexible DNA sequence or a local bend in the 2000A construct. Using our ‘local stiffness and kink WLC’ model (14), we extracted the corresponding characteristics, the local persistence length  and the bend angle θA50, from the difference measured between

and the bend angle θA50, from the difference measured between  and

and  , assuming the global persistence length of the 2000A DNA to be equal to the one measured for 2000wo due to sequence similarity. Finally we found that 2000A may contain either a possible flexible insert with

, assuming the global persistence length of the 2000A DNA to be equal to the one measured for 2000wo due to sequence similarity. Finally we found that 2000A may contain either a possible flexible insert with  = 26 ± 10 nm or a bend with an angle θA50 = 39 ± 13° for a temperature ranging from 15 to 60°C. We conclude at this stage on an apparent increased flexibility of the A50 core as compared to random DNA at 20°C or the existence of a bend generated by A50 core (see Discussion below); however, these characteristics do not exhibit any temperature induced trend detectable with HTTPM (Supplementary Figure S8).

= 26 ± 10 nm or a bend with an angle θA50 = 39 ± 13° for a temperature ranging from 15 to 60°C. We conclude at this stage on an apparent increased flexibility of the A50 core as compared to random DNA at 20°C or the existence of a bend generated by A50 core (see Discussion below); however, these characteristics do not exhibit any temperature induced trend detectable with HTTPM (Supplementary Figure S8).

DISCUSSION

In this HTTPM assay, we were able to detect a marked decrease in  as a function of the temperature between 15 and 70°C for particles tethered to the coverslip by various 2 and 0.6 kb long DNA molecules immersed in phosphate-buffered saline. We have shown that, in the subrange of temperature from 15 to 60°C, this decrease can be mainly attributed to the detector time-averaging blurring. This effect depends on the ratio between the exposure time of the detector that remains constant over the temperature range and the relaxation time of DNA-particles, which dramatically decreases as a function of the temperature due to the diminution of the buffer viscosity. We correct the data for this bias and obtain

as a function of the temperature between 15 and 70°C for particles tethered to the coverslip by various 2 and 0.6 kb long DNA molecules immersed in phosphate-buffered saline. We have shown that, in the subrange of temperature from 15 to 60°C, this decrease can be mainly attributed to the detector time-averaging blurring. This effect depends on the ratio between the exposure time of the detector that remains constant over the temperature range and the relaxation time of DNA-particles, which dramatically decreases as a function of the temperature due to the diminution of the buffer viscosity. We correct the data for this bias and obtain  , which shows a reduced decrease as a function of the temperature when compared with

, which shows a reduced decrease as a function of the temperature when compared with  variation. For the long 2 kb DNA, we attributed this reduction of

variation. For the long 2 kb DNA, we attributed this reduction of  to changes in thermal fluctuation amplitude of the DNA molecule. For the short 0.6 kb molecule, we observed that the reduction of

to changes in thermal fluctuation amplitude of the DNA molecule. For the short 0.6 kb molecule, we observed that the reduction of  remained important with temperature and we showed that this was function of the nature of passivating layer. Finally, the persistence length was extracted from

remained important with temperature and we showed that this was function of the nature of passivating layer. Finally, the persistence length was extracted from  and exhibited a decrease with temperature up to 60°C in accordance with DNA behaving as a structurally intact double stranded molecule that keeps constant its bending modulus in agreement with results measured on free DNA in solution (3). Above 60°C,

and exhibited a decrease with temperature up to 60°C in accordance with DNA behaving as a structurally intact double stranded molecule that keeps constant its bending modulus in agreement with results measured on free DNA in solution (3). Above 60°C,  falls due to a complex combination of partial denaturation that is discussed later as well as biochip disassembly. The presence of an A50 sequence in the centre of the molecule caused only a slight difference, which could be explained by the presence of either a flexible hinge or a bend.

falls due to a complex combination of partial denaturation that is discussed later as well as biochip disassembly. The presence of an A50 sequence in the centre of the molecule caused only a slight difference, which could be explained by the presence of either a flexible hinge or a bend.

Poly(dA:dT) regions found in the eukaryotic chromosome are depleted in nucleosomes (25), which have been interpreted as a consequence of an increased rigidity of poly(dA:dT) as compared to random sequences (26). In accordance with this hypothesis, cyclisation assays carried out with single molecule FRET (9) showed a strong decrease in the rate of cyclization for 100 bp long DNA molecules containing A38 instead of a random sequence, which is compatible with a much stiffer A38 sequence. We measured the bend angle of a CA6CGG sequence on a DNA containing this A6-tract assembled in phase, ∼19°, as well as a slight increase in rigidity for A6 on samples containing four CA6CGG assembled out of phase,  (14). Consequently, it is unlikely that A50 constitutes a flexible hinge. The decrease in

(14). Consequently, it is unlikely that A50 constitutes a flexible hinge. The decrease in  that we measure in presence of GA50CTG may instead result from a slight increase in rigidity of the pure A50 itself and the formation of bends, at its boundaries with the rest of the molecule. The complex interplay between the presence of a long rigid segment and bends at its extremities may explain the higher angle value of 39° found for GA50CTG as compared with the 19° we previously measured for CA6CGG tract. It should be noted however that naturally-existing poly(dA:dT)-rich DNA appeared more flexible than random DNA when characterized by the measurement of the probability of looping of DNA by the lac repressor between two sites separated by about 100 bp (27). Further characterization is therefore needed to fully understand the conformations observed for An homopolymers and poly(dA:dT) heteropolymers found in nature.

that we measure in presence of GA50CTG may instead result from a slight increase in rigidity of the pure A50 itself and the formation of bends, at its boundaries with the rest of the molecule. The complex interplay between the presence of a long rigid segment and bends at its extremities may explain the higher angle value of 39° found for GA50CTG as compared with the 19° we previously measured for CA6CGG tract. It should be noted however that naturally-existing poly(dA:dT)-rich DNA appeared more flexible than random DNA when characterized by the measurement of the probability of looping of DNA by the lac repressor between two sites separated by about 100 bp (27). Further characterization is therefore needed to fully understand the conformations observed for An homopolymers and poly(dA:dT) heteropolymers found in nature.

Our results on the temperature dependence of  are at odds with those obtained by Driessen et al. who used a similar TPM assay to study a 0.7 kb DNA molecule in a buffer with a high ionic strength, greater than 100 mM, as it is the case here (12). They indeed found a temperature dependence of

are at odds with those obtained by Driessen et al. who used a similar TPM assay to study a 0.7 kb DNA molecule in a buffer with a high ionic strength, greater than 100 mM, as it is the case here (12). They indeed found a temperature dependence of  stronger than expected for dsDNA with for instance

stronger than expected for dsDNA with for instance  instead of the

instead of the  expected in the case of a structurally intact dsDNA. We believe that one reason for this is that they did not take into account the bias induced by detector time-averaging blurring that results from the decrease in the buffer viscosity with

expected in the case of a structurally intact dsDNA. We believe that one reason for this is that they did not take into account the bias induced by detector time-averaging blurring that results from the decrease in the buffer viscosity with  . We performed the correction on their published data (Supplementary Figure S9) by extrapolating the relaxation time of the DNA-particle complex at 20°C from the dependence of the DNA length and particle size that we predicted theoretically and previously validated experimentally (21). We then assumed in first approximation that

. We performed the correction on their published data (Supplementary Figure S9) by extrapolating the relaxation time of the DNA-particle complex at 20°C from the dependence of the DNA length and particle size that we predicted theoretically and previously validated experimentally (21). We then assumed in first approximation that  remains constant with temperature, which allowed us to get an estimate of

remains constant with temperature, which allowed us to get an estimate of  at all temperatures. The corrected amplitude of motion that was then estimated was found to be reduced by 4 nm at maximum, instead of 15 nm for

at all temperatures. The corrected amplitude of motion that was then estimated was found to be reduced by 4 nm at maximum, instead of 15 nm for  . We finally derived the persistence length using a calibration curve obtained as before but considering the specific sizes of their particle and DNA. We found that

. We finally derived the persistence length using a calibration curve obtained as before but considering the specific sizes of their particle and DNA. We found that  was reduced by 4 nm at maximum for temperature ranging from 23 to 52°C, in accordance with our results. It should be noted that, overall, the values of

was reduced by 4 nm at maximum for temperature ranging from 23 to 52°C, in accordance with our results. It should be noted that, overall, the values of  we extracted from their data drastically differ from those published by the authors. This discrepancy may in part originate from the passivating system. The DNA employed by Driessen et al. is short and therefore more likely to interact with the coverslip surface. Although the possible interactions between the tethered particle and the surface can be judiciously exploited to measure the kinetic of association between a ligand and a receptor (28), the contribution of these interactions between the tethered particle and the surface to the TPM results are usually difficult to evaluate precisely. An efficient passivation of the surface toward unspecific binding of the immobilized DNA-particles remains an issue in TPM as in other techniques using tethered DNA (29). Another major source of discrepancy lies in their use of the Langevin equation, in which the dependence of the diffusion coefficient with the position (30) has been omitted in Driessen at al.’s publication. This omission results in an apparent force that pushes the particles down to the glass surface reducing the theoretically expected amplitude of motion for a given persistence length. It therefore constitutes another reason why Driessen et al. deduced normal persistence length values from their low TPM data values, while we could not.

we extracted from their data drastically differ from those published by the authors. This discrepancy may in part originate from the passivating system. The DNA employed by Driessen et al. is short and therefore more likely to interact with the coverslip surface. Although the possible interactions between the tethered particle and the surface can be judiciously exploited to measure the kinetic of association between a ligand and a receptor (28), the contribution of these interactions between the tethered particle and the surface to the TPM results are usually difficult to evaluate precisely. An efficient passivation of the surface toward unspecific binding of the immobilized DNA-particles remains an issue in TPM as in other techniques using tethered DNA (29). Another major source of discrepancy lies in their use of the Langevin equation, in which the dependence of the diffusion coefficient with the position (30) has been omitted in Driessen at al.’s publication. This omission results in an apparent force that pushes the particles down to the glass surface reducing the theoretically expected amplitude of motion for a given persistence length. It therefore constitutes another reason why Driessen et al. deduced normal persistence length values from their low TPM data values, while we could not.

Similarly, a stronger than expected temperature dependence of  was measured by Geggier et al. (11) as shown in Figure 4; however, they carried out very different experiments studying either the ligation probability of the sticky ends of linear 0.2 kb DNA with cyclization assays or the equilibrium distribution of topoisomers of 3 kb circular DNA molecules. Cyclization assays are probably more efficient than TPM in revealing scarce events such as DNA bubbles or kinks especially since they deal with much shorter DNA molecules, for which any bp difference represents almost 1% change in the sequence. Whether this higher ligation probability arises from transient kinks or bubbles, that is to say a steep bend or a flexible hinge, remains unclear. In any case, the persistence length is a global value that accounts for the flexibility of a DNA molecule averaged over its contour length. For 100 bp molecules, such a global

was measured by Geggier et al. (11) as shown in Figure 4; however, they carried out very different experiments studying either the ligation probability of the sticky ends of linear 0.2 kb DNA with cyclization assays or the equilibrium distribution of topoisomers of 3 kb circular DNA molecules. Cyclization assays are probably more efficient than TPM in revealing scarce events such as DNA bubbles or kinks especially since they deal with much shorter DNA molecules, for which any bp difference represents almost 1% change in the sequence. Whether this higher ligation probability arises from transient kinks or bubbles, that is to say a steep bend or a flexible hinge, remains unclear. In any case, the persistence length is a global value that accounts for the flexibility of a DNA molecule averaged over its contour length. For 100 bp molecules, such a global  is barely appropriate and can hardly be compared to the values that we deduced from the conformations measurements on several hundred bp to several kb. The strong temperature dependence measured on the 3 kb DNA could be explained by the fact that it is derived from the detection of DNA topoisomers including supercoiled ones, for which the helix are subjected to additional, possibly destabilizing, mechanical constrains. As a result,

is barely appropriate and can hardly be compared to the values that we deduced from the conformations measurements on several hundred bp to several kb. The strong temperature dependence measured on the 3 kb DNA could be explained by the fact that it is derived from the detection of DNA topoisomers including supercoiled ones, for which the helix are subjected to additional, possibly destabilizing, mechanical constrains. As a result,  evaluated in these conditions can hardly be directly compared to our data obtained on linear DNA molecules.

evaluated in these conditions can hardly be directly compared to our data obtained on linear DNA molecules.

Our theoretical prediction indicates that TPM would allow the detection of long-lived 3 bp bubbles as long as their flexibility would be accounted for by considering  equal to 2 nm, that is to say twice the persistence length of ssDNA. Using cyclisation assays on 0.1 kb DNA, Forties et al. (10) showed that this short persistence length is reached for a bubble with a length greater than 4 bp. Since in our buffer conditions, the predicted melting temperatures are about 80°C (Supplementary Figure S10), DNA bubbles containing more than 4 bp are very likely to be scarce for temperature below the melting temperature which makes them difficult to reveal with TPM. In fact, a close look to the melting profile given by the EMBOSS’DAN predictor (24) shows that the A50 sequence in 2000A should melt at 65°C. Yet, 2000wo and 2000A, which only differ by the A50 central sequence, exhibit similar falls in

equal to 2 nm, that is to say twice the persistence length of ssDNA. Using cyclisation assays on 0.1 kb DNA, Forties et al. (10) showed that this short persistence length is reached for a bubble with a length greater than 4 bp. Since in our buffer conditions, the predicted melting temperatures are about 80°C (Supplementary Figure S10), DNA bubbles containing more than 4 bp are very likely to be scarce for temperature below the melting temperature which makes them difficult to reveal with TPM. In fact, a close look to the melting profile given by the EMBOSS’DAN predictor (24) shows that the A50 sequence in 2000A should melt at 65°C. Yet, 2000wo and 2000A, which only differ by the A50 central sequence, exhibit similar falls in  at about 65°C as if the temperature range probed in this study was insufficient to induce the opening/denaturation of this isolated A50 sequence. The melting profile of 2060 exhibits a 300 bp central sequence, which should melt at about 70°C. In line with this prediction, 2060 seems to undergo a steep decrease in

at about 65°C as if the temperature range probed in this study was insufficient to induce the opening/denaturation of this isolated A50 sequence. The melting profile of 2060 exhibits a 300 bp central sequence, which should melt at about 70°C. In line with this prediction, 2060 seems to undergo a steep decrease in  starting from 60°C as if the extended low melting region could favour the existence of a sufficient number of DNA bubbles to be detected starting at 60°C. The formation of a large DNA bubble is indeed not expected below the melting temperature as the denaturation transition gets sharper when the size of the denatured DNA fragment increases (31). EMBOSS’DAN predictor should nevertheless be considered with care as it considers the dinucleotides to have melting capacities independent of their sequence environment (32).

starting from 60°C as if the extended low melting region could favour the existence of a sufficient number of DNA bubbles to be detected starting at 60°C. The formation of a large DNA bubble is indeed not expected below the melting temperature as the denaturation transition gets sharper when the size of the denatured DNA fragment increases (31). EMBOSS’DAN predictor should nevertheless be considered with care as it considers the dinucleotides to have melting capacities independent of their sequence environment (32).

In physiological salt conditions below 60°C, linear DNA molecules exhibit only slight changes in their global and time-averaged flexibility with temperature in our HTTPM results. Consequently, linear DNA molecules do not appear as effective temperature transducers capable to convert a rise in temperature into an increase in the global DNA flexibility and to affect linear DNA at distances exceeding several hundreds of base pairs. Nevertheless, our study does not allow one to negate the existence of a few bp-long transient bubbles, which may appear slightly more frequently when temperature rises while remaining inferior to the melting temperature. Such a local denaturation of the double stranded DNA – which already exists at room or physiological temperature, albeit with a very low probability, which grows with increasing temperature (5) – could have local consequences such as the facilitation of binding of proteins, which in turn could induce DNA bends and affect the DNA conformation on long distances. Accordingly, it was measured an increase with  in the DNA-binding affinity of Cren7 and Sul7, which are DNA bending proteins involved in the architecture of the archae nucleoid (12). Independently, it was shown a strong correlation between the breathing propensity of DNA sequences and the binding affinity of the E. coli nucleoid associated protein FIS (33), which induces bends with angles varying from 30 to 70° depending on the intrinsic shape of the DNA sequence (34). The protein binding may then amplify the impact of transient, not to say elusive, opening of a few bp bubbles by converting them into stable bends. These local curvatures could lead to further compaction of DNA as it is observed for high concentration of the previously cited DNA-bending proteins and, as such, participate directly in fine-tuning the chromosome organization.

in the DNA-binding affinity of Cren7 and Sul7, which are DNA bending proteins involved in the architecture of the archae nucleoid (12). Independently, it was shown a strong correlation between the breathing propensity of DNA sequences and the binding affinity of the E. coli nucleoid associated protein FIS (33), which induces bends with angles varying from 30 to 70° depending on the intrinsic shape of the DNA sequence (34). The protein binding may then amplify the impact of transient, not to say elusive, opening of a few bp bubbles by converting them into stable bends. These local curvatures could lead to further compaction of DNA as it is observed for high concentration of the previously cited DNA-bending proteins and, as such, participate directly in fine-tuning the chromosome organization.

Determining whether DNA bubbles exist and play a role in the biological processes is crucial as it appears that not only the DNA local sequence but also the DNA local shape influence the binding of proteins as well as the DNA deformation induced by the protein binding (34). The partial destabilization of the double stranded DNA undergoing DNA breathing has been studied using a large variety of techniques over the last fifty years (35) but the sub-millisecond dynamics of the DNA bubbles (5,36) have impeded their direct detection. This has already started to change with recent single-molecule developments which already allowed to detect the DNA breathing using internally modified DNA (37). The characterization of internally intact DNA in the 100 μs range, as we could achieve it here rigorously and quantitatively on the ∼ 1 s range using HTTPM coupled to statistical physics modelling, may be the next step to further elucidate the role of DNA bubbles.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank M. Chandler for providing pKH47.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR online.

FUNDINGS

CNRS, University of Toulouse 3; ANR-11-NANO-010 ‘TPM on a Chip’. Funding for open access charge: ANR-11-NANO-010 ‘TPM on a Chip’.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brunet A., Tardin C., Salomé L., Rousseau P., Destainville N., Manghi M.. Dependence of DNA persistence length on ionic strength of solutions with monovalent and divalent salts: a joint theory–experiment study. Macromolecules. 2015; 48:3641–3652. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hagerman P.J. Evidence for the existence of stable curvature of DNA in solution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1984; 81:4632–4636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wilcoxon J., Schurr J.M.. Temperature dependence of the dynamic light scattering of linear ϕ29 DNA: Implications for spontaneous opening of the double-helix. Biopolymers. 1983; 22:2273–2321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pal T., Bhattacharjee S.M.. Rigidity of melting DNA. Phys. Rev. E. 2016; 93:052102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Manghi M., Destainville N.. Physics of base-pairing dynamics in DNA. Phys. Rep.-Rev. Sect. Phys. Lett. 2016; 631:1–41. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holstege F.C., Tantin D., Carey M., van der Vliet P.C., Timmers H.T.. The requirement for the basal transcription factor IIE is determined by the helical stability of promoter DNA. EMBO J. 1995; 14:810–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kochoyan M., Leroy J.L., Guéron M.. Proton exchange and base-pair lifetimes in a deoxy-duplex containing a purine-pyrimidine step and in the duplex of inverse sequence. J. Mol. Biol. 1987; 196:599–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cloutier T.E., Widom J.. DNA twisting flexibility and the formation of sharply looped protein–DNA complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005; 102:3645–3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Vafabakhsh R., Ha T.. Extreme bendability of DNA less than 100 base pairs long revealed by single-molecule cyclization. Science. 2012; 337:1097–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Forties R.A., Bundschuh R., Poirier M.G.. The flexibility of locally melted DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009; 37:4580–4586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Geggier S., Kotlyar A., Vologodskii A.. Temperature dependence of DNA persistence length. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:1419–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Driessen R.P.C., Sitters G., Laurens N., Moolenaar G.F., Wuite G.J.L., Goosen N., Dame R.T.. Effect of temperature on the intrinsic flexibility of DNA and its interaction with architectural proteins. Biochemistry (Mosc.). 2014; 53:6430–6438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Plenat T., Tardin C., Rousseau P., Salome L.. High-throughput single-molecule analysis of DNA-protein interactions by tethered particle motion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012; 40:e89–e89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brunet A., Chevalier S., Destainville N., Manghi M., Rousseau P., Salhi M., Salomé L., Tardin C.. Probing a label-free local bend in DNA by single molecule tethered particle motion. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015; 43:e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Segall D.E., Nelson P.C., Phillips R.. Volume-exclusion effects in tethered-particle experiments: bead size matters. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006; 96:088306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marmur J., Doty P.. Determination of the base composition of deoxyribonucleic acid from its thermal denaturation temperature. J. Mol. Biol. 1962; 5:109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hayashi K. A cloning vehicle suitable for strand separation. Gene. 1980; 11:109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Diagne C.T., Salhi M., Crozat E., Salomé L., Cornet F., Rousseau P., Tardin C.. TPM analyses reveal that FtsK contributes both to the assembly and the activation of the XerCD-dif recombination synapse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:1721–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Blumberg S., Gajraj A., Pennington M.W., Meiners J.-C.. Three-dimensional characterization of tethered microspheres by total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy. Biophys. J. 2005; 89:1272–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bodratti A.M., Sarkar B., Alexandridis P.. Adsorption of poly(ethylene oxide)-containing amphiphilic polymers on solid-liquid interfaces: fundamentals and applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017; 244:132–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Manghi M., Tardin C., Baglio J., Rousseau P., Salomé L., Destainville N.. Probing DNA conformational changes with high temporal resolution by tethered particle motion. Phys. Biol. 2010; 7:046003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zimm B.H. Dynamics of polymer molecules in dilute solution: viscoelasticity, flow birefringence and dielectric loss. J. Chem. Phys. 1956; 24:269–278. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bingham E., Jackson R.. Standard substances for the calibration of viscometers. Bull. Bur. Stand. 2017; 14:59–86. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rice P., Longden I., Bleasby A.. EMBOSS: the European Molecular Biology Open Software Suite. Trends Genet. TIG. 2000; 16:276–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Iyer V., Struhl K.. Poly(dA:dT), a ubiquitous promoter element that stimulates transcription via its intrinsic DNA structure. EMBO J. 1995; 14:2570–2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Segal E., Widom J.. Poly(dA:dT) tracts: major determinants of nucleosome organization. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2009; 19:65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Johnson S., Chen Y.-J., Phillips R.. Poly(dA:dT)-rich DNAs are highly flexible in the context of DNA looping. PLoS ONE. 2013; 8:e75799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Visser E.W.A., van IJzendoorn L.J., Prins M.W.J.. Particle motion analysis reveals nanoscale bond characteristics and enhances dynamic range for biosensing. ACS Nano. 2016; 10:3093–3101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ha T. Single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Methods. 2001; 25:78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ermak D.L., McCammon J.A.. Brownian dynamics with hydrodynamic interactions. J. Chem. Phys. 1978; 69:1352–1360. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Blake R.D., Delcourt S.G.. Thermal stability of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998; 26:3323–3332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu F., Tøstesen E., Sundet J.K., Jenssen T.-K., Bock C., Jerstad G.I., Thilly W.G., Hovig E.. The human genomic melting map. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2007; 3:e93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Nowak-Lovato K., Alexandrov L.B., Banisadr A., Bauer A.L., Bishop A.R., Usheva A., Mu F., Hong-Geller E., Rasmussen K.Ø., Hlavacek W.S. et al. Binding of nucleoid-associated protein Fis to DNA is regulated by DNA breathing dynamics. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2013; 9:e1002881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hancock S.P., Stella S., Cascio D., Johnson R.C.. DNA sequence determinants controlling affinity, stability and shape of DNA complexes bound by the nucleoid protein Fis. PLoS ONE. 2016; 11:e0150189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. von Hippel P.H., Johnson N.P., Marcus A.H.. Fifty years of DNA “Breathing”: reflections on old and new approaches. Biopolymers. 2013; 99:923–954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Altan-Bonnet G., Libchaber A., Krichevsky O.. Bubble dynamics in double-stranded DNA. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003; 90:138101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Phelps C., Lee W., Jose D., von Hippel P.H., Marcus A.H.. Single-molecule FRET and linear dichroism studies of DNA breathing and helicase binding at replication fork junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2013; 110:17320–17325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.