Abstract

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory diseases (CIDs) are frequently treated with biological medications, specifically tumour necrosis factor inhibitors (TNFi)). These medications inhibit the pro-inflammatory molecule TNF alpha, which has been strongly implicated in the aetiology of these diseases. Up to one-third of patients do not, however, respond to biologics, and lifestyle factors are assumed to affect treatment outcomes. Little is known about the effects of dietary lifestyle as a prognostic factor that may enable personalised medicine. The primary outcome of this multidisciplinary collaborative study will be to identify dietary lifestyle factors that support optimal treatment outcomes.

Methods and analysis

This prospective cohort study will enrol 320 patients with CID who are prescribed a TNFi between June 2017 and March 2019. Included among the patients with CID will be patients with inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis), rheumatic disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis, psoriatic arthritis), inflammatory skin diseases (psoriasis, hidradenitis suppurativa) and non-infectious uveitis. At baseline (pretreatment), patient characteristics will be assessed using patient-reported outcome measures, clinical assessments of disease activity, quality of life and lifestyle, in addition to registry data on comorbidity and concomitant medication(s). In accordance with current Danish standards, follow-up will be conducted 14–16 weeks after treatment initiation. For each disease, evaluation of successful treatment response will be based on established primary and secondary endpoints, including disease-specific core outcome sets. The major outcome of the analyses will be to detect variability in treatment effectiveness between patients with different lifestyle characteristics.

Ethics and dissemination

The principle goal of this project is to improve the quality of life of patients suffering from CID by providing evidence to support dietary and other lifestyle recommendations that may improve clinical outcomes. The study is approved by the Ethics Committee (S-20160124) and the Danish Data Protecting Agency (2008-58-035). Study findings will be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, patient associations and presentations at international conferences.

Trial registration number

NCT03173144; Pre-results.

Keywords: lifestyle and chronic inflammatory disease, biomarker and lifestyle, personalized medicine, patient related outcome measures, treatment outcome, western style diet

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study includes a number of diseases treated with biologics, targeting the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumour necrosis factor alpha.

All evaluations will be performed as part of a prospectively designed cohort study using established disease-specific scoring systems.

As comparisons between diseases are limited by disease-specific scoring systems, additional response criteria (eg, quality of life and disability) will be used for analysis.

The sample size is limited.

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory diseases (CIDs) are a diverse set of immunological diseases that include inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)), rheumatic conditions (rheumatoid arthritis (RA), axial spondyloarthropathy (axSpA), psoriatic arthritis (PsA)), inflammatory skin diseases (psoriasis (PsO), hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)) and eye disease (non-infectious uveitis (NiU)). The pro-inflammatory cytokine tumour necrosis factor α (TNF) is recognised to play an important role in the aetiology of these diseases. Correspondingly, biological agents that inhibit TNF, also known as TNF inhibitors (TNFi), are an important component of treatment. However, a large number of patients do not benefit from TNFi treatment.1

CIDs have a large and negative impact on both individual patients and at a community level as a consequence of health-related workplace productivity loss and health system expense, which is largely influenced by the high cost of providing biological medications.1 CIDs are recurring, lifelong illnesses of potentially early onset that can substantially affect the life quality of patients and their families.2–5 In addition, they are prevalent diseases with IBD affecting 0.5% of the population in the Western world,6 and RA and PsO affecting respectively 0.3%–1.0% and 1.5% of the global population.7 8 Furthermore, the disease burden, and hence health system burden, is predicted to rise dramatically due to population growth, ageing demographics and increasing disease incidence.9–11

The diseases may have overlapping symptoms.12 For example, some patients with NiU and axSpA may experience bowel symptoms, and some patients with IBD may develop extraintestinal manifestations (ie, eye, joint and skin symptoms). The diseases are rather complex with both genetic and environmental factors implicated in aetiology. While CIDs share some genetic and environmental predisposing factors, other susceptibility factors differ.13 The genetic architecture of CIDs has previously been investigated by large international consortia.14–20 Similarly, environmental factors have been investigated in large cohorts with prospectively collected lifestyle data, such as the European Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition Study as well as the Nurses’ Health Study.21–35

In light of the notable impact that environment factors play in disease development, which is further supported by the increasing incidence of these disease,6 11 it stands to reason that modifying environment factors such as lifestyle may influence treatment response. Accordingly, quite a few patients ask their healthcare professionals for lifestyle recommendations that can influence the effectiveness of treatment, and in particular the outcomes achieved with TNFi.

Evidence-based research

In an attempt to increase value and reduce waste in research, a systematic review of existing evidence was performed prior to embarking on this study.36 In a recent systematic review examining the impact of diet on TNFi response in IBD,37 it was concluded that there is scarce evidence linking TNFi treatment response to specific dietary recommendations; hence, there is a clear research need. Similarly, only a few large prospective studies have assessed the effects of lifestyle on TNFi-treated patients with CID.38 One prospective study compared partial enteral nutrition (16 patients), exclusive enteral nutrition (22 patients) and TNFi (52 patients) therapy in 90 paediatric patients. There were no significant differences in clinical response rates between the three treatment arms, although the rate of patients that achieved a faecal calprotectin concentration of ≤250 µg/g was higher among the TNFi-treated patients.39

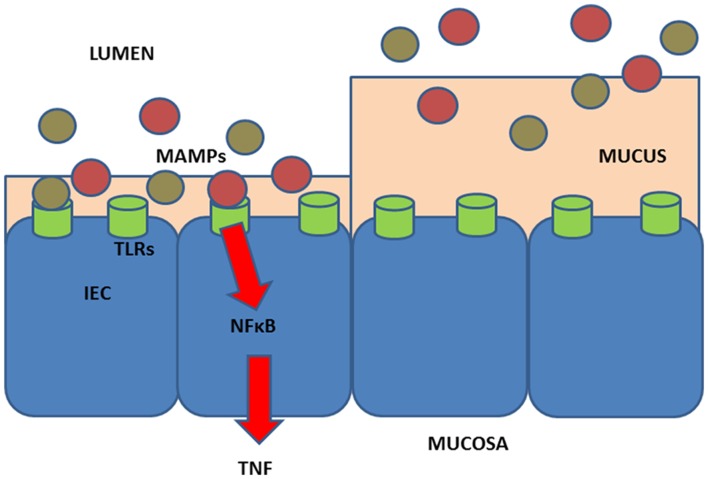

More recently, lifestyle factors, as they relate to TNFi therapy among patients with CID, were identified as an area for further investigation.40 To explore different hypotheses, we included studies that may be subject to recall bias or bias introduced by lifestyle changes due to the disease itself, for example, smoking, physical activities and intake of Western-style diet.40 After reviewing these potential hypotheses, we proposed a model, whereby a diet high in meat and low in fibres may impact inflammation and TNFi treatment37 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hypothesis for effects of diet in relation to treatment effect. (Left) Low levels of fibre intake may promote microbial metabolism of mucus as the main energy source.37 75 76 This will lead to decrease of the mucus layer. Further, degradation of mucus releases free sulfate, which would then become available for use by sulfate-reducing bacteria (eg, Bilophila wadsworthia) for microbial produced hydrogen sulfide.77 In addition, high intake of food containing organic sulfur and sulfate additives, such as meat and processed meat, may increase the amount of sulfate for microbial produced hydrogen sulfide.78 79 The resultant hydrogen sulfide from low intake of fibre and high intake of meat may reduce the disulfide bonds in the mucus network rendering the mucus layer penetrable to, for example, bacteria.77 80 Then, MAMPs from microbes or contained in the diet may reach the epithelium and activate the pattern recognition receptors such as TLRs on the enterocytes (IEC) and next activate NFkB, type I interferon and other inflammatory pathways. This leads to production of pro-inflammatory (TNF, IL-1β, IL-6, IFN, IL-17, etc), and anti-inflammatory (primarily IL-10) cytokines and chemokines that will next activate innate lymphocytic cells and other immune cells and the immune system in general.81 82 There is some support for such a mechanism in chronic inflammatory disease, including findings of high amounts of sulfate-reducing bacteria in patients with UC77 83; an association between the highest tertile of carbohydrate-restricted diet and RA, in a nested case–control study among 386 individuals who developed RA and 1886 matched controls from the Swedish Västerbotten Intervention Program cohort with prospectively sampled dietary survey84; association of high-fibre intake with low risk of Crohn’s disease among 170 776 participants from the prospective Nurses’ Health Study I23; association of high intake of red meat and total protein and risk of developing inflammatory polyarthritis in the population-based prospective cohort of 25 630 participants from the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer in Norfolk.35 Finally, a prospective study of 191 patients with UC in remission found that high consumption of meat, particularly red and processed meat, protein and alcohol was associated with risk of relapse, and that high sulfur or sulfate intakes may offer an explanation for the observed findings.85 Additionally, support of the notation that diet may affect systemic immune response is provided by the finding that intake of low glycaemic index diet was found to lower secretion of TNF and IL-6 from stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells from obese humans.86 (Right) Intake of high fibre and low meat may promote an effective mucosal barrier and support the effects of outcome after drug targeting the pro-inflammatory molecule TNF (TNF inhibitors). Intake of soluble plant fibre has been found to block bacterial adhesion to gut enterocytes in animal and cell studies.87 The genetic architecture of the individual may also impact the influence of lifestyle factors.15 Hence, to provide lifestyle recommendations, we need to understand the effects of lifestyle on the immune system and how lifestyle may improve the therapeutic outcome and reduce the need of medical treatment in the individual person. Information on diet and non-diet lifestyle exposures may be collected by using, for example, questionnaires and lifestyle-associated biomarkers or a combination of these methods.88–90 Evidence-based biomarkers for lifestyle assessment are scarce91–111 and mostly used for studies on healthy individuals.112–115 IEC, intestinal epithelial cells; IL, interleukin; MAMPS, microbial-associated molecular patterns; NFkB, nuclear factor kappa B; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TLR, Toll-like receptors; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Based on previous evidence, we set out to prospectively identify dietary factors that support optimal TNFi treatment outcomes, with the ultimate aim of improving the quality of life of patients with CID.

Aims and hypotheses

The primary aim of this prospective cohort study is to investigate whether treatment outcomes in patients with CID vary with dietary differences. The main hypothesis is that ‘Diets high in fibre AND low in red and processed meat are associated with improved treatment outcomes’. Secondary aims are whether and to what extent lifestyle-associated biomarkers have prognostic value for differentiating responders from non-responders based on both disease-specific and generic treatment outcomes.

Methods and analyses

Design

This study is a prospective cohort study that will examine disease activity after initiating TNFi treatment. The primary endpoint will be assessed 14–16 weeks after initiation of a TNFi and will be defined based on the specific CID condition. The cohort will be classified as responders (including those who continue with drug treatment) or non-responders (including those who discontinue drug treatment) based on the disease-specific criteria defined below. The decision to discontinue therapy is assumed to be based on a shared decision-making process between patients and their physicians and to be supported by principles outlined in disease-specific guidelines.41

Setting

This multicentre study reflects a collaboration between the following centres: (1) Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Aalborg University Hospital; (2) Department of Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Aarhus University Hospital; (3) Diagnostic Centre, Silkeborg Regional Hospital; (4) Department of Internal Medicine, Herning Regional Hospital; (5) Department of Gastroenterology, Herlev Hospital; (6) Organ Centre, Hospital of Southern Jutland; (7) Department of Gastroenterology, Hospital of South West Jutland; (8) Department of Medical Gastroenterology, Department of Rheumatology, Department of Dermatology and Allergy Centre and Department of Ophthalmology, Odense University Hospital. Study enrolment will take place between 15 June 2017 and 31 March 2019 or until the study has enrolled a minimum of 100 patients with IBD, 100 patients with RA and 120 patients with axSpA, PsA, PsO, HS and NiU.

Patient characteristics and eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: patients ≥18 years with CID who are beginning TNFi therapy, who have not previously received TNFi treatment and who are able to read and understand Danish. Exclusion criteria: patients who have previously received a biological treatment and patients who by virtue of illiteracy or cognitive impairment are unable to complete the questionnaire.

Clinical data (table 1) will include personal data, data on health and disease, dietary and non-dietary lifestyle information, laboratory measurements and disease activity scores including patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), clinical assessments and laboratory data. Participants will complete validated questionnaires on disease activity, quality of life and lifestyle using an electronic link. Studies have revealed electronic questionnaires to be comparable to paper based in relation to the outcomes (ie, PROMs).42 43

Table 1.

Collection of patient characteristics, outcome measures and explanatory variables

| Variable | Pre | Week 14–16 |

| Clinical data* | ||

| Gender (F, M) | X | |

| Age (years) | X | |

| Diagnosis (disease) | X | |

| Onset of diagnosis (year)† | X | |

| Education (level)‡ | X | |

| Menopause (year) | X | |

| Comorbidity (diseases, Charlson index) | X | |

| Medication (predefined choices) | X | X |

| Diet (FFQ) (predefined choices) | X | |

| Changes in diet (predefined choices) | X | |

| Non-dietary lifestyle factors‡ (predefined choices) | X | X |

| Investigations: | ||

| Height (cm) | X | |

| Weight (kg) | X | X |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | X | X |

| Routine blood analyses§ | X | X |

| Endoscopy¶ | X | X |

| Biological samples** | ||

| Fasting blood samples | X | X |

| Faeces samples | X | X |

| Urine samples | X | X |

| Biopsies¶ | X | X |

| CD | ||

| Disease location (predefined choices) | X | |

| Prior operations (y/n, description) | X | |

| Disease behaviour (fistulising, luminal) | X | |

| Perianal involvement (y/n) | X | |

| STRIDE—(y/n) | NA | X |

| Abdominal pain (y/n) | X | X |

| Diarrhoea (y/n) | X | X |

| Altered bowel habit (y/n) | X | X |

| SES-CD (score) | X | X |

| Presence of ulcers (score) | X | X |

| Ulcerated surface (score) | X | X |

| Affected surface (score) | X | X |

| Presence of narrowing (score) | X | X |

| Number of affected segments (score) | X | X |

| Alterations of cross-sectional imaging (MR, CT, UL) (y/n)†† | X | X |

| HBI index (score) | X | X |

| HBI of 4 or less (y/n)‡‡ | X | X |

| General well-being (score) | X | X |

| Abdominal pain (score) | X | X |

| No of liquid stools per day (N) | X | X |

| Abdominal mass (score) | X | X |

| Manifestations (abscess, fistulas, fissures, arthralgia, uveitis, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, mouth ulcers, one point for each) (N) | X | X |

| Physician global assessment (score) | X | X |

| Physician global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Patient global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Corticosteroid-free remission§§ (y/n) | X | |

| Concomitant medication (y/n, predefined choices) | X | X |

| Number of draining fistulas (fistulising CD) | X | X |

| UC | ||

| Disease location (predefined choices) | X | |

| Prior operations (y/n, description) | X | |

| STRIDE criteria (y/n) | NA | X |

| Rectal bleeding (y/n) | X | X |

| Altered bowel habit (y/n) | X | X |

| Endoscopic remission (Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0–1) | X | X |

| Mayo clinical score of 2 or less with no individual subscore of >1‡‡ | X | X |

| Mayo ‘normal mucosal appearance’ (y/n) | X | X |

| Mayo clinical response§§ (y/n)¶¶ | X | X |

| Mayo clinical score (score) | X | X |

| Mayo endoscopic subscore (score) | X | X |

| Stools (score) | X | X |

| Rectal bleeding (score) | X | X |

| Physician global assessment (score) | X | X |

| SCCAI (score) | X | X |

| Bowel frequency (day) (score) | X | X |

| Bowel frequency (night) (score) | X | X |

| Urgency of defecation (score) | X | X |

| Blood in stool (score) | X | X |

| General well-being (score) | X | X |

| Extracolonic features (one per manifestation) | X | X |

| Physician global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Patient global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Corticosteroid-free remission§§ (y/n) | X | |

| Concomitant medication (y/n, predefined choices) | X | X |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Positive for anti-CCP/RF (y/n) | X | |

| Swollen joint count (of 28/66 joints examined) | X | X |

| Tender joint count (of 28/68 joints examined) | X | X |

| DAS28-CRP (score) | X | X |

| SDAI (score) | X | X |

| ACR20 (y/n)‡‡ | NA | X |

| ACR50 (y/n) | NA | X |

| ACR70 (y/n) | NA | X |

| EULAR good or moderate response (y/n) | NA | X |

| Low disease activity (DAS28<3.2) | NA | X |

| DAS28 remission (DAS28<2.6) | NA | X |

| Physician global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Patient global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Patient assessment of pain (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| HAQ (score) | X | X |

| axSpA | ||

| Positive for HLA-B27 (y/n) | X | |

| BASDAI (score) | X | X |

| BASFI (score) | X | X |

| BASMI (score) | ||

| Total score for back pain (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Patient global assessment of disease activity (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Patient assessment of pain (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Physician global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| ASAS20 (y/n)‡‡ | NA | X |

| ASAS40 (y/n) | NA | X |

| ASAS partial response (y/n) | NA | X |

| ASAS5/6 response (y/n) | NA | X |

| PsA | ||

| Dactylitis (y/n) | X | X |

| Enthesitis (y/n) | X | X |

| PASI (score) | X | X |

| PASI 75 response (y/n) | NA | X |

| PASI 90 response (y/n) | NA | X |

| ACR20†† | NA | X |

| Swollen joint count (of 28/66 joints examined) | X | X |

| Tender joint count (of 28/68 joints examined) | X | X |

| DAS28-CRP (score) | X | X |

| Patient global assessment of disease activity (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Patient assessment of PsA pain (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Physician global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| SDAI | X | X |

| HAQ (score) | X | X |

| PsO | ||

| Psoriatic arthritis (y/n) | X | X |

| PASI (score) | X | X |

| PASI75 response (y/n)‡‡ | NA | X |

| PASI90 response (y/n) | NA | X |

| Patient global assessment of disease activity (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Patient assessment of PsA pain (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Physician global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| DLQI (score) | X | X |

| Hidradenitis suppurativa | ||

| HiSCR response‡‡ | NA | X |

| Hurley stage*** (score) | X | X |

| Previous systemic treatment (y/n, description) | X | |

| Prior surgery (y/n, description) | X | |

| Lesion counts (N) | X | X |

| Total no. of abscesses and inflammatory nodules (N) | X | X |

| No. of abscesses (N) | X | X |

| No. of inflammatory nodules (N) | X | X |

| No. of draining fistulas (N) | X | X |

| Modified Sartorius score (score) | X | X |

| Percentage of participants who achieve abscess and inflammatory nodule (AN) count of 0, 1 and 2, respectively | X | X |

| Patient global assessment of skin pain (score) | X | X |

| DLQI (score) | X | X |

| NiU | ||

| SUN (score) | X | X |

| Uveitis treatment failure (y/n)‡‡ | NA | X |

| New active, inflammatory chorioretinal or retinal vascular lesions relative to baseline (y/n) | X | X |

| Inability to achieve ≤0.5+ or a two-step increase relative to best state achieved at all visits in anterior chamber cell grade or vitreous haze grade (y/n) | X | X |

| Worsening of best-corrected visual acuity by ≥15 letters relative to best state achieved (y/n) | X | X |

| Health-related quality of life††† | X | X |

| SF12 (score) | X | X |

| SHS (score) | X | X |

| Physician global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Patient global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | X | X |

| Rome-III (score) | X | X |

| NYHA (score) | X | X |

| Continuation of anti-TNF treatment (y/n, predefined choices for stopping if no) | X | X |

| Adverse events | ||

| Discontinuation due to adverse events (y/n) | X | |

| Serious adverse event (y/n) | X | |

| Death (y/n) | X | |

| Occurrence of surgery (y/n) | X | |

| Occurrence of hospital admission (y/n) | X | |

| Occurrence of disease-related complication (y/n) | X | |

| Laboratory§ | ||

| CRP (mg/L)‡‡‡ | X | X |

*Data will be collected using a questionnaire as well as local and national registries.

†Registry data will be retrieved from the Danish registries using the Danish individual civil registration number (CPR) including BIO-IBD,116 DANBIO,117 DERMBIO118 (database on IBD, RA, HS, axSpA, PsA and PsO patients on biological therapy), the National Patient Registry (eg, comorbidity), registries on medication and use of receipts, local laboratory databases (laboratory data) and the electronic patient records (side effects).

‡Lifestyle (dietary and non-dietary) will be registered using a validated FFQ that includes food items and a photographic food atlas of picture series of portion sizes will be used to assess intake of food groups, such as meat and dairy, and calculate total energy, fibre, protein, fat, sugar and carbohydrate intakes as well as glycaemic index and load. In addition, questions on non-diet lifestyle factors (smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption and use of over-the-counter medicine (use of probiotics, prebiotics, painkillers, laxative and antidiarrhoea agents)) as well as educational level and year of menopause (female) are included.63 The follow-up questionnaire is identical to the initial questionnaire apart from the questions on food items that only contain questions on changes of diet since the last questionnaire.

§Routine blood analyses include CRP, haemoglobin, erythrocyte count, haematocrit, erythrocyte mean cell volume, mean cell haemoglobin and mean cell haemoglobin concentration, leucocyte count, differential count, thrombocytes, K+, Na+, creatinine, coagulation factor II+VII+X, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transferase, haemoglobin glycation, lipids (cholesterol, high-density, low-density cholesterol) and transglutaminase.

¶Only patients with IBD.

**From all participants, blood, urine and faeces are sampled. In addition, from patients with IBD, intestinal biopsies are sampled. In selected cases, the additional biological material on participants from this study may be retrieved from the Patobank and the Danish Biobank. The samples will be collected adhering to the Sample PRE-analytical Code and Biospecimen Reporting for Improved Study Quality guidelines, using standard operational procedures describing and logging primary container, centrifugation conditions, centrifugation parameters and storage conditions.120 121 The biological material will be stored at Odense Patient data Explorative Network (OPEN) (biological material from Odense University Hospital) or at SHS (biological material from the other hospitals).

††Only patients with CD when endoscopy cannot adequately evaluate inflammation.

‡‡Primary endpoint for the individual diseases

§§Corticosteroid-free remission. Clinical remission in patients using oral corticosteroids at baseline (pre) that have discontinued corticosteroids and in clinical remission at first follow-up.

¶¶A reduction in complete Mayo score of ≥3 points and ≥30% from baseline (or a partial Mayo score of ≥2 points and ≥25% from baseline, if the complete Mayo score was not performed at the visit) with an accompanying decrease in rectal bleeding subscore of ≥1 point or absolute rectal bleeding subscore of ≤1 point.

***Data for the Hurley stage reflect actual assessment. A patient’s overall Hurley stage is the highest stage across all affected anatomical sites. Stage I is defined as the localised formation of single or multiple abscesses without sinus tracts or scarring, stage II as recurrent abscesses (single or multiple) with sinus tract formation and scarring and stage III as multiple abscesses with extensive, interconnected sinus tracts and scarring.

†††All participants will be asked whether they have any complaints regarding or are known with diseases affecting the bowel, the skin, rheumatic complaints and so on, and if no to both questions they will not be asked to complete the relevant questionnaire.

‡‡‡Biological response defined as a drop in CRP level of more than 25% or to the normal level among patients with an elevated CRP before treatment (higher than normal range).119

ACR, American College of Rheumatology; ASAS, Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society; axSpA, axial spondyloarthropathy; BASDAI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index; BASFI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index; BASMI, Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index; CCP/RF, cyclic citrullinated peptide/rheumatoid factor; CD, Crohn’s disease; CRP, C-reactive protein; DAS, Disease Activity Score; DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; EULAR, European League Against Rheumatism; FFQ, Food Frequency Questionnaire; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; HBI, Harvey-Bradshaw Index; HiSCR, Hidradenitis Suppurativa Clinical Response; HLA-B27, human leucocyte antigen; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; K+, potassium; NA, not applicable; N+ sodium; NiU, non-infectious uveitis; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; PsO, psoriasis; SCCAI, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index; SES-CD, Simple Endoscopic Score for Crohn’s Disease; SF12, Short Form Health Survey; SHS, Short Health Scale; STRIDE, Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease; SUN, Standardization of Uveitis Nomenclature for Reporting Clinical Data; TNF, tumour necrosis factor; UC, ulcerative colitis; UL, ultrasound; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; y/n, yes/no.

Primary and secondary endpoints

Primary endpoint

The predefined primary endpoint will be the proportion of patients with a clinical response to therapy 14–16 weeks after treatment initiation. Below are the disease-specific definitions of clinical response to therapy:

Crohn’s disease: clinical remission, defined as Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) of 4 or less;44

Ulcerative colitis: clinical remission, defined as Mayo Clinic Score of 2 or less (with no individual subscore of >1);45

rheumatoid arthritis: clinical response, defined as at least a 20% improvement according to the criteria of the American College of Rheumatology (ACR20);46

axial spondyloarthritis: clinical response, defined as at least a 20% improvement according to the Assessment of Spondyloarthritis International Society (ASAS20);47 48

psoriatic arthritis: clinical response, defined as at least a 20% improvement according to the criteria of ACR20;49

psoriasis: clinical response, defined as at least a 75% improvement in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI 75);50

hidradenitis suppurativa: clinical response, defined as at least a 50% reduction in the abscess and inflammatory-nodule count, with no increase in abscess or draining-fistula counts (HiSCR response);51

non-infectious uveitis: clinical response, defined as those who did not have a treatment failure (treatment failure will be based on assessment of new inflammatory lesions, best-corrected visual acuity, anterior chamber cell grade and vitreous haze grade).52

Key secondary outcomes

Major secondary outcomes, also to be measured 14–16 weeks after treatment initiation, include disease-specific outcome measures that cover core outcome sets, the generic health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and disability at endpoint. Below are a list of disease-specific secondary outcomes.

CD: Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE; abdominal pain, diarrhoea, altered bowel habit, SES-CD (presence of ulcers, ulcerated surface, affected surface, presence of narrowing, number of affected segments), alterations of cross-sectional imaging (MR, CT, ultrasound) (only when endoscopy cannot adequately evaluate inflammation)), HBI (general well-being, abdominal pain, number of liquid stools per day, abdominal mass, extraintestinal manifestations (abscess, fistulas, fissures, arthralgia, uveitis, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, mouth ulcers)), physician global assessment, number of draining fistulas, corticosteroid-free remission, concomitant medication.

UC: STRIDE (rectal bleeding, altered bowel habit, endoscopic remission (Mayo endoscopic subscore of 0–1)), Mayo Clinical Score (Mayo endoscopic subscore, stools, rectal bleeding, physician global assessment), Mayo ‘normal mucosal appearance’, Mayo clinical response, Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index (bowel frequency (day), bowel frequency (night), urgency of defecation, blood in stool, general well-being, extracolonic features), physician global assessment, corticosteroid-free remission, concomitant medication.

RA: Tender joints, swollen joints, pain, physician global assessment, patient global assessment, Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ), C reactive protein (CRP), Disease Activity Score (DAS)28-CRP, Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI).

Axial spondyloarthropathy: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Metrology Index (BASMI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Functional Index (BASFI), Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis DAI, total score for back pain, physician global assessment, patient global assessment, CRP.

Psoriatic arthritis: tender joints, swollen joints, psoriatic arthritis pain, physician global assessment, patient global assessment, HAQ-DI, CRP, DAS28-CRP, SDAI, PASI.

Psoriasis: PASI, physician global assessment, patient global assessment, psoriatic arthritis pain, Dermatology Life Quality Index total score.

Hidradenitis suppurativa: percentage of participants who achieve abscess and inflammatory nodule (AN) count of 0, 1 and 2, respectively, patient’s global assessment of skin pain, modified Sartorius score.

Non-infectious uveitis: new active, inflammatory chorioretinal or retinal vascular lesions relative to baseline, inability to achieve ≤0.5+ or a two-step increase relative to the best state achieved at all visits in anterior chamber cell grade or vitreous haze grade, worsening of best-corrected visual acuity by ≥15 letters relative to best state achieved.

Exploratory secondary (tertiary) outcomes

Additional exploratory outcomes will include biological measures, disease-specific disease activity measures as individual measure and combined scores as well as changes of these (including those measured by physician/patients such as patients’ health-related quality of life) at first clinical follow up53 (week 14–16) (table 1). Other outcomes include changes in the use of concomitant medication, achievement of steroid-free remission, serious adverse events such as hospitalisation and the need for surgery at first clinical follow-up (table 1).53

Prognostic factors

Primary exposure variable

For the primary prognostic model, the primary exposure variables will be prioritised in the following order:

The upper tertile of the sample (33.3% of the total sample), based on the ratio of fibre to meat intake, is associated with better treatment outcomes.

The lower tertile of the sample (33.3% of the total sample) with respect to intake of red and processed meat and the upper tertile of the sample (33.3% of the total sample) with respect to intake of dietary fibres are independently associated with better treatment outcomes, and a potential interaction between them may further improve treatment outcomes.

Other (exploratory) exposure variables

other lifestyle factors independently or combined (red and processed meat intake, vegetable intake, dietary fibre intake, cereal intake, gluten consumption, legume intake, red wine consumption, dairy product intake, amount of physical activity, smoking status, total protein/fat, protein/fat from red and processed meat, glycaemic index);

pretreatment lifestyle-associated biomarkers;

combinations of lifestyle factors and lifestyle-associated biomarkers;

gene–environment interaction analyses;

pretreatment levels of inflammatory molecules.

Data management

The electronic questionnaire is in Danish. Participants will access the questionnaire by an electronic link which will be sent to their personal, electronic mailbox. All data will be stored in a secure research storage facility.54 Information registered by clinicians and technicians will periodically be transferred from paper format to electronic format using either double entry of data or automated forms processing.55

No patient risks are foreseen as a direct result of this project. Clinicians will treat enrolled patients in the same fashion as non-enrolled patients. As a consequence, no data monitoring committee will be established.

Statistical methods

Prognostic factor research was developed to aid healthcare providers in estimating the probability or risk that a specific event will occur in the future. Hence, it has the potential to inform clinical decision-making.56 Conceptually, a good prognostic model is one that functions for patients other than those from whom the data was derived.57 Our intention is to use data obtained from this rigorously designed, prospective cohort study to explore our ability to predict clinical response across specific CID conditions (Y=primary endpoint) and to explore whether diets high in fibre AND low in red and processed meat (X=assessed at baseline) are an informative prognostic factor. Per default, the statistical models will include the specific CID condition and the clinical centre as fixed effects. Specific details will be part of the final statistical analysis plan (SAP). In terms of transparency, when reporting the multivariable models, the study will adhere to guidelines from the ‘Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis’.

Sample size considerations

Deciding sample size is a well-known difficulty with exploratory prognostic factor research studies. To obtain an adequate number of outcome events, we apply ‘the rule of thumb’, whereby 10 outcomes are needed for each independent variable. We plan to enrol 320 patients in total and we anticipate that 50% of these will experience a clinical response during the 14–16 weeks period after TNFi initiation.1 With this in mind, and anticipating that we will see at least 160 events (ie, clinical response among the 320 patients), the study is sufficiently powered to explore the impact of as many as 16 independent variables including condition and clinical centre. Since using the ‘rule of thumb’ method to justify sample size is a debated practice, we went one step further and estimated the statistical power to detect differences between two dietary groups. For the contrast between groups and for a comparison of two independent binomial proportions (those with high-fibre and low-meat intake vs other) using Pearson’s χ2 statistic, with a χ2 approximation, with a two-sided significance level of 0.05 (P<0.05), a total sample size of 318—assuming an ‘allocation ratio’ of 1 to 2 (one-third)—has an approximate power of 0.924 (ie, >90% statistical power) if the anticipated proportions responding are 60% and 40%, respectively.

Statistical programming will be done using the software SAS V.9.4(SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), STATA or R, with transparent reporting of the source code used to analyse the data. Computational details will be available in the prespecified SAP. These will be finalised before data collection is complete. Our primary analysis set will be based on observations available at the time of study closure. In other words, we will consider ‘Data as observed’ to be our primary resource for statistical inference. However, for the purpose of sensitivity, multiple sensitivity analyses will be performed to assess the robustness of the primary analyses, including analyses based on the ‘Non-responder-imputation’ and multiple-imputation analyses, which are based on model-based approaches for missing data (these details will be available in the final SAP). A simplistic ‘null responder imputation’ would represent a conservative base case and is likely valid even if data is ‘missing not at random’,58 as it assumes, and implies that patients have not improved or have worsened after entering the study.

No interim analyses will be performed. All reported P values will be two sided, and by default, these will not be adjusted for multiple comparisons. However, due to potential issues of multiplicity, as multiple statistical tests will be performed in the study, we will interpret ‘statistically significant’ findings in the context of whether the 95% CI excludes outcomes that could be perceived as clinically important. We will use the following consistent language to describe effects that might appear as chance findings: “The prognostic factor appears to have little or no effect on the clinical outcome if the point estimate or the boundaries of the 95% CI lies between 0.80 and 1.25”. Thus, despite an apparently statistically significant finding (P<0.05), a relative point estimate within the range of 0.80 and 1.25 will not be considered a clinically meaningful effect.

The Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ) we use in the present study has been widely used in prospective cohort studies, including in European prospective investigations in the fields of oncology and chronic diseases.59 60 It has been extensively used and evaluated in the Danish population, and results from different methods demonstrate consistency.61 62 However, the FFQ is not without limits, in particular with respect to the lack of information on portion sizes.63 64 We, therefore, modified the FFQ to capture information on portion size.63 A second potential limitation relates to comprehensive questionnaire completion. However, in a pilot study of 10 hospital patients (50–70 years of age) the FFQ was completed within 40–50 min and no complaints were reported. The imprecision of the FFQ will lead to large CIs. The result will most likely lead to null results (rather than type 2 errors). The disease groups are expected to vary in several aspects such as age, gender and body mass index. We will, however, be unable to determine the potential effect of selective diet reporting on responders and non-responders.65 On the other hand, studies have suggested that dietary patterns are relatively stable among adults in the Danish population.66 Due to study design and the limited number of participants, this study may not capture every lifestyle difference between responders and non-responders. Similarly, this study has only limited power to detect gene–environment interactions. To avoid potential type 2 errors, it is important that the results are replicated in other well-characterised patient populations using prospectively sampled dietary information. To further evaluate the robustness of the results, study results would preferably be replicated in cohorts from other countries.

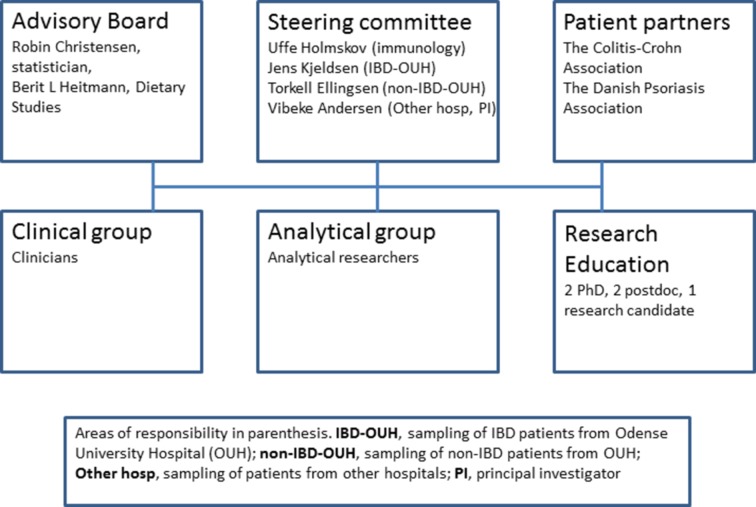

Project organisation

The study team is organised into three significant groups: a clinical research group (CRG), an analytical research group (ARG) (figure 2) and a steering committee (SC). The CRG includes specialists from gastroenterology, rheumatology, dermatology and ophthalmology who will be implicated in the clinical care and assessment of study participants. The ARG will be responsible for performing laboratory analyses on the collected biological material. Finally, the SC—whose members include Professor Uffe Holmskov, Professor Jens Kjeldsen, Professor Torkell Ellingsen and Professor Vibeke Andersen—are responsible for planning and organising the study within the appropriate legal framework, facilitating meetings for the three study groups and for scientific follow-up. The group as a whole, including clinicians and analysts, is responsible for the scientific results and budget.

Figure 2.

Organisation and patient research partners. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Collaboration between patients and health professionals on research projects is a relatively new phenomenon.67–69 The involvement of patients in research (patient research partners (PRPs)) will ideally will give a stronger voice to patients’ views on research, specifically with respect to research priorities. Furthermore, individual patients and patient organisations can contribute to research study design, preparing educational material, discussing results, disseminating results and recruiting study participants. Recommendations on incorporating PRPs into research study processes suggest that they should be provided with relevant support and education. With this initiative, we were keen to gain experience with PRPs. Thus, this project was built with input from the Danish Colitis-Crohn’s Association, represented by its director Charlotte Lindgaard Nielsen, the Danish Psoriasis Association, represented by its director Lars Werner and three individual patients with RA from one of the participating clinical departments.

The SC will hold telephone conferences every 2–4 weeks, but more often when necessary, and face-to-face meetings 3–4 times per year. Among participants, the SC will organise telephone conferences every 2–4 weeks, again more often when necessary, and face-to-face meetings at the time of enrolment and every year thereafter until the conclusion of the study.

Perspectives

The use of prognosis research evidence at multiple stages is central to the process of translational research, with the ultimate goal of improving patient outcomes. Prognosis research includes various aspects of importance to healthcare professionals, enabling them to guide individual patients in terms of shared decision-making via overall prognosis, knowledge on important prognostic factors or models and subsequently (from randomised trial evidence) stratified medicine.56 70–72 We anticipate that BELIEVE study will reveal prognostic factors of importance, including whether the diet of the patient is likely to interfere with the outcome of being prescribed a TNFi treatment. Hopefully, by combining various phenotype and genotype aspects into the prognostic models, BELIEVE study will add value to the long-term goal of achieving ‘personalised medicine’.

We will seek to replicate findings that are identified as having prognostic value in other prospective cohorts, including from a planned study of CID cases from the Danish ‘Diet, Health and Cancer’ cohort and potentially from other cohorts with lifestyle data.73 74

Dissemination of results to the public and scientifically

The target journal for the primary outcome will be a general medical journal directed at family physicians. Family physicians see patients with CID across the entire spectrum of disease. Moreover, lifestyle recommendations are an important element of general practice. Hence, although family physicians are not necessarily the primary decision-makers with respect to treatment of patients with CID, a role more ably assumed by specialists, they have considerable influence on lifestyle decisions for patients with CID. Subsequently, other hypotheses will be analysed and manuscripts prepared (independent of findings), with the intention of submitting additional articles to specialised journals in the areas of nutrition, immunology, gastroenterology, rheumatology, dermatology and ophthalmology.

Authorship confers credit and has important academic, social and financial implications and therefore any authorship on manuscripts coming from BELIEVE study is associated with responsibility and accountability for the published work. Thus, we intend to follow the recommendations of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) to ensure that contributors who have made substantive intellectual contributions to a paper are given credit as authors, but also that contributors credited as authors understand their role in taking responsibility and being accountable for the published work.

The ICMJE criteria for authorship was designed to distinguish authors from other contributors based on the following four criteria: (1) substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis or interpretation of data for the work; (2) drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; (3) final approval of the version to be published and (4) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

In addition to the scientific reporting of results, major findings with translational implications will be communicated to health professionals, patient organisations, public health policy-makers and to the general public through various media and news activities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Lina A Knudsen and Mark Unger are thanked for English proofreading.

Footnotes

Contributors: VA, BLH and RC wrote the first draft. All other authors, KWA, OHN, SBS, MJ, AB, LH, JG, JW, HG, UF, JAV, SGK, JF, SAGRM, TK, JB, JF, JFD, ABB, GLS, ST, NJF, IB, TBB, AS, EBS, AF, DE, PR, JR, MB, LW, CLN, HLM, ABN, TK, JK and UH contributed to the conception and design of the study. All authors accepted the final submitted version.

Funding: This project is part of a project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 733100” (P Rosenstiel, A Franke, J Raes, V Andersen). Funding has furthermore been received from Odense Patient data Explorative Network (OPEN) (OP-332, V Andersen), “Knudog Edith Eriksen’s Mindefond” (V Andersen), Region of Southern Denmark (V Andersen), University of Southern Denmark (V Andersen, U Holmskov). The Parker Institute, Bispebjerg and Frederiksberg Hospital (R Christensen, B L Heitmann) are supported by a core grant from the Oak Foundation (OCAY-13-309).

Competing interests: All authors declare no conflict of interest. However, the following authors declare: B. Heitmann has received funding from ‘MatPrat’, the information office for Norwegian egg and meat; L. Hvid is on the advisory board for Abbvie A/S; J. Fallingborg is on the advisory boards for AbbVie A/S, MSD Denmark, Takeda Pharma A/S, and Ferring Pharmaceuticals A/S; V. Andersen receives compensation for consultancy and for being a member of the advisory board for MSD Denmark (Merck) and Janssen A/S. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Written informed consent will be obtained from participants before participation in the study. The project has been approved by The Regional Scientific Ethical Committee (S-20160124) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (2008-58-035). The procedures followed are in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975 with later amendments.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Nielsen OH, Ainsworth MA. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med 2013;369:754–62. 10.1056/NEJMct1209614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumgart DC, Carding SR. Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology. Lancet 2007;369:1627–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60750-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet 2007;369:1641–57. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60751-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strober W, Fuss I, Mannon P. The fundamental basis of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Invest 2007;117:514–21. 10.1172/JCI30587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taurog JD, Chhabra A, Colbert RA, et al. Ankylosing Spondylitis and Axial Spondyloarthritis. N Engl J Med 2016;374:2563–74. 10.1056/NEJMra1406182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology 2012;142:46–54. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO. Chronic diseases and health promotion. 2017. http://www.who.int/chp/topics/rheumatic/en/

- 8.Poddubnyy D, Rudwaleit M. Efficacy and safety of adalimumab treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis and psoriatic arthritis. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2011;10:655–73. 10.1517/14740338.2011.581661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D, et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1316–22. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:377–85. 10.1038/jid.2012.339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan GG. The global burden of IBD: from 2015 to 2025. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;12:720–7. 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott DL, Wolfe F, Huizinga TW. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2010;376:1094–108. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60826-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lettre G, Rioux JD. Autoimmune diseases: insights from genome-wide association studies. Hum Mol Genet 2008;17:R116–R121. 10.1093/hmg/ddn246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellinghaus D, Jostins L, Spain SL, et al. Analysis of five chronic inflammatory diseases identifies 27 new associations and highlights disease-specific patterns at shared loci. Nat Genet 2016;48:510–8. 10.1038/ng.3528 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yadav P, Ellinghaus D, Rémy G, et al. Genetic factors interact with tobacco smoke to modify risk for inflammatory bowel disease in humans and mice. Gastroenterology 2017;153:550–65. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu JZ, van Sommeren S, Huang H, et al. Association analyses identify 38 susceptibility loci for inflammatory bowel disease and highlight shared genetic risk across populations. Nat Genet 2015;47:979–86. 10.1038/ng.3359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cortes A, Hadler J, Pointon JP, et al. Identification of multiple risk variants for ankylosing spondylitis through high-density genotyping of immune-related loci. Nat Genet 2013;45:730–8. 10.1038/ng.2667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bowes J, Budu-Aggrey A, Huffmeier U, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related susceptibility loci reveals new insights into the genetics of psoriatic arthritis. Nat Commun 2015;6:6046 10.1038/ncomms7046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Okada Y, Wu D, Trynka G, et al. Genetics of rheumatoid arthritis contributes to biology and drug discovery. Nature 2014;506:376–81. 10.1038/nature12873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tsoi LC, Spain SL, Knight J, et al. Identification of 15 new psoriasis susceptibility locihighlights the role of innate immunity.Nat Genet 2012;44:1341–8. 10.1038/ng.2467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Higuchi LM, et al. Higher predicted vitamin D status is associated with reduced risk of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2012;142:482–9. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.11.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Konijeti GG, et al. Long-term intake of dietary fat and risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut 2014;63:776–84. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Konijeti GG, et al. A prospective study of long-term intake of dietary fiber and risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2013;145:970–7. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Song M, et al. Zinc intake and risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: a prospective cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:1995–2005. 10.1093/ije/dyv301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ananthakrishnan AN, Khalili H, Song M, et al. High school diet and risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:2311–9. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chan SS, Luben R, Olsen A, et al. Association between high dietary intake of the n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid and reduced risk of Crohn’s disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:834–42. 10.1111/apt.12670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chan SS, Luben R, Olsen A, et al. Body mass index and the risk for Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: data from a European Prospective Cohort Study (The IBD in EPIC Study). Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:575–82. 10.1038/ajg.2012.453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan SS, Luben R, van Schaik F, et al. Carbohydrate intake in the etiology of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:2013–21. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.John S, Luben R, Shrestha SS, et al. Dietary n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and the aetiology of ulcerative colitis: a UK prospective cohort study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;22:602–6. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283352d05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Silva PS, Luben R, Shrestha SS, et al. Dietary arachidonic and oleic acid intake in ulcerative colitis etiology: a prospective cohort study using 7-day food diaries. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26:11–18. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328365c372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Silva PS, Olsen A, Christensen J, et al. An association between dietary arachidonic acid, measured in adipose tissue, and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology 2010;139:1912–7. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.07.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hart AR, Luben R, Olsen A, et al. Diet in the aetiology of ulcerative colitis: a European prospective cohort study. Digestion 2008;77:57–64. 10.1159/000121412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Opstelten JL, Leenders M, Dik VK, et al. Dairy products, dietary calcium, and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: results from a european prospective cohort investigation. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:S462 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lahiri M, Luben RN, Morgan C, et al. Using lifestyle factors to identify individuals at higher risk of inflammatory polyarthritis (results from the European Prospective Investigation of Cancer-Norfolk and the Norfolk Arthritis Register--the EPIC-2-NOAR Study). Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:219–26. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pattison DJ, Symmons DP, Lunt M, et al. Dietary risk factors for the development of inflammatory polyarthritis: evidence for a role of high level of red meat consumption. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:3804–12. 10.1002/art.20731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lund H, Brunnhuber K, Juhl C, et al. Towards evidence based research. BMJ 2016;355:i5440 10.1136/bmj.i5440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen V, Hansen AK, Heitmann BL. Potential impact of diet on treatment effect from anti-TNF drugs in inflammatory bowel disease. Nutrients 2017;9:286 10.3390/nu9030286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Heatley RV. Nutritional replenishment as an alternative to TNF-alpha in Crohn’s disease. Lancet 1997;349:1702 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62678-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee D, Baldassano RN, Otley AR, et al. Comparative effectiveness of nutritional and biological therapy in north american children with active crohn’s isease. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2015;21:1786–93. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Andersen V, Holmskov U, Sørensen SB, et al. A proposal for a study on treatment selection and lifestyle recommendations in chronic inflammatory diseases: a Danish multidisciplinary collaboration on prognostic factors and personalised medicine. Nutrients 2017;9:499 10.3390/nu9050499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.RADS. Rådet for Anvendelse af Dyr Sygehusmedicin. 2017. http://www.rads.dk/ (accessed 20.2.2017).

- 42.Ali FM, Johns N, Finlay AY, et al. Comparison of the paper-based and electronic versions of the Dermatology Life Quality Index: evidence of equivalence. Br J Dermatol 2017. (published Online First: 2017/01/24). 10.1111/bjd.15314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Campbell N, Ali F, Finlay AY, et al. Equivalence of electronic and paper-based patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res 2015;24:1949–61. 10.1007/s11136-015-0937-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khanna R, Bressler B, Levesque BG, et al. Early combined immunosuppression for the management of Crohn’s disease (REACT): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:1825–34. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00068-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vermeire S, O’Byrne S, Keir M, et al. Etrolizumab as induction therapy for ulcerative colitis: a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2014;384:309–18. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60661-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor PC, Keystone EC, van der Heijde D, et al. Baricitinib versus placebo or adalimumab in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med 2017;376:652–62. 10.1056/NEJMoa1608345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2534–48. 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sieper J, Rudwaleit M, Baraliakos X, et al. The assessment of spondyloarthritis international society (ASAS) handbook: a guide to assess spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68(Suppl 2):ii1–ii44. 10.1136/ard.2008.104018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mease PJ, McInnes IB, Kirkham B, et al. Secukinumab Inhibition of Interleukin-17A in Patients with Psoriatic Arthritis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1329–39. 10.1056/NEJMoa1412679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lebwohl M, Strober B, Menter A, et al. Phase 3 studies comparing brodalumab with ustekinumab in psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2015;373:1318–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1503824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimball AB, Okun MM, Williams DA, et al. Two Phase 3 Trials of Adalimumab for Hidradenitis Suppurativa. N Engl J Med 2016;375:422–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jaffe GJ, Dick AD, Brézin AP, et al. Adalimumab in patients with active noninfectious uveitis. N Engl J Med 2016;375:932–43. 10.1056/NEJMoa1509852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (stride): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1324–38. 10.1038/ajg.2015.233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.OPEN. 2017. http://www.sdu.dk/en/Om_SDU/Institutter_centre/Klinisk_institut/Forskning/Forskningsenheder/open.aspx (accessed 20 Febraury 2017).

- 55.Drosos GI, Pozo JL. The causes and mechanisms of meniscal injuries in the sporting and non-sporting environment in an unselected population. Knee 2004;11:143–9. 10.1016/S0968-0160(03)00105-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hemingway H, Croft P, Perel P, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 1: a framework for researching clinical outcomes. BMJ 2013;346:e5595 10.1136/bmj.e5595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Altman DG, Royston P. What do we mean by validating a prognostic model? Stat Med 2000;19:453–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.White IR, Horton NJ, Carpenter J, et al. Strategy for intention to treat analysis in randomised trials with missing outcome data. BMJ 2011;342:d40 10.1136/bmj.d40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Racine A, Carbonnel F, Chan SS, et al. Dietary patterns and risk of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: Results from the EPIC Study. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016;22:345–54. 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. European prospective investigastion into cancer and nutrition EPIC. 2014. http://epic.iarc.fr/

- 61.Togo P, Heitmann BL, Sørensen TI, et al. Consistency of food intake factors by different dietary assessment methods and population groups. Br J Nutr 2003;90:667–78. 10.1079/BJN2003943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tjønneland A, Overvad K, Haraldsdóttir J, et al. Validation of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire developed in Denmark. Int J Epidemiol 1991;20:906–12. 10.1093/ije/20.4.906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Køster-Rasmussen R, Siersma V, Halldorsson TI, et al. Missing portion sizes in FFQ--alternatives to use of standard portions. Public Health Nutr 2015;18:1914–21. 10.1017/S1368980014002389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tjonneland A, Haraldsdóttir J, Overvad K, et al. Influence of individually estimated portion size data on the validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Int J Epidemiol 1992;21:770–7. 10.1093/ije/21.4.770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Heitmann BL, Lissner L. Dietary underreporting by obese individuals: is it specific or non-specific? BMJ 1995;311:986–9. 10.1136/bmj.311.7011.986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Osler M, Heitmann BL. The validity of a short food frequency questionnaire and its ability to measure changes in food intake: a longitudinal study. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:1023–9. 10.1093/ije/25.5.1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.de Wit MP, Berlo SE, Aanerud GJ, et al. European league against rheumatism recommendations for the inclusion of patient representatives in scientific projects. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:722–6. 10.1136/ard.2010.135129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kappelman MD, Long MD, Martin C, et al. Evaluation of the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system in a large cohort of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:1315–23. 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.10.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Cheung PP, de Wit M, Bingham CO, et al. Recommendations for the involvement of patient research partners (PRP) in OMERACT working groups. A report from the OMERACT 2014 working group on PRP. J Rheumatol 2016;43:187–93. 10.3899/jrheum.141011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Steyerberg EW, Moons KG, van der Windt DA, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 3: Prognostic model research. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001381 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Riley RD, Hayden JA, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 2: Prognostic factor research. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001380 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hingorani AD, Windt DA, Riley RD, et al. Prognosis research strategy (PROGRESS) 4: stratified medicine research. BMJ 2013;346:e5793 10.1136/bmj.e5793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Osler M, Linneberg A, Glümer C, et al. The cohorts at the Research Centre for Prevention and Health, formerly ’The Glostrup Population Studies'. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:602–10. 10.1093/ije/dyq041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tjønneland A, Olsen A, Boll K, et al. Study design, exposure variables, and socioeconomic determinants of participation in Diet, Cancer and Health: a population-based prospective cohort study of 57,053 men and women in Denmark. Scand J Public Health 2007;35:432–41. 10.1080/14034940601047986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Desai MS, Seekatz AM, Koropatkin NM, et al. A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell 2016;167:1339–53. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Png CW, Lindén SK, Gilshenan KS, et al. Mucolytic bacteria with increased prevalence in IBD mucosa augment in vitro utilization of mucin by other bacteria. Am J Gastroenterol 2010;105:2420–8. 10.1038/ajg.2010.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gibson GR, Macfarlane GT, Cummings JH. Sulphate reducing bacteria and hydrogen metabolism in the human large intestine. Gut 1993;34:437–9. 10.1136/gut.34.4.437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Windey K, De Preter V, Louat T, et al. Modulation of protein fermentation does not affect fecal water toxicity: a randomized cross-over study in healthy subjects. PLoS One 2012;7:e52387 10.1371/journal.pone.0052387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yao CK, Muir JG, Gibson PR. Review article: insights into colonic protein fermentation, its modulation and potential health implications. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;43:181–96. 10.1111/apt.13456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ijssennagger N, van der Meer R, van Mil SW. Sulfide as a mucus barrier-breaker in inflammatory bowel disease? Trends Mol Med 2016;22:190–9. 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease. Nature 2011;474:298–306. 10.1038/nature10208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Cui J, Chen Y, Wang HY, et al. Mechanisms and pathways of innate immune activation and regulation in health and cancer. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014;10:3270–85. 10.4161/21645515.2014.979640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jia W, Whitehead RN, Griffiths L, et al. Diversity and distribution of sulphate-reducing bacteria in human faeces from healthy subjects and patients with inflammatory bowel disease. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2012;65:55–68. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2012.00935.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sundström B, Johansson I, Rantapää-Dahlqvist S. Diet and alcohol as risk factors for rheumatoid arthritis: a nested case-control study. Rheumatol Int 2015;35:533–9. 10.1007/s00296-014-3185-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Pearce MS, et al. Influence of dietary factors on the clinical course of ulcerative colitis: a prospective cohort study. Gut 2004;53:1479–84. 10.1136/gut.2003.024828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kelly KR, Haus JM, Solomon TP, et al. A low-glycemic index diet and exercise intervention reduces TNF(alpha) in isolated mononuclear cells of older, obese adults. J Nutr 2011;141:1089–94. 10.3945/jn.111.139964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Merga Y, Campbell BJ, Rhodes JM. Mucosal barrier, bacteria and inflammatory bowel disease: possibilities for therapy. Dig Dis 2014;32:475–83. 10.1159/000358156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hedrick VE, Dietrich AM, Estabrooks PA, et al. Dietary biomarkers: advances, limitations and future directions. Nutr J 2012;11:109 10.1186/1475-2891-11-109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Corella D, Ordovás JM. Biomarkers: background, classification and guidelines for applications in nutritional epidemiology. Nutr Hosp 2015;31(Suppl 3):177–88. 10.3305/nh.2015.31.sup3.8765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Holen T, Norheim F, Gundersen TE, et al. Biomarkers for nutrient intake with focus on alternative sampling techniques. Genes Nutr 2016;11:12 10.1186/s12263-016-0527-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang Y, Schöttker B, Florath I, et al. Smoking-associated DNA methylation biomarkers and their predictive value for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality. Environ Health Perspect 2016;124:67–74. 10.1289/ehp.1409020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Garneau V, Rudkowska I, Paradis AM, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids status in human subjects estimated using a food frequency questionnaire and plasma phospholipids levels. Nutr J 2012;11:46 10.1186/1475-2891-11-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Warensjö Lemming E, Nälsén C, Becker W, et al. Relative validation of the dietary intake of fatty acids among adults in the swedish national dietary survey using plasma phospholipid fatty acid composition. J Nutr Sci 2015;4:e25 10.1017/jns.2015.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wallingford SC, Pilkington SM, Massey KA, et al. Three-way assessment of long-chain n-3 PUFA nutrition: by questionnaire and matched blood and skin samples. Br J Nutr 2013;109:701–8. 10.1017/S0007114512001997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dragsted LO. Biomarkers of meat intake and the application of nutrigenomics. Meat Sci 2010;84:301–7. 10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.08.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Risérus U, Marklund M. Milk fat biomarkers and cardiometabolic disease. Curr Opin Lipidol 2017;28:46–51. 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Johnsen NF, Hausner H, Olsen A, et al. Intake of whole grains and vegetables determines the plasma enterolactone concentration of Danish women. J Nutr 2004;134:2691–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nørskov NP, Kyrø C, Olsen A, et al. High-throughput lc-ms/ms method for direct quantification of glucuronidated, sulfated, and free enterolactone in human plasma. J Proteome Res 2016;15:1051–8. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.5b01117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Moreno ML, Cebolla Á, Muñoz-Suano A, et al. Detection of gluten immunogenic peptides in the urine of patients with coeliac disease reveals transgressions in the gluten-free diet and incomplete mucosal healing. Gut 2017;66:250–7. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zamora-Ros R, Touillaud M, Rothwell JA, et al. Measuring exposure to the polyphenol metabolome in observational epidemiologic studies: current tools and applications and their limits. Am J Clin Nutr 2014;100:11–26. 10.3945/ajcn.113.077743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Krogholm KS, Bredsdorff L, Alinia S, et al. Free fruit at workplace intervention increases total fruit intake: a validation study using 24 h dietary recall and urinary flavonoid excretion. Eur J Clin Nutr 2010;64:1222–8. 10.1038/ejcn.2010.130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Linseisen J, Rohrmann S. Biomarkers of dietary intake of flavonoids and phenolic acids for studying diet-cancer relationship in humans. Eur J Nutr 2008;47(Suppl 2):60–8. 10.1007/s00394-008-2007-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Brantsaeter AL, Haugen M, Rasmussen SE, et al. Urine flavonoids and plasma carotenoids in the validation of fruit, vegetable and tea intake during pregnancy in the Norwegian Mother and Child Cohort Study (MoBa). Public Health Nutr 2007;10:838–47. 10.1017/S1368980007339037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Neale EP, Batterham MJ, Tapsell LC. Consumption of a healthy dietary pattern results in significant reductions in C-reactive protein levels in adults: a meta-analysis. Nutr Res 2016;36:391–401. 10.1016/j.nutres.2016.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Stedile N, Canuto R, Col CD, et al. Dietary total antioxidant capacity is associated with plasmatic antioxidant capacity, nutrient intake and lipid and DNA damage in healthy women. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2016;67:479–88. 10.3109/09637486.2016.1164670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Shah RV, Murthy VL, Allison MA, et al. Diet and adipose tissue distributions: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2016;26:185–93. 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sotos-Prieto M, Bhupathiraju SN, Falcon LM, et al. Association between a healthy lifestyle score and inflammatory markers among puerto rican adults. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2016;26:178–84. 10.1016/j.numecd.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ko BJ, Park KH, Shin S, et al. Diet quality and diet patterns in relation to circulating cardiometabolic biomarkers. Clin Nutr 2016;35:484–90. 10.1016/j.clnu.2015.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Marques-Rocha JL, Milagro FI, Mansego ML, et al. LINE-1 methylation is positively associated with healthier lifestyle but inversely related to body fat mass in healthy young individuals. Epigenetics 2016;11:49–60. 10.1080/15592294.2015.1135286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Umoh FI, Kato I, Ren J, et al. Markers of systemic exposures to products of intestinal bacteria in a dietary intervention study. Eur J Nutr 2016;55:793–8. 10.1007/s00394-015-0900-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Loprinzi PD, Lee IM, Andersen RE, et al. Association of concurrent healthy eating and regular physical activity with cardiovascular disease risk factors in u.S. Youth. Am J Health Promot 2015;30:2–8. 10.4278/ajhp.140213-QUAN-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yu E, Rimm E, Qi L, et al. Diet, lifestyle, biomarkers, genetic factors, and risk of cardiovascular disease in the nurses' health studies. Am J Public Health 2016;106:1616–23. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Satija A, Bhupathiraju SN, Rimm EB, et al. Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002039 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ardisson Korat AV, Willett WC, Hu FB. Diet, lifestyle, and genetic risk factors for type 2 diabetes: a review from the Nurses' Health Study, Nurses' Health Study 2, and Health Professionals' Follow-up Study. Curr Nutr Rep 2014;3:345–54. 10.1007/s13668-014-0103-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Nettleton JA, Steffen LM, Palmas W, et al. Associations between microalbuminuria and animal foods, plant foods, and dietary patterns in the multiethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:1825–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Armstrong AW, Harskamp CT, Dhillon JS, et al. Psoriasis and smoking: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2014;170:304–14. 10.1111/bjd.12670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ibfelt EH, Jensen DV, Hetland ML. The Danish nationwide clinical register for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: DANBIO. Clin Epidemiol 2016;8:737–42. 10.2147/CLEP.S99490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Gniadecki R, Kragballe K, Dam TN, et al. Comparison of drug survival rates for adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Br J Dermatol 2011;164:1091–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Bek S, Nielsen JV, Bojesen AB, et al. Systematic review: genetic biomarkers associated with anti-TNF treatment response in inflammatory bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016;44:554–67. 10.1111/apt.13736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Moore HM, Kelly AB, Jewell SD, et al. Biospecimen reporting for improved study quality (BRISQ). JProteomeRes 2011;10:3429–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Betsou F, Lehmann S, Ashton G, et al. Standard preanalytical coding for biospecimens: defining the sample PREanalytical code. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2010;19:1004–11. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Armyra K, Kouris A, Markantoni V, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa treated with tetracycline in combination with colchicine: a prospective series of 20 patients. Int J Dermatol 2017;56:346–50. 10.1111/ijd.13428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Skoie IM, Dalen I, Ternowitz T, et al. Fatigue in psoriasis: a controlled study. Br J Dermatol 2017;177:505–12. 10.1111/bjd.15375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]