Abstract

Introduction

The quality of clinical practice guidelines (PGs) has not been evaluated in child and youth mental health (CYMH). To address this gap, we will: (1) conduct a systematic review (SR) to answer the question ‘among eligible PGs relevant to the prevention or treatment of CYMH conditions, which PGs meet criteria for minimum and high quality?’; (2) apply nominal group methods to create recommendations for how CYMH PG quality, completeness and usefulness can be strengthened.

Methods and analysis

SR: Potentially eligible PGs will be identified in 12 databases using a reproducible search strategy developed by a research librarian. Trained raters will: (1) apply prespecified criteria to identify eligible PGs relevant to depression, anxiety, suicidality, bipolar disorder, behaviour disorder (attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder) and substance use disorder; (2) extract descriptive data and (3) assess PG quality using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) tool. Scores on three AGREE II domains (rigour of development, stakeholder involvement, editorial independence) will designate PGs as minimum (≥50%) or high quality (≥70%). Nominal group: Four CYMH PG knowledge user groups (clinicians, mental health service planners, youth and adult family members) will participate in structured exercises derived using nominal group methods to generate recommendations to improve PG quality, completeness and usefulness.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics approval is not required. Study products will be disseminated as follows. A cross-platform website will house eligible CYMH PGs and their quality ratings. Twitter and Facebook tools will promote it to a wide variety of PG users. Data from Google Analytics, Twitonomy and Altmetrics will inform usage evaluation. Complementary educational workshops will be conducted for CYMH professionals. Print materials and journal articles will be produced.

PROSPERO registration number

Keywords: practice guidelines child, adolescent, mental health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This systematic review will provide currently unavailable information about which existing child and youth mental health (CYMH) practice guidelines (PGs) are trustworthy and should be used by clinicians, mental health service planners, youth and family members.

Our protocol adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols criteria.

Nominal group consensus exercises conducted with four different types of PG users will identify how the quality, completeness and usefulness of CYMH PGs can be strengthened.

The review cannot address barriers and facilitators of successful guideline implementation.

By focusing on diagnosable conditions, it is possible that some important preventive interventions may not be included.

Introduction

Effective interventions are increasingly available to assess, prevent and treat child and youth mental health (CYMH) problems.1 However, studies repeatedly show that many children and youth experiencing mental health difficulties may not benefit from these interventions. For example, even in resource-rich settings, only about 20%–30% of youth in need are able to obtain any CYMH care.2 Equally concerning are findings that suggest even when children and youth are able to access CYMH services, the quality of care received is uneven at best, with wide variation in the types of services delivered within a single jurisdiction.3–6 Clinical practice guidelines (PGs) are decision aids that have the potential to help strengthen the quality of CYMH care and improve CYMH outcomes.7 The recommendations contained in high-quality PGs consist of statements about the comparative benefits and risks of different intervention options, systematically derived using rigorous critical appraisal and research synthesis methodologies. These statements can guide clinical decisions and mental health service planning, reduce variation in the services delivered and facilitate informed decision-making by youth experiencing mental health difficulties and their family members.7–9 Numerous CYMH PGs are now available, and leading national and international organisations regularly call for their increased production and use.10 11

The availability of high-quality, ‘trustworthy’ PGs is a non-negotiable prerequisite to promoting their development and use.7 Otherwise, PG implementation may not improve the quality of CYMH care, resulting in little or no mental health benefit to children and youth, and potentially increasing the risk of harm and wasted resources due to the implementation of flawed PG recommendations. PG quality has received considerable attention, particularly in internal medicine and its subspecialties.12–14 International criteria have been developed to guide the production of rigorous, clinically trustworthy PGs,7 and the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) tool,15–17 derived from these standards, has been used to appraise and improve PG quality relevant to adult chronic disease and to enable PG users to choose PGs based on quality. More recently, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) has proposed eight similar PG quality standards,18 and work has begun to translate them into a new tool for appraising quality/clinical validity.19

In contrast, to date, very little attention has been given to the quality of PGs relevant to CYMH conditions.20 The need to fill this gap is long overdue. We need to know which available CYMH PGs are trustworthy, and how to design initiatives to strengthen the capacity of the CYMH field to produce high-quality, useful PGs. As a first step, we appraised the rigour of the development methods currently used by groups who create CYMH PGs.20 Five different sets of development methods were identified within 70 individual CYMH PGs. Evaluation of these sets of development methods using both the AGREE II and IOM criteria revealed that roughly 70% of CYMH PGs may not be trustworthy because the methods used to develop them are weak, pointing to the urgent need to evaluate the quality of the actual CYMH PGs. The protocol reported below addresses this need and will proceed in three phases. First, a systematic review (SR) will be conducted to answer the question ‘Among eligible PGs relevant to the assessment, prevention or treatment of common CYMH conditions, which PGs meet criteria for minimum and high quality?’. The goal is to increase PG user awareness of specific trustworthy CYMH PGs by identifying all available CYMH PGs and determining which ones meet criteria for minimum and high-quality standards using the AGREE II appraisal tool. Second, working with four PG knowledge user (KU) groups (ie, clinicians, mental health service planners, youth and adult family members), nominal group methods will be employed to develop recommendations to guide improvements in CYMH PG quality, completeness and usefulness. The goal is to provide consensus-based statements that can inform capacity-building initiatives including how to strengthen CYMH PG quality through increased attention to rigorous develop methods, the identification of a core set of CYMH PGs, how to improve user skills relevant to choosing PGs based on quality, how to increase the alignment of PG content with different KU group needs and how to coordinate the work of different PG development groups so that PG quality is strengthened through increased efficiency and collaboration. Finally, a set of dissemination activities will be undertaken to make the results of this work widely available to both PG users and developers.

Methods and analysis

SR methods

Our methods adhere to Cochrane Collaboration21 and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Protocols standards.22 23

Research question

Among eligible PGs relevant to the assessment, prevention or treatment of common CYMH conditions, which PGs meet criteria for minimum and high quality?

Eligibility criteria

Documents identified using the search strategy described below will be deemed eligible if they meet the following criteria: (1) English language; (2) documents labelled PG, practice parameter or consensus or expert committee recommendations, or documents with the explicit objective or methods to develop original guidance/recommendations; (3) published, revised, updated or reaffirmed between 2005 and 2017; (4) address the assessment, prevention or treatment of one of the following CYMH disorder groups (as defined by Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition),24 mood (major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder), anxiety (agoraphobia, generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder), self-harm/suicidality, disruptive behaviour (attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder) and substance use disorders and (5) relevant to children and youth ≤18 years of age. Documents meeting the foregoing inclusion criteria will be excluded if judged to be a narrative or systematic literature review that contains summary statements regarding clinical implications/recommendations.

Information sources

Following advice from an experienced health research librarian (MR), we will search Medline, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL. Our grey literature search will include PG-specific sites (ie, National Guideline Clearinghouse, Canadian Medical Association Infobase, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Guidelines International Network International Guideline Library, Australia’s Clinical Practice Guidelines Portal and New Zealand Guidelines Group). It will also target mental health-related organisations (eg, American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry; Canadian Mental Health Association) and include a broad search using Google. All searches will be supplemented by screening reference lists of eligible PGs, using cited reference searching to reference forward eligible PGs, hand-searching key journals and soliciting recommendations from team members.

Search strategy

Our research librarian will use a strategy that combines subject heading and text terms for mental health AND guidelines AND children/adolescents. The strategy will be developed in Medline and then translated to terms appropriate to other databases and peer reviewed.25 A draft search strategy is provided in online supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2017-018053supp001.pdf (120.1KB, pdf)

Information management

Search results will be stored using bibliographic management software.

Selection process

One methodologist with expertise in the identification and quality assessment of PGs will independently screen the titles and abstracts of all unduplicated identified records using Reference Manager software. Only documents that clearly do not meet our inclusion criteria will be excluded at this stage, for example, title and/or abstract unambiguously indicates that the document: (1) is specific to adults; (2) does not address one or more of the target CYMH disorders or (3) publication date is prior to 2005. All remaining documents will proceed to full-text screening by two reviewers. A research assistant will obtain full-text records for all potentially relevant documents identified during title and abstract screening. Then two methodologists working independently will apply the inclusion criteria to full-text documents to identify eligible PGs. Disagreements regarding eligibility are then identified and resolved through discussion with the principal investigator (PI).

Data items and collection process

A trained research staff member will extract descriptive data for each eligible PG using a standardised form to capture: date produced; author; organisation type (government, medical society, special group, other); country of origin; CYMH disorder; target population (children and youth only; children, youth and adults); guideline purpose (assessment, prevention, treatment). Training will include refinement of item rewording as needed to improve clarity.

PG quality assessment methods, raters, training

PG quality ratings will be conducted using AGREE II.17 This validated tool is used widely and consists of 23 questions grouped in six domains: scope and purpose, stakeholder involvement, rigour of development, clarity of presentation, applicability, editorial independence. Two additional items assess overall quality. Item response options range from 1 to 7. Two reviewers (MSc in research methods) will participate in a three-stage training exercise: completion of the online AGREE II Overview Tutorial,26 a detailed review of the AGREE II User’s Manual17 and an online practice assessment of an example PG.27 Reviewers will meet with the PI to review disagreements and ‘lessons learned’ about AGREE II. Following training, the two reviewers will independently apply AGREE II criteria to eligible PGs using the My AGREE PLUS online platform.28 For each item, reviewers will indicate their score and justify it by recording document page and paragraph numbers for the information supporting each item in the comment box. When applying AGREE II criteria, reviewers will ensure that any companion documents for a given PG (eg, tools and resources to aid PG implementation, technical reports, health economic analyses, PG evaluation tools, etc, referenced in the main document) were considered in addition to the main PG document. Once the two raters have completed their independent AGREE II ratings, inter-rater differences ≥2 points on initial item scores will be identified and discussed by the two raters and the PI. This cut-point has been chosen as it is both pragmatic and conservative with respect to capturing scoring differences that arise from misinformation (ie, guideline documents are often very long and detailed and it is possible that a reviewer may simply miss important information) rather than differences in judgement regarding the content of the guideline documentation. Following discussion, reviewers are asked to reconsider and possibly revise their item scores; however, numerical agreement on the score assigned for each AGREE II item is not required. Thus, scoring differences that occur due to missed information in the documentation should be resolved during the discussion of disagreements. Any differences that remain following discussion should represent between rater differences in judgement (rather than failure to detect specific pieces of information within PG documents). Final item scores will then be aggregated into six domain scores by summing both reviewers’ scores for all items within a given domain and standardising as a percentage of the maximum possible score (ranging from 0% to 100%) using the formula described in the AGREE II User’s Manual.17

PG high-quality and minimum-quality rating criteria

The AGREE II User’s Manual does not provide criteria to designate PGs as high or low quality. Thus, the interpretation of domain scores and overall PG quality assessments are determined by the user. We will use scores on three AGREE II domains—stakeholder involvement, rigour of development (ie, rigorous consideration of the relevant research evidence base) and editorial independence (management of academic and financial conflict of interest)—to classify PGs according to quality. Minimum-quality PGs will be defined as those that receive a domain score ≥50% on all three domains. High-quality PGs will be defined as those that obtain a domain score ≥70% on all three domains. We selected these three domains because they address the extent to which risk of bias is minimised in the identification and interpretation of the research evidence used to derive the guideline recommendations. The remaining three domains, although important, do not evaluate the clinical validity and trustworthiness of the PG; rather they focus on the problem statement, clarity of presentation and implementability.

Data synthesis and statistical techniques

PG characteristics

Descriptive statistics (means, proportions) will be used to summarise eligible PG characteristics.

Rater agreement for AGREE II scores

We will calculate the intraclass correlation coefficient to assess inter-rater agreement29 and use Fleiss’ categories to classify the level of agreement: poor (0–0.40), fair to good (0.41–0.75) and excellent (>0.75).30 SPSS V.23 will be used to perform the statistical analyses.

Guideline quality

To answer our SR research question, each eligible PG will be classified as high quality or minimum quality using the AGREE II methods and classification criteria described above. The remaining individual domain scores for each PG will be reported for descriptive purposes. Our narrative summary will address the extent to which guidelines deemed high quality and minimum quality also perform well on the other three domains (ie, achieve our score cut-offs for minimum and high quality).

The six domain scores and overall guideline quality scores will also be used to describe the overall quality of CYMH guidelines. More specifically, mean domain scores and mean overall guideline quality scores for each disorder group will be calculated, and a narrative synthesis of guideline methodological strengths and weaknesses will be conducted.

The mean domain scores and overall scores for each guideline will also be grouped by source developer (eg, government agency, specialty society, independent expert group or other) to explore descriptively the extent to which each of these groups are more or less likely to produce high-quality guidelines than other groups. Again, narrative synthesis methods will be used to summarise these findings.

Nominal group methods

Research question: How can the quality and usefulness of PGs for CYMH disorders be strengthened?

To develop recommendations to guide future CYMH PG development, we will convene four CYMH PG KU groups, namely clinicians, mental health service planners and youth and adult family members, and engage them in a series of structured exercises derived using nominal group methods and the findings of the SR.31 32

Recommendation Development Group (RDG) membership

Group membership influences the outcomes of consensus exercises. Heterogeneous groups representing the range of relevant perspectives are preferred as they are more likely to produce judgements that reflect a conservative or middle ground.7 33 Accordingly, for each PG user group, we will form groups composed of 10 individuals. Clinicians and mental health service planners will be identified through nominations by project team investigators. Youth (aged 8 to 18 years) and adult family members will be nominated by the members of our youth and adult family member advisory committee and involvement to date in protocol development). Once the four groups are assembled, members will be asked if important viewpoints are not represented, and additional members (up to three) will be invited to participate as needed.

Managing conflict of interest

Methods consistent with current international standards will be used.34 Recommendation Development Group (RDG) participants will be asked to disclose financial or intellectual conflicts relevant to CYMH PG development. The project PI in consultation with other coinvestigators as needed will review all disclosed conflicts and make decisions regarding whether an individual should be recused from all or a portion of the recommendation development exercise.

Generating recommendations

A structured questionnaire, face-to-face meeting interactions and online rating derived from nominal group methods will be used.

Structured premeeting questionnaire

RDG members will respond to an electronic questionnaire prior to a face-to-face meeting. The content of the questionnaire will be derived from the findings of the SR and supported by relevant supplemental information. Provisional questions include:

(1) (A) Using AGREE II as a framework and the SR findings, how should minimum quality standards for CYMH PGs be defined?; (B) Based on the results of the SR, what methodological quality criteria should be the focus of capacity-building initiatives designed to improve PG quality?; (2) What CYMH PGs constitute a core set (including a rationale based on prevalence and burden of illness)?; (3) What content and PG development processes are needed to ensure that PGs are useful to specific types of KUs: (A) clinicians (child psychiatrists, family physicians, paediatricians, nurses, psychologists and social workers); (B) mental health service planners in provincial government ministries, hospitals and community agencies; (C) children and youth and (D) adult family members? and (4) How can increased collaboration between PG development groups be encouraged in order to strengthen PG quality and usefulness, and reduce duplication?

Each question will be linked to supplemental material based on SR findings and/or the content of the minimum-quality and high-quality PGs. For example, for question 1, the quality ratings for each PG (ie, domain scores) will be presented in tabular form. Each RDG participant will be asked to indicate whether each domain is relevant to defining minimum-quality standards, and if so, what score cut-point should be used? Similarly, participants will be asked to define high quality using the AGREE II domains. For provisional question 3 (What content and PG development processes are needed to ensure that PGs are useful to specific types of PG users?), each RDG participant will be provided with electronic access to supplementary materials (eg, template summary of PG content, template summary of PG development process, copy of actual PG) derived from the minimum-quality and high-quality PGs, and asked to identify specific aspects of the content and developmental processes that are essential and/or missing from their user perspective.

Face-to-face meeting

First, the SR findings and collated premeeting questionnaire results will be reviewed in a large group session. Then, each KU group will work independently in small groups with an expert facilitator who is not part of the research team to draft recommendations related to each premeeting question. The goal is to ensure that each PG user group has an equal voice, and that all individuals have the opportunity to express their views. Each small group will then report their draft recommendations for each question to the full group. The principal investigator will collate draft recommendations into a final provisional set for review in the final session of the day. The final set will include draft recommendations that are common to all four PG user groups and draft recommendations that are unique to a specific PG user group.

Generating final recommendations and quantifying the level of consensus

We will finalise the content of the recommendations drafted in the face-to-face meeting and quantify RDG member agreement (0% to 100%) for each recommendation as follows. First, 48 hours after the face-to-face meeting, RDG members will indicate their level of agreement with each draft recommendation using a 7-point scale (1=strongly disagree; 7=strongly agree). Ratings will be collected anonymously in an online survey. RDG members will then be provided with a summary of scores, and participate in a conference call 1 week later to discuss and revise each recommendation as necessary. Finally, RDG members will re-rate their agreement with each revised recommendation in a second anonymous online exercise. Although consensus (ie, 100% agreement among RDG members on the rating assigned to a recommendation) may be achieved for a specific recommendation, this is not our aim. Quantifying the extent of variation in agreement/disagreement with the recommendations produced is an integral part of accurate communication of RDG views.7

Youth and family member participation in protocol development and preparation prior to project start-up

Informed by patient and public involvement methodology, we have already convened a youth and adult family member advisory group (four youth, two adult family members) to provide leadership throughout the project.9 During proposal development, this group first planned the type of involvement they wished to have in the project using the following ‘meaningful engagement’ continuum: consultation, involvement, partnership and shared leadership.35 36 The results of their deliberations are as follows. First, they will participate as learners in the SR to understand PGs and quality appraisal methods. Then, with this preparation, their goal in subsequent project stages will be participation/shared leadership (eg, develop recommendations for how PGs can be more acceptable/useful to youth and adult family members; create dissemination tools tailored to the needs of youth and adult family members). Specific processes and roles are aligned with engagement principles including reciprocal relationships, colearning, partnerships, transparency, honesty and trust.35 36

Training workshops for youth and family members

Four training workshops for youth and adult family members will be conducted prior to participating in the SR, structured nominal group exercises, face-to-face meeting, online survey and conference call. First, youth and adult family members will participate in three half-day workshops to learn about PGs and the AGREE II quality assessment process. The goal is to support capacity development and facilitate their engagement in the SR and recommendation development process. The first workshop will include a 1:1 orientation for each individual and a ‘Terms of Reference’ document will be codeveloped with the entire group. This document will capture the core engagement principals that guide our project and the continuum of meaningful engagement we are using (consultation, involvement, partnership and shared leadership). Workshop 1 will also address processes to support conflict resolution and clinical support.

A fourth workshop will be convened prior to the full team meeting focusing on recommendation development to: (1) prepare youth and adult family members for their role in generating recommendations relevant to PG acceptability/usefulness and (2) enable them to provide input into the full team meeting agenda to ensure a meaningful process that facilitates youth and adult family member engagement in the deliberations and decisions.

We will also conduct briefing sessions prior to and following each workshop, and provide ongoing support as appropriate to facilitate sustained engagement.

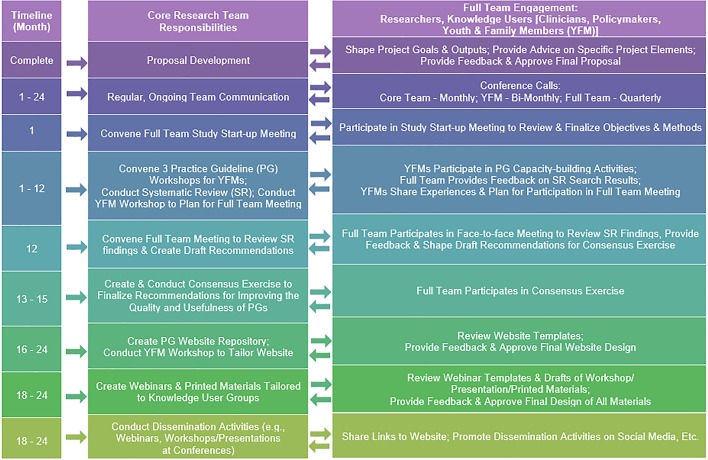

Integrated knowledge translation

Throughout the project, we will use integrated knowledge translation (iKT) methods to ensure our goals and outputs are relevant to the needs of our four KU user groups.37 Figure 1 illustrates how the core project team will interact with our full team of researchers and KUs to accomplish our iKT goals in each project stage.

Figure 1.

Team members will conduct their work over a 24-month period as described in the steps shown.

Potential challenges

Conflict of Interest: If not managed appropriately, conflict of interest could introduce bias into our work. We will address this risk as follows. First, AGREE II will be applied by MSc-level raters with no potential for intellectual or financial conflict of interest that might systematically bias ratings. Second, conflicts among RDG members will be declared and managed as described above. Number of PGs: Our pilot work shows that the number of PGs that meet our eligibility criteria can be rated with AGREE II in the timeline proposed (2 years). Team Member Engagement: All team members have reviewed our project activities and timeline and have provided written commitments to participate in project activities as shown in figure 1. Youth and Adult Family Member Engagement: This is an area of demonstrated expertise for one of our team members (PS). She has already convened our youth and adult family member advisory group and successfully engaged them in planning their involvement in each stage of the project.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethics

This SR and consensus exercise protocol is considered a quality improvement initiative and hence, does not require ethics approval.38

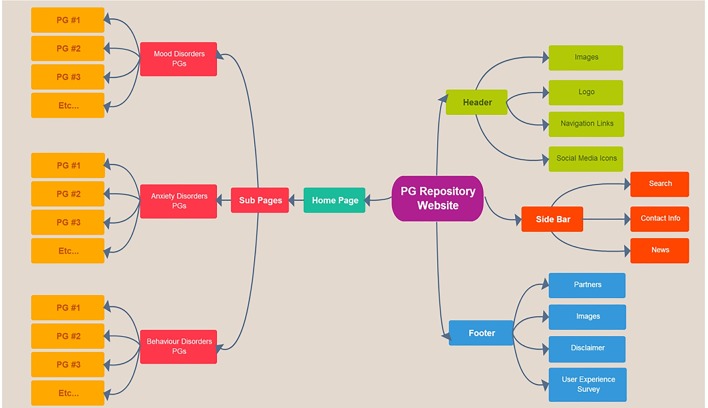

Web-based PG repository platform to disseminate quality-assessed PGs

A cross-platform (ie, desktop, tablet and smartphone accessible) website will be created including content tabs to facilitate navigation, a contact form for users to submit questions and a user experience survey to solicit feedback. Figure 2 presents website design elements.

Figure 2.

Our practice guideline (PG) repository website will be structured as shown providing access to quality-appraised guidelines organised by disorder.

Website promotion

To disseminate our findings and increase PG user knowledge of trustworthy CYMH PGs, we will launch a social media campaign to engage with the CYMH community using Twitter and Facebook, aiming for three posts per week. Posts will include PG content, links to PGs, project updates/summaries and news pieces. KUs will also be invited to promote our website through their Twitter accounts.

Evaluation

Data from Google Analytics,39 Twitonomy40 and Altmetric41 inform evaluation of website usage.

Youth and adult family member website workshop

A half-day workshop will be held to enable youth and family members to review website planning with our web/media expert and integrate youth and family member preferences and needs.

Webinar

Representatives of each of the four KU groups will participate in webinar development to ensure that it meets their needs and invite their members to participate in one of the four planned webinar offerings.

Manuscripts

At least two peer-reviewed open-access publications will be developed.

Written materials

Tailored project summaries, developed with input from our KU groups will be hosted on our website and shared with our KU partners.

Workshops

Workshops and presentations will be held at KU meetings (eg, PolicyWise for Children and Families event, Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry conference, Canadian Pediatric Society conference, College of Family Physicians of Canada Family Health Forum, Healthy Child Manitoba event, Ontario Centre of Excellence in Child and Youth Mental Health partners (eg, Parents for Children’s Mental Health; The New Mentality), Ontario Ministries (Children and Youth Services (MCYS), Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC), Education (EDU)).

Conclusion

Children and youth deserve the best possible mental health services. To this end, this synthesis, informed by user needs (clinicians, mental health service planners, youth, adult family members) will: advance knowledge by identifying trustworthy CYMH PGs and documenting the strengths and weaknesses of existing CYMH PGs; guide future PG development by formulating recommendations for how to improve CYMG PG quality, completeness and usefulness; and facilitate knowledge application by creating user-informed dissemination tools to promote the use of high-quality PGs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of our youth and adult family member advisory committee (S Cannon, Z Johnstone, L Langford, G Loucks, A Messaoudi and H Smith) for their contributions to proposal methods related to youth and adult family member engagement.

Footnotes

Contributors: KJB conceived the initial idea for the study and is the guarantor of the protocol. KJB and SD wrote the first draft of the protocol. KJB, SD, MB, PSz, AN, JM, PS, KC, AC, JH, DC and MR reviewed multiple versions of the protocol providing critical comment and further developing the methods. KJB, SD, MB, PSz, AN, JM, PS, KC, AC, JH, DC and MR read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work is supported in part by the Margaret and Wallace McCain Centre for Child, Youth & Family Mental Health, Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Toronto, Ontario. The funder had no role in developing or implementing the study protocol.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The findings from our systematic review and nominal group consensus exercises will be disseminated through a specially developed website. Additional information can be requested from the principal investigator.

References

- 1.Patel V, Flisher AJ, Hetrick S, et al. . Mental health of young people: a global public-health challenge. Lancet 2007;369:1302–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60368-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. . Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;50:32–45. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garland AF, Bickman L, Chorpita BF. Change what? Identifying quality improvement targets by investigating usual mental health care. Adm Policy Ment Health 2010;37(1-2):15–26. 10.1007/s10488-010-0279-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weisz JR, Sandler IN, Durlak JA, et al. . Promoting and protecting youth mental health through evidence-based prevention and treatment. Am Psychol 2005;60:628–48. 10.1037/0003-066X.60.6.628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chagnon F, Pouliot L, Malo C, et al. . Comparison of determinants of research knowledge utilization by practitioners and administrators in the field of child and family social services. Implement Sci 2010;5:41 10.1186/1748-5908-5-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoagwood K, Burns BJ, Weisz J. A profitable conjunction: from science to service in children’s mental health : Burns BJ, Hoagwood K, Community treatment for youth: Evidence-based interventions for severe emotional and behavioural disorders. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2002:327–38. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC National Academies Press, 2011. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Standards for Developing Trustworthy Clinical Practice Guidelines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vernooij RW, Willson M, Gagliardi AR. members of the Guidelines International Network Implementation Working Group. Characterizing patient-oriented tools that could be packaged with guidelines to promote self-management and guideline adoption: a meta-review. Implement Sci 2016;11:52 10.1186/s13012-016-0419-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Légaré F, Boivin A, van der Weijden T, et al. . Patient and public involvement in clinical practice guidelines: a knowledge synthesis of existing programs. Med Decis Making 2011;31:E45–74. 10.1177/0272989X11424401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mental Health Commission of Canada. Changing directions, changing lives: the mental health strategy for Canada. Calcary, AB: Author, 2012. http://strategy.mentalhealthcommission.ca/pdf/strategy-images-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. WHO handbook for guideline development. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaneyfelt TM, Mayo-Smith MF, Rothwangl J. Are guidelines following guidelines? The methodological quality of clinical practice guidelines in the peer-reviewed medical literature. JAMA 1999;281:1900–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alonso-Coello P, Irfan A, Solà I, et al. . The quality of clinical practice guidelines over the last two decades: a systematic review of guideline appraisal studies. Qual Saf Health Care 2010;19:e58 10.1136/qshc.2010.042077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kung J, Miller RR, Mackowiak PA. Failure of clinical practice guidelines to meet institute of medicine standards: Two more decades of little, if any, progress. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:1628–33. 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. . Development of the AGREE II, part 1: performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. CMAJ 2010;182:1045–52. 10.1503/cmaj.091714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. . Development of the AGREE II, part 2: assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ 2010;182:E472–8. 10.1503/cmaj.091716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agree Next Steps Consortium. AGREE-II user’s manual 2010-2014. 2013. http://www.agreetrust.org (accessed 06 Mar 2014).

- 18.Ransohoff DF, Pignone M, Sox HC. How to decide whether a clinical practice guideline is trustworthy. JAMA 2013;309:139–40. 10.1001/jama.2012.156703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.G-I-N 2016Scientific Committee. Developing and testing the National Guideline Clearinghouse extent adherence to trustworthy standards instrument [oral presentation]. 13th Guidelines International Network (G-I-N) Conference [program]. Pennsylvania, USA: G-I-N 2016 Scientific Committee, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett K, Gorman DA, Duda S, et al. . Practitioner Review: On the trustworthiness of clinical practice guidelines - a systematic review of the quality of methods used to develop guidelines in child and youth mental health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2016;57:662–73. 10.1111/jcpp.12547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higgins JPT, Se G. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. London, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006–12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shamseer L, Moher D, Clarke M, et al. . Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. BMJ 2015;349:g7647 10.1136/bmj.g7647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fifth Edition Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.CADTH. Peer review checklist for search strategies. Toronto, ON: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 26.The AGREE Research Trust. AGREE II overview tutorial 2010-2014. http://www.agreetrust.org/resource-centre/agree-ii-training-tools/ (accessed 01 May 2016).

- 27.The AGREE Research Trust. AGREE II tutorial + practice exercise 2010-2014. http://www.agreetrust.org/resource-centre/agree-ii-training-tools/ (accessed 01 May 2016).

- 28.The AGREE Research Trust. My agree plus 2010-2014. http://www.agreetrust.org/login/ (accessed 01 May 2016).

- 29.Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educ Psychol Meas 1973;33:613–9. 10.1177/001316447303300309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fleiss JL, Cohen J. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 2nd edn New York, NY: John Wiley, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995;311:376–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M, et al. . Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health 1984;74:979–83. 10.2105/AJPH.74.9.979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hutchings A, Raine R. A systematic review of factors affecting the judgments produced by formal consensus development methods in health care. J Health Serv Res Policy 2006;11:172–9. 10.1258/135581906777641659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schünemann HJ, Osborne M, Moss J, et al. . An official American Thoracic Society Policy statement: managing conflict of interest in professional societies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:564–80. 10.1164/rccm.200901-0126ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI). PCORI Engagement Rubric. 2014. http://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/Engagement-Rubric.pdf (accessed 02 Feb 2016).

- 36.Carman KL, Dardess P, Maurer M, et al. . Patient and family engagement: a framework for understanding the elements and developing interventions and policies. Health Aff 2013;32:223–31. 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CIHR. Guide to knowledge translation planning at CIHR: integrated and end-of-grant approaches. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), 2012. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/documents/kt_lm_ktplan-en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 38.Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Tri-Council Policy Statement. Ethical conduct for research involving humans. 2014. http://www.pre.ethics.gc.ca/pdf/eng/tcps2-2014/TCPS_2_FINAL_Web.pdf

- 39.Google. Google analytics. 2017. http://www.google.com/analytics (accessed 05 Dec 2015).

- 40.Diginomy Pty Ltd. Twitonomy. 2017. https://www.twitonomy.com/ (accessed 05 Dec 2015).

- 41.Altmetric. Altmetric. 2017. https://www.altmetric.com/ (accessed 05 Dec 2015).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-018053supp001.pdf (120.1KB, pdf)