Abstract

Introduction

The current literature in Australia demonstrates that there are variations in access and outcomes in perinatal care based on socioeconomic factors. However, little has been done looking at the level of out-of-pocket healthcare costs associated with perinatal care. The primary aim of this project will be to quantify health service use and out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure associated with childbearing and early childhood in Queensland, Australia.

Methods and analysis

This project will build Australia’s first model (called Maternal & Child Cost MOD) of out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure by using administrative data from the Queensland Perinatal Data Collection, of all childbearing women and their resultant children, who gave birth in Queensland between 1 July 2012 and 30 June 2016.

The current costs to the health system and out-of-pocket health care expenditure of patients associated with maternity and early childhood health care will be identified. The differences in costs based on indigenous identification, socioeconomic status and geographic location will be assessed using linear regression modelling and counterfactual modelling techniques.

Ethics and dissemination

Human Research Ethics approval has been obtained from Townsville Hospital and Health Service Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (HREC Reference number: HREC/16/QTHS/223). Consent will not be sought from participants whose de-identified data will be used in this study. Permission to waive consent has been gained from Queensland Health under the Public Health Act 2005.

The results of this study will be disseminated through publications in peer-reviewed journals and through presentations at conferences, regionally and nationally. Our target audience is clinicians, health professionals and health policy-makers.

Keywords: maternal and child health, health service use, inequities, patient costs

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study uses administrative data, which is not reliant on patient recall.

Captures data from all women who gave birth in the given time frame in Queensland, so not reliant on patient recruitment and thus avoids the introduction of bias from poor representation of certain, often at-risk groups.

Data obtained from one state in Australia.

Limited by the scope of administrative data collections, some costs may be excluded.

Introduction

Australia is known to be one of the safest countries in the world in which to give birth or to be born.1 Despite this, significant health disparities exist between different groups of Australians, including Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged, and people who reside in rural and remote locations.1 2 Rural and remote mothers, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mothers and socioeconomically disadvantaged women experience higher rates of maternal3 and neonatal4 mortality. This can result from problems in accessing necessary healthcare services.

Access to prenatal screening tests is lower for women living in rural and remote areas, those in the lowest quintile of the Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) and Aboriginal women.5 Data from Western Australia show that health services that provide antenatal screening are generally located in high socioeconomic areas and few are located in rural and remote areas.5 Supportive of this is a decreasing trend in Down syndrome birth rates for women residing in metropolitan areas or those who receive prenatal care from a private obstetrician. However, this decrease is not evident among women living in rural and remote areas or those who received prenatal care in a public hospital.6 Aboriginal women and those in rural or remote areas are less likely to attend their first antenatal visit during the first trimester of pregnancy and on average attend less antenatal appointments than non-Aboriginal women and women in metropolitan areas.7 8

A trend of population movement towards urban areas in Australia has seen a decline in the number of healthcare facilities that are able to provide perinatal care for women in rural and remote areas.1 Current maternal healthcare supports and services in Australia, including travel and communication, are insufficient for families living in rural and remote areas.9 Mothers and babies require access to an appropriately skilled workforce and necessary infrastructure, which are not available in all communities. An alternative to lengthy travel to access some aspects of maternal health services in Australia are fly-in fly-out services from maternal healthcare professionals.9 These services have been known to improve access for people who reside in rural or remote communities; however, there has been a decline in these services over recent years. Between 1995 and 2006, over 130 rural maternity units closed across Australia.10 Between 1991 and 2006, approximately one third of hospitals and birth centres shut down, with the greatest reduction experienced in communities that saw between 1 and 100 births per year.11 12 Families in rural and remote communities face disruption and costs associated with travel to access maternal health services, highlighting the need to better understand health service use and cost for mothers during the perinatal period. Inequality in health service provision creates barriers to accessing perinatal care, which is evident in the poorer health outcomes experienced by rural and remote mothers and babies.9 Antenatal care is associated with positive health outcomes for both the mother and baby and the likelihood of receiving effective health interventions is increased through antenatal attendance.13 Receiving such care during the perinatal period would improve health outcomes and ultimately lessen the health disparities experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged, and people who reside in rural and remote locations.9

Socioeconomically disadvantaged women have higher rates of obesity during pregnancy and are more likely to have pre-existing health conditions such as hypertension and diabetes.14 Obesity during pregnancy increases the risk of adverse perinatal outcomes including hyperglycaemia, caesarean delivery, intensive or special care nursery admission, resuscitation, macrosomia and death.14 Similarly, the groups of women that are more likely to smoke during pregnancy are those living in remote areas (37% compared with 9% in major cities), mothers in low socioeconomic position (20% compared with 4% in high socioeconomic position) and Aboriginal mothers (47% compared with 13% non-Aboriginal).7 Smoking during pregnancy is associated with poor perinatal health outcomes including preterm birth, low birth weight and perinatal death.7

A national study has found that women from the lowest socioeconomic group are twice as likely to suffer from severe maternal morbidity, including amniotic fluid embolism, antenatal pulmonary embolism, eclampsia, peripartum hysterectomy and placenta accreta compared with women who are in the highest socioeconomic group.15 Additionally, women who fall into the lower socioeconomic quintile are more likely to suffer from poor mental health during the perinatal period.16 There is emerging evidence that suggests a strong association between perceived discrimination at maternal healthcare facilities and poor perinatal outcomes. An Australian study found that women attending public maternity healthcare were more likely to have low socioeconomic characteristics and were more likely to report discrimination, compared with those attending private maternity healthcare.17

The current literature clearly demonstrates the variations in access and outcomes in perinatal care based on socioeconomic factors, rurality and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women. Recent research has highlighted that out-of-pocket costs may act as a barrier to accessing healthcare, with Callander et al estimating that one in four Australians skipping care due to the cost.18 While Callander et al also quantified the out-of-pocket costs of a number of chronic adult conditions, there has been no estimation in the peer-reviewed literature of the out-of-pocket costs associated with childbearing and early childhood.

Australia has universal healthcare, with a public health insurance system, Medicare. Medicare provides treatment free of charge in public hospitals and subsidies the cost of out-of-hospital treatment. The out-of-hospital treatment component of Medicare provides a rebate benefit for services, based on a proportion of a schedule of fees covering each type of service. For example, for a consultation with a general practitioner lasting 20 min or less, the schedule fee in 2017 is $37.05 the benefit being 100% of the schedule fee, or $37.05; an obstetric consultation has a schedule fee of $85.55, and the benefit is 75% of the schedule fee giving a rebate of $64.20. However, the actual charge for services is set by providers,19 and this is unregulated, meaning that providers are able to set their fees above the schedule fee. Any difference between the price providers charge for a service and the rebate amount is paid by patients ‘out of pocket’.

With the concern of a two-tiered health system evolving in Australia, those who do not have private health insurance, which is typically people in the lower socioeconomic bracket, may experience delays in accessing health services.20 Out-of-pocket healthcare costs in Australia are causing people to delay or forego their medical appointments18 21 and increasing the financial burden experienced by individuals, with the greatest financial strain experienced by those with lower incomes.21 The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) estimated in 2010–2011 $24.3 billion on healthcare expenditure came directly from the pockets of healthcare consumers, which is an annual average of $1082 per person. Recent healthcare reforms have been introduced with the intention to provide assistance with out-of-pocket healthcare payments; however, the evidence demonstrates that the benefits of such reforms are being experienced by higher income groups,22 leaving those who are socioeconomically disadvantaged disproportionately affected.

This project will build Australia’s first model of perinatal and child health service use based on administrative data—combining sources of hospital inpatient, out-of-hospital healthcare and prescription medication use on the one dataset. This dataset will allow us to identify the health system and out-of-pocket healthcare costs attributable to each occasion of use. Based on this, the researchers will be able to quantify the average out-of-pocket healthcare costs associated with perinatal and early childhood healthcare and look at different socioeconomic groups within Queensland.

Understanding the current level of out-of-pocket costs, and the differences in costs and access across different groups will allow (1) health policy makers to ensure that the Australian health systems are affordable and accessible to all population groups; and (2) clinicians and health professionals to be aware of the total out-of-pocket costs being paid by patients in their care.

Objectives

We propose to create a model of health service use and cost called Maternal & Child Cost MOD, which will include most direct out-of-pocket costs associated with childbearing and early childhood in Queensland. This will be Australia’s first model of healthcare use and expenditure of childbearing women and their resultant children using administrative data, linking records from Perinatal Data Collection, Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection (QHAPDC), Registrar General Deaths, Emergency Department Information System (EDIS), cost data held by the HHS Funding and Costing Unit, and Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) and Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) claim records. The aims of this study are

to identify health service use associated with childbearing and early childhood

to quantify the health system costs of childbearing and early childhood

to quantify out-of-pocket healthcare costs associated with childbearing and early childhood

to determine any inequalities in health service use and out-of-pocket costs between different subpopulations (including high and low socioeconomic status, rural and remote and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations).

Methods

Study setting

This project will use a census of patients from the Perinatal Data Collection (covering both mothers and babies) and thus will not be subject to recruitment bias. Being a census, it will be able to capture the expenditure of all mothers and their children in Queensland within the relevant time frames. Queensland is Australia’s third most populous state with a population of 4.9 million in 2015. In 2015, there were 61 745 babies born in Queensland, of which 5207 identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander.23 Queensland has a unique population in that it has a relatively large proportion of its population living outside major cities, and a relatively large proportion of its population identifying as Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander.24 Such populations have higher fertility rates and a relatively high risk of maternal medical complications,25 but can also be under-represented in national surveys.26 As such, Queensland-based data provide a unique opportunity to capture results from at-risk and under-represented populations, while providing results that can be generalised to the Australian population.

Data

Datasets and variables

This project will link the following administrative datasets:

Queensland Perinatal Data Collection: collects information on all births within Queensland for the purposes of obstetric and neonatal research and health service planning.

Data custodian: Executive Director, Statistical Services Branch, Queensland Health.

- Requested variables:

- place of delivery (hospital, birthing centre, home, other)

- date of admission (mm-yyyy)

- mother’s country of birth (broad country of birth categories)

- indigenous status (flag indigenous/non-indigenous)

- marital status

- accommodation status of mother

- year of birth (yyyy)

- postcode

- antenatal transfer

- reason for transfer

- transferred from (facility ID for public hospitals only or ‘private’)

- date of transfer (mm-yyyy)

- previous pregnancies flag

- total number of previous pregnancies

- methods of delivery of last birth

- number of previous caesareans

- smoking (smoking during the first 20 weeks of pregnancy, smoking after 20 weeks of pregnancy)

- date of last menstrual period

- estimated date of confinement

- height

- weight

- antenatal care status

- antenatal care type

- total number of antenatal visits

- gestation at first antenatal visit

- current medical conditions

- pregnancy complications

- procedures and operations

- number of ultrasound scans

- types of ultrasound scans (nuchal translucency scan, morphology scan, chronicity scan)

- assisted conception flag

- assisted conception methods

- intended place of birth at onset of labour (hospital, birthing centre, home, other)

- actual place of birth of baby (hospital, birthing centre, home, other)

- onset of labour

- methods used to induce labour or augment labour

- main reason for induction

- membranes ruptured

- length of first and second stage of labour

- presentation at birth

- method of birth

- water birth

- reason for forceps or vacuum

- main reason for caesarean

- non-pharmacological analgesia during labour/delivery

- pharmacological analgesia during labour/delivery

- labour and delivery complications

- anaesthesia for delivery

- Baby details

- date of birth (mm-yyyy)

- indigenous status (flag indigenous/non-indigenous)

- time of birth

- birth weight

- gestation

- head circumference at birth

- length at birth

- plurality

- sex

- birth status(born alive)

- one-minute APGAR score

- five-minute APGAR score

- regular respiration

- resuscitation flag

- Postnatal details

- neonatal morbidity

- neonatal treatment

- admitted to Intensive Care Nursery (ICN)/Special Care Nursery (SCN)

- main reason for admission to ICN/SCN

- congenital anomaly flag

- congenital anomaly ICD code(s)

- congenital anomaly location

- Discharge details

- puerperium complications

- thromboprophylaxis following caesarean—discharge details of mother: discharged OR transferred OR remained in hospital OR died

- discharge details of mother: date of discharge

- discharge details of baby: discharged OR transferred OR remained in hospital OR died

- discharge details of baby: date of discharge

- type of fluid baby received at any time from birth to discharge

- type of fluid baby received in the 24 hours prior to discharge

- alternative feeding method (all)

- Death Registration Data: It records all births within Queensland. Data custodian: Executive Director, Statistical Services Branch, Queensland Health; Requested variables

- date of death (mm-yyyy)

- Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection: It contains demographic and clinical information on all patients admitted to all Queensland public and private hospitals, and day surgery units. Data custodian: Executive Director, Statistical Services Branch, Queensland Health Requested variables

- admission date

- account class at admission

- chargeable status at admission

- source of referral/transfer

- transferring from facility (if public hospital, private hospitals to be returned as ‘private’)

- care type

- standard ward code at admission

- separation date (mm-yyyy)

- mode of separation (home, usual residence, transfer to another hospital, residential aged care, other healthcare establishment, died in hospital, episode change, discharged at own risk, non-return from leave, medi hotel, other)

- transferring to facility (public facility name only, if private facility then ‘private’)

- hospital insurance status

- funding source

- length of stay in intensive care unit

- principal diagnosis

- procedures

- Australian Refined Diagnostic Related Group (AR-DRG)

- major diagnostic category

- telehealth provider facility

- telehealth provider unit

- telehealth event types

- telehealth start date and time (mm-yyyy and hh:mm)

- telehealth end date and time (mm-yyyy and hh:mm);

- Emergency Department Information System: It provides data on care and treatment given to patients in Queensland emergency departments. Data custodian: Executive Director, Healthcare Improvement Unit, Queensland Health Requested variables

- facility number

- postcode

- triage category

- mode of arrival

- visit type

- discharge destination (if available)

- principal diagnosis

- additional diagnoses (up to two available)

- procedures (if available)

- investigations (if available);

- Clinical Costing Information: It records hospital costs, revenue and activity-based funding data at the patient level for Queensland public hospitals. Data custodian: Activity Costings Team, HHS Costing, and Funding Unit, Healthcare Purchasing and Funding Branch, Queensland Health Requested variables

- Cost for the occasion of service

Medicare Benefits Schedule claims records: It records details of every claim made to Medicare for items covered on the Medicare Benefits Schedule.

Data custodian: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

- Requested variables

- date of service

- Medicare item number

- provider charge

- patient out of pocket

- rendering provider postcode

- hospital indicator

- patient postcode

Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme claims records: It records details of every claim made to Medicare for items covered on the PBS.

Data custodian: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

- Requested variables

- date of supply

- PBS item code

- patient category

- patient contribution

- net benefit

- pharmacy postcode

- patient postcode.

Cohort identification and data extraction

The cohort will be composed of all babies born between 1 July 2012 and 30 June 2016 and their mothers. These individuals will be identified from the Queensland Perinatal Data Collection by the Statistical Services Branch (SSB), Queensland Health. The identifying information to be used for identifying information corresponding to the cohort from the remaining datasets will be obtained from the Queensland Perinatal Data Collection and the Birth Registration Data; these identifying variables will be mother’s name, mother’s date of birth, baby’s name, baby’s date of birth and mother’s address (figure 1). The identifying information will be removed before the data are returned to the researchers. A unique project identification number will be created for each mother and baby, plus a variable to identify the mother of each baby.

Figure 1.

Variables used to identify cohort (shown in red), and identifiers provided to researchers (shown in green).

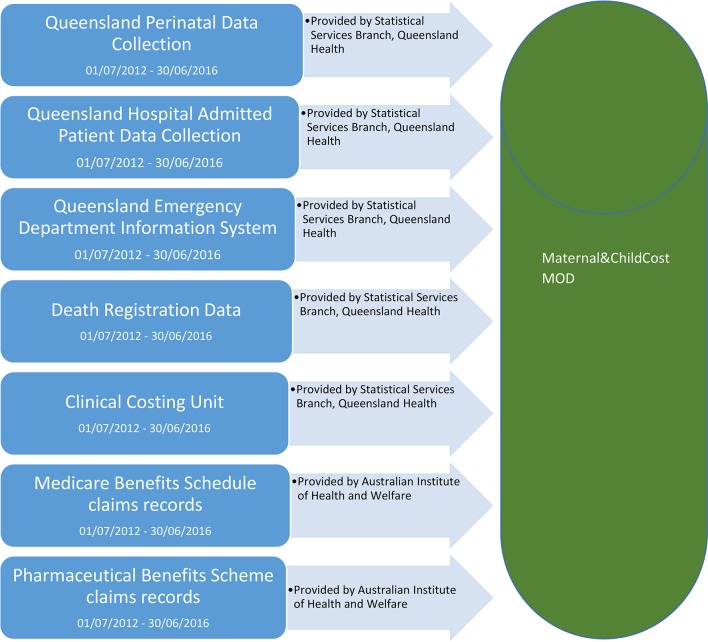

The SSB will link the patient records for all members of the cohort to their QHAPDC, Death Registration Data, EDIS and Clinical Costing Information records between 1 July 2012 and 30 June 2016 as shown in figure 2. The SSB will then remove all identifying characteristics and return the datasets to the research group at James Cook University.

Figure 2.

Datasets that will be used to create the final model.

The SSB will provide the AIHW with the identifying variables and project identifiers shown in figure 1. The AIHW will then link MBS and PBS claim records from 1 July 2012 to 30 June 2016 for individuals within the cohort. AIHW will then remove all identifying characteristics and provide access to the MBS and PBS datasets to the research group at James Cook University.

Data modification

The researchers will then assign costs associated with hospital inpatient use based on the AR-DRG code associated with each admission from the Queensland Admitted Patient Data Collection. For admissions in public hospitals, the costs will be assigned based on the average total cost for each AR-DRG classification from the National Hospital Cost Data Collection27 produced by the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority, and adjusted for paediatrics, patient remoteness, indigenous identification, dialysis, intensive care, private patient admissions and primate patient accommodation admissions, in accordance with the adjustments specified in the National Efficiency Price Determination.28 For admissions in private hospitals, the costs will be assigned based on the total cost for each AR-DRG classification from the Private Hospital Data Bureau Annual Reports,29 plus from MBS claims records, for items with a private hospital flag to indicate services used in a private hospital.

Costs for emergency department use will be assigned based on whether the patient was admitted, died, transferred or left without receiving treatment, and the triage category assigned to each presentation on the Emergency Department Information System dataset. The costs will be obtained from the National Hospital Cost Data Collection27 produced by the Independent Hospital Pricing Authority.

Travel costs will be estimated based on postcode of residence and postcode of service use, and the Australian Tax Office cents per kilometre formula will be applied to estimate car expenses.30

From this point, health system use and costs related to primary care, secondary care, prescription medication use, hospital admission and emergency department use will be captured by Maternal & Child Cost MOD, with data sources for use and cost detailed below in table 1.

Table 1.

Data sources for health service use and cost

| Resource item | Data source for number of services | Data source for cost per service use |

| PBS prescriptions | Medicare claim records | Medicare claim records |

| MBS items | Medicare claim records | Medicare claim records |

| Hospital services | Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection Emergency Department Information System |

AR-DRG codes Medicare claim records IHPA National Hospital Cost Data Collection |

| Travel—car expenses | Queensland Hospital Admitted Patient Data Collection Emergency Department Information System, Medicare claim records |

Australian Tax Office formula |

AR-DRG, Australian Refined Diagnostic Related Group; IHPA, Independant Hospital Pricing Authority; MBS, Medicare Benefits Schedule; PBS, Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme.

Price adjustment

All prices will be presented in 2016 Australian dollars, with prices adjusted by the health price index produced by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.31

Data access

The MBS and PBS dataset will be deposited into the Sure Unified Research Environment (SURE), a secure computing environment accessible remotely through an encrypted internet message. The research team will then upload all datasets provided by the Statistical Services Branch, Queensland Health. All analyses will be conducted through SURE.

Analysis

The current costs to the health system and out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure of patients attributable to maternity and early childhood healthcare will be able to be assessed, and differences between socioeconomic and geographic groups will be identified. We will use linear regression modelling and counterfactual modelling techniques to assess differences in costs, with a particular focus on:

indigenous and non-indigenous patients;

socioeconomic status (identified by those with a low-income healthcare card, or those living in the lowest two income quintiles as classified by the area-based measure of socioeconomic inequality, SEIFA, which will be identified based on postcode of residence)32;

people living in different geographic areas across Australia.

Costs to the health system and out-of-pocket costs to the patient will be analysed as continuous variables using generalised linear regression models. In addition to the socioeconomic variables listed above, confounding clinical variables will also be included when appropriate. This analysis will be conducted using SAS V.9.4.

The geographic analysis will be conducted using SAS V.9.4 and ArcGIS by Primary Health Network and Health Service District, allowing health professionals working within different areas to compare how much their patients are paying out of pocket relative to those in other areas.

The total out-of-pocket expenditure per patient will be estimated from the linked dataset per time period, defined as 10 months prior to birth to birth for the mother; birth to 12 months postpartum for the mother and for the child; 12 months to 24 months postpartum for the child; 24 to 36 months postpartum for the child; 36 to 48 months postpartum for the child; and 48 to 60 months postpartum for the child. This project will then separately look at out-of-pocket expenditure in each time frame associated with hospital admissions, out-of-hospital services and prescription pharmaceuticals. This component of the study will take a patient perspective and identify the direct costs to the patient.

The average out-of-pocket costs to the patient, per patient, will then be quantified by subpopulation group to identify any inequalities using t tests. The total out-of-pocket cost of care for each patient will be divided into quintiles and then further divided to identify the two highest expenditure groups. The analyses will be performed separately for each time period outlined above.

Logistic regression will be used to determine the odds of being a ‘high out-of-pocket cost’ patient (highest two expenditure quintiles) in relation to various explanatory variables. The explanatory variables will be income group, indigenous status, geographical location, age and sex.

The analysis will then be repeated taking a health system perspective, and identify the direct costs to the health system.

The counterfactual analysis will be undertaken using the regression models described above to assess the health system costs that would have been incurred had indigenous and non-indigenous patients, patients of low socioeconomic status and high socioeconomic status and patients in rural areas and non-rural areas had the same level of health service access. For example, for the indigenous versus non-indigenous comparison a linear regression model predicting total health system cost will be constructed, with indigenous status (dummy coded ‘0’ for non-indigenous and ‘1’ for indigenous), demographic and clinical characteristics as explanatory variables. A new variable will then be created for indigenous patients to estimate the counterfactual health system costs using the equation produced by the regression model, with the indigenous status variable set to ‘0’ rather than ‘1’.

Strengths

A common issue for studies assessing health service use is that sampling is based on those who attend health services, thereby excluding those who never made it to a service. This model used the Perinatal Data Collection to form the base population, and as such covers all births within Queensland—and is not restricted to those babies or mothers, who used a particular service.

Limitations

While the use of administrative data provides many benefits for analysis, it is acknowledged that most indirect costs will not be captured. Non-admitted patient data were not collected; therefore, private allied health visits not covered by Medicare may not be captured. Out-of-hospital services not covered by MBS will also not be captured.

Ethics and dissemination

Consent will not be sought from participants whose de-identified data will be utilised in this study. Permission to waive consent has been gained from Queensland Health under the Public Health Act 2005. No identifiable information will be provided to the authors. The results of this study will be disseminated through publications in peer-reviewed journals aimed at Australian and international medical journals. We will work with the media office at James Cook University to compile a media strategy for each publication. Our target audience is clinicians, health professionals, and health policy-makers.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EC conceived the original study design. EC and HF will undertake the statistical analysis. All authors have read and approved the final study design.

Funding: This work was supported by an Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine (AITHM) grand, and the NHMRC Centre for Research Excellence in Stillbirth (GNT1116640).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Queensland Health.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.The Department of Health. National maternity services plan. Canberra, ACT: The Department of Health, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Australian Bureau of Statistics. 3238.0.55.001 - Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. 3238.0.55.001 - Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, June 2011. 2011 Canberra, ACT: Australian Government; http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/3238.0.55.001 (accessed 25 Aug 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kildea S, Pollock WE, Barclay L. Making pregnancy safer in Australia: the importance of maternal death review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2008;48:130–6. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2008.00846.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rural PA. Rural, regional and remote health: indicators of health status and determinants of health. Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maxwell S, Brameld K, Bower C, et al. Socio-demographic disparities in the uptake of prenatal screening and diagnosis in Western Australia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2011;51:9–16. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2010.01250.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coory MD, Roselli T, Carroll HJ. Antenatal care implications of population-based trends in Down syndrome birth rates by rurality and antenatal care provider, Queensland, 1990-2004. Med J Aust 2007;186:230–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittiga C, Ettridge K, Martin K, et al. Sociodemographic correlates of smoking in pregnancy and antenatal-care attendance in Indigenous and non-Indigenous women in South Australia. Aust J Prim Health 2016;22:452–60. 10.1071/PY15081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). 2011. The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people - an overview 2011. Canberra, ACT: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; Cat no IHW 42. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Department of Health and Aging. Improving maternity services in Australia: the report of the Maternity Services Review. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alliance NRH. Submission from the national rural health alliance. Australia: National Rural Health Alliance, 2017. http://ruralhealth.org.au/ (accessed 12 Sep 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Australia’s mothers and babies 1991, Australia’s mothers and babies, Australia’s mothers and babies 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rolfe MI, Donoghue DA, Longman JM, et al. The distribution of maternity services across rural and remote Australia: does it reflect population need? BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:163 10.1186/s12913-017-2084-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hilder L, Zhichao Z, Parker M, et al. Australia’s mothers and babies 2012. 2014.

- 14.Ng SK, Cameron CM, Hills AP, et al. Socioeconomic disparities in prepregnancy BMI and impact on maternal and neonatal outcomes and postpartum weight retention: the EFHL longitudinal birth cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014;14:14 10.1186/1471-2393-14-314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abouzeid M, Versace VL, Janus ED, et al. Socio-cultural disparities in GDM burden differ by maternal age at first delivery. PLoS One 2015;10:e0117085 10.1371/journal.pone.0117085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katterl R. Socioeconomic status and accessibility to health care services in Australia. Australia: Primary Health Care Research & Information Service, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yelland JS, Sutherland GA, Brown SJ. Women’s experience of discrimination in Australian perinatal care: the double disadvantage of social adversity and unequal care. Birth 2012;39:211–20. 10.1111/j.1523-536X.2012.00550.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callander EJ, Corscadden L, Levesque JF. Out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure and chronic disease ? do Australians forgo care because of the cost? Aust J Prim Health. 2016 doi: 10.1071/PY16005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Australian Government. Health Dof, Medicare Benefits Schedule Book: Operating from 01 September 2017. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett CC. A healthier future for all Australians: an overview of the final report of the National Health and Hospitals Reform Commission. Med J Aust 2009;191:383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Patient Experiences in Australia: summary of findings, 2015-16. Canberra, Australia: Australian Burea of Statistics, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Australian Government. Extended medicare safety net. Canberra, Australia: Department of Human Services, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Statistics AB, Births, Australia, 2015. Canberra, Australia: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Australian Bureau of Statistics. Population distribution in Australian social trends. Caberra: ABS, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oliver L, Wood M, Frawley C, et al. Retrospective audit of postnatal attendance for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women attending a community-controlled health service in north Queensland. Aust Fam Physician 2015;44:243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Australian Bureau of Statistics. National efficient price determination. Canberra: ABS, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Independent Hospital Pricing Authority. National hospital cost data collection, AR-DRG cost weight tables V6.0x, round 17 (Financial year 2012-13. New South Wales, Australia: IHPA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Independent Hospital Pricing Authority. National efficient price determination. New South Wales, Australia: IHPA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Department of Health. Private Hospital Data Bureau (PHDB) Annual Reports. Canberra, Australia: The Department of Health, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Australian Taxation Office. Cents per kilometre method. Canberra, Australia: Australian Taxation Office, 2017. https://www.ato.gov.au/Business/Income-and-deductions-for-business/Deductions/Motor-vehicle-expenses/Claiming-motor-vehicle-expenses-as-a-sole-trader/Cents-per-kilometre-method/ (accessed 15 Sep 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health expenditure Australia 2014 to 2015. Canberra: AIHW, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2011. Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas (SEIFA) Technical paper ABS. Canberra: ABS; Cat. No. 2033.0.55.001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.