Abstract

Objective

To examine recent time trends in the incidence of osteonecrosis (ON) in Denmark and to investigate different common comorbidities association with ON in a population-based setting.

Methods

Using Danish medical databases, we included all patients with a first-time hospital diagnosis of ON during 1995–2012. Each ON case was matched with 10 randomly selected population control subjects from general population. For all participants, we obtained a complete hospital history of comorbidities included in the CharlsonComorbidity Index 5 years preceding the inclusion date.

Results

4107 ON cases and 41 063 controls were included. The incidence of ON increased from 3.9 in 1995 to 5.5 in 2012 per 100 000 inhabitants. Solid cancer was the most common comorbidity, associated with an adjusted OR (aOR) for ON of 2.0 (95% CI 1.7 to 2.2). For advanced metastatic cancer, leukaemia and lymphoma, aORs of ON were 3.4 (95% CI 2.5 to 4.5), 4.3 (95% CI 2.7 to 7.0) and 5.8 (95% CI 4.3 to 7.8), respectively. Among other chronic conditions, aORs were 3.5 (95% CI 3.0 to 4.1) for connective tissue diseases and 2.3 (95% CI 2.0 to 2.7) for chronic pulmonary diseases. aORs were also increased at 2.8 (95% CI 1.9 to 4.1) and 4.5 (95% CI 2.5 to 8.2) for mild and moderate-to-severe liver disease, respectively, and 4.2 (95% CI 3.4 to 5.2) for renal disease.

Conclusion

This large population-based study provides evidence for an increasing ON incidence in the general population and documents an association between several common comorbid conditions and risk of ON.

Keywords: osteonecrosis, Denmark, comorbidity, incidence, Charlson index

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large nationwide study within the setting of a universal healthcare system that grants complete and uniform health data collection.

Population-based case–control design with 10 population control subjects for each osteonecrosis (ON) case, matched by sex, age, ethnicity and geographical region and diminishing the risk of selection bias.

The International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision codes did not allow for evaluating the type and location of ON.

We lacked information on some confounders potentially associated with both comorbidity and ON risk, including lifestyle factors and certain medications.

Introduction

The exact incidence of osteonecrosis (ON), a rare disorder with severe clinical outcomes, remains unknown in most countries and reported risk estimates vary substantially.1–4 In Great Britain, annual ON incidences ranged from 1.4 to 3.0 per 100 000 inhabitants between 1989 and 2003,2 while incidence rates lower than 1.0 per 100 000 inhabitants were reported in the Netherlands in 2003–2004.3 For femoral ON, reportedly comprising around 80% of all ON events,2 5 up to 6.3 episodes per 100 000 inhabitants have been predicted to occur in the USA4; while other authors suggested more than 15 ON cases per 100 000 inhabitants when evaluating total joint arthroplasties.1 From Asia, a non-traumatic femoral ON incidence of 2.5 cases per 100 000 inhabitants has been reported in the Fukuoka Prefecture of Japan.6

Among patients with cancer,7 8 pulmonary diseases,5 9–11 immunological conditions,8 11 12 renal diseases13 or organ transplantation,8 14 15 corticosteroid therapy has been associated with increased risk of ON. Further, important lifestyle factors, including tobacco use16 17 and high alcohol consumption,16–18 may increase ON risk.

A few specific comorbid medical conditions have been associated with increased risk of ON.4 19–21 The clinical implications of these findings may be limited, since many of the reported diseases, like sickle cell haemoglobinopathy, Gaucher disease, systemic lupus erythematosus or caisson disease are relatively rare.19 21

In contrast, data are scarce about the impact of frequently occurring diseases in middle-aged and elderly populations on the risk of ON which may be of greater clinical and public health importance. In order to fill the gap in our current knowledge, we investigated recent time trends in the incidence of ON in Denmark and examined the association between a number of common comorbidities included in the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) and the risk of incident ON.

Methods

Setting

A population-based case–control study was conducted in the entire Danish population (approximately 5.6 million inhabitants).22 The Danish National Health Service provides universal, tax-supported healthcare. The Danish National Registry of Patients (DNRP) holds information on all non-psychiatric hospital admissions since 1977 and hospital clinic outpatient visits since 1995. Each hospital contact is accompanied by up to 20 discharge diagnoses coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) since 1994. Accurate linkage of all databases is possible by means of a unique 10-digit personal number assigned to each Danish citizen and included in all medical and public registries.

Study population

The study population consisted of all patients (cases) with a first ON diagnosis identified in the DNRP from 1995 through 2012. We used the following ICD-10 codes: idiopathic aseptic necrosis of the bone (M87.0), ON due to drugs (M87.1), ON due to previous trauma (M87.2), other secondary ON (M87.3), other ON (M87.8) and unspecified ON (M87.9).

Selection of population controls

The Danish Civil Registry System was used to randomly select 10 population control subjects for each case on the date of first ON diagnosis (index date for controls). All control subjects were matched by age, sex, ethnicity (native vs immigrants) and residency (same county). To be eligible for this study, subjects in the control group were not allowed to have a hospitalisation with an ON diagnosis before the admission date for the corresponding ON case.

Comorbidities

In the present study, comorbidities were defined according to the CCI (see online supplementary appendix). Using ICD-10 codes as previously reported,23 data on all comorbidities up to a 5-year period prior to the index date in cases and controls were obtained from the DNRP. The predictive positive value of these CCI comorbidities is documented high in the DNRP.23 We also defined several severity levels of comorbidity, categorised as none (CCI score 0, thus having no recorded hospital-diagnosed comorbidities), mild comorbidity (CCI score 1 or 2), moderate comorbidity (CCI score 3 or 4) and severe comorbidity (CCI score 5+).

bmjopen-2017-020680supp001.pdf (256.2KB, pdf)

Statistical analysis

We estimated annual incidence rates of ON per 100 000 inhabitants as the number of new diagnosed ON cases occurring in the entire Denmark per year divided by the number of residents 1 January in the year of interest. Denominator data were available from Statistics Denmark.24 We tabulated baseline characteristics of cases with first ON diagnosis and matched population control subjects. We then computed ORs and 95% CIs for each comorbidity to proximate the relative risk of ON occurrence. Adjusted ORs (aORs) were computed using multivariable logistic regression models, mutually adjusting for all other comorbidities than the one of interest. Due to the matched case–control design, all ORs were adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity and place of residence, too. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software (V.9.2).

Results

Incidence rates of ON

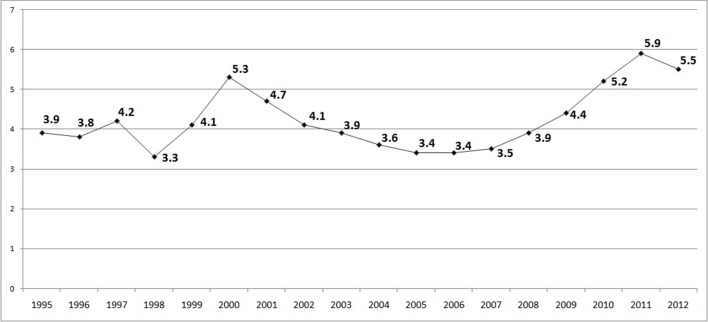

The overall mean annual incidence of ON in Denmark was 4.2 per 100 000 inhabitants for the period 1995–2012 (ranging between 3.3 and 5.9 per 100 000 inhabitants).

As presented in figure 1, a fluctuating ON incidence was observed especially for the first half of the study period, between 1995 and 2004. An upward trend was noted from 2005 onwards, with a mean annual incidence reaching 5.5 per 100 000 inhabitants during the last 3 years, 2010–2012.

Figure 1.

Osteonecrosis annual incidence rates per 100 000 inhabitants, Denmark, 1995–2012.

Characteristics of patients with ON

We identified 4107 patients with a first time ON-related hospitalisation (table 1). The proportion of patients with no hospital-diagnosed comorbidity recorded was much greater among controls than in ON cases (81.1% vs 59.0%). The proportions with mild, moderate and severe comorbidity levels among cases versus controls were 29.4% versus 15.6%, 7.2% versus 2.4% and 4.3% versus 0.8%, respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of cases with first-incident osteonecrosis and matched population control subjects, Denmark, 1995–2011

| Characteristic | Osteonecrosis cases | Population controls |

| Overall, n | 4107 | 41 063 |

| Females, n (%) | 2202 (53.6) | 22 014 (53.6) |

| Age groups | ||

| <65 years, n (%) | 2336 (56.9) | 23 362 (56.9) |

| +65 years, n (%) | 1771 (43.1) | 17 701 (43.1) |

| Comorbidity level | ||

| None (CCI score 0), n (%) | 2425 (59.0) | 33 298 (81.1) |

| Mild (CCI score 1–2), n (%) | 1209 (29.4) | 6420 (15.6) |

| Moderate (CCI score 3–4), n (%) | 296 (7.2) | 998 (2.4) |

| Severe (CCI score 5+), n (%) | 177 (4.3) | 347 (0.8) |

| Calendar year period | ||

| 1995–1997, n (%) | 627 (15.3) | 6270 (15.3) |

| 1998–2000, n (%) | 675 (16.4) | 6750 (16.4) |

| 2001–2003, n (%) | 679 (16.5) | 6790 (16.5) |

| 2004–2006, n (%) | 559 (13.6) | 5584 (13.6) |

| 2007–2009, n (%) | 648 (15.8) | 6479 (15.8) |

| 2010–2012, n (%) | 919 (22.4) | 9190 (22.4) |

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Solid cancer was the most common pre-existing condition, present in 408 ON cases (9.9%) and 1806 controls (4.4%). Compared with controls, ON cases were also much more likely to have previous diagnosis of most other conditions, including chronic pulmonary disease, connective tissue diseases or diabetes (8.5% vs 3.3%, 6.1 vs 1.6% and 5.9% vs 2.7%, respectively). The prevalence of all CCI diseases is listed in table 2.

Table 2.

OR for the association of chronic conditions with incident osteonecrosis

| Osteonecrosis cases | Population controls | Unadjusted matched OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR (95% CI)* | |

| n=4107 | n=41 063 | |||

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 76 (1.9) | 680 (1.7) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.4) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.1) |

| Congestive heart failure, n (%) | 170 (4.1) | 844 (2.1) | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.4) | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 153 (3.7) | 747 (1.8) | 2.1 (1.8 to 2.5) | 1.6 (1.3 to 1.9) |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 226 (5.5) | 1556 (3.8) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.4) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 56 (1.4) | 385 (0.9) | 1.5 (1.1 to 1.9) | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.8) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease, n (%) | 349 (8.5) | 1346 (3.3) | 2.7 (2.4 to 3.1) | 2.3 (2.0 to 2.7) |

| Connective tissue disease, n (%) | 251 (6.1) | 666 (1.6) | 4.0 (3.4 to 4.6) | 3.5 (3.0 to 4.1) |

| Ulcer disease, n (%) | 147 (3.6) | 547 (1.3) | 2.8 (2.3 to 3.3) | 2.0 (1.6 to 2.4) |

| Mild liver disease, n (%) | 47 (1.1) | 101 (0.2) | 4.7 (3.3 to 6.7) | 2.8 (1.9 to 4.1) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 242 (5.9) | 1117 (2.7) | 2.2 (2.0 to 2.6) | 1.6 (1.4 to 2.0) |

| Hemiplegia, n (%) | 18 (0.4) | 47 (0.1) | 3.8 (2.2 to 6.6) | 2.5 (1.3 to 4.6) |

| Moderate to severe renal disease, n (%) | 159 (3.9) | 281 (0.7) | 5.9 (4.8 to 7.1) | 4.2 (3.4 to 5.2) |

| Diabetes with end organ damage, n (%) | 120 (2.9) | 549 (1.3) | 2.2 (1.8 to 2.7) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.5) |

| Any tumour, n (%) | 408 (9.9) | 1806 (4.4) | 2.4 (2.1 to 2.7) | 2.0 (1.7 to 2.2) |

| Leukaemia, n (%) | 34 (0.8) | 55 (0.1) | 6.2 (4.1 to 9.6) | 4.3 (2.7 to 7.0) |

| Lymphoma, n (%) | 87 (2.1) | 121 (0.3) | 7.3 (5.6 to 9.7) | 5.8 (4.3 to 7.8) |

| Moderate to severe liver disease, n (%) | 27 (0.7) | 28 (0.1) | 9.7 (5.7 to 16.5) | 4.5 (2.5 to 8.2) |

| Metastatic solid tumour, n (%) | 102 (2.5) | 174 (0.4) | 6.0 (4.7 to 7.7) | 3.4 (2.5 to 4.5) |

| HIV/AIDS, n (%) | 10 (0.2) | 20 (0.0) | 5.0 (2.3 to 10.7) | 4.1 (1.8 to 9.2) |

*Mutually adjusted comorbidities.

aOR, adjusted OR.

Association of comorbidities with ON

Table 2 shows associations between each CCI disease category and the risk of ON. In matched unadjusted analyses, the moderate-to-severe liver disease (9.7, 95% CI 5.7 to 16.5), lymphoma (OR 7.3, 95% CI 5.6 to 9.7) and leukaemia (OR 6.2, 95% CI 4.1 to 9.6) categories were associated with the highest relative risk of incident ON. After mutually controlling for other than exposure comorbidities, the strength of these and most other associations decreased. Solid cancer, the most common comorbidity in ON, was associated with an aOR of 2.0 (95% CI 1.7 to 2.2). For advanced metastatic cancers, leukaemia and lymphoma, aORs of ON were 3.4 (95% CI 2.5 to 4.5), 4.3 (95% CI 2.7 to 7.0) and 5.8 (95% CI 4.3 to 7.8), respectively. In addition, aORs were 2.8 (95% CI 1.9 to 4.1) and 4.5 (95% CI 2.5 to 8.2) for mild and moderate-to-severe liver disease, respectively, and also substantially increased at 4.2 (95% CI 3.4 to 5.2) for renal disease. Adjusted ON risk estimates were lowest for cardiovascular diseases such as myocardial infarction (aOR 0.8, 95% CI 0.7 to 1.1), congestive heart failure (aOR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.6), peripheral vascular disease (aOR 1.6, 95% CI 1.3 to 1.9) and cerebrovascular disease (aOR 1.2, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.4), while the aOR for diabetes was 1.6 (95% CI 1.4 to 2.0).

Discussion

This large population-based study showed that the incidence of ON in Denmark was 4.2 per 100 000 during 1995–2012. ON incidence increased by 40% over 18 years, corroborating increasing time trends observed in other studies.2 25

Four out of ten patients with ON were burdened with major comorbid conditions before ON diagnosis, with malignancies, liver disease and renal disease showing the strongest association with ON.

The highest ON incidence was seen in 2011, at 5.9 per 100 000 inhabitants. The rising ON incidence over time may be related to an increasing use of corticosteroid therapy in the Danish population, although available data on overall corticosteroid use are scarce,26 or may be related to the general longevity and increase in comorbidity burden observed in the general population.27 Alternatively, the observed trends may reflect the use of more sensitive diagnostic tools, especially MRI.2

Several factors, like radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy may be involved in a causal relationship of malignancies with incident ON.7 Bisphosphonates used, for example, in the management of multiple myeloma28 and bone metastases29 have been related to ON of the jaw.30 For haematological cancers, hyperviscosity-induced leukostasis and leukaemic infiltration have been suspected as underlying mechanisms.31 Moreover, bone marrow transplantation is reportedly accompanied by a cumulative ON incidence after 10 years of 2.9%–15.5%.32 Younger age at transplantation, graft-versus-host disease14 and corticosteroid use14 15 might promote ON occurrence in transplant receivers.

Immunological conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus,11 12 Sjogren’s syndrome,8 11 dermatomyositis,8 mixed connective tissue disease,8 rheumatoid arthritis,8 adult-onset Still disease11 or scleroderma11 have previously been associated with increased risk of ON. These associations may be mediated by use of corticosteroids8 or other immunosuppressive drugs,33 or may be related to the specific disease activity itself.34

There are few data in the literature regarding a positive association between chronic pulmonary disease and increased risk of ON, as documented in our study. Presence of asthma has been reported in 4.5% of patients with steroid-induced femoral ON8 and 8.0% of those with humeral ON.5 Cooper et al2, in a case–control study, found a crude OR of 1.7 for an association of asthma with ON. Another study found no dose–response relationship between chronic corticosteroid use and risk of hip ON development.9 On the contrary, in severe acute respiratory syndrome, risk of ON appeared to be correlated with the maximal corticosteroid daily dose used.10 Tobacco smoking is a strong risk factor for many chronic pulmonary diseases, and current smoking itself has been associated with a relative risk for ON of 3.9–4.7.16 17

Hepatic diseases have previously been associated with a 5.0-fold increase for incident ON16 35 in accordance with our findings. Alcohol overuse is a known ON risk factor.16–18 35 Previous studies found an estimated relative risk for ON development of 3.2 for occasional alcohol drinking,17 7.8–13.1 for regular drinkers16 17 and 17.9 in current drinkers with intake of greater than 1000 mL of alcohol weekly.16 However, other factors than alcohol intake may play a role for increased ON risk in liver diseases.35 ON occurrence seems to be lower in patients who have an immediate increase of cytolysis liver enzymes under steroid therapy, than in those without this quick response.36 Furthermore, alcohol-related ON seems to be more closely associated with alcoholic liver disease than with alcohol-related pancreatic disease.37 Also, other pathologies associated with bone impairment, including thrombocytopenia,8 anaemia19 or malnutrition with calcium and vitamin D deficiencies38 are frequently found in patients with cirrhosis.

The association between diabetes and ON occurrence has been debated. Thus, some19 21 but not all4 20 studies have reported diabetes as a risk factor for ON. Our study adds to the evidence, showing that diabetes is associated with a 1.6-fold increased risk of ON.

Only few studies have investigated the association between renal disorders and ON. A nationwide study found nephrotic syndrome to be present in 6.3%, nephritis in 2.5% and previous renal transplantation in 3.6% of patients with ON treated with corticosteroids.8 ON occurrence in patients with renal pathology was at least partially attributed to corticosteroid use in other studies13 20 but also to the underlying disease.34 In patients with renal transplantation, any ON lesions tend to occur rapidly after surgery; renal homeostasis alteration as expressed by urea nitrogen levels39 or metabolic changes, like high calcium and low phosphorus levels, seems to increase the risk of ON development.40

Finally, our findings of an association between HIV infection and ON confirm results found in previous studies.41 42

Our study has some limitations. The hospital diagnosis codes do not capture in detail the severity of the chronic diseases nor their medical therapy. Still, this limitation is present both in cases and controls with sparse effect on our relative risk estimates. Also, ICD-10 codes do not properly capture the type and location of ON. In a recent report, of 83 jaw ON cases confirmed in medical records during a period of 5 years, only two cases were coded using M87.1 and 8 cases were coded using M87.8, while other ICD-10 codes than those used in our report were used for the rest of the cases (K04.6, K10.2 or K10.3).30 Thus, our comorbidity results likely cannot be generalised to jaw ON, which has rather different risk factors and prognosis than other ON cases. Also, we lacked information on potential important confounders such as lifestyle factors including smoking and alcohol consumption, and prescription medication including corticosteroids and immunosuppressive drugs, which may lead to residual confounding and an overestimation of the risk conferred by comorbidities. Nonetheless, we were able to mutually adjust for several comorbid conditions as surrogate measures, for example, chronic pulmonary diseases, lung cancer or peripheral vascular disease as markers of smoking, and connective tissue diseases, pulmonary diseases or haematological cancers as markers of corticosteroid use.

Our study also has several strengths, including its large size and a case–control design within the setting of a universally covering healthcare system that grants complete and uniform data collecting throughout the entire Denmark. In order to control for confounding, we could match ON cases and controls by sex, age, ethnicity and geographical region. Control subjects were randomly selected from the Central Population Registry among the study base giving rise to ON cases, diminishing risk of selection bias. There is no recall bias in our case–control study because the data on comorbidity are based on information already prospectively collected, independently of our study goals. The comorbidities analysed were coded prior the index date and are thus unlikely to be ON sequels.

In conclusion, this large population-based study provided evidence that the incidence of ON has increased over the last decade in Denmark. Common chronic conditions including cancer, chronic pulmonary disease, liver and renal disease and diabetes are all associated with substantially increased risk of ON, and increases in the prevalence of these diseases in the population may also underlie the increasing ON trend observed.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: ABP defined the study idea. AD, ABP, LP, CB and RWT conceived the paper. AD, CB and RWT wrote the study protocol. LP extracted the data and led the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to data interpretation. AD wrote the first draft with further contribution from RWT and ABP. All authors critically reviewed successive drafts and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional unpublished data from this study.

References

- 1.Mankin HJ. Nontraumatic necrosis of bone (osteonecrosis). N Engl J Med 1992;326:1473–9. 10.1056/NEJM199205283262206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper C, Steinbuch M, Stevenson R, et al. The epidemiology of osteonecrosis: findings from the GPRD and THIN databases in the UK. Osteoporos Int 2010;21:569–77. 10.1007/s00198-009-1003-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gosling-Gardeniers AC, Rijnen WHC, Gardeniers JWM. The Prevalence of Osteonecrosis in Different Parts of the World Osteonecrosis. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014:35–7. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lavernia CJ, Sierra RJ, Grieco FR. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1999;7:250–61. 10.5435/00124635-199907000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mont MA, Payman RK, Laporte DM, et al. Atraumatic osteonecrosis of the humeral head. J Rheumatol 2000;27:1766–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamaguchi R, Yamamoto T, Motomura G, et al. Incidence of nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head in the Japanese population. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:3169–73. 10.1002/art.30484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shim K, MacKenzie MJ, Winquist E. Chemotherapy-associated osteonecrosis in cancer patients with solid tumours: a systematic review. Drug Saf 2008;31:359–71. 10.2165/00002018-200831050-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fukushima W, Fujioka M, Kubo T, et al. Nationwide epidemiologic survey of idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:2715–24. 10.1007/s11999-010-1292-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colwell CW, Robinson CA, Stevenson DD, et al. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head in patients with inflammatory arthritis or asthma receiving corticosteroid therapy. Orthopedics 1996;19:941–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Griffith JF, Antonio GE, Kumta SM, et al. Osteonecrosis of hip and knee in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome treated with steroids. Radiology 2005;235:168–75. 10.1148/radiol.2351040100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shigemura T, Nakamura J, Kishida S, et al. Incidence of osteonecrosis associated with corticosteroid therapy among different underlying diseases: prospective MRI study. Rheumatology 2011;50:2023–8. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dima A, Pedersen AB, Pedersen L, et al. Risk of osteonecrosis in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: A nationwide population-based study. Eur J Intern Med 2016;35:e23–e24. 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka Y. Corticosteroid therapy for nephrotic syndrome. Nihon Rinsho 2004;62:1867–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Torii Y, Hasegawa Y, Kubo T, et al. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;382:124–32. 10.1097/00003086-200101000-00019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fink JC, Leisenring WM, Sullivan KM, et al. Avascular necrosis following bone marrow transplantation: a case-control study. Bone 1998;22:67–71. 10.1016/S8756-3282(97)00219-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuo K, Hirohata T, Sugioka Y, et al. Influence of alcohol intake, cigarette smoking, and occupational status on idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988;234:115–23. 10.1097/00003086-198809000-00021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hirota Y, Hirohata T, Fukuda K, et al. Association of alcohol intake, cigarette smoking, and occupational status with the risk of idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head. Am J Epidemiol 1993;137:530–8. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fukushima W, Yamamoto T, Takahashi S, et al. The effect of alcohol intake and the use of oral corticosteroids on the risk of idiopathic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: a case-control study in Japan. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:320–5. 10.1302/0301-620X.95B3.30856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Assouline-Dayan Y, Chang C, Greenspan A, et al. Pathogenesis and natural history of osteonecrosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002;32:94–124. 10.1053/sarh.2002.33724b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mont MA, Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head: ten years later. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:1117–32. 10.2106/JBJS.E.01041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malizos KN, Karantanas AH, Varitimidis SE, et al. Osteonecrosis of the femoral head: etiology, imaging and treatment. Eur J Radiol 2007;63:16–28. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish Civil Registration System as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol 2014;29:541–9. 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, et al. The predictive value of ICD-10 diagnostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity index conditions in the population-based Danish National Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:83 10.1186/1471-2288-11-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Statistics Denmark. HISB3: summary vital statistics. 2015. http://www.statbank.dk/HISB3.

- 25.Takahashi S, Fukushima W, Yamamoto T, et al. Temporal Trends in Characteristics of Newly Diagnosed Nontraumatic Osteonecrosis of the Femoral Head From 1997 to 2011: A Hospital-Based Sentinel Monitoring System in Japan. J Epidemiol 2015;25:437–44. 10.2188/jea.JE20140162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davidsen JR, Søndergaard J, Hallas J, et al. Increased use of inhaled corticosteroids among young Danish adult asthmatics: an observational study. Respir Med 2010;104:1817–24. 10.1016/j.rmed.2010.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ording AG, Sørensen HT. Concepts of comorbidities, multiple morbidities, complications, and their clinical epidemiologic analogs. Clin Epidemiol 2013;5:199–203. 10.2147/CLEP.S45305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Badros A, Weikel D, Salama A, et al. Osteonecrosis of the jaw in multiple myeloma patients: clinical features and risk factors. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:945–52. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varun B, Sivakumar T, Nair BJ, et al. Bisphosphonate induced osteonecrosis of jaw in breast cancer patients: A systematic review. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2012;16:210–4. 10.4103/0973-029X.98893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ehrenstein V, Gammelager H, Schiødt M, et al. Evaluation of an ICD-10 algorithm to detect osteonecrosis of the jaw among cancer patients in the Danish National Registry of Patients. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2015;24:693–700. 10.1002/pds.3786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moon JY, Kim BS, Yun HR, et al. A case of avascular necrosis of the femoral head as initial presentation of chronic myelogenous leukemia. Korean J Intern Med 2005;20:255–9. 10.3904/kjim.2005.20.3.255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell S, Sun CL, Kurian S, et al. Predictors of avascular necrosis of bone in long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cancer 2009;115:4127–35. 10.1002/cncr.24474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee J, Kwok SK, Jung SM, et al. Osteonecrosis of the hip in Korean patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: risk factors and clinical outcome. Lupus 2014;23:39–45. 10.1177/0961203313512880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fialho SC, Bonfá E, Vitule LF, et al. Disease activity as a major risk factor for osteonecrosis in early systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus 2007;16:239–44. 10.1177/0961203307076771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shibata A, Fukuda K, Inoue A, et al. Flushing pattern and idiopathic avascular necrosis of the femoral head. J Epidemiol 1996;6:37–43. 10.2188/jea.6.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okazaki S, Nagoya S, Yamamoto M, et al. High risk of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in autoimmune disease patients showing no immediate increase in hepatic enzyme under steroid therapy. Rheumatol Int 2013;33:51–5. 10.1007/s00296-011-2295-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chao YC, Wang SJ, Chu HC, et al. Investigation of alcohol metabolizing enzyme genes in Chinese alcoholics with avascular necrosis of hip joint, pancreatitis and cirrhosis of the liver. Alcohol Alcohol 2003;38:431–6. 10.1093/alcalc/agg106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lim CY, Ong KO. Various musculoskeletal manifestations of chronic renal insufficiency. Clin Radiol 2013;68:e397–411. 10.1016/j.crad.2013.01.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Inoue S, Horii M, Asano T, et al. Risk factors for nontraumatic osteonecrosis of the femoral head after renal transplantation. J Orthop Sci 2003;8:751–6. 10.1007/s00776-003-0716-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Briggs WA, Hampers CL, Merrill JP, et al. Aseptic necrosis in the femur after renal transplantation. Ann Surg 1972;175:282–9. 10.1097/00000658-197202000-00022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller KD, Masur H, Jones EC, et al. High prevalence of osteonecrosis of the femoral head in HIV-infected adults. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:17–25. 10.7326/0003-4819-137-1-200207020-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Allison GT, Bostrom MP, Glesby MJ. Osteonecrosis in HIV disease: epidemiology, etiologies, and clinical management. AIDS 2003;17:1–9. 10.1097/01.aids.0000042940.55529.93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-020680supp001.pdf (256.2KB, pdf)