Abstract

Background

Hearing loss impacts on cognitive, social and physical functioning. Both hearing loss and hearing aid use vary across population subgroups. We examined whether hearing loss, and reported current hearing aid use among persons with hearing loss, were associated with different markers of socioeconomic status (SES) in a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults.

Methods

Hearing was measured using an audiometric screening device in the Health Survey for England 2014 (3292 participants aged 45 years and over). Hearing loss was defined as >35 dB HL at 3.0 kHz in the better-hearing ear. Using sex-specific logistic regression modelling, we evaluated the associations between SES and hearing after adjustment for potential confounders.

Results

26% of men and 20% of women aged 45 years and over had hearing loss. Hearing loss was higher among men in the lowest SES groups. For example, the multivariable-adjusted odds of hearing loss were almost two times as high for those in the lowest versus the highest income tertile (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.74). Among those with hearing loss, 30% of men and 27% of women were currently using a hearing aid. Compared with men in the highest income tertile, the multivariable-adjusted odds of using a hearing aid nowadays were lower for men in the middle (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.99) and the lowest (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.97) income tertiles. Associations between SES and hearing were weaker or null among women.

Conclusions

While the burden of hearing loss fell highest among men in the lowest SES groups, current hearing aid use was demonstrably lower. Initiatives to detect hearing loss early and increase the uptake and the use of hearing aids may provide substantial public health benefits and reduce socioeconomic inequalities in health.

Keywords: hearing loss, hearing aids, surveys, epidemiology, social inequalities

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Estimates of the burden of hearing loss, the use of hearing aids among persons with hearing loss and their associations with socioeconomic status are rarely available from nationally representative health examination surveys.

We used data from a screening audiometry device to estimate the prevalence of hearing loss. The prevalence of current hearing aid use was estimated among persons with hearing loss.

The associations between different markers of socioeconomic status and hearing were examined after adjustment for a wide range of confounders such as age, exposure to work-related noise and risk factors for cardiovascular disease.

Exclusion of persons from the study due to difficulties in interviewer–participant communication through conditions such as deafness means that our estimates are likely to underestimate the true prevalence of hearing loss among community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults.

Introduction

Hearing loss is well known to impact on cognitive, social and physical functioning.1–3 It can be congenital, but most is acquired and is sensorineural and irreversible in nature.4 Preventing hearing loss requires understanding its aetiology and risk factors.5 Epidemiological studies have shown that hearing loss increases with age6–8 and increases with the duration of exposure to work-related noise.8 It is higher among men,6–8 higher among persons with cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors6 8–11 and is inversely associated with socioeconomic status (SES).6–8 12 Early detection and hearing aid use may be effective at ameliorating the impact of hearing loss.13 However, levels of hearing aid use among persons most likely to benefit are low,14–17 especially among persons with hearing loss in the lowest SES groups.14 18–20

Based on the UK National Study of Hearing conducted in four cities in the early 1980s, 16% of adults aged 17–80 years had a bilateral, and 25% had a unilateral or bilateral, hearing loss.21 Uptake and use of hearing aids was low, with uptake being 10%–30% among persons with hearing loss, and up to 25% of hearing aid owners never using them.22 To provide up-to-date estimates of the burden of hearing loss, the Health Survey for England (HSE) 2014 included, for the first time in a nationally representative sample of the population, valid screening audiometry data. The aim of this study was to estimate the prevalence of (1) hearing loss and (2) current hearing aid use (among persons with hearing loss), in this sample of community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults across population subgroups defined by demographics, work-related noise exposure and by the presence of CVD risk factors. We also examined the associations between SES and hearing.

Methods

Study population

The present study used data from the HSE. The HSE is an annual, nationally representative cross-sectional survey of the non-institutionalised general population of all ages. A maximum of two children per household contributed to the 2014 survey. In households with more than two children, two were randomly selected using the Kish grid method.23 Multistage stratified probability sampling is used with postcode sectors as the primary sampling unit and the Postcode Address File as the sampling frame for households. Details about the HSE are described elsewhere.23 Interview and nurse-visit response rates were 55% and 37%, respectively. Participants gave verbal consent to be interviewed, visited by a nurse, participate in a hearing test and have blood pressure and anthropometric measurements taken, and gave written consent for blood sampling.

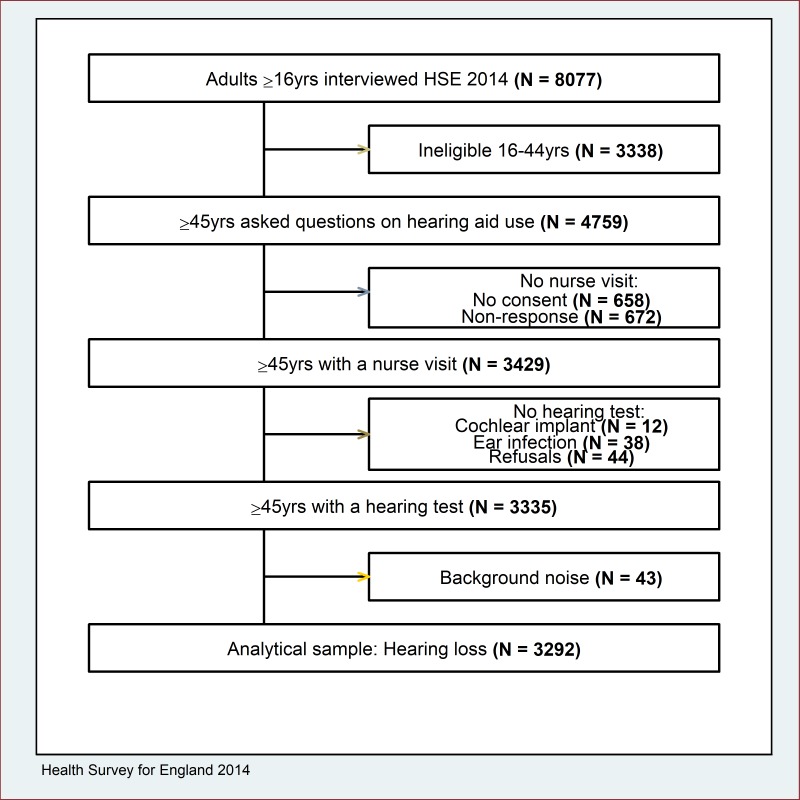

Overall, 8077 participants aged ≥16 years were interviewed, including questions on the use of hearing aids (see section on current hearing aid use). All participants aged ≥16 years who had a nurse-visit were eligible for the hearing test, excluding those with a cochlear implant or with a current ear infection (figure 1). Participants aged 16–44 years were excluded due to hearing loss being comparatively rare (n=46). In addition, a number of persons would have been excluded if interviewer–participant communication difficulties through conditions such as deafness were sufficient to prevent inclusion in the study. The final analytical sample was 3292 participants.

Figure 1.

Selection of study participants, Health Survey for England (HSE) 2014.

Hearing test

Hearing was measured using an audiometric screening device (HearCheck screener, Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) in participants' own homes. Two evaluation studies comparing the results of the screener to pure tone audiometry showed good sensitivity (range: 78%–92%) and acceptable to good specificity (62%–95%).24 25 This handheld device produced a series of three sounds of decreasing volume at 1.0 kHz (55 dB HL, 35 dB HL and 20 dB HL) and then at 3.0 kHz (75 dB HL, 55 dB HL and 35 dB HL). Both ears were tested, starting with the left. Participants were instructed to indicate when they heard a noise by raising their finger. If an irregular pattern was found (a combination of responses indicating that quieter sounds were heard but louder ones were not), the test was repeated at least 60 s later for that ear. Participants with an irregular pattern at the first test, but a regular pattern at the second test, were included in the analyses. Further details of the testing procedures are available elsewhere.17

Outcomes

Hearing loss

Hearing loss was defined as >35 dB HL at 3.0 kHz in the better-hearing ear, the level at which intervention has been shown to be definitely beneficial.26 More specifically, a comparison of different screen programmes conducted as part of the NHS Health Technology Assessment Programme showed that hearing loss of >35 dB HL at 3.0 kHz was the best predictor (in terms of the d-prime statistic: a combination of good sensitivity and low false alarm rate) for the ability of persons to gain the greatest benefit from hearing aids.26 Hearing loss of >35 dB HL at 3.0 kHz had 88% sensitivity and 10% false alarm rate.26 Hearing loss was subdivided into two mutually exclusive categories: (1) ‘moderate loss’: >35 dB HL to 54 dB HL (tone not heard at 35 dB HL, but heard at 55 dB HL and at 75 dB HL) and (2) ‘moderately severe or severe loss’: >55 dB HL (tone not heard at 35 dB HL and at 55 dB HL, but the tone may, or may not, have been heard at 75 dB HL). Prevalence estimates were multiplied by the 2014 household population to estimate the number of people with hearing loss.27

Current hearing aid use

As part of the main interview, all participants were asked if they ever wore a hearing aid nowadays: those who answered negatively were asked whether they had ever tried one. Current hearing aid use, for the purposes of the present study, consisted of those participants who answered positively to the question about use of a hearing aid nowadays. Participants classed as not currently using a hearing aid consisted of those who had tried hearing aids in the past but did not use a hearing aid nowadays, and those who had never tried a hearing aid.

Markers of socioeconomic status

Tertiles of equivalised household income, quintiles of the area-based Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD 2010: Q1 least deprived; Q5 most deprived),28 and the highest formal educational attainment (degree or higher, below degree, no qualifications) were chosen as related, but different, markers of SES. Broader categories of SES were used for the analysis of current hearing aid use among persons with hearing loss due to smaller sample sizes. The IMD 2010 quintiles were recoded into three categories: Q1 and Q2 (least deprived), Q3, and Q4 and Q5 (most deprived). Educational status was recoded into two categories: O level and above, and no qualifications.

Covariates

Covariates were grouped into: (1) demographic characteristics (age, region), (2) exposure to work-related noise and (3) risk factors for CVD (cigarette smoking, body mass index (BMI), diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and physical inactivity). Modifiable risk factors for CVD are well-known to be independently associated with hearing impairment,11 29 and potentially confound the associations between SES and hearing loss. Age-at-interview was categorised into four groups (45–54, 55–64, 65–74 and ≥75 years). Government Office Region was grouped into North, Midlands, London and South. Duration of exposure to work-related noise was established by asking participants whether they had ever worked in a place that was so noisy that you had to shout to be heard (response categories: ‘no’, ‘yes, for <1 year’, ‘yes, for at least 1 year but <5 years’, and ‘yes, for 5 years or longer’). Cigarette smoking status categories were current, ex-regular and never. Single measurements of height and weight were taken by trained interviewers using standard protocols. BMI was computed as weight in kg divided by height in metres squared (m2): participants were classified as normal-weight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), overweight (25.0–29.9 kg/m2) or obese (≥30.0 kg/m2). We used two indicators of hyperglycaemia: self-reported physician diagnosis of diabetes, and raised glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c ≥6.5%) irrespective of diagnosis. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg and/or current use of medication taken for the purposes of lowering blood pressure. Total cholesterol was measured in non-fasting blood samples. Dyslipidaemia was defined as total cholesterol ≥5.0 mmol/L and/or current use of lipid-lowering medication. Based on the Short-Form International Physical Activity Questionnaire, participants spending <30 min per week in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity were classed as physically inactive.30 Broader categories of these covariates were used in some cases for the analysis of current hearing aid use due to smaller sample sizes. Age-at-interview was recoded into three categories: 45–64, 65–74 and ≥75 years. Duration of exposure to work-related noise was dichotomised into none and at least some exposure to loud noise.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were sex-specific. Hearing loss prevalence (overall and by severity) was estimated among the overall population and as stratified by demographic characteristics, exposure to work-related noise, CVD risk factors, and SES. Prevalence estimates were directly age-standardised within sex to the English household population using the four age groups described above. Differences in the prevalence of hearing loss across groups were evaluated using the χ2 test. This analysis was repeated to estimate the prevalence of current hearing aid use among those participants with hearing loss.

Logistic regression modelling was used to evaluate the association between SES and hearing loss after adjustment for demographics, exposure to work-related noise and CVD risk factors. Associations were summarised using ORs with 95% CIs. We decided a priori to run separate models for the three indicators of SES rather than estimate a single model to avoid multicollinearity. Two sequential models were fitted. SES and hearing loss associations were age-adjusted (model A), and then further adjusted for region, exposure to work-related noise, and CVD risk factors (model B). To maximise power age was entered in the models as a continuous variable. SES was entered in the models as a categorical variable, with the highest status group as the reference category. We repeated the analyses to evaluate the association between SES and current hearing aid use, with an additional adjustment for the severity of hearing loss. All analyses accounted for the complex survey design, incorporating the nurse-visit weight which accounted for individual non-participation and preserved the national representativeness of the sample. Data set preparation was performed in SPSS V.20.0 (IBM). Statistical analysis was conducted using Stata V.13.1. The HSE 2014 dataset is available via the UK Data Service (http://www.ukdataservice.ac.uk).

Results

Compared with participants with data collected from the nurse-visit stage, participants interviewed in the survey but without data from the nurse-visit were more likely to be in the lowest income tertile (P=0.002), to have no formal educational qualifications (P<0.001), to reside in the most deprived IMD quintile (P<0.001), and to be current cigarette smokers (P=0.011) (online supplementary table 1).

bmjopen-2017-019615supp001.pdf (441.2KB, pdf)

Hearing loss

Table 1 shows the age-standardised estimates of the prevalence of hearing loss. For simplicity, we present only estimates by age, duration of exposure to work-related noise and each indicator of SES in the main text, with the estimates for region and for each CVD risk factor available as online supplementary data. Overall, 26% of men and 20% of women aged ≥45 years had hearing loss defined as >35 dB HL at 3.0 kHz in the better-hearing ear (n=769/3292), equivalent to 5.2 million persons. The prevalence of ‘moderate’ loss (15% men, 12% women) exceeded that of ‘moderately severe or severe’ loss (11% men, 7% women). Hearing loss increased monotonically with age, reaching 67% of men and 58% of women aged ≥75 years. Only among men in the oldest age group did the prevalence of ‘moderately severe or severe’ loss (39%) exceed that of ‘moderate’ loss (29%). Among men, hearing loss was higher among those exposed to work-related noise for ≥5 years (P<0.001), in the lowest income tertile (P=0.005), residing in areas of higher deprivation (P=0.011), and with no formal educational qualifications (P<0.001). Patterns among women were similar but the differences in the prevalence of hearing loss across the SES groups did not reach statistical significance (P=0.077 and P=0.070 for IMD and for educational status, respectively). Of the risk factors for CVD, hearing loss was higher among men and women with doctor-diagnosed diabetes (P<0.001 men; P=0.005 women), with elevated Hb1Ac irrespective of diagnosis (P<0.001 men; P=0.025 women) and among women classed as physically inactive (P=0.028) (online supplementary table 2).

Table 1.

Age-standardised prevalence (%) and SE of hearing loss, persons aged 45 years and over, HSE 2014

| Characteristics | Men | Women | ||||||||

| N | Hearing loss % (SE)* | Moderate % (SE)† | Moderate to severe % (SE)‡ | P value§ | N | Hearing loss % (SE)* | Moderate % (SE)† | Moderate to severe % (SE)‡ | P value§ | |

| N | 1485 | 425 | 244 | 181 | 1807 | 344 | 217 | 127 | ||

| All | 1485 | 26.2 (1.2) | 15.2 (1.0) | 11.0 (0.9) | – | 1807 | 19.6 (1.0) | 12.2 (0.8) | 7.4 (0.7) | |

| Age group | ||||||||||

| 45–54 | 420 | 8.0 (1.5) | 7.0 (1.4) | 1.0 (0.5) | <0.001 | 560 | 3.1 (0.9) | 2.3 (0.7) | 0.7 (0.4) | <0.001 |

| 55–64 | 401 | 17.0 (2.0) | 10.9 (1.7) | 6.1 (1.2) | 446 | 10.6 (1.6) | 8.6 (1.4) | 2.0 (0.7) | ||

| 65–74 | 402 | 37.0 (2.5) | 23.8 (2.2) | 13.3 (2.0) | 476 | 20.4 (1.8) | 14.5 (1.6) | 5.9 (1.1) | ||

| ≥75 | 262 | 67.3 (3.2) | 28.6 (2.8) | 38.7 (3.1) | 325 | 57.9 (2.9) | 30.6 (2.5) | 27.3 (2.6) | ||

| Duration of work-related noise exposure | ||||||||||

| None | 819 | 22.2 (1.6) | 13.4 (1.3) | 8.9 (1.2) | <0.001 | 1468 | 18.6 (1.1) | 12.1 (0.9) | 6.5 (0.7) | 0.091 |

| <5 years | 226 | 24.6 (2.9) | 11.1 (2.3) | 13.5 (2.4) | 128 | 18.8 (3.8) | 10.8 (3.0) | 7.9 (2.7) | ||

| ≥5 years | 434 | 35.1 (2.5) | 21.5 (2.1) | 13.6 (1.7) | 210 | 25.4 (3.0) | 13.6 (2.4) | 11.8 (2.2) | ||

| Income tertiles | ||||||||||

| Highest | 491 | 21.3 (2.5) | 13.1 (2.0) | 8.2 (1.7) | 0.005 | 484 | 16.5 (2.3) | 11.0 (1.9) | 5.5 (1.4) | 0.413 |

| Middle | 458 | 28.6 (2.2) | 16.7 (1.9) | 12.0 (1.5) | 562 | 19.3 (1.8) | 11.9 (1.4) | 7.4 (1.2) | ||

| Lowest | 305 | 32.9 (2.8) | 19.8 (2.2) | 13.1 (2.0) | 417 | 20.1 (1.9) | 13.1 (1.6) | 7.0 (1.2) | ||

| Index of Multiple Deprivation quintiles | ||||||||||

| Least deprived | 369 | 21.4 (2.2) | 11.0 (1.8) | 10.3 (1.7) | 0.011 | 448 | 18.6 (2.1) | 11.4 (1.5) | 7.2 (1.4) | 0.077 |

| 2 | 340 | 23.0 (2.4) | 13.2 (1.8) | 9.8 (1.7) | 407 | 17.6 (1.7) | 11.5 (1.5) | 6.1 (1.2) | ||

| 3 | 311 | 27.2 (2.7) | 17.1 (2.3) | 10.1 (1.8) | 392 | 17.5 (2.1) | 10.9 (1.7) | 6.6 (1.5) | ||

| 4 | 255 | 32.6 (2.9) | 18.2 (2.5) | 14.4 (2.2) | 312 | 19.8 (2.6) | 10.6 (2.1) | 9.2 (1.7) | ||

| Most deprived | 210 | 30.2 (3.3) | 18.0 (2.6) | 12.2 (2.6) | 248 | 26.3 (2.7) | 18.4 (2.4) | 7.9 (1.7) | ||

| Education status | ||||||||||

| Degree or higher | 344 | 20.1 (2.6) | 12.3 (2.1) | 7.8 (1.7) | <0.001 | 309 | 14.5 (3.5) | 7.8 (2.2) | 6.7 (2.5) | 0.070 |

| Below degree | 733 | 23.2 (1.8) | 12.8 (1.3) | 10.4 (1.4) | 941 | 18.4 (1.6) | 12.1 (1.2) | 6.4 (1.1) | ||

| No qualifications | 407 | 40.1 (3.0) | 26.5 (2.9) | 13.7 (1.7) | 555 | 23.6 (2.1) | 14.7 (1.8) | 8.9 (1.1) | ||

*Hearing loss: >35 dB HL at 3.0 kHz (tone not heard at 35 dB HL).

†Moderate loss: >35 to 54 dB HL (tone not heard at 35 dB HL, but heard at 55 and at 75 dB HL).

‡Moderately severe or severe loss: >55 dB HL (tone not heard at 35 and at 55 dB HL, but may or may not have heard the tone at 75 dB HL).

§Prevalence of hearing loss (>35 dB HL at 3.0 kHz in the better hearing ear) across the categories of each variable (age group, duration of work-related noise exposure, income tertiles, Index of Multiple Deprivation quintiles and highest educational attainment) were compared using the χ2 tests. No adjustment to the P values for multiple comparisons was made.

dB, decibel; HL, hearing level; HSE, health survey for England.

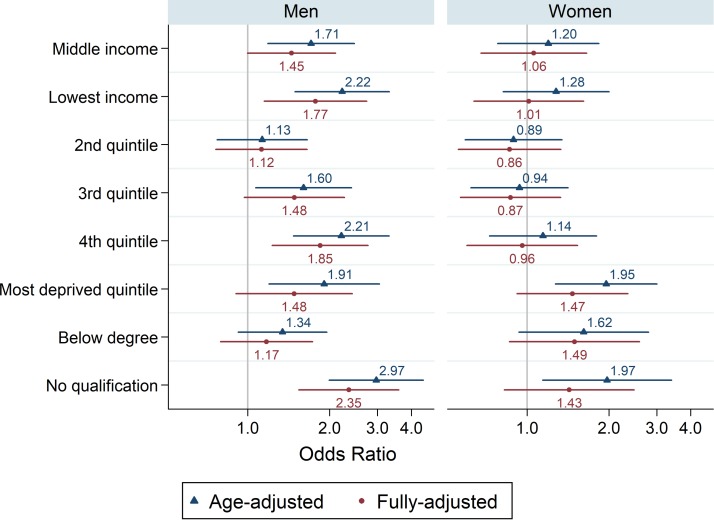

Figure 2 shows the associations between SES and hearing loss (expressed as ORs) after age (model A) and additional adjustment for region, duration of exposure to work-related noise and CVD risk factors (model B). Among men, the multivariable-adjusted associations were partly attenuated: nevertheless, the multivariable-adjusted odds of hearing loss showed a strong socioeconomic gradient. The odds of hearing loss were almost two times as high for men in the lowest versus the highest income tertile (OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.15 to 2.74) and were over two times as high for men with no formal educational qualifications versus those with at least a degree (OR 2.35, 95% CI 1.54 to 3.59). For women, the association between SES and hearing loss did not reach statistical significance. For example, the odds of hearing loss were 1.4 times higher for women with no formal educational qualifications versus those with at least a degree (OR 1.43, 95% CI 0.83 to 2.48).

Figure 2.

Association between socioeconomic status (SES) and hearing loss in middle-aged and older adults. Indicators of SES were equivalised household income tertiles (highest tertile as reference), Index of Multiple Deprivation quintiles (least deprived) and highest educational attainment (degree or higher). Lines represent OR (outcome=hearing loss) and its 95% CI. Model A (triangles): adjusted for age. Model B (circles): adjusted for age, exposure to work-related noise, region and cardiovascular disease risk factors (smoking, body mass index, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and physical inactivity).

Current hearing aid use

Among participants with hearing loss, 30% of men and 27% of women wore hearing aids nowadays (n=264/769; table 2). Lower proportions had tried hearing aids in the past but did not use a hearing aid nowadays (7% men, 10% women): higher proportions had never tried a hearing aid (63% men, 64% women) (data not shown). Current use of a hearing aid for persons with ‘moderately severe or severe’ loss (53% men, 47% women) exceeded that for persons with ‘moderate’ loss (18% men, 19% women) (P<0.001 men; P=0.004 women). Current hearing aid use increased monotonically with age but was confined to the minority, reaching close to 40% for participants aged ≥75 years.

Table 2.

Age-standardised prevalence (%) and SE of current hearing aid use among persons with hearing loss, persons aged 45 years and over, HSE 2014

| Characteristics | Men | Women | ||||

| N | Hearing aid use % (SE) | P value* | N | Hearing aid use % (SE) | P value* | |

| N | 425 | 29.7 (3.1) | 344 | 26.9 (3.3) | ||

| Severity of loss | ||||||

| Moderate† | 244 | 17.8 (3.2) | <0.001 | 217 | 19.1 (3.5) | 0.002 |

| Moderate to severe‡ | 181 | 52.9 (6.3) | 127 | 47.1 (8.7) | ||

| Age group | ||||||

| 45–64 | 101 | 25.4 (4.6) | 0.056 | 63 | 21.2 (5.1) | 0.035 |

| 65–74 | 147 | 34.3 (4.3) | 94 | 31.4 (4.9) | ||

| ≥75 | 177 | 40.2 (3.7) | 187 | 39.1 (3.7) | ||

| Duration of work-related noise exposure | ||||||

| None | 250 | 26.1 (3.9) | 0.234 | 287 | 25.3 (3.6) | 0.296 |

| Some | 173 | 33.5 (4.9) | 56 | 35.5 (9.4) | ||

| Income tertiles | ||||||

| Highest | 84 | 36.0 (6.5) | 0.548 | 54 | 24.7 (6.5) | 0.900 |

| Middle | 149 | 31.2 (5.5) | 105 | 28.6 (5.8) | ||

| Lowest | 118 | 26.0 (6.1) | 90 | 26.0 (7.0) | ||

| Index of Multiple Deprivation quintiles | ||||||

| Least deprived 1 and 2 | 179 | 29.8 (5.3) | 0.812 | 158 | 29.1 (5.2) | 0.615 |

| Quintile 3 | 101 | 33.5 (8.0) | 66 | 29.3 (6.6) | ||

| Most deprived 4 and 5 | 145 | 27.9 (4.6) | 120 | 22.6 (5.6) | ||

| Education status | ||||||

| O level or above | 227 | 32.3 (4.2) | 0.354 | 151 | 28.0 (4.3) | 0.654 |

| No qualifications | 198 | 26.3 (4.6) | 192 | 24.7 (5.6) | ||

*Prevalence of current hearing aid use across the categories of each variable (age group, duration of work-related noise exposure, income tertiles, Index of Multiple Deprivation quintiles and highest educational attainment) were compared using the χ2 test. No adjustment to the P values for multiple comparisons was made.

†Moderate loss: >35 to 54 dB HL (tone not heard at 35 dB HL, but tone heard at 55 and 75 dB HL).

‡Moderately severe or severe loss: >55 dB HL (tone not heard at 35 and 55 dB HL, but may or may not have heard the tone at 75 dB HL).

dB, decibel; HL, hearing level; HSE, health survey for England.

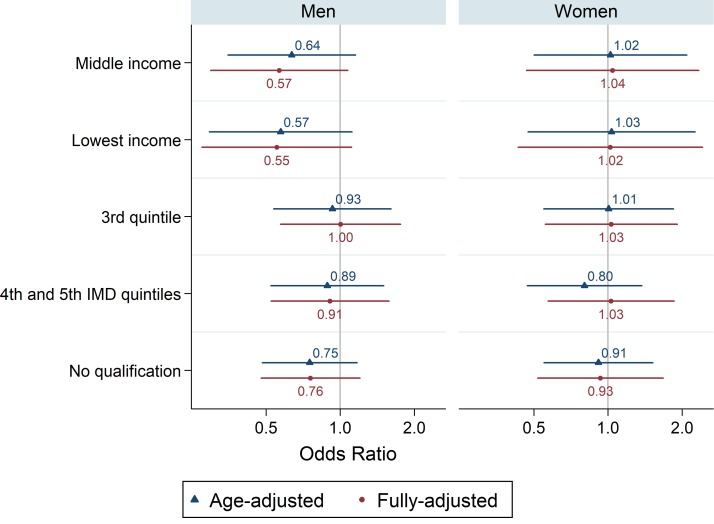

Differences in current hearing aid use by population subgroups were typically minor (P>0.05), with the exception of lower use of a hearing aid nowadays among women classed as physically inactive (P=0.003) (online supplementary table 3). Lower use among participants reporting doctor-diagnosed diabetes (n=143/768) did not reach statistical significance (P=0.101 men; P=0.077 women). Figure 3 shows the associations between SES and current hearing aid use after age-adjustment (model A) and full-adjustment (model B). Compared with men in the highest income tertile, the multivariable-adjusted odds of using a hearing aid nowadays were lower for men in the middle (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.99) and the lowest (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.97) income tertiles. Among men, area deprivation (as measured by IMD) and highest educational attainment were associated with current hearing aid use in the same direction (ie, lower levels of use in the lower SES groups) but the ORs did not reach statistical significance. For women, SES was not associated with current hearing aid use.

Figure 3.

Association between socioeconomic status (SES) and current hearing aid use in middle-aged and older adults with hearing loss. Indicators of SES were equivalised household income tertiles (highest tertile as reference), Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) quintiles (least deprived Q1 and Q2) and highest educational attainment (O level and above). Lines represent OR (outcome=hearing aid use) and its 95% CI. Model A (triangles): adjusted for age. Model B (circles): adjusted for: age, severity of hearing loss, exposure to work-related noise, region and cardiovascular disease risk factors (smoking, body mass index, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and physical inactivity).

Discussion

In this nationally representative sample of community-dwelling persons aged 45 years and over, >1 in four persons had a level of hearing loss that would benefit from hearing aid use. However, <1 in three persons with hearing loss reported using a hearing aid nowadays, suggesting a significant level of unmet need. The burden of hearing loss fell highest among persons in the lowest SES groups, especially among men, suggesting hearing loss as a source of socioeconomic inequalities in health. Even after adjustment for the severity of hearing loss, hearing aid use was evidently lower for men in the middle-income and low-income groups compared with their high-income counterparts.

Comparisons with previous studies are difficult due to differences in the age range of participants.6 Considerable heterogeneity also exists in the definition and the measurement of hearing loss.31 WHO defines adult disabling hearing impairment as a permanent unaided hearing threshold for the better-hearing ear of ≥41 dB HL (averaged over 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 kHz).32 Using this definition, disabling hearing loss was estimated to affect 360 million people worldwide in 2012 (>5% of the global population).33 The Global Burden of Disease Hearing Loss Expert Group uses a threshold of >35 dB HL for all age groups, and equates ‘unilateral hearing impairment’ with ‘bilateral mild hearing impairment’.7 The estimated global prevalence of hearing loss using this alternative definition was 12% for men and 10% for women aged ≥15 in 2008.7 Analysis of HSE 2014 data by the same authors of the present study found that 13% of adults (14% men, 12% women) had loss of >35 dB HL at 3.0 kHz in the better-hearing ear.17 Our findings of differences in the burden of hearing loss agree with other population-based studies in which the prevalence of hearing loss was higher for men than women,6–8 34–37 increased monotonically with age,6–9 21 34–36 38 increased with longer exposure to occupational noise,8 co-existed with CVD risk factors such as diabetes,6 8–11 and was higher in the lowest SES groups,6 9 35 36 38 39 especially for men.12 In contrast to other studies,6 8–10 hearing loss did not vary in the present study by current smoking status.

Other studies have shown similar or lower levels of hearing aid use among persons with hearing loss. Using the Digit Triplet Test, 21.5% of UK Biobank participants aged 40–69 years with ‘poor’ speech recognition in noise testing reported using a hearing aid.38 Based on the 1999–2006 US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, hearing aid use among participants aged 50 years and older with hearing loss was 14.2%.15 Our findings of subgroup differences in levels of hearing aid use are consistent with other studies which showed that use increases with age15 40 and with the severity of hearing loss.15 19 Our finding of lower utilisation among men in the lowest SES groups, independent of the severity of hearing loss, is also consistent with other studies.18 19 38 40 41

Associations between SES and hearing loss likely involve multiple simultaneous pathways35 including other concomitant factors of lower SES such as educational and employment factors (including exposure to work-related noise), and modifiable lifestyle factors.8 While occupational noise is now limited and generally well-controlled in the UK,42 past exposure may have had serious long-term consequences for hearing in middle-age and older-age.

It remains unclear the extent to which hearing loss is a driver of low SES or whether low SES is a driver of hearing loss.35 First, analysis in Finland showed that hearing loss early in life—with its detrimental impact on educational attainment in adolescence—can be a driver of low SES in young adulthood through fewer opportunities for entering into higher education and through more frequent spells of unemployment.43 Second, longitudinal studies have suggested low SES to be a key driver of hearing loss in middle-to-older age through factors such as working in jobs with a greater potential for exposure to damaging levels of noise. For example, analysis of the Beaver Dam Eye Study showed that the development of incident hearing loss was more likely among participants with lower levels of educational attainment and among those participants who worked in industrial occupations versus management and professional positions.37 44

The diabetes–hearing loss associations found in our study are in agreement with a recent meta-analysis.45 Explanations for the association between diabetes and hearing loss include the microvascular and neuropathic complications that affect diabetics in multiple organ systems which may also affect the inner ear.46 47 This study confirms the low level of current hearing aid use, especially among men in the lowest SES groups. Previous studies have demonstrated non-financial barriers to uptake and use, with self-recognition of hearing problems being the strongest factor.48 Low take up and use are typically attributed to a perception of hearing loss being an expected consequence of ageing. Non-audiological drivers for older adults with hearing impairment consulting a health professional and/or to use hearing aids included a positive attitude to hearing aids (their own and from significant others) and self-efficacy about hearing aids (eg, placement and battery removal).49 Although treatment and hearing aid provision is financially supported in the UK through the National Health Service, persons in the lower SES groups use specialist health services less frequently than those in higher SES groups.50

The main strength of this study was the use of valid screening audiometry data within a nationally representative health examination survey. Data from a hearing test overcomes the underestimation of socioeconomic inequalities in health that are typically associated with self-reports.51 Other analyses of HSE 2014 showed that socioeconomic inequalities in hearing were most apparent using the data from the audiometric screening device but not from the self-report data,17 partly reflecting differences in levels of expectations and differences in levels of awareness of adverse health conditions.52 This study also has a number of limitations. Differences in the propensity to respond at the nurse-visit may have weakened the sample’s representativeness and reduced the generalisability of our findings, but the use of statistical weights to account for the biases in individual participation would have mitigated this to a considerable extent. The estimates of hearing loss prevalence are conservative due to the exclusion of: (1) the institutionalised population, (2) individuals with a cochlear implant or with a current ear infection and (3) the exclusion of an unknown number of individuals with conditions such as deafness that were judged to impede interviewer–participant communication. The relatively small number of participants with hearing loss may have resulted in our analyses of current hearing aid use to be underpowered to detect differences among subgroups. For the same reason, we were unable to examine differences in usage among subgroups stratified by the severity of hearing loss. Insufficient numbers meant that we were unable to provide separate reliable estimates for minority ethnic groups. Our findings could have been influenced by unmeasured confounders such as the duration of exposure to non-occupational noise. Lastly, since we used cross-sectional data, we were unable to assess the temporal relationship between SES and hearing, and so could not establish causality.

In conclusion, hearing loss is highly prevalent, affecting more than one in four men and affecting one in five women. However, less than one in three persons with hearing loss reported using a hearing aid nowadays, suggesting a significant level of unmet need. While the burden of hearing loss falls highest among persons, but especially men, in the lowest SES groups, use of hearing aids is demonstrably lower. Initiatives to detect hearing loss early, and the increased uptake of hearing aids, may provide substantial public health benefits and reduce socioeconomic inequalities in health.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SS, JB, AD and JSM were responsible for developing the design of the study. SS was responsible for conducting the analyses, interpreting the results and drafting the manuscript. SS, JB, AD and JSM critically revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Oxford A Research Ethics Committee (12/SC/0317).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The Health Survey for England 2014 dataset is available via the UK Data Service (http://www.ukdataservice.ac.uk). Statistical code is available from the corresponding author at s.scholes@ucl.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:293–9. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin FR, Metter EJ, O’Brien RJ, et al. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol 2011;68:214–20. 10.1001/archneurol.2010.362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surprenant AM, DiDonato R. Community-dwelling older adults with hearing loss experience greater decline in cognitive function over time than those with normal hearing. Evid Based Nurs 2014;17:60–1. 10.1136/eb-2013-101375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Prevention of noise-induced hearing loss. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olusanya BO, Neumann KJ, Saunders JE. The global burden of disabling hearing impairment: a call to action. Bull World Health Organ 2014;92:367–73. 10.2471/BLT.13.128728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrawal Y, Platz EA, Niparko JK. Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1522–30. 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens G, Flaxman S, Brunskill E, et al. Global and regional hearing impairment prevalence: an analysis of 42 studies in 29 countries. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:146–52. 10.1093/eurpub/ckr176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoffman HJ, Dobie RA, Losonczy KG, et al. Declining prevalence of hearing loss in US adults aged 20 to 69 years. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017;143:274–85. 10.1001/jamaoto.2016.3527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rigters SC, Metselaar M, Wieringa MH, et al. Contributing determinants to hearing loss in elderly men and women: results from the population-based Rotterdam study. Audiol Neurootol 2016;21(Suppl 1):10–15. 10.1159/000448348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Agrawal Y, Platz EA, Niparko JK. Risk factors for hearing loss in US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999 to 2002. Otol Neurotol 2009;30:139–45. 10.1097/MAO.0b013e318192483c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim M-B, et al. Diabetes mellitus and the incidence of hearing loss: a cohort study. Int J Epidemiol 2017;46:716–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helvik AS, Krokstad S, Tambs K. Socioeconomic inequalities in hearing loss in a healthy population sample: The HUNT Study. Am J Public Health 2009;99:1376–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2007.133215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peracino A, Pecorelli S. The epidemiology of cognitive impairment in the aging population: implications for hearing loss. Audiol Neurootol 2016;21(Suppl 1):3–9. 10.1159/000448346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Popelka MM, Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, et al. Low prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults with hearing loss: the Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 1998;46:1075–8. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb06643.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chien W, Lin FR. Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Arch Intern Med 2012;172:292–3. 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartley D, Rochtchina E, Newall P, et al. Use of hearing aids and assistive listening devices in an older Australian population. J Am Acad Audiol 2010;21:642–53. 10.3766/jaaa.21.10.4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scholes S, Mindell J. Hearing : Craig R, Mindell J, Health Survey for England 2014 Volume 1 health, social care and lifestyles. Leeds, UK: Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nieman CL, Marrone N, Szanton SL, et al. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in hearing health care among older Americans. J Aging Health 2016;28:68–94. 10.1177/0898264315585505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Helvik AS, Krokstad S, Tambs K. How sociodemographic and hearing related factors were associated with use of hearing aid in a population-based study: the HUNT study. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord 2016;16:8 10.1186/s12901-016-0028-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mamo SK, Nieman CL, Lin FR. Prevalence of untreated hearing loss by income among older adults in the United States. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2016;27:1812–8. 10.1353/hpu.2016.0164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davis AC. The prevalence of hearing impairment and reported hearing disability among adults in Great Britain. Int J Epidemiol 1989;18:911–7. 10.1093/ije/18.4.911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis A. Hearing in adults. London: Whurr, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mindell J, Biddulph JP, Hirani V, et al. Cohort profile: the health survey for England. Int J Epidemiol 2012;41:1585–93. 10.1093/ije/dyr199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parving A, Sørup Sørensen M, Christensen B, et al. Evaluation of a hearing screener. Audiol Med 2008;6:115–9. 10.1080/16513860801995633 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fellizar-Lopez KR, Abes GT, Reyes-Quintos M, et al. Accuracy of siemens hearcheckΤΜ navigator as a screening tool for hearing loss. Philipp J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2011;26:10–15. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Davis A, Smith P, Ferguson M, et al. Acceptability, benefit and costs of early screening for hearing disability: a study of potential screening tests and models. Health Technol Assess 2007;11:1–294. 10.3310/hta11420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Office for National Statistics. Population estimates for UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: mid-2014 and mid-2013. 2015. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/2015-06-25

- 28.Department for Communities and Local Government. The English Indices of deprivation 2010. London: Department for Communities and Local Government, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fischer ME, Schubert CR, Nondahl DM, et al. Subclinical atherosclerosis and increased risk of hearing impairment. Atherosclerosis 2015;238:344–9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.12.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scholes S, Bridges S, Ng Fat L, et al. Comparison of the physical activity and sedentary behaviour assessment questionnaire and the short-form international physical activity questionnaire: an analysis of Health Survey for England data. PLoS One 2016;11:e0151647 10.1371/journal.pone.0151647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roth TN, Hanebuth D, Probst R. Prevalence of age-related hearing loss in Europe: a review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2011;268:1101–7. 10.1007/s00405-011-1597-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.World Health Organization. Prevention of blindness and deafness. Grades of hearing impairment. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization. Global estimates on prevalence of hearing loss. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goman AM, Lin FR. Prevalence of hearing loss by severity in the United States. Am J Public Health 2016;106:1820–2. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Emmett SD, Francis HW. The socioeconomic impact of hearing loss in U.S. adults. Otol Neurotol 2015;36:545–50. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cruickshanks KJ, Wiley TL, Tweed TS, et al. Prevalence of hearing loss in older adults in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. The Epidemiology of Hearing Loss Study. Am J Epidemiol 1998;148:879–86. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cruickshanks KJ, Nondahl DM, Tweed TS, et al. Education, occupation, noise exposure history and the 10-yr cumulative incidence of hearing impairment in older adults. Hear Res 2010;264(1-2):3–9. 10.1016/j.heares.2009.10.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dawes P, Fortnum H, Moore DR, et al. Hearing in middle age: a population snapshot of 40- to 69-year olds in the United Kingdom. Ear Hear 2014;35:e44–e51. 10.1097/AUD.0000000000000010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ecob R, Sutton G, Rudnicka A, et al. Is the relation of social class to change in hearing threshold levels from childhood to middle age explained by noise, smoking, and drinking behaviour? Int J Audiol 2008;47:100–8. 10.1080/14992020701647942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bainbridge KE, Ramachandran V. Hearing aid use among older U.S. adults; the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005-2006 and 2009-2010. Ear Hear 2014;35:289–94. 10.1097/01.aud.0000441036.40169.29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis AC. Epidemiological profile of hearing impairments: the scale and nature of the problem with special reference to the elderly. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl 1990;476:23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lutman M, Davis AC, Ferguson M. Epidemiological evidence for the effectiveness of the noise at work regulations. Sudbury, UK: Health and Safety Executive, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Järvelin MR, Mäki-Torkko E, Sorri MJ, et al. Effect of hearing impairment on educational outcomes and employment up to the age of 25 years in northern Finland. Br J Audiol 1997;31:165–75. 10.3109/03005364000000019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cruickshanks KJ, Tweed TS, Wiley TL, et al. The 5-year incidence and progression of hearing loss: the epidemiology of hearing loss study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2003;129:1041–6. 10.1001/archotol.129.10.1041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Horikawa C, Kodama S, Tanaka S, et al. Diabetes and risk of hearing impairment in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:51–8. 10.1210/jc.2012-2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Friedman SA, Schulman RH, Weiss S. Hearing and diabetic neuropathy. Arch Intern Med 1975;135:573–6. 10.1001/archinte.1975.00330040085014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukushima H, Cureoglu S, Schachern PA, et al. Effects of type 2 diabetes mellitus on cochlear structure in humans. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;132:934–8. 10.1001/archotol.132.9.934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Knudsen LV, Oberg M, Nielsen C, et al. Factors influencing help seeking, hearing aid uptake, hearing aid use and satisfaction with hearing aids: a review of the literature. Trends Amplif 2010;14:127–54. 10.1177/1084713810385712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meyer C, Hickson L, Lovelock K, et al. An investigation of factors that influence help-seeking for hearing impairment in older adults. Int J Audiol 2014;53(Suppl 1):S3–17. 10.3109/14992027.2013.839888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Capewell S, Graham H. Will cardiovascular disease prevention widen health inequalities? PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000320 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chatterji P, Joo H, Lahiri K. Examining the education gradient in chronic illness. Educ Econ 2015;23:735–50. 10.1080/09645292.2014.944858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Johnston DW, Propper C, Shields MA. Comparing subjective and objective measures of health: Evidence from hypertension for the income/health gradient. J Health Econ 2009;28:540–52. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2009.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-019615supp001.pdf (441.2KB, pdf)