Abstract

Objective

Animal studies showed that male subjects had lower activity of immune response to infections than female subjects, which may increase the risk of the development of tuberculosis in male population. This study intended to investigate the risk of incident tuberculosis in male and female adults in Taiwan.

Design

This is a retrospective cohort study.

Setting

The present analyses used data of Taiwan National Health Interview Survey 2001, 2005 and 2009, National Register of Deaths Dataset, and National Health Insurance Research Database from 2000 to 2013.

Participants

A total of 43 424 subjects with a mean age of 43.04 years were analysed.

Primary outcome measures

Incidence of tuberculosis.

Results

During 381 561 person-years of follow-up period, incident tuberculosis was recognised in 268 individuals. The incidence rates of tuberculosis were 97.56 and 43.24 per 100 000 person-years among male and female participants, respectively. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing male and female subjects showed statistical significance (log-rank test, P value<0.01). After adjusting for subjects’ demographics and comorbidities, men showed increased risks of incident tuberculosis (adjusted HR, 1.68; 95% CI 1.21 to 2.34; P value<0.01) compared with women. On subgroup analysis, after stratifying by age, smoking and alcohol use, men had a higher risk of incident tuberculosis than women in all patient subgroups, except those who were current smokers.

Conclusions

This study suggests that men had a higher risk of incident tuberculosis than women. Future tuberculosis control programmes should particularly target the male population.

Keywords: tuberculosis, cohort study, sex

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used the large national health surveys to access a representative cohort and was cross-linked with the National Health Insurance Research Database; therefore, the possibility of selection bias can be excluded.

The National Health Interview Survey was planned and accomplished by a well-experienced national survey group, using a standard interview process.

Detailed personal information was collected, which allowed us to adjust for the major risk factors of tuberculosis in the analysis.

The definition of tuberculosis relied on the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes and medication prescription history of antituberculosis drugs, and the outcome of incident tuberculosis may be misclassified.

Almost all our subjects were Taiwanese and the external validity of the results should be a concern.

Introduction

Tuberculosis remains one of the most widespread infectious diseases around the world. About one-third of the global population is latently infected by tuberculosis.1 In 2016, it was estimated that there are 10.4 million cases of tuberculosis in the world; of those, 6.8 million (65%) were male patients.2

In Taiwan, tuberculosis had the highest annual number of incident cases in all reported infectious diseases for decades.3 Since 2006, the Centers for Disease Control of Taiwan implemented a directly observed therapy, a short-course programme, with the aim of reducing the incidence of tuberculosis by half by 2015. As a result, the incidence of tuberculosis dropped from 72.5/100 000 in 2005 to 45.7/100 000 in 2015.3 Nevertheless, 10 711 new-onset tuberculosis cases remained in 2015 in Taiwan.

Men and women may have differences in susceptibility to infectious diseases. Animal studies showed that male mice have a lower activity of immune response to infections than female mice.4 Clinical studies also revealed that men have decreased CD3+ and CD4+ T cell counts and T helper type I reactions as compared with women during infectious diseases.5 A previous report indicated that sex hormone may be a significant factor for the differences in susceptibility to infectious diseases between men and women.6 Prior studies showed that testosterone could impair macrophage activation7 and play a detrimental role in the development of tuberculosis.8 In contrast, oestrogens are proinflammatory mediators’ inducer that stimulates the production of tumour necrosis factor-α9 and interacts with the Interferon -γ promoter.10

Tuberculosis is one of the most widespread infectious diseases around the world. Understanding sex-based differences on the risk of incident tuberculosis would be greatly beneficial for intensive tuberculosis prevention programmes. We therefore conducted this retrospective cohort study to determine the risk of incident tuberculosis by using a national survey data in Taiwan.

Methods

Study subjects and data source

The study population was selected from three rounds of a large general survey in Taiwan, namely the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), which was performed in 2001, 2005 and 2009. A systematic, multistage, stratified sampling design based on the degree of suburbanisation, geographical setting and local administrative boundaries was used to pick up a representative sample of the general population in Taiwan.11 Well-trained interviewers collected the data by an identical face-to-face interview. The survey data provide information on participants’ sociodemographic and lifestyle behaviours. The National Health Insurance (NHI) data set contains all inpatient and outpatient medical records, and the diagnosis and procedures were recorded using the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes. Deaths were confirmed by examining the death certificate database of Taiwan. Subjects under the age of 18 years were excluded. Subjects who were diagnosed with tuberculosis (ICD-9-CM codes 010–018) before the interview were excluded. All study participants were followed from the time of the NHIS interview until a diagnosis of tuberculosis, death or 31 December 2013.

Main explanatory variable and outcome variable

The main explanatory variable was sex. Information on participants’ sex was collected during the NHIS interview. This study identified new onset of tuberculosis cases by linking the NHIS data set to the NHI data set. An incident tuberculosis case was defined as the presence of tuberculosis diagnosis coded (ICD-9-CM codes 010–018) and the treatment of more than two antituberculosis medications, such as isoniazid, ethambutol, rifampin and pyrazinamide, for more than 4 weeks.12

Potential confounding variables

Risk factors for tuberculosis, which were identified in previous studies, were assessed in our analyses13; these included the individuals’ sociodemographic characteristics (age, educational level, marital status, household income, smoking habit and alcohol consumption) and comorbidities. Marital status was classified into single, married/cohabiting and widowed/divorced/separated. Household income level was grouped in tertiles: low (US$968/month), moderate (US$968–2258/month) and high (>US$2258/month). Smoking habit was categorised as never, former and current smokers. Alcohol consumption included never, less than once a week and more than once a week. The presence of comorbidities in patients was determined according to the ICD-9-CM codes. The comorbidities included diabetes (ICD-9-CM code 250), chronic kidney disease (ICD-9-CM codes 580–587), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ICD-9-CM codes 491, 492 and 496), asthma (ICD-9-CM code 493) and cancer (ICD-9-CM codes 140–208). A comorbidity was identified if the condition occurred in three or more outpatient visits or an inpatient setting admission.14

Statistical analysis

The characteristics of the male and female participants were analysed. The two-sample t-test was used for comparisons of continuous data between male and female groups. Categorical data were analysed using the Pearson’s χ2 test. The incidence of tuberculosis per 100 000 person-years was calculated according to sex. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to address and draw the incidence of tuberculosis over time by sex with a log-rank test. Univariate Cox regression model was used to evaluate the crude associations of sex and other potential confounding variables with active tuberculosis by calculating the HRs and 95% CIs. Multivariable Cox regression model was used to assess the independent association between gender and active tuberculosis after adjusting for potential confounders. Finally, stratified analyses were conducted after stratifying the patients according to age, alcohol use and smoking status. Data analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4 software.

Results

A total of 48 604 adult individuals participated in the three rounds of the NHIS in Taiwan. After excluding those with diagnosed and treated tuberculosis (n=273), unknown sex (n=1) and incomplete data (n=4906), the remaining 43 424 patients were included in our analysis. The overall mean (SD) age was 43.1 (16.6) years, 49.7% of the subjects were male, and the mean (SD) follow-up time was 8.8 (3.5) years. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics and comorbidities between male and female participants. As compared with female participants, male participants had a higher proportion of current and ever smoking. Moreover, male participants had a higher percentage of chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cancer, but had a lower proportion of asthma than female participants.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n=43 424)

| Characteristics | Men, n=21 597 n (%) |

Women, n=21 827 n (%) |

P value |

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 42.8 (16.7) | 43.3 (16.5) | <0.01 |

| Marriage status | |||

| Married/cohabiting | 13 395 (62.0) | 13 476 (61.7) | <0.01 |

| Single | 6870 (31.8) | 5173 (23.7) | |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 1332 (6.2) | 3178 (14.6) | |

| Education | |||

| Elementary or below | 4163 (19.3) | 6623 (30.3) | <0.01 |

| Junior/senior high | 10 394 (48.1) | 8990 (41.2) | |

| College or above | 7040 (32.6) | 6214 (28.5) | |

| Household income | |||

| Low (<US$968/month) | 4858 (22.5) | 5474 (25.1) | <0.01 |

| Moderate (US$968–2258/month) | 9396 (43.5) | 9363 (42.9) | |

| High (>US$2258/month) | 7343 (34.0) | 6990 (32.0) | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never | 9466 (43.8) | 20 219 (92.6) | <0.01 |

| Current | 9780 (45.3) | 1294 (5.9) | |

| Ever | 2351 (10.9) | 314 (1.5) | |

| Alcohol use | |||

| None | 9854 (45.6) | 16 979 (77.8) | |

| Less than once a week | 5659 (26.2) | 3537 (16.2) | <0.01 |

| More than once a week | 6084 (28.2) | 1311 (6.0) | |

| Comorbidity | |||

| Diabetes | 3268 (15.1) | 3264 (15.0) | 0.60 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 665 (3.1) | 524 (2.4) | <0.01 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3379 (15.7) | 3042 (13.9) | <0.01 |

| Asthma | 1651 (7.6) | 2038 (9.3) | <0.01 |

| Cancer | 1586 (7.3) | 1418 (6.5) | <0.01 |

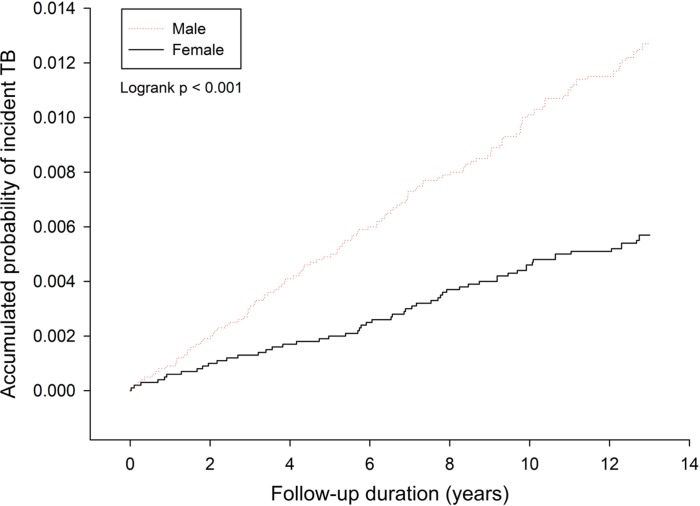

Among 43 424 study subjects, new-onset tuberculosis cases were noted in 268 individuals after the NHIS interview, including 185 (0.86%) male participants and 83 (0.83%) female participants. The incidence rates of tuberculosis were 97.56 and 43.24 per 100 000 person-years among male and female participants, respectively (P<0.01). Kaplan-Meier curves comparing men and women revealed statistical significance (log-rank test, P<0.01) (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence rate for incident tuberculosis (TB) by sex.

As compared with female participants, the relative risk of incident tuberculosis was higher among male subjects (HR=2.25; 95% CI 1.74 to 2.92; P<0.01) in univariate analysis. Other factors associated with new-onset tuberculosis were older age, being widowed/divorced/separated, current and ever smoking, alcohol consumption more than once a week, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma and cancer (table 2). Those with higher education levels and higher household income levels had decreased risks of incident tuberculosis (table 2). After controlling for demographics and comorbidities, men had higher risks of new-onset tuberculosis than women (HR=1.68; 95% CI 1.21 to 2.34; P<0.01) (table 2).

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards analyses of risk of incident tuberculosis (n=43 424; 241 tuberculosis cases)

| Characteristics | Subjects, n (% in column) | Tuberculosis, n (% in row) | Univariate analysis HR (95% CI) | Multivariate analysis AHR (95% CI) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 21 827 (50.26) | 83 (0.38) | Ref | Ref |

| Male | 21 597 (49.74) | 185 (0.86) | 2.25 (1.74 to 2.92) | 1.68 (1.21 to 2.34) |

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 1.67 (1.55 to 1.79) | 1.44 (1.30 to 1.60) | ||

| Marriage status | ||||

| Married/cohabiting | 26 871 (61.88) | 189 (0.70) | Ref | Ref |

| Single | 12 043 (27.73) | 30 (0.25) | 0.35 (0.24 to 0.51) | 1.05 (0.68 to 1.62) |

| Widowed/divorced/separated | 4510 (10.39) | 49 (1.09) | 1.75 (1.28 to 2.40) | 1.14 (0.82 to 1.60) |

| Education | ||||

| Elementary or below | 10 786 (24.84) | 140 (1.30) | Ref | Ref |

| Junior/senior high | 19 384 (44.64) | 94 (0.48) | 0.36 (0.28 to 0.47) | 0.81 (0.59 to 1.10) |

| College or above | 13 254 (30.52) | 34 (0.26) | 0.20 (0.14 to 0.29) | 0.68 (0.43 to 1.05) |

| Household income | ||||

| Low (<US$968/month) | 10 332 (23.79) | 110 (1.06) | Ref | Ref |

| Moderate (US$968–2258/month) | 18 759 (43.20) | 100 (0.53) | 0.46 (0.35 to 0.60) | 0.77 (0.58 to 1.03) |

| High (>US$2258/month) | 14 333 (33.01) | 58 (0.40) | 0.34 (0.25 to 0.46) | 0.68 (0.48 to 0.96) |

| Smoking status | ||||

| Never | 29 685 (68.36) | 132 (0.44) | Ref | Ref |

| Current | 11 074 (25.50) | 107 (0.97) | 2.18 (1.69 to 2.81) | 1.48 (1.08 to 2.03) |

| Ever | 2665 (6.14) | 29 (1.09) | 3.08 (2.06 to 4.61) | 1.33 (0.85 to 2.06) |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| None | 26 833 (61.79) | 150 (0.56) | Ref | Ref |

| Less than once a week | 9196 (21.18) | 27 (0.29) | 0.67 (0.44 to 1.01) | 0.87 (0.57 to 1.33) |

| More than once a week | 7395 (17.03) | 91 (1.23) | 2.18 (1.68 to 2.82) | 1.77 (1.32 to 2.37) |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| Diabetes | 6532 (15.04) | 73 (1.12) | 2.11 (1.61 to 2.76) | 1.05 (0.80 to 1.40) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 1189 (2.74) | 12 (1.01) | 1.79 (1.00 to 3.19) | 0.69 (0.38 to 1.25) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 6421 (14.79) | 110 (1.71) | 4.11 (3.22 to 5.24) | 1.95 (1.47 to 2.60) |

| Asthma | 3689 (8.50) | 50 (1.36) | 2.49 (1.83 to 3.38) | 1.13 (0.81 to 1.57) |

| Cancer | 3004 (6.92) | 44 (1.46) | 2.92 (2.12 to 4.04) | 1.34 (0.95 to 1.87) |

AHR, adjusted HR; Ref, reference.

Figure 2 illustrates the results of the stratified analyses for the association between sex and incident tuberculosis after stratifying the participants by age, smoking and alcohol use. Men had a higher risk of incident tuberculosis than women in all patient subgroups, except those who were current smokers. There were no significant interactions between sex and other variables.

Figure 2.

Stratified analysis for the associations between sex and incident tuberculosis after adjusting for patient characteristics. Reference group: women. Values >1.0 indicate an increased risk. AHR, adjusted HR.

Discussion

This retrospective cohort study revealed that the incidence rates of tuberculosis were 97.6 and 43.2 per 100 000 person-years in men and women, respectively. After adjusting for age, smoking, alcohol use, socioeconomic status and comorbidities, men had a significantly higher risk of active tuberculosis than women. Our study showed robust associations between sex and tuberculosis after stratifying participants by age, smoking and alcohol use. Men had a higher risk of incident tuberculosis than women in all subgroups, except those with current smoking.

This study found that men had a 2.3-fold higher risk of active tuberculosis than women. A previous report showed that male adults in Italy had a twofold higher risk of incident tuberculosis than female adults.15 Moreover, a study in China indicated that the average annual incidence of tuberculosis was 111.75 per 100 000 in men and 43.44 per 100 000 in women.16 Since tuberculosis remains a common disease throughout a majority of the world,17 our study suggests that men should be the target population for tuberculosis prevention.

Sex hormones may explain the higher risk of active tuberculosis in men. Prior reports showed that testosterone could impair macrophage activation and lower the production of proinflammatory cytokines,7 which may increase the susceptibility to tuberculosis infection. However, oestrogens are the inducer of proinflammatory cytokines9 10 and can enhance macrophage activation,18 which could provide protection against tuberculosis infection. In a randomised experimental study, male mice had a lower production of cytokines (eg, tumour necrosis factor-α, interleukin-17) than female mice during the first month of tuberculosis infection.19 Moreover, male mice had a higher burden of Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacilli than female mice during the active tuberculosis disease.19 However, when orchidectomy was performed on male mice with tuberculosis, the burden of M. tuberculosis bacilli significantly decreased.19 The high susceptibility of male mice to tuberculosis infection was prevented by castration19 and may indicate that a male sex hormone is a significantly susceptible factor for tuberculosis infection.

The access to healthcare was different between men and women.20 A previous study reported that barriers to accessing healthcare among women may cause undernotification and a low incidence of tuberculosis.21 However, Taiwan has launched its single-payer NHI programme in 1995.22 More than 99% of the population in Taiwan were enrolled in this NHI programme.23 Therefore, barriers to accessing healthcare among women would be less likely to explain the higher incidence of tuberculosis in men than in women in this report.

This study also found that men had a significantly higher proportion of smoking and alcohol use than women. Previous studies showed that smoking24 and alcohol use25 were the risk factors for active tuberculosis. The high proportion of smoking and alcohol use in men may account for the difference in susceptibility to active tuberculosis between men and women. However, when this study conducted subgroup analysis, after stratifying the subjects by smoking and alcohol use, men were found to have a higher risk of active tuberculosis than women in all subgroups, except those who were current smokers. Overall, the findings in this study indicated that a male sex is an independent risk factor for active tuberculosis.

This study has several strengths. This study used a large national health survey to access a representative cohort and was cross-linked with the NHI database, which has more than a 99% nationwide coverage. The involvement rate was high in the three rounds of NHIS (94% in 2001, 81% in 2005, and 84% in 2009), and so the possibility of selection bias could be excluded.26 The NHIS was planned and accomplished by a well-experienced national survey group using a standard interview process. Detailed personal information was collected during the interview, which allowed us to adjust for the major risk factors for tuberculosis in the analysis.

Even so, two limitations should be warranted. First, the data regarding the bacteriological results for tuberculosis diagnosis were not available in this study. The definition of tuberculosis relied on ICD-9-CM codes and medication prescription history of antituberculosis drugs, and the outcome of incident tuberculosis could have therefore been misclassified. Second, because almost all our subjects were Taiwanese, the external validity of the results should be a concern. Therefore, the generalisability of our results to other ethnic groups around the world requires further verification. Nevertheless, our findings may have vital clinical implications for designing tuberculosis control strategies. Because tuberculosis is still a common infectious disease in the world,17 future tuberculosis control strategies should particularly target the male population.

Conclusions

This retrospective cohort study from Taiwanese population provides confirmation on the association between sex and active tuberculosis. Our study showed that men had a significantly higher risk of active tuberculosis than women, after adjusting for age, socioeconomic status, smoking habit, alcohol use and comorbidities. Since tuberculosis remains a common infectious disease worldwide, our study suggests that future tuberculosis control programmes should particularly target the male population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the members of the research group of Taiwan National Health Interview Survey and National Health Insurance Research Database for their valuable contributions to data collection and management. The authors are also grateful for statistical consultation at the Biostatistical Consultation Centre, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Footnotes

Y-L and DC contributed equally.

Contributors: Y-FY, H-YH, Y-LL, P-WK, PHC, Y-JL and DC had completely dealt with all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis. Y-FY, H-YH, Y-LL, M-CK, P-HC, Y-JL and DC assisted in data interpretation. Y-FY and Y-JL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was supported by the Department of Health, Taipei City Government (TPCH-104-005).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: A committee of the Institutional Review Board of Taipei City Hospital approved this study (TCHIRB-10404118-W).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data analysis was guided by the monitoring regulation guidelines of the Scientific Data Center of the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan. All data are open for accessing following the approved security protocols with specific processes.

References

- 1.Getahun H, Matteelli A, Chaisson RE, et al. . Latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. N Engl J Med 2015;372:2127–35. 10.1056/NEJMra1405427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control 2017. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/ (accessed 29 Nov 2017).

- 3.Taiwan Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Promulgated definitions of TB. Taipei, Taiwan: CDC, 2017. Chinese http://nidss.cdc.gov.tw/singledisease.aspx?pt=s&dc=1&dt=3&disease=010 (accessed 16 Jul 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boissier J, Chlichlia K, Digon Y, et al. . Preliminary study on sex-related inflammatory reactions in mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni. Parasitol Res 2003;91:144–50. 10.1007/s00436-003-0943-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villacres MC, Longmate J, Auge C, et al. . Predominant type 1 CMV-specific memory T-helper response in humans: evidence for gender differences in cytokine secretion. Hum Immunol 2004;65:476–85. 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.02.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fischer J, Jung N, Robinson N, et al. . Sex differences in immune responses to infectious diseases. Infection 2015;43:399–403. 10.1007/s15010-015-0791-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.D’Agostino P, Milano S, Barbera C, et al. . Sex hormones modulate inflammatory mediators produced by macrophages. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;876:426–9. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07667.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rook GA, Hernandez-Pando R, Dheda K, et al. . IL-4 in tuberculosis: implications for vaccine design. Trends Immunol 2004;25:483–8. 10.1016/j.it.2004.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuckerman SH, Bryan-Poole N, Evans GF, et al. . In vivo modulation of murine serum tumour necrosis factor and interleukin-6 levels during endotoxemia by oestrogen agonists and antagonists. Immunology 1995;86:18–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox HS, Bond BL, Parslow TG. Estrogen regulates the IFN-gamma promoter. J Immunol 1991;146:4362–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shih YT HY, Chang HS, Liu JP, et al. . The design, contents, operation and the characteristics of the respondents of the 2001 National Health Interview Survey in Taiwan. Taiwan Journal of Public Health 2003;22:419–30. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ou SM, Liu CJ, Teng CJ, et al. . Impact of pulmonary and extrapulmonary tuberculosis infection in kidney transplantation: a nationwide population-based study in Taiwan. Transpl Infect Dis 2012;14:502–9. 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2012.00737.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Narasimhan P, Wood J, Macintyre CR, et al. . Risk factors for tuberculosis. Pulm Med 2013;2013:1–11. 10.1155/2013/828939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yen YF, Chung MS, Hu HY, et al. . Association of pulmonary tuberculosis and ethambutol with incident depressive disorder: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. J Clin Psychiatry 2015;76:e505–11. 10.4088/JCP.14m09403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stival A, Chiappini E, Montagnani C, et al. . Sexual dimorphism in tuberculosis incidence: children cases compared to adult cases in Tuscany from 1997 to 2011. PLoS One 2014;9:e105277 10.1371/journal.pone.0105277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen M, Kwaku AB, Chen Y, et al. . Gender and regional disparities of tuberculosis in Hunan, China. Int J Equity Health 2014;13:32 10.1186/1475-9276-13-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyons JG, Stewart S. Commentary: tuberculosis, diabetes and smoking: a burden greater than the sum of its parts. Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:230–2. 10.1093/ije/dys217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calippe B, Douin-Echinard V, Laffargue M, et al. . Chronic estradiol administration in vivo promotes the proinflammatory response of macrophages to TLR4 activation: involvement of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase pathway. J Immunol 2008;180:7980–8. 10.4049/jimmunol.180.12.7980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bini EI, Mata Espinosa D, Marquina Castillo B, et al. . The influence of sex steroid hormones in the immunopathology of experimental pulmonary tuberculosis. PLoS One 2014;9:e93831 10.1371/journal.pone.0093831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ojanuga DN, Gilbert C. Women’s access to health care in developing countries. Soc Sci Med 1992;35:613–7. 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90355-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hudelson P. Gender differentials in tuberculosis: the role of socio-economic and cultural factors. Tuber Lung Dis 1996;77:391–400. 10.1016/S0962-8479(96)90110-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng TM. Taiwan’s new national health insurance program: genesis and experience so far. Health Aff 2003;22:61–76. 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu CY, Chen YJ, Ho HJ, et al. . Association between nucleoside analogues and risk of hepatitis B virus–related hepatocellular carcinoma recurrence following liver resection. JAMA 2012;308:1906–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin HH, Ezzati M, Chang HY, et al. . Association between tobacco smoking and active tuberculosis in Taiwan: prospective cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;180:475–80. 10.1164/rccm.200904-0549OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amoakwa K, Martinson NA, Moulton LH, et al. . Risk factors for developing active tuberculosis after the treatment of latent tuberculosis in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Open Forum Infect Dis 2015;2:ofu120 10.1093/ofid/ofu120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taiwan National Health Research Institutes. National health interview survey. Chinese http://nhis.nhri.org.tw/2001download.html (accessed 16 Jul 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.