A fundamental, yet largely unexplored problem is how different cellular processes that act within the same chromatin space communicate with each other. A prime example is the processes of DNA repair and transcription. While for many years it has been appreciated that transcription involves covalent modification and large scale chromatin alterations, it has more recently become clear that DNA double strand break (DSB) repair also leads to considerable chromatin modification. The intersection of these pathways was the focus of our recent study.1

The ubiquitylation of histone H2A (uH2A) is a chromatin mark present both at DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) and at transcriptionally silenced regions of the genome. Based on this commonality, we asked whether uH2A could provide a link between the seemingly disparate chromatin- mediated processes of DNA damage and transcription. To address this question, we imparted a previously described transcriptional reporter2 with the ability to introduce DSBs several kilobases upstream from an inducible transgene. The nuclease domain of the FokI endonuclease was fused to the lac repressor (LacI), targeting nucleolytic activity through binding of the LacI protein to lac operator elements in the reporter. Importantly, this approach leads to persistent damage, allowing a study of early and possibly transient events at DSBs. Such events may be missed in assays that utilize site-specific nucleases, due to rapid target site loss following imperfect repair.

Using this system and complementary approaches, we discovered an ATM-dependent transcriptional silencing program that spreads kilobases from sites of DSBs. Silencing was also detected at endogenous genes using nuclear run-on techniques following ionizing radiation induced DSBs, further demonstrating that nascent transcription is largely absent in chromatin containing DSBs. We have named the phenomenon Double Strand Break-Induced Silencing in Cis (DISC).

How does ATM activity transmit a signal through large stretches of chromatin to silence transcription distal to DSBs? Silencing relies in part on uH2A, while the resumption of transcription after ATM inhibition or repair of the break depends on uH2A deubiquitylation. Interestingly, efficient knockdown of the E3 ubiquitin ligases thought to be important for the formation of this ubiquitin signal—RNF8 and RNF168—led to a significant but quite modest rescue of transcriptional activity compared to ATM inhibition. This suggests that these two ligases, as well as uH2A itself, may only be part of the silencing mechanism and that additional mechanistic details await discovery.

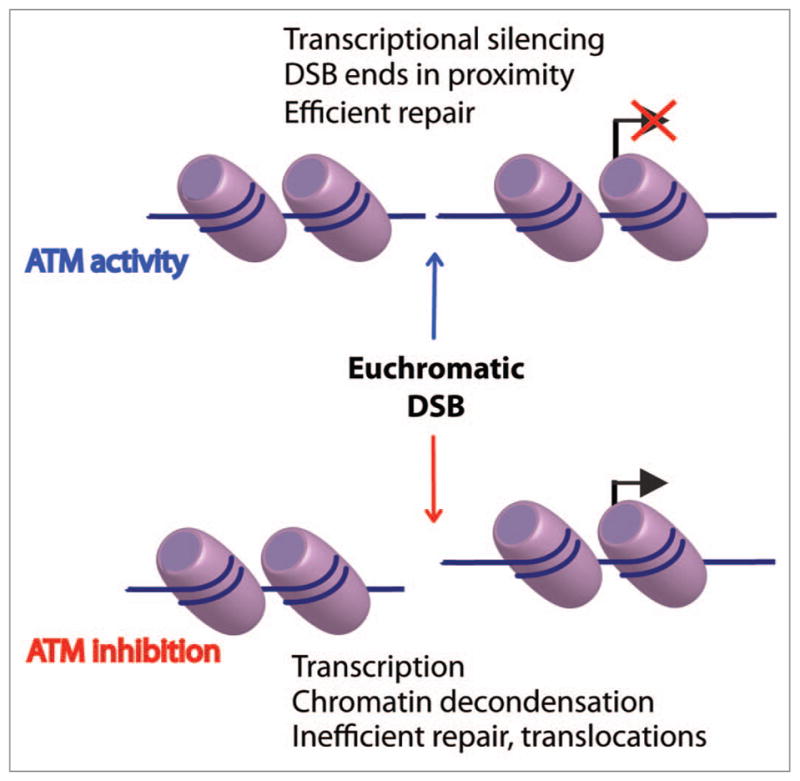

A second question pertains to the biological need for DISC. One possibility stems from the observation that DSB-initiated ATM activity prevents large-scale, transcription-associated chromatin decondensation.1 We hypothesize that such decondensation may physically pull broken DNA ends apart, leading to inefficient repair that predisposes to non-reciprocal translocations (Fig. 1). Several elegant studies point to a role for ATM in relaxing chromatin structure globally, and perhaps even decondensing heterochromatic regions after damage.3,4 Our data suggest an additional role for the kinase in preventing deleterious decondensation in euchromatic regions. A prediction from this model is that ATM inhibition should interfere with DSB repair, specifically in the presence of active transcription. In support of this idea, aberrant transcriptional activity has been correlated with chromosomal translocations in several studies.5,6 Interestingly, in one of these studies, the frequency of transcription dependent translocations was dramatically increased by ATM deficiency.6

Figure 1.

Model of proposed AT M activity at euchromatic DNA double strand breaks (DSBs). Top: AT M kinase activity silences transcription on stretches of euchromatin contiguous to DSBs, ensuring proximity of DSB termini and efficient repair. Bottom: in the absence of AT M activity, transcription and associated chromatin decondensation occur in the vicinity of euchromatic DSBs, increasing the distance between DSB termini and potentially reducing repair efficiency and predisposing to chromosomal translocations.

Another area of interest is the potential contribution of DSB silencing to cancer-associated epigenetic alterations. It is important to note that DISC was completely reversible with kinetics that closely paralleled DSB repair, suggesting that DSBs do not typically enact permanent changes to chromatin. Nonetheless, several interesting studies have documented heritable silencing at a subset of repaired nuclease-induced breaks.7,8 This raises the possibility that failure to reverse DSB-associated chromatin changes could lead to stable and heritable chromatin changes in a biologically significant manner, particularly in the case of clonal diseases such as cancer. It will be of interest to determine whether persistent DISC contributes to tumor-associated epigenetic changes and silencing of tumor suppressor genes.

Finally, it is possible DSB-induced silencing may represent a cellular defense mechanism against foreign genomes. The herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is maintained in a latent, circular, episomal state that is predominately transcriptionally silent. Various stresses, including DNA damage, however, can reactivate the viral genome into a transcriptionally active and replicating state that is linear and thus potentially recognized as a DSB. The HSV-1 protein ICP0, an E3 ubiquitin ligase known to have many targets including several members of the DNA damage response, was recently shown to degrade the ubiquitin ligases RNF8 and RNF168.9 As these ligases are at least in part responsible for silencing at DSBs, it is possible that the viral protein would also rescue transcription at breaks. Though ICP0 could prove to be a potent tool to study this phenomenon, it also suggests DISC mechanisms may prevent uncontrolled transcription of foreign genomes resembling DSBs, and that pathogens have evolved to combat these cellular defenses.

References

- 1.Shanbhag NM, et al. Cell. 2010;141:970–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.04.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janicki SM, et al. Cell. 2004;116:683–98. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00171-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ziv Y, et al. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:870–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goodarzi AA, et al. Mol Cell. 2008;31:167–77. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mathas S, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:5831–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900912106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin C, et al. Cell. 2009;139:1069–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.O’Hagan HM, et al. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cuozzo C, et al. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:110. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lilley CE, et al. EMBO J. 2010;29:943–55. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]