Abstract

Müller glial (MG) cells in the zebrafish retina respond to injury by acquiring retinal stem-cell characteristics. Thousands of gene expression changes are associated with this event. Key among these changes is the induction of Ascl1a and Lin28a, two reprogramming factors whose expression is necessary for retina regeneration. Whether these factors are sufficient to drive MG proliferation and subsequent neuronal-fate specification remains unknown. To test this, we conditionally expressed Ascl1a and Lin28a in the uninjured retina of male and female fish. We found that together, their forced expression only stimulates sparse MG proliferation. However, in combination with Notch signaling inhibition, widespread MG proliferation and neuron regeneration ensued. Remarkably, Ascl1 and Lin28a expression in the retina of male and female mice also stimulated sparse MG proliferation, although this was not enhanced when combined with inhibitors of Notch signaling. Lineage tracing in both fish and mice suggested that the proliferating MG generated multipotent progenitors; however, this process was much more efficient in fish than mice. Overall, our studies suggest that the overexpression of Ascl1a and Lin28a in zebrafish, in combination with inhibition of Notch signaling, can phenocopy the effects of retinal injury in Müller glia. Interestingly, Ascl1 and Lin28a seem to have similar effects in fish and mice, whereas Notch signaling may differ. Understanding the different consequences of Notch signaling inhibition in fish and mice, may suggest additional strategies for enhancing retina regeneration in mammals.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Mechanisms underlying retina regeneration in fish may suggest strategies for stimulating this process in mammals. Here we report that forced expression of Ascl1 and Lin28a can stimulate sparse MG proliferation in fish and mice; however, only in fish does Notch signaling inhibition collaborate with Ascl1a and Lin28a to stimulate widespread MG proliferation in the uninjured retina. Discerning differences in Notch signaling between fish and mice MG may reveal strategies for stimulating retina regeneration in mammals.

Keywords: Ascl1, Lin28, Müller glia, Notch, regeneration, retina

Introduction

Blinding eye diseases, like glaucoma and macular degeneration result from the death of retinal ganglion cells and photoreceptors. Neural regeneration has the potential to restore sight to the blind by generating replacements for these lost cells. Teleost fish, like zebrafish, exhibit a robust regenerative response to retinal injury that results in neuron regeneration and restoration of visual function (Lindsey and Powers, 2007; Sherpa et al., 2008; Wan and Goldman, 2016). Unfortunately, mammals have lost the ability to regenerate any retinal cells once they have been lost. Understanding the pathways by which zebrafish regenerate neurons in response to injury may suggest therapeutic strategies for initiating retinal cell regeneration in mammals.

In zebrafish, retina regeneration is initiated in Müller glia (MG) that respond to retinal injury by undergoing a reprogramming event that endows them with stem-cell characteristics and allows them to divide and generate multipotent progenitors for retinal repair (Goldman, 2014; Wan and Goldman, 2016). Many signaling cascades and gene expression programs underlying MG reprogramming and retina regeneration have been identified (Ramachandran et al., 2010b, 2011, 2012; Thummel et al., 2010; Nelson et al., 2012, 2013; Conner et al., 2014; Rajaram et al., 2014; Wan et al., 2012, 2014; Zhao et al., 2014). In particular, Ascl1a and Lin28a have emerged as major regulators of the regenerative program (Fausett et al., 2008; Ramachandran et al., 2010b, 2011; Nelson et al., 2012). Ascl1a is a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor and Lin28 is an RNA binding protein. Following retinal injury in zebrafish, there is a rapid and dramatic increase in ascl1a and lin28a gene expression that precedes MG proliferation. Knockdown of Ascl1a or Lin28a reduces the injury-dependent activation of many regeneration-associated genes and this results in a reduced proliferative response by MG (Fausett et al., 2008; Ramachandran et al., 2010b, 2011; Nelson et al., 2012).

Interestingly, these two proteins also participate in somatic cell reprogramming in mammals. Ascl1 can reprogram fibroblasts to adopt neuronal characteristics and Lin28 participates in reprogramming fibroblasts to pluripotency (Yu et al., 2007; Chanda et al., 2014). Furthermore, forced expression of Ascl1 or Lin28 can stimulate some MG proliferation in the injured and uninjured mouse retina, respectively; however, most of these cells do not survive (Ueki et al., 2015; Yao et al., 2016). Although Ascl1a and Lin28a are necessary for MG proliferation and retina regeneration in zebrafish, it is not known whether they are sufficient to drive these processes in the uninjured fish retina.

We hypothesized that proteins that are sufficient to drive MG proliferation and retina regeneration in fish will be the most potent in stimulating these processes in mammals. Therefore, we searched for gene combinations that would stimulate MG proliferation in the uninjured zebrafish retina. We found that coexpression of Ascl1a and Lin28a stimulated a small amount of MG proliferation in the uninjured retina. Furthermore, in the injured retina, this expression expanded the zone of injury-responsive MG. Interestingly, the inhibition of Notch signaling dramatically enhanced the effects of Ascl1a and Lin28a on MG proliferation, resulting in widespread proliferation throughout the uninjured fish retina. Finally, Ascl1 and Lin28a coexpression stimulated a small amount of MG proliferation in the uninjured mouse retina, which was increased with retinal injury. However, unlike in fish, Notch inhibition had little effect on this proliferation.

Materials and Methods

Animals.

Animal studies were approved by the University of Michigan's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Zebrafish were kept at 26–28°C with a 10/14 h light/dark cycle. Adult male and female fish from 6 to 12 months of age were used in these studies. 1016 tuba1a:GFP, gfap:GFP, and tp1:mCherry fish were previously described (Fausett and Goldman, 2006; Kassen et al., 2007; Parsons et al., 2009; Kwon et al., 2010). We generated 1016 tuba1a:GFP;hsp70:flag-myc-ascl1a (referred to as hsp70:ascl1a) and 1016 tuba1a:GFP;hsp70:myc-lin28a (referred to as hsp70:lin28a) transgenic fish. The 1016 tuba1a:GFP expression cassette was used to identify fish harboring the various ascl1a and lin28a transgenes and the flag and myc tags were used to ensure protein expression after heat shock. The hsp70:ascl1a and hsp70:lin28a transgenic lines were created using standard recombinant DNA techniques using Tol2 vector backbone. Expression constructs were injected into single-cell zebrafish embryos as previously described (Fausett and Goldman, 2006). Retinas were injured with a needle poke injury as previously described (Fausett and Goldman, 2006; Montgomery et al., 2010; Powell et al., 2016). Wild-type C57BL/6J mice were obtained from our breeding colony. DNMAML mice harbor amino acids 13–74 of MAML1 fused to GFP (Maillard et al., 2006).

AAV, intravitreal injection, retinal injury, and BrdU/EdU labeling.

A Müller cell-specific AAV capsid variant, ShH10 was used to deliver genes to MG (Klimczak et al., 2009). GFP, mouse Ascl1, human Lin28a, and Cre expression cassettes, under control of the CAG, CMV, or TetCMV promoters were individually packaged into ShH10 AAV vectors. Recombinant ShH10 AAV was prepared as previously described (Klimczak et al., 2009; Flannery and Visel, 2013). Viral titers were between ∼0.5 × 1013 to 5 × 1013 vg/ml and ∼1 μl was intravitreally injected into isoflurane anesthetized postnatal day (P)17 mice using a Hamilton syringe equipped with a 33-gauge needle. Adult (P41) mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and received ∼2 μl intravitreal injections of PBS containing 1 mg/ml BrdU or EdU, ±100 mm NMDA using a Hamilton syringe equipped with a 33-gauge needle. Mice received a second intravitreal injection of BrdU/EdU 3 d later; mice also received daily intraperitoneal injections of BrdU/EdU (50 μg/g body weight) for 3 d following NMDA treatment.

Fish were anesthetized in tricaine and retinas were injured with a needle poke injury as previously described (Fausett and Goldman, 2006). Fish received an intraperitoneal injection of BrdU (20 μl of 20 mm stock) at 4 d postinjury (dpi). For growth factor treatment, fish were anesthetized with tricaine and the left eye (control) was intravitreally injected with ∼1 μl of vehicle (PBS, 0.1% BSA) and the right eye was injected with ∼1 μl of HB-EGF (50 ng/μl; R&D Systems) or insulin (500 ng/μl; Invitrogen), pH7.6, using a Hamilton syringe equipped with a 33-gauge needle as previously described (Wan et al., 2014). Recombinant proteins were injected once daily for 3 d, and 4 d after the first injection fish received an intraperitoneal injection of BrdU (20 μl of 20 mm stock).

RNA isolation and PCR.

Total RNA was isolated using Trizol (Invitrogen). cDNA synthesis and PCRs were performed as previously described (Fausett et al., 2008; Ramachandran et al., 2010b). Real-time qPCRs were performed in triplicate with ABsolute SYBR Green Fluorescein Master Mix (Thermo Scientific) on an iCycler real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad). The ΔΔCt method was used to determine relative expression of mRNAs in control and injured retinas and normalized to gapdh or γ-actin mRNA levels. To assay let7g miRNA, poly(A) tails were first added to total RNA (Ambion) and then samples were reverse transcribed with Superscript II and a poly(T) adapter. Following cDNA synthesis real-time qPCR was performed as described above. Individual comparisons were done using unpaired two-tailed Student's t test. ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD post hoc analysis was used for multiple-parameter comparison. Error bars are SD.

Western blots.

Samples were boiled in SDS sample loading buffer and fractionated on 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. Samples were then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk, and incubated in primary antibodies mouse anti-myc (1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich, catalog #M4439) or mouse anti-flag (1:2000; Sigma-Aldrich, catalog #F1804) at 4°C overnight. Membranes were then washed in 0.1% Triton-X in PBS three times and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody goat anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000; Rockland, catalog #610-1302) in 5% nonfat dry milk for 2 h at room temperature and visualized using an ECL kit (ThermoFisher). Western blots were quantified using NIH ImageJ software.

Primers used in this study.

The following primers are 5′ to 3′. Unless otherwise indicated primers are for zebrafish. ascl1a–Forward: ATTCCAGTCGGGCGTCCTGTCA, Reverse: CCTCCCAAGCGAGTGCTGATATTTT; cdk1–Forward: GCTTCACGCTATTCCACACC, Reverse: GCCAGATTCCCAGATTTCCAC; cdk2–Forward: GACTACAAACCCTCCTTTCCC, Reverse: AAACCGATGAACAAGAGCGT; cdk4–Forward: GCAGTATGAGCCAGTAGCAG, Reverse: ATGTTGGGATGGTCGAACTG; ccna2–Forward: ACGAGACTCTTTACCTGGCT, Reverse: GAGAGAACTGTCAGCACCAG; ccnb1–Forward: TGACATGGTCCACTACCCTC, Reverse: GATGCTTAGAAAGGCCCTCG; ccnd–Forward: AAGTGGGATCTGGCCTCAGT, Reverse: GGCAACTGTCGGTGCTTTTC; dkk1b–Forward: AAGCACAAGAGGAAAGGCA, Reverse: TGGGAGCTGGTGAAAGAAA; gapdh–Forward: ATGACCCCTCCAGCATGA, Reverse: GGCGGTGTAGGCATGAAC;; insm1a–Forward: GCACCACAGTAACCACCAAA, Reverse: TGCACAGCTGACAGACGAAC; lepb–Forward: TCCCCGTCACCTCCAACTAC, Reverse: TCCTTGCATGTGCCATTGTGT; lin28a–Forward: TAACGTGCGGATGGGCTTCGGATTTCTGTC, Reverse: ATTGGGTCCTCCACAGTTGAAGCATCGATC; mcm5–Forward: CCAGTAGGAGAAGAGACTGT, Reverse: TCTGCATCCGCGGCACTGAA; mych–Forward: CCCGACCGCTTAAAACTGGA, Reverse: CTCATCGTCAAACAGCAACGG; mycn–Forward: CAGAACAGTCTTCAGTCGCC, Reverse: ATCCTCGTCCGGGTAGAAAC; socs3a–Forward: CACTAACTTCTCTAAAGCAGGG, Reverse: GGTCTTGAAGTGGTAAAACG; stat3–Forward: AGCAGCAAAGAGGGAGGAATCACA, Reverse: GTACAGGTAGACCAGCGGCGACAC; her4.1–Forward: GCTGATATCCTGGAGATGACG, Reverse: GACTGTGGGCTGGAGTGTGTT; Mouse-Gapdh–Forward: TCAACAGCAACTCCCACTCTTCCACCTTC, Reverse: ACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCGTATTCA; Mouse γ-ctin–Forward: AGAAGAAATCGCCGCACTCGTCAT, Reverse: CCTCTTGCTCTGGGCCTCGTCAC; Mouse Ascl1a–Forward: TCTCGTCCTACTCCTCCGAC, Reverse: ATTTGACGTCGTTGGCGAGA; Mouse-Lin28a–Forward: CCTTTGCCTCCGGACTTCTC, Reverse: AGGGCTGTGGATCTCTTCCT; Mouse-Let7 g–Forward: TGAGGTAGTAGTTTGTACAGTT, Reverse: GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGG(T)12VN; Mouse-Hes5–Forward: TAATCGCCTCCAGAGCTCCA, Reverse: GCGAAGGCTTTGCTGTGTTT; Mouse-Hes1–Forward: ACACCGGACAAACCAAAGAC, Reverse: ATGCCGGGAGCTATCTTTCT; Mouse-Hey1–Forward: TGAGCTGAGAAGGCTGGTAC, Reverse: ACCCCAAACTCCGATAGTC.

Heat shock, Notch inhibition, and TUNEL.

For heat shock, fish were immersed in a water bath at 37°C for 1 h before returning to system water at 28°C. For extended periods of heat shock, this was repeated every 6 h. To inhibit Notch signaling in fish, we immersed fish in water containing 40 μm DAPT (Sigma-Aldrich) or RO4929097 (Cayman) prepared in DMSO and diluted 1/200 in fish water. Control fish were immersed in fish water treated with DMSO (1:200). To inhibit Notch signaling in mice, we intravitreally injected DAPT (100 μm) daily into the eye of Wt mice for up to 4 d, or we injected shH10 AAV Cre into the eye's vitreous of DNMAML-GFP mice 1–2 weeks before NMDA injury and/or analysis.

We used an in situ Cell Death Detection Kit (TMR red; Applied Science) to detect cells undergoing apoptosis.

Immunohistochemistry, in situ hybridization, and microscopy.

Zebrafish samples were prepared for immunofluorescence as previously described (Fausett and Goldman, 2006; Ramachandran et al., 2010a,b). Preparation of mouse samples was similar to fish except retinas were fixed for 20–30 min in 2% paraformaldehyde. Primary antibodies used in this study: Zpr-1, Zebrafish International Resource Center (1/500); anti-HuC/D, Invitrogen, catalog #A-21275 (1/500); anti-PKCβ1, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, catalog #SC-209 (1/200); anti-glutamine synthetase (GS), EMD Millipore, catalog #MAB302 (1/500); anti-BrdU, ThermoFisher, catalog #MA 1-82088 (1/500); anti-CRX, Abnova, catalog #H00001406-M02 (1/1000); anti-SOX9, EMD Millipore, catalog #AB5535 (1/500); anti-Chx10 antibody, EMD Millipore, catalog #AB-9016 (1/300); anti-RBPMS, Phospho Solutions, catalog #1830-RBPMS (1/500); anti-AP2α, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, catalog #3B5 (1/1000); anti-4C4 (Gift from Peter Hitchcock, University of Michigan). Secondary antibodies: AlexaFluor 555 donkey anti-mouse-IgG (H+L), ThermoFisher, catalog #A31570 (1:500); AlexaFluor 555 donkey anti-rabbit IgG (H+L), ThermoFisher, catalog #A31572 (1:500); AlexaFluor 555 donkey anti-sheep IgG (H+L) ThermoFisher, catalog #A21436; Cy3, Jackson ImmunoResearch, catalog #712-166-150 (1:500); AlexaFluor 488 donkey anti-mouse ThermoFisher, catalog #A21202 (1:500); AlexaFluor 488 goat anti-rabbit, ThermoFisher, catalog #A11008 (1:500); Cy5 goat anti-mouse, ThermoFisher, catalog #A10524 (1:500); and AlexaFluor 647 goat anti-rabbit, ThermoFisher, catalog #A21244 (1:500). In situ hybridization was performed as described previously (Barthel and Raymond, 2000). Images were captured by a Zeiss Axiophot fluorescence microscope or an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 confocal microscope.

Cell quantification and statistical analysis.

BrdU immunofluorescence was used to identify and quantify proliferating cells in retinal sections as previously described (Fausett and Goldman, 2006; Ramachandran et al., 2010a; Wan et al., 2012, 2014). All experiments were done in triplicate with three animals per trial. Error bars are SD. ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD post hoc analysis was used for multiple-parameter comparison; two-tailed Student's t test was used for single-parameter comparison.

Results

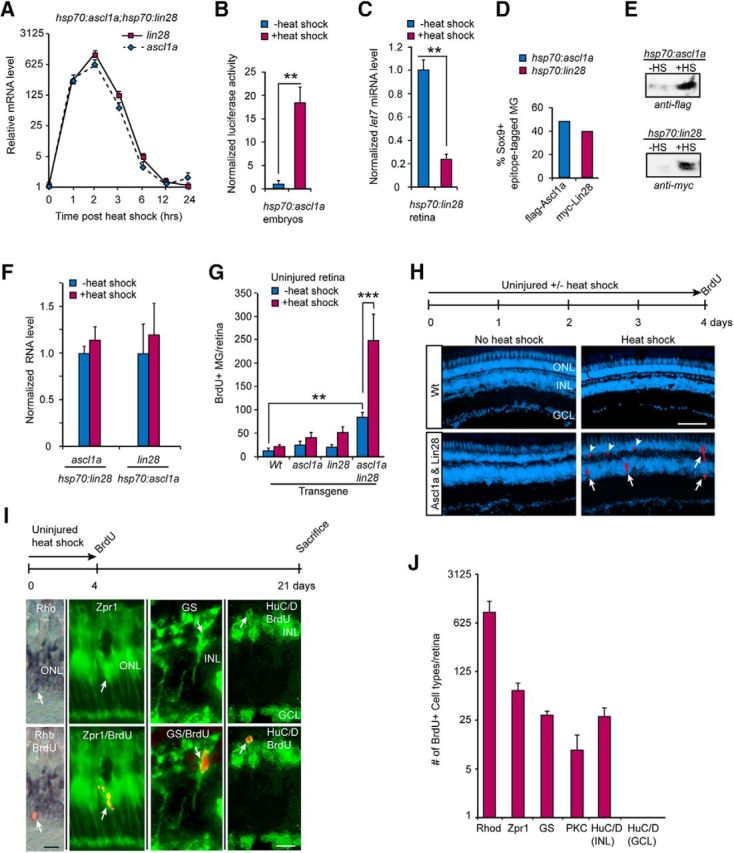

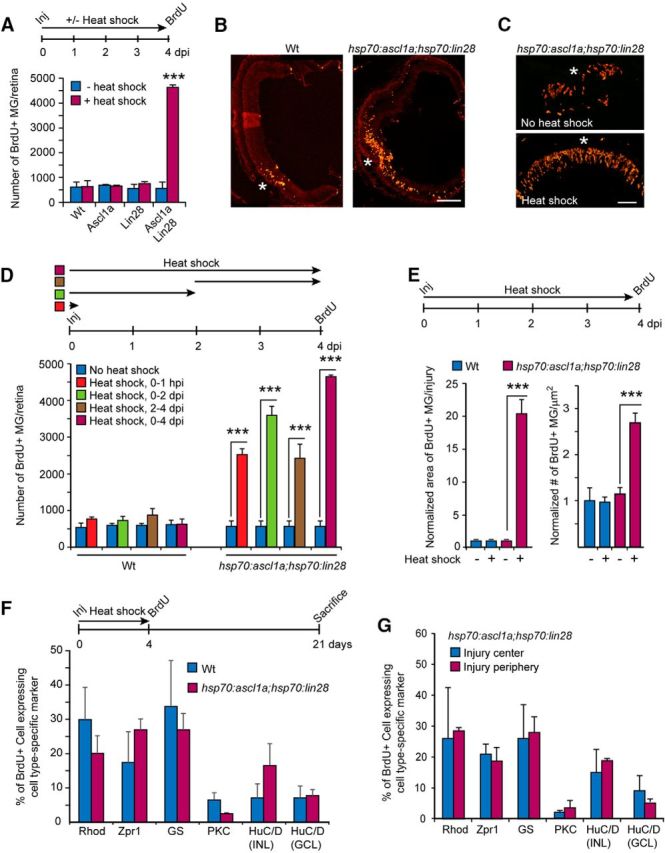

Ascl1a and Lin28a stimulate MG proliferation in the uninjured zebrafish retina

Injury-dependent induction of Ascl1a and Lin28a in zebrafish retinal MG cells allows for their reprogramming and proliferation (Fausett et al., 2008; Ramachandran et al., 2010a). To investigate whether their induction is sufficient to drive MG proliferation in the uninjured retina we generated hsp70:ascl1a and hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish, and also bred these fish to each other to generate hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a double-transgenic fish. These fish allow for conditional Ascl1a and Lin28a expression with heat shock. In these fish, a 1 h heat shock at 37°C stimulates ascl1a and lin28a expression with RNA levels peaking ∼2 h post-heat shock and then returning to basal levels ∼10 h later (Fig. 1A). To maintain transgene expression for more prolonged periods of time, transgenic fish received a 1 h heat shock at 37°C, every 6 h for 1–4 d.

Figure 1.

Forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a stimulates MG proliferation and neuron regeneration in the uninjured retina. A, Time course of ascl1a and lin28a RNA expression in retinas of hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish that received a 1 h heat shock; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. B, Luciferase assays show heat shock of hsp70:ascl1a embryos injected with 4RTK-Luc plasmid results in increased expression of the 4RTK-Luc reporter indicating expression of a functional Ascl1a protein; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. **p < 0.009. C, Heat shock-dependent induction of Lin28a in hsp70:lin28a adult fish results in reduced let7g miRNA expression indicating expression of a functional Lin28a protein; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. **p < 0.01. D, Immunofluorescence quantification of the percentage of Sox9+ MG-expressing flag-Ascl1a and myc-Lin28a 8 h after a 1 h heat shock in hsp70:ascl1a and hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish. E, Western blot analysis showing flag-Ascl1a and myc-Lin28a protein induction 8 h after a 1 h heat shock in hsp70:ascl1a and hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish. F, Forced expression of Lin28a in hsp70:lin28a does not stimulate ascl1a expression and forced expression of Ascl1a in hsp70:ascl1a fish does not induce lin28a RNA expression. G, BrdU immunofluorescence on retinal sections was used to quantify proliferating MG in the INL of uninjured retinas from transgenic fish expressing the indicated transgenes for 4 d; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. H, Timeline of experiment and representative retinal sections showing BrdU immunofluorescence (red) before and after heat shock in Wt and hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish. DAPI nuclear stained cells are blue. Scale bar, 100 μm. I, Timeline of lineage trace experiment and representative retinal sections showing colocalization of either rod rhodopsin (Rho) photoreceptor in situ hybridization signal (left, blue), cone (Zpr1), MG (GS), or amacrine cell (HuC/D in INL) immunofluorescence signal (green), with BrdU immunofluorescence signal (red). Scale bar, 20 μm. J, Quantification of data presented in I; bipolar cells (protein kinase C, PKC); n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD.

We confirmed that hsp70:ascl1a transgenic fish produced a functional protein by injecting embryos with the 4RTK-Luc reporter that harbors four E-box sites (4R) from the MCK enhancer cloned upstream of the thymidine kinase (TK) basal promoter driving firefly luciferase expression (Weintraub et al., 1990). Ascl1 is a helix-loop-helix transcription factor that activates genes via their E-box sequences and thus regulates 4RTK-Luciferase expression. Heat shock of hsp70:ascl1a embryos injected with the 4RTK-Luc reporter stimulated Luciferase expression by >15-fold (Fig. 1B). To test for functional expression of Lin28a in hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish we assayed the effects of heat shock on endogenous let7 miRNA expression in the adult retina. Lin28a inhibits let7 family miRNA maturation and stimulates their degradation (Rybak et al., 2008; Heo et al., 2009). We found that heat shock reduced let7g RNA levels in whole retina by ∼70% (Fig. 1C). Quantification of Sox9 and flag-Ascl1 or myc-Lin28a co-immunofluorescence suggested that a 1 h heat-shock treatment was sufficient to stimulate transgenic protein expression in ∼ 40–50% of the Sox9+ MG when assayed 8 h post-heat shock (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, Western blot analysis revealed ∼40–50-fold induction of flag-tagged Ascl1a (∼30 kDa) and myc-tagged Lin28a (∼29 kDa) protein expression after heat shock (Fig. 1E). Finally, we investigated whether Ascl1a or Lin28a were sufficient to stimulate each other's expression in the uninjured fish retina. For this analysis, hsp70:ascl1a and hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish received heat shock and 24 h later retinas were dissected and assayed for lin28a and ascl1a, respectively. We found no significant effect of forced expression of Ascl1a on lin28a expression, nor did forced Lin28a expression affect ascl1a RNA (Fig. 1F).

To investigate the effects of Ascl1a and Lin28a on MG cell proliferation in the adult retina, fish received an intraperitoneal injection of BrdU 3 h before kill. BrdU immunofluorescence on retinal sections was used to visualize and quantify proliferating MG in the inner nuclear layer (INL) as previously described (Fausett and Goldman, 2006). This analysis showed that neither Ascl1a or Lin28a on their own were able to stimulate MG proliferation (Fig. 1G); however, when expressed together, a significant increase in MG proliferation was observed (Fig. 1G,H). We also observed an increased basal level of MG proliferation in uninjured hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a double-transgenic fish that may reflect a low level of leaky ascl1a and lin28a gene expression in the absence of heat shock (Fig. 1E,G). Finally, a variable, but small number of proliferating cells at the base of the outer nuclear layer (ONL) was detected that probably represent proliferating rod progenitors (Fig. 1H, arrowheads).

In the injured fish retina, MG divide and generate multipotent progenitors that regenerate all major retinal cell types regardless of which cell type is ablated (Powell et al., 2016). However, in the uninjured retina MG rarely proliferate and when they do they appear to be restricted to a rod progenitor lineage (Bernardos et al., 2007). Therefore, we investigated whether forced Ascl1 and Lin28a expression stimulated MG in the uninjured retina to generate multipotent or unipotent progenitors. For this analysis we used a BrdU-based lineage tracing strategy where uninjured hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a fish received heat shock every 6 h for 4 d and then an intraperitoneal injection of BrdU. Fish were then allowed to survive 21 d before harvesting retinas and assaying progenitor fate. Regenerated rods were identified by colocalizing BrdU immunofluorescence with rhodopsin in situ hybridization, whereas other cell types were detected by colocalizing BrdU immunofluorescence with cell-type-specific immunofluorescence. This analysis showed that Ascl1a and Lin28a expression forced some MG to enter the cell cycle and generate a variety of neurons (Fig. 1I,J); however, retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) were not detected. We suspect this reflects the very low number of progenitors that were generated and the relatively small numbers of RGCs normally regenerated from these progenitors (Wan et al., 2012, 2014). The relatively large number of BrdU+ rods after forced Ascl1a and Lin28a expression probably results from proliferating MG-derived multipotent progenitors in the INL (Fig. 1H, arrows) and rod progenitors normally residing at the base of the ONL (Fig. 1H, arrowheads). The above data suggest that in the uninjured retina, Ascl1a and Lin28a expression are sufficient to stimulate some MG to proliferate and generate multipotent progenitors.

Ascl1a and Lin28a act in a synergistic fashion to stimulate MG proliferation in the injured fish retina

Although the above studies suggested that forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a could stimulate MG proliferation in the uninjured retina, the number of proliferating MG was quite modest. We next investigated whether Ascl1a and Lin28a may collaborate with other injury-derived factors to stimulate MG proliferation. For this analysis we injured retinas in Wt, hsp70:ascl1a, hsp70:lin28a, and hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish with a single needle poke. Fish either remained at 28°C or received a 1 h heat shock at 37°C, every 6 h for 4 d. On 4 dpi fish received an intraperitoneal injection of BrdU 3 h before kill. Retinas were then isolated and sectioned, and proliferating MG identified by BrdU immunofluorescence. This analysis revealed that forced expression of either Ascl1a or Lin28a had little effect on injury-dependent MG proliferation (Fig. 2A). However, forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a together, dramatically enhanced MG proliferation at the injury site and expanded the zone of injury-responsive (BrdU+) MG flanking the injury site (Fig. 2A–C).

Figure 2.

Forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a in the injured retina stimulates MG proliferation and retina regeneration. A, Timeline for experiment and graph showing quantification of BrdU immunofluorescence in INL of injured retinas (needle poke) with forced expression of Ascl1a, Lin28a, or Ascl1a and Lin28a; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. ***p < 0.001. B, C, Representative images of retinal sections showing BrdU immunofluorescence at the site of injury (needle poke) in Wt and hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish with heat shock. Scale bars: B, 150 μm; C, 50 μm. D, Timeline depicting retinal needle poke injury (Inj) followed by a 0–1 hpi, 0–2 dpi, 2–4 dpi, and 0–4 dpi heat shock-treatment and BrdU labeling at 4 dpi. Graph shows quantification of BrdU immunofluorescence in the retina's INL of Wt and hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. ***p < 0.001. E, Timeline of experiment, and graph quantifying the retinal area occupied by BrdU+ MG and their density in Wt and hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish ± heat shock. For this analysis a single needle poke injury was made in each retina. Four days later we quantified the area occupied by proliferating MG by counting the number of 12 μm sections spanning the injury site that harbor nine or more BrdU+ MG. Their density per square micrometer was calculated from the three central section's spanning the injury site. Data are normalized to Wt, no heat shock. Error bars are SD. ***p < 0.001; n = 3 different experiments. F, BrdU lineage trace experiment shows forced Ascl1a and Lin28a expression in the injured retina does not bias progenitors toward specific fates. Shown is timeline of experiment and graph quantifying the percentage of BrdU+ cells expressing a particular retinal cell-type marker. Markers are as follows: rods (rho), cones (zpr1), MG (GS), Bipolar (protein kinase C-β1, PKC), amacrine (HuC/D in INL), and ganglion cells (HuC/D in GCL); n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. G, BrdU lineage trace experiment performed as in F shows MG-derived progenitors in the central and peripheral regions of the injury site do not exhibit biases in regenerated cell types when forced to express Ascl1a and Lin28a; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD.

Quantification of the proliferative response in Wt and hsp70ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a fish with heat shock from 0 to 1 h postinjury (hpi), 0–2 dpi, 2–4 dpi, or 0–4 dpi, revealed that as little as 1 h of heat shock-dependent induction of Ascl1a and Lin28a was sufficient to stimulate MG proliferation (Fig. 2D). Quantification of the area occupied by BrdU+ MG and the density of BrdU+ MG near the injury site indicated that the forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a, expanded the zone of injury-responsive MG (BrdU+) and increased the density of BrdU+ MG within this zone (Fig. 2E). Thus, Ascl1a and Lin28a seem to act very early during the injury response to affect MG reprogramming and proliferation.

We next investigated whether forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a in the injured retina influenced the fate of MG-derived progenitors. For this analysis we used a BrdU-based lineage tracing strategy where Wt and hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a fish retinas were injured with a needle poke and then received heat shock every 6 h for 4 d before receiving an intraperitoneal injection of BrdU. Fish were then allowed to survive to 21 dpi before harvesting retinas and assaying progenitor fate in retinal sections using BrdU and retinal cell-type-specific immunofluorescence. This analysis showed that forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a did not impose a significant bias on progenitor fate (Fig. 2F). This global analysis of progenitor fate may have minimized differences occurring in the peripheral regions flanking the injury site where normally quiescent MG are recruited to an injury response by Ascl1a and Lin28a overexpression. However, when the fate of progenitors close to the injury site was compared with those at the periphery of the injury-responsive region no significant difference was noted (Fig. 2G). Thus, together these data suggest that MG-derived progenitors resulting from forced Ascl1a and Lin28a expression in both the uninjured and injured retina are intrinsically multipotent.

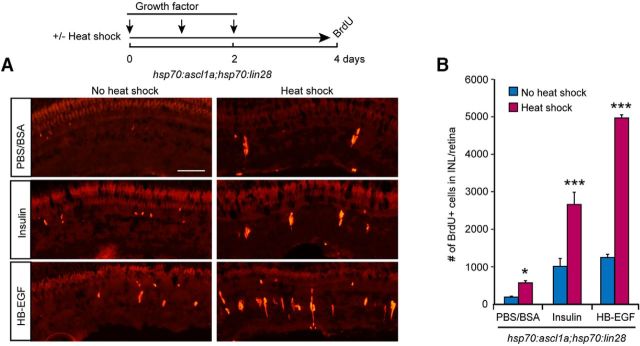

Ascl1a and Lin28a enhance MG responsiveness to injury-related growth factors

The above data showed that forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a recruits normally quiescent MG that flank the injury site to mount a proliferative response. This could result from a lowering of the threshold at which MG respond to injury-derived factors. We previously reported that growth factors, like HB-EGF and insulin, are increased at the injury site and capable of stimulating MG proliferation (Wan et al., 2012, 2014). To investigate whether forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a lowered the threshold at which MG proliferate upon challenge with growth factors, we divided uninjured hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish into two groups; one group received heat shock, whereas the other did not. Both groups received 3 daily intravitreal injections of PBS-BSA, insulin, or HB-EGF at concentrations that caused only a small amount of MG proliferation; 2 d later, fish received an intraperitoneal injection of BrdU 3 h before kill (Fig. 3A). BrdU immunofluorescence on retinal sections was used to visualize and quantify MG proliferation in the INL. This analysis showed a significant increase in MG proliferation in fish with forced Ascl1a and Lin28a expression (Fig. 3A,B), which is consistent with the idea that Ascl1a and Lin28a lowers the threshold at which MG mount a proliferative response to injury-induced growth factor expression. Furthermore, this reduced threshold can explain why the zone of proliferating MG is expanded in injured retinas of heat shocked hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish.

Figure 3.

Forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a in the uninjured retina lowers the proliferative threshold of MG proliferation response to growth factor stimulation. A, Timeline for experiment and representative images of BrdU immunofluorescence in retinal sections from hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a transgenic fish ± heat shock and growth factor treatment. Scale bar, 50 μm. B, Quantification of BrdU immunofluorescence shown in A; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

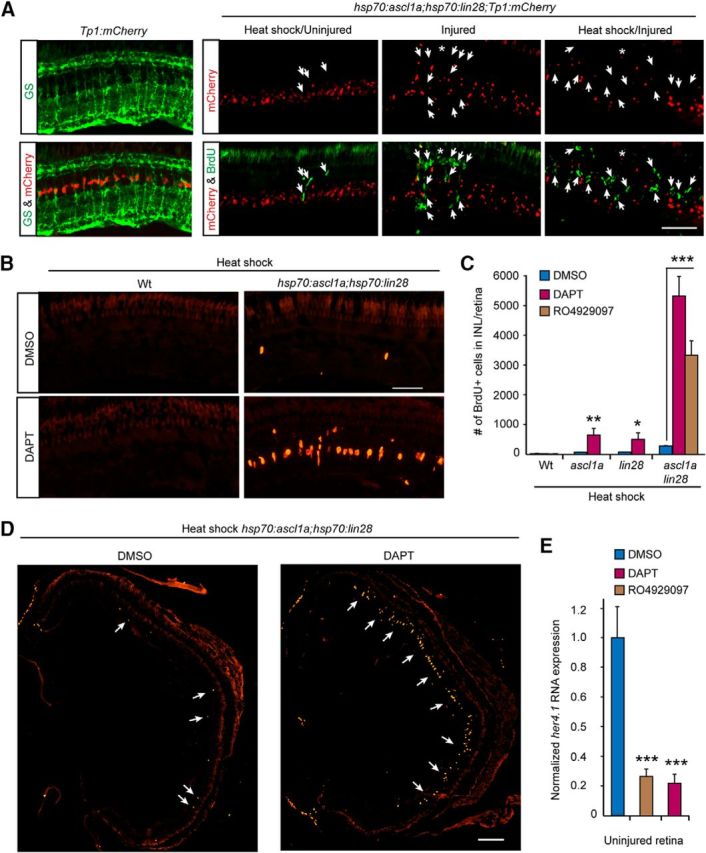

Notch signaling inhibition collaborates with Ascl1a and Lin28a to stimulate MG proliferation in the uninjured fish retina

In contrast to growth factors and cytokines that stimulate MG proliferation, Notch signaling is associated with MG quiescence and inhibits injury-dependent MG proliferation (Wan et al., 2012; Conner et al., 2014; Wan and Goldman, 2017). Therefore, we wondered whether this Notch-driven inhibitory environment may be contributing to the relatively small effect of Ascl1a and Lin28a expression on MG proliferation in the uninjured retina. Notch signaling was visualized in Tp1:mCherry transgenic fish that harbor 12 RBP-Jk binding sites upstream of a minimal promoter that drives nuclear localized mCherry expression (Parsons et al., 2009). In the uninjured retina of Tp1:mCherry fish, mCherry expression is restricted to quiescent MG (Fig. 4A). To investigate whether Ascl1a and Lin28a-dependent MG proliferation is associated with Notch signaling inhibition, we bred hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a double-transgenic fish with Tp1:mCherry transgenic fish. Heat shock of uninjured or injured hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a;Tp1:mCherry fish showed Notch signaling was repressed in proliferating MG regardless of whether the stimulus to proliferate was forced Ascl1a and Lin28a expression, retinal injury, or a combination of both (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Ascl1a and Lin28a expression synergize with Notch signaling inhibition to stimulate MG proliferation throughout the uninjured retina. A, Left, mCherry expression and GS immunofluorescence (green) in uninjured retinas of Tp1:mCherry fish and indicate that Notch signaling is confined to quiescent MG. Remaining panels show that MG proliferation (BrdU+; green signal) stimulated by forced Ascl1a and Lin 28 expression in the uninjured and injured retina of hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a;Tp1:mCherry triple-transgenic fish is accompanied by reduced mCherry expression (red). Scale bar, 50 μm. B, BrdU immunofluorescence (red) shows that forced Ascl1a and Lin28a expression synergizes with DAPT-treatment to stimulate MG proliferation (BrdU+) in the INL of uninjured retinas. Scale bar, 50 μm. C, Quantification of BrdU+ cells in Wt, hsp70:ascl1a, hsp70:lin28a, and hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a fish treated with heat shock, ± DAPT or RO4929097; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. D, BrdU immunofluorescence shows that forced Ascl1a and Lin28a expression synergizes with DAPT-treatment to stimulate MG proliferation (BrdU+) throughout the INL of uninjured retinas. Scale bar, 150 μm. E, qPCR quantification of her4.1 gene expression in uninjured retinas treated with DMSO, DAPT, or RO4929097; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. ***p < 0.001.

Although loss of Notch signaling is associated with MG proliferation, we recently reported that Notch inhibition is not sufficient to stimulate MG proliferation in the uninjured retina (Wan and Goldman, 2017). Indeed, immersing uninjured fish in water containing the Notch signaling inhibitor DAPT for 4 d had little effect on MG proliferation in the uninjured retina (Fig. 4B,C). However, if DAPT-treatment was combined with forced expression of Ascl1a and/or Lin28a, MG proliferation ensued and this was most dramatic in fish expressing both Ascl1a and Lin28a together (Fig. 4B–D). We previously reported that DAPT suppresses mCherry expression in MG of Tp1:mCherry transgenic fish (Wan and Goldman, 2017). Consistent with this, we find that DAPT also inhibited her4.1 gene expression in the uninjured retina (Fig. 4E). Similar results were obtained with a second Notch signaling inhibitor, RO4929097 that was delivered into the vitreous (Fig. 4C,E). These data, along with our previous studies (Wan et al., 2012; Wan and Goldman, 2017), suggest that MG quiescence is driven/maintained by Notch signaling and that this signaling must be relieved for MG proliferation to occur. Importantly, our data suggest that in conjunction with Notch inhibition, Ascl1a and Lin28a are sufficient to stimulate MG proliferation.

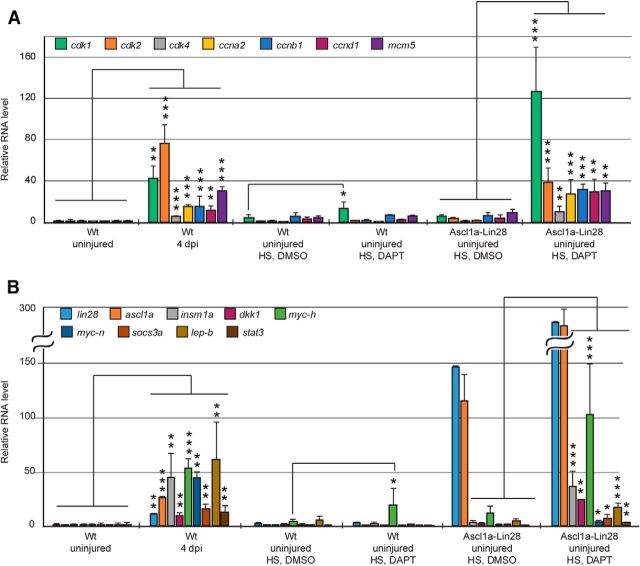

Regulation of regeneration-associated genes following DAPT-treatment and Ascl1a/Lin28a expression

Zebrafish MG respond to retinal injury by acquiring characteristics of a retinal stem cell and this is associated with changes in gene expression (Kassen et al., 2007; Qin et al., 2009; Ramachandran et al., 2012; Sifuentes et al., 2016). These regeneration-associated gene expression changes include those that are associated with somatic cell reprogramming, cell-cycle regulation and other events that are associated with the response of MG to an injured retinal environment (Kassen et al., 2008; Ramachandran et al., 2010b, 2012; Thomas et al., 2016). We wondered whether gene expression programs driving MG proliferation in the injured retina were shared with those driving MG proliferation in the uninjured, DAPT/Ascl1a/Lin28a-treated retina. For this analysis we quantified the expression of select injury-responsive genes whose induction is necessary for MG proliferation in the injured retina (Fig. 5). Interestingly, except for cdk1 and mych, all of these regeneration-associated genes retained basal expression levels after either DAPT-treatment or forced expression of Ascl1 and Lin28a; however, when these treatments were combined, a dramatic increase in the expression of these genes was noted (Fig. 5). Together with previous studies (Wan et al., 2012; Wan and Goldman, 2017), our data suggest that Notch signaling drives a quiescence program that impinges on regeneration-associated genes and that Notch signaling must be relieved in order for MG to proliferate. Furthermore, neither Notch inhibition alone nor the activation of regeneration-associated genes, like ascl1a and lin28a, is sufficient to activate a program of gene expression that drives MG proliferation; rather Notch inhibition must be combined with injury-related factors, like Ascl1a and Lin28a, to fully activate a regeneration-associated gene expression program.

Figure 5.

Ascl1a and Lin28a expression synergize with Notch signaling inhibition to stimulate regeneration-associated gene expression. A, B, qPCR quantification of cell-cycle related genes (A) and reprogramming-associated genes (B) in Wt and hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a fish retinas treated as indicated. HS, Heat shock. n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

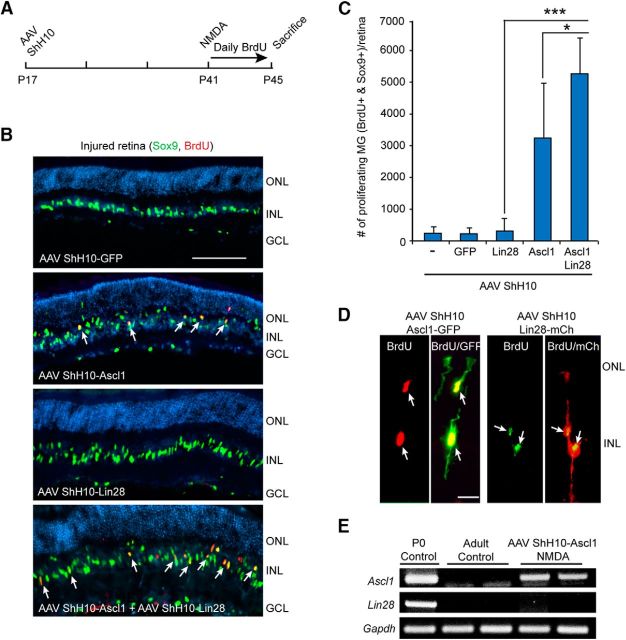

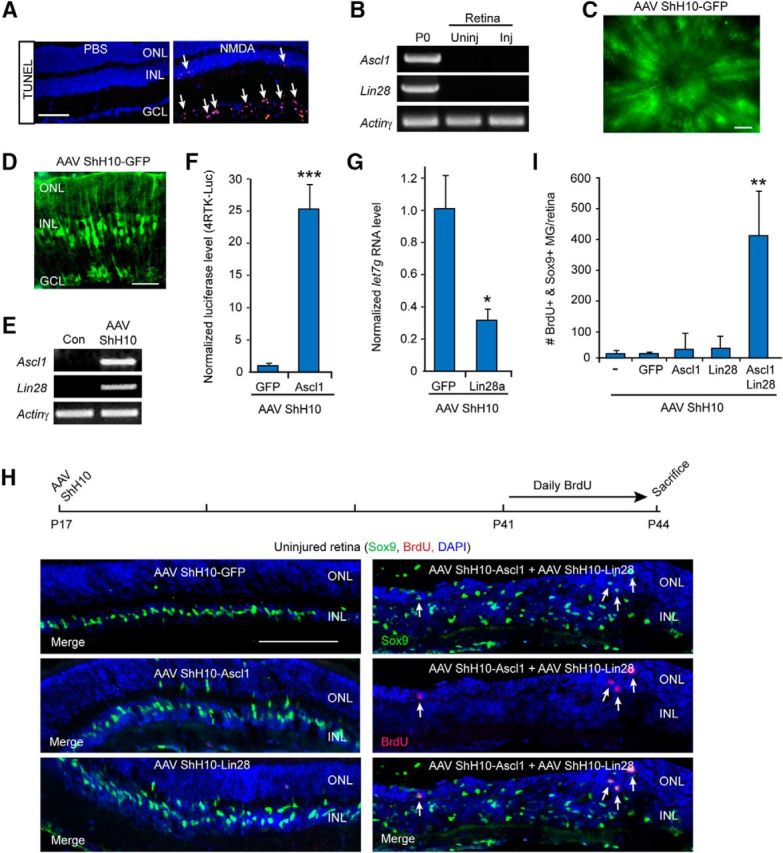

Ascl1 and Lin28a synergize to stimulate MG proliferation in the uninjured mouse retina

Because forced Ascl1a and Lin28a expression in the uninjured fish retina was sufficient to drive a small amount of MG proliferation (Fig. 1G,H), we wondered whether they would have a similar effect in mice where MG proliferation and retina regeneration does not occur. Before investigating the consequence of Ascl1 and Lin28a on MG proliferation in the mouse retina, we examined whether Ascl1 and Lin28a RNAs are expressed in the uninjured and injured retina. For this analysis, retinas were injured by intravitreal injection of NMDA, which predominantly ablates RGCs (Fig. 6A). Unlike their injury-dependent induction in the fish retina, Ascl1 and Lin28a RNAs remain undetectable in the uninjured and injured mouse retina (Fig. 6B). However, Ascl1 and Lin28a were detected in P0 retina and brain, respectively, which served as positive controls (Fig. 6B). To investigate whether Ascl1 and Lin28a could stimulate MG proliferation in the mouse retina, we took advantage of AAV ShH10 to deliver genes encoding GFP, Ascl1 and/or Lin28a to MG (Klimczak et al., 2009; Byrne et al., 2013). Intravitreal injection of AAV ShH10-GFP efficiently delivered the transgene constructs to MG (Fig. 6C,D) and PCR confirmed expression of Ascl1 and Lin28a RNAs (Fig. 6E). We determined that AAV ShH10-Ascl1 and AAV ShH10-Lin28a produced functional proteins by infecting HEK 293 cells and assaying their effects on a transfected 4RTK-Luc reporter construct (Weintraub et al., 1990), and on endogenous let7 microRNA levels (Rybak et al., 2008; Heo et al., 2009), respectively (Fig. 6F,G). Infection of HEK293 cells with AAV ShH10-Ascl1 resulted in ∼25-fold increase in 4RTK-Luc reporter activity (Fig. 6F), whereas infection with AAV ShH10-Lin28a reduced let7g RNA levels by >60% (Fig. 6G).

Figure 6.

Ascl1 and Lin28a expression synergize with each other to stimulate MG proliferation in the uninjured mouse retina. A, TUNEL stain (red) shows NMDA stimulates cell death in the GCL. Scale bar, 100 μm. B, PCR shows Ascl1 and Lin28a are detectable in the P0 retina and brain, respectively, but not in the uninjured or NMDA damaged (Inj) adult retina. C, GFP fluorescence in flat mount retina shows AAV ShH10-GFP expression throughout the uninjured retina. Scale bar, 100 μm. D, GFP immunofluorescence on retinal sections shows AAV ShH10-GFP expression in MG of the uninjured retina. Scale bar, 50 μm. E, PCR shows Ascl1 and Lin28a expression in retinas transduced with AAV ShH10-Ascl1 and AAV ShH10-Lin28a. F, Luciferase assays show HEK293 cells transfected with 4RTK-Luc and transduced with AAV ShH10-Ascl1 result in increased expression of the 4RTK-Luc reporter indicating expression of a functional Ascl1 protein; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. ***p < 0.001. G, Transduction of HEK293 cells with AAV ShH10-Lin28a result in reduced let7g expression consistent with expression of a functional Lin28a protein; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. *p < 0.05. H, Timeline of experiment and representative images of AAV ShH10-Ascl1 and AAV ShH10-Lin28a infected retinas showing Ascl1 and Lin28a synergize to stimulate some MG proliferation (Sox9+/BrdU). Sox9+ MG are labeled green and proliferating BrdU+ cells are labeled red. DAPI labels cell nuclei blue. Scale bar, 100 μm. I, Quantification of data shown in H shows Ascl1 and Lin28a synergize to stimulate MG proliferation in the uninjured retina; n = 4 different experiments. Error bars are SD. **p < 0.01.

To investigate whether forced expression of Ascl1 and Lin28a could stimulate MG proliferation in the uninjured adult mouse retina, we injected AAV ShH10-GFP, AAV ShH10-Ascl1, AAV ShH10-Lin28a, or a combination of these viruses into the vitreous of P17 mouse eyes. Three and one-half weeks later, mice received daily injections of BrdU for 4 d before kill. Retinal sections were then prepared and BrdU and Sox9 immunofluorescence was used to assay cell proliferation and identify MG, respectively. Although overexpression of Ascl1 or Lin28a, individually, had no effect on MG proliferation (Fig. 6H,I), they did result in a small amount of MG delamination (Fig. 6H). In contrast, we noted an increase in MG proliferation and delamination when Ascl1 and Lin28a were coexpressed (Fig. 6H,I). Quantification of BrdU+/Sox9+ MG suggests this proliferation represents <1% of the total Sox9+ MG population (∼170,000/retina). Nonetheless, these data suggest that similar to their action in the fish retina, Ascl1 and Lin28a synergize with each other to stimulate a small amount of MG proliferation in the uninjured mouse retina.

Ascl1-dependent MG proliferation in the injured mouse retina is enhanced by Lin28a expression

Ascl1a and Lin28a collaborate with injury-derived factors to stimulate MG proliferation in the injured fish retina (Fig. 2A–C). To investigate whether Ascl1 and Lin28a had a similar effect in the injured mouse retina, we infected retinas with AAV ShH10-Ascl1 and/or AAV ShH10-Lin28a at P17; damaged retinas with NMDA at P41; and then gave daily BrdU injections for 4 d to label proliferating cells (Fig. 7A). Consistent with a previous report (Ueki et al., 2015), Ascl1 expression in the NMDA damaged retina was sufficient to stimulate a small amount of MG proliferation (Fig. 7B,C). Interestingly, this proliferation was further enhanced by Lin28a coexpression (Fig. 7B,C). The effect of Ascl1 and Lin28a on MG proliferation in the injured retina was >10-fold more than that observed in the uninjured retina, suggesting interaction with injury-responsive factors similar to what we noted in the injured fish retina.

Figure 7.

Ascl1-dependent MG proliferation in the injured mouse retina is enhanced by Lin28a expression. A, Experimental timeline. B, Sox9 and BrdU immunofluorescence on retinal sections from injured retinas shows forced expression of Ascl1 stimulates a small amount of MG proliferation that is enhanced when combined with Lin28a expression injured retina. Scale bar, 100 μm. C, Quantification of proliferating MG in injured retinas that were infected with the indicated AAV ShH10 virus; n = 5 different experiments. Error bars are SD. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. D, P17 mouse retinas were infected with either AAV ShH10-Ascl1-GFP or AAV ShH10-Lin28a-mCherry and then treated with NMDA and BrdU, and killed as indicated in A. BrdU/GFP or BrdU/mCherry immunofluorescence on retinal section showed BrdU+ MG expressed Ascl1-GFP or Lin28a-mCherry (Lin28a-mCh), respectively. Scale bar, 100 μm. E, PCR shows retinas infected with AAV ShH10-Ascl1 express Ascl1, but do not activate the endogenous Lin28a gene.

We used GFP and mCherry tagged versions of Ascl1 and Lin28a, respectively, to determine whether proliferating cells harbored virally transduced genes (Fig. 7D). Because AAV ShH10-Ascl1 is sufficient to stimulate MG proliferation (Fig. 7C), we quantified the number of BrdU+ MG infected with virus. Interestingly, we found that only ∼47% of the BrdU+ MG was associated with viral-mediated transgene expression. This might suggest that Ascl1 can act in a cell nonautonomous fashion or, alternatively, may reflect our limits in detecting virus encoded transgenes. Finally, we note that although a previous study indicated that Lin28a expression was sufficient to drive MG proliferation (Yao et al., 2016), in our hands Lin28a infection alone had no discernable effect on MG proliferation (Fig. 6H,I). The reason for this difference is not known, but may reflect differences in Lin28a expression levels resulting from the use of different gene promoters.

Because Ascl1 and Lin28a synergize to stimulate MG proliferation in the uninjured fish and mouse retina, we went on to examine whether the effect of Ascl1 expression on MG proliferation in the injured mouse retina resulted from induction of the endogenous Lin28a gene. To investigate this possibility, retinas were transduced by intravitreal AAV ShH10-Ascl1 and 3.5 weeks later mice received intravitreal injections of NMDA. Retinas were harvested 4 d later and Ascl1 and Lin28a gene expression assayed by PCR. This analysis indicated Ascl1 expression does not stimulate widespread Lin28a expression in the injured mouse retina (Fig. 7E). We note that two Ascl1 consensus binding sites exist upstream of the mouse Lin28a gene's transcription start site, but their functional significance remains unexplored. Thus, consistent with a previous report (Ueki et al., 2015), we found that forced expression of Ascl1 is sufficient to stimulate MG proliferation in the injured mouse retina; however, our data suggest that this can be enhanced by combining Ascl1 with Lin28a expression.

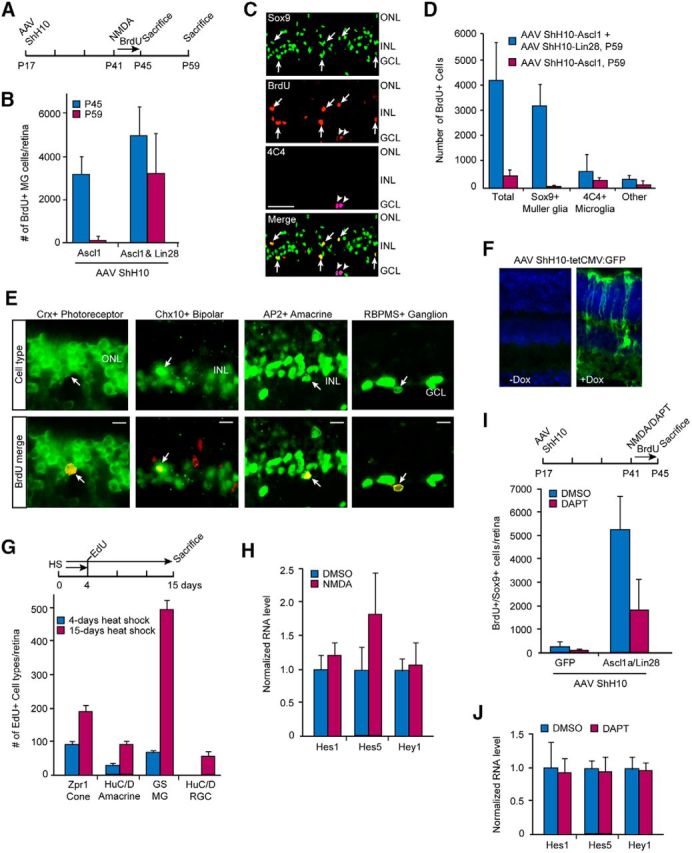

Ascl1 and Lin28a enhance survival of proliferating MG and allow reprogramming to multipotency

Our data indicated that Lin28a expression can enhance Ascl1-dependent MG proliferation. We next investigated whether the survival of MG stimulated to proliferate by Ascl1 expression was altered by Lin28a expression. For this analysis, P17 mice received an intravitreal injection of AAV ShH10-Ascl1 or a mixture of AAV ShH10-Ascl1 and AAV ShH10-Lin28a. At P41, mice received an intravitreal injection of NMDA and BrdU followed by daily intraperitoneal injections of BrdU for 4 d; mice were then killed at either P45 or P59 (Fig. 8A). Interestingly, when we compared the number of double-labeled BrdU+/Sox9+ MG cells at P45 with those at P59 we found many more persisted when expressing both Ascl1 and Lin28a compared with those expressing Ascl1 alone (Fig. 8B). However, the fact that most BrdU+/Sox9+ cells remained Sox9+ two weeks after BrdU labeling and were concentrated in the INL suggested that these cells retain MG characteristics (Fig. 8C). Quantification showed that these cells represent ∼76% of the total BrdU population in the INL and ONL (Fig. 8C,D). Although many BrdU+/Sox9− cells were located on the vitreal side of the GCL and expressed the microglia marker 4C4 (Fig. 8C), only ∼16% of the BrdU+ cells in the INL and ONL were 4C4+ microglia (Fig. 8D). Of the remaining (∼8%) BrdU+ cells in these retinal layers (Fig. 8D, “other”), co-immunofluorescence showed some expressed markers for photoreceptors (Crx), amacrine cells (AP2), bipolar cells (Chx10), and RGCs (RBPMS; Fig. 8E).

Figure 8.

Ascl1 and Lin28a expression enhances survival of proliferating MG and regenerate multiple neuron types in the injured retina. A, Experimental timeline. B, Lin28a expression when combined with Ascl1 expression enhances survival of proliferating MG in the injured retina compared with Ascl1 expression alone. Sox9 and BrdU immunofluorescence on retinal sections were used to quantify MG proliferation; n = 5 different experiments. Error bars are SD. C, Representative images of lineage traced BrdU+ cells in the injured retina suggests that most proliferating cells in the Ascl1- and Lin28a-expressing retina are Sox9+ MG (arrows). Arrowheads indicate 4C4+ microglia. Scale bar, 50 μm. D, Quantification of data shown in C; n = 5 different experiments. Error bars are SD. E, Lineage tracing experiments were performed as indicated in A and BrdU+ cells (red) with cell-type-specific markers (green) of photoreceptors (Crx), bipolar (Chx10), amacrine (AP2), and ganglion cells (RBPMS) are indicated by arrows. F, Dox-dependent expression of GFP in eyes that received intravitreal injection of a mixture of AAV ShH10-tetCMV:GFP, AAV ShH10-tetCMV:Ascl1, and AAV ShH10-tetCMV:Lin28a. G, Timeline and quantification of lineage trace experiment in hsp70:ascl1a;hsp70:lin28a fish treated with heat shock for 4 or 15 d when using EdU labeling at 4 d post-heat shock. Retinal cell-type antibodies were used to quantify the number of Edu+ cells that costain with cone (Zpr1), MG (GS), amacrine cell (HuC/D in INL), and RGC (in RGC layer) antibodies; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. H, NMDA has no effect on Notch-responsive genes in the uninjured retina; n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD. I, DAPT-treatment inhibits MG proliferation in injured retinas expressing Ascl1 and Lin28a. Top illustration is timeline of experiment and graph quantifies the number of Sox9+ and BrdU+ double-labeled cells/retina; n = 5 different experiments. Error bars are SD. J, DAPT treatment has no effect on Notch-responsive genes in the uninjured AAV ShH10 Ascl1 and AAV ShH10 Lin28a transduced retina. n = 3 different experiments. Error bars are SD.

Effects of transient versus sustained Ascl1 and Lin28a expression in fish and mice

Our data suggested that constitutive expression of Ascl1 and Lin28a in mice stimulates MG proliferation in the injured retina, but only a very small fraction of these proliferating cells differentiate into retinal neurons (Fig. 8D,E). During development Ascl1 and Lin28a are transiently expressed in stem-cell populations and suppressed as differentiation proceeds (Jasoni and Reh, 1996; Xu et al., 2009). To investigate whether transient expression of Ascl1 and Lin28a facilitate differentiation of MG-derived progenitors, we generated AAV ShH10-tetCMV expression vectors driving Ascl1, Lin28a, and GFP using an optimized Tet-On system (V10; Zhou et al., 2006). These vectors harbor a minimal CMV promoter controlled by rtTA and allow for conditional transgene expression. A mixture of these viruses was injected into the eye's vitreous of P17 mice. At P41, mice received an intravitreal injection of doxycycline (2 μl of 4 μg/μl) 1 d before the standard NMDA injury. A second intravitreal injection of doxycycline was performed 2 d after the NMDA treatment. For these experiments EdU was substituted for BrdU and lineage tracing experiments were performed as described above with progenitor differentiation assayed on P59. Although we confirmed doxycycline-dependent transgene induction in vivo in MG (Fig. 8F), we did not observe any significant effect on progenitor differentiation.

We next compared the effects of transient (4 d) with sustained (15 d) Ascl1a and Lin28a expression on progenitor differentiation in fish. For this analysis, we exposed fish to either a 4 or 15 d heat shock paradigm with an intraperitoneal injection of EdU at day 4 and then killed 11 d later (Fig. 8G). This experiment revealed more differentiated progenitors with sustained Ascl1a and Lin28a expression at 15 d of heat shock. Analysis of the fraction of proliferating MG that retain MG characteristics (GS+), indicate ∼59% with sustained heat shock and ∼34% with transient heat shock, which is consistent with the idea that sustained Ascl1a and Lin28a expression inhibited progenitor differentiation. Nonetheless, this was a relatively small effect and it did not reduce the amount of progenitor differentiation to the very low levels observed in mice. This suggests that additional factors will be required for enhancing MG proliferation and differentiation in mice.

Ascl1 and Lin28a-dependent MG proliferation and differentiation is not enhanced by Notch inhibition in the mouse retina

Our data suggest that forced expression of Ascl1 and Lin28a can stimulate a small amount of MG proliferation in the fish and mouse retina (Figs. 1G,H, 7B,C; 8D,E). In fish, this proliferation can be greatly enhanced by Notch signaling inhibition (Fig. 4). Therefore, we investigated whether Notch inhibition in the mouse retina would also enhance Ascl1 and Lin28a-dependent MG proliferation. Notch signaling is low, but detectable in MG residing in the p21 mouse retina (Nelson et al., 2011; Riesenberg et al., 2018). To determine whether this residual Notch signaling was suppressed following retinal injury, we assayed the expression of Notch target genes, Hes1, Hes5, and Hey1, and found no significant change following NMDA-induced retinal damage (Fig. 8H). We next investigated whether the residual Notch signaling observed in adult mouse retinas influenced Ascl1/Lin28a-induced proliferation after injury. For this analysis, P17 Wt mice received intravitreal injections of AAV ShH10-Ascl1 and AAV ShH10-Lin28a. At P41 mice received BrdU, ±NMDA as described in the previous section; however, mice also received intravitreal injections of DAPT or vehicle for the 4 d following NMDA treatment (Fig. 8I). Retinal sections were then assayed for BrdU and Sox9 co-immunofluorescence. This analysis showed that although DAPT had no effect on MG proliferation in the uninjured retina (data not shown), it suppressed MG proliferation in the injured retina (Fig. 8I). However, this effect was not correlated with changes in the expression of Notch reporter genes Hes1, Hes5, and Hey1 (Fig. 8J). Thus, Notch reporter gene expression may not reflect small changes in Notch signaling in the adult mouse retina where Notch signaling is already at a low level (Nelson et al., 2011; Riesenberg et al., 2018). Furthermore, we cannot rule out the possibility that the anti-proliferative effect of DAPT may be a consequence of inhibiting a γ-secretase unrelated to Notch signaling.

During retina development Notch signaling is increased in progenitors that acquire a MG fate (Furukawa et al., 2000). We wondered whether the reduced number of BrdU+ MG noted following retinal damage and DAPT treatment (Fig. 8I) reflected a loss of glial identity and enhanced neuronal differentiation. For this analysis, we used DNMAML mice that allow for Cre-mediated expression of a dominant-negative mastermind-like protein and should allow us to maintain Notch inhibition over prolonged periods (Maillard et al., 2006). DNMAML mice were treated as described in Figure 8A except that at P27 the left eye received an intravitreal injection of AAV ShH10-Cre, whereas the contralateral control eye received a PBS vehicle injection. At P55, mice were killed and retinas sectioned and immunofluorescence used to assay for BrdU+ cells that coexpress retinal neuron-specific markers. This analysis revealed no significant effect of DNMAML on MG-derived progenitor differentiation. Altogether, our studies suggest Notch signaling inhibitors have little effect on neural differentiation of MG-derived progenitors in the adult mouse retina.

Discussion

Fish and amphibians have remarkable regenerative powers that provide us with an opportunity to understand this process at the cellular and molecular level. In the zebrafish retina, MG are a source of retinal progenitors used to repair a damaged retina (Goldman, 2014; Wan and Goldman, 2016). It is anticipated that identification of the molecular strategies underlying MG reprogramming and the acquisition of stem-cell properties may suggest strategies for stimulating these events in mammals. Here we report that forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a can stimulate sparse MG proliferation and retinal neuron regeneration in both fish and mice. Interestingly, when this expression was combined with Notch signaling inhibition, only in the fish retina did we observe a large increase in MG proliferation.

Ascl1a and Lin28a are potent regulators of zebrafish retina regeneration and appear to coordinate the expression of many genes critical for MG reprogramming and proliferation (Fausett et al., 2008; Ramachandran et al., 2010b, 2011, 2012; Nelson et al., 2012, 2013; Wan et al., 2012, 2014; Gorsuch et al., 2017). Ascl1 and Lin28a are also mammalian reprogramming factors that can convert fibroblasts and astrocytes to neurons and participate in converting somatic cells to pluripotent stem cells, respectively (Yu et al., 2007; Chanda et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015). Despite these characteristics, forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a did not lead to widespread MG proliferation in the uninjured fish retina. We wondered whether this lack of proliferation resulted from antiproliferative signals that MG receive in the uninjured retinal environment. A candidate signaling pathway that might convey these anti-proliferative signals to the MG genome was Notch signaling, which is restricted to quiescent MG and must be suppressed in order for MG proliferation to ensue (Wan et al., 2012; Conner et al., 2014; Wan and Goldman, 2017). Indeed, when Ascl1a and Lin28a expression was combined with Notch inhibition, widespread MG proliferation was noted.

The observation that Ascl1a and Lin28a expression and Notch inhibition together, but not individually, stimulated MG proliferation suggested they act in parallel pathways that converge on genes that drive MG proliferation and retina regeneration. Although Notch signaling generally leads to gene activation, we recently reported that forced activation of Notch signaling in the injured retina represses genes associated with MG reprogramming and proliferation (Wan and Goldman, 2017). This repression might be mediated by Notch-target genes, like the hes/her/hey gene family of repressors which are known to regulate neural stem-cell maintenance (Kageyama et al., 2007; Imayoshi et al., 2010; Imayoshi and Kageyama, 2011). Indeed, we found that hey1 and her4.1 gene expression can be activated by Notch signaling in fish MG (Wan et al., 2012; Wan and Goldman, 2017). Furthermore, Hey1 expression has been associated with gliogenesis and inhibition of Ascl1 expression in the mammalian brain (Sakamoto et al., 2003). Thus, our studies suggest that individually, Notch inhibition and Ascl1/Lin28a expression contribute to different aspects of MG activation that must be combined to fully unleash a regeneration-associated gene expression program. Identifying the genetic underpinnings of these activated states may be crucial for devising strategies to stimulate a robust regenerative response in mammals.

Although spontaneous MG proliferation is very low in the uninjured fish retina, it does occur, and is responsible for generating rod progenitors that help maintain a constant rod density as the retina expands throughout the fish's life (Johns and Fernald, 1981; Otteson and Hitchcock, 2003; Bernardos et al., 2007). Our studies suggest that enhancing spontaneous MG proliferation with forced Ascl1a and Lin28a expression stimulates the formation of multipotent progenitors. Although it is not known whether MG that generate unipotent rod progenitors are different from those that make multipotent progenitors, it is noteworthy that we recently identified a heterogeneous population of MG in the zebrafish retina (Wan and Goldman, 2017). The differences in MG responsiveness to forced expression of Ascl1a and Lin28a in the uninjured and injured retina may also reflect MG heterogeneity.

Based on the robust effect that Notch signaling inhibition combined with forced Ascl1a and Lin28a expression had on MG proliferation in the uninjured fish retina, we investigated whether they would have a similar consequence on MG proliferation and neuron regeneration in the mouse where retina regeneration does not normally occur. Similar to the observation that Ascl1 expression can stimulate a small amount of MG proliferation in the injured postnatal mouse retina (Ueki et al., 2015), we found Ascl1-dependent MG proliferation in the injured adult retina. Interestingly, this was independent of Lin28a induction. However, our studies suggested that in the absence of Lin28a, most of these cells do not persist. We did not observe an effect of Lin28a on MG proliferation in the injured mouse retina and this is consistent with what we observed in fish; however, our results are different from a recent study in mice where Lin28a was reported to stimulate MG proliferation (Yao et al., 2016). The reason for this difference is not known, but may be related to the level of Lin28a expression because different promoters were used in these two studies. Nonetheless, like that observed in fish, combined expression of Ascl1 and Lin28a in the mouse retina was sufficient to stimulate a small amount of MG proliferation in the uninjured retina that was enhanced by retinal injury. These similarities in response to Ascl1 and Lin28a are encouraging; however, differences between fish and mice were also noted. First, in the injured mouse retina, Ascl1 stimulated a small amount of MG proliferation, whereas no enhancement of MG proliferation was noted in fish. Second, Lin28a enhanced survival of proliferating MG in mice, whereas it collaborated with Ascl1a to stimulate MG proliferation in fish. Third, Ascl1 and Lin28a-dependent MG proliferation in mice only rarely generated neurons, whereas in fish, neuronal regeneration was more prevalent. Finally, the low levels of basal Notch signaling in the adult mouse retina appears somewhat resistant to pharmacological or genetic means of reduction, which was indicated by Notch-responsive genes. However, it is possible that these genes remain elevated by intrinsic regulators, like Lhx2 (de Melo et al., 2016a,b). Regardless, attempts to reduce Notch signaling did not enhance Ascl1 and Lin28a-dependent MG proliferation in the uninjured or injured mouse retina; however, in the uninjured fish retina, Notch signaling is relatively high in MG and its inhibition, when combined with Ascl1a and Lin28a expression, dramatically stimulated widespread MG proliferation. This latter effect seems to be a major difference between fish and mice and understanding its roots may help devise strategies for recruiting MG to a regenerative response in mammals.

In addition to generating retinal progenitors through cell division, MG can transdifferentiate into bipolar cells after overexpression of Ascl1 and treatment with the histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin-A (TSA; Jorstad et al., 2017). This transdifferentiation process occurs in adult mice and is not dependent on MG proliferation. Although the consequences of reducing the MG population by transdifferentiation is not known, it may have a detrimental effect on retinal structure and function. Regardless, because Lin28a impacts the survival of MG stimulated to proliferate by Ascl1 in the injured retina, it would be interesting to investigate whether Lin28a also affects MG transdifferentiation. Importantly, the combinatorial action of Ascl1 and TSA on MG reprogramming for transdifferentiation highlights the impact chromatin modifying agents can have on stimulating gene expression programs normally suppressed in a differentiated cell type. The potential for these agents to help reprogram MG to generate progenitors for retinal repair is intriguing and is an area for future studies.

In summary, our research identified key components underlying zebrafish retina regeneration that are sufficient to stimulate this process in the uninjured fish retina. Some of these components, like Ascl1 and Lin28a, were also able to stimulate a small amount of MG proliferation and neuron regeneration in mice. Remarkably, Notch signaling inhibition synergizes with Ascl1a and Lin28a expression to stimulate widespread MG proliferation in fish, but not mice. This lack of synergy in mice may reflect our inability to inhibit basal levels of Notch signaling, which are already very low. Although sustained expression of NICD can inhibit MG proliferation (Wan et al., 2012), we recently reported that the cessation of Notch signaling following forced and transient NICD expression stimulates MG proliferation in the injured fish retina (Wan and Goldman, 2017). It is tempting to speculate that cessation of Notch signaling may also be critical for stimulating MG proliferation in the injured mammalian retina; perhaps one will need to enhance Notch signaling in mammals to see an effect of its cessation. Furthermore, Notch signaling may regulate different genes in fish and mice, and identification of these differences may suggest additional strategies for enhancing mammalian MG proliferation. Finally, many gene products and signaling molecules have been found to regulate retina regeneration in zebrafish (Goldman, 2014; Wan and Goldman, 2016) and these provide a rich resource for testing in mammals. It is anticipated that some of these molecules will collaborate with Ascl1 and Lin28a to stimulate retina regeneration in mammals.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants from the NIH (NEI RO1 EY018132 and NEI RO1 EY027310 to D.G., NEI R01 EY022975 to J.G.F., and Kirschstein NRSA T32HD007505-20 to E.A.M.), a Research to Prevent Blindness Innovative Ophthalmic Research Award and gifts from the Marjorie and Maxwell Jospey Foundation and the Shirlye and Peter Helman Fund to D.G., and the Foundation Fighting Blindness and the Lowy Medical Research Institute to J.G.F. We thank Curtis Powell for generating hsp70:ascl1a and hsp70:lin28a transgenic zebrafish, Curtis Powell and Rahaman Gangji for preliminary characterization of hsp70:ascl1a and hsp70:lin28a transgenic lines, Michael Parsons (Johns Hopkins University) for tp1:mCherry transgenic fish, Ivan Maillard (UM) for providing DN-MAML mice, and Joshua Kirk for maintaining our zebrafish colony.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Barthel LK, Raymond PA (2000) In situ hybridization studies of retinal neurons. Methods Enzymol 316:579–590. 10.1016/S0076-6879(00)16751-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardos RL, Barthel LK, Meyers JR, Raymond PA (2007) Late-stage neuronal progenitors in the retina are radial Müller glia that function as retinal stem cells. J Neurosci 27:7028–7040. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1624-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne LC, Khalid F, Lee T, Zin EA, Greenberg KP, Visel M, Schaffer DV, Flannery JG (2013) AAV-mediated, optogenetic ablation of Müller glia leads to structural and functional changes in the mouse retina. PLoS One 8:e76075. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chanda S, Ang CE, Davila J, Pak C, Mall M, Lee QY, Ahlenius H, Jung SW, Südhof TC, Wernig M (2014) Generation of induced neuronal cells by the single reprogramming factor ASCL1. Stem Cell Reports 3:282–296. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner C, Ackerman KM, Lahne M, Hobgood JS, Hyde DR (2014) Repressing notch signaling and expressing TNFα are sufficient to mimic retinal regeneration by inducing Müller glial proliferation to generate committed progenitor cells. J Neurosci 34:14403–14419. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0498-14.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Melo J, Clark BS, Blackshaw S (2016a) Multiple intrinsic factors act in concert with Lhx2 to direct retinal gliogenesis. Sci Rep 6:32757. 10.1038/srep32757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Melo J, Zibetti C, Clark BS, Hwang W, Miranda-Angulo AL, Qian J, Blackshaw S (2016b) Lhx2 is an essential factor for retinal gliogenesis and notch signaling. J Neurosci 36:2391–2405. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3145-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausett BV, Goldman D (2006) A role for α1 tubulin-expressing Müller glia in regeneration of the injured zebrafish retina. J Neurosci 26:6303–6313. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0332-06.2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausett BV, Gumerson JD, Goldman D (2008) The proneural basic helix-loop-helix gene ascl1a is required for retina regeneration. J Neurosci 28:1109–1117. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4853-07.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flannery JG, Visel M (2013) Adeno-associated viral vectors for gene therapy of inherited retinal degenerations. Methods Mol Biol 935:351–369. 10.1007/978-1-62703-080-9_25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T, Mukherjee S, Bao ZZ, Morrow EM, Cepko CL (2000) rax, Hes1, and notch1 promote the formation of Müller glia by postnatal retinal progenitor cells. Neuron 26:383–394. 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81171-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman D. (2014) Muller glial cell reprogramming and retina regeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci 15:431–442. 10.1038/nrn3723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorsuch RA, Lahne M, Yarka CE, Petravick ME, Li J, Hyde DR (2017) Sox2 regulates Müller glia reprogramming and proliferation in the regenerating zebrafish retina via Lin28 and Ascl1a. Exp Eye Res 161:174–192. 10.1016/j.exer.2017.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo I, Joo C, Kim YK, Ha M, Yoon MJ, Cho J, Yeom KH, Han J, Kim VN (2009) TUT4 in concert with Lin28 suppresses microRNA biogenesis through pre-microRNA uridylation. Cell 138:696–708. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imayoshi I, Kageyama R (2011) The role of Notch signaling in adult neurogenesis. Mol Neurobiol 44:7–12. 10.1007/s12035-011-8186-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imayoshi I, Sakamoto M, Yamaguchi M, Mori K, Kageyama R (2010) Essential roles of notch signaling in maintenance of neural stem cells in developing and adult brains. J Neurosci 30:3489–3498. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4987-09.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasoni CL, Reh TA (1996) Temporal and spatial pattern of MASH-1 expression in the developing rat retina demonstrates progenitor cell heterogeneity. J Comp Neurol 369:319–327. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960527)369:2%3C319::AID-CNE11%3E3.0.CO;2-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johns PR, Fernald RD (1981) Genesis of rods in teleost fish retina. Nature 293:141–142. 10.1038/293141a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorstad NL, Wilken MS, Grimes WN, Wohl SG, VandenBosch LS, Yoshimatsu T, Wong RO, Rieke F, Reh TA (2017) Stimulation of functional neuronal regeneration from Müller glia in adult mice. Nature 548:103–107. 10.1038/nature23283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama R, Ohtsuka T, Kobayashi T (2007) The hes gene family: repressors and oscillators that orchestrate embryogenesis. Development 134:1243–1251. 10.1242/dev.000786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassen SC, Ramanan V, Montgomery JE, T Burket C, Liu CG, Vihtelic TS, Hyde DR (2007) Time course analysis of gene expression during light-induced photoreceptor cell death and regeneration in albino zebrafish. Dev Neurobiol 67:1009–1031. 10.1002/dneu.20362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassen SC, Thummel R, Burket CT, Campochiaro LA, Harding MJ, Hyde DR (2008) The Tg(ccnb1:EGFP) transgenic zebrafish line labels proliferating cells during retinal development and regeneration. Mol Vis 14:951–963. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimczak RR, Koerber JT, Dalkara D, Flannery JG, Schaffer DV (2009) A novel adeno-associated viral variant for efficient and selective intravitreal transduction of rat muller cells. PLoS One 4:e7467. 10.1371/journal.pone.0007467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon HJ, Bhat N, Sweet EM, Cornell RA, Riley BB (2010) Identification of early requirements for preplacodal ectoderm and sensory organ development. PLoS Genet 6:e1001133. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey AE, Powers MK (2007) Visual behavior of adult goldfish with regenerating retina. Vis Neurosci 24:247–255. 10.1017/S0952523806230207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Miao Q, Yuan J, Han S, Zhang P, Li S, Rao Z, Zhao W, Ye Q, Geng J, Zhang X, Cheng L (2015) Ascl1 converts dorsal midbrain astrocytes into functional neurons in vivo. J Neurosci 35:9336–9355. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3975-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maillard I, Tu L, Sambandam A, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Millholland J, Keeshan K, Shestova O, Xu L, Bhandoola A, Pear WS (2006) The requirement for notch signaling at the β-selection checkpoint in vivo is absolute and independent of the pre-T cell receptor. J Exp Med 203:2239–2245. 10.1084/jem.20061020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery JE, Parsons MJ, Hyde DR (2010) A novel model of retinal ablation demonstrates that the extent of rod cell death regulates the origin of the regenerated zebrafish rod photoreceptors. J Comp Neurol 518:800–814. 10.1002/cne.22243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BR, Ueki Y, Reardon S, Karl MO, Georgi S, Hartman BH, Lamba DA, Reh TA (2011) Genome-wide analysis of Müller glial differentiation reveals a requirement for notch signaling in postmitotic cells to maintain the glial fate. PLoS One 6:e22817. 10.1371/journal.pone.0022817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CM, Gorsuch RA, Bailey TJ, Ackerman KM, Kassen SC, Hyde DR (2012) Stat3 defines three populations of Müller glia and is required for initiating maximal Müller glia proliferation in the regenerating zebrafish retina. J Comp Neurol 520:4294–4311. 10.1002/cne.23213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CM, Ackerman KM, O'Hayer P, Bailey TJ, Gorsuch RA, Hyde DR (2013) Tumor necrosis factor-α is produced by dying retinal neurons and is required for Müller glia proliferation during zebrafish retinal regeneration. J Neurosci 33:6524–6539. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3838-12.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otteson DC, Hitchcock PF (2003) Stem cells in the teleost retina: persistent neurogenesis and injury-induced regeneration. Vision Res 43:927–936. 10.1016/S0042-6989(02)00400-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons MJ, Pisharath H, Yusuff S, Moore JC, Siekmann AF, Lawson N, Leach SD (2009) Notch-responsive cells initiate the secondary transition in larval zebrafish pancreas. Mech Dev 126:898–912. 10.1016/j.mod.2009.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell C, Cornblath E, Elsaeidi F, Wan J, Goldman D (2016) Zebrafish Müller glia-derived progenitors are multipotent, exhibit proliferative biases and regenerate excess neurons. Sci Rep 6:24851. 10.1038/srep24851 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Z, Barthel LK, Raymond PA (2009) Genetic evidence for shared mechanisms of epimorphic regeneration in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:9310–9315. 10.1073/pnas.0811186106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajaram K, Harding RL, Hyde DR, Patton JG (2014) miR-203 regulates progenitor cell proliferation during adult zebrafish retina regeneration. Dev Biol 392:393–403. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, Reifler A, Parent JM, Goldman D (2010a) Conditional gene expression and lineage tracing of tuba1a expressing cells during zebrafish development and retina regeneration. J Comp Neurol 518:4196–4212. 10.1002/cne.22448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, Fausett BV, Goldman D (2010b) Ascl1a regulates Müller glia dedifferentiation and retinal regeneration through a lin-28-dependent, let-7 microRNA signalling pathway. Nat Cell Biol 12:1101–1107. 10.1038/ncb2115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, Zhao XF, Goldman D (2011) Ascl1a/Dkk/β-catenin signaling pathway is necessary and glycogen synthase kinase-3β inhibition is sufficient for zebrafish retina regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:15858–15863. 10.1073/pnas.1107220108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramachandran R, Zhao XF, Goldman D (2012) Insm1a-mediated gene repression is essential for the formation and differentiation of Müller glia-derived progenitors in the injured retina. Nat Cell Biol 14:1013–1023. 10.1038/ncb2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riesenberg AN, Conley KW, Le TT, Brown NL (2018) Separate and coincident expression of Hes1 and Hes5 in the developing mouse eye. Dev Dyn 247:212–221. 10.1002/dvdy.24542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rybak A, Fuchs H, Smirnova L, Brandt C, Pohl EE, Nitsch R, Wulczyn FG (2008) A feedback loop comprising lin-28 and let-7 controls pre-let-7 maturation during neural stem-cell commitment. Nat Cell Biol 10:987–993. 10.1038/ncb1759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M, Hirata H, Ohtsuka T, Bessho Y, Kageyama R (2003) The basic helix-loop-helix genes Hesr1/Hey1 and Hesr2/Hey2 regulate maintenance of neural precursor cells in the brain. J Biol Chem 278:44808–44815. 10.1074/jbc.M300448200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherpa T, Fimbel SM, Mallory DE, Maaswinkel H, Spritzer SD, Sand JA, Li L, Hyde DR, Stenkamp DL (2008) Ganglion cell regeneration following whole-retina destruction in zebrafish. Dev Neurobiol 68:166–181. 10.1002/dneu.20568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifuentes CJ, Kim JW, Swaroop A, Raymond PA (2016) Rapid, dynamic activation of Müller glial stem cell responses in zebrafish. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 57:5148–5160. 10.1167/iovs.16-19973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas JL, Ranski AH, Morgan GW, Thummel R (2016) Reactive gliosis in the adult zebrafish retina. Exp Eye Res 143:98–109. 10.1016/j.exer.2015.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thummel R, Enright JM, Kassen SC, Montgomery JE, Bailey TJ, Hyde DR (2010) Pax6a and Pax6b are required at different points in neuronal progenitor cell proliferation during zebrafish photoreceptor regeneration. Exp Eye Res 90:572–582. 10.1016/j.exer.2010.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueki Y, Wilken MS, Cox KE, Chipman L, Jorstad N, Sternhagen K, Simic M, Ullom K, Nakafuku M, Reh TA (2015) Transgenic expression of the proneural transcription factor Ascl1 in Müller glia stimulates retinal regeneration in young mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:13717–13722. 10.1073/pnas.1510595112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]