Abstract

Rett syndrome (RTT) is a neurological disorder caused by mutations in the X-linked gene methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2), a ubiquitously expressed transcriptional regulator. Despite remarkable scientific progress since its discovery, the mechanism by which MECP2 mutations cause RTT symptoms is largely unknown. Consequently, treatment options for patients are currently limited and centred on symptom relief. Thought to be an entirely neurological disorder, RTT research has focused on the role of MECP2 in the central nervous system. However, the variety of phenotypes identified in Mecp2 mutant mouse models and RTT patients implicate important roles for MeCP2 in peripheral systems. Here, we review the history of RTT, highlighting breakthroughs in the field that have led us to present day. We explore the current evidence supporting metabolic dysfunction as a component of RTT, presenting recent studies that have revealed perturbed lipid metabolism in the brain and peripheral tissues of mouse models and patients. Such findings may have an impact on the quality of life of RTT patients as both dietary and drug intervention can alter lipid metabolism. Ultimately, we conclude that a thorough knowledge of MeCP2's varied functional targets in the brain and body will be required to treat this complex syndrome.

Keywords: Rett syndrome, methyl-CpG-binding protein 2, histone deacetylase, nuclear corepressor, metabolism

1. Rett syndrome: clinical features and stages

Rett syndrome (RTT, OMIM #312750) was first described by Andreas Rett, an Austrian paediatric neurologist, after observing two female patients with identical hand-wringing stereotypies in his clinic waiting room. Upon examination, he found that both patients had the same history: normal early development, followed by a period of regression and loss of purposeful hand movements. Intrigued, Dr Rett documented other female patients in his clinic with similar symptoms. Believing the symptoms to be consistent with a metabolic disorder, he called it ‘cerebroatrophic hyperammonaemia’ in a 1966 German publication [1]. However, the disorder did not gain general acceptance among the medical community until its description in English publications 17 years later [2]. RTT is now well known as a progressive neurological disorder that primarily affects girls, occurring in 1 : 10 000–15 000 live female births [3].

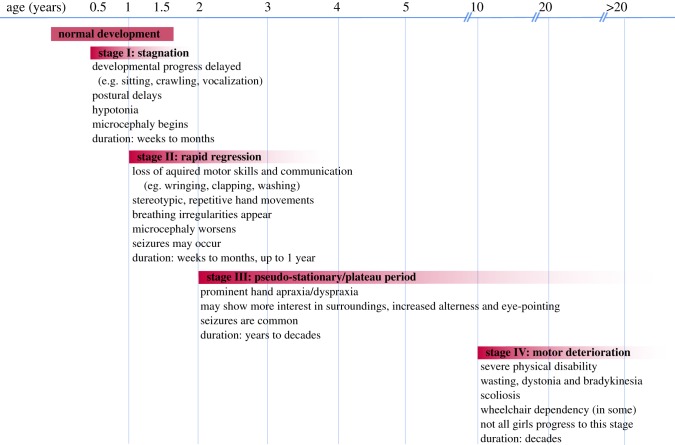

The clinical diagnosis of RTT is based on a battery of co-existing and well-defined inclusive and exclusive criteria (summarized in [4–6]). Following a period of normal neurological and physical development during the first 6–18 months of life, the first features of RTT begin to manifest in early childhood and appear progressively over several stages (figure 1): stagnation (age 6–18 months), rapid regression (age 1–4 years), pseudostationary (age 2–potentially life) and late motor deterioration (age 10–life). Characteristic symptoms of RTT include loss of acquired speech and motor skills, repetitive hand movements, breathing irregularities and seizures. RTT patients may also suffer from sporadic episodes of gastrointestinal problems, hypoplasia, early-onset osteoporosis, bruxism and screaming spells [4]. Despite these impairments, RTT patients are well integrated into their families and enjoy personal contact [7]. The development of new augmentative communication technologies has allowed otherwise non-verbal RTT patients to engage with others and express themselves [8].

Figure 1.

Timeline of stages and symptom onset in RTT patients. Rett syndrome (RTT) is divided into four progressive stages. Patients display seemingly normal early development. Between 6 and 18 months of age, patients experience a period of developmental stagnation (Stage I) and no longer meet their mental, cognitive or motor milestones. Head circumference growth slows and this period lasts for weeks to months. Stage II is defined by rapid developmental regression in which acquired purposeful hand movements and verbal skills are lost. Microcephaly worsens and breathing irregularities and/or seizures arise. Stage III is a pseudo-stationary plateau period in which patients may show mild recovery in cognitive interests, but purposeful hand and body movements remain severely diminished. Stage IV is defined by motor deterioration and may last decades. Many patients are wheelchair and/or gastrostomy-tube dependent. However, not all girls progress to this severe stage.

Many children diagnosed with RTT have reduced brain volume compared with healthy individuals, consistent with a smaller head circumference [9,10]. Reduced brain volume is largely due to small neuronal body size and a denser packing of cells, particularly in layers III and V of the cerebral cortex, thalamus, substantia nigra, basal ganglia, amygdala, cerebellum and hippocampus [11]. Patients also have reduced dendritic arborization, indicative of a delay in neuronal maturation [12]. Furthermore, hypopigmentation of the substantia nigra suggests a dysfunction of dopaminergic neurons [9]. RTT patients show evidence of dysregulated neurotransmitters, neuromodulators and transporters, indicating an important role in synaptic function [13,14].

Metabolic complications are also common in RTT. A number of patients present with dyslipidaemia [15,16], elevated plasma leptin and adiponectin [17,18], elevated ammonia [1] and inflammation of the gallbladder, an organ which stores bile for fat digestion [19]. Changes in brain carbohydrate metabolism [20] and neurometabolites associated with cell integrity and membrane turnover [21,22] have also been reported. Additionally, energy-producing mitochondria have abnormal structure in patient cells [23–26]. Consistently, altered electron transport chain complex function [27], increased oxidative stress [28–30], and elevated levels of lactate and pyruvate in blood and cerebrospinal fluid [20,27] have been observed in RTT patients (reviewed in [31]).

Treatment for RTT patients is currently limited to symptom control. With adequate attention to orthopaedic complications, seizure control and nutrition, women with RTT may survive into middle age and older. However, patients have a sudden and unexpected death rate of 26%, much higher than healthy individuals of a similar age, and typically die due to respiratory infection, cardiac instability and respiratory failure [32–34].

2. Mutations in MECP2 cause Rett syndrome

Familial cases were instrumental in determining the genetic cause of typical RTT. Multipoint linkage analysis of a Brazilian RTT family with three affected and three unaffected daughters narrowed the location of the gene to Xq28 [35]. Following this breakthrough in 1999, Amir et al. [36] systematically analysed nearly 100 candidate genes located in the Xq28 region for mutations in RTT patients. By screening genomic DNA from sporadic and familial RTT patients, the group identified damaging missense, frameshift and nonsense mutations in the coding region of the gene methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) in seven patients. It is now well established that mutations in MECP2 account for 95% of typical RTT cases and commonly occur de novo [36–38]. RTT patients are heterozygous for MECP2 mutation, carrying one normal and one mutated copy of MECP2. When a child presents with RTT-like symptoms, but does not fulfil all the diagnostic criteria for RTT, they may be diagnosed with atypical RTT, symptoms of which deviate in age of onset, sequence of clinical profile and/or severity (table 1) [39–49]. Many atypical cases are associated with mutations in X-linked cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 (CDKL5; OMIM #300203) or Forkhead box G1 (FOXG1; OMIM #164874), but some remain undefined [39–49]. Mutations in MECP2 have also been associated with intellectual disability, autism and lupus erythematosis [50,51].

Table 1.

Atypical Rett syndrome variants. These variants may be milder or more severe than classical RTT symptoms.

| type | description |

|---|---|

| severe atypical RTT variants | |

| early-onset seizure type | — can be caused by mutation in X-linked cyclin-dependent kinase-like five gene (CDKL5; OMIM #300203) — seizures in the first months of life — develop RTT symptoms |

| congenital variant | — can be caused by mutation in the Forkhead box G1 (FOXG1; OMIM #164874) gene located on chromosome 14 — born with congenital microcephaly and intellectual disability — lack of normal psychomotor development — develop RTT symptoms during first three months of life |

| milder atypical RTT variants | |

| late regression type | — develop RTT symptoms at a preschool age |

| preserved speech ‘Zapella’ type | — develop RTT symptoms but recover some verbal skills and can form phrases and sentences |

| ‘Forme fruste’ variant | — the most common atypical variant accounting for 80% of cases well-preserved motor skills and only subtle neurological abnormalities such as mild hand dyspraxia |

MeCP2 is an abundant nuclear protein that was originally identified in a screen for proteins with methyl-DNA-specific binding activity. It is ubiquitously expressed throughout all human tissues, but is particularly abundant within neurons [52,53]. In the central nervous system (CNS), MeCP2 is expressed at low levels prenatally, but progressively increases during neuronal maturation and synaptogenesis reaching its peak in mature, post-migratory neurons, suggesting a role for MeCP2 in maintaining neuronal maturation, activity and plasticity [54–57].

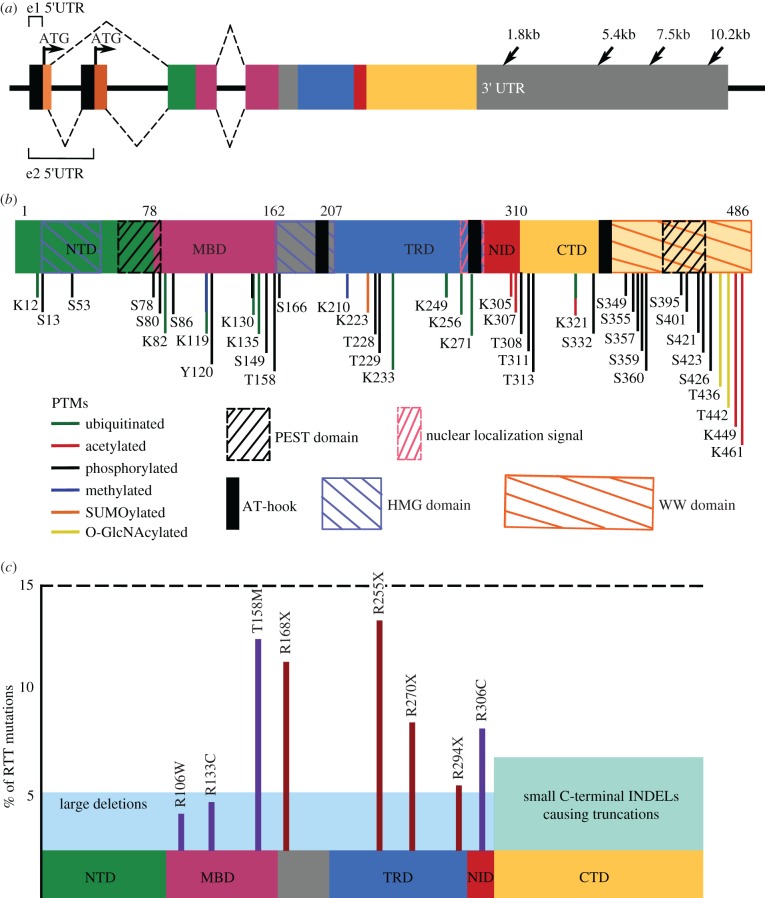

MECP2 is encoded by four exons which are expressed as the MeCP2_exon1 (e1) and the MeCP2_exon2 (e2) isoforms (figure 2a) [57–59]. MeCP2_e1 is 10 times more abundant than MeCP2_e2 in human and mouse brain and in mouse thymus and lung, whereas a 1 : 1 ratio is seen in mouse testis and liver [60,61], suggesting that e1 is the primary functional isoform in the brain. Exon 4 in both mouse and human contains an 8.5 kb 3′UTR, which is one of the longest known in the human genome, and features four polyadenylation (polyA) sites resulting in four differentially expressed transcripts (figure 2a) [62–64]. The 3′UTR may regulate downstream translation of MECP2's transcript by controlling mRNA degradation and stability, nucleocytoplasmic transport, mRNA localization and modulation of translation [65]. The alternate MECP2 transcripts show quantitative differences in expression in different tissues, in different stages of mouse embryonic development and in human post-natal brain development [62].

Figure 2.

Mutations in the multifunctional protein MeCP2 cause RTT. Coloured boxes indicate different encoded functional domains: light orange, N-terminus of MeCP2_e1; dark orange, N-terminus of MeCP2_e2; green, N-terminal domain (NTD) which has identical amino acid sequences between the two isoforms; pink, methyl-binding domain (MBD); blue, transcriptional repression domain (TRD); red, nuclear coreceptor co-repressor (NCoR) interaction domain (NID); yellow, C-terminal domain (CTD). (a) The four exons in the MECP2 gene. Arrows in exons 1 and 2 indicate the ‘ATG’ start codons for MeCP2_e1 or MeCP2_e2, respectively. Arrows in the 3′ UTR indicate multiple polyA sites resulting in different-length transcripts. Dashed lines on the top indicate the splicing pattern of MeCP2_e1 and dashed lines on the bottom indicate the splicing pattern of MeCP2_e2. (b) Functional domains and post-translational modifications (PTMs) of MeCP2. Coordinates are in relation to isoform MeCP2_e2. MeCP2 contains two PEST domains (black slashed boxes), two HMG domains (blue slashed boxes), three AT-hook domains (black solid boxes), one functional nuclear localization signal (NLS) (pink slashed box) and one WW domain (orange slashed box). PTMs are scattered throughout the protein and regulate interactions with MeCP2 binding partners. (c) Common damaging MECP2 mutations. Schematic of MeCP2 with functional domains. y-axis represents percentage of RTT patients with indicated mutation. Missense mutations are in purple and nonsense mutations are in red. Combined, these point mutations make up approximately 70% of all RTT-causing mutations.

MeCP2 consists of four primary functional domains (figure 2b). The binding specificity of MeCP2 is dependent on the presence of methylated DNA and its methyl-binding domain (MBD) located at amino acids 78–162 [53,66]. MeCP2 is different from other methyl-DNA binding proteins because of its ability to interact with a single, symmetrical methylated CpG (mCpG) site [53,66]. However, recent work by Lagger et al. revealed that MeCP2 also has a high binding affinity for methylated and hydroxymethylated CAC (mCAC and hmCAC, respectively) in neurons, demonstrating that both methylated dinucleotides and trinucleotides can recruit MeCP2 to DNA for transcriptional regulation [67]. A transcriptional repressor domain (TRD) occurs in amino acids 207–310, and contains the NCoR-interaction domain (NID), which facilitates binding of MeCP2 to the NCoR1/SMRT co-repressor complex [68–71]. The C-terminal domain (CTD) also shows DNA-binding ability, suggesting the presence of a chromatin-interacting domain in the vicinity of the 5′ region of the CTD [72].

CpG methylation is minimal in invertebrate genomes (10–40%), but very high in vertebrate genomes (60–90%) [73,74]. Methylated DNA sites recruit methyl-DNA-binding proteins like MeCP2, which attract transcriptional regulatory complexes [75]. Consistently, MeCP2 represses transcription in a gene-specific manner, interacting with the co-repressor complexes mSIN3A and NCoR1/SMRT [70,76]. However, MeCP2 may also facilitate transcriptional activation [77], chromatin compaction [78,79] and mRNA splicing [80,81], while also interacting with a host of other regulatory proteins involved in a variety of molecular pathways [81–84].

Despite having well-defined functional domains, MeCP2 classifies as an intrinsically disordered protein (IDP) and acquires tertiary structure upon interaction with other protein partners or nucleic acids [85]. Disordered structure makes IDPs notoriously promiscuous binding partners [86]. As such, post-translational modifications (PTMs) add an additional layer of regulation to ensure MeCP2 binding to appropriate partners. Accordingly, MeCP2 undergoes many PTMs including acetylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination and SUMOylation (figure 2b; reviewed in [87,88]), which strongly regulate interactions. Altogether, multiple studies suggest that genes can be activated or repressed by MeCP2, depending upon the cellular context [77,89,90], suggesting that MeCP2 may be defined as a transcriptional modulator.

3. Phenotype variation among people with MECP2 mutations

According to the Human Gene Mutation database, 555 RTT-causing mutations have been identified in MECP2 [91]. De novo mutations account for 99.5% of the mutations in MECP2, of which approximately 70% are C > T transitions, which typically arise due to hypermutability at mCpG dinucleotides within the MECP2 locus [48]. Unlike the X chromosome in oocytes, the X chromosome in sperm is hypermethylated. It has been speculated that spontaneous deamination of methylated cytosine residues may result in a transition to a thymine, increasing the potential for deleterious mutations at hypermethylated CpG sites [92,93]. As such, most de novo MECP2 mutations originate from the paternally inherited X chromosome [94].

The wide spectrum of MECP2 mutations includes point mutations, insertions, duplications, small or large deletions, or whole MECP2 gene deletions. Despite this, only eight missense and nonsense mutations (R106 W, R133C, T158M, R168X, R255X, R270X, R294X and R306C) account for approximately 70% of all mutations in RTT (figure 2c). C-terminal deletions account for another approximately 8%, and large deletions constitute approximately 5% [38]. Mutation types tend to cluster: missense mutations frequently occur in the MBD, while nonsense mutations generally occur downstream of the MBD [38]. Frameshift mutations resulting from small deletions usually occur in the C-terminus (figure 2c) [48]. The location of the mutation reduces specific aspects of MeCP2 function [95]. For example, mutations located in the MBD reduce the DNA-binding ability of MeCP2.

In early studies, Hagberg et al. [2] noted that the severity of motor impairment in classic female RTT patients ranged from wheelchair bound before age five to retaining the ability to walk with a Parkinsonian-like gait. Given the wide variety of mutation types and phenotype severity, genotype–phenotype studies have correlated mutation status with clinical features of RTT patients [38]. Early truncating mutations in the MECP2 gene such as R168X, R255X and R270X, and large INDELs, cause the most severe phenotype. Missense mutations such as R133C and R306C, late truncating mutations such as those in R294X, and others in the 3′ end, which keep the MBD and most of the TRD intact, are the mildest [38,96]. Therefore, MECP2 mutation status is a strong predictor of disease severity, but phenotype variation commonly occurs between individuals with the same MECP2 mutation and is attributed to differences in X chromosome inactivation (XCI) [97].

Female heterozygous RTT patients are mosaic, allowing some cells to express the mutant MECP2, while the others express the wild-type allele. XCI can be skewed preferentially so the mutant X chromosome is more or less expressed than the wild type, resulting in either a relatively more severe or milder presentation of RTT, respectively [98,99]. The mother of the children in the original Brazilian family presented no symptoms because her X-inactivation footprint skewed 95% of expression from the non-mutated chromosome [35]. Interestingly, several patients with the same mutation may exhibit a broad spectrum of clinical severity despite similar patterns of XCI in peripheral blood, potentially due to second gene mutations (modifiers) that alleviate or enhance the phenotypic outcome of MECP2 mutation [100].

As an X-linked disorder, RTT was considered to be lethal in males. However, males with clinical features resembling classical RTT were reported even before the discovery of the causal gene. In 1999, Wan et al. [37] described the first mutation in MECP2 in a male patient who died at one year of age from congenital neonatal encephalopathy. This discovery prompted the inclusion of boys in screening for MECP2 mutations, allowing them to be classified into four categories: severe neonatal encephalopathy and infantile death, typical RTT, less severe neuropsychiatric phenotypes or MECP2 duplication syndrome (table 2) [101–108].

Table 2.

Males with MECP2 mutations fall into four categories.

| category | MECP2 profile | features |

|---|---|---|

| severe neonatal encephalopathy and infantile death | MECP2 mutation passed on by mildly symptomatic or asymptomatic mother | — spontaneously miscarried — if born, develop neonatal encephalopathy, respiratory arrest and seizures, death within 2 years |

| classical RTT | have at least partial Klinefelter's syndrome (XXY karyotype) or other somatic mosaicism | — symptoms similar to female RTT patients |

| less severe neuropsychiatric symptoms | MECP2 mutations are less severe than those in female RTT patients | — symptoms are broad and overlap with features of Angelman syndrome (intellectual disability and motor abnormalities) |

| MECP2 duplication syndrome | gain of MECP2 dosage | — hypotonia, severe intellectual disability, recurrent lung infections, absent or limited speech and walking, seizures, motor spasticity and muscle stiffness — 50% die before age 25 |

4. Animal models inform MECP2 function

MECP2 appears across vertebrate evolution with strong conservation in its functional domains. Drosophila do not possess an orthologue to human MECP2, perhaps because the invertebrate genome is sparsely methylated [109]. In 2013, Pietri et al. isolated the first null mecp2Q63*/Q63* zebrafish model, which does not recapitulate features of the human disorder [110,111]. Instead, the fish are viable and reproduce normally, but display minor motor abnormalities and a shortened lifespan, possibly due to immune deficiencies [112]. In 2017, Chen et al. [113] published the first analysis of MECP2-mutant cynomolgus monkeys, which exhibit decreased movement, social withdrawal, increased stereotypical behaviour and sleep abnormalities—symptoms common in RTT patients [113]. Overall, the monkeys exhibit CNS and transcriptome changes that are consistent with the human, in spite of being genetically heterogeneous [113]. Therefore, simian models may serve as a robust, albeit expensive, system to study sophisticated features of RTT in the future.

Mecp2 mutant rodents recapitulate many hallmark symptoms of RTT and are the most widely accepted tool to study the disorder. An engineered null rat model of RTT (Mecp2ZFN) shows phenotypic and transcriptomic similarities to mouse models [114–116]. Although rats would have advantages for physiologic and preclinical testing, they are not used widely, perhaps due to their cost and the lack of genetic tools. Instead, two null mouse alleles are the primary models for Rett syndrome (table 3). The Bird laboratory developed a Mecp2 mutant mouse model by engineering loxP sites flanking Mecp2 exons 3 and 4 to create a ‘floxed’ conditional line [117]. This conditional-ready allele, called Mecp2tm1Bird, is hypomorphic, resulting in mild RTT-like symptoms due to a 50% reduction in MeCP2 expression [118,119]. A null mouse line lacking any protein product was created by crossing with a germline-deleting Cre driver (Mecp2tm1.1Bird/Y) [117]. Simultaneously, the Jaenisch lab designed a Mecp2 mutant mouse by engineering loxP sites flanking exon 3, Mecp2tm1.1Jae [120]. A smaller Mecp2 transcript and protein fragments are present in mutant brain; however, these mice show phenotypes similar to the null Bird allele.

Table 3.

Mecp2 mutant mouse models. The Mecp2tm1.1Bird and Mecp2tm1.1Jae alleles are the most commonly studied. Point mutation alleles are designed to mimic human RTT-causing mutations. Many conditional deletions have been created, but are not summarized here.

| allele type | allele description | phenotypes | death (males) | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| null alleles | ||||

| Mecp2tm1.1Bird | deletion of exon 3–4 | stiff gait, reduced movement, hindlimb clasp, tremors, dishevelled fur, B6 underweight, 129 overweight | 7–10 weeks | [79] |

| Mecp2tm1.1Jae | deletion of exon 3a | abnormal gait, hypoactive, tremors, mixed reports on weight | 10 weeks | [82] |

| point mutation alleles | ||||

| Mecp2tm1Hzo | R308X; truncation | ataxia, tremors, dishevelled fur | >1 year | [89] |

| Mecp2tm1.1Jtc | R168X; truncation | hypoactive, hindlimb atrophy and clasping, breathing irregularities | 12–14 weeks | [90,91] |

| Mecp2tm2.1Jae | S80A; missense | motor defects, slightly overweight | >1 year | [48] |

| Mecp2tm1Vnar | A140 V; missense | asymptomatic | >1 year | [92] |

| Mecp2tm1.1Meg | S421A; missense | asymptomatic | >1 year | [93] |

| Mecp2tm1.1Joez | T158A; missense | abnormal gait, hypoactive, hindlimb clasp, reduced weight | 16 weeks | [94] |

| Mecp2tm1.1Mitoh | deletion of MeCP2 exon 2 | asymptomatic but have placental defects | >1 year | [95] |

| Mecp2tm5.1Bird | R306C; missense | poor mobility, hindlimb clasping, tremors | 18–25 weeks | [44] |

| Mecp2tm3Meg | T308A; missense | poor mobility, hindlimb clasping | >16 weeks | [45] |

| Mecp2tm1.1Dhy | deletion of MeCP2 exon 1 | hypoactive, hindlimb clasping, excessive grooming | 7–31 weeks | [96] |

| Mecp2tm4.1Bird | T158M; missense | poor mobility, hindlimb clasping, tremors | 13 weeks | [97] |

| Mecp2tm6.1 Bird | R133C; missense | poor mobility, hindlimb clasping, tremors | 42 weeks | [97] |

| Mecp2tm1.1Irsf | R255X; nonsense | breathing irregularities, heart defects | 8–10 weeks | [98] |

| Mecp2tm3.1Joez | T158M; missense | abnormal gait, poor mobility, breathing irregularities, underweight | 13 weeks | [99] |

| Mecp2tm4.1Joez | R106 W; missense | hypoactive, hindlimb clasping, underweight | 10 weeks | [100] |

| conditional alleles | ||||

| Mecp2tm1Bird | floxed exons 3–4; hypomorphic |

mild phenotype similar to Mecp2tm1.1Bird with delayed onset | as wild-type | [79] |

| Mecp2tm1Jae | floxed exon 3 | no phenotype | as wild-type | [82] |

| Mecp2tm2Bird | floxed stop upstream exon 3 | identical to Mecp2tm1.1Bird | 10 weeks | [106] |

aSome protein product retained.

Although RTT predominantly affects girls, the vast majority of published mouse studies take place in hemizygous Mecp2 mutant male mice, because they present with a more consistent phenotype early in life. While female Mecp2 mutant mice are more clinically relevant, random XCI in rodent females causes skewing of gene expression, resulting in large variations in phenotype presentation, making it difficult to separate which phenotypes arise through cell autonomous versus non-autonomous pathways [121]. The most commonly used male mouse models, Mecp2tm1.1Bird and Mecp2tm1.1Jae, consistently display overt phenotypes at four to six weeks of age, and die between 8 and 12 weeks of age [117,120]. Though Mecp2 null mice are asymptomatic prior to four weeks of age, there are subtle but consistent defects in transcription, ionotropic receptor signalling, and neuronal responsiveness during late embryogenesis and the perinatal period [122–124]. At four weeks of age, null mice begin to develop uncoordinated gait, hypoactivity, tremors, hindlimb clasping reminiscent of the hand stereotypies seen in RTT patients, and irregular breathing. These phenotypes progress in severity until death. The soma and nuclei of Mecp2 mutant neurons in the hippocampus, cerebral cortex and cerebellum are smaller and more densely packed than in wild-type littermates, probably giving rise to a smaller brain [120].

Curiously, body weight in Mecp2 null mice differs depending on genetic background; male Mecp2tm1.1Bird/Y mice on a C57BL/6J background are substantially underweight by four weeks of age compared with wild-type littermates. On a 129S6/SvEvTac strain, males show a reverse effect: Mecp2tm1.1Bird/Y mice are the same weight as wild-type littermates until eight weeks of age, when they become significantly heavier than siblings [117]. Lastly, Mecp2tm1.1Bird/Y mice on a CD1 background weigh slightly less than wild type early in life, but reach a normal weight by six to seven weeks of age [125].

Heterozygous female mice also show no symptoms initially, but become hypoactive and start to hindlimb clasp at three months. By nine months of age, approximately 50% of heterozygous females develop the same phenotypes as their null counterparts, but some females remain asymptomatic at 1 year. Therefore, females have a lifespan that allows for reproduction, suggesting that the heterozygous condition can exhibit long-term stability, as seen in RTT [117]. Interestingly, heterozygous female mice on all genetic backgrounds, as well as female rats, become significantly overweight as they age [115,117,125], although humans with RTT have a wide range in body mass index [15].

In addition to deletion mouse models, several alleles have been engineered to recapitulate clinically relevant and common MECP2 mutations in human patients. Mice with these alleles tend to display milder and later onset neurological phenotypes compared with the Mecp2tm1.1Bird null allele, and most do not recapitulate the entire disease phenotype (summarized in table 3) [70,71,126–138]. In an effort to distinguish the cause of specific phenotypes, Mecp2 has also been conditionally deleted from different cell types and tissues [139–142]. A number of conditional deletions in different subsets of neurons highlight the essential role of MeCP2 in neuronal function, yet their milder presentation suggests additional roles outside the CNS (reviewed in [143]).

RTT patients show abnormal neuronal morphology, but not neuronal death, giving legitimacy to the possibility that defective MeCP2-deficient cells can recover [144]. In a landmark study, Guy et al. achieved symptom reversal in Mecp2 mutant mice following the onset of motor dysfunction and neurological deficits. The Mecp2tm2Bird ‘FloxedStop’ allele, in which a loxP-STOP-Neo-loxP cassette was inserted into the intron upstream of endogenous Mecp2 exon 3, was crossed with mice carrying a Cre recombinase fused to the oestrogen receptor (OR). Injection of tamoxifen (TM) caused Cre-ER to translocate to the nucleus and delete the FloxedStop cassette to reactivate the Mecp2 gene [145]. FloxedStop/Y male mice behaved like Mecp2tm1.1Bird/Y mice, developed RTT-like symptoms between four and six weeks of age, and survived for approximately 10 weeks on average. TM injections in mice with advanced neurological symptoms and breathing abnormalities restored Mecp2 expression to 80% of wild-type levels. Remarkably, restoration of MeCP2 expression reversed symptoms: neurological assessments and overall health improved and 80% of TM-treated animals survived beyond 30 weeks of age (end of study). Similarly, symptomatic FloxedStop/+ heterozygous female mice showed significant symptom improvement upon TM injection, including a reduction in body weight [145]. This pivotal finding showed that developmental absence of MeCP2 does not irreversibly damage neurons, instilling hope that symptom reversal is possible in RTT patients.

5. MeCP2 modulates transcription by bridging DNA with regulatory complexes

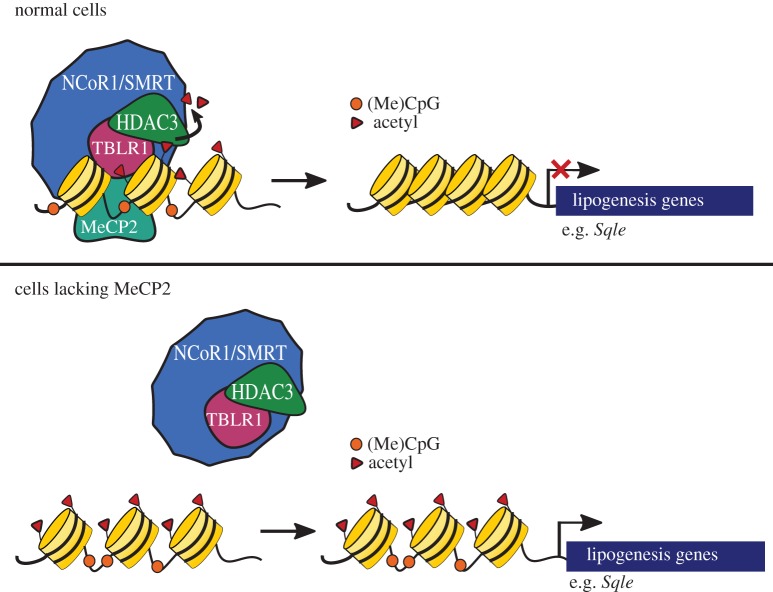

In 2001, Kokura et al. [83] first demonstrated that MeCP2 binds to the NCoR1/SMRT co-repressor complex. NCoR1 and SMRT are highly homologous proteins that are recruited to chromatin to repress transcription by acting as a scaffold protein for other nuclear receptors, DNA-binding proteins and histone deacetylases [146]. One role of the NCoR1/SMRT complex is to recruit histone deacetylase 3 (HDAC3) to DNA, which removes histone acetyl marks, resulting in a closed chromatin state [147,148]. Other members of this complex include G protein pathway suppressor 2 (GPS2), transducin beta-like 1 (TBL1) and transducin beta-like 1 related (TBLR1) [149]. The interaction of MeCP2 with the NCoR1/SMRT complex was re-examined over a decade later when Lyst et al. [70] sought to identify binding partners of MeCP2. MeCP2 protein was purified from the brains of reporter mice with an enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP) inserted in the 3′ UTR of the Mecp2 gene (Mecp2tm3.1Bird) and mass spectrometry was used to identify associated proteins. Remarkably, five of the seven MeCP2 protein interactors identified were subunits of the NCoR1/SMRT co-repressor complex [70]. Furthermore, this group found that the interaction between MeCP2 and the NCoR1/SMRT complex was facilitated by the NCoR1/SMRT interaction domain (NID) located at MeCP2 amino acids 285–309 [70,71]. MeCP2 binds to complex members TBL1 and TBLR1 at these residues via a WD40 domain, unlike other NCoR1/SMRT recruiters which interact with the NCoR1/SMRT scaffold proteins directly [150]. These findings have led to a model wherein MeCP2 serves as a bridge between methylated DNA and the corepressor complex, anchoring the NCoR1/SMRT complex to DNA via its NID and MBD, respectively. It is hypothesized that disruption of this bridge leads to histone hyperacetylation and an open chromatin state, thereby increasing the transcription of target genes (figure 3). Even so, transcriptional profiling studies using whole brain Mecp2/Y mice have not revealed dramatic gene expression changes [151,152], perhaps because the highly heterogeneous nature of the brain masks significant perturbations in subpopulations of cells.

Figure 3.

MeCP2 anchors the NCoR/SMRT to methylated DNA. In healthy cells, MeCP2 binds methylated CpG dinucleotides (orange circles) and recruits the NCoR1/SMRT-HDAC3 co-repressor complex to regulatory sites surrounding the target loci. HDAC3 removes acetylation marks from surrounding histones to compact chromatin and prevent transcription of target genes. In Mecp2 mutant cells, the NCOR1/SMRT-HDAC3 complex cannot bind to methylated DNA resulting in an open chromatin state and increased transcription of genes. Known target genes of the complex in the liver include Sqle and other lipogenesis enzymes. Targets in the brain remain unknown.

RTT-causing missense mutations cluster in the MBD and NID, highlighting the importance of these two regions of MECP2 in RTT pathology [153]. Within the NID is a mutational hotspot of MeCP2 between amino acids 302 and 306 [70,154]. R306C is one of the more common RTT mutations, and this allele was modelled in mice to determine the biological relevance of the NCoR1 corepressor complex in RTT (table 3) [68]. By six weeks of age, male Mecp2R306C mice develop tremors, hypoactivity, hindlimb clasping and motor activity defects. Fifty per cent of Mecp2R306 mice fail to survive past 18-weeks of age and all die by 25 weeks [70]. The R306C mutant MeCP2 has an intact MBD, which binds to methylated heterochromatin. However, the mutation disables the NID, preventing MeCP2 from binding TBL1 or TBLR1, and thus the complex that contains NCoR1 and HDAC3, which disrupts MeCP2-mediated transcriptional repression. This suggests that the interruption of the MeCP2-NCoR1/SMRT complex interaction alone is capable of causing RTT-like phenotypes.

To test the primary role of the MeCP2-NCoR/SMRT1 interaction, the effect of a radically truncated MeCP2 protein was examined for symptom reversal in mice [155]. Mice were generated expressing a MeCP2 protein consisting of only the MBD, NID and short linker regions, while all other amino acid sequences of MeCP2 were removed. Remarkably, mice expressing this truncated protein develop only mild RTT-like symptoms and have a normal life span. Additionally, genetic re-activation or virus-mediated delivery of this minimal MeCP2 protein prevents or ameliorates symptoms in Mecp2-deficient pre-symptomatic or post-symptomatic mice, respectively. This suggests that a very important role of MeCP2 is to link DNA to the NCoR1/SMRT complex.

6. A mouse mutagenesis screen links MeCP2 to lipid metabolism

While Mecp2 mutant mice are an excellent model for RTT, elimination of MeCP2 affects the expression of a profound number of pathways in the CNS, making it difficult to pinpoint which ones play a key role in pathology [77,89,90]. For this reason, Buchovecky et al. [156] employed an unbiased forward genetic suppressor screen in Mecp2 null mice to identify mutations that alleviate RTT symptoms, which could be exploited as potential treatment targets. Genetic screening is a powerful tool to detect pathways involved in disease aetiology independent of a priori assumptions. Curiously, a dominant nonsense mutation was found in squalene epoxidase (Sqle), a monooxygenase and rate-limiting cholesterol biosynthesis enzyme, which requires an electron donor from mitochondria for its function [157]. This mutation in Sqle improved RTT-like motor phenotypes, overall health and lifespan in Mecp2 null male mice [156]. This sparked the question: is cholesterol metabolism perturbed in Mecp2 mutant mice?

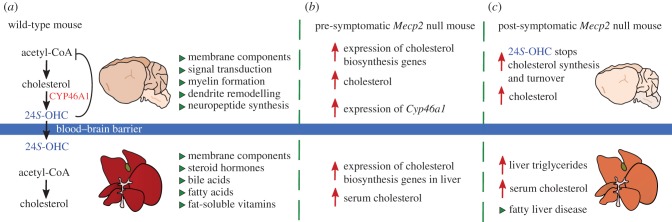

Cholesterol is a fundamental component of all cells [158,159]. While the liver is the primary manufacturer of cholesterol for the body, cholesterol is also a major component of the brain, where it functions in membrane trafficking, signal transduction, myelin formation, dendrite remodelling, neuropeptide formation and synaptogenesis [160]. Importantly, cholesterol cannot cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB), so any cholesterol that the brain requires must be synthesized in situ [161]. Therefore, the brain has complex and tightly regulated cholesterol synthesis pathways with multiple axes of self-regulation; too much or too little cholesterol is detrimental, and imparts negative consequences on cognition, memory and motor skills. To maintain homeostasis, cholesterol can be converted into the oxysterol 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol (24S-OHC) by the neuron-specific enzyme CYP46A1 (figure 4a) [162]. Oxysterols can pass lipophilic membranes more easily than cholesterol, allowing for one-way egress across the BBB and into the body [163].

Figure 4.

Cholesterol metabolism is perturbed in Mecp2 mutant mice. (a) In the wild-type mouse, the brain produces cholesterol in situ as cholesterol cannot pass the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Acetyl-CoA enters the cholesterol biosynthesis pathway to make cholesterol which has many essential functions (green triangles). The enzyme CYP46A1 converts excess cholesterol into 24S-hydroxycholesterol (24S-OHC) for one-way egress across the BBB. The liver participates in cholesterol biosynthesis to provide cholesterol to other tissues in the body. (b) In pre-symptomatic Mecp2 null mice (3–4 weeks old), increased expression of cholesterol biosynthesis genes in the brain leads to elevated brain cholesterol levels. Consequently, the expression of Cyp46a1 is increased, indicating a heightened need for cholesterol turnover. Outside of the central nervous system, serum cholesterol is elevated, and expression of cholesterol biosynthesis genes is elevated in the liver. (c) In symptomatic Mecp2 null mice (8–10 weeks old), the brain is smaller due to lack of Mecp2. Cholesterol biosynthesis decreases drastically in the brain, likely due to feedback from elevated 24S-OHC. Owing to decreased synthesis, brain cholesterol remains high, but not as high as at younger ages (smaller red arrow). Serum cholesterol and/or triglycerides may also be elevated, depending upon genetic background. Triglycerides accumulate in the liver, and fatty liver disease develops, as indicated by pale liver.

Abnormalities in brain lipid homeostasis are associated with developmental disorders and diseases of ageing. Neimann–Pick type C patients accumulate cholesterol in the brain and peripheral tissues, and present with symptoms similar to RTT such as loss of acquired verbal skills and lack of motor coordination [164]. Patients with Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome develop microcephaly, cleft lip/palate, liver defects and autistic behaviours due to a deficiency in 7-dehydrocholesterol, allowing for the toxic build-up of cholesterol intermediates [165]. Furthermore, aberrant cholesterol homeostasis has been implicated in Fragile X syndrome [166], amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [167], Alzheimer's [168], Parkinson's [169] and Huntington's [170] diseases. However, lipid anomalies had never before been described in RTT and whether cholesterol played a primary role in the pathology of the disease was unknown.

Strikingly, Buchovecky et al. [156] found that cholesterol homeostasis is perturbed in the Mecp2 null mouse brain. Pre-symptomatically, Mecp2 null whole brain cholesterol is elevated, and Cyp46a1 expression is increased 38% over wild-type levels, indicating a heightened need for cholesterol turnover in neurons [156] (figure 4b). Post-symptomatically, the overproduction of cholesterol decreases sterol synthesis in Mecp2 null brains due to regulatory feedback [156,171] (figure 4c).

Notably, metabolic phenotypes differ in Mecp2 null mice across genetic backgrounds. While both 129.Mecp2tm1.1Bird mice and B6.Mecp2tm1.1Jae mice show decreased sterol synthesis in the brain, elevated cholesterol and triglycerides in the serum and liver are observed only in 129.Mecp2tm1.1Bird mice [156]. Additionally, CD1.Mecp2tm1.1Bird mice have an increase in serum triglycerides with no corresponding change in serum cholesterol [125]. The C57BL/6 J inbred strain and the 129/Sv substrains manage peripheral cholesterol metabolism differently, presumably due to differences in the transport of cholesterol breakdown products [172]. Together, these data suggest that perturbed brain cholesterol synthesis is a common feature of Mecp2 null mice; however, it is likely that genetic background contributes to the Mecp2 null peripheral metabolic phenotype.

These differential findings in mice suggested that peripheral lipid markers would not be elevated in all patients. Consistently, only a subset of RTT patients exhibit increased serum cholesterol and/or triglycerides [15,16,173]. Outside of the CNS, sterols are the precursors of steroid hormones, bile acids and vitamin D. Interestingly, some RTT patients have bone abnormalities, severe gastrointestinal problems and biliary tract disorders [174–176]. As perturbations in lipid homeostasis may influence both neurological and non-neurological RTT symptoms, the measurement of lipid parameters may serve as a non-invasive and inexpensive biomarker to identify RTT patients who may benefit from treatments that target lipid metabolism.

7. MeCP2 regulates lipid metabolism with NCoR1/SMRT-HDAC3

Notably, the NCoR1/SMRT corepressor complex is an important component in regulating the diurnal control of energy metabolism. During the fasting cycle, the NCoR1/SMRT-HDAC3 complex maximally occupies hepatocyte chromatin, repressing the expression of genes involved in lipid synthesis and sequestration. However, during the feeding cycle, it releases chromatin, allowing for expression of its targeted loci [177]. This binding oscillation governs the switch between lipid and glucose utilization in hepatocytes. Mice with a liver-specific deletion of Hdac3 display an increased expression of de novo lipogenesis enzymes due to a constitutively active transcriptional environment, resulting in fatty liver disease and elevated serum cholesterol [178,179]. Overall, the NCoR1/SMRT-HDAC3 complex orchestrates lipogenesis, and its disruption leads to perturbed lipid homeostasis. Therefore, it was expected that loss of MeCP2, the functional bridge between NCoR1/SMRT-HDAC3 and DNA, would lead to transcriptional dysregulation of lipogenesis and metabolic perturbations in mice. In support of this, Sqle, the suppressor of RTT-like phenotypes in mice, is a target of HDAC3, and its transcription increases approximately 170-fold in response to Hdac3 liver deletion [156,178].

Indeed, Kyle et al. [180] showed that Mecp2 mutant mice develop severe dyslipidaemia due to aberrant transcription of lipogenesis enzymes in the liver, because MeCP2 interacts with the NCoR1/SMRT-HDAC3 complex to repress lipogenic gene transcription. Loss of MeCP2 decreases HDAC3 binding to DNA, resulting in hyperacetylated histones, and increases transcription of numerous lipid-regulating genes. Interestingly, liver-specific deletion of Mecp2 (B6.Mecp2tm1Bird/Y;Alb-Cre) also results in an increase in lipogenic enzyme transcription [180]. Similar to Mecp2 null mice and a liver-specific deletion of Hdac3, these mice develop dyslipidaemia, fatty liver and metabolic disease. These results support a hepatocyte-autonomous role for Mecp2 in co-ordinating repression of enzymes of the cholesterol and triglyceride biosynthesis pathways and show that loss of Mecp2 from the liver is sufficient to cause metabolic disease in mice. Notably, background strain is unlikely to influence MeCP2's role in regulating liver lipid synthesis as both 129.Mecp2tm1.1Bird and B6.Mecp2tm1Bird/Y; Alb-Cre mice showed perturbed lipid metabolism.

8. Cholesterol-lowering statin drugs may be repurposed to treat RTT

Considering that cholesterol metabolism is perturbed in Mecp2 mice, it was possible that pharmacological treatment with cholesterol-lowering drugs (statins) would improve symptoms. The primary mechanism of action for statin drugs is to competitively inhibit 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase (HMGCR), a rate-limiting step in cholesterol biosynthesis [181], effectively reducing the endogenous production of cholesterol. Owing to the prominent role of cholesterol in cardiovascular disease, statins are medically prescribed to prevent atherosclerosis. However, statins are associated with other disease-improving side-effects, such as reducing inflammation [182,183], and negative side-effects, such as muscle weakness [184] and acute memory loss [185]. Owing to their relative safety, recent studies have explored how statin drugs can be repurposed to treat non-cardiovascular diseases including Fragile X syndrome and neurofibromatosis Type I [186,187].

Remarkably, treatment with either fluvastatin or lovastatin improves subjective health scores, motor performance (measured by rotarod and open field activity) and increases lifespan in 129.Mecp2tm1.1Bird male and female mutant mice when compared with control mice receiving a vehicle [156]. Lovastatin is the more lipophilic of these statins, increasing the likelihood of crossing the BBB and entering the brain. Even so, treatment with either statin improves cholesterol homeostasis in the brains of Mecp2 mutant mice, lowers serum cholesterol and ameliorates lipid accumulation in the liver. Interestingly, lovastatin does not have a strong therapeutic effect on B6.Mecp2tm1.1Bird male mice, supporting the idea that elevated peripheral lipids may be a biomarker for those patients who may respond to statin drugs [188]. Nevertheless, these findings support the idea that lipid metabolism, a pathway that has many opportunities for drug or dietary intervention, could be exploited for symptom improvement in a subset of RTT patients [156]. Importantly, these findings led to a phase 2 clinical trial for the pharmacological treatment of RTT with lovastatin (NCT02563860).

9. Implications for understanding and treating childhood neurological disorders

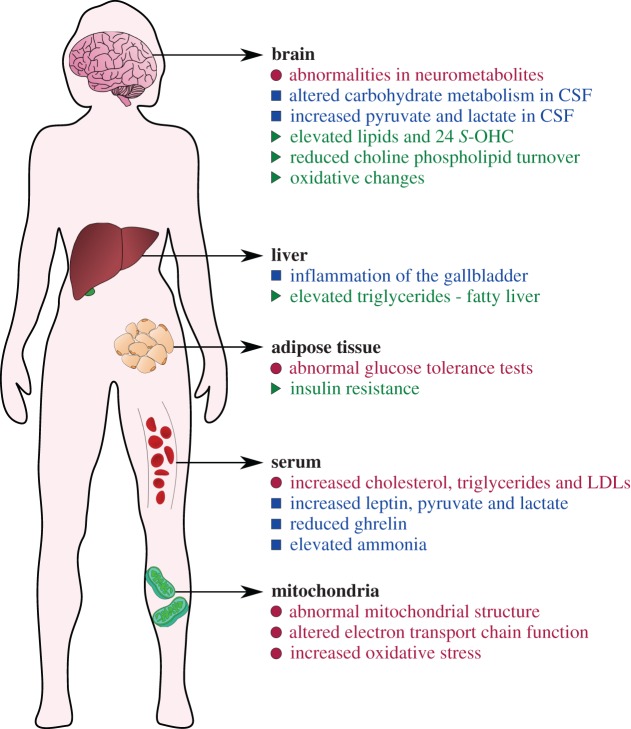

Rett syndrome remains a difficult disorder to understand and treat, largely because MeCP2 is central to the regulation of gene expression in many tissues and cell types. More than 60 years after the description of RTT as a metabolic disease of the nervous system, we have finally come to an understanding of some of the metabolic aspects of pathology (summarized in figure 5). Despite this, metabolic parameters vary greatly within the RTT patient population and among different mouse strains indicating that genetic variation may play a large role in the penetrance of metabolic symptoms.

Figure 5.

Metabolic components of Rett syndrome. Common metabolic disturbances observed in RTT patients (blue squares), Mecp2-mutant mouse models (green triangles) that may be a feature of human disease, or in both human and mouse (pink circles). Note that metabolic parameters may vary within the patient population or among different mouse strains: for example, hyperammonaemia was found in a subset of patients, but was dropped as a diagnostic criterion because it was not common. Such findings suggest that genetic variation may play a big role in the penetrance of all but key diagnostic features.

In neurons, MeCP2 serves as a bridge between the NCoR1/SMRT-HDAC3 complex and DNA to facilitate transcriptional repression, and mutations that affect MeCP2 binding to the complex cause RTT. While both Ncor1 and Hdac3 null mice die as embryos, a neuron-specific deletion of Hdac3 produces viable mice that gradually develop a phenotype very similar to that of Mecp2 null mice including abnormal motor coordination, reduced sociability and cognitive defects [189]. These data suggest that at least a subset of RTT-like phenotypes in Mecp2 mutant mice are caused by the loss of HDAC3 in neurons. Moreover, the role of the NCoR1/SMRT-HDAC3 in regulating lipogenesis in the Mecp2 mouse liver raises interesting questions about the role of this complex in regulating lipids in the brain. Biochemistry studies have largely failed to find definitive gene regulatory targets, in part, because MeCP2 binds DNA at levels rivalling histone octamers [190]. Moreover, the brain is a complex organ with many different cell types in various stages of activity, making whole brain studies difficult to interpret. It is likely that at certain times and in specific cells, MeCP2 is required to anchor the NCoR1/SMRT-HDAC3 complex to DNA, regulating lipid production in some cells in the brain as in the liver.

As cholesterol synthesis is a resource-expensive process, current data suggest that newborn neurons must produce cholesterol in a cell-autonomous manner, but as they mature they outsource production to astrocytes (reviewed in [160,191]). Interestingly, wild-type neurons have abnormal dendritic morphology when co-cultured with MeCP2-deficient astrocytes, yet MeCP2-deficient neurons have normal dendritic morphology when co-cultured with wild-type astrocytes [192]. Moreover, deletion of MeCP2 from glial cells induces a RTT-like phenotype, and re-introducing MeCP2 to astrocytes of Mecp2 null mice using GFAP-Cre improves symptoms and restores dendritic morphology [193,194]. These data could be explained by the hypothesis that at some point during development, cholesterol synthesis is reduced in a subset of neurons, and is provided instead by astrocytes; in the RTT brain, this downregulation does not occur, leading to lipid accumulation [160]. Certainly, this possibility may also explain the difference in timing of onset of symptoms in mice and humans, because the downregulation of cholesterol synthesis in neurons shortly precedes the onset of RTT-like symptoms in mice. New approaches provided by single-cell genomic technologies may provide definitive answers to this possibility.

Metabolic dysregulation in RTT and other diseases may impart substantial consequences on downstream systems. When one arm of metabolism is perturbed, it affects each connecting pathway, including glucose, lipid, amino acid, nitrogen and mitochondrial respiratory metabolism. Not surprisingly, both RTT patients and Mecp2 mutant mice have abnormal responses to glucose tolerance tests, and mutant mice are also insulin-resistant [180,195]. Because Mecp2 mice preferentially metabolize fat rather than glucose as their primary energy source, it is likely that other energy-sensing systems are affected. Specifically, energy metabolism affects the post-translational modification of proteins with O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc), a nutrient-driven epigenetic regulator [196,197]. The regulation of O-GlcNAc is required for many proteins involved in neurogenesis, and perturbation of O-GlcNAc protein modification has already been associated with many neurological diseases, including Alzheimer's [196,198]. Abnormal brain glucose-lipid homeostasis is also associated with oxidative stress in Alzheimer's [199]. RTT patients have increased oxidative burden and abnormal mitochondrial structure, while RTT animal models have defects in the mitochondrial respiratory chain [23,26,200–202] and oxidative changes in the brain [203]. Additionally, abnormal lipid metabolism is directly linked to inflammation [204], which is a component of pathology in both typical and atypical cases of RTT [205]. Notably, MeCP2 directly represses Irak1 and downregulation of the NF-κβ pathway improves symptoms in Mecp2 null mice [206].

The understanding of metabolic aspects of RTT pathology reveals potential therapeutic interventions. Statin drugs account for only one family of numerous metabolic modulators being developed to treat lipid accumulation or insulin resistance in Type II diabetes, which may be repurposed to treat RTT. Every year, new drug treatments are tested in Mecp2 animal models that rescue different aspects of RTT phenotypes. For example, the treatment of Mecp2 null mice with a protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) antagonist that was developed to treat Type II diabetes extended lifespan, decreased hindlimb clasping and improved motor performance [207]. Similarly, Trolox, a vitamin E derivative, normalized blood glucose levels, reduced oxidative stress and improved exploratory behaviour in Mecp2 mice [208]. Additionally, insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) partially rescued locomotor activity, respiratory function and heart rate in Mecp2 mice [209,210]. In addition to statins, phase 2 clinical trials for RTT are in progress for a list of potential therapies including IGF-1 (NCT01777542), EPI-743 (NCT01822249), triheptanoin (NCT03059160) and NNZ-2566 (NCT01703533). However, despite this progress, no single treatment has yet fixed every phenotype in Mecp2 mice or yet proved to effectively treat RTT symptoms.

While MeCP2 has been largely studied in CNS development and maturation, some clinically significant aspects of RTT may arise independently of MECP2 deficiency in the nervous system, and should be considered when planning any treatment strategy. Given the association between MeCP2 and HDAC3, non-specific HDAC inhibitors, commonly prescribed for seizure maintenance, should be approached cautiously as a treatment in RTT. Additionally, both RTT patients and Mecp2 mutant mice present with metabolic syndrome [15,180], oxidative stress [27,29], cardiac defects [211,212], decreased bone density [174,213] and urological dysfunction [214,215]. As CNS-targeted gene therapy becomes a more realistic therapeutic approach, peripheral deficiency of MeCP2 must be considered more than ever as these symptoms are likely to persist following targeted genetic treatment to the brain.

Furthermore, mutations in members of the NCoR1/SMRT-HDAC3 complex should be examined for roles in other childhood neurological diseases. Already, mutations in other components of the complex, TBLR1 and TBL1, have been associated with autism, intellectual disability, Pierpont syndrome, a disorder characterized by developmental delay and abnormal fat distribution in the distal limbs, and West syndrome, a disorder with RTT-like features [216–219]. Notably, six of these mutations in TBLR1 mapped to the WD40 domain of the protein and disrupted MeCP2-binding [150]. Therefore, the transcriptional function of the NCoR1/SMRT complex could represent a shared mechanism for autism spectrum disorders and other neurological conditions. Comparing the transcriptome of mice with genetic deletions of Mecp2 and members of the NCoR1/SMRT-HDAC3 complex may offer a comprehensive list of genes regulated by this interaction that can be studied to better understand disease pathology and exploited to develop potential treatments. Altogether, the progress in understanding the mechanistic basis for RTT pathology will continue to inform other neurological diseases and complex epigenetic mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the girls with Rett syndrome and their families, who provide the motivation for our group to try to alleviate symptoms. We thank Julie Ruston and Stephanie Almeida for their critical comments on the manuscript.

Data accessibility

This article has no additional data.

Authors' contributions

S.M.K., N.V. and M.J.J. drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors gave final approval before submission.

Competing interests

M.J.J. is a scientific founder of ArRETT Neurosciences, Inc., a company designed to provide treatments to Rett syndrome patients.

Funding

N.V. was supported by the Angel Ava Fund while writing this review.

References

- 1.Rett A. 1966. On a unusual brain atrophy syndrome in hyperammonemia in childhood. Wien. Med. Wochenschr. 1946, 723–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hagberg B, Aicardi J, Dias K, Ramos O. 1983. A progressive syndrome of autism, dementia, ataxia, and loss of purposeful hand use in girls: Rett's syndrome: report of 35 cases. Ann. Neurol. 14, 471–479. (doi:10.1002/ana.410140412) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burd L, Randall T, Martsolf JT, Kerbeshian J. 1991. Rett syndrome symptomatology of institutionalized adults with mental retardation: comparison of males and females. Am. J. Ment. Retard. 95, 596–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hagberg B. 2002. Clinical manifestations and stages of Rett syndrome. Ment. Retard. Dev. Disabil. Res. Rev. 8, 61–65. (doi:10.1002/mrdd.10020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hagberg B, Witt-Engerström I, Opitz JM, Reynolds JF. 1986. Rett syndrome: a suggested staging system for describing impairment profile with increasing age towards adolescence. Am. J. Med. Genet. 25, 47–59. (doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320250506) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Neul JL, et al. 2010. Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Ann. Neurol. 68, 944–950. (doi:10.1002/ana.22124) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haas RH. 1988. The history and challenge of Rett syndrome. J. Child Neurol. 3, S3–S5. (doi:10.1177/088307388800300102) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Townend GS, Marschik PB, Smeets E, van de Berg R, van den Berg M, Curfs LMG. 2016. Eye gaze technology as a form of augmentative and alternative communication for individuals with Rett syndrome: experiences of families in the Netherlands. J. Dev. Phys. Disabil. 28, 101–112. (doi:10.1007/s10882-015-9455-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jellinger K, Seitelberger F, Opitz JM, Reynolds JF. 1986. Neuropathology of Rett syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 25, 259–288. (doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320250528) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jellinger K, Armstrong D, Zoghbi HY, Percy AK. 1988. Neuropathology of Rett syndrome. Acta Neuropathol.. 76, 142–158. (doi:10.1007/BF00688098) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Armstrong DD. 1992. The neuropathology of the Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 14, S89–S98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaufmann WE, Moser HW. 2000. Dendritic anomalies in disorders associated with mental retardation. Cereb. Cortex 10, 981–991. (doi:10.1093/cercor/10.10.981) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taneja P, Ogier M, Brooks-Harris G, Schmid DA, Katz DM, Nelson SB. 2009. Pathophysiology of locus ceruleus neurons in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. J. Neurosci. 29, 12 187–12 195. (doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3156-09.2009) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zoghbi HY, Milstien S, Butler IJ, Smith EOB, Kaufman S, Glaze DG, Percy AK. 1989. Cerebrospinal fluid biogenic amines and biopterin in rett syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 25, 56–60. (doi:10.1002/ana.410250109) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Justice MJ, Buchovecky CM, Kyle SM, Djukic A. 2013. A role for metabolism in Rett syndrome pathogenesis: new clinical findings and potential treatment targets. Rare Dis. 1, e27265 (doi:10.4161/rdis.27265) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Segatto M, Trapani L, Di Tunno I, Sticozzi C, Valacchi G, Hayek J, Pallottini V. 2014. Cholesterol metabolism is altered in Rett syndrome: a study on plasma and primary cultured fibroblasts derived from patients. PLoS ONE 9, e104834 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104834) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Acampa M, Guideri F, Hayek J, Blardi P, De Lalla A, Zappella M, Auteri A. 2008. Sympathetic overactivity and plasma leptin levels in Rett syndrome. Neurosci. Lett. 432, 69–72. (doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2007.12.030) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blardi P, De Lalla A, D'Ambrogio T, Vonella G, Ceccatelli L, Auteri A, Hayek J. 2009. Long-term plasma levels of leptin and adiponectin in Rett syndrome. Clin. Endocrinol. 70, 706–709. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03386.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freilinger M, et al. 2014. Prevalence, clinical investigation, and management of gallbladder disease in Rett syndrome. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 56, 756–762. (doi:10.1111/dmcn.12358) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuishi T, Urabe F, Percy AK, Komori H, Yamashita Y, Schultz RS, Ohtani Y, Kuriya N, Kato H. 1994. Abnormal carbohydrate metabolism in cerebrospinal fluid in Rett syndrome. J. Child Neurol. 9, 26–30. (doi:10.1177/088307389400900105) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanefeld F, Christen HJ, Holzbach U, Kruse B, Frahm J, Hanicke W. 1995. Cerebral proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy in Rett syndrome. Neuropediatrics 26, 126–127. (doi:10.1055/s-2007-979742) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horska A, Naidu S, Herskovits EH, Wang PY, Kaufmann WE, Barker PB. 2000. Quantitative 1H MR spectroscopic imaging in early Rett syndrome. Neurology 54, 715–722. (doi:10.1212/WNL.54.3.715) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eeg-Olofsson O, Al-Zuhair AG, Teebi AS, Al-Essa MM. 1988. Abnormal mitochondria in the Rett syndrome. Brain Dev.. 10, 260–262. (doi:10.1016/S0387-7604(88)80010-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eeg-Olofsson O, Al-Zuhair AG, Teebi AS, Daoud AS, Zaki M, Besisso MS, Al-Essa MM. 1990. Rett syndrome: a mitochondrial disease?. J. Child Neurol. 5, 210–214. (doi:10.1177/088307389000500311) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakai S, Kameda K, Ishikawa Y, Miyamoto S, Nagaoka M, Okabe M, Minami R, Tachi N. 1990. Rett syndrome: findings suggesting axonopathy and mitochondrial abnormalities. Pediatr. Neurol. 6, 339–343. (doi:10.1016/0887-8994(90)90028-Y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cardaioli E, Dotti MT, Hayek G, Zappella M, Federico A. 1999. Studies on mitochondrial pathogenesis of Rett syndrome: ultrastructural data from skin and muscle biopsies and mutational analysis at mtDNA nucleotides 10463 and 2835. J. Submicrosc. Cytol. Pathol. 31, 301–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haas RH, Nasirian F, Hua X, Nakano K, Hennessy M. 1995. Oxidative metabolism in Rett syndrome. 2. Biochemical and molecular studies. Neuropediatrics 26, 95–99. (doi:10.1055/s-2007-979735) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sierra C, Vilaseca MA, Brandi N, Artuch R, Mira A, Nieto M, Pineda M. 2001. Oxidative stress in Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 23(Suppl 1), S236–S239. (doi:10.1016/S0387-7604(01)00369-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Felice C, et al. 2009. Systemic oxidative stress in classic Rett syndrome. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 47, 440–448. (doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leoncini S, De Felice C, Signorini C, Pecorelli A, Durand T, Valacchi G, Ciccoli L, Hayek J. 2011. Oxidative stress in Rett syndrome: natural history, genotype, and variants. Redox Rep. 16, 145–153. (doi:10.1179/1351000211Y.0000000004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shulyakova N, Andreazza AC, Mills LR, Eubanks JH. 2017. Mitochondrial dysfunction in the pathogenesis of Rett syndrome: implications for mitochondria-targeted therapies. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 11, 58 (doi:10.3389/fncel.2017.00058) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kerr AM, Armstrong DD, Prescott RJ, Doyle D, Kearney DL. 1997. Rett syndrome: analysis of deaths in the British survey. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiat. 6(Suppl 1), 71–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laurvick CL, de Klerk N, Bower C, Christodoulou J, Ravine D, Ellaway C, Williamson S, Leonard H. 2006. Rett syndrome in Australia: a review of the epidemiology. J. Pediatr. 148, 347–352. (doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.10.037) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson A, Wong K, Jacoby P, Downs J, Leonard H. 2014. Twenty years of surveillance in Rett syndrome: what does this tell us? Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 9, 87 (doi:10.1186/1750-1172-9-87) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sirianni N, Naidu S, Pereira J, Pillotto RF, Hoffman EP. 1998. Rett syndrome: confirmation of X-linked dominant inheritance, and localization of the gene to Xq28. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 63, 1552–1558. (doi:10.1086/302105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. 1999. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl- CpG-binding protein 2. Nat. Genet. 23, 185–188. (doi:10.1038/13810) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wan M, et al. 1999. Rett syndrome and beyond: recurrent spontaneous and familial MECP2 mutations at CpG hotspots. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 65, 1520–1529. (doi:10.1086/302690) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neul JL, Fang P, Barrish J, Lane J, Caeg EB, Smith EO, Zoghbi H, Percy A, Glaze DG. 2008. Specific mutations in Methyl-CpG-Binding Protein 2 confer different severity in Rett syndrome. Neurology 70, 1313–1321. (doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000291011.54508.aa) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weaving LS, et al. 2004. Mutations of CDKL5 cause a severe neurodevelopmental disorder with infantile spasms and mental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75, 1079–1093. (doi:10.1086/426462) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tao J, et al. 2004. Mutations in the X-linked cyclin-dependent kinase-like 5 (CDKL5/STK9) gene are associated with severe neurodevelopmental retardation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75, 1149–1154. (doi:10.1086/426460) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scala E, et al. 2005. CDKL5/STK9 is mutated in Rett syndrome variant with infantile spasms. J. Med. Genet. 42, 103–107. (doi:10.1136/jmg.2004.026237) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sartori S, Di Rosa G, Polli R, Bettella E, Tricomi G, Tortorella G, Murgia A. 2009. A novel CDKL5 mutation in a 47,XXY boy with the early-onset seizure variant of Rett syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A 149, 232–236. (doi:10.1002/ajmg.a.32606) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fehr S, et al. 2013. The CDKL5 disorder is an independent clinical entity associated with early-onset encephalopathy. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 21, 266–273. (doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.156) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guerrini R, Parrini E. 2012. Epilepsy in Rett syndrome, and CDKL5- and FOXG1-gene-related encephalopathies. Epilepsia 53, 2067–2078. (doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03656.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ariani F, et al. 2008. FOXG1 is responsible for the congenital variant of Rett syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83, 89–93. (doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mencarelli MA, et al. 2010. Novel FOXG1 mutations associated with the congenital variant of Rett syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 47, 49–53. (doi:10.1136/jmg.2009.067884) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Philippe C, Amsallem D, Francannet C, Lambert L, Saunier A, Verneau F, Jonveaux P. 2010. Phenotypic variability in Rett syndrome associated with FOXG1 mutations in females. J. Med. Genet. 47, 59–65. (doi:10.1136/jmg.2009.067355) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sung Jae LS, et al. 2001. Spectrum of MECP2 mutations in Rett syndrome. Brain Dev. 23(Suppl. 1), S138–S143. (doi:10.1016/S0387-7604(01)00339-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zappella M. 1992. The Rett girls with preserved speech. Brain Dev. 14, 98–101. (doi:10.1016/S0387-7604(12)80094-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koelsch KA, Webb R, Jeffries M, Dozmorov MG, Frank MB, Guthridge JM, James JA, Wren JD, Sawalha AH. 2013. Functional characterization of the MECP2/IRAK1 lupus risk haplotype in human T cells and a human MECP2 transgenic mouse. J. Autoimmun. 41, 168–174. (doi:10.1016/j.jaut.2012.12.012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schönewolf-Greulich B, et al. 2016. The MECP2 variant c.925C>T (p.Arg309Trp) causes intellectual disability in both males and females without classic features of Rett syndrome. Clin. Genet. 89, 733–738. (doi:10.1111/cge.12769) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tate P, Skarnes W, Bird A. 1996. The methyl-CpG binding protein MeCP2 is essential for embryonic development in the mouse. Nat. Genet. 12, 205–208. (doi:10.1038/ng0296-205) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lewis JD, et al. 1992. Purification, sequence, and cellular localization of a novel chromosomal protein that binds to Methylated DNA. Cell 69, 905–914. (doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90610-O) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohen DRS, Matarazzo V, Palmer AM, Tu Y, Jeon O-H, Pevsner J, Ronnett GV. 2003. Expression of MeCP2 in olfactory receptor neurons is developmentally regulated and occurs before synaptogenesis. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 22, 417–429. (doi:10.1016/S1044-7431(03)00026-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jung BP, Jugloff DGM, Zhang G, Logan R, Brown S, Eubanks JH. 2003. The expression of methyl CpG binding factor MeCP2 correlates with cellular differentiation in the developing rat brain and in cultured cells. J. Neurobiol. 55, 86–96. (doi:10.1002/neu.10201) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Samaco RC, Nagarajan RP, Braunschweig D, LaSalle JM. 2004. Multiple pathways regulate MeCP2 expression in normal brain development and exhibit defects in autism-spectrum disorders. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, 629–639. (doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh063) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kishi N, Macklis JD. 2005. Dissecting MECP2 function in the central nervous system. J. Child Neurol. 20, 753–759. (doi:10.1177/08830738050200091001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, Roskin KM, Pringle TH, Zahler AM, Haussler AD. 2002. The Human Genome Browser at UCSC. Genome Res.. 12, 996–1006. (doi:10.1101/gr.229102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mnatzakanian GN, et al. 2004. A previously unidentified MECP2 open reading frame defines a new protein isoform relevant to Rett syndrome. Nat. Genet. 36, 339–341. (doi:10.1038/ng1327) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kriaucionis S, Bird A. 2004. The major form of MeCP2 has a novel N-terminus generated by alternative splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1818–1823. (doi:10.1093/nar/gkh349) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Olson CO, Zachariah RM, Ezeonwuka CD, Liyanage VRB, Rastegar M. 2014. Brain region-specific expression of MeCP2 isoforms correlates with DNA methylation within Mecp2 regulatory elements. PLoS ONE 9, e90645 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090645) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pelka GJ, Watson CM, Christodoulou J, Tam PPL. 2005. Distinct expression profiles of Mecp2 transcripts with different lengths of 3′UTR in the brain and visceral organs during mouse development. Genomics 85, 441–452. (doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.12.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Coy JF, Sedlacek Z, Bächner D, Delius H, Poustka A. 1999. A complex pattern of evolutionary conservation and alternative polyadenylation within the long 3′ untranslated region of the methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 gene (MeCP2) suggests a regulatory role in gene expression. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 1253–1262. (doi:10.1093/hmg/8.7.1253) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.D'Esposito M, Quaderi NA, Ciccodicola A, Bruni P, Esposito T, D'Urso M, Brown SDM. 1996. Isolation, physical mapping, and Northern analysis of the X-linked human gene encoding methyl CpG-binding protein, MECP2. Mamm. Genome 7, 533–535. (doi:10.1007/s003359900157) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.McGowan H, Pang ZP. 2015. Regulatory functions and pathological relevance of the MECP2 3′UTR in the central nervous system. Cell Regen. 4, 9 (doi:10.1186/s13619-015-0023-x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nan X, Meehan RR, Bird A. 1993. Dissection of the methyl-CpG binding domain from the chromosomal protein MeCP2. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 4886–4892. (doi:10.1093/nar/21.21.4886) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lagger S, et al. 2017. MeCP2 recognizes cytosine methylated tri-nucleotide and di-nucleotide sequences to tune transcription in the mammalian brain. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006793 (doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006793) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nan X, Campoy FJ, Bird A. 1997. MeCP2 is a transcriptional repressor with abundant binding sites in genomic chromatin. Cell 88, 471–481. (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81887-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nan X, Tate P, Li E, Bird A. 1996. DNA methylation specifies chromosomal localization of MeCP2. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 414–421. (doi:10.1128/MCB.16.1.414) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lyst MJ, et al. 2013. Rett syndrome mutations abolish the interaction of MeCP2 with the NCoR/SMRT co-repressor. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 898–902. (doi:10.1038/nn.3434) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ebert DH, et al. 2013. Activity-dependent phosphorylation of MeCP2 threonine 308 regulates interaction with NCoR. Nature 499, 341–345. (doi:10.1038/nature12348) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chandler SPSP, Guschin D, Landsberger N, Wolffe APAP. 1999. The methyl-CpG binding transcriptional repressor MeCP2 stably associates with nucleosomal DNA. Biochemistry 38, 7008–7018. (doi:10.1021/bi990224y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bird A, Tweedie S. 1995. Transcriptional noise and the evolution of gene number. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B. 349, 249–253. (doi:10.1098/rstb.1995.0109) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tweedie S, Charlton J, Clark V, Bird A. 1997. Methylation of genomes and genes at the invertebrate-vertebrate boundary. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 1469–1475. (doi:10.1128/MCB.17.3.1469) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Stein R, Razin A, Cedar H. 1982. In vitro methylation of the hamster adenine phosphoribosyltransferase gene inhibits its expression in mouse L cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 79, 3418–3422. (doi:10.1073/pnas.79.11.3418) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nan X, Ng H-HH, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN, Bird A. 1998. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature 393, 386–389. (doi:10.1038/30764) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chahrour M, Jung SYY, Shaw C, Zhou X, Wong STCTC, Qin J, Zoghbi HYY. 2008. MeCP2, a key contributor to neurological disease, activates and represses transcription. Science 320, 1224–1229. (doi:10.1126/science.1153252) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Georgel PT, Horowitz-Scherer RA, Adkins N, Woodcock CL, Wade PA, Hansen JC. 2003. Chromatin compaction by human MeCP2: asssembly of novel secondary chromatin structures in the absence of DNA methylation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 32 181–32 188. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M305308200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baker SA, Chen L, Wilkins AD, Yu P, Lichtarge O, Zoghbi HY. 2013. An AT-hook domain in MeCP2 determines the clinical course of Rett syndrome and related disorders. Cell 152, 984–996. (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.038) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li R, et al. 2016. Misregulation of alternative splicing in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006129 (doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006129) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Young JI, et al. 2005. Regulation of RNA splicing by the methylation-dependent transcriptional repressor methyl-CpG binding protein 2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 17 551–17 558. (doi:10.1073/pnas.0507856102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kimura H, Shiota K. 2003. Methyl-CpG-binding protein, MeCP2, is a target molecule for maintenance DNA methyltransferase, Dnmt1. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4806–4812. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M209923200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kokura K, Kaul SC, Wadhwa R, Nomura T, Khan MM, Shinagawa T, Yasukawa T, Colmenares C, Ishii S. 2001. The Ski protein family is required for MeCP2-mediated transcriptional repression. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 34 115–34 121. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M105747200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nan X, Hou J, Maclean A, Nasir J, Lafuente MJ, Shu X, Kriaucionis S, Bird A. 2007. Interaction between chromatin proteins MECP2 and ATRX is disrupted by mutations that cause inherited mental retardation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 2709–2714. (doi:10.1073/pnas.0608056104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Adams VH, McBryant SJ, Wade PA, Woodcock CL, Hansen JC. 2007. Intrinsic disorder and autonomous domain function in the multifunctional nuclear protein, MeCP2. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 15 057–15 064. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M700855200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mollica L, Bessa LM, Hanoulle X, Jensen MR, Blackledge M, Schneider R. 2016. Binding mechanisms of intrinsically disordered proteins: theory, simulation, and experiment. Front. Mol. Biosci. 3, 52 (doi:10.3389/fmolb.2016.00052) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ausió J, de Paz AM, Esteller M. 2014. MeCP2: the long trip from a chromatin protein to neurological disorders. Trends Mol. Med. 20, 487–498. (doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2014.03.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bellini E, et al. 2014. MeCP2 post-translational modifications: a mechanism to control its involvement in synaptic plasticity and homeostasis? Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8, 236 (doi:10.3389/fncel.2014.00236) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ben-Shachar S, Chahrour M, Thaller C, Shaw CA, Zoghbi HY. 2009. Mouse models of MeCP2 disorders share gene expression changes in the cerebellum and hypothalamus. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 2431–2442. (doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp181) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pacheco NL, Heaven MR, Holt LM, Crossman DK, Boggio KJ, Shaffer SA, Flint DL, Olsen ML. 2017. RNA sequencing and proteomics approaches reveal novel deficits in the cortex of Mecp2-deficient mice, a model for Rett syndrome. Mol. Autism 8, 56 (doi:10.1186/s13229-017-0174-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stenson PD, Ball EV, Mort M, Phillips AD, Shiel JA, Thomas NST, Abeysinghe S, Krawczak M, Cooper DN. 2003. Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD): 2003 update. Hum. Mutat. 21, 577–581. (doi:10.1002/humu.10212) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Goto T, Monk M. 1998. Regulation of X-chromosome inactivation in development in mice and humans. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62, 362–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Millar CB. 2002. Enhanced CpG mutability and tumorigenesis in MBD4-deficient mice. Science 297, 403–405. (doi:10.1126/science.1073354) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Trappe R, Laccone F, Cobilanschi J, Meins M, Huppke P, Hanefeld F, Engel W. 2001. MECP2 mutations in sporadic cases of Rett syndrome are almost exclusively of paternal origin. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68, 1093–1101. (doi:10.1086/320109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bienvenu T, et al. 2000. MECP2 mutations account for most cases of typical forms of Rett syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 1377–1384. (doi:10.1093/HMG/9.9.1377) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cuddapah VA, et al. 2014. Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 (MECP2) mutation type is associated with disease severity in Rett syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 51, 152–158. (doi:10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-102113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Knudsen GPS, Neilson TCS, Pedersen J, Kerr A, Schwartz M, Hulten M, Bailey MES, Ørstavik KH. 2006. Increased skewing of X chromosome inactivation in Rett syndrome patients and their mothers. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 14, 1189–1194. (doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201682) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]