Abstract

Patients with cirrhosis have high admission and readmission rates, and it is estimated that a quarter are potentially preventable. Little data are available regarding nonmedical factors impacting triage decisions in this patient population. This study sought to explore such factors as well as to determine provider perspectives on low‐acuity clinical presentations to the emergency department, including ascites and hepatic encephalopathy. A survey was distributed in four liver transplant centers to both emergency medicine and hepatology providers, who included attending physicians, house staff, and advanced practitioners; 196 surveys were returned (estimated response rate 50.6%). Emergency medicine providers identified several influential nonmedical factors impacting inpatient triage decisions, including input from a hepatologist (77.7%), inadequate patient access to outpatient specialty care (68.6%), and patient need for diagnostic testing for a procedure (65.6%). When given patient‐based scenarios of low‐acuity cases, such as ascites requiring paracentesis, only 7.0% believed patients should be hospitalized while 48.9% said these patients would be hospitalized at their institution (P < 0.0001). For mild hepatic encephalopathy, the comparable numbers were 19.5% and 55.2%, respectively (P < 0.001). Several perceived barriers were cited for this discrepancy, including limited resources both in the outpatient setting and emergency department. Most providers believed that an emergency department observation unit protocol would influence triage toward an emergency department observation unit visit instead of inpatient admission for both ascites requiring large volume paracentesis (83.2%) and mild hepatic encephalopathy (79.4%). Conclusion: Many nonmedical factors that influence inpatient triage for patients with cirrhosis could be targeted for quality improvement initiatives. In some scenarios, providers are limited by resource availability, which results in triage to an inpatient admission even when they believe this is not the most appropriate disposition. (Hepatology Communications 2018;2:237‐244)

Abbreviations

- CRC

clinical resource coordinator

- ED

emergency department

- EDOU

emergency department observation unit

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- LVP

large volume paracentesis

Introduction

Hospital readmissions have garnered recent attention, particularly after the creation of the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services Readmissions Reductions Program that financially penalizes hospitals for readmissions.1 Although cirrhosis is not currently included in this policy, other insurers have adopted readmission penalties for all covered patients, including those with cirrhosis. Additionally, readmissions pose a financial burden to patients and their family members and may also be a marker of poor quality care in some circumstances.

Multiple studies have confirmed high readmission rates for patients with decompensated cirrhosis, with rates of approximately 15%‐30% within 30 days and approximately 50% in 3 months.2, 3, 4 Liver transplant centers in particular are likely to have a higher readmission rate given that they attract sick patients with a higher expected mortality rate. Several studies have examined reasons underlying these high rates and have cited a relationship to serious complications of cirrhosis.2, 3, 4, 5

Although most hospitalizations are warranted, about 25% of readmissions for patients with cirrhosis are felt to be preventable.3 Included in these preventable admissions are patients with cirrhosis who present to emergency departments (EDs) with low‐acuity clinical presentations, such as ascites requiring large volume paracenteses (LVPs) or mild confusion due to hepatic encephalopathy requiring lactulose administration.3, 6, 7, 8 Prior studies have questioned whether patients in these scenarios truly warrant admission to the hospital as these patients have been shown to be safely managed with intensive outpatient treatment instead.6, 7, 8 Although retrospective analyses document that these scenarios occur frequently and urge providers to reconsider if admission is warranted, the nonmedical factors that influence the decision to admit patients with cirrhosis have not been previously examined.

This study aimed to 1) identify nonmedical factors that influence emergency medicine providers toward an inpatient triage decision for patients with cirrhosis, 2) identify nonmedical factors that influence emergency medicine providers toward an (outpatient) observation unit visit for patients with cirrhosis instead of inpatient admission for patients with cirrhosis, and 3) explore both hepatology and emergency medicine providers' perspectives on triaging patients with cirrhosis who present to the ED with low‐acuity clinical presentations, such as ascites requiring paracentesis and mild hepatic encephalopathy. The ultimate goal is to further understand opportunities for intervention to prevent admissions for patients with cirrhosis.

Participants and Methods

This was a multicenter cross‐sectional survey study among emergency medicine and hepatology providers at four large urban academic medical centers, each with a liver transplant program. The University of Pennsylvania's Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this study as the sponsoring institution. Additional IRB approval was obtained from Johns Hopkins Hospital and Mount Sinai Hospital per institutional requirements. Yale New Haven Hospital agreed to survey distribution under the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania's approved IRB. These four institutions were selected given their large patient populations with cirrhosis and similar rates of liver transplantation, which give providers experience in triaging patients with cirrhosis. All of the hospitals had observation units; three of the units were managed by emergency medicine providers and one was managed by hospitalists.

STUDY SUBJECTS AND PARTICIPATION CRITERIA

Inclusion Criteria

All physicians (i.e., attending physicians and house staff) and advanced practitioners (i.e., nurse practitioners and physician assistants) in the emergency medicine and gastroenterology divisions were eligible to receive the survey.

Exclusion Criteria

Providers had to have indicated experience in patient triage for patients with cirrhosis. An initial survey question asked if the provider is involved in the triage of patients with cirrhosis in some capacity, such as urgent clinic visits, patient phone calls, or directly in the ED. If the provider indicated “no,” they were instructed to not proceed with the survey. Previous participation in this study also excluded providers.

SURVEY INSTRUMENT

The survey contained two sections. The first section was distributed only to emergency medicine providers. Providers were first asked an open‐ended hypothesis‐generating question regarding their initial concerns when triaging a patient with cirrhosis. They were then given a series of nonmedical factors potentially impacting triage to an inpatient admission, adapted from a prior study, with a 5‐point Likert scale to indicate how influential each factor is in the decision‐making process.9 The Likert scale ranged from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree. A second set of similar questions evaluated other financial and resource utilization factors that might impact triage to an observation unit, again using a 5‐point Likert scale.

The second section of the survey was scenario‐based (see Supporting Material) and was distributed to both emergency medicine providers and hepatology providers. Providers were given two patient‐based scenarios (one for ascites requiring LVP and one for mild hepatic encephalopathy) and asked what they believed the most appropriate triage disposition should be, what the most common disposition is at their institution, and to describe any potential discrepancies between these two answers.

Additionally, providers were asked if the presence of an observation unit protocol for each scenario would make them more likely to triage to an observation unit instead of an inpatient admission, using a 5‐point Likert scale from Strongly Disagree to Strongly Agree.

The survey was pilot tested prior to distribution and subsequently edited for readability and understanding for all levels of providers.

SURVEY DISTRIBUTION AND DATA COLLECTION

Surveys were distributed during faculty meetings, house staff conferences, and other similar divisional meetings at each institution. Paper distribution was used to increase response rates for physicians, who are often busy and who have demonstrated poor response rates in electronic surveys.10 When possible, sign‐in sheets were distributed during each meeting solely to identify the number of unique attendees and to identify potential repeat attendees from prior survey distribution efforts. These were not linked to any surveys, and no identifiable information was collected.

Survey distribution was scheduled to occur at all four sites from November 1, 2016, to November 1, 2017. This time frame was selected to ensure that distribution could occur over several divisional meetings to obtain an adequate sample of providers. At one site, there was a delay, and data collection was conducted from March 1, 2017, to May 1, 2017. At the other sites, we noted low response rates for emergency medicine providers during the initial data collection; therefore, we extended data collection for all sites until May 1, 2017.

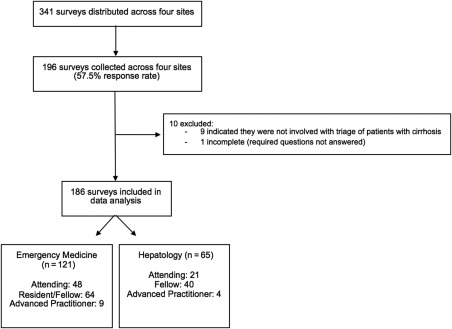

Study data were aggregated by a single study member who entered and managed the data using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure web‐based data collection tool, hosted at the University of Pennsylvania.11 The data collection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for data collection.

REQUIRED QUESTIONS

The only required questions in the survey were the initial demographic questions (institution, provider role, division) and a question asking if the provider is involved with patient triage in some capacity. If one of these required questions were unanswered, the survey was considered incomplete and excluded. Otherwise, all surveys were included, even if partially completed. Missing data were not imputed.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Response rate was calculated as number of surveys received divided by number of unique individuals who received the survey at a given institution throughout the various conferences or meetings. If the number of unique individuals was not known, the total number of providers in the division was used as the denominator instead. The latter provided a more conservative calculation of response rate.

Descriptive statistics were calculated using frequencies and percentages. Comparative statistics included Fisher's exact test and chi‐square analysis. Open‐ended questions were analyzed with a content analytic approach in which responses were grouped into categories and summarized using descriptive statistics. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata, version 14.

Results

The overall response rate was 50.6% (196/387). By specialty group, the response rate for hepatology providers was 63.2% (range across institutions, 29.7%‐90.0%) and the response rate for emergency medicine providers was 39.4% (range, 23.8%‐72.9%).

Of the 387 distributed surveys, 196 responses were received from the four institutions. Of these, one was incomplete as demographic questions were unanswered and 9 additional respondents indicated that they did not triage patients with cirrhosis. There were subsequently 186 eligible survey responses for data analysis.

Of the total eligible respondents, 65.1% were emergency medicine providers and 35.0% were hepatology providers. Across institutions, 37.1% of respondents were attending physicians, 55.9% were residents or fellows, and 7.0% were advanced practitioners.

ED TRIAGE OF PATIENTS WITH CIRRHOSIS

ED providers were asked in an open‐ended question to describe initial concerns when triaging a patient with cirrhosis. Of the 108 responses, the most common themes included determination of whether the patient had evidence of infection, such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (50.0%), gastrointestinal bleeding (40.7%), and altered mental status or hepatic encephalopathy (35.9%). Several respondents also mentioned specifically touching base with the consulting hepatology team (11.0%), who may have been familiar with the patient, and of those, 2 respondents noted that if the hepatology team provided reassurance for discharge or indicated a need for admission, both types of input would impact their triage decision in either direction. Additionally, other respondents mentioned determining need for paracentesis (10.2%) and concern for inadequate outpatient follow‐up (9.3%).

The most notable nonmedical factors impacting emergency medicine triage decisions for admission, as defined by a respondent indicating agree or strongly agree, were input from hepatologist (77.7%), inadequate access to outpatient specialty care (68.6%), need for diagnostic testing or a procedure (65.6%), and living situation or lack of social support (55.4%).

In terms of deciding triage between an ED observation unit (EDOU) or inpatient admission, emergency medicine providers indicated that the most influential factors impacting this decision were anticipated stay less than 24 hours (81.7%), input from a hepatologist (74.2%), and access to early outpatient appointments (69.8%). Additionally, 45.0% of respondents felt that input from a clinical resource coordinator (CRC) was influential in this triage decision.

ED AND HEPATOLOGY TRIAGE OF LOW‐ACUITY CIRRHOTIC PRESENTATIONS

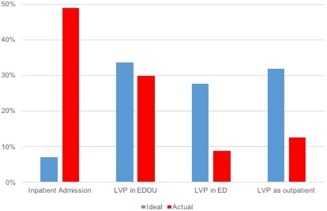

When presented with the scenario of a patient requiring only an LVP (see Supporting Material), 13 respondents (7.0%) believed that this warranted an inpatient admission (i.e., ideal disposition); however, 90 respondents (48.9%) believed that inpatient admission was the most common (i.e., actual) disposition at their institution (Fig. 2). Although respondents believed that the most ideal disposition was discharge (93.0%), they varied in terms of whether the patient should have the LVP done as an outpatient (31.9%), in the ED (27.6%), or in the EDOU (33.5%) prior to discharge. There was a statistically significant difference in what providers assessed was the most appropriate disposition compared to the most common disposition (χ2 = 63.66, P < 0.0001).

Figure 2.

Chi‐square analysis shows that there is a statistically significant difference in the most appropriate disposition compared to the most common disposition for patients requiring only an LVP (χ2 = 63.66, P < 0.0001).

There was also a difference in responses between hepatology and emergency medicine providers for the most appropriate disposition (χ2 = 14.85, P = 0.002; Supporting Fig. S1). More emergency medicine providers (8.3%) believed that the LVP should occur as part of an inpatient admission compared to hepatology providers (4.6%), and more emergency medicine providers believed the LVP should occur as an outpatient (36.7%) compared to hepatology providers (23.8%). This discrepancy is related to the finding that 44.6% of hepatology providers believed the paracentesis should occur in the ED prior to discharge and 27.7% believed the paracentesis should occur in an EDOU.

The most commonly cited open‐ended reasons (total n = 65) for differences between appropriate disposition compared to actual disposition were established practice patterns in the ED (61.5%) and inadequate outpatient resources (16.9%). For those who felt that a patient would not get discharged from the ED, respondents cited several reasons for this, including the risk of litigation and attempts to improve patient satisfaction.

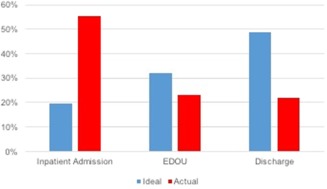

When presented with a patient with mild hepatic encephalopathy, known medication noncompliance to lactulose, lactulose administration in the ED, and subsequent resolution of symptoms (Supporting Material), there was a range of responses with no clear majority. Ninety respondents (48.7%) believed that the patient should be discharged from the ED with outpatient follow‐up, with the remaining respondents split between inpatient admission (19.5%) or a brief stay in an EDOU (31.9%). In contrast, the most commonly reported actual disposition was inpatient admission (55.2%; Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Chi‐square analysis shows that there is a statistically significant difference in the most appropriate disposition compared to the most common disposition for admission or discharge for patients with mild hepatic encephalopathy, known medication noncompliance to lactulose, lactulose administration in the ED, and subsequent resolution of symptoms (χ2 = 63.50, P < 0.0001).

There was no difference in responses between emergency medicine providers and hepatology providers for this hepatic encephalopathy scenario (χ2 = 5.91, P = 0.052; Supporting Fig. S2).

When respondents were asked in an open‐ended question for reasons for a potential discrepancy between the most appropriate and most common disposition, 47 responses were received citing that they are often “over cautious” or “over conservative” (34.0%), time constraints giving two doses of lactulose in the ED (21.3%), difficulty expediting outpatient follow‐up (14.9%), or ruling out other triggers for hepatic encephalopathy, such as infection or gastrointestinal bleeding (8.5%).

Additionally, most providers believed that an observation unit protocol would influence triage toward an EDOU visit instead of inpatient admission for both ascites requiring LVP (83.2%) and mild hepatic encephalopathy (79.4%).

Discussion

We found that there are several nonmedical factors that influence triage to an inpatient admission, even when providers believe it is not the most appropriate disposition. These nonmedical factors include inadequate resources to early outpatient appointments, inadequate resources to perform procedures, or monitoring in the ED. Our study highlights the impact that inadequate resources may have on inpatient triage and sheds light on the known higher admission and readmission rates observed in patients with cirrhosis.

Our findings also stress the need for social outreach programs for this patient population that could provide a better social support system for patients at home and provide greater access to outpatient specialty care, as these factors were reported to influence inpatient admission. A systematic review of quality improvement initiatives for patients with chronic liver disease shows that several interventions attempting to address these gaps have been unsuccessful, including case management, postdischarge phone calls, home visits to reduce readmissions, and educational programs.12

Prior literature has shown the benefit of incorporating specialty consults in the management of hospitalized patients with cirrhosis during inpatient admissions.13, 14 Our study results, however, highlight a new potential need for hepatology input on triage decisions in the ED. In our study, emergency medicine providers often cited the importance of hepatology input in patient triage, indicating a high level of impact on their decision making for inpatient admission, observation unit status, or discharge with outpatient follow‐up. This is particularly important given that there was a trend that hepatology providers were often more comfortable with avoiding inpatient admissions in low‐acuity scenarios than emergency medicine providers, although this was not consistently statistically significant. This underscores the opportunity for hepatologists to engage closely with emergency medicine providers regarding patients who present to the ED to actively identify and avoid preventable admissions.

Our results were notable in that 45.0% of emergency medicine providers surveyed indicated that input from a CRC was influential in deciding triage to an observation unit or inpatient admission. The role of the CRC is typically to corroborate insurance qualifications for an inpatient admission with the patient's clinical scenario and medical needs. This allows the hospital to determine prior to triage if an inpatient admission or observation unit stay would be billed and reimbursed appropriately. Studies have shown that providers are impacted by financial incentives and reimbursement,15, 16 but there is less evidence on the influences of insurance requirements and hospital reimbursement on inpatient triage. Additionally, it would be useful to understand whether providers opt toward admission if they believe the hospital will get paid for it or if they settle with observation unit stays even when they believe inpatient admission is in the best interest of the patient, or possibly both.

Our study shows that there may be potential to identify low‐acuity patient presentations to target efforts to reduce admissions. The case‐based scenarios revealed that most providers (92.9%) believed patients with cirrhosis and ascites requiring LVPs could be managed outside of an inpatient admission. Despite providers believing an inpatient admission is not necessary, patients are still getting admitted, given the lack of resources cited. Although there was a difference between hepatology and emergency medicine responses, the trends were in similar directions, and a majority of both groups believed that an EDOU protocol would be beneficial in this scenario. A study by Morando et al.6 showed the potential impact of a “day hospital” in which patients who need procedures, such as paracenteses or esophageal band ligation, could have them done under an outpatient status, which was found to have both mortality and cost benefits.

Similarly, for patients with mild hepatic encephalopathy, most providers do not think inpatient admission is warranted, yet they believe this is still the most likely outcome. Again, forming and studying EDOU protocols using quality metric outcomes could be a potential next step. A prospective quality improvement initiative using an electronic decision support tool to manage patients with overt hepatic encephalopathy showed reductions in length of stay and readmission.17 Although this was for hospitalized patients, a similar model for mild hepatic encephalopathy in an observation unit could be trialed and studied.

There are several limitations to this study. First, our response rate of 50.6% was modest. However, physicians, particularly specialists, historically have a low response rate, which is also decreasing over time.10, 18 We selected paper survey distribution as opposed to web‐based distribution as we believed providers were more likely to complete surveys during meetings as part of their workflow. As a result, our response rates were higher than those documented in prior physician surveys in which response rates ranged from 10%‐46%.10, 18 Additionally, there is no necessary relationship between the response rate and presence of nonresponse bias, and our outreach efforts were directed to all types of providers.19 Second, paper survey distribution could not allow us to guarantee that a provider did not take the survey more than once. However, given that we sampled a highly literate professional population, we believe that repeated responses are unlikely. Third, there may be a gap between what providers say occurs and what actually occurs in terms of patient management. Therefore, it is important that any quality improvement initiatives created to prevent admissions be supplemented with objective patient data collection and outcome reporting. Finally, the generalizability of this study to smaller community hospitals may be limited given that this survey was distributed only to providers in transplant academic centers. However, concerns regarding high readmission rates in patients with cirrhosis that would warrant quality improvement interventions are likely more pressing at institutions with a high volume of patients with cirrhosis, similar to our sites. Additionally, telemedicine efforts could be a potential solution for patients who do not live near a transplant center. At one of our participating institutions, a successful telemedicine program reduced readmissions for volume overload and hepatic encephalopathy.20 The intervention entailed providing patients with a 4G tablet, at‐home monitoring of vital signs, medication adherence, and new symptom tracking with registered nurse and medical doctor interventions by phone or video chat. This model effectively reduced readmissions at this institution and could serve as a model for future quality efforts.

In summary, our study provides insight into several nonmedical factors that play a role in triage to an inpatient admission for patients with cirrhosis. It also provides a basis to consider the development of observation unit protocols to prevent admissions for patients with cirrhosis who present with low‐acuity clinical presentations, such as ascites requiring paracentesis or mild hepatic encephalopathy.

Supporting information

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep4.1141/full.

Supporting Information 1

Supporting Information Figure 1

Supporting Information Figure 2

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

Supported by a National Institutes of Health T32 grant (no. DK007740 to S.M.S.).

REFERENCES

- 1. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Readmissions reduction program (HRRP) . https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Published April 18, 2016. Accessed June 2017.

- 2. Bajaj JS, Reddy KR, Tandon P, Wong F, Kamath PS, Garcia‐Tsao G, et al.; North American Consortium for the Study of End‐Stage Liver Disease. The 3‐month readmission rate remains unacceptably high in a large North American cohort of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2016;64:200‐208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Volk ML, Tocco RS, Bazick J, Rakoski MO, Lok AS. Hospital readmissions among patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:247‐252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Agrawal K, Kumar P, Markert R, Agrawal S. Risk factors for 30‐day readmissions of individuals with decompensated cirrhosis. South Med J 2015;108:682‐687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ganesh S, Rogal SS, Yadav D, Humar A, Behari J. Risk factors for frequent admissions and barriers to transplantation in patients with cirrhosis. PLoS One 2013;8:e55140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morando F, Maresio G, Piano S, Fasolato S, Cavallin M, Romano A, et al. How to improve care in outpatients with cirrhosis and ascites : a new model of care coordination by consultant hepatologists. J Hepatol 2013;59:257‐264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fagan KJ, Zhao EY, Horsfall LU, Ruffin BJ, Kruger MS, McPhail SM, et al. Burden of decompensated cirrhosis and ascites on hospital services in a tertiary care facility: time for change? Intern Med J 2014:865‐872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. White A. Outpatient interventions for hepatology patients with fluid retention: a review and synthesis of the literature. Gastroenterol Nurs 2014;37:236‐244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lewis Hunter AE, Spatz ES, Bernstein SL, Rosenthal MS. Factors influencing hospital admission of non‐critically ill patients presenting to the emergency department: a cross‐sectional study. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:37‐44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, Noseworthy T, Beck CA, Dixon E, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web‐based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol 2015;15:32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – A metadata‐driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009;42:377‐381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tapper EB. Building effective quality improvement programs for liver disease: a systematic review of quality improvement initiatives. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:1256‐1265.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Desai AP, Satoskar R, Appannagari A, Reddy KG, Te HS, Reau N, et al. Co‐management between hospitalist and hepatologist improves the quality of care of inpatients with chronic liver disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014;48:e30‐e36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ghaoui R, Friderici J, Desilets DJ, Lagu T, Visintainer P, Belo A, et al. Outcomes associated with a mandatory gastroenterology consultation to improve quality of care of patients hospitalized with decmpensated cirrhosis. J Hosp Med 2015;10:236‐241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Melichar L. The effect of reimbursement on medical decision making: Do physicians alter treatment in response to a managed care incentive? J Health Econ 2009;28:902‐907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Clemens J, Gottlieb JD. Do physicians' financial incentives affect medical treatment and patient health? Am Econ Rev 2014;104:1320‐1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tapper EB, Finkelstein D, Mittleman MA, Piatkowski G, Chang M, Lai M. A quality improvement initiative reduces 30‐day rate of readmission for patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:753‐759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. McLeod CC, Klabunde CN, Willis GB, Stark D. Health care provider surveys in the United States, 2000‐2010: a review. Eval Health Prof 2013;36:106‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. James KM, Ziegenfuss JY, Tilburt JC, Harris AM, Beebe TJ. Getting physicians to respond: the impact of incentive type and timing on physician survey response rates. Heath Serv Res 2011;4(Pt.1):232‐242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Halpern SD, Asch DA. Commentary: improving response rates to mailed surveys: what do we learn from randomized controlled trials? Int J Epidemiol 2003;32:637‐638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Khungar V, Serper M, Peyton D, Mehta S, Norris A, Huffenberger A, et al. Use of an innovative telehealth platform to reduce readmissions and enable patient‐centered care in cirrhotic patients [Abstract]. Hepatology 2017;66(Suppl. 1):94A‐95A. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found at onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/hep4.1141/full.

Supporting Information 1

Supporting Information Figure 1

Supporting Information Figure 2