Abstract

Objectives

Self-collection of cervico-vaginal samples for HPV testing has the potential to make cervical cancer screening more accessible to underscreened women. We evaluated the acceptability and ease of use of home-based HPV self-collection within a diverse population of low-income, infrequently screened women.

Methods

Participants were low-income women from North Carolina who had not received Pap testing in 4 or more years. Eligible women received a self-collection kit containing instructions and a brush for home-based sample collection. A total of 227 women returned a self-collected sample by mail and completed a questionnaire to assess their experiences with HPV self-collection. We described acceptability measures and used logistic regression to identify predictors of overall positive thoughts about the self-collection experience.

Results

Nearly all women were willing to perform HPV self-collection again (98%) and were comfortable receiving the self-collection kit in the mail (99%). Overall, 81% of participants reported positive thoughts about home-based self-collection. Women with at least some college education and those who were divorced, separated, or widowed were more likely to report overall positive thoughts. Aspects of self-collection that participants most commonly reported liking included convenience (53%), ease of use (32%), and privacy (23%). The most frequently reported difficulties included uncertainty that the self-collection was done correctly (16%) and difficulty inserting the self-collection brush (16%).

Conclusions

Home-based self-collection for HPV was a highly acceptable screening method among low-income, underscreened women and holds the promise to increase access to cervical cancer screenings in this high-risk population.

Keywords: cervical neoplasia, HPV, screening

MeSH: Uterine cervical neoplasms, early detection of cancer, papillomavirus infections, United States, female, humans

INTRODUCTION

In the United States (U.S.), cervical cancer incidence and mortality have decreased in recent decades, largely due to widespread screening with cytology (Pap testing).1 However, in 2017, an estimated 12,820 U.S. women will be diagnosed with invasive cervical cancer,1 with over half of new cases among women who have been screened infrequently or not at all.2 The primary cause of invasive cervical cancer and precancerous lesions is persistent infection with high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV). Current cervical cancer screening recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) for women ages 30 and older include Pap testing alone every 3 years, or HPV testing with Pap testing (co-testing) every 5 years.3 Recently, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved HPV testing as a stand-alone method of primary screening for cervical cancer,4 although HPV self-collection is not yet FDA-approved for clinical use. Self-collection of cervico-vaginal samples at home with return by mail for HPV testing is a promising approach that may alleviate barriers to clinic-based cervical cancer screening, such as transportation limitations or discomfort with pelvic examinations.5–7

In European studies, mailed delivery of self-collection kits for HPV testing has increased cervical cancer screening of under- and never-screened women compared to mailed written reminders to attend in-clinic screening.8–14 Systematic reviews have found that HPV testing of self-collected samples has a sensitivity for detection of high grade lesions (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 or more severe [CIN2+]) comparable to HPV testing of physician-collected samples.15 The self-collection method may complement current screening protocols by reaching women who have difficulty accessing or are resistant to clinic-based screening, making it especially relevant for underscreened women (i.e., those who have not consistently completed screening at recommended intervals).3 If implemented as a primary screening method, HPV self-collection conducted by mail could reduce the screening burden by requiring that only self-collection HPV-positive women attend follow-up in-clinic screening.

Self-collection has been found to be highly acceptable in a wide range of demographic groups and geographic locations worldwide.16 Several U.S.-based studies have found high acceptability among low-income populations when self-collection kits and results are delivered face-to-face in community settings.17–29 However, acceptability in U.S. women who are both low-income and underscreened has not been well characterized. Due to their increased risk of developing invasive cervical cancer, this is a priority population for screening by self-collection.2, 30 Mail-based HPV self-collection could be particularly helpful to low-income and rural women who face transportation barriers. To our knowledge, two prior U.S. studies have investigated acceptability among women who received HPV self-collection kits by mail,18, 31 though neither focused exclusively on underscreened or low-income women.

To expand the evidence base regarding acceptability of HPV testing conducted by mailed self-collected specimens, we present here data on the acceptability of home-based self-collection among low-income, underscreened women from 10 counties in North Carolina.

METHODS

Recruitment and selection of participants

Between January 2010 and September 2011, we recruited women from Wake, Durham, Harnett, Guilford, Wayne, Cumberland, Robeson, Richmond, Hoke, and Scotland counties. Detailed study methods have been presented elsewhere.32 Recruitment involved flyers and posters, referral of callers from the United Way 2-1-1 social assistance hotline, and direct outreach in locations likely to be visited by low-income women. Potential participants called the study’s hotline and were screened for study eligibility. Women were eligible if they lived in North Carolina, were aged 30 to 65, were not pregnant, had not undergone a hysterectomy, and were low income. Low income was defined as having children who qualified for the federal school lunch program; having Medicaid or Medicare Part B insurance, or being uninsured and living ≤200% of the federal poverty level. Eligibility criteria also required that women had not had Pap testing in the previous 4 years, including women who had never had a Pap test (n=4). The eligibility criteria for age, income, and insurance ensured that women were eligible for free clinic appointments, follow-up screening, and treatment through the North Carolina Breast and Cervical Cancer Control Program, Medicaid, or their own insurance. Among 429 women who were sent an HPV self-collection kit, 275 (64%) returned a self-collected sample. Of these, 227 women (53% of total) also completed the acceptability questionnaire and are included in this present analysis. The acceptability questionnaire was completed by only 3 women who did not return a sample (2%), so it is not possible to reliably make comparisons of self-collection acceptability between kit returners and non-returners.

Procedures

Participants received a self-collection “kit” containing a Viba brush (Rovers Medical Devices, BV; Oss, The Netherlands) for cervico-vaginal sample collection, illustrated instructions, and a prepaid return mailer. The kit also contained study consent forms and contact information for clinics in their county that perform free or low-cost Pap testing. We developed and pilot-tested the illustrated instructions for comprehension by low-literacy women. To complete self-collection, women were asked to insert the brush as far as it could comfortably go, rotate it five times, and remove it. Participants then removed the brush head from the handle and placed it into a small vial of Scope mouthwash, a validated liquid preservation media for HPV DNA testing.33 The Viba brush is about 8 inches long, with a handle 1/4 inch in diameter and brush head with long, flexible plastic bristles. Self-collected samples were returned by mail using the prepaid return mailer. Women who did not return a self-collected sample were sent a reminder letter at 2 weeks, followed by a phone call at 3 weeks, and a second letter at 1 month.

Study call center staff contacted women who returned their self-collected samples and provided them with their HPV results. Staff delivering HPV results were based in a call center run by the American Sexual Health Association (ASHA), a national organization that promotes the sexual health of individuals, families and communities.34 ASHA staff are well-trained in providing support on the meaning of HPV results. On that call, ASHA staff administered an acceptability questionnaire. Given that in-clinic Pap testing or co-testing are the screening methods currently included in USPSTF guidelines,30 ASHA staff also provided participants with information on clinics in their county offering free or low-cost cervical cancer screening, and encouraged them to obtain in-clinic screening. This further allowed an assessment of in-clinic attendance stratified by home HPV self-collection results (positive, negative). For future program implementation, women with HPV self-collection negative results would be considered screening complete until the next screening round. After the study staff received notification of Pap testing completion by return of a postcard by the participant, or after two months without notification, staff called participants to complete a follow-up questionnaire. Participants received $30 for returning the self-collected sample and completing the acceptability questionnaire, $10 for reporting completion of Pap testing, and $5 for completing the follow-up questionnaire. Approximately 18 months after self-collection kits were originally mailed, additional attempts were made to contact women who had not returned a sample to obtain basic acceptability and demographic data.

The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the study protocol (IRB no. 08-2099). Complete protocol has been described in Smith et al.32

Questionnaires

The acceptability questionnaire obtained data on socio-demographic characteristics and medical and reproductive history. Participants’ attitudes toward using self-collection, difficulties with self-collection, and concerns about receiving or returning the self-collected sample by mail were also assessed. The follow-up questionnaire assessed women’s willingness to perform self-collection again. Questionnaire items included previously validated measures of variables such as perceived risk and attitudes, and items developed specifically for the study, which were pilot tested for comprehension (Supplementary file 1). Study materials and questionnaires used the term “self-test” and “self-testing” for the self-collection and testing process, as this phrasing was found to be better understood by women in the lay population.

Measures

To assess overall attitude about the self-collection experience, we asked, “Overall, are your thoughts about the self-test mostly positive, mostly negative, or neutral?” We created a binary variable of ‘mostly positive’ vs ‘neutral/mostly negative’ to assess predictors of positive thoughts. We excluded from this analysis 29 women with a “refused,” “don’t know,” or missing response. The acceptability questionnaire contained open-ended items such as, “What did you like about the self-test,” and closed-ended items, such as “Were you comfortable receiving the kit in the mail?” We categorized open-ended responses inductively based on similar thematic elements. To assess difficulties with the self-collection, we used responses to the open-ended question, “What would you say was the most difficult part about doing the self-test?” For these analyses, we categorized responses of “don’t know” and “refused” with “nothing.”

Statistical analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses for measures of self-collection acceptability and ease of use. Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to identify characteristics associated with mostly positive thoughts. Both age-adjusted and multivariable analyses were conducted. Multivariable models were adjusted for age, as well as education and marital status, which were significantly associated with positive thoughts in the age-adjusted model.

Analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

The median age of the 227 participating women was 44 years (range 30–64). Most were Black (55%), had a high school education or less (62%), were uninsured (68%), current smokers (51%), and lived in rural areas (79%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and predictors of overall positive thoughts about the HPV self-collection among infrequently screened women in North Carolina (n=227)

| Characteristic | Total N(%)*† | Overall positive thoughts (%) | Age-adjusted OR (95% CI)‡ | Multivariable-adjusted OR (95% CI)§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (range) | 44 (30–64) | |||

| Age | ||||

| 30–39 | 80 (35) | 75 | 1 | 1 |

| 40–49 | 83 (37) | 84 | 1.7 (0.8, 3.9) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.4) |

| 50–64 | 64 (28) | 83 | 1.6 (0.7, 4.0) | 1.3 (0.5, 3.3) |

| Race | ||||

| White | 78 (35) | 80 | 1 | 1 |

| Black | 124 (55) | 83 | 1.3 (0.6, 2.8) | 1.8 (0.8, 1.5) |

| Other‖ | 22 (10) | 74 | 0.8 (0.2, 2.5) | 1.4 (0.4, 5.1) |

| Annual household income (US dollars) | ||||

| <$10,000 | 95 (46) | 80 | 1 | 1 |

| $10,000+ | 112 (54) | 84 | 1.2 (0.6, 2.6) | 1.4 (0.6, 3.2) |

| Education | ||||

| High school diploma, GED, or less | 132 (62) | 76 | 1 | 1 |

| Some college or more | 81 (38) | 88 | 2.3 (1.0, 5.2) | 2.4 (1.0, 5.5) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married or living with partner | 59 (28) | 71 | 1 | 1 |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 66 (31) | 90 | 3.3 (1.1, 9.4) | 3.3 (1.1, 9.6) |

| Single, never married | 87 (41) | 79 | 1.5 (0.7, 3.5) | 1.7 (0.7, 3.9) |

| Urbanicity | ||||

| Urban | 47 (21) | 74 | 1 | 1 |

| Rural | 180 (79) | 83 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.3) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.4) |

| Current Smoking Status | ||||

| Smoker | 113 (51) | 85 | 1 | 1 |

| Non-smoker | 108 (49) | 78 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.3) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.3) |

| Internet use | ||||

| Daily | 91 (43) | 85 | 1 | 1 |

| Weekly | 43 (20) | 85 | 0.8 (0.3, 2.5) | 0.8 (0.3, 2.4) |

| Less often than weekly | 79 (37) | 79 | 0.6 (0.3, 1.4) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.5) |

| Religious preference | ||||

| No religion | 25 (14) | 96 | 6.6 (0.8, 53.6) | 5.8 (0.7, 49.7) |

| Baptist | 79 (43) | 78 | 1 | 1 |

| Christian, non-Baptist | 73 (39) | 84 | 1.5 (0.6, 3.6) | 1.5 (0.6, 3.7) |

| Other¶ | 8 (4) | 67 | 0.6 (0.1, 3.4) | 0.4 (0.1, 3.0) |

| Insurance | ||||

| None | 147 (68) | 80 | 1 | 1 |

| Medicaid | 51 (24) | 86 | 1.7 (0.6, 4.4) | 1.5 (0.6, 4.2) |

| Other | 19 (9) | 82 | 1.1 (0.3, 4.4) | 1.2 (0.3, 4.9) |

| Age at first intercourse (years) | ||||

| <16 | 64 (36) | 79 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥16 | 112 (64) | 80 | 1.0 (0.4, 2.3) | 0.8 (0.3, 2.0) |

| Number of live births | ||||

| 0–1 | 63 (29) | 81 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 60 (28) | 85 | 1.3 (0.5, 3.6) | 1.4 (0.5, 4.3) |

| 3+ | 94 (43) | 80 | 0.9 (0.4, 2.1) | 1.1 (0.4, 2.9) |

| Need help reading written health materials | ||||

| Never | 187 (85) | 81 | 1 | 1 |

| Rarely/sometimes/often/always | 33 (15) | 83 | 1.2 (0.4, 3.3) | 1.3 (0.4, 4.2) |

| Current contraception method | ||||

| None | 61 (37) | 80 | 1 | 1 |

| Permanent (tubal ligation/vasectomy) | 32 (19) | 73 | 0.7 (0.2, 1.9) | 0.6 (0.2, 1.9) |

| Non-permanent (condom/oral pill/IUD/injectable/withdrawal) | 36 (22) | 78 | 0.9 (0.3, 2.6) | 1.3 (0.4, 4.1) |

| Not needed (post-menopausal, no partner) | 38 (23) | 90 | 2.2 (0.6, 8.8) | 1.9 (0.4, 8.3) |

| Completely comfortable using tampon | ||||

| Yes | 117 (57) | 83 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 63 (31) | 83 | 1.0 (0.4, 2.5) | 1.1 (0.5, 2.8) |

| Never used | 24 (12) | 71 | 0.6 (0.2, 1.7) | 0.7 (0.2, 2.1) |

Abbreviations: GED, General Educational Development; IUD, intrauterine device

Numbers do not always add up to total due to missing values and/or skip patterns

Percentages may not add to 100% due to rounding

OR for positive thoughts vs neutral/mostly negative thoughts; ORs were adjusted for age (30–39; 40–49; 50–64)

ORs adjusted for age, (30–39; 40–49; 50–64), education (High school diploma, GED, or less; some college or more), and marital status (married or living with partner; divorced, separated, or widowed; single, never married)

Other includes Asian (n=2), American Indian/Alaska native (n=6), Hispanic (n=12), multiple race (n=2), Don't know (n=1)

Other includes Holiness (n=7) and Wiccan (n=1)

Overall, 81% of participants reported “mostly positive” thoughts about the home self-collection, and 17% reported “neutral” thoughts. Women with at least some college education were more likely to report positive thoughts than those with a high school diploma or less (88% vs. 76%; OR=2.4; 95% CI: 1.0, 5.5). Those who were divorced, separated, or widowed were more likely to report positive thoughts than those who were married or living with a partner (90% vs. 71%; OR=3.3; 95% CI: 1.1, 9.6). Positive thoughts about self-collection also appeared more common among women who reported not needing contraception (90%) compared to those currently using permanent contraception (73%), non-permanent contraception (78%), and those with a sexual partner but not currently using contraception (80%), though odds ratio estimates were relatively imprecise.

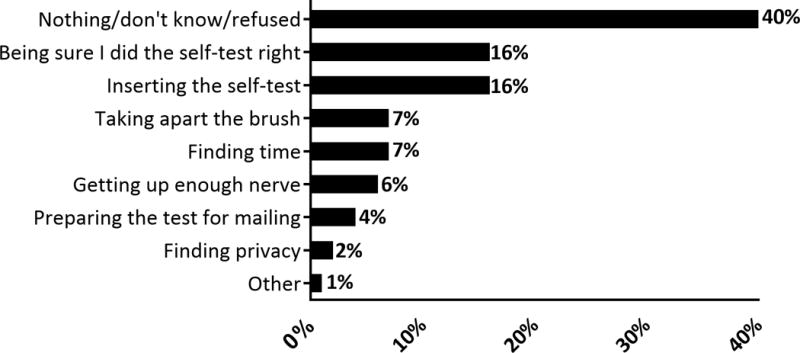

The most frequently reported positive attributes of the home self-collection included convenience (53%), ease of use (32%), and privacy (23%) (Table 2). Though most participants reported no dislikes (70%), 10% reported that the self-collection was uncomfortable, and 14% reported experiencing some difficulty in performing the self-collection. Examples of difficulties included removing the brush head from the handle, and spilling the liquid preservation media. When we framed the question to specifically elicit report of difficulties, “what would you say was the most difficult part about doing the self-test,” 120 participants named at least one difficulty. The most commonly reported difficulties were being sure they did the self-collection correctly (16%) and inserting the self-collection brush (16%) (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Reported acceptability of HPV self-testing among infrequently screened women in North Carolina (n=227)‡

| n* | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Likes/Dislikes/Preferences | ||

| Liked about self-test† | ||

| Convenience | 104 | 53 |

| Ease of use | 64 | 32 |

| Privacy | 46 | 23 |

| Doing it yourself | 35 | 18 |

| Comfort | 21 | 11 |

| General positive experience | 11 | 6 |

| Receiving results/getting Screened | 11 | 6 |

| Increased body awareness | 3 | 2 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 29 | |

| Disliked about self-test† | ||

| Nothing | 122 | 70 |

| Difficulties with performing test | 24 | 14 |

| Discomfort | 17 | 10 |

| Waiting for results | 8 | 5 |

| Sending by mail | 4 | 2 |

| Dislike of doing a vaginal test | 1 | 1 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 53 | |

| More convenient to use a self-test… | ||

| At home | 153 | 69 |

| At a medical clinic | 7 | 3 |

| They are about the same/no opinion | 61 | 28 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 6 | |

| More private to use a self-test… | ||

| At home | 182 | 82 |

| At a medical clinic | 2 | 1 |

| They are about the same | 38 | 17 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 5 | |

| Experiences/Attitudes | ||

| Ease of understanding the self-test instructions | ||

| Not hard | 215 | 99 |

| Somewhat/fairly/very hard | 2 | 1 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 10 | |

| Feel confident that used the self-test correctly | ||

| Strongly/somewhat agree | 213 | 97 |

| Somewhat/strongly disagree | 7 | 3 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 7 | |

| Emotions or feelings when using the self-test | ||

| Nothing | 102 | 55 |

| Anxious or worried/afraid or fearful/concerned about results | 37 | 20 |

| Empowered or confident/comfortable/Positive | 29 | 16 |

| Intimidated/overwhelmed/awkward | 7 | 4 |

| Relieved/surprised | 5 | 3 |

| Curious | 4 | 2 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 43 | |

| Willing to use the HPV self-test again‡ | ||

| Yes | 94 | 98 |

| No | 2 | 2 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 10 | |

| Willing to pay for the self-test | ||

| Would not pay | 18 | 9 |

| $0-$24 | 87 | 43 |

| $25+ | 98 | 48 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 24 | |

| Receiving the kit/returning the sample | ||

| Comfortable receiving the kit in the mail | ||

| Yes | 210 | 99 |

| No | 3 | 1 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 14 | |

| Preferred method for receiving the kit | ||

| In the mail | 107 | 51 |

| In a health clinic | 6 | 3 |

| In a pharmacy | 3 | 1 |

| Doesn’t matter/don’t know | 94 | 45 |

| Refused/missing | 17 | |

| Uncomfortable sending back the sample in the mail | ||

| Yes | 38 | 18 |

| No | 172 | 82 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 17 | |

| Concerned sample would get into the wrong hands (be seen or received by the wrong person) | ||

| Strongly/somewhat agree | 37 | 18 |

| Somewhat/strongly disagree | 170 | 82 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 20 | |

| Comfortable receiving self-test results by phone | ||

| Strongly/somewhat agree | 203 | 97 |

| Somewhat/strongly disagree | 6 | 3 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 18 | |

| Suggestions to improve self-test | ||

| Advice to make the self-test instructions better | ||

| No advice | 158 | 88 |

| Have a video | 8 | 4 |

| More detailed | 5 | 3 |

| Use simpler language | 4 | 2 |

| Shorter | 2 | 1 |

| Better Spanish translation | 1 | 1 |

| In-person assistance | 1 | 1 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 48 | |

| Suggestions for improving the self-collection brush | ||

| None | 130 | 73 |

| Make softer/swab instead of brush | 30 | 17 |

| Make easier to detach brush and insert into tube | 8 | 4 |

| Include mark of how far to insert | 3 | 2 |

| Make longer | 2 | 1 |

| Make curved | 2 | 1 |

| Make bristles bigger | 1 | 1 |

| Other | 4 | 2 |

| Refused/don’t know/missing | 48 |

Numbers do not always add up to total due to missing values and/or skip patterns

Percentages may add up to move than 100% given that participants could give multiple answers

From the follow-up questionnaire

Figure 1.

Reported difficulties with performing the HPV self-collection among 201 women who reported difficulties when asked: “What would you say was the most difficult part about doing the self-test?” Women who did not respond to the difficulties question are excluded (N=26). Percentages may not add to 100% because multiple responses were allowed.

Most participants were willing to perform HPV self-collection again (98%) and pay for the self-collection (91%). Almost all reported that the self-collection instructions were not hard to understand (99%) and were confident that they performed the self-collection correctly (97%). Only three women (1%) reported calling the study hotline to request help with performing the self-collection.

Nearly all women were comfortable receiving the kit in the mail (99%). As to their preferred method for receiving the self-collection kit, 51% preferred the mail to a clinic or pharmacy, and 45% reported no preference. Most expressed that it would be more convenient (69%) and more private (82%) to perform the self-collection at home, rather than at a medical clinic. A small proportion reported discomfort with sending the sample back in the mail (18%) or expressed some degree of concern that their sample would “get into the wrong hands (be seen or received by the wrong person) (18%).

Few women provided advice for improving the self-collection instructions, although having a video was the most common suggestion (4%). The most frequent suggestion for improving the self-collection brush included making it softer or using a swab instead of a brush (17%).

DISCUSSION

This study is among the first to evaluate the acceptability and ease of use of mailed HPV self-collection specifically among low-income U. S. women overdue for cervical cancer screening. It demonstrates that mailed HPV self-collection is highly acceptable in this high-priority group. Nearly all participants who completed self-collection were willing to perform the self-collection again (98%) and most said that self-collection was more private (82%) and convenient (69%) when used at home than in a medical clinic. Almost all were comfortable receiving the self-collection kit in the mail. However, some participants reported some difficulty, such as being sure the self-collection was done correctly or difficulty inserting the self-collection brush.

Strengths of our study include the focus on low-income, underscreened women with eligibility criteria that allowed for diversity with respect to demographic characteristics and geographic location within North Carolina. Additionally, our approach involved the use of mail for the distribution and return of kits, which has a good potential for scalability. Participants completed self-collection according to illustrated instructions that almost all reported were easy to understand, which is key for a model in which women complete the self-collection at home.

Our study also has limitations. We recruited a convenience sample of women; participants who chose to enroll may have had preconceived positive attitudes toward screening and health conscious behaviours. However, all women in this study were overdue for Pap testing, and therefore a primary target population for at-home HPV self-collection. Other limitations are the moderate return rate of the self-collected sample and relatively low completion of the acceptability questionnaire among those who did not return a self-collected sample.32 Odds ratios estimates for overall positive thoughts about the HPV self-collection should be interpreted with caution given relatively wide confidence intervals due to relatively small sample sizes, although they can be used to begin to understand differences in groups. Overall, our findings regarding difficulties and dislikes among women who did return a self-collected sample may inform future efforts to improve rates of participation and sample return.

Our findings of high acceptability are consistent with those described in a recent systematic review of the acceptability of HPV self-collection in 37 studies from 24 countries.16 They are also in accordance with other studies using HPV self-collection specifically among underscreened women in the U.S., most of which have provided kits personally in a community setting and have targeted specific ethnic groups.17, 21 In a study of Mexican immigrant women in Texas who had not received a Pap test in the preceding three years, nearly all participants (99%) reported willingness to perform HPV self-collection on a regular basis for cervical cancer screening.21 Moreover, the majority indicated that self-collection was more convenient and less stressful than in-clinic Pap testing. Another study among underscreened Haitian and Latina women in Miami reported that 97% found the self-test easy to use and would use it again.17 A unique characteristic of our study is that it focused on underscreened women without narrowing to a particular demographic group. In our sample, positive thoughts about self-collection were common overall and were largely similar across demographic and other characteristics. However, our results suggested somewhat higher acceptability among women with more education and those who were separated, widowed, or divorced.

While overall acceptability was high in our sample, some participants did report difficulty with the self-collection when prompted. The most commonly reported difficulties on the open-ended questions were uncertainty that the self-collection was done correctly, and problems inserting the self-collection brush. Other acceptability studies have similarly reported participant uncertainty about performing self-collection correctly.31, 35 For example, a prior study using home-based HPV self-testing reported that 57% of participants were not sure that they performed the self-collection correctly.31 However, in our study, responses to closed-ended questions provided some reassurance about women’s confidence in performing the self-collection. Overall, 97% of women in our sample strongly or somewhat agreed with the statement, “I am confident that I used the self-test correctly.” Nevertheless, future self-sampling screening programs could benefit from exploring ways to assure women they had completed the self-collection correctly.

It is notable that nearly all women in the current study were comfortable with receiving the self-collection kit in the mail (99%) and only 4% indicated a preference for receiving the kit in a health clinic or a pharmacy rather than in the mail. These findings suggest that mail may be an acceptable method of reaching infrequently screened women. To our knowledge, only two prior U.S. studies have used mail delivery of self-collection kits, with similarly promising findings regarding overall acceptability of this approach. In a study of Minnesota women aged 21–30 who were recruited via the internet, most participants who returned a self-collected sample by mail found the self-collection process to be easy (87%) and private (86%).31 A study among American Indian women, in which participants had the option to receive and return an HPV self-collection kit by mail, reported that 96% found the self-collection kit easy to use, and 62% preferred self-collection to Pap testing performed by a doctor or nurse.18 However, neither of these studies specifically targeted low-income, underscreened women, and neither queried participants’ comfort with the use of mail for receipt and return of the self-collection kit. In our study, roughly twenty percent of participants expressed discomfort with returning their sample by mail, with a similar proportion expressing concern that their sample could be seen or received by the wrong person. It is possible that incorporating simple measures, such as using certified mail for sample return or allowing self-sample return directly to a clinic or pharmacy, could alleviate these fears, thereby improving screening rates in programs that use mailed HPV self-collection kits.

CONCLUSIONS

Overall, our results support the conclusion that self-collection for HPV may be acceptable among low-income, underscreened women in the U.S. Most women in our study were comfortable receiving their self-collection kit and returning their sample by mail, supporting the use of mailed HPV self-collection to increase access to cervical cancer screening for this high-risk population. Future research could expand on our findings by conducting interviews with women who did not return a sample to identify strategies for increasing self-collection completion rates.

Supplementary Material

KEY MESSAGES.

Home-based self-collection of cervico-vaginal samples for HPV testing is a promising approach that may alleviate common barriers to clinic-based cervical cancer screening.

Most low-income, underscreened women reported an overall positive experience with home-based HPV self-collection.

Nearly all participants were willing to perform self-collection again, and most reported that self-collection was more private and convenient at home than in a clinic.

HPV self-collection is a highly acceptable screening method among low-income, underscreened women, and may increase access to cervical cancer screening in this high-risk population.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank Allen Rinas for his contributions to study design; Meredith Kamradt, Rachel Larsen, Kristen Ricchetti, Kelly Murphy, Stephanie Zentz, and Sara B. Smith for their work on study logistics, database, and recruitment; and Florence Paillard for her assistance editing the manuscript. We also thank Meindert Zwartz at Rovers Medical Devices for contributing the Viba self-collection brushes, and Belinda Yen-Lieberman and Jerome Belison at The Cleveland Clinic for conducting the HPV testing. QIAGEN donated kits for Hybrid Capture 2 HPV testing. This research was supported by Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust. Additional support for staff time came from the NCCU-LCCC Partnership in Cancer Research (5 U54 CA156733), and NIH NCI R01 CA183891.

Footnotes

AUTHOR DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

Dr. Jennifer S. Smith has received research grants and consultancies from Hologic, Becton Dickenson Corporation, and Trovagene over the past five years.

Author Contributions: JSS and NTB conceptualized and designed the study. CA analyzed the data. CA, ADM, and JSS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2017. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leyden WA, Manos MM, Geiger AM, et al. Cervical cancer in women with comprehensive health care access: attributable factors in the screening process. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97(9):675–83. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspscerv.htm. Updated June 2012. Accessed May 15, 2014.

- 4.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first human papillomavirus test for primary cervical cancer screening. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm394773.htm.

- 5.Akers AY, Newmann SJ, Smith JS. Factors underlying disparities in cervical cancer incidence, screening, and treatment in the United States. Curr Probl Cancer. 2007;31(3):157–81. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ackerson K, Gretebeck K. Factors influencing cancer screening practices of underserved women. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2007;19(11):591–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2007.00268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dzuba IG, Diaz EY, Allen B, et al. The acceptability of self-collected samples for HPV testing vs. the pap test as alternatives in cervical cancer screening. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11(3):265–75. doi: 10.1089/152460902753668466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wikstrom I, Lindell M, Sanner K, et al. Self-sampling and HPV testing or ordinary Pap-smear in women not regularly attending screening: a randomised study. Br J Cancer. 2011;105(3):337–9. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giorgi Rossi P, Marsili LM, Camilloni L, et al. The effect of self-sampled HPV testing on participation to cervical cancer screening in Italy: a randomised controlled trial (ISRCTN96071600) Br J Cancer. 2011;104(2):248–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6606040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gok M, van Kemenade FJ, Heideman DA, et al. Experience with high-risk human papillomavirus testing on vaginal brush-based self-samples of non-attendees of the cervical screening program. Int J Cancer. 2012;130(5):1128–35. doi: 10.1002/ijc.26128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gok M, Heideman DA, van Kemenade FJ, et al. HPV testing on self collected cervicovaginal lavage specimens as screening method for women who do not attend cervical screening: cohort study. Bmj. 2010;340:c1040. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Virtanen A, Anttila A, Luostarinen T, et al. Self-sampling versus reminder letter: effects on cervical cancer screening attendance and coverage in Finland. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(11):2681–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanner K, Wikstrom I, Strand A, et al. Self-sampling of the vaginal fluid at home combined with high-risk HPV testing. Br J Cancer. 2009;101(5):871–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bais AG, van Kemenade FJ, Berkhof J, et al. Human papillomavirus testing on self-sampled cervicovaginal brushes: an effective alternative to protect nonresponders in cervical screening programs. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(7):1505–10. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Snijders PJ, Verhoef VM, Arbyn M, et al. High-risk HPV testing on self-sampled versus clinician-collected specimens: a review on the clinical accuracy and impact on population attendance in cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(10):2223–36. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nelson EJ, Maynard BR, Loux T, et al. The acceptability of self-sampled screening for HPV DNA: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(1):56–61. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2016-052609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ilangovan K, Kobetz E, Koru-Sengul T, et al. Acceptability and Feasibility of Human Papilloma Virus Self-Sampling for Cervical Cancer Screening. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2016 doi: 10.1089/jwh.2015.5469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Winer RL, Gonzales AA, Noonan CJ, et al. Assessing Acceptability of Self-Sampling Kits, Prevalence, and Risk Factors for Human Papillomavirus Infection in American Indian Women. J Community Health. 2016;41(5):1049–61. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0189-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sewali B, Okuyemi KS, Askhir A, et al. Cervical cancer screening with clinic-based Pap test versus home HPV test among Somali immigrant women in Minnesota: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Cancer Med. 2015;4(4):620–31. doi: 10.1002/cam4.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Penaranda E, Molokwu J, Hernandez I, et al. Attitudes toward self-sampling for cervical cancer screening among primary care attendees living on the US-Mexico border. South Med J. 2014;107(7):426–32. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Montealegre JR, Mullen PD, M LJ-W, et al. Feasibility of Cervical Cancer Screening Utilizing Self-sample Human Papillomavirus Testing Among Mexican Immigrant Women in Harris County, Texas: A Pilot Study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(3):704–12. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0125-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scarinci IC, Litton AG, Garces-Palacio IC, et al. Acceptability and usability of self-collected sampling for HPV testing among African-American women living in the Mississippi Delta. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(2):e123–30. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barbee L, Kobetz E, Menard J, et al. Assessing the acceptability of self-sampling for HPV among Haitian immigrant women: CBPR in action. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(3):421–31. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9474-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.De Alba I, Anton-Culver H, Hubbell FA, et al. Self-sampling for human papillomavirus in a community setting: feasibility in Hispanic women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(8):2163–8. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harper DM, Noll WW, Belloni DR, et al. Randomized clinical trial of PCR-determined human papillomavirus detection methods: self-sampling versus clinician-directed–biologic concordance and women’s preferences. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(3):365–73. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones HE, Brudney K, Sawo DJ, et al. The acceptability of a self-lavaging device compared to pelvic examination for cervical cancer screening among low-income women. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2012;21(12):1275–81. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castle PE, Rausa A, Walls T, et al. Comparative community outreach to increase cervical cancer screening in the Mississippi Delta. Prev Med. 2011;52(6):452–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy J, Mark H, Anderson J, et al. A Randomized Trial of Human Papillomavirus Self-Sampling as an Intervention to Promote Cervical Cancer Screening Among Women With HIV. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20(2):139–44. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0000000000000195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crosby RA, Hagensee ME, Vanderpool R, et al. Community-Based Screening for Cervical Cancer: A Feasibility Study of Rural Appalachian Women. Sex Transm Dis. 2015;42(11):607–11. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Washington DC: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF); 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson EJ, Hughes J, Oakes JM, et al. Human Papillomavirus Infection in Women Who Submit Self-collected Vaginal Swabs After Internet Recruitment. J Community Health. 2015;40(3):379–86. doi: 10.1007/s10900-014-9948-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith JS, Des Marais AC, Deal A, Richman AR, Perez-Heydrich C, Yen-Lieberman B, Barclay L, Belinson JL, Brewer NT. Mailed HPV self-collection with Pap Test Referral for Infrequently Screened Women in the United States. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000681. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Castle PE, Sadorra M, Garcia FA, et al. Mouthwash as a low-cost and safe specimen transport medium for human papillomavirus DNA testing of cervicovaginal specimens. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16(4):840–3. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.American Sexual Health Association (ASHA) Who we are. Available from: http://www.ashasexualhealth.org/who-we-are/

- 35.Anhang R, Nelson JA, Telerant R, et al. Acceptability of self-collection of specimens for HPV DNA testing in an urban population. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2005;14(8):721–8. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2005.14.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.