Abstract

This cohort study examines the behavior and outcomes of deficient DNA mismatch repair in patients at elevated risk for malignant neoplasms, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

DNA mismatch repair status is a well-established biomarker in colorectal cancer and is associated with both a favorable prognosis and excellent response to immunotherapy. However, the influence of deficient DNA mismatch repair (dMMR) and microsatellite instability in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) remains unknown. The prognosis of PDAC is typically dismal and treatment options are limited, but previous research has suggested that microsatellite instability in resected PDAC specimens may be associated with improved survival. Because patients with Lynch syndrome harbor germline defects in mismatch repair genes and have significantly elevated lifetime risks of malignant neoplasms, including PDAC, we used this unique patient cohort to establish the clinical behavior and outcomes of dMMR PDAC.

Methods

The prospectively maintained Familial High-Risk Gastrointestinal Cancer Clinic and Genetic Counseling databases were queried to identify all patients with PDAC who were evaluated at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center from January 1, 2006, to December 31, 2016. Patients whose tumors showed evidence of dMMR by results of immunohistochemical analysis and/or who carry germline mutations in MLH1 (GenBank NG_007109), MSH2 (GenBank NG_007110), MSH6 (GenBank NG_007111), or PMS2 (GenBank NG_008466) were included. Clinicopathologic and genetic features as well as long-term follow-up were reviewed.

The MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective study and waived the individual informed consent requirement.

Results

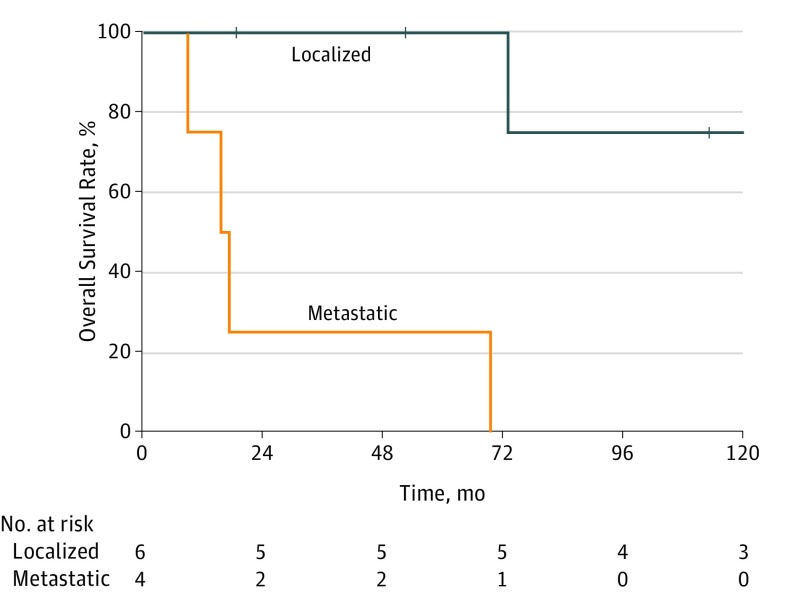

Among 821 patients included in the registry, 10 (1.2%) patients with PDAC were identified (Table). Seven patients had pathogenic germline mutations in MLH1 (n = 4) and MSH2 (n = 3). The mean (SD) age of all patients was 57.2 (15.0) years, 7 patients were men, and 8 had a personal history of Lynch syndrome–associated cancers. Six patients presented with localized disease and underwent either pancreatoduodenectomy (n = 4) or distal pancreatectomy (n = 2) with curative intent. Among these 6 patients, adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy was delivered to 3 and chemoradiotherapy was provided to 2. The 5-year overall survival rate of these patients was 100% after a median follow-up of 93.1 months (95% CI, 52.5-201.7). Four patients who presented with metastatic disease and were treated with systemic chemotherapy alone had a median overall survival of 16.5 months (95% CI, 7.2-24.0) and a 5-year overall survival rate of 25% (Figure).

Table. Complete Clinical, Genetic, and Outcomes Information for Patients With Mismatch Repair Deficient Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma.

| Age, y/Sex | Personal History of Other Malignant Neoplasms | PDAC Staging | Treatment | Outcome | Tumor IHC Loss of Expression | MSI | Germline Testing Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 70s/M | Sebaceous adenoma | pT3N1M0 | Distal pancreatectomy, adjuvant gemcitabine hydrochloride/capecitabine, vaccine trial | Retroperitoneal recurrence (26 mo); 113.4 mo alivea | MSH2, MSH6 | NA | MSH2 A636P (1906G>C) |

| 70s/M | Rectal cancer (twice), colon cancer, sebaceous adenoma, small bowel lymphoma | ypT3N0M0 | Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (gemcitabine), Whipple procedure | Died of other causes; 72.8 mo survival | MLH1, PMS2b | NA | MLH1 (c.1731G>A) |

| 40s/M | Sebaceous adenoma, colon cancer (twice) | Unknown | Whipple procedure | No evidence of disease; 334.6 mo alive | MLH1, PMS2b | Highb | MLH1 (deletion exon 16) |

| 20s/F | None | TxNxM0 | Whipple procedure | Retroperitoneal recurrence (69 mo)c; 201.8 mo survival | Not tested | NA | MLH1 (R265C) |

| 40s/M | Colon cancer | pT1N0M0 | Distal pancreatectomy, adjuvant gemcitabine | No evidence of disease; 18.6 mo alive | MLH1, PMS2 | NA | MLH1 (deletion exon 1-3) |

| 50s/F | Endometrial cancer | TxNxM1 | Gemcitabine/capecitabine | Died of disease; 15.6 mo survival |

MSH2b | NA | MSH2 R117X (c.2131C>T) |

| 50s/M | Sebaceous adenoma, duodenal cancer | TxNxM1 | Gemcitabine-abraxane | Died of disease; 8.9 mo survival | MSH2, MSH6b | Highb | MSH2 (c.2005 + 2dupT) |

| 50s/F | Breast cancer, ovarian cancer | TxNxM1 | Gemcitabine-cisplatin | Died of disease; 69.4 mo survival | MSH2, MSH6 | NA | Uninformative negative |

| 70s/M | Colon cancer | ypT3N0M0 | Neoadjuvant FOLFIRINOX and chemoradiotherapy (gemcitabine), Whipple procedure | No evidence of disease; 52.5 mo alive | MSH2, MSH6b | Highb | Uninformative negative |

| 60s/M | None | T4N1M1 | FOLFIRINOX, gemcitabine-abraxane | Died of disease; 17.5 mo survival | MLH1, PMS2 | NA | Uninformative negative |

Abbreviations: FOLFIRINOX, fluorouracil, leucovorin calcium, irinotecan hydrochloride, and oxaliplatin; IHC, immunohistochemistry; MSI, microsatellite instability; NA, not applicable.

Slowly progressive retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy; initially observed and then treated with chemotherapy (gemcitabine/capecitabine) followed by chemoradiotherapy (50 Gy in 25 fractions with concurrent capecitabine).

Tested on prior Lynch syndrome–associated tumor.

Retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy treated with chemotherapy (gemcitabine, oxaliplatin, bevacizumab) followed by chemoradiotherapy (50.4 Gy in 28 fractions with capecitabine).

Figure. Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Mismatch Repair Deficient Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma.

Six patients had localized disease and 4 patients had metastatic disease.

Discussion

In this single-institution study of dMMR PDAC, we identified patients with defects in MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 genes due to both germline and sporadic causes. Although patients with dMMR were not immune to nodal and distant metastases, those with localized disease who underwent surgery with curative intent had remarkably good outcomes with a 5-year overall survival rate of 100%, which is significantly better than the 25% reported in the largest randomized clinical trial of surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients who presented with metastatic disease also experienced better-than-expected outcomes, achieving a median of 16.5 months’ survival with one 5-year survivor (95% CI, 7.2-24.0) compared with a median of 11.1 months in patients treated with FOLFIRINOX (fluorouracil, leucovorin calcium, irinotecan hydrochloride, and oxaliplatin) and 6.8 months in patients treated with gemcitabine hydrochloride. These findings confirm those of previous studies, which suggested superior outcomes in patients with dMMR malignant neoplasms, presumably related to a more robust tumor-infiltrating immune response.

The limitation of this study is its retrospective, single-institution design and the inclusion of only patients referred to and evaluated in our familial and high-risk cancer clinic, but these findings have several implications. First, the diagnosis of PDAC in patients with a personal history of Lynch syndrome–associated cancers should prompt dedicated tumor and germline genetic testing. Second, treatment decisions should be made in the context of these patients’ favorable tumor biological characteristics and life expectancy. In fact, 2 patients in this series underwent local therapy (surgery or chemoradiotherapy) for retroperitoneal recurrences and experienced durable responses. Finally, previous research in colorectal cancer has demonstrated the influence of dMMR status on sensitivity to specific treatments, including checkpoint inhibitors. Ongoing clinical trials in patients with PDAC and mutations in DNA damage-repair genes, such as BRCA, PALB2, ATM, and MMR, hold promise for more effective targeted treatment options. Given the clinical significance of the findings reported herein, routine screening of PDAC specimens for dMMR may be indicated and should be the focus of future investigations.

References

- 1.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. . PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509-2520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakata B, Wang YQ, Yashiro M, et al. . Prognostic value of microsatellite instability in resectable pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8(8):2536-2540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kastrinos F, Mukherjee B, Tayob N, et al. . Risk of pancreatic cancer in families with Lynch syndrome. JAMA. 2009;302(16):1790-1795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, et al. ; European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer . Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304(10):1073-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M, et al. ; Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer; PRODIGE Intergroup . FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(19):1817-1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Knudsen ES, O’Reilly EM, Brody JR, Witkiewicz AK. Genetic diversity of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and opportunities for precision medicine. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(1):48-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]