Abstract

This cohort study assesses the role of preventability in the definition of failure to rescue when reviewing surgical performance for trauma patients who died after emergency surgery.

Failure to rescue (FTR) is defined as death after a major complication and has been adopted as a measure of quality in surgical patients. Current definitions of FTR are limited because they do not account for the influence of preventability on mortality. The aim of this study was to examine the association of preventability with rates of FTR among patients with major trauma.

Methods

This 6-year, retrospective cohort study was performed at a university-affiliated level I trauma center. We identified all adult patients with neck, torso, and peripheral vascular injuries (n = 802) who were taken directly from the emergency department to the operating room for emergency surgery. Institutional review board approval and waiver for patient consent were obtained from the John F. Wolf, MD, Human Subjects Committee, Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute.

Patients whose outcomes were classified as FTR were compared with those in the non-FTR group. Variables analyzed were demographic characteristics, Injury Severity Score (higher scores indicate more severe injuries), Glasgow Coma Scale score (higher scores indicate less neurologic impairment), transfusion requirements, presence of a head injury, location of the injury (chest, abdomen, or extremity), toxicology screen results, insurance status, and hypotension on admission (defined as systolic blood pressure ≤90 mm Hg). Complications were categorized as either medical or surgical.

We then completed an in-depth analysis of divisional and departmental peer review proceedings to identify the final adjudication of FTR as preventable, potentially preventable, or not preventable. The Pearson χ2 test and a paired t test were performed for univariate analysis and a logistic regression for multivariate analysis using Stata, version 12.0 (StataCorp). P values were 1-sided, and statistical significance was defined as P < .05.

Results

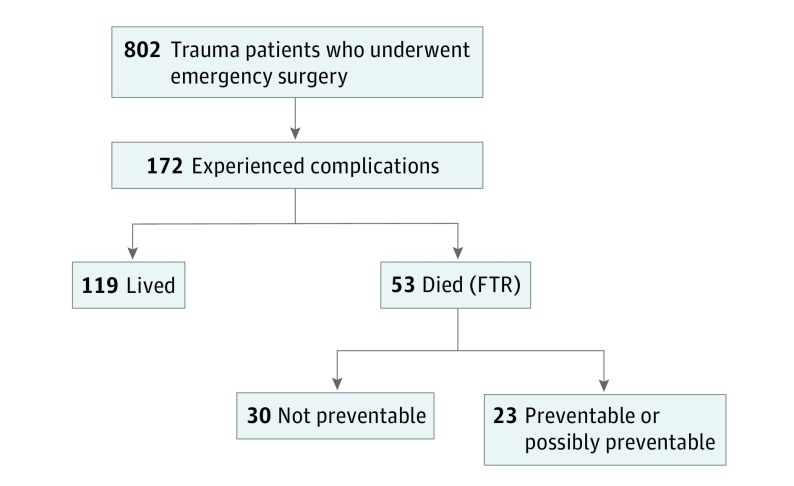

Of the 802 patients who underwent emergency surgery, 682 (85.0%) were men and 120 (15.0%) were women, with a mean (SD) age of 33.8 (14.7) years. Of these, 172 patients (21.4%) developed a complication. We found that 78 patients (45.4%) had a medical complication and 94 (54.6%) had a surgical complication.The most common complication was pneumonia (24 patients), and the incidence of FTR was 30.8% (53 patients). On univariate analysis, age, sex, and type of complication were similar between patients in the FTR and non-FTR groups. The FTR group had more patients with a blunt mechanism of injury, hypotension, a higher Injury Severity Score, a lower Glasgow Coma Scale score, and a shorter length of stay. Binary variables were assigned a value of 0 if the variable was absent and 1 if present. Variables with P < .20 were included in the multivariate analysis. On multivariate analysis, factors associated with FTR were insurance status (odds ratio [OR], 0.26; 95% CI, 0.09-0.73; P = .01), the presence of hypotension on admission to the emergency department (OR, 3.35; 95% CI, 1.35-8.30; P = .01), and higher Injury Severity Score (OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 1.03-1.11; P < .001) (Table). Only 9 deaths (17.0%) were adjudicated as being preventable, whereas 14 (26.4%) were potentially preventable and 30 (56.6%) were deemed not preventable. After adjustment for preventability, the FTR rate decreased significantly to 13.4% (23 of the 172 patients who experienced a complication after emergency surgery) (Figure).

Table. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated With Failure to Rescue.

| Factor | Risk of Failure to Rescue, OR (95% CI) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Insurance coverage | 0.26 (0.09-0.73) | .01 |

| Age per 1-y increase | 1.02 (0.99-1.05) | .14 |

| Penetrating mechanism of injury | 0.84 (0.33-2.12) | .71 |

| Hypotension on admission to EDa | 3.35 (1.35-8.30) | .01 |

| Higher Injury Severity Scoreb | 1.07 (1.03-1.11) | <.001 |

| Higher Glasgow Coma Scale score on admission to EDc | 0.95 (0.86-1.05) | .33 |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; FTR, failure to rescue; OR, odds ratio.

Defined as a systolic blood pressure of 90 mm Hg or lower.

Higher scores indicate more severe injuries.

Higher scores indicate less neurologic impairment.

Figure. Dispersion of Trauma Patients Who Underwent Emergency Surgery.

Preventable and possibly preventable cases represent only a few of the cases designated as failure to rescue (FTR).

Discussion

Failure to rescue has been used to assess quality of care. Its utility, however, is limited because of imprecise definitions and difficulty in collecting standardized data for comparison.

The current definition of FTR may be inadequate and overemphasizes variables beyond a trauma system’s control. This definition also classifies most nonpreventable deaths as FTR. This classification system leads to an inflated FTR rate that includes many cases in which no “failure” occurred. Incorporation of preventability into definitions of FTR may allow for more precise assessments of surgical performance.

Identifying the characteristics and risk factors in this more specific group may aid in the development of strategies to improve surgical care. In our cohort of all patients who developed a complication after emergency surgery (both preventable and not preventable), we found that 78 patients (45.4%) had a medical complication and 94 (54.6%) had a surgical complication. We have confirmed what others have reported in that lack of insurance is associated with higher rates of FTR. In addition, in our cohort, hypotension on admission to the emergency department and a higher Injury Severity Score were also associated with FTR.

Limitations of the study include the retrospective design, a patient cohort from a single institution, and the subjective nature of the determinations of preventability. In addition, some patients who died may have opted to forgo further treatment. Exclusion of those deaths from the preventable group would affect our results.

Future efforts to improve patient care should focus on preventable FTRs. This approach is now part of a national movement embraced by the American College of Surgeons, which has set a goal of zero preventable deaths from trauma.

References

- 1.Silber JH, Williams SV, Krakauer H, Schwartz JS. Hospital and patient characteristics associated with death after surgery: a study of adverse occurrence and failure to rescue. Med Care. 1992;30(7):615-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingraham AM, Greenberg CC. Failure to rescue and preventability: striving for the impossible? Surgery. 2017;161(3):793-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joseph B, Zangbar B, Khalil M, et al. Factors associated with failure-to-rescue in patients undergoing trauma laparotomy. Surgery. 2015;158(2):393-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jenkins DH, Winchell RJ, Coimbra R, et al. Position statement of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine Report, A National Trauma Care System: Integrating Military and Civilian Trauma Systems to Achieve Zero Preventable Deaths After Injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;81(5):819-823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]