Abstract

This study uses a nationally representative database to determine whether the incidence of emergency department visits for law enforcement increased relative to total emergency department visits from 2006 to 2012.

Deaths of civilians in contact with police have recently gained national public and policy attention. While journalists track police-involved deaths, epidemiologic data are incomplete, and trends in nonfatal injuries, which far outnumber deaths, are poorly understood. The International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification, includes external cause-of-injury codes identifying injuries owing to contact with law enforcement (E970-E978). Using these codes, prior studies have identified 715 118 nonfatal injuries, 3958 hospitalizations, and 3156 deaths between 2003 and 2011 from US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data and the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, and 55 400 fatal and nonfatal injuries in 2012 from the Vital Statistics mortality census, Nationwide Inpatient and Emergency Department Samples, and journalists’ reports. In this study, we used a nationally representative database to determine whether the incidence of emergency department (ED) visits for injures by law enforcement increased relative to total ED visits from 2006 to 2012. We assessed demographic and clinical characteristics of visits for law enforcement–associated injury.

Methods

The Nationwide Emergency Department Sample is a nationally representative sample of ED visits, both discharges and hospital admissions, including approximately 20% of US ED visits. We identified visits with an injury diagnosis and an E-code indicating legal intervention. We used the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample sampling strata and discharge weights to produce nationally representative estimates. We normalized counts to total ED visits and used the nonparametric test of trend to assess for trend over time. A P value of less than .05 was considered significant. All tests were 2-sided.

This study used a database that contained no individually identifiable information. Therefore, no patient consent was obtained, and the study met criteria to be exempt from review by the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine institutional review board.

Results

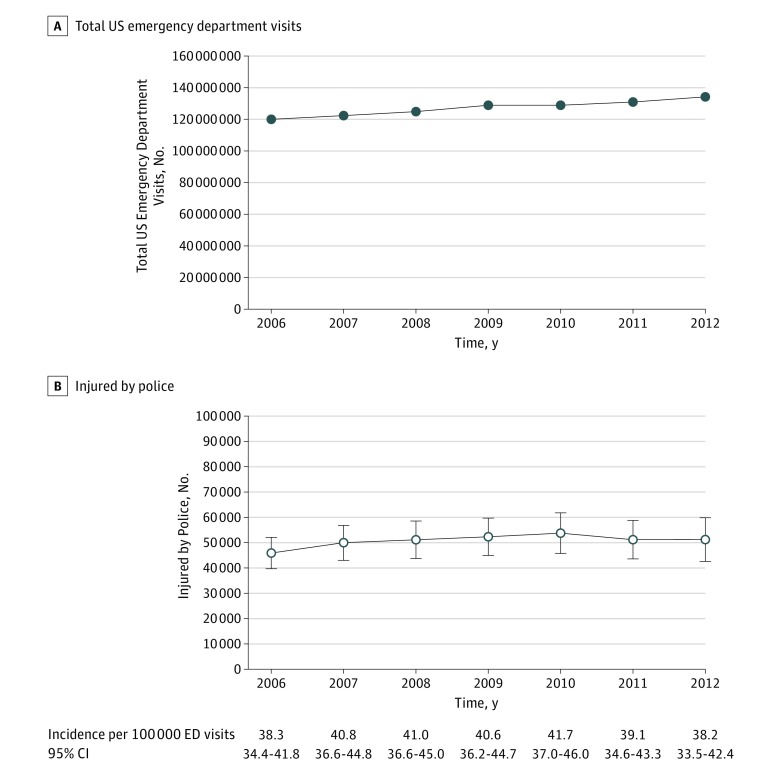

From 2006 to 2012, there were 355 677 ED visits for legal intervention injuries, and frequencies did not increase over time (linear trend −0.1; 95% CI, −0.9 to 0.6 per 100 000 ED visits; P = .61 for trend) (Figure). Just 0.3% of these visits (n = 1202) resulted in death. More than 80% of patients were men (n = 306 210), and the mean (SD) age of patients was 32.4 (0.1) years (Table). Most lived in zip codes with median household income less than the national average, and 81% lived in urban areas (n = 280 277). Legal intervention injuries were more common in the South and West and less common in the Northeast and Midwest. Most legal intervention injuries resulted from being struck, with gunshot and stab wounds accounting for fewer than 7%. Most injuries were minor (Injury Severity Score <9). Medically identified substance abuse was common in patients injured by police (9.7% [n = 34 343] for alcohol and 5.9% [n = 20 904] for other substances) as was mental illness (20.0%; n = 71 126).

Figure. Emergency Department Visits for Patients Injured by Police, 2006-2012.

Table. Characteristics of Police-Injured vs Assault-Injured Patients.

| Patient Characteristics | No. (%) (n = 355 600) |

|---|---|

| Women | 49 290 (13.9) |

| Age, mean (SD)a | 32.4 (0.1) |

| Weekend admission | 118 331 (33.3) |

| Region | |

| Northeast | 43 497 (17.2) |

| Midwest | 41 192 (16.3) |

| South | 83 899 (33.1) |

| West | 84 590 (33.4) |

| Insurance type | |

| Private | 68 544 (19.3) |

| Medicare | 15 681 (4.4) |

| Medicaid | 55 562 (15.6) |

| Uninsured/other | 215 889 (60.7) |

| Quartile of zip code median income | |

| 1 | 125 787 (37.2) |

| 2 | 88 144 (26.1) |

| 3 | 72 645 (21.5) |

| 4 | 51 217 (21.5) |

| Urban location | 280 277 (81.1) |

| Mechanism | |

| Gunshot wound | 13 291 (3.7) |

| Cut/stab wound | 11 258 (3.2) |

| Struck by or against | 276 400 (77.7) |

| Other or unspecified | 56 024 (15.8) |

| Hospital | |

| Metro nonteaching | 145 352 (40.9) |

| Metro teaching | 174 618 (49.1) |

| Rural | 35 706 (10.0) |

| Trauma center | 148 270 (41.7) |

| Injury Severity Score | |

| <9 | 346 848 (97.5) |

| 9-15 | 6564 (1.8) |

| 16-24 | 1667 (0.5) |

| ≥25 | 597 (0.2) |

| Diagnosed behavioral health comorbidities | |

| Alcohol intoxication, abuse or dependence | 34 343 (9.7) |

| Drug intoxication, abuse or dependence | 20 904 (5.9) |

| Developmental disability | 295 (0.1) |

| Other mental illness | 71 126 (20.0) |

| Admitted to the hospital | 15 038 (4.2) |

| Died in the emergency department | 834 (0.2) |

| Died during inpatient hospitalization | 368 (0.1) |

Discussion

Using a nationally representative data set, we identified approximately 51 000 ED visits per year for patients injured by law enforcement in the United States. While public attention has surged in recent years, we found these frequencies to be stable over 7 years, indicating that this has been a longer-term phenomenon. This analysis adds to existing literature by establishing frequencies of nonfatal injuries, which are most of the injuries, by assessing trends over time, and by including all ED visits, rather than the small proportion admitted to the hospital. While it is impossible to classify how many of these injuries are avoidable, these data can serve as a baseline to evaluate the outcomes of national and regional efforts to reduce law enforcement–related injury.

Inaccurate or incomplete coding is an inherent limitation of our study. Some patients have no cause of injury coded. There are no International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification codes for legal intervention injuries by fall or dog bite, although these may have been captured under E977, “legal intervention by unspecified means.” The Nationwide Emergency Department Sample does not include patient race/ethnicity or a geographic indicator finer than region. We cannot determine whether injuries occurred in custody or account for out-of-hospital deaths or readmissions. Existing databases, such as the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample, can be used for ongoing epidemiologic surveillance of this phenomenon. However, further study is needed to determine how new data collection efforts in the ED can add to the speed and accuracy of administrative data sources to support collaborative injury prevention efforts among clinicians, communities, law enforcement agencies, and policy makers.

References

- 1.Swaine J, Laughland O, Lartey J, et al. The counted: people killed by police in the United States: interactive. http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/ng-interactive/2015/jun/01/the-counted-police-killings-us-database. Accessed October 5, 2016.

- 2.Banks D, Couzens L, Blanton C, Cribb D Arrest-related deaths program assessment: technical Report NCJ 248543, RTI International. http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/lbrr/archives/cnmcs-plcng/cn33644-eng.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed January 2, 2017.

- 3.Barber C, Azrael D, Cohen A, et al. . Homicides by police: comparing counts from the national violent death reporting system, vital statistics, and supplementary homicide reports. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):922-927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang DC, Williams M, Sangji NF, Britt LD, Rogers SO Jr. Pattern of law enforcement-related injuries in the United States. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2016;80(6):870-876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller TR, Lawrence BA, Carlson NN, et al. . Perils of police action: a cautionary tale from US data sets. Inj Prev. 2017;23(1):27-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Overview NEDS. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp. Accessed October 5, 2016.