Key Points

Question

Does previous cesarean delivery increase the risk of reoperation, perioperative and postoperative complications, and blood transfusion when undergoing a benign hysterectomy later in life?

Findings

This registry-based cohort study of 7685 women indicates that women having a previous cesarean delivery are more likely to require reoperation and experience surgical complications after undergoing a benign hysterectomy compared with women having a previous vaginal birth.

Meaning

The increased risk of reoperation and complications related to hysterectomy later in life supports policies and clinical efforts to prevent cesarean deliveries that are not medically indicated.

Abstract

Importance

In recent decades, the global rates of cesarean delivery have rapidly increased. Nonetheless, the influence of cesarean deliveries on surgical complications later in life has been understudied.

Objective

To investigate whether previous cesarean delivery increases the risk of reoperation, perioperative and postoperative complications, and blood transfusion when undergoing a hysterectomy later in life.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This registry-based cohort study used data from Danish nationwide registers on all women who gave birth for the first time between January 1, 1993, and December 31, 2012, and underwent a benign, nongravid hysterectomy between January 1, 1996, and December 31, 2012. The dates of this analysis were February 1 to June 30, 2016.

Exposure

Cesarean delivery.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Reoperation, perioperative and postoperative complications, and blood transfusion within 30 days of a hysterectomy.

Results

Of the 7685 women (mean [SD] age, 40.0 [5.3] years) who met the inclusion criteria, 5267 (68.5%) had no previous cesarean delivery, 1694 (22.0%) had 1 cesarean delivery, and 724 (9.4%) had 2 or more cesarean deliveries. Among the 7685 included women, 3714 (48.3%) had an abdominal hysterectomy, 2513 (32.7%) had a vaginal hysterectomy, and 1458 (19.0%) had a laparoscopic hysterectomy. In total, 388 women (5.0%) had a reoperation within 30 days after a hysterectomy. Compared with women having vaginal deliveries, fully adjusted multivariable analysis showed that the adjusted odds ratio of reoperation for women having 1 previous cesarean delivery was 1.31 (95% CI, 1.03-1.68), and the adjusted odds ratio was 1.35 (95% CI, 0.96-1.91) for women having 2 or more cesarean deliveries. Perioperative and postoperative complications were reported in 934 women (12.2%) and were more frequent in women with previous cesarean deliveries, with adjusted odds ratios of 1.16 (95% CI, 0.98-1.37) for 1 cesarean delivery and 1.30 (95% CI, 1.02-1.65) for 2 or more cesarean deliveries. Blood transfusion was administered to 195 women (2.5%). Women having 2 or more cesarean deliveries had an adjusted odds ratio for receiving blood transfusion of 1.93 (95% CI, 1.21-3.07) compared with women having no previous cesarean delivery.

Conclusions and Relevance

Women with at least 1 previous cesarean delivery face an increased risk of complications when undergoing a hysterectomy later in life. The results support policies and clinical efforts to prevent cesarean deliveries that are not medically indicated.

This Danish registry-based cohort study investigates whether previous cesarean delivery increases the risk of reoperation and perioperative and postoperative complications when undergoing a hysterectomy later in life.

Introduction

Cesarean delivery is the most common major surgery performed in the world, and the rate is rapidly increasing. The global mean cesarean rate is estimated at 18.6%, and the 2010 rate in European countries ranged from 14.8% to 52.2%. In Denmark, the cesarean delivery rate is 21.4%. Cesarean deliveries aim to decrease maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality, but increased rates beyond 19.1% have not been associated with maternal or neonatal benefits. Instead, higher cesarean rates have been related to increased morbidity for mothers and neonates. Cesarean deliveries may be followed by perioperative and postoperative complications and are associated with immediate and long-term risks, including an increased risk of hysterectomy, blood transfusion, intensive care unit admission, wound infection, readmission, placenta previa, placenta accrete, and uterine rupture in future pregnancies. Independent of future pregnancies, cesarean deliveries are related to an increased risk of chronic pain and bowel obstruction due to adhesions. The adhesions can lead to difficulties in subsequent surgical procedures, heightening the risk of later surgical complications.

The high prevalence of hysterectomy later in life makes this procedure a useful proxy for investigating long-term surgical complications associated with previous cesarean delivery. In 2015, the prevalence of benign hysterectomy in Denmark was about 10%. Approximately 6000 hysterectomies are performed per year in Denmark, and 80% of these have a benign indication. The results of previous studies on the effect of cesarean deliveries on subsequent hysterectomies suggest that a prior cesarean delivery may be related to lower urinary tract injuries, increased intraoperative and postoperative blood transfusion, and readmission within 30 days of a hysterectomy. However, these studies are limited to single-institution investigations. To our knowledge, the population influence of long-term surgical complications from cesarean deliveries has not been evaluated using a nationwide cohort.

The aim of this study was to investigate the association of previous cesarean delivery with the risk of reoperation, surgical complications, and blood transfusion within 30 days after a hysterectomy later in life. We hypothesized that women with previous cesarean delivery may have an increased risk of reoperation and perioperative and postoperative complications when undergoing a benign hysterectomy. The Danish National Patient Registry provides a unique opportunity to perform a longitudinal study of patients over the course of their lives based on administrative data that include a wide range of relevant clinical and sociodemographic covariates.

Methods

In this registry-based study, we established a cohort that included all Danish women who gave birth for the first time between January 1, 1993, and December 31, 2012, and underwent a benign, nongravid hysterectomy between January 1, 1996, and December 31, 2012. The dates of this analysis were February 1 to June 30, 2016. Since 1968, all Danish residents have been assigned a personal identification number and registered in the Danish Civil Registration System. The personal identification number links all information about an individual across numerous nationwide registers. We aggregated data from the Danish National Patient Register, the Register of Medicinal Products Statistics, and the Income Statistics Register. Diagnoses are coded according to the World Health Organization’s International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision from 1994 onward and the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Eighth Revision before 1994. Surgical procedures are coded in the Danish National Patient Register using the Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedures from 1996 onward. Information about all medical prescriptions dispensed at Danish pharmacies is coded using the World Health Organization’s Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System.

The cohort was identified from the Danish National Patient Register using diagnosis codes for vaginal birth and surgery codes for cesarean delivery and total hysterectomy (eTable 1 in the Supplement). We included all women who had a hysterectomy after 1995, when the registries implemented the use of the Nordic Classification of Surgical Procedures codes, and had given birth after 1992, when the registries first specified mode of delivery. Because we cannot determine if women had a vaginal delivery or a cesarean delivery before 1992, we excluded all women with a delivery before this date. Furthermore, we excluded women who had a hysterectomy during the postpartum period, defined as 42 days or less after giving birth, and women who had a hysterectomy due to cancer in the female genital tract.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency. Retrospective studies using the Danish registries do not require individual informed consent. The study was carried out in the research environment in Statistics Denmark, a state organization that enables administrative registries to be combined for research, while keeping personally identifiable information encrypted.

Patient Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort were extracted from the Danish National Patient Register, including the following: age at the time of hysterectomy, parity, comorbidities (type 1 and type 2 diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, previous breast cancer or colon cancer, pelvic inflammatory disease, and endometriosis), previous abdominal surgery (intra-abdominal gynecological, abdominal, and urological surgical procedures), time between last delivery and hysterectomy, route of hysterectomy, and indication for hysterectomy. We divided parity into 1, 2, and more than 2 live births.

The route of hysterectomy was divided into the following 3 groups: abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic (including robotic) (eTable 1 in the Supplement). We calculated individual income during the year the woman had a hysterectomy as a proxy for her socioeconomic status. Individual income was calculated from the household income included in the Income Statistics Registry and was divided by 1.5 if the woman shared her household with another person to account for shared fixed expenditures. The income was indexed to 2009 to adjust for inflation, and women were stratified into quartiles according to their adjusted individual income.

We identified the hospitalization associated with the hysterectomy by admission and discharge dates on either side of the surgery date and obtained the indications for the hysterectomy from diagnosis codes from that hospitalization. More than one benign indication was possible.

Outcomes

The preselected primary outcome was reoperation within 30 days of a hysterectomy. All registered surgical codes relevant for reoperation within 30 days of the hysterectomy were detected and sorted (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The secondary outcomes were operative complications and blood transfusion within 30 days of the hysterectomy. We defined complications as bleeding or hematomas, infection, perioperative lesions, wound rupture and adhesions, acute cystitis, disorders of the genitourinary system, and deep vein thrombosis.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline comparison of categorical data was performed with χ2 tests and continuous data with analyses of variance. Correlations between patient characteristics and outcomes were examined with linear logistic regression models. The crude models contain the outcome and number of cesarean deliveries. The adjusted models controlled for age at the time of hysterectomy, individual income, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, breast cancer and colon cancer, previous abdominal surgery, time between last delivery and hysterectomy, and route of hysterectomy. The following interactions with cesarean delivery were selected before analysis: age at the time of hysterectomy, individual income, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, previous cancer, previous abdominal surgery, and route of hysterectomy. No interactions were significant. A sensitivity analysis was performed that excluded all women with previous abdominal surgery.

We used statistical software (SAS, version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc) for data management and another software package (R, version 3.2.2; R Core Team) for analyses. Statistical significance was determined by 2-sided P < .005.

Results

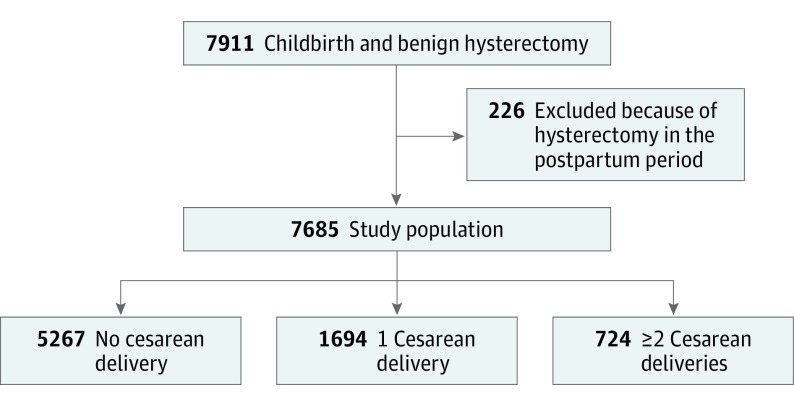

A flowchart of patient selection is shown in Figure 1. We included 7685 women who had a hysterectomy, of whom 5267 had no previous cesarean delivery, 1694 had 1 cesarean delivery, and 724 had 2 or more cesarean deliveries.

Figure 1. Flowchart of the Study Population.

The 3 groups according to the number of cesarean deliveries are shown.

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. The mean (SD) age at the time of hysterectomy was 40.0 (5.3) years. Women with 2 or more cesarean deliveries were younger at the time of hysterectomy, with mean (SD) ages of 38.2 (5.1) years compared with 40.2 (5.3) years for women with no previous cesarean delivery and 40.0 (5.3) years for women with 1 cesarean delivery (P < .001). Comorbidities were more frequent in the group of women with previous cesarean delivery compared with the group of women without cesarean delivery. Women with previous cesarean delivery were more likely to have a history of previous laparotomy for any indication at the time of hysterectomy. The group of women with 2 or more cesarean deliveries was also more likely to have a history of both laparoscopic surgery and laparotomy before the hysterectomy compared with the other 2 groups. A sensitivity analysis that excluded women who had previous abdominal surgery was performed, and only minor insignificant changes in odds ratios were noted.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics.

| Variable | No Cesarean Delivery (n = 5267) |

1 Cesarean Delivery (n = 1694) |

≥2 Cesarean Deliveries (n = 724) |

Total (N = 7685) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at the time of hysterectomy, mean (SD), y | 40.2 (5.3) | 40.0 (5.3) | 38.2 (5.1) | 40.0 (5.3) | <.001 |

| Parity, No. (%) | |||||

| 1 | 2413 (45.8) | 867 (51.2) | 0 | 3280 (42.7) | <.001 |

| 2 | 2188 (41.5) | 625 (36.9) | 489 (67.5) | 3302 (43.0) | |

| >2 | 666 (12.6) | 202 (11.9) | 235 (32.5) | 1103 (14.4) | |

| Individual income quartile, No. (%) | |||||

| 1 | 274 (5.2) | 80 (4.7) | 21 (2.9) | 375 (4.9) | .01 |

| 2 | 1088 (20.7) | 337 (19.9) | 140 (19.3) | 1565 (20.4) | |

| 3 | 1805 (34.3) | 645 (38.1) | 264 (36.5) | 2714 (35.3) | |

| 4 | 2093 (39.7) | 629 (37.1) | 298 (41.2) | 3020 (39.3) | |

| Missing | 7 | 3 | 1 | 11 | |

| Diabetes, No. (%) | |||||

| None | 5160 (98.0) | 1630 (96.2) | 679 (93.8) | 7469 (97.2) | <.001 |

| Diabetes | 107 (2.0) | 64 (3.8) | 45 (6.2) | 216 (2.8) | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, No. (%) | |||||

| None | 5225 (99.2) | 1676 (98.9) | 716 (98.9) | 7617 (99.1) | .48 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 42 (0.8) | 18 (1.1) | 8 (1.1) | 68 (0.9) | |

| Hypertension, No. (%) | |||||

| None | 4886 (92.8) | 1497 (88.4) | 651 (89.9) | 7034 (91.5) | <.001 |

| Hypertension | 381 (7.2) | 197 (11.6) | 73 (10.1) | 651 (8.5) | |

| Cardiovascular disease, No. (%) | |||||

| None | 5087 (96.6) | 1617 (95.5) | 682 (94.2) | 7386 (96.1) | .002 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 180 (3.4) | 77 (4.5) | 42 (5.8) | 299 (3.9) | |

| Previous cancer, No. (%) | |||||

| Breast cancer | 103 (2.0) | 26 (1.5) | 14 (1.9) | 143 (1.9) | .54 |

| Colon cancer | 13 (0.2) | 7 (0.4) | 1 (0.1) | 21 (0.3) | |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease, No. (%) | |||||

| None | 4668 (88.6) | 1458 (86.1) | 621 (85.8) | 6747 (87.8) | .004 |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | 599 (11.4) | 236 (13.9) | 103 (14.2) | 938 (12.2) | |

| Endometriosis, No. (%) | |||||

| None | 4569 (86.7) | 1399 (82.6) | 604 (83.4) | 6572 (85.5) | <.001 |

| Endometriosis | 698 (13.3) | 295 (17.4) | 120 (16.6) | 1113 (14.5) | |

| Previous abdominal surgery, No. (%) | |||||

| None | 3431 (65.1) | 979 (57.8) | 340 (47.0) | 4750 (61.8) | <.001 |

| Laparoscopy | 1432 (27.2) | 474 (28.0) | 173 (23.9) | 2079 (27.1) | |

| Laparotomy | 213 (4.0) | 143 (8.4) | 143 (19.8) | 499 (6.5) | |

| Both | 191 (3.6) | 98 (5.8) | 68 (9.4) | 357 (4.6) | |

| Time between last delivery and hysterectomy, mean (SD), y | 8.8 (4.4) | 7.8 (4.2) | 5.6 (3.6) | 8.3 (4.4) | <.001 |

| Route of hysterectomy, No. (%) | |||||

| Laparotomy | 2205 (41.9) | 1016 (60.0) | 493 (68.1) | 3714 (48.3) | <.001 |

| Vaginal | 2110 (40.1) | 330 (19.5) | 73 (10.1) | 2513 (32.7) | |

| Laparoscopic | 952 (18.1) | 348 (20.5) | 158 (21.8) | 1458 (19.0) | |

| Indication for hysterectomy, >1 possible, No. (%) | |||||

| Total | 7204 | 2303 | 949 | 10 456 | NA |

| Fibroids | 1875 (26.0) | 625 (27.1) | 211 (22.2) | 2711 (25.9) | <.001 |

| Menstrual disorder | 2803 (38.9) | 952 (41.3) | 464 (48.9) | 4219 (40.4) | <.001 |

| Prolapse or incontinence | 525 (7.3) | 62 (2.7) | 7 (0.7) | 594 (5.7) | <.001 |

| Endometriosis | 583 (8.1) | 244 (10.6) | 86 (9.1) | 913 (8.7) | .001 |

| Precancerous lesions | 634 (8.8) | 151 (6.6) | 60 (6.3) | 845 (8.1) | <.001 |

| Pain | 784 (10.9) | 269 (11.7) | 121 (12.8) | 1174 (11.2) | .32 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Among all women in the cohort, the route of hysterectomy was laparotomy in 3714 (48.3%), vaginal in 2513 (32.7%), and laparoscopic in 1458 (19.0%). The risk of laparotomy was higher for women with 1 cesarean delivery and highest for women with 2 or more cesarean deliveries. Vaginal hysterectomies were more common in the group with no previous cesarean delivery (2110 [40.1%]) compared with the group with 1 cesarean delivery (330 [19.5%]) and the group with 2 or more cesarean deliveries (73 [10.1%]) (P < .001). Laparoscopic hysterectomy was more evenly distributed across the 3 groups, accounting for approximately 20% of the hysterectomies in each group (Table 1).

The indications for hysterectomy (10 456 in total) included fibroids (2711 [25.9%]), menstrual disorder (eg, menorrhea, metrorrhagia, or polyps) (4219 [40.4%]), prolapse or incontinence (594 [5.7%]), endometriosis (913 [8.7%]), precancerous lesions (845 [8.1%]), and pain (eg, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, or abdominal or pelvic pain) (1174 [11.2%]). Menstrual disorder was a more common indication in the groups with 1 and 2 or more cesarean deliveries, while prolapse or incontinence was a more common indication for women with no previous cesarean delivery.

Reoperation

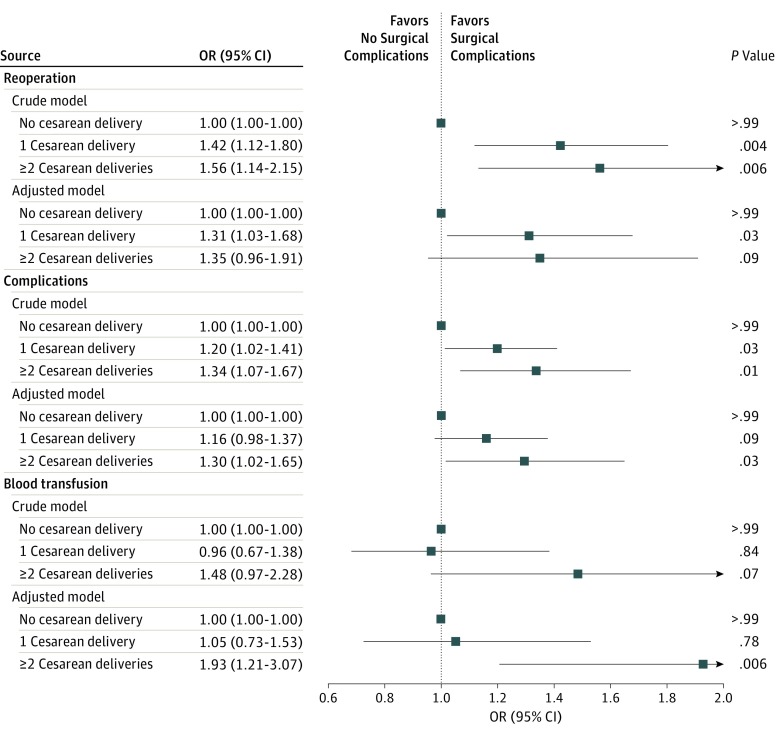

Overall, 5.0% (n = 388) of women had a reoperation within 30 days after a hysterectomy. The risk of reoperation increased with the number of previous cesarean deliveries, with a frequency of 4.4% (n = 234) for women with no previous cesarean delivery compared with 6.2% (n = 105) for women with 1 cesarean delivery and 6.8% (n = 49) for women with 2 or more cesarean deliveries (Table 2). Figure 2 shows the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios for reoperation dependent on the number of cesarean deliveries. Fully adjusted multivariable analysis showed that women with 1 cesarean delivery had an unadjusted odds ratio of 1.42 (95% CI, 1.12-1.80) and an adjusted odds ratio of 1.31 (95% CI, 1.03-1.68) for reoperation, while women with 2 or more cesarean deliveries had an unadjusted odds ratio of 1.56 (95% CI, 1.14-2.15) and an adjusted odds ratio of 1.35 (95% CI, 0.96-1.91) for reoperation.

Table 2. Outcomes.

| Variable | No Cesarean Delivery (n = 5267) |

1 Cesarean Delivery (n = 1694) |

≥2 Cesarean Deliveries (n = 724) |

Total (N = 7685) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reoperation, >1 Possible, No. (%) | |||||

| None | 5028 (95.5) | 1587 (93.7) | 674 (93.1) | 7289 (94.8) | NA |

| Reoperation | 234 (4.4) | 105 (6.2) | 49 (6.8) | 388 (5.0) | .001 |

| Total reoperations | 274 | 119 | 54 | 447 | NA |

| Gynecological procedures | 158 (57.7) | 72 (60.5) | 35 (64.8) | 265 (59.3) | .005 |

| Gastrointestinal procedures | 60 (21.9) | 27 (22.7) | 10 (18.5) | 97 (21.7) | .33 |

| Urological procedures | 32 (11.7) | 13 (10.9) | 6 (11.1) | 51 (11.4) | .65 |

| Other procedures | 24 (8.8) | 7 (5.9) | 3 (5.5) | 34 (7.6) | .88 |

| Complications, >1 Possible, No. (%) | |||||

| None | 4668 (88.6) | 1466 (86.5) | 617 (85.2) | 6751 (87.8) | NA |

| Complications | 599 (11.4) | 228 (13.5) | 107 (14.8) | 934 (12.2) | .006 |

| Total complications | 704 | 273 | 135 | 1112 | NA |

| Bleeding or hematomas | 354 (50.3) | 120 (44.0) | 61 (45.2) | 535 (48.1) | .23 |

| Infection | 162 (23.0) | 63 (23.1) | 25 (18.5) | 250 (22.5) | .41 |

| Perioperative lesions | 52 (7.4) | 28 (10.3) | 13 (9.6) | 93 (8.4) | .03 |

| Wound rupture and adhesions | 26 (3.7) | 17 (6.2) | 9 (6.7) | 52 (4.7) | .90 |

| Acute cystitis | 44 (6.3) | 23 (8.4) | 8 (5.9) | 75 (6.7) | .15 |

| Unspecified complications | 73 (10.4) | 30 (11.0) | 21 (15.6) | 124 (11.2) | .01 |

| Blood Transfusion, No. (%) | |||||

| None | 5138 (97.6) | 1654 (97.6) | 698 (96.4) | 7490 (97.5) | NA |

| Blood transfusion | 129 (2.4) | 40 (2.4) | 26 (3.6) | 195 (2.5) | .16 |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Figure 2. Odds Ratio (OR) and 95% CI of Outcomes.

The crude model is adjusted for the number of cesarean deliveries, and the adjusted model contains the following variables: cesarean delivery, age, individual income, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, breast cancer and colon cancer, previous abdominal surgery, and route of hysterectomy.

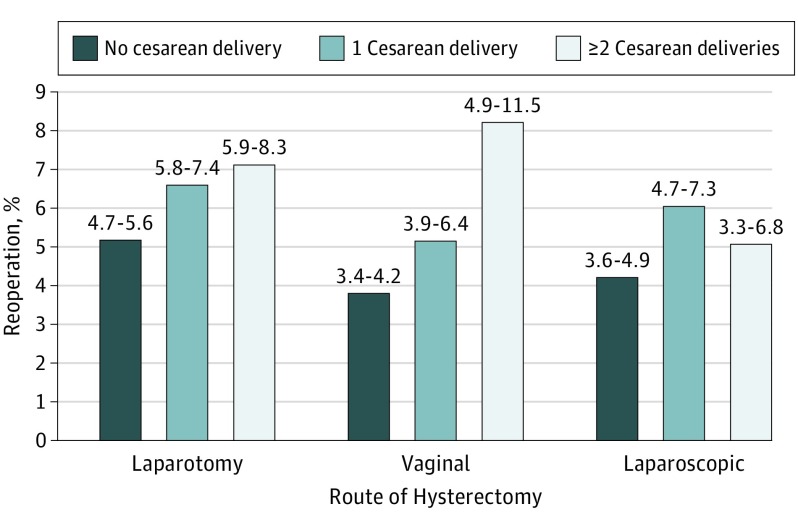

Compared with abdominal surgery, vaginal and laparoscopic routes of hysterectomy were associated with a decreased risk of reoperation, with adjusted odds ratios of 0.75 (95% CI, 0.58-0.96) for vaginal hysterectomy and 0.81 (95% CI, 0.61-1.08) for laparoscopic hysterectomy (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Statistical tests for interaction detected no interaction between the number of cesarean deliveries and the route of hysterectomy. Figure 3 shows the observed reoperation rates in the 3 groups according to the route of hysterectomy. Women with at least 1 cesarean delivery had an increased frequency of reoperation independent of the route of hysterectomy later in life.

Figure 3. Frequency and 95% CI of Reoperation.

Reoperation is shown according to the number of cesarean deliveries and the route of hysterectomy.

Among 447 total reoperations, gynecological procedures (265 [59.3%]) were the most common, followed by gastrointestinal procedures (97 [21.7%]), urological procedures (51 [11.4%]), and other procedures (34 [7.6%]) (Table 2). Gynecological procedures were more common for women with 2 or more cesarean deliveries (158 [57.7%] for no previous cesarean delivery, 72 [60.5%] for 1 cesarean delivery, and 35 [64.8%] for ≥2 cesarean deliveries) (P = .005), but there were no significant differences between the 3 groups for gastrointestinal procedures or urological procedures.

Perioperative and Postoperative Complications

Overall, 934 women (12.2%) experienced at least 1 surgical complication within 30 days of the hysterectomy. Bleeding was the most common complication, followed by infection and perioperative lesions (Table 2). Compared with women having no previous cesarean deliveries, women having 1 cesarean delivery had an odds ratio of 1.20 (95% CI, 1.02-1.41) and an adjusted odds ratio of 1.16 (95% CI, 0.98-1.37) for complications, and women having 2 or more cesarean deliveries had an odds ratio of 1.34 (95% CI, 1.07-1.67) and an adjusted odds ratio of 1.30 (95% CI, 1.02-1.65) for complications (Figure 2). Surgical complications were more likely for laparoscopic hysterectomy than for abdominal hysterectomy (adjusted odds ratio, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.59-0.83) and vaginal hysterectomy (adjusted odds ratio, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.57-0.84).

Blood Transfusion

Overall, 195 women (2.5%) received a blood transfusion (Table 2). Women with 2 or more cesarean deliveries had an increased risk of needing blood transfusion, with an odds ratio of 1.48 (95% CI, 0.97-2.28) and an adjusted odds ratio of 1.93 (95% CI, 1.21-3.07) compared with women having no previous cesarean delivery (Figure 2). Previous laparoscopic surgery and laparoscopic route of hysterectomy also increased the risk for blood transfusion, with adjusted odds ratios of 1.33 (95% CI, 0.96-1.82) and 1.70 (95% CI, 1.19-2.43), respectively (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Discussion

Our results show that previous cesarean delivery increases the risk of reoperation and perioperative and postoperative complications among women undergoing a benign hysterectomy later in life. Compared with women having only vaginal deliveries, women with 1 cesarean delivery had a 31.1% increased risk of reoperation after a hysterectomy, while women with 2 or more cesarean deliveries had a 38% increased risk of reoperation after a hysterectomy.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this investigation is the first population study of the association of cesarean delivery with hysterectomy complications. The use of nationwide registers allowed us to follow up all women in Denmark through different health care sectors, outpatient departments, and hospital admissions and to adjust for numerous potential confounders. Data from these registers have been found to hold detailed information of high validity, and data were collected independent of this study, thus reducing the risk of information bias. We were able to measure several specific surgical complications, such as bleeding, infection, and perioperative lesions. While previous investigations have examined hospital readmission rates, this measure was not included in the present study because many complications not requiring surgery are managed at outpatient clinics in Denmark; therefore, hospital readmission rates may underestimate the actual rates of complications after a hysterectomy.

Our study is limited by its observational design, which does not allow for elimination of all potential confounding factors; only known confounders can be adjusted for and only to the extent that they can be accurately measured and are available in the national registers. Therefore, residual confounding may persist. It should be noted that we did not have access to data on body mass index: a low or high body mass index increases the risk for surgical complications, such as bleeding and infection. However, we were able to control for obesity-associated factors, such as hypertension and diabetes. In addition, small-bowel obstruction, a common postoperative complication, was absent from our data set. This absence may have led to underreporting of the association of cesarean delivery with surgical complications after a hysterectomy later in life.

In our study, the registers limited our sample to women who gave birth after 1992 and had a hysterectomy after 1995. Therefore, we were only able to include women who had a hysterectomy within 19 years of their first birth. Our cohort is thus younger than the median age for benign hysterectomy in Denmark (40.0 years vs 48 years for all benign hysterectomies in Denmark in 2011). This limitation too may have led to underreporting of the association of cesarean delivery with surgical risks later in life. Furthermore, the Danish National Patient Register does not contain detailed information on the deliveries or the surgical procedures (ie, gestational age, use of medications, indication for cesarean delivery, operating time, hospital level, or complications that were treated by a general practitioner).

Interpretation

Our results indicate that women with previous cesarean delivery more frequently needed unplanned reoperation within 30 days of a hysterectomy. This effect may be due to the risk of intra-abdominal adhesions, which increases with the number of cesarean deliveries. The adhesions may complicate future surgery, leading to longer operating time and an increased risk of adverse events, which could result in reoperations. Besides the physical risks and emotional stress of having to undergo another operation, reoperations often are followed by treatment in intensive care units, which may induce anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress among the affected women.

The set of complications identified in our data aligns well with those reported by Lee et al as the indications for readmission after a benign hysterectomy in a tertiary care academic medical center in the United States. While our study showed a 16% to 29.6% increased risk of experiencing at least 1 complication among women with at least 1 previous cesarean delivery, Lee et al found that the risk for readmission was more than doubled. In both studies, bleeding and infection were the most common complications.

In our study population consisting of women with at least 1 childbirth and a benign hysterectomy, the cesarean delivery rate was 31.5% compared with 21% in the general population. This finding may indicate that women with cesarean delivery are at higher risk of having a hysterectomy later in life. Due to the study design, our study does not allow conclusions as to the cause of this observation; however, we suggest that cesarean delivery and hysterectomy may have promoters in common (eg, poorer gynecological health) or that factors caused by cesarean delivery per se are involved (eg, chronic pain, bleeding disorders, adenomyosis, and adhesions).

The risk for all complications was only slightly greater for women having 2 or more cesarean deliveries compared with women having only 1 cesarean delivery. This small relative influence may be explained by the fact that the women with 2 or more cesarean deliveries were younger than the women with only 1 previous cesarean delivery.

We also found that having a previous cesarean delivery increased a woman’s risk of undergoing open surgery for a benign hysterectomy. Earlier investigations have shown that minimally invasive surgery benefits the patient compared with open surgery with regard to shorter recovery time, less pain, and smaller incisions. Whether vaginal hysterectomy is an appropriate route of surgery for women with previous cesarean deliveries is a topic of debate due to concerns about the increased risk of bladder injuries and decreased uterine mobility in the setting of anterior wall adhesions. Vaginal hysterectomy may also be more challenging because of decreased mobility of the uterus from the adhesions after cesarean deliveries.

This study adds to the existing knowledge on long-term influences of cesarean delivery. Our results imply that information on long-term associations should be made more readily available to women, clinicians, and policymakers and suggest that decisions on cesarean delivery should take into account not only immediate maternal and neonatal influences but also women’s health in the long term, including an increased risk of reoperation and complications associated with surgery later in life.

Conclusions

Having a previous cesarean delivery significantly increased the risk of reoperation, perioperative and postoperative complications, and blood transfusion among women undergoing a hysterectomy later in life. Furthermore, cesarean delivery increased a woman’s risk of open surgery for a subsequent hysterectomy. The results support policies and clinical efforts to prevent cesarean deliveries that are not medically indicated.

eTable 1. Summary of Diagnosis and Surgical Codes

eTable 2. Adjusted Odds Ratio for Reoperation, Complications, and Blood Transfusion Stratified by Route of Hysterectomy

Reference

- 1.Betrán AP, Ye J, Moller AB, Zhang J, Gülmezoglu AM, Torloni MR. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: global, regional and national estimates: 1990-2014. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macfarlane AJ, Blondel B, Mohangoo AD, et al. ; Euro-Peristat Scientific Committee . Wide differences in mode of delivery within Europe: risk-stratified analyses of aggregated routine data from the Euro-Peristat study. BJOG. 2016;123(4):559-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibbons L, Belizán JM, Lauer JA, Betrán AP, Merialdi M, Althabe F. The Global Numbers and Costs of Additionally Needed and Unnecessary Caesarean Sections Performed per Year: Overuse as a Barrier to Universal Coverage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; World Health Report 2010. Background Paper 30.

- 4.Molina G, Weiser TG, Lipsitz SR, et al. . Relationship between cesarean delivery rate and maternal and neonatal mortality. JAMA. 2015;314(21):2263-2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall NE, Fu R, Guise JM. Impact of multiple cesarean deliveries on maternal morbidity: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(3):262.e1-262.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Villar J, Carroli G, Zavaleta N, et al. ; World Health Organization 2005 Global Survey on Maternal and Perinatal Health Research Group . Maternal and neonatal individual risks and benefits associated with caesarean delivery: multicentre prospective study. BMJ. 2007;335(7628):1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clark SL, Belfort MA, Dildy GA, Herbst MA, Meyers JA, Hankins GD. Maternal death in the 21st century: causes, prevention, and relationship to cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(1):36.e1-36.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solheim KN, Esakoff TF, Little SE, Cheng YW, Sparks TN, Caughey AB. The effect of cesarean delivery rates on the future incidence of placenta previa, placenta accreta, and maternal mortality. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;24(11):1341-1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nikolajsen L, Sørensen HC, Jensen TS, Kehlet H. Chronic pain following caesarean section. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2004;48(1):111-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lyell DJ. Adhesions and perioperative complications of repeat cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;205(6)(suppl):S11-S18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dansk Hysterektomi og Hysteroskopi Database. 2015/2016 Annual report. http://www.dsog.dk/koder-og-kvalitetssikring/dansk-hysterektomi-og-hysteroskopi-database/. Accessed April 15, 2016.

- 12.Duong TH, Patterson TM. Lower urinary tract injuries during hysterectomy in women with a history of two or more cesarean deliveries: a secondary analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25(8):1037-1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee MS, Venkatesh KK, Growdon WB, Ecker JL, York-Best CM. Predictors of 30-day readmission following hysterectomy for benign and malignant indications at a tertiary care academic medical center. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(5):607.e1-607.e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):22-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):30-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):38-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baadsgaard M, Quitzau J. Danish registers on personal income and transfer payments. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):103-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Datatilsynet: compiled version of the Act on Processing of Personal Data. https://www.datatilsynet.dk/english/the-act-on-processing-of-personal-data/read-the-act-on-processing-of-personal-data/compiled-version-of-the-act-on-processing-of-personal-data/. Accessed April 1, 2016.

- 19.Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I, Brønnum-Hansen H. Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(7)(suppl):12-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. What are equivalence scales? http://www.oecd.org/eco/growth/OECD-Note-EquivalenceScales.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- 21.R Core Team R: a language and environment for statistical computing. http://www.gbif.org/resource/81287. Accessed April 1, 2016.

- 22.Osler M, Daugbjerg S, Frederiksen BL, Ottesen B. Body mass and risk of complications after hysterectomy on benign indications. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(6):1512-1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rahmouni K, Correia ML, Haynes WG, Mark AL. Obesity-associated hypertension: new insights into mechanisms. Hypertension. 2005;45(1):9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hruby A, Manson JE, Qi L, et al. . Determinants and consequences of obesity. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(9):1656-1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Settnes A. Annual report 2011. Danish Hysterectomy and Hysteroscopic Database; 2011. http://gynobsguideline.dk/files/DHHDrapport2011.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2016.

- 26.Levin D, Tulandi T. Dense adhesions between the uterus and anterior abdominal wall: a unique complication of cesarean delivery. Gynecol Surg. 2011;8:415-416. doi: 10.1007/s10397-010-0633-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rattray JE, Johnston M, Wildsmith JA. Predictors of emotional outcomes of intensive care. Anaesthesia. 2005;60(11):1085-1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aarts JW, Nieboer TE, Johnson N, et al. . Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(8):CD003677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rooney CM, Crawford AT, Vassallo BJ, Kleeman SD, Karram MM. Is previous cesarean section a risk for incidental cystotomy at the time of hysterectomy? a case-controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(6):2041-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bogani G, Cromi A, Serati M, et al. . Hysterectomy in patients with previous cesarean section: comparison between laparoscopic and vaginal approaches. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;184:53-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sheth SS. Vaginal hysterectomy in women with a history of 2 or more cesarean deliveries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122(1):70-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Summary of Diagnosis and Surgical Codes

eTable 2. Adjusted Odds Ratio for Reoperation, Complications, and Blood Transfusion Stratified by Route of Hysterectomy