Key Points

Question

Are adverse postoperative events higher among patients with ulcerative colitis who require anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy?

Findings

In this analysis involving the insurance claims records of 2476 patients who underwent colectomy or total proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis, preoperative anti-TNF agent use was not associated with a significant increase in postoperative complications. However, anti-TNF agent use within 90 days of surgery among patients who underwent ileal pouch-anal anastomosis was associated with higher complication rates.

Meaning

For patients using anti-TNF therapy for ulcerative colitis, avoidance of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis during the initial ulcerative colitis–associated procedure may be warranted.

Abstract

Importance

Despite the increasing use of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy in ulcerative colitis, its effects on postoperative outcomes remain unclear, with many patients requiring surgical intervention despite optimal medical management.

Objective

To assess the association of preoperative use of anti-TNF agents with adverse postoperative outcomes.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This analysis used insurance claims data from a large national database to identify patients 18 years or older with ulcerative colitis. These insured patients had inpatient and/or outpatient claims between January 1, 2005, and December 31, 2013, with Current Procedural Terminology codes for a subtotal colectomy or total abdominal colectomy, a total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy, or a combined total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Only data regarding the first or index surgical admission within the time frame were abstracted. Use of anti-TNF agents, corticosteroids, and immunomodulators within 90 days of surgery was identified using Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes. Inclusion in the study required the patient to have an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code for ulcerative colitis. Exclusion occurred if the patient had a secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for Crohn disease or if the patient was not continuously enrolled in an insurance plan for at least 180 days before and after the index surgery. Data were collected and analyzed from February 1, 2015, to June 2, 2016.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Outcomes included 90-day complications, emergency department visits, and readmissions. Multivariable logistic regression was used to model covariates, including anti-TNF agent use, on the occurrence of outcomes.

Results

Of the 2476 patients identified, 1379 (55.7%) were men, and the mean (SD) age was 42.1 (12.9) years. Among these, 950 (38.4%) underwent subtotal colectomy or total abdominal colectomy, 354 (14.3%) underwent total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy, and 1172 (47.3%) received ileal pouch-anal anastomoses. In univariate analyses, increased postoperative complications were observed among patients in the ileal pouch cohort who received anti-TNF agents preoperatively vs those who did not (137 [45.2%] vs 327 [37.6%]; P = .02) but not among those in the colectomy or proctocolectomy cohorts. An increase in complications was also observed on multivariable analyses among patients in the ileal pouch cohort (odds ratio, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.05-1.82).

Conclusions and Relevance

Unlike preoperative anti-TNF agent use among patients who underwent colectomy or total proctocolectomy and experienced no significant increase in postoperative complications, anti-TNF agent use within 90 days of surgery among patients who underwent ileal pouch-anal anastomosis was associated with higher 90-day postoperative complication rates.

This study examines inpatient and outpatient claims data from a large national database to determine the association of preoperative anti-TNF therapy with postoperative complications among surgical patients with ulcerative colitis.

Introduction

Medical therapies for inflammatory bowel diseases continue to evolve, but surgical interventions maintain a significant role, particularly in ulcerative colitis (UC). The clinical course of UC exhibits a highly variable spectrum of severity among patients. Approximately 50% of patients with chronic disease will relapse each year, and up to 90% of these patients will experience at least 1 relapse in 25 years. Even with optimal medical management, approximately one-third of patients with UC requiring hospitalization for their disease will ultimately undergo surgery. Most of these patients experience either insufficient responses to medical therapy or intolerable adverse effects from medications.

The first class of biologic agents used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel diseases comprised antibodies targeting tumor necrosis factor (TNF), a pro-inflammatory cytokine. Infliximab first gained US Food and Drug Administration approval for the treatment of UC in 2005 and was followed several years later by adalimumab. By interfering with the inflammatory cascade, anti-TNF agents have demonstrated improved mucosal healing, reductions in corticosteroid requirements, and induction or maintenance of remission. However, because these underlying inflammatory mechanisms are also implicated in wound healing and infection defense, impairing these mechanisms in a surgical patient is justly met with some caution.

Initially, approval of infliximab for UC was limited to patients with moderate to severe disease. Although described more thoroughly within the Crohn disease literature, a “top-down” approach, which employs early use of biologic agents to induce remission and is followed by maintenance with immunomodulators, has received increased emphasis. This approach has also been used in patients with UC, and it has been suggested that a subgroup of patients with UC may benefit from this strategy. Furthermore, the indications for anti-TNF therapy have expanded to include salvage therapy for corticosteroid-resistant cases, decreasing the emergency colectomy rate to 29%. Although improved, the colectomy population still represents a substantial proportion of patients undergoing surgery after a recent anti-TNF administration. The once-distinct indications for surgical and medical therapy are increasingly converging, and the patients who are now candidates for anti-TNF agents are the same ones who remain at high risk for surgery. Understanding the potential effect of administering anti-TNF agents on the surgical patient is therefore critical. In this study, we used a large national claims database to explore the effects of anti-TNF agents on surgical patients with UC.

Methods

Data

Between February 1, 2015, and June 2, 2016, we used the MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (CCAE) database (Truven Health Analytics) to identify the patient cohort for this study. The CCAE database captures both inpatient and outpatient claims, including outpatient pharmaceutical claims, for patients (as well as their spouses and dependents) with employer-based private insurance in the United States. Because it is based on insurance enrollment, the database contains information that has a strong longitudinal integrity throughout inpatient and outpatient encounters. The inclusion of both inpatient and outpatient pharmaceutical data, including prescription fills, provides an accurate reflection of patient medication utilization patterns and is a large advantage of this database. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, Pennsylvania. The need for patient informed consent was waived for this study by the institutional review board of the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center because of the minimal risk of this study.

Patient Selection

A total of 2476 patients 18 years or older were identified through the CCAE database. These patients had inpatient and/or outpatient claims from January 1, 2005, through December 31, 2013, with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes indicating a subtotal colectomy without primary anastomosis or total abdominal colectomy (STC/TAC) (CPT codes 44141, 44143, 44144, 44146, 44147, 44150, 44151, 44206, 44208, and 44210), a total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy (TPC/EI; CPT codes 44155, 44156, and 44212), or a combined total proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis (IPAA; CPT codes 44152, 44153, 44157, 44158, and 44211). Patients who underwent an IPAA with CPT code 44152 or 44153 or a stoma reversal (CPT codes 44227, 44620, 44625, and 44626) within 6 months after their index procedure were designated as receiving a diverting loop ileostomy. International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes for UC (556.0-556.6, 556.8, and 556.9) were used to isolate patients with a UC diagnosis for inclusion in this study. If multiple admissions involving a surgical procedure were identified, then only data regarding the first surgical admission within the time frame were abstracted to identify the index UC-related procedure for each patient. Patients were excluded if they had a secondary ICD-9-CM diagnosis code for Crohn disease or if they were not continuously enrolled in an insurance plan for at least 180 days before and after the index surgery.

Covariates

Preoperative comorbidities were identified with claims within 180 days prior to surgery using the Quan modification of the Charlson Comorbidity Index, which is based on 17 comorbidities. Additional comorbidities were identified using ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for various types of protein-calorie malnutrition (260.X, 261.X, 262.X, and 263.X) and for failure to thrive (783.2 and 783.7). Use of anti-TNF agents, corticosteroids, and immunomodulators within 90 days of surgery was identified using Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes for inpatient and outpatient claims and using generic names for outpatient pharmaceutical claims. Anti-TNF agents were adalimumab (J0135), certolizumab pegol (J0717), and infliximab (J1745). Corticosteroids were prednisone (J7506); hydrocortisone acetate, hydrocortisone sodium phosphate, and hydrocortisone sodium succinate (J1700, J1710, and J1720); and methylprednisolone, methylprednisolone acetate, and methylprednisolone sodium succinate (J1020, J1030, J1040, J2920, J2930, and J7509). Immunomodulators were azathioprine sodium (J7500, J7501), 6-mercaptopurine (S0108), and cyclosporine (J7502, J7515, and J7516). For patients with anti-TNF agent use, the most recent day prior to surgery when there was a claim for a biologic agent was collected. Emergency cases were defined as those with a claim for an emergency department (ED) visit within 2 days of the surgical procedure.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes of interest within each surgical group included complications, postoperative ED visits, and readmissions. Complications were defined according to the description by Loftus and colleagues of postoperative complications relevant to patients with UC undergoing colorectal resections. These complications were identified from inpatient and outpatient claims with CPT or ICD-9-CM codes within 90 days of discharge; they included fistula, abscess, stricture, sepsis-pneumonia-bacteremia, wound debridement or dehiscence, anal/rectal repair or manipulation, lysis of adhesions, and revision of ileostomy. Postoperative ED visits were defined as a service subcategory code of 20 for inpatient and outpatient claims. Readmissions were defined as any inpatient claim within 90 days of discharge. Among patients receiving biologic agents, we examined whether receiving an infusion closer to the date of the index surgery affected postsurgical outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

Wilcoxon and χ2 tests, as appropriate, were used to compare preoperative variables and postoperative outcomes between patients receiving and patients not receiving anti-TNF agents in each surgical group. Multivariable logistic regression was used to model the occurrence of each outcome within 90 days by the following covariates: anti-TNF agent use, age, sex, comorbidity index, malnutrition, failure to thrive, corticosteroid use, immunomodulator use, emergency case, and presence of diverting stoma (among the IPAA cohort only). A linear association for comorbidity index was assumed. Nonlinear associations (on the log-odds scale) for age were examined in these models using B-splines, but linear associations were found to be appropriate in all cases and were used in the final models. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% CIs were reported for all factors in the models. P < .05 was considered statistically significant, and 2-sided P values were used.

Among the subset of patients who received anti-TNF therapy, we examined whether outcomes differed according to time between anti-TNF agent use and surgery. Univariable logistic regression was used to model the occurrence of each outcome as a function of time since infusion. Nonlinear curves for day were tested using B-splines, but all nonlinear curves were nonsignificant, and thus linear curves were fit. The estimated probabilities of each outcome as a function of time were reported for these models. Multivariable analyses could not be performed because the event rates of each outcome were too small.

In addition, sensitivity analysis that excluded patients undergoing emergency surgery was performed given the inherent heterogeneity in disease severity and operative complexity in this population. All logistic models were refit after these exclusions.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and R software, version 3.1.2 (http://www.r-project.org).

Results

Of the 2476 patients identified, 1379 (55.7%) were men and 1097 (44.3%) were women. The mean (SD) age of all patients was 42.1 (12.9) years.

Subtotal Colectomy or Total Abdominal Colectomy

A total of 950 patients (38.4%) who underwent an STC/TAC procedure were identified (Table 1), of whom 254 (26.7%) had claims for an anti-TNF agent—primarily infliximab (Table 2)—within 90 days of surgery, given at a mean (SD) of 39.1 (22.3) days prior to surgery. Patients receiving anti-TNF agents compared with those with no anti-TNF agent use were significantly younger (mean [SD] age, 37.6 [13.42] years vs 42.4 [13.36] years; P < .001) and underwent fewer emergency surgical procedures (33 [13%] vs 191 [27.4%]; P < .001) but did not differ regarding sex, comorbidity index, or malnutrition status (Table 1). Significantly more patients receiving anti-TNF therapy compared with those with no anti-TNF agent use had corticosteroid use (170 [66.9%] vs 361 [51.9%]; P < .001) and immunomodulator use (69 [27.2%] vs 145 [20.8%]; P = .04).

Table 1. Patient Demographics Among 3 Surgical Cohorts.

| Characteristic | STC/TAC, No. (%) (n = 950) |

TPC/EI, No. (%) (n = 354) |

IPAA, No. (%) (n = 1172) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Anti-TNF Agent Use (n = 696) |

Anti-TNF Agent Use (n = 254) |

P Value | No Anti-TNF Agent Use (n = 261) |

Anti-TNF Agent Use (n = 93) |

P Value | No Anti-TNF Agent Use (n = 869) |

Anti-TNF Agent Use (n = 303) |

P Value | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 42.4 (13.36) | 37.6 (13.42) | <.001 | 50.5 (10.81) | 47.4 (11.65) | .01 | 41.2 (12.00) | 38.6 (12.66) | .002 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 368 (52.9) | 151 (59.4) | .07 | 139 (53.3) | 57 (61.3) | .18 | 498 (57.3) | 166 (54.8) | .45 |

| Female | 328 (47.1) | 103 (40.6) | 122 (46.7) | 36 (38.7) | 371 (42.7) | 137 (45.2) | |||

| Comorbidity index (CCI) | |||||||||

| 0 | 531 (76.3) | 196 (77.2) | .58 | 181 (69.3) | 72 (77.4) | .29 | 704 (81) | 261 (86.1) | .07 |

| 1 | 60 (8.6) | 27 (10.6) | 30 (11.5) | 11 (11.8) | 56 (6.4) | 21 (6.9) | |||

| 2 | 72 (10.3) | 22 (8.7) | 35 (13.4) | 8 (8.6) | 84 (9.7) | 16 (5.3) | |||

| ≥3 | 33 (4.7) | 9 (3.5) | 15 (5.7) | 2 (2.2) | 25 (2.9) | 5 (1.7) | |||

| Malnutrition | 49 (7) | 26 (10.2) | .11 | 14 (5.4) | 10 (10.8) | .08 | 18 (2.1) | 13 (4.3) | .04 |

| Failure to thrive | 37 (5.3) | 27 (10.6) | .004 | 20 (7.7) | 9 (9.7) | .54 | 24 (2.8) | 13 (4.3) | .19 |

| Emergent procedure | 191 (27.4) | 33 (13) | <.001 | 24 (9.2) | 14 (15.1) | .12 | 35 (4) | 16 (5.3) | .36 |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; STC/TAC, subtotal colectomy or total abdominal colectomy; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TPC/EI, total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy.

Table 2. Medication Use Within 90 Days of Surgery Among 3 Cohorts.

| Medication | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| STC/TAC (n = 950) |

TPC/EI (n = 354) |

IPAA (n = 1172) |

|

| Corticosteroids | 531 (55.9) | 182 (51.4) | 557 (47.5) |

| Immunomodulator | 214 (22.5) | 79 (22.3) | 298 (25.4) |

| Azathioprine sodium | 138 (14.5) | 47 (13.3) | 175 (14.9) |

| 6-Mercaptopurine | 76 (8) | 31 (8.8) | 125 (10.7) |

| Cyclosporine | 3 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) |

| Anti-TNF agent | 254 (26.7) | 93 (26.3) | 303 (25.9) |

| Infliximab | 198 (20.8) | 68 (19.2) | 237 (20.2) |

| Adalimumab | 53 (5.6) | 25 (7.1) | 63 (5.4) |

| Certolizumab pegol | 8 (0.8) | 4 (1.1) | 3 (0.3) |

Abbreviations: IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; STC/TAC, subtotal colectomy or total abdominal colectomy; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TPC/EI, total proctocolectomy with end ileostomy.

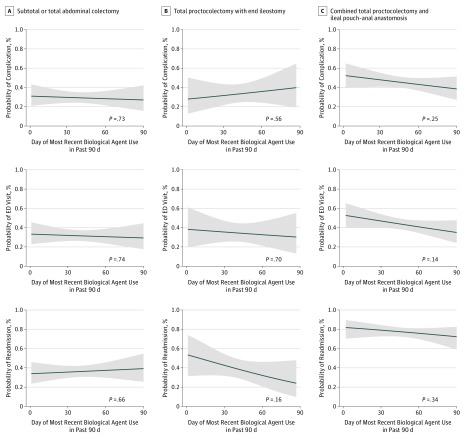

In univariate analyses, patients receiving anti-TNF agents compared with those with no anti-TNF agent use had fewer ED visits within 90 days of surgery (79 [31.1%] vs 270 [38.8%]; P = .03), but there were no differences in readmissions or complications. On multivariable analyses, however, the receipt of therapy was not significantly associated with these outcomes (Table 3). Among patients who received a biologic agent, the timing of its most recent administration did not influence the occurrence of any adverse outcomes within 90 days (Figure, A).

Table 3. Logistic Regression Analyses for 90-Day Postoperative Outcome Variables.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Complication | P Value | Emergency Department Visit | P Value | Readmission | P Value | |

| Subtotal Colectomy or Total Abdominal Colectomy | ||||||

| Anti-TNF agent use | 0.86 (0.62-1.18) | .35 | 0.73 (0.53-1.00) | .052 | 0.82 (0.60-1.11) | .20 |

| Age, 10-y increase | 0.96 (0.87-1.06) | .40 | 0.89 (0.81-0.98) | .02 | 0.80 (0.72-0.88) | <.001 |

| Female | 1.31 (1.01-1.71) | .045 | 1.18 (0.91-1.52) | .22 | 1.02 (0.79-1.32) | .87 |

| CCI, 1-point increase | 0.99 (0.87-1.11) | .83 | 1.11 (0.99-1.25) | .07 | 1.17 (1.04-1.31) | .007 |

| Malnutrition | 1.12 (0.68-1.83) | .65 | 1.03 (0.63-1.67) | .91 | 0.96 (0.58-1.56) | .87 |

| Failure to thrive | 1.14 (0.66-1.92) | .64 | 1.05 (0.62-1.76) | .85 | 1.37 (0.82-2.28) | .23 |

| Corticosteroid use | 0.94 (0.72-1.25) | .69 | 1.26 (0.96-1.66) | .09 | 1.28 (0.98-1.68) | .07 |

| Immunomodulator use | 1.14 (0.82-1.58) | .43 | 1.13 (0.82-1.55) | .47 | 1.22 (0.89-1.68) | .22 |

| Emergency procedure | 1.19 (0.87-1.62) | .27 | 1.34 (0.99-1.80) | .06 | 1.22 (0.90-1.65) | .20 |

| Total Proctocolectomy With End Ileostomy | ||||||

| Anti-TNF agent use | 1.01 (0.59-1.70) | .98 | 0.95 (0.55-1.59) | .83 | 1.83 (1.08-3.10) | .02 |

| Age, 10-y increase | 1.06 (0.87-1.31) | .56 | 0.84 (0.69-1.03) | .10 | 0.94 (0.76-1.16) | .54 |

| Female | 1.17 (0.75-1.84) | .49 | 0.66 (0.41-1.04) | .07 | 1.22 (0.75-1.96) | .42 |

| CCI, 1-point increase | 1.05 (0.84-1.31) | .67 | 1.11 (0.89-1.39) | .36 | 0.95 (0.73-1.21) | .67 |

| Malnutrition | 0.95 (0.34-2.42) | .91 | 1.05 (0.39-2.67) | .92 | 1.65 (0.63-4.19) | .29 |

| Failure to thrive | 0.60 (0.22-1.43) | .27 | 0.41 (0.14-1.02) | .07 | 0.55 (0.19-1.37) | .23 |

| Corticosteroid use | 0.67 (0.42-1.05) | .08 | 0.88 (0.56-1.40) | .60 | 1.08 (0.66-1.75) | .76 |

| Immunomodulator use | 1.13 (0.65-1.93) | .66 | 1.07 (0.62-1.83) | .80 | 0.96 (0.54-1.68) | .89 |

| Emergency procedure | 0.92 (0.43-1.90) | .83 | 1.31 (0.63-2.66) | .46 | 0.78 (0.34-1.67) | .54 |

| Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis | ||||||

| Anti-TNF agent use | 1.38 (1.05-1.82) | .02 | 0.85 (0.65-1.11) | .24 | 0.96 (0.70-1.35) | .83 |

| Age, 10-y increase | 1.07 (0.96-1.18) | .21 | 0.96 (0.87-1.06) | .38 | 0.99 (0.88-1.11) | .82 |

| Female | 1.30 (1.02-1.65) | .03 | 1.35 (1.07-1.71) | .01 | 1.37 (1.03-1.84) | .03 |

| CCI, 1-point increase | 1.05 (0.91-1.21) | .50 | 1.04 (0.91-1.20) | .55 | 1.00 (0.85-1.19) | .97 |

| Malnutrition | 1.25 (0.59-2.61) | .56 | 0.75 (0.35-1.57) | .45 | 0.73 (0.31-1.93) | .50 |

| Failure to thrive | 0.68 (0.32-1.36) | .29 | 1.03 (0.52-2.03) | .92 | 2.26 (0.91-6.87) | .11 |

| Corticosteroid use | 1.03 (0.81-1.32) | .80 | 1.26 (0.99-1.61) | .06 | 1.25 (0.93-1.68) | .14 |

| Immunomodulator use | 1.02 (0.77-1.34) | .90 | 1.11 (0.84-1.46) | .45 | 0.92 (0.66-1.28) | .61 |

| Emergency procedure | 1.47 (0.83-2.62) | .18 | 2.68 (1.48-5.07) | .002 | 1.05 (0.54-2.16) | .88 |

| Diverting stoma | 0.89 (0.66-1.22) | .47 | 1.10 (0.81-1.50) | .55 | 4.18 (3.02-5.78) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; OR, odds ratio; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Figure. Logistic Regression Models of Complications, Emergency Department (ED) Visits, and Readmissions Within 90 Days.

Each outcome is shown on a separate row for each surgical group. Black lines indicate probabilities; gray regions, 95% CIs.

Total Proctocolectomy With End Ileostomy

For TPC/EI procedures, a total of 354 patients (14.3%) were identified (Table 1). Approximately 93 patients (26.3%) received an anti-TNF agent within 90 days of surgery (Table 2). Again, infliximab was the most commonly used agent, given at a mean (SD) of 41.5 (20.9) days before surgery. Patients receiving anti-TNF agents compared with those with no anti-TNF agent use were younger (mean [SD] age, 47.4 [11.65] years vs 50.5 [10.81] years; P = .01) and more likely to be receiving corticosteroids (62 [66.7%] vs 120 [46.0%]; P = .001) or immunomodulators (30 [32.3%] vs 49 [18.8%]; P = .007), but they did not significantly differ in sex, comorbidity index, or emergency surgical procedure (Table 1).

Compared with those with no anti-TNF agent use, patients receiving anti-TNF therapy did not have more complications or ED visits but did have higher readmission rates within 90 days (66 [25.3%] vs 36 [38.7%]; P = .01). This association was also observed on multivariable analyses (Table 3). No associations were found between the timing of preoperative anti-TNF administration prior to the index surgery and occurrence of adverse postoperative outcomes within 90 days (Figure, B).

Ileal Pouch-Anal Anastomosis

A total of 1172 patients (47.3%) who underwent IPAA as their index UC-related procedure were identified (Table 1). As in the other 2 cohorts, 303 patients (25.9%) in the IPAA cohort received anti-TNF agents, most of which was infliximab (Table 2) given at a mean (SD) of 46.6 (21.1) days before surgery. Patients receiving anti-TNF agents compared with those with no anti-TNF agent use were younger (mean [SD] age, 38.6 [12.66] years vs 41.2 [12] years; P = .002) and had a higher proportion of malnutrition (13 [4.3%] vs 18 [2.1%]; P = .04), corticosteroid use (191 [63.0%] vs 366 [42.1%]; P < .001), and immunomodulator use (96 [31.7%] vs 202 [23.2%]; P = .004) but similar proportions of emergency surgical procedures (Table 1).

Among patients in the IPAA cohort, no significant associations were noted between anti-TNF therapy and either ED visits or 90-day readmissions on either univariate analyses or multivariable analyses. However, unlike the STC/TAC and TPC/EI cohorts, the IPAA cohort had a significantly higher incidence of complications within 90 days of surgery (137 [45.2%] vs 327 [37.6%]; P = .02). This result was also observed on multivariable logistic regression; use of a biologic agent was associated with 38% higher odds of complications (OR, 1.38; 95% CI, 1.05-1.82). Because of this significant association, further analysis was performed to identify the specific complications responsible for this association (Table 4). Timing of anti-TNF therapy up to 90 days prior to the index surgery did not appear to influence the complication rate (Figure, C).

Table 4. Reported 90-Day Postoperative Complications in the IPAA Cohort.

| Complication | No. (%) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Anti-TNF Agent Use (n = 869) |

Anti-TNF Agent Use (n = 303) |

||

| Fistula | 96 (11) | 42 (13.9) | .19 |

| Abscess | 154 (17.7) | 56 (18.5) | .77 |

| Stricture | 18 (2.1) | 9 (3) | .37 |

| Sepsis-pneumonia-bacteremia | 86 (9.9) | 40 (13.2) | .11 |

| Wound debridement and dehiscence | 39 (4.5) | 22 (7.3) | .06 |

| Anal/rectal repair or manipulation | 43 (4.9) | 20 (6.6) | .27 |

| Lysis of adhesions | 15 (1.7) | 14 (4.6) | .005 |

| Revision of ileostomy | 10 (1.2) | 4 (1.3) | .82 |

Abbreviations: IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

Sensitivity Analysis

To test the robustness of these findings, a sensitivity analysis was performed that excluded all emergency cases in all logistic models. The estimated ORs from these models were similar to the estimates when using all patients for the 3 surgical groups and the 3 adverse postoperative outcomes.

Discussion

In the current literature, significant heterogeneity has been reported regarding the effects of anti-TNF agents on surgical patients with UC. Existing data are primarily based on retrospective studies, which vary by the types of surgery included (resections vs IPAA-related procedures) and the biologic agents studied (infliximab alone vs with adalimumab and certolizumab) and are often limited by small sample sizes. Most have shown no difference in outcomes, but several have suggested either increased infectious or total postoperative complications among patients who received anti-TNF agents preoperatively. Multiple meta-analyses have also yielded contradictory results, and the literature is similarly conflicted regarding postoperative complications associated with anti-TNF agent use in Crohn disease.

In this study, only patients in the IPAA cohort demonstrated an increase in 90-day complications after preoperative use of anti-TNF agents. A sensitivity analysis removing any patients who had an ED visit within 2 days of admission corroborated this finding. This finding has been observed in several other studies, all of which included only patients undergoing IPAA-related procedures. Of the 3 studies that also exclusively examined patients who underwent IPAA procedures but did not identify increases in complications, the anti-TNF arms had relatively small sample sizes of fewer than 30 patients and may not have been powered adequately to detect differences in complication rates.

In this study, as opposed to having an effect on restorative procedures, anti-TNF agents had no detrimental effect on postoperative complications in patients who underwent resection (STC/TAC or TPC/EI) as their initial UC-related surgery. Previous studies that examined patients undergoing only resection are sparse, with only a few studies examining patients undergoing only colectomy. Rather, many studies include mixed cohorts of patients undergoing both resection only and resection with IPAA. Of these studies, none identified an increased risk of postoperative complications in patients on preoperative anti-TNF therapy. A retrospective study by Gu and colleagues, which stratified patients into those undergoing total proctocolectomy with IPAA vs subtotal colectomy, found increased rates of pelvic sepsis among patients who underwent IPAA and were receiving biologic therapy but no increased complications among patients who underwent colectomy and were receiving biologic therapy, which are consistent with our current findings. Considering mixed groups of surgical patients may, therefore, be diluting a detrimental effect of biologic agents on patients who underwent IPAA and was an observation suggested in a meta-analysis by Selvaggi and colleagues.

Given the complexity of IPAA procedures, it is not surprising that this cohort appears more vulnerable to alterations in the inflammatory cascade induced by anti-TNF agents. The complications that either met or approached statistical significance between the groups included those associated with wound debridement or dehiscence or adhesion formation. This profile of complications suggests that these alterations in the inflammatory process may affect wound healing, although further studies focusing on this association are warranted.

Although data on infliximab use in surgical patients with UC are conflicted, data on other anti-TNF agents in this population are largely absent. Of those that do include adalimumab and certolizumab, a variable effect of anti-TNF agents on postoperative complications was noted, similar to studies examining infliximab alone. One study performed a subgroup analysis directly comparing complications between infliximab and adalimumab users and found no differences between the agents. As the oldest biologic agent, infliximab offers the largest clinical experience and body of supporting literature but requires in-office intravenous infusion, unlike the subcutaneous self-administration permitted by adalimumab and certolizumab. Furthermore, because various clinical considerations and emerging resistance patterns are used to guide the choice of biologic agents, an improved understanding of any differences between these 3 agents in a surgical population is an important area for future research.

Several other significant associations identified in this study are consistent with previous findings in the literature. Female sex was associated with increased odds of all 3 adverse outcomes among patients in the IPAA group and with increased postoperative complications among patients in the STC/TAC group. A large retrospective study by Riegler and colleagues noted an association of female sex and increased disease activity with greater colitis extent. Conversely, increasing age was associated with reduced disease severity in that study; in our study, older patients in the STC/TAC cohort were found to have decreased odds of ED visits and readmissions. Interestingly, corticosteroid use was not found to be associated with postoperative complications after controlling for other patient covariates. The use of certain medications (eg, corticosteroids and immunomodulators) in this study was considered binary because dosages could not always be identified within the CCAE database. This limitation may have biased our results either toward the null hypothesis (by overestimating the effect of corticosteroids in patients who received only 1 dose) or toward showing a significant difference if the corticosteroid dosages used among anti-TNF patients were substantially higher than among patients not receiving anti-TNF therapy.

Limitations

Several limitations are present in this study. First, using the CCAE database, we were unable to determine whether patients had received inpatient infusions of anti-TNF agents preoperatively, thus potentially misclassifying some of the patients receiving anti-TNF agents and biasing the results toward the null hypothesis. Second, the CCAE database contains only privately insured patients and thus does not include the Medicare population (all patients 65 years or older), the Medicaid population, or individuals without health insurance. Although this proportion still represents most patients with UC, this subset is still not generalizable to the entire UC population because a previous study estimated that only 58% of patients with UC have continuous enrollment in a private health insurance plan for at least 1 year. Third, although anastomotic leaks lack a specific ICD-9-CM code, they are commonly associated with intra-abdominal abscesses, which are captured by the definition of complications by Loftus and colleagues. Finally, because only the initial procedure that patients underwent was captured in this analysis, we were unable to compare patients undergoing delayed completion proctectomy with IPAA with patients undergoing TPC with primary IPAA.

Conclusions

Postoperative complications were not increased among patients with UC receiving preoperative anti-TNF agents who underwent resection alone (STC/TAC or TPC/EI). Among patients undergoing a restorative procedure as their index UC-related procedure, however, the use of anti-TNF therapy within 90 days of surgery was associated with increased complications. Therefore, in a patient who is a candidate for a restorative procedure, our data suggest that performing a TPC with concurrent IPAA as the initial UC-related procedure should be avoided or at least delayed for more than 90 days after anti-TNF agent use. It remains unclear whether a 3-stage or a modified 2-stage approach (initial subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy followed by completion proctectomy with IPAA and no proximal diversion) is a safer alternative. A previous study suggested that patients receiving biologic agents who undergo delayed IPAA do not experience the complications observed in patients undergoing primary IPAA; however, further studies using larger cohorts are warranted to directly compare these 2 cohorts of patients.

References

- 1.Langholz E, Munkholm P, Davidsen M, Binder V. Course of ulcerative colitis: analysis of changes in disease activity over years. Gastroenterology. 1994;107(1):3-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Selvasekar CR, Cima RR, Larson DW, et al. . Effect of infliximab on short-term complications in patients undergoing operation for chronic ulcerative colitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(5):956-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biondi A, Zoccali M, Costa S, Troci A, Contessini-Avesani E, Fichera A. Surgical treatment of ulcerative colitis in the biologic therapy era. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(16):1861-1870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gainsbury ML, Chu DI, Howard LA, et al. . Preoperative infliximab is not associated with an increased risk of short-term postoperative complications after restorative proctocolectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(3):397-403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devaraj B, Kaiser AM. Surgical management of ulcerative colitis in the era of biologicals. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(1):208-220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Devlin SM, Panaccione R. Evolving inflammatory bowel disease treatment paradigms: top-down versus step-up. Med Clin North Am. 2010;94(1):1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sandborn WJ. Step-up versus top-down therapy in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2007;3(1):16-17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Järnerot G, Hertervig E, Friis-Liby I, et al. . Infliximab as rescue therapy in severe to moderately severe ulcerative colitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(7):1805-1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quint J. Health Research Data for the Real World: The MarketScan Databases. Ann Arbor, MI: Truven Health Analytics Inc; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, et al. . Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Loftus EV Jr, Delgado DJ, Friedman HS, Sandborn WJ. Colectomy and the incidence of postsurgical complications among ulcerative colitis patients with private health insurance in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(7):1737-1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ferrante M, D’Hoore A, Vermeire S, et al. . Corticosteroids but not infliximab increase short-term postoperative infectious complications in patients with ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(7):1062-1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krane MK, Allaix ME, Zoccali M, et al. . Preoperative infliximab therapy does not increase morbidity and mortality after laparoscopic resection for inflammatory bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(4):449-457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau C, Dubinsky M, Melmed G, et al. . The impact of preoperative serum anti-TNFα therapy levels on early postoperative outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;261(3):487-496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nørgård BM, Nielsen J, Qvist N, Gradel KO, de Muckadell OB, Kjeldsen J. Pre-operative use of anti-TNF-α agents and the risk of post-operative complications in patients with ulcerative colitis—a nationwide cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35(11):1301-1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schluender SJ, Ippoliti A, Dubinsky M, et al. . Does infliximab influence surgical morbidity of ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in patients with ulcerative colitis? Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50(11):1747-1753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waterman M, Xu W, Dinani A, et al. . Preoperative biological therapy and short-term outcomes of abdominal surgery in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62(3):387-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunitake H, Hodin R, Shellito PC, Sands BE, Korzenik J, Bordeianou L. Perioperative treatment with infliximab in patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis is not associated with an increased rate of postoperative complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(10):1730-1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bregnbak D, Mortensen C, Bendtsen F. Infliximab and complications after colectomy in patients with ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(3):281-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coquet-Reinier B, Berdah SV, Grimaud JC, et al. . Preoperative infliximab treatment and postoperative complications after laparoscopic restorative proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: a case-matched study. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(8):1866-1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eshuis EJ, Al Saady RL, Stokkers PC, Ponsioen CY, Tanis PJ, Bemelman WA. Previous infliximab therapy and postoperative complications after proctocolectomy with ileum pouch anal anastomosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(2):142-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mor IJ, Vogel JD, da Luz Moreira A, Shen B, Hammel J, Remzi FH. Infliximab in ulcerative colitis is associated with an increased risk of postoperative complications after restorative proctocolectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51(8):1202-1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Narula N, Charleton D, Marshall JK. Meta-analysis: peri-operative anti-TNFα treatment and post-operative complications in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37(11):1057-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang Z, Wu Q, Wang F, Wu K, Fan D. Meta-analysis: effect of preoperative infliximab use on early postoperative complications in patients with ulcerative colitis undergoing abdominal surgery. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36(10):922-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Z, Wu Q, Wu K, Fan D. Meta-analysis: pre-operative infliximab treatment and short-term post-operative complications in patients with ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31(4):486-492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selvaggi F, Pellino G, Canonico S, Sciaudone G. Effect of preoperative biologic drugs on complications and function after restorative proctocolectomy with primary ileal pouch formation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(1):79-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.El-Hussuna A, Theede K, Olaison G. Increased risk of post-operative complications in patients with Crohn’s disease treated with anti-tumour necrosis factor α agents—a systematic review. Dan Med J. 2014;61(12):A4975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kasparek MS, Bruckmeier A, Beigel F, et al. . Infliximab does not affect postoperative complication rates in Crohn’s patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18(7):1207-1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenfeld G, Qian H, Bressler B. The risks of post-operative complications following pre-operative infliximab therapy for Crohn’s disease in patients undergoing abdominal surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7(11):868-877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Matsuoka H, et al. . Risk factors for surgical site infection and association with infliximab administration during surgery for Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(10):1156-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang ZP, Hong L, Wu Q, Wu KC, Fan DM. Preoperative infliximab use and postoperative complications in Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2014;12(3):224-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nelson R, Liao C, Fichera A, Rubin DT, Pekow J. Rescue therapy with cyclosporine or infliximab is not associated with an increased risk for postoperative complications in patients hospitalized for severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(1):14-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gu J, Remzi FH, Shen B, Vogel JD, Kiran RP. Operative strategy modifies risk of pouch-related outcomes in patients with ulcerative colitis on preoperative anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(11):1243-1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang DH, Armstrong EP, Lee JK. Cost-utility analysis of biologic treatments for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. Pharmacotherapy. 2012;32(6):515-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riegler G, Tartaglione MT, Carratú R, et al. . Age-related clinical severity at diagnosis in 1705 patients with ulcerative colitis: a study by GISC (Italian Colon-Rectum Study Group). Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45(3):462-465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park MD, Bhattacharya J, Park K. Differences in healthcare expenditures for inflammatory bowel disease by insurance status, income, and clinical care setting. PeerJ. 2014;2:e587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]