Abstract

Given the increased trend in substance use patterns among Latina adolescents in recent years, the need for research that identifies gender-specific and culturally relevant protective factors is essential in tailoring interventions. The current study examined the links between marianismo gender role attitudes, ethnic identity, and substance use abstinence among 277 low-income Mexican American early adolescent girls. Mental health was also examined as a potential moderator in these links. Results of linear regression analysis revealed that familismo, virtuous/chaste, and spiritual marianismo gender role attitudes were predictive of stronger ethnic identity; conversely, self-silencing marianismo attitudes were predictive of weaker ethnic identity. Second, results of hierarchical logistic regressions revealed that both virtuous/chaste marianismo gender role attitudes and mental health (low rates of psychological distress) were inversely linked with substance use; furthermore, they had a combined link that was related to even lower rates of substance use among participants. However, ethnic identity did not have a direct or moderating effect on substance use. Findings suggest that the promotion of positive components of marianismo and mental health may have a protective effect against early substance use in Mexican American early adolescent girls.

Keywords: Early adolescent girls, ethnic identity, marianismo gender role attitudes, Mexican American, substance use

Introduction

Patterns of substance use among Latina adolescents have changed significantly in the past two decades (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [DHHS], 2011). Latina adolescents now engage in higher rates of substance use compared to their African American and European American female counterparts (47.6% lifetime marijuana use compared to 45% for African American girls and 34.8% for European American girls; 75.6% lifetime alcohol use compared to 66.8% for African American girls and 66.6% for European American girls; Kann et al., 2014). Rates of early alcohol initiation (alcohol use before the age of 13) are likewise elevated for Latina adolescents (20.2% compared to 18.7% for African American girls and 13.8% for European American girls), with a similar pattern of early-initiation marijuana use (9.8% compared to 6.1% for African American girls and 4.5% for European American girls; Kann et al., 2014). Rates of cigarette use for Latina girls, on the other hand, are similar to those of European American girls (41.4% for Latina adolescents, 41% for European American girls, and 31.7% for African American girls; Kann et al., 2014).

Early involvement in substance use is significantly correlated with negative educational and health outcomes among Latina youth (e.g., dropping out of high school, poor mental health, STIs/HIV/AIDS; Helfrich & McWey, 2014; Stueve & O’Donnell, 2005). This is particularly true for Latina youth who are continuously exposed to adverse environments and circumstances (e.g., low-income communities, discrimination; Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Lopez-Viets, Aarons, Ellingstad, & Brown, 2004). Evidence suggests that Latina early adolescents may be more susceptible than other adolescent ethnic groups to substance use risk as they endorse significantly more negative peer associations (i.e., higher reported proportion of friends participating in a variety of deviant behaviors) and are more likely to believe that refusing peer pressure to engage in deviant behavior would have negative consequences (Bámaca & Umaña-Taylor, 2006; Padilla-Walker & Bean, 2009).

In response to reports of increased substance use among Latina adolescents, a number of studies have examined substance use etiology and risk factors in this population (Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Elkington, Bauermeister, & Zimmerman, 2010; Gil, Wagner, & Tubman, 2004; Williams & Chang, 2000). In particular, low-income Latina youth often contend with limited resources related to economic disadvantage (Booth & Anthony, 2015; Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2013), racial/ethnic discrimination (Sanchez, Whittaker, Hamilton, & Zayas, 2015), and increased exposure to violence and/or criminality (Fagan, Wright, & Pinchevsky, 2014). In addition, Latina youth are at risk for a multitude of psychological stressors related to culture-specific challenges, such as acculturative stress and intergenerational conflict (Phinney, Ong, & Madden, 2000; Kessler, Avenevoli, & Merikangas, 2001). For example, national statistics show that Latina youth report higher rates of psychological distress (e.g., depression and anxiety) during early adolescence compared to European American and African American adolescents (11.4% compared to 10.9% for European Americans and 8.6% for African Americans; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2014). Moreover, compared to Latino adolescents, Latina adolescents reported greater depressive and anxiety symptoms (32.2% compared to 11.5%; Saluja et al., 2004; SAMHSA, 2014; Zayas, Lester, Cabassa, & Fortuna, 2005).

Given the significant risk factors and severe negative health outcomes associated with early adolescent substance use, more research is warranted to identify culturally relevant protective factors during early adolescence, before substance use becomes common and when attitudes and behaviors are most malleable to change (Burrow-Sánchez, Minami, & Hops, 2015; Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Rodgers, Nichols, & Botvin, 2011). The current study utilized an intersectionality framework (Cole, 2009) for examining the links between marianismo gender role attitudes, ethnic identity, mental health, and substance use abstinence among a low-income early adolescent Mexican American female sample. The intersectionality framework asserts the importance of examining the intersection of social position variables (e.g., ethnicity, social class, gender) at the core of theoretical formulation of ethnic minority youth development (Cole, 2009; García Coll et al., 1996; Shields, 2008). Furthermore, it takes into account the collective effect of multiple identities (e.g., the intersection of one’s ethnicity and gender) on individual experience and outcomes (Cole, 2009).

In the current study, we examined the intersectionality of gender role attitudes and ethnic identity among low-income Mexican American adolescent girls. Both gender-role attitudes and ethnic identity represent social categories in which Latina youth claim membership, as well as categories to which personal and psychological meaning are ascribed. Their intersections may create either advantage or disadvantage as it relates to substance use. We utilized an important gender-based Latina construct— marianismo—which reflects multiple and distinct behavioral expectations for Latinas based on culture (Castillo, Perez, Castillo, & Ghosheh, 2010), which may serve as risk or protective factors against substance use. The variability of marianismo gender role attitudes among Latina early adolescents is particularly relevant to the current study as the increased pressure to conform to culturally sanctioned gender roles is theorized to be an underlying factor in the emergence of gender differences in ethnic identity development and psychological functioning among Latinas (e.g., academic, school achievement, sex attitudes, etc.; Priess, Lindberg, & Hyde, 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010). Thus, an examination of the ways in which marianismo gender role attitudes are linked to ethnic identity and substance use behaviors may be helpful for targeting future research and interventions.

Marianismo gender role attitudes

Gender role attitudes are an important aspect of gender socialization and gender identity development and have a complex relationship with health and well-being (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004; Scott et al., 2015). Gender has been identified as a basic organizing feature of family life in many Latino families, with distinct gender-role expectations for men and women (Arciniega, Anderson, Tovar-Blank, & Tracey, 2008; Azmitia & Brown, 2002; Castillo et al., 2010; Cauce & Domenech-Rodriguez, 2002). For example, the cultural norm of machismo emphasizes that Latino males take a larger role in activities outside of the family (e.g., work, sports, etc.) and be virile, dominant, and independent (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004). By contrast, Latinas are expected to fulfill cultural norms related to marianismo, which emphasizes the centrality of family (e.g., being home centered and partaking in caretaking duties) and being submissive, chaste, and dependent (Castillo et al., 2010; Upchurch, Aneshensel, Mudgal, & McNeely, 2002).

Castillo et al. (2010) conceptualize marianismo as comprising five dimensions or pillars. The family pillar emphasizes the importance of a woman’s role in maintaining family cohesion (Castillo et al., 2010). The virtuous/chaste pillar describes how a Latina is expected to avoid bringing shame to the family by maintaining her virginity until marriage. The subordinate to others pillar reflects the belief that Latinas should show obedience and respect for the Latino hierarchical family structure, particularly toward men and elders (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004). The self-silencing to maintain harmony pillar reflects the belief that Latinas should keep confrontation and discomfort to a minimum within interpersonal relationships (Castillo & Cano, 2007). Finally, the spiritual pillar describes the belief that Latinas should be the spiritual leaders of the family and responsible for the religious education of their families.

The family and spiritual marianismo pillars are theorized to reflect “positive aspects” of marianismo that may be protective against depressive symptoms and promote academic resilience. Extant research has shown that familismo and spiritual marianismo pillars were correlated with fewer depressive symptoms (Cupito, Stein, & Gonzalez, 2015) and academic motivation and achievement among adolescent Mexican American Latinas (Rodriguez, Castillo, & Gandara, 2013). Conversely, the virtuous/chaste, subordinate to others, and self-silencing pillars are purported to be “negative aspects” of marianismo, and have been associated with depression (Perez, 2011) and poor academic outcomes among Latina adolescents (Rodriguez et al., 2013).

There is no research to date that directly examines the link between marianismo gender role attitudes and substance use behaviors among early adolescent Latinas. However, an examination of this relationship may be useful for illuminating the aspects of marianismo that may serve as potential risk or protective factors for substance use. For example, familismo cultural values and spiritual beliefs may be linked with better mental health, which may protect against substance use. Moreover, the expectation for early adolescent Latina girls to stay closer to family and respect the rules set for them by their parents (e.g., subordination to others) may lead to more time spent in the home, which may limit exposure to risk behaviors. Furthermore, the expectation that girls maintain “purity” and respect for their bodies and avoid bringing shame to their families (virtuous/chaste pillar) may also be related to less substance use among Mexican American preadolescent girls (Williams, Alvarez, & Andrade Hauck, 2002).

On the other hand, “negative” gender role expectations (e.g., self-silencing) may serve as risk factors for substance use among Latina adolescent girls. In particular, self-silencing marianismo attitudes may be linked to psychological distress (Rodriguez et al., 2013), which may lead girls to engage in substance use as a coping mechanism. In addition, the collective emphasis associated with the subordinate to others pillar may lead girls to place the needs of others whom they deem important (namely their peers) before themselves with regard to substance use (Deardorff, Tschann, Flores, & Ozer, 2010). As a result, girls may refrain from speaking up when offered illicit substances so as not to alienate, or cause conflict with, peers.

Ethnic identity

Ethnic identity development is another important aspect of normative development for ethnic minority adolescents that may be intricately linked to marianismo gender role attitudes (Kulis, Marsiglia, Kopak, Olmsted, & Crossman, 2012; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014) and may affect substance use behaviors. During adolescence, the process of ethnic identity development—one’s sense of belonging, attachment, and involvement in the cultural and social practices of his or her ethnic group (Phinney & Ong, 2007)—begins to emerge through maturing cognitive skills (e.g., abstract thinking and introspection) and social experiences outside of the home (e.g., peer relationships, dating, sports teams; Phinney & Ong, 2007). During this period, there is often a shift from familial to peer influence on cultural values, particularly regarding social behaviors (e.g., dating, drinking; Rivas-Drake, Hughes, & Way, 2009).

Phinney (1989) conceptualized ethnic identity as consisting of two central stages. Ethnic identity exploration is defined as the initial component of the ethnic identity developmental process by which an individual actively questions and examines what it means to be a member of the ethnic group. Ethnic identity commitment consists of an individual’s strong attachment or sense of belonging to the ethnic group (Phinney & Ong, 2007). The developmental trajectory of ethnic identity development is influenced by contextual factors including family, peer, school, and media influences (Else-Quest & Morse, 2014). A strong connection to one’s ethnic group is theorized to serve as a promotive factor among youth of color, including Latino youth, that buffers against adverse social conditions (e.g., acculturative stress and poverty) associated with their ethnic minority status (Love, Yin, Codina, & Zapata, 2006; Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2007; Unger, Ritt-Olson, Soto, & Baezconde-Garbanati, 2009). Thus, a positive view of one’s own ethnic group may promote a sense of resilience against these acculturative stressors and pressures to engage in risk behaviors that are prevalent during adolescence (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Marsiglia, Kulis, & Hecht, 2001).

Studies have shown that positive ethnic identity development is linked to psychological well-being, a sense of belonging, self-esteem, and prosocial attitudes (Neblett, Rivas-Drake, & Umaña-Taylor, 2012; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2012), as well as positive educational outcomes and academic success in Latina adolescents (Supple, Ghazarian, Frabutt, Plunkett, & Sands, 2006). However, studies examining the relationship between ethnic identity and substance use have produced mixed findings (Kulis et al., 2012). For example, some have found a positive link between ethnic identity and substance use, including cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use among Latino/a (and African American) early adolescents (Marsiglia, Kulis, Hecht, & Sills, 2004; Zamboanga, Schwartz, Jarvis, & Van Tyne, 2009). Others have found a negative link between ethnic identity and substance use in Latino early adolescents (Kulis et al., 2012).

Judging from previous research, it appears that examining ethnic identity alone may not be sufficient to reach meaningful conclusions about cultural correlates related to substance use in Latina early adolescents. Furthermore, it appears the relationship between ethnic identity and substance use for Latino adolescents has consistently varied by gender (Kulis et al., 2012; Marsiglia et al., 2004). For example, Kulis et al. (2012) found that ethnic identity was a more consistent buffer against substance use for Mexican American early adolescent boys than for girls. Given these findings, we examine both marianismo gender role beliefs and ethnic identity with the hopes of further elucidating factors related to substance use in early adolescent Latinas. Latina youth may undergo particular culturally gendered experiences that preclude strong ethnic identity from having the same protective effect against substance use that it does for Latino boys.

Mental health

Mental health may also play an important role in the link between marianismo gender role attitudes, ethnic identity, and substance use in Mexican American early adolescent girls. Substance use and mental health problems frequently co-occur in adolescence (Elkington et al., 2010; Gil et al., 2004), and substance use is particularly common among youth suffering psychological distress (i.e., depression and anxiety; Armstrong & Costello, 2002; Brook, Brook, Zhang, Cohen, & Whiteman, 2002). Early adolescents, particularly those struggling with psychological distress (e.g., anxiety and depression), may be more vulnerable to engaging in substance use compared to older adolescents due to factors such as underdeveloped planning and problem-solving abilities and greater influence by peer processes (Pedlow & Carey, 2004). In particular, youth may use substances as a way to self-medicate or alleviate symptoms of depression and anxiety (Elkington et al., 2010).

Latina adolescents may be at an especially elevated risk for mental health problems compared to other adolescent ethnic groups (Mulye et al., 2009). In particular, they report higher levels of depressive symptoms and are more likely to engage in suicidal behavior than other groups (Zayas et al., 2005). Culture-specific challenges such as acculturative stress and intergenerational conflict between Latina youth and parents have been proposed as contributing to these lower rates of psychological well-being (Phinney et al., 2000; Zayas & Pilat, 2008). Given that mental health has been associated with marianismo gender role attitudes, ethnic identity, and substance use, its inclusion as a moderator in the current study is warranted as it may account for additional variability in the links between marianismo gender role attitudes, ethnic identity, and substance use.

The current study

Given the changing trends in substance use patterns among early adolescent Latinas, understanding the role of gender and cultural factors in substance use behaviors may help identify youth at greatest risk for substance use. This, in turn, may inform the design of effective substance abuse interventions that are culturally relevant and focus on mental health needs of early adolescent Latina youth. Our study makes the following unique contributions to the substance abuse literature. First, we focus on the unique experiences of a specific Latina adolescent subgroup, Mexican American early adolescent girls, allowing for a more nuanced examination of within-group differences rather than treating individuals from different Latina ethnic backgrounds as a single monolithic group. Similar to other immigrant groups where recent immigration is a common family experience, many Mexican-origin youths find themselves acculturating to U. S. society during the most formative years of their lives (Kulis et al., 2011). During early adolescence, they also enter a sensitive period when factors preceding actual substance use, such as pro-drug attitudes and norms, positive expectations about substance use, and intentions to use them, begin to emerge (Elek, Miller-Day, & Hecht, 2006). Thus, understanding their unique risk and protective factors is essential to tailoring interventions.

Second, the distinct socialization practices in Mexican American families suggest that girls may experience and interpret gender norms in unique ways, particularly as they negotiate the norms within their families of origin and the mainstream U.S. culture (Castillo et al., 2010; Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004; Williford, 2011). Accordingly, their interpretation and internalization of marianismo values may be linked to their ethnic identity, which is also developing by the start of adolescence (Kulis et al., 2012). These intersecting influences of gender and ethnic identity development may affect low-income Mexican American adolescent girls’ attitudes and behaviors toward substance use. As such, an important goal of the current study was to examine the extent to which marianismo gender role attitudes are related to ethnic identity and their link to substance use in low-income early adolescent Mexican American female youth. Focusing on marianismo gender role attitudes allows for a more nuanced examination of how gender-based cultural expectations may be linked with ethnic identity, and together, substance use.

Finally, given that mental health (i.e., psychological distress—anxiety and depression) has been associated with both marianismo gender role attitudes and ethnic identity among Latina adolescent populations (Cupito et al., 2015; Perez, 2011; Rodriguez et al., 2013), we examined whether mental health moderated the links between marianismo gender role attitudes, ethnic identity, and substance use behaviors (i.e., greater psychological distress may exacerbate the effect of “negative marianismo” pillars on substance use risk).

Specifically, we addressed the following research questions: (a) What is the nature of the relationship between the five pillars of marianismo and ethnic identity among low-income early adolescent Mexican American girls? (b) What is the magnitude of the relationship between marianismo, ethnic identity, and mental health, respectively, and total lifetime substance use (cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana)? (c) Is the relationship between marianismo and substance use moderated by ethnic identity? (d) Is the relationship between marianismo and substance use moderated by mental health?

Method

Participants

During the 2012–2013 academic year, two middle schools serving sixth through eighth grades in Central Texas were identified for participant recruitment. The schools in the study were selected by means of convenience, as they enroll from primarily low-income Mexican-origin neighborhoods. Participants included 277 Mexican American early adolescent females. The participants ranged in age from 11 to 14 years (M = 12.58 years, SD = 0.97). Participant grade levels were as follows: 36.5% (n = 101) 6th grade, 29.6% (n = 82) 7th grade, and 33.9% (n = 74) 8th grade. Of the total participant pool, 9% (n = 25) were first generation (were not born in the United States), 71.1% (n = 197) were second generation (i.e., born in the United States to immigrant parents), 12.6% (n = 35) were third generation, and 7.2% (n = 20) were fourth generation or beyond. Approximately 98%–99% of participants were considered socioeconomically disadvantaged according to their enrollment addresses, and over 95% were eligible for the free lunch program.

Procedure

After obtaining university IRB approval as well as approval from the school district, the first author worked closely with the school counselors, who identified all girls’ advisory classrooms from sixth to eighth grades for participant recruitment. These classrooms were visited by the first author to explain the study and distribute parental consent forms (one side in English and one side in Spanish). These forms were taken home by students for their parents/guardians to sign. The consent forms were collected by the school counselors in their advisory periods and given to the researcher approximately 2 weeks before survey administration. Surveys were available in English and Spanish, and students were asked for their language preference before filling out the survey. All students requested to fill out the survey in English. The students were reminded that their participation was voluntary and that the results from their questionnaire would remain confidential. The survey time ranged from 35 to 40 minutes, and upon completion the participants were given a $5 gift card.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire asked the participants to indicate their age, gender, ethnicity, grade level, and immigrant generation. The U.S. Census criterion for categorizing generation status was used in the current study. Students were asked which of their family members were the first to be born in the United States. Those students that indicated that they were not born in the United States were coded as “first generation.” Students who indicated that they were the first to be born in the United States were coded as “second generation.” Students who indicated that their parents were the first to be born in the United States were coded as “third generation.” Those who indicated that their grandparents were born in the United States were coded as “fourth generation,” and those who indicated that their great-grandparents were born in the United States were coded as “beyond fourth generation.”

Marianismo beliefs scale

The Marianismo Beliefs Scale (Castillo et al., 2010) was designed to assess the extent to which a Latina believes she should participate in traditional gender role expectations. This 24-item measure consists of five subscales or pillars: family (five items, e.g., “A Latina must be a source of strength for her family”), virtuous and chaste (5 items, e.g., “A Latina should remain a virgin until marriage”), subordinate to others (five items, e.g., “A Latina should do anything a male in the family asks her to do”), silencing self to maintain harmony (six items, e.g., “A Latina should feel guilty about telling people what she needs”), and spiritual (three items, e.g., “A Latina should be the spiritual leader of the family”). The items are rated along a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. The score is calculated as the mean of items in each subscale or of the scale as a whole. Higher scores indicate greater adherence to marianismo beliefs. Cronbach’s alpha for the current study is .75 for the family pillar, .71 for the virtuous/chaste pillar, .75 for the subordinate to others pillar, .70 for the self-silencing pillar, and .84 for the spiritual pillar.

Multigroup ethnic identity measure – revised

This 12-item revised Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) scale (Roberts et al., 1999) is used to assess different aspects of ethnic identity, including ethnic exploration (five items; extent to which one has considered the subjective meaning of one’s ethnicity) and ethnic identity commitment/affirmation (seven items; extent to which one feels positively about one’s ethnic group) among diverse young adolescents. Participants rate their agreement/disagreement with each statement on a 4-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. Higher scores are indicative of a higher level of ethnic identity. Sample items include “I think a lot about how my life will be affected by my ethnic group membership” (exploration) and “I am happy that I am a member of the ethnic group I belong to” (commitment). Respondents can obtain a score on the exploration and commitment subscales as well as a total score, which are determined by calculating the mean of each subscale’s item ratings. The structure and construct validity of the MEIM was conducted among young adolescents from diverse ethnic groups, and factor analysis yielded a two-factor structure that corresponded to Phinney’s theoretical approach to ethnic identity (Phinney, 1992). Cronbach’s alpha for the total ethnic identity scale was .81.

Substance use

Three items from the alcohol and other drug portions of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey were used to assess lifetime substance use behaviors (Eaton et al., 2012). Specifically, lifetime cigarette use, lifetime marijuana use, and lifetime alcohol use were measured. Lifetime use was measured rather than past 30-day usage to capture low as well as high-frequency behaviors. Students responded yes or no to the following questions: “Have you ever (a) drank alcohol (not including at church), (b) smoked cigarettes, or (c) used marijuana?” A composite total substance use score was created combining participants’ scores on cigarette, marijuana, and alcohol use as follows: 3 = tried all three substances; 2 = tried two substances; 1 = tried one substance; and 0 = never tried any substance. Thus, higher scores indicate greater number of lifetime substances used.

Analytic strategy

To address our first research question, we conducted a multiple linear regression analysis with the five marianismo pillars (family, virtuous/chaste, subordinate to others, self-silencing, and spiritual) as predictors and ethnic identity as the outcome variable, controlling for age and immigrant generation. To address our remaining research questions, we conducted ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions with number of substances ever used as the outcome variable. Predictors included the five marianismo pillars, ethnic identity, and mental health. Interaction terms were created for each marianismo pillar and the ethnic identity total score by centering each variable around its mean and using the product of the centered variables (Aiken, West, & Reno, 1991). Interaction terms were also created for each marianismo pillar and the total mental health score. Regressions were conducted in two steps. In the first step, covariates and main effects were tested. In the second step, interactions were examined for variables with significant main effects in Step 1. Age and immigrant generation were treated as covariates in all analyses. However, because immigrant generation was not significantly related to lifetime number of substances used, model results are presented with immigrant generation omitted from the model. We did not control for socioeconomic status (SES) due to sample homogeneity; the majority of students enrolled in the participating schools were considered socioeconomically disadvantaged according to their enrollment addresses (98%–99%) and their eligibility for the free lunch program (over 95%). All analyses were conducted in Stata MP 14.2.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive analyses (i.e., percentages/means, standard deviations, and skewness) of the continuous predictors (i.e., marianismo subscales, mental health, and ethnic identity scales) were used to check the data for normality, input errors, and outliers (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics for all variables). No unusual occurrences were found in the data. Less than 1% of the data was missing among participants on any one variable. One participant was dropped from the analysis due to missing covariate data. Because such a small amount of missingness was recorded among the data, the estimates should not be biased (Allison, 2001). Given that substance use behaviors are indicative of nonnormally distributed data (Onwuegbuzie & Daniel, 2002), a nonparametric procedure, Spearman’s correlation coefficient (i.e., Spearman’s rho) was performed instead of Pearson’s correlation. These findings are presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of study variables (N = 277).

| Demographic statistics | N | % | Scale statistics | M | SD | Range | α | Skewness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Predictor variables | ||||||||

| 11 | 45 | 16.2% | Familismo | 3.25 | 0.42 | 1–4 | .75 | −0.14 | |

| 12 | 78 | 28.2% | Virtuous/chaste | 2.95 | 0.61 | 1–4 | .71 | −0.30 | |

| 13 | 102 | 36.8% | Subordinate to others | 2.12 | 0.64 | 1–4 | .75 | 0.41 | |

| 14 | 52 | 18.8% | Self-silencing | 2.20 | 0.55 | 1–4 | .70 | 0.15 | |

| Spiritual | 2.76 | 0.72 | 1–4 | .84 | −0.33 | ||||

| Grade | Ethnic Identity | 2.95 | 0.53 | 1–4 | .81 | −0.48 | |||

| 6th | 101 | 36.5% | Mental Health | 68.26 | 13.07 | 0–100 | .88 | −0.48 | |

| 7th | 82 | 29.6% | |||||||

| 8th | 94 | 33.9% | Outcome variable | ||||||

| Lifetime number of substances used | .81 | 1.05 | 0–3 | 0.86 | |||||

| Immigrant generation | |||||||||

| First generation | 25 | 9.0% | |||||||

| Second generation | 197 | 71.1% | |||||||

| Third generation | 35 | 12.6% | |||||||

| Fourth generation | 10 | 3.6% | |||||||

| Fifth generation | 10 | 3.6% | |||||||

| Substance use | |||||||||

| Lifetime cigarette use | 48 | 17.3% | |||||||

| Lifetime marijuana use | 77 | 27.8% | |||||||

| Lifetime alcohol use | 99 | 35.7% | |||||||

SD = standard deviation.

Table 2.

Spearman’s correlations for ethnic identity, marianismo pillars, and substance use for mexican american early adolescent girls (N = 277).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | 1 | |||||||||

| 2. Immigrant generation | −.04 1 | |||||||||

| 3. Ethnic identity | −.09 | −.09 | 1 | |||||||

| 4. Family | −.07 | −.06 | .13* | 1 | ||||||

| 5. Virtuous/chaste | .06 | −.09 | .47** | .23** | 1 | |||||

| 6. Subordinate | −.15* | .03 | .39* | .31** | .30** | 1 | ||||

| 7. Self-silencing | −.21** | −.01 | .05 | .56** | .24** | .37** | 1 | |||

| 8. Spiritual | −.01 | .02 | .45** | .11 | .41** | .45** | .10 | 1 | ||

| 9. Mental health | −.20** | .05 | .27** | .04 | .18** | .10 | .02 | .19** | 1 | |

| 10. Substance use | .26** | −.04 | −.14* | −.12* | −.26** | −.09 | −.16** | −.10 | .35** | 1 |

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001.

Main findings

The results of the multiple regression analysis predicting ethnic identity from the five marianismo pillars are presented in Table 3. The overall model was significant, accounting for 36% of the variance in ethnic identity scores among early adolescent Latinas. An analysis of the beta weights in the regression analyses shows that scores on the family, virtuousness, and spirituality pillars of marianismo were significantly and positively related to ethnic identity. However, the self-silencing marianismo pillar was significantly and negatively related to ethnic identity (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Linear regression results predicting ethnic identity from five marianismo pillars (N = 277).

| Predictor: | Main effects

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1

| ||||

| B | SE | |||

| Marianismo pillars | ||||

| Age | −.96 | .33 | −.15 | ** |

| Family | .68 | .18 | .22 | *** |

| Virtuous/chaste | .62 | .12 | .29 | *** |

| Subordinate | .18 | .12 | .09 | |

| Silence | −.44 | .12 | −.22 | *** |

| Spirituality | .82 | .18 | .28 | *** |

| Model-adjusted R2 | .35 | |||

| Model F (df) | 25.37 (6,270)*** | |||

df = degreed of freedom.

p < .01;

p < .001.

Results of the OLS regression analyses predicting lifetime number of substances used are presented in Table 4. Findings show that there were significant main effects for the virtuous/chaste marianismo pillar and mental health. Neither ethnic identity nor any of the other marianismo pillars were significantly related to lifetime number of substances used. Both virtuous/chaste marianismo and mental health were negatively related to lifetime number of substances used, indicating that higher scores on virtuous/chaste marianismo and mental health, respectively, were related to reporting using fewer substances among early adolescent Latinas (see Table 4, Step 1).

Table 4.

Logistic regression results predicting number of substances ever tried (N = 277).

| Predictor | Main effects | Interactions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Step 1

|

Step 2

|

|||||||

| B | SE | β | B | SE | β | |||

| Marianismo pillars | ||||||||

| Age | .24 | .06 | .22 | *** | .23 | .06 | .22 | *** |

| Family | −.01 | .03 | −.01 | −.01 | .03 | −.01 | ||

| Virtuous/chaste | −.08 | .02 | −.25 | *** | −.26 | .09 | −.78 | *** |

| Subordinate | −.01 | .02 | −.03 | −.01 | .02 | −.02 | ||

| Silence | −.01 | .02 | −.02 | −.01 | .02 | −.03 | ||

| Spirituality | .01 | .03 | .02 | .01 | .03 | .03 | ||

| Ethnic identity | .01 | .01 | .06 | .01 | .01 | .06 | ||

| Mental health | −.02 | .01 | −.28 | *** | −.06 | .02 | −.77 | *** |

| Virtuousness × Mental health | .002 | .001 | .79 | *** | ||||

| Model-adjusted R2 | .19 | .20 | ||||||

| Model F (df) | 8.95 (8,267)*** | 8.53 (9,266)*** | ||||||

df = degrees of freedom.

p < .001.

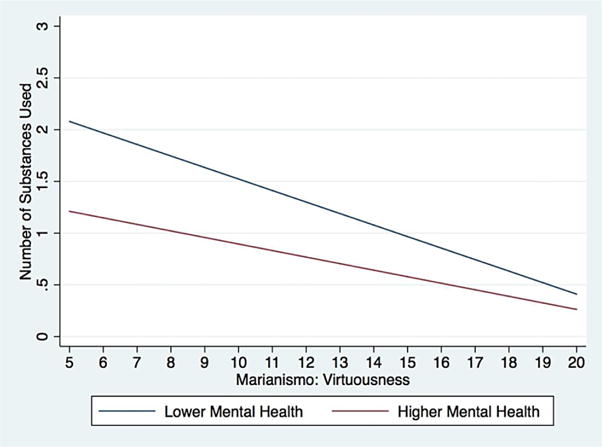

Drawing on the significant main effects, we examined the interaction between virtuousness and mental health, which was significantly related to lifetime number of substances used (see Table 4, Step 2). Because ethnic identity was not significantly related to lifetime number of substances used, we did not follow up the main effect analyses with analyses of interactions between ethnic identity and any marianismo pillar. Figure 1 presents follow-up analyses of predicted probabilities for number of lifetime substances used based on the interaction between mental health and virtuous/chaste marianismo. These analyses revealed that for early adolescent Latinas, virtuous/chaste marianismo interacted with mental health to provide an additional protective effect with respect to lifetime number of substances used. Specifically, early adolescent Latinas scoring higher on virtuous/chaste marianismo reported using fewer substances in their lifetime, with the effect being the strongest for girls scoring lower on mental health. It is interesting to note that as scores on virtuous/chaste marianismo increased, the more similar the predicted probabilities for lifetime number of substances used for Latinas with lower versus higher scores on mental health became. That is, at the highest levels of virtuous/chaste marianismo, the predicted probabilities for lifetime number of substances used for early adolescent Latinas scoring lower or higher on mental health converged. Thus, at the highest levels of virtuous/chaste marianismo, early adolescent Latinas with lower mental health had about the same probability of lifetime number of substances used as those with higher mental health.

Figure 1.

Moderating effect of mental health on the relationship between the virtuous/chaste marianismo pillar and lifetime number of substances used.

Discussion

Utilizing an intersectionality framework, this study is the first to examine the direct and combined links between marianismo gender role attitudes, ethnic identity, mental health, and substance use among a low-income Mexican American early adolescent female sample. Both gender role ideologies and ethnic identity development are cultural-contextual variables that are theorized to shape behaviors among Latina youth. Our findings provide a more nuanced understanding of the links between marianismo gender role attitudes and ethnic identity and their respective influences on substance use behaviors.

Marianismo gender role attitudes and ethnic identity

First, findings showed that marianismo gender role attitudes were inextricably linked with ethnic identity among this sample of low-income Mexican American early adolescent girls. Specifically, both family and spiritual marianismo pillars were significantly and positively linked with ethnic identity. This suggests that the interdependence of family and the importance and centrality of women as the spiritual pillars of the family may provide low-income Mexican American early adolescent girls with a positive reference system for ethnic group knowledge (Knight et al., 2011) and a strong sense of purpose and connection with their ethnic culture and identity (Falicov, 2013).

Second, our findings provide a more nuanced understanding of the role of “negative” marianismo gender role attitudes in the link to ethnic identity. In particular, the virtuous/chaste marianismo pillar—which describes how a Latina is expected to avoid bringing shame to her family by maintaining her virginity until marriage—was linked with a stronger ethnic identity. These findings were consistent with a prior study that showed a positive link between virtuous/chaste marianismo and ethnic identity (affirmation and commitment) among early adolescent Mexican American girls (Sanchez, Whittaker, Hamilton, & Arango, 2017). Perhaps Mexican American early adolescent girls may endorse virtuous/chaste attitudes to ensure positive acceptance from their family and greater ethnic identity fulfillment for “maintaining family honor.”

Conversely, the self-silencing marianismo pillar, which reflects the belief that Latina women should be all forgiving and not express their needs, was negatively related to ethnic identity. This indicates self-silencing may have a negative effect on how Mexican American early adolescent girls feel about their ethnic group membership (López & Chesney-Lind, 2014). In particular, the pressure to place the concern of others out of the desire to preserve interpersonal relationships, may serve as a barrier to positive ethnic identity development among Mexican American girls.

Marianismo, ethnic identity, mental health, and substance use behaviors

Second, findings showed that virtuous/chaste marianismo attitudes were significantly linked to lower rates of substance use, suggesting a compensatory function of this pillar regarding substance use behaviors. These findings are consistent with prior research that found an inverse link between virtuous/chaste marianismo beliefs and other risk behaviors such as prosexual attitudes and sexual behaviors among early adolescent Mexican American girls (Sanchez et al., 2015). Among many Latina/o families, the expectation that girls “maintain family honor” and “respect their body” is strongly reinforced through family socialization and peer relationships (Deardorff et al., 2010). This is often reflected in the stricter supervision of girls, including less freedom to engage in risk behaviors outside of the home (Williams et al., 2002). This may result in less access to risky peers and substance use in general. However, during late adolescence and early adulthood, when many Latinas have more autonomy from their families, the continued endorsement of virtuous/chaste values may be counterproductive (Moreno, 2007) as they may not openly talk about substance use or resist the pressure to engage in risky substance use behaviors (e.g., binge drinking) with peers and partners.

Third, findings showed that mental health also had a direct effect on substance use. In particular, girls who reported less psychological distress also reported less substance use. The link between mental health and substance use outcomes has been well established in the literature (Chen & Jacobson, 2012; Elkington et al., 2010; Gil et al., 2004). Mental health difficulties and substance use increase rapidly during adolescence and young adulthood (Kessler, 2004), and depression and anxiety are among the most common mental health difficulties faced by Latina youth (Helfrich & McWey, 2014; Kann et al., 2014). Early adolescents, particularly those struggling with psychological distress (e.g., anxiety and depression), may be more vulnerable to engaging in substance use compared to older adolescents due to factors such as underdeveloped planning and problem-solving abilities and greater influence by peer processes (Pedlow & Carey, 2004). This is particularly salient for Mexican American early adolescent girls as the research has shown that Latina youth often reported higher rates of psychological distress (e.g., depression and anxiety) compared to Latino boys and youth from other ethnic groups (Helfrich & McWey, 2014; Kann et al., 2014). Thus, promoting increased mental health is very important in buffering against substance use.

Finally, findings suggest that virtuous/chaste marianismo gender role attitudes and mental health had a collective effect on substance use behaviors. In particular, virtuous/chaste marianismo gender role attitudes contributed to lower rates of substance use among girls who also endorsed lower levels of psychological distress. This suggests that the combination of virtuous/chaste marianismo gender role attitudes and mental health provided an additional protective effect against early adolescent substance use behaviors. Because the virtuous/chaste marianismo pillar has been previously linked to negative psychosocial outcomes among Latina adolescents (Perez, 2011; Rodriguez et al., 2013), it may be that it is interpreted or internalized differently (i.e., respect for one’s body versus sexual subjugation) among youth with healthy psychological reserves compared to those without.

Surprisingly, ethnic identity was not linked to substance use behaviors among this sample of Mexican American early adolescent girls. Although ethnic identity has been linked to psychological well-being, self-esteem, and positive educational outcomes among early adolescent Latinas, findings have been mixed with regard to substance use (Kulis et al., 2012). For example, Kulis et al. (2012) found that ethnic identity was a more consistent buffer against substance use for Mexican American preadolescent boys than for girls. In fact, they found that among Mexican-heritage females living longer in the United States, stronger ethnic identity predicted undesirable changes in alcohol use, pro-drug norms, and peer substance use.

Ethnic identity is purported to emerge during adolescence as part of a developmental process that involves complex factors related to one’s self-concept (Phinney, 1992). A strong ethnic identity is characterized by the manner in which individuals interpret and understand their ethnicity (i.e., are knowledgeable about the values, social norms, and practices that characterize their ethnic group) and, most important, the degree to which they see themselves as members of their ethnic group (Phinney, 1996). Ethnic identity is also theorized to be shaped by forces in the immediate social context and environment where they spend much of their time, such as at home and in school (Kulis et al., 2012). Empirical evidence suggests that the ethnic composition within schools can affect the salience of ethnic identity among ethnic minority youth, which may have an effect on substance use behaviors. For example, when Latino adolescents are in a context where they constitute a numerical minority, they appear more in touch with their identity compared with their counterparts in the numerical majority (Umaña-Taylor, 2004). Thus, the buffering and promotive effect of ethnic identity may be more activated. On the other hand, in contexts where Latino adolescents constitute the numerical majority in their school and neighborhood environments—which is true for the current sample of low-income Mexican American early adolescent girls—they may retain a strong connection to their culture of origin but without a need to defend or explain it (Kulis, Marsiglia, Nieri, Sicotte, & Hohmann-Marriott, 2004). That is, they may be less likely to be challenged by peers from the dominant ethnic group or may face less intense ethnic discrimination (Umaña-Taylor, Vargas-Chanes, Garcia, & Gonzales-Backen, 2008). Thus, the protective or resilient factor of ethnic identity may not be activated in the same way.

Limitations and future directions

The results of the current study must be interpreted in the context of a few limitations. This study was correlational, and statistical analyses used to explore the relations between marianismo beliefs, ethnic identity, and substance do not establish causation. Given the cross-sectional nature of the study, we cannot draw definitive conclusions about the directionality of the relationships. The current study utilized a dichotomous measure (yes/no) to assess lifetime substance use. Future studies may want to measure frequency of substance use and most recent substance use to capture a more complex pattern of students who are actively engaging in substance use. Given the significantly high intercorrelation between ethnic identity exploration and commitment subscales (∼.70), the total ethnic identity score was used. However, future research should examine potential differences in the ethnic identity factor structure previously established in older adolescent Latina populations. This high intercorrelation could be due to differences in the populations in which these scales were developed (e.g., early adolescents versus adolescents, more recent immigrant generations versus later immigrant generations). It may be that early adolescents have limited vocabulary surrounding ethnic identity development, which may have restricted their understanding of items on the ethnic identity scale. However, among older adolescent populations, the various factors of ethnic identity may become more distinct due to advances in overall cognitive, social, and ego identity development. Further research should take caution to ensure the appropriate measurement of these constructs with early adolescent samples. Future studies should include longitudinal data to help support the temporal relationships among the variables as well as to provide a more comprehensive link between marianismo gender role attitudes, ethnic identity, mental health, and substance use in Latina adolescents across time. The sample for the current study consisted of Mexican American early adolescent girls living in low-income communities. Their experiences may differ from Mexican American adolescent girls from middle-class or higher SES backgrounds. Future studies should investigate how social class as a contextual factor influences substance use. Finally, future studies should also take into consideration additional cultural-contextual variables that may help better explain early adolescent substance use behaviors beyond marianismo gender role attitudes and mental health, such as acculturation, immigrant generation, and time spent in the United States (Kulis et al., 2012).

Implications

Overall, findings indicate that the multidimensional construct of marianismo was a useful construct for highlighting specific pillars that were directly linked to ethnic identity and those linked to substance use, which may be helpful for future research in this area. Specifically, it highlighted that “positive” marianismo pillars, such as familismo and spirituality, were positively linked with ethnic identity. It also highlighted virtuous/chaste marianismo gender role attitudes as having a significant compensatory effect against substance use. Given that only virtuous/chaste marianismo gender role attitudes were linked to substance use, future research may want to further examine the link between virtuous/chaste marianismo gender role beliefs and parent-child communication around substance use abstinence and self-efficacy regarding substance use communication with peers as a way to respect one’s body (Parsai, Voisine, Marsiglia, Kulis, & Nieri, 2008). It may be that the relationship between cultural/ethnic variables and substance use is better explained by more nuanced cultural socialization factors unique to Mexican and Mexican American families, such as marianismo pillars, rather than the greater concept of ethnic identity for Latina youth. Marianismo may hold more meaning for Latina youth at an earlier age, while ethnic identity becomes more salient in influencing psychosocial behaviors at a later point during adolescence. In terms of practical implications, utilizing participatory action research approaches that involve and centralize the voices of Latina youth in a collaborative process with researchers and community members to address marianismo gender role beliefs, ethnic identity, mental health, and substance use may prove a useful avenue toward challenging maladaptive gender role attitudes (e.g., self-silencing), fostering positive ethnic identity development, and empowering girls to make safer decisions and choices around substance use.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Population Research Center [Grant Number R24HD042849].

Footnotes

Color versions of one or more of the figures in the article can be found online at www.tandfonline.com/wesa.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Missing data. Vol. 136. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Arciniega GM, Anderson TC, Tovar-Blank ZG, Tracey TJ. Toward a fuller conception of Machismo: Development of a traditional Machismo and Caballerismo Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2008;55(1):19–33. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.55.1.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong TD, Costello EJ. Community studies of adolescent substance use, abuse or dependence and psychiatric comorbidity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1224–1239. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia M, Brown JR. Latino immigrant parents’ beliefs about the “path of life” of their adolescent children. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino Children and Families in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger Press; 2002. pp. 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bamaca MY, Umana-Taylor AJ. Testing a model of resistance to peer pressure among Mexican-origin adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2006;35(4):626–640. [Google Scholar]

- Booth JM, Anthony EK. Examining the interaction of daily hassles across ecological domains on substance use and delinquency among low-income adolescents of color. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2015;25:810–821. doi: 10.1080/10911359.2015.1027026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brook DW, Brook JS, Zhang C, Cohen P, Whiteman M. Drug use and the risk of major depressive disorder, alcohol dependence, and substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:1039–1044. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.11.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burrow-Sánchez JJ, Minami T, Hops H. Cultural accommodation of group substance abuse treatment for Latino adolescents: Results of an RCT. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2015;21(4):571–583. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Cano MA. Mexican American psychology: Theory and clinical application. In: Negy C, editor. Cross-cultural psychotherapy: Toward a critical understanding of diverse client populations. Reno, NV: Bent Tree Press; 2007. pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Perez FV, Castillo R, Ghosheh MR. Construction and initial validation of the Marianismo Beliefs Scale. Counselling Psychology Quarterly. 2010;23(2):163–175. doi: 10.1080/09515071003776036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cauce AM, Domenech-Rodriguez M. Latino families: Myths and realities. In: Contreras JM, Kerns KA, Neal-Barnett AM, editors. Latino children and families in the United States. Westport, CT: Praeger Press; 2002. pp. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen P, Jacobson KC. Developmental trajectories of substance use from early adolescence to young adulthood: Gender and racial/ethnic differences. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50(2):154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER. Intersectionality in research in psychology. American Psychologist. 2009;64(3):170–180. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupito AM, Stein GL, Gonzalez LM. Familial cultural values, depressive symptoms, school belonging and grades in Latino adolescents: Does gender matter? Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015;24(6):1638–1649. doi: 10.1007/s10826-014-9967-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deardorff J, Tschann JM, Flores E, Ozer EJ. Sexual values and risky sexual behaviors among Latino youths. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;42(1):23–32. doi: 10.1363/4202310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falicov CJ. Latino families in therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eaton DK, Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin S, Flint KH, Hawkins J, Wechsler H. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2011. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries. 2012;61(4):1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elek E, Miller-Day M, Hecht ML. Influences of personal, injunctive and descriptive norms on early adolescent substance use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2006;36:147–171. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington KS, Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA. Psychological distress, substance use, and HIV/STI risk behaviors among youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:514–527. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9524-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else-Quest NM, Morse E. Ethnic variations in parental ethnic socialization and adolescent ethnic identity: A longitudinal study. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2014;21:54–64. doi: 10.1037/a0037820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Wright EM, Pinchevsky GM. The protective effects of neighborhood collective efficacy on adolescent substance use and violence following exposure to violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43(9):1498–1512. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0049-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, García HV. An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development. 1996;67(5):1891–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil AG, Wagner EF, Tubman JG. Associations between early-adolescent substance use and subsequent young-adult substance use disorders and psychiatric disorders among a multiethnic male sample in South Florida. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(9):1603–1609. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfrich CM, McWey LM. Substance use and delinquency: High risk behaviors as predictors of teen pregnancy among adolescents involved with the child welfare system. Journal of Family Issues. 2014;35:1322–1338. doi: 10.1177/0192513×13478917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future: National survey results on drug use, 1975-2012 Volume I, secondary school students. Ann Arbor, MI: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, Flint KH, Kawkins J, Harris WA, Whittle L. Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 2013. MMWR Surveillance Summary. 2014;63(Supplement 4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R, Avenevoli S, Merikangas K. Mood disorders in children and adolescents: An epidemiologic perspective. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49(12):1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;56(10):730–737. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales NA, Ettekal I, Jaconis M, Boyd BM. The familial socialization of culturally related values in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2011;73(5):913–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Kopak AM, Olmsted ME, Crossman A. Ethnic identity and substance use among Mexican-heritage preadolescents: Moderator effects of gender and time in the United States. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2012;32(2):165–199. doi: 10.1177/0272431610384484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulis S, Marsiglia FF, Nieri T, Sicotte D, Hohmann-Marriott B. Majority rules? The effects of school ethnic composition on substance use by Mexican heritage adolescents. Sociological Focus. 2004;37:373–393. doi: 10.1080/00380237.2004.10571252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López V, Chesney-Lind M. Latina girls speak out: Stereotypes, gender and relationship dynamics. Latino Studies. 2014;12(4):527–549. doi: 10.1057/lst.2014.54. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Viets VC, Aarons GA, Ellingstad TP, Brown SA. Race and ethnic differences in attempts to cut down or quit substance use in a high school sample. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse. 2004;2:83–103. doi: 10.1300/J233v02n03_05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Love AS, Yin Z, Codina E, Zapata JT. Ethnic identity and risky health behaviors in school-age Mexican-American children. Psychological Reports. 2006;98:735–744. doi: 10.2466/pr0.98.3.735-744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Hecht ML. Ethnic labels and ethnic identity as predictors of drug use among middle school students in the Southwest. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11(1):21–48. doi: 10.1111/1532-7795.00002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Hecht ML, Sills S. Ethnicity and ethnic identity as predictors of drug norms and drug use among preadolescents in the US Southwest. Substance Use & Misuse. 2004;39:1061–1094. doi: 10.1081/ja-120038030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno CL. The relationship between culture, gender, structural factors, abuse, trauma, and HIV/AIDS for Latinas. Qualitative Health Research. 2007;17:340–352. doi: 10.1177/1049732306297387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulye TP, Park MJ, Nelson CD, Adams SH, Irwin CE, Jr, Brindis CD. Trends in adolescent and young adult health in the United States. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2009;45:8–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neblett EW, Jr, Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor AJ. The promise of racial and ethnic protective factors in promoting ethnic minority youth development. Child Development Perspectives. 2012;6:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00239.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie AJ, Daniel LG. Uses and misuses of the correlation coefficient. Research in the Schools. 2002;9(1):73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Padilla-Walker LM, Bean RA. Negative and positive peer influence: Relations to positive and negative behaviors for African American, European American, and Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2009;32(2):323–337. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsai M, Voisine S, Marsiglia FF, Kulis S, Nieri T. The protective and risk effects of parents and peers on substance use, attitudes, and behaviors of Mexican and Mexican American female and male adolescents. Youth & Society. 2008;40(3):353–376. doi: 10.1177/0044118x08318117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedlow CT, Carey MP. Developmentally appropriate sexual risk reduction interventions for adolescents: Rationale, review of interventions, and recommendations for research and practice. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:172–184. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2703_5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez FV. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Texas A&M University; College Station, TX: 2011. The impact of traditional gender role beliefs and relationship status on depression in Mexican American women: A study in self-discrepancies. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Stages of ethnic identity in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1989;2:34–49. doi: 10.1177/0272431689091004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;7:156–176. doi: 10.1177/074355489272003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS. Understanding ethnic diversity: The role of ethnic identity. American Behavioral Scientist. 1996;40:143–152. doi: 10.1177/0002764296040002005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Ong AD. Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54(3):271–281. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, Ong A, Madden T. Cultural values and intergenerational value discrepancies in immigrant and non‐immigrant families. Child development. 2000;71(2):528–539. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priess HA, Lindberg SM, Hyde JS. Adolescent gender‐role identity and mental health: Gender intensification revisited. Child development. 2009;80(5):1531–1544. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, Ontai LL. Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles. 2004;50(5–6):287–299. doi: 10.1023/b:sers.0000018886.58945.06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Hughes D, Way N. A preliminary analysis of associations among ethnic-racial socialization, ethnic discrimination, and ethnic identity among diverse urban sixth graders. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2009;19:558–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00607.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, Romero A. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. The Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:301–322. doi: 10.1177/0272431699019003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers CR, Nichols TR, Botvin GJ. Alcohol and cigarette free: Examining social influences on substance use abstinence among Black non-Latina and Latina urban adolescent girls. Journal of Child & Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2011;20(4):370–386. doi: 10.1080/1067828x.2011.599274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez KM, Castillo LG, Gandara L. The influence of marianismo, ganas, and academic motivation on Latina adolescents’ academic achievement intentions. Journal of Latina/o Psychology. 2013;1(4):218–226. doi: 10.1037/lat0000008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saluja G, Iachan R, Scheidt PC, Overpeck MD, Sun W, Giedd JN. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158(8):760. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez D, Whittaker T, Hamilton E, Arango S. Familial ethnic socialization, ethnic identity development, and mental health in Mexican-origin early adolescents. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2017;23:335–347. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000142. [Advanced online publication] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez D, Whittaker T, Hamilton E, Zayas L. Perceived discrimination and sexual precursor behaviors in Mexican American preadolescent girls: the role of psychological distress, sexual attitudes and marianismo beliefs. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2015;22:395–407. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Jarvis LH. Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2007;13:364–373. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott SM, Wallander JL, Depaoli S, Elliott MN, Grunbaum J, Tortolero SR, Schuster MA. Gender role orientation is associated with health-related quality of life differently among African-American, Hispanic, and White youth. Quality of Life Research. 2015;24:2139–2149. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-0951-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields SA. Gender: An intersectionality perspective. Sex Roles. 2008;59:301–311. doi: 10.1007/s11199-008-9501-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stueve A, O’Donnell L. Early alcohol initiation and subsequent sexual and alcohol risk behaviors among urban youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95:887–893. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.026567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: Mental health findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. Substance Abuse, and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] (NSDUH Series H-49, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4887). [Google Scholar]

- Supple AJ, Ghazarian SR, Frabutt JM, Plunkett SW, Sands T. Contextual influences on Latino adolescent ethnic identity and academic outcomes. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1427–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00945.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ. Ethnic identity and self-esteem: Examining the role of social context. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27:139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Guimond AB. A longitudinal examination of parenting behaviors and perceived discrimination predicting Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity. Journal of Latina/o Psychology. 2012;1(S):14–35. doi: 10.1037/a0019376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umana-Taylor AJ, Guimond AB. A longitudinal examination of parenting behaviors and perceived discrimination predicting Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity. Developmental Psychology. 2012;46(3):636–650. doi: 10.1037/a0019376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, Study Group on Ethnic and Racial Identity Ethnic and racial identity revisited: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development. 2014;85:21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Vargas-Chanes D, Garcia CD, Gonzales-Backen M. A longitudinal examination of Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity, coping with discrimination, and self-esteem. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2008;28:16–50. doi: 10.1177/0272431607308666. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Unger JB, Ritt-Olson A, Soto DW, Baezconde-Garbanati L. Parent–child acculturation discrepancies as a risk factor for substance use among Hispanic adolescents in Southern California. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health. 2009;11:149–157. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9083-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upchurch DM, Aneshensel CS, Mudgal J, McNeely CA. Sociocultural contexts of time to first sex among Hispanic adolescents. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;63(4):1158–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.01158.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health, and Human Services (DHHS) Results from the 2010 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Williams LS, Alvarez SD, Andrade Hauck KS. My name is not Maria: Young Latinas seeking home in the heartland. Social Problems. 2002;49:563–584. doi: 10.1525/sp.2002.49.4.563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RJ, Chang SY. A comprehensive and comparative review of adolescent substance abuse treatment outcome. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2000;7(2):138–166. doi: 10.1093/clipsy.7.2.138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williford A. Assessing a measure of femininity ideology for low-income, Latina adolescent girls. Journal of Women and Social Work. 2011;26(4):395–405. doi: 10.1177/0886109911428589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zamboanga BL, Schwartz SJ, Jarvis LH, Van Tyne K. Acculturation and substance use among Hispanic early adolescents: Investigating the mediating roles of acculturative stress and self-esteem. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2009;30:315–333. doi: 10.1007/s10935-009-0182-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas L, Lester R, Cabassa L, Fortuna L. Why do so many Latina teens attempt suicide? A conceptual model for research. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:275–287. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Pilat AM. Suicidal behavior in Latinas: Explanatory cultural factors and implications for intervention. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38(3):334–332. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.3.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]