Abstract

The objective of this study was to develop an injectable and biocompatible hydrogel that can deliver a cocktail of therapeutic biomolecules (secretome) secreted by human adipose-derived stem cells (hASCs) to the peri-infarct myocardium. Gelatin and Laponite® were combined to formulate a shear-thinning, nanocomposite hydrogel (nSi Gel) as an injectable carrier of secretome (nSi Gel+). The growth factor composition and the pro-angiogenic activity of the secretome were tested in vitro by evaluating the proliferation, migration and tube formation of human umbilical endothelial cells. The therapeutic efficacy of the nSi Gel+ system was then investigated in vivo in rats by intramyocardial injection into the peri-infarct region. Subsequently, the inflammatory response, angiogenesis, scar formation, and heart function were assessed. Biocompatibility of the developed nSi Gel was confirmed by quantitative PCR and immunohistochemical tests which showed no significant differences in the level of inflammatory genes, microRNAs, and cell marker expression compared to the untreated control group. In addition, the only group that showed a significant increase in capillary density, reduction in scar area and improved cardiac function was treated with the nSi Gel+. Our in vitro and in vivo findings demonstrate the potential of this new secretome-loaded hydrogel as an alternative strategy to treat myocardial infarction.

Keywords: Shear thinning hydrogels, nanocomposite hydrogel, myocardial therapy, secretome

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

On average, one person dies of cardiovascular disease (CVD) every 40 seconds in the United States [1] making CVD the leading cause of death in this country. [2] Specifically, ischemic heart disease (IHD), characterized by myocardium necrosis initiated by a lack of oxygen supply to the left ventricle, has a higher mortality rate worldwide than any other CVD. [3] Although many patients survive the myocardial infarction (MI) caused by IHD, the absence of robust intrinsic regenerative responses in the heart ultimately leads to heart failure due to the replacement of functional myocardium with fibrotic scar tissue.

To overcome this adverse remodeling of the myocardium and restore proper heart function, scientists have aimed to promote myocardial regeneration using adult mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). Promising results have been reported in preclinical and early phase clinical trials using MSCs which demonstrated their therapeutic ability by promoting cardioprotection, endogenous cardiac stem cell stimulation, angiogenesis, and antifibrosis. [4] However, recent evidence indicates that several of these positive outcomes are likely not due to the transdifferentiation and engraftment of the MSCs at the therapeutic site but mainly because of the release of paracrine factors (cytokines, growth factors, and exosomes) from the cells. [5–7] This mixture of bioactive molecules known as secretome can be isolated in vitro, and the biomolecule composition has been shown to greatly depend on the culture conditions that the stem cells are subjected to. Scientists have proven that several parameters such as oxygen percentage, serum concentration, and degree of cell-cell interactions can cause diverse biomolecule secretion profiles. [8, 9] Therefore, significant efforts have been dedicated to characterizing and optimizing the regenerative potential of stem cell-derived secretome, which has several advantages over traditional stem cell therapy. These include the lack of immunogenic rejection allowing for an off-the-shelf product, minimized concern of an oncogenic response, and the possible control over the protein milieu contents through the use of multiple in vitro techniques. [10] However, much like traditional stem cell therapy, a simple injection of secretome in the peri-infarct area without any additional carriers often results in a lack of retention at the delivery site. In fact, therapies based on the bolus injection of multiple growth factors are generally associated with an insufficient local regenerative response along with undesirable off-target effects. [11] Therefore, a method that provides a prolonged retention of secretome at the injection site represents an essential requirement to observe optimal therapeutic efficacy. [12–15]

Injectable hydrogels developed from synthetic and natural biomaterials can potentially provide a method to achieve this goal. [16] Various physical and chemical crosslinking mechanisms can be used to develop hydrogel networks that respond to different stimuli including mechanical stress, pH, enzyme, ionic strength, and temperature variation. [17] Additionally, the introduction of a nanomaterial within the network can modulate their physical properties causing them to exhibit thixotropic behavior. [18] For instance, the formation of nanocomposite hydrogels through the incorporation of various carbon-based, polymeric, and inorganic nanomaterials within the polymeric network has emerged as a valuable method to achieve this desired behavior. [19–23] Among them, synthetic nanoclay, specifically Laponite® ((Na0.7+ [(Si8Mg5.5Li0.3)O20(OH)4]0.7−), represents an ideal choice for regenerative medicine applications. Laponite® is a smectite nanoclay comprised of disk-shaped nanoparticles with a diameter of approximately 25 nm and a 1 nm thickness. These nanoparticles overcome biocompatibility concerns associated with some carbon-based nanoparticles while maintaining superior growth factor loading capabilities due to their high surface-to-volume ratio and discotic charged surface. [24, 25] In addition, Laponite® can modulate the release of biomolecules loaded in the hydrogel through electrostatic interactions allowing the use of this type of hydrogel in regenerative tissue applications. [25] Following this strategy, recent studies have demonstrated how the presence of this nanosilicate can help control the release of growth factors at the site of administration and promote significantly more tissue regeneration than corresponding bolus injections of proteins. [26–28]

Previously, we have used these nanocomposite hydrogel characteristics to our advantage for the controlled delivery of stem cell derived secretome in vitro. [25] We demonstrated that a photocrosslinkable, methacrylated gelatin based nanocomposite scaffold containing Laponite® can control the release of key therapeutic growth factors present in bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell secretome over a prolonged period of time. In addition, in vitro cell based assays showed that the secretome loaded nanocomposite hydrogel has both proangiogenic and cardioprotective ability. Building on these encouraging results and recent literature highlighting the proangiogenic potential of hASC-derived secretome in comparison to secretome from bone marrow and Wharton’s jelly derived stem cells, we aimed to develop an injectable nanocomposite hydrogel for the delivery of hASCderived secretome to promote myocardial regeneration post myocardial infarction. [29] We hypothesized that the secretome loaded nanocomposite hydrogel would efficiently promote key therapeutic mechanisms including angiogenesis, scar area reduction, and cardioprotection. Through this strategy, we sought to improve cardiac function and demonstrate the potential of stem cell-derived secretome as an alternative to traditional stem cell therapy for myocardial regeneration.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Preparation and physical characterization of the nanocomposite hydrogels

Synthetic silicate nanoplatelets (Laponite® XLG) containing SiO2 (59.5%), MgO (27.5%), Na2O (2.8%), Li2O (0.8%) and a low content of heavy metals were supplied by Southern Clay Products, Inc. (Louisville). Gelatin type A from porcine skin bloom grade 300 was used without further modification from the manufacturer (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

A stock solution of 10% w/v gelatin was prepared by dissolving the protein in PBS (pH=7.4) at 37 °C. Stock suspensions of 1, 2, 3, and 4% w/v Laponite® were prepared in ultrapure water at room temperature. The nanocomposite hydrogels were formed by mixing equivalent volumes of the gelatin stock and the corresponding nanoplatelet suspensions in order to obtain a final concentration of 5% w/v gelatin and 0.5, 1, 1.5, and 2% w/v nanosilicates. The hydrogels were used immediately after their preparation unless otherwise specified. Hydrogels were also frozen and freeze dried prior further characterization using elementary Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR). To carry out SEM and EDX characterization, freeze dried samples were mounted on a holder with double sided conductive carbon tape and sputter-coated with gold. SEM images were obtained at an acceleration voltage ranging from 1 to 10 kV with an in-lens detector. For FT-IR spectra analysis, the gels were mixed in KBr tablet, and spectra were recorded in the range of 400 to 4000 cm−1 (resolution of 1 cm−1) using a Bruker Vector-22 FTIR spectrophotometer (PIKE Technologies, USA). [30]

Degradation studies were carried out to assess the stability of the nanocomposite hydrogels containing either 0, 1, or 2% (w/v) Laponite®. Each nanocomposite hydrogel was initially freeze dried and weighed prior to the study which was performed in PBS (pH 7.4) at 37 °C while shaking the gel at 60 rpm for 2 weeks. The PBS was replaced every two days. At various time points five samples of each Laponite® concentration were freeze dried and weighed to calculate the percentage of degradation indicated by weight loss using the following equation (1):

Wi and Wf are the initial and final weight of the nanocomposite hydrogel after degradation, respectively.

Finally, myoglobin was used to determine whether the Laponite® concentration within the nanocomposite hydrogel effected the release profile of a loaded protein.

Nanocomposite hydrogels containing either 1 or 2% Laponite® were loaded with 5 mg/mL myoglobin and subjected to shaking of 60 rpm at 37 °C in the presence of PBS. The concentration of myoglobin within the PBS was determined at various time points by measuring the absorbance at 410 nm.

2.2 Harnessing the hASCs secretome using a microchip device

StemFIT 3D microwell® culture dishes were used to culture hASCs spheroids. Each culture dish was 300 mm in diameter containing 389 wells with a diameter of 600 µm. The hASCs used were purchased from Rooster Bio and originated from female donors between the ages of 31–45 years old. Flow cytometry was used by the company to determine that less than 20% of the cells expressed CD14, CD34, CD45 and greater than 70% of the cells expressed CD166, CD105, CD 90, and CD73. In addition to a phenotype confirmation, the multipotency of the cells was tested using 3 week cell differentiation studies. Positive Oil Red O and Alizarin Red staining confirmed the adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation abilities of the cells. These polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) concave microwells were purchased from Prodizen (Seoul, Korea) and used according to the manufacture’s protocol. hASCs (passage 2–6) were initially cultured in traditional 2D conditions (3.3 × 103 cells/cm2) using hASC High Performance Media (Rooster Bio). The hASCs were then trypsinized and resuspended in serum-free α-MEM media supplemented with 1% L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. hASCs were seeded in the microchips at a cell density of 0.8 × 106 cells per mL. The cells were allowed to settle into the microwells of the microchips for 20 minutes prior to removing all the media being cautious not to withdraw any of the cells in the microwells. This step is necessary to remove all the cells on the periphery of the wells and ensure optimal spheroid formation in the microwells. Finally, 1 mL of serum-free α-MEM media supplemented with 1% of L-glutamine and 1% penicillin/streptomycin was added to each microchip. The hASCs were incubated for 72 hours at 37° C to allow spheroid formation and the secretion of paracrine factors into the media (secretome). The resulting spheroids were fluorescently stained with ethidium bromide (0.2% v/v) and calcein (0.05% v/v) dye to visualize dead and living cells, respectively and assess whether the culture conditions caused any significant cell death. After 72 hours the secretome was collected from the chips, centrifuged at 1000 RPM for 5 minutes, and the secretome supernatant was collected to ensure there was no cellular debris in the secretome. A human angiogenesis antibody array and cytokine array (R&D Systems) were used to detect the relative levels of 55 angiogenic-related proteins and 36 different cytokines, chemokines and acute phase proteins in the secretome. More specifically, images were taken of each chemiluminescent blot, and the mean spot pixel densities for each protein were calculated using ImageJ software. To quantify specific angiogenic growth factors such as VEGF and Angiogenin, their respective ELISA kits were used according to the manufacture’s protocols (R&D Systems and System Biosciences).

2.3 Rheological Analysis

An AR2000 rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE) was used for mechanical characterization of the nanocomposite hydrogels containing varying concentrations of Laponite®. Viscosity measurements were performed immediately after the Laponite® was homogeneously distributed into the gelatin polymeric solution. The test was carried out using a cone-plate geometry (cone with 20 mm diameter, 1° angle) in the range of shear rates varying from 0.001 to 1000 s−1. The study was conducted at the temperature of 25 °C (n=3). To study the hydrogel mechanical properties, cylindrical hydrogels were formed by introducing 0.5 mL of the gelatin-silicate mixture into in a 24 well plate and allowed to gel overnight at 4 °C. Prior to testing, all gels were removed and allowed to reach 20°C. All tests were performed at 25 °C using a roughened plate geometry (20 mm diameter). An initial strain sweep from 0.1% to 100% at 1 Hz was performed to determine the linear viscoelastic region of the hydrogel that was used for subsequent frequency sweep tests carried out in the range from 0.01 to 10 Hz (n=3). Recovery testing was conducted at 1 Hz by subjecting the hydrogels to 3 consecutive cycles of 5 minutes at 1% strain (within the linear viscoelastic region) and 5 minutes at 100% strain (outside the linear viscoelastic region) (n=3). Temperature sweeps from 25 °C to 40 °C were conducted at 1 Hz and 1% strain (n=3)

2.4 Biocompatibility of the Nanocomposite Hydrogel in vitro

Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (8 × 104) were seeded in chamber slides with 10% of the media volume replaced with the gelatin-silicate mixture deriving from each of the different test groups (Lap 0, 1, and 2% w/v). The positive control group (Cntrl+) contained only media. As a negative control (Cntrl−), camptothecin at a concentration of 50 µM was added to the media. After 24 hours, cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 5 minutes at 37 °C. Diamidino-2-phenylindole dilactate (DAPI, Invitrogen, USA) and phalloidin-AlexaFluor488 (Invitrogen, USA) were used to counterstain nuclei and actin, respectively. Immunofluorescence images were taken to observe whether or not the addition of the hydrogel had any effect on cell morphology.

Additionally, HUVECs were seeded in a 24 well plate and allowed to reach confluency in endothelial growth medium (EGM-2 BulletKit Lonza, Waldersville, MD) at 37°C and 5% of CO2. Subsequently, to assess the cytotoxicity of the nanocomposite hydrogel, a Falcon® Permeable Support (3.0 µm transparent PET membrane) containing 200 µL of the respective nanocomposite hydrogel from each of the different test groups (Lap 0, 1, and 2% w/v) was added to each well. As a control group, HUVECs were not treated with any gels. After 1 day, 3 days, and 5 days of gel exposure, cells were washed with fresh media and an MTS assay was carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions. [31] The absorbance of each well was measured at 490 nm to determine the HUVECs’ mitochondrial activity (Cell Titer 96 Aqueous Non-Radioactive Assay, Promega). The number of cells was determined using a calibration curve in the range from 5 × 103 up to 2 × 105 cells.

2.5 HUVEC proliferation, migration and tube formation assays

To assess the proangiogenic ability of the secretome, HUVECs (1 × 104 cells/well) were seeded in a 48 well plate and allowed to grow in the media (200 µL) without the addition of VEGF and human fibroblast growth factor-B (hFGF-B). After 3 hours, one-fourth of endothelial growth medium (50 µL) was replaced by secretome derived from the 2D monoculture (2D secretome) or the spheroids (3D secretome) providing a VEGF concentration of 0.15 ng/mL and 1.2 ng/mL, respectively. This volume of secretome was determined to be the optimal volume of α-MEM media tolerated by the HUVECs to allow for the observation of the proangiogenic ability of each type of secretome. As a negative control, cells were not supplemented with any growth factor in the media (Cntrl (−)). The degree of HUVEC proliferation in the presence of the secretome was assessed by MTS cell proliferation assay (n=5) after 24 hours as described in the previous section.

Additionally, HUVECs were also cultured in a 24 well plate (2 × 104 cells/well) and allowed to become confluent in endothelial growth medium (400 µL) without the addition of VEGF and hFGF-B. Then, scratches were made in the cell monolayer using a cell scraper followed by several washes with PBS to remove the detached cells. 2D secretome and 3D secretome were supplemented in the media (100 µL), and HUVECs were allowed to migrate through the scratch for 24 hours. Cells were stained with calcein, and fluorescent images were taken in the same positions along the scratch before and after the 24 hour migration period in all the groups. The cells that did not receive any growth factor supplement served as the negative control. The percentage of area recovered during the migration was calculated using Image J software. The original wound area was determined from the preliminary images and the area recovered was defined as the total wound area that was occupied by cells post 24-hour incubation. [19]

Finally, to determine the secretome’s ability to induce the formation of tubular-like structures, HUVECs were seeded on a growth factor depleted Matrigel-based on the manufacturer’s protocol (Matrigel matrix, Basement Membrane, BD). Briefly, 289 µL of growth factor depleted Matrigel Matrix (10 mg/mL) previously cooled to approximately 5 °C was added to a 24 well culture plate on ice. The plate was then incubated at 37°C for 60 minutes to allow the gel to form. Then, HUVECs (1.2×105) were seeded on each gel with either endothelial growth medium without growth factors (Cntrl (−)) or supplemented with 2D and 3D secretome. After 10 hours, bright field images of the endothelial networks were taken for each group and the number of complete tubes formed, total network length and total segment length were determined using the Angiogenesis Analyzer for ImageJ. The average numbers from three independent wells were reported. [32]

2.6 qPCR analysis of apoptotic and stress-related genes in spheroids

RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Germany) was used to extract mRNA from the hASCs spheroids and hASCs cultured in well plates following the manufacturer’s protocol. The total RNA concentration and purity were determined by measuring the optical density at 260 nm using a spectrophotometer (Nanodrop ND-1000; Thermo Scientific, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized starting from the isolated RNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystem, USA). The qPCR analysis was performed in triplicate for each test group on a Mastercycler Realplex (Eppendorf, Germany) using predesigned primers and KiCqStart SYBR Green qPCR Ready Mix (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Fold expression levels of BCL-2, EPAS1 and HIF1A were calculated using the relative ••Ct method,, using GAPDH as the housekeeping gene. The gene expression of the hASCs grown in traditional 2D tissue culture flasks was used as a reference group.

2.7 Biocompatibility assessment of nanocomposite hydrogel in vivo

In vivo biocompatibility experiments were performed using male adult Fischer 344 rats (~8 weeks), each weighing 250–300 g. [19] Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane gas followed by tracheal intubation and ventilation using Rodent Ventilator (Minivent, Type 845 Germany). Animal body temperature was maintained at 37°C during the surgery. Nanocomposite hydrogels were formulated in accordance with the procedure used for the in vitro studies. The hearts were exposed by minimal left-sided thoracotomy and 100 µl of nanocomposite hydrogel (nSi Gel) [5.0% (w/v) Gelatin, 2.0% (w/v) Silicate] or PBS (Control) was intramyocardially injected at multiple sites (5 sites/heart). A total of 10 rats were used (n=5). The chest was closed, and animals were allowed to recover. The animals were maintained on buprinex after surgery for 24 h.

For immunostaining paraffin embedded heart sections were deparaffinized by Xylene to 100% ethanol change (5 min each) and antigen retrieval was done using citrate buffer according to standard protocols. Heart sections were blocked by CAS-block Histochemical Reagent (Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA) for 2 hours at room temperature followed by three PBS washes for 5 minute each. Primary antibodies for TnC (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and TNFα (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were used in a working dilution of 1:200 with CAS-Block and individually incubated for overnight at 4°C followed by three PBS washes for 5 minute each. The corresponding secondary antibodies were used in a working dilution of 1:200 with CAS-Block and individually incubated for 2 hours at room temperature followed by three 5 minute PBS washes. Nuclei were stained by DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Images were analyzed using fluorescent microscopy. In addition to immunostaining, A TUNEL assay was performed on deparaffinized 5 µm thick sections with an In-Situ Cell Death Detection Kit, TMR Red (Roche Inc) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. [33] Nuclei were stained by 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). The degree of apoptotic cell death was evaluated by calculating the ratio of TUNEL-positive cells to the total number of cells.

Lastly a qPCR analysis of cardiac function and cardiomyocyte cell cycle genes was performed on the myocardium. The frozen tissue samples were homogenized by The Bullet Blender homogenizer (Next Advance, Inc, USA) followed by the total RNA isolation by using Ambion™ TRIzol™ Reagent (Fisher Scientific, USA). Quantification of RNA was done by NanoVue™ Plus Spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) and RNA quality was checked on 1.0% agarose gel. cDNA synthesis was performed with 1µg total RNA of each sample by using Omniscript Reverse Transcription kit (QIAGEN, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RT-PCR expression analysis for APC, TNFα, CyclinD1, Rb1, and Meis2 was performed using specific RT-PCR primer pairs for each gene (Fig S8C). RT-PCR primers were synthesized by using Primer3web version 4.0.0 (http://bioinfo.ut.ee/primer3/), and primer quality was checked by UCSC In-Silico PCR (http://rohsdb.cmb.usc.edu/GBshape/cgi-bin/hgPcr). Amplification reactions were performed in duplicate in CFX Connect™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, California, USA) using Applied Biosystems® SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA) following the manufacturer’s amplification conditions. Quantification of RT-PCR data was performed by using the ΔΔCt method and β-actin served as control. [33] For the miRNA qPCR, total RNA was isolated by Trizol method, as previously described. The miRNA cDNA synthesis was performed using the miScript II RT Kit dual-buffer system (Qiagen) and miScript HiSpec Buffer. The subsequent miRNA quantification was performed by using miScript Primer Assays according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Specific forward primers (Figure S8C) with a universal reverse primer were used for the RT-PCR reaction. (http://sabiosciences.com/manuals/BRO_GEF_miRNA_0212_lr.pdf). RT-PCR reactions were performed according to the standard manufacturer’s protocol. RNU6 served as internal control. The quantification of miRNA expression was performed using the ΔΔCt method previously described.

2.8 In vivo acute myocardial infarction surgery

According to established protocols and in compliance with NIH Guide care and Use of Laboratory animals, in vivo experiments were performed using a myocardial infarction rat model with adult (~8 weeks) male Fischer 344 rats, each weighing 250–300 g. [19] Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane gas followed by tracheal intubation and ventilation using Rodent Ventilator (Minivent, Type 845 Germany). Animal body temperature was maintained at 37°C during the surgery. Nanocomposite hydrogels were formulated in accordance with the procedure used for the in vitro studies. The hearts were exposed by minimal left-sided thoracotomy and an occlusion of the left ascending coronary artery was used to induce an acute MI according to conventional laboratory procedures. [34–36] Lyophilized 3D secretome was resuspended in PBS (0.125 mL) and mixed with Gelatin 20% w/v (0.125 mL) and Laponite 4% (0.25 mL) to obtain nSi Gel+. The nSi Gel was formulated using PBS in place of secretome. Then, 15 minutes post infarction 100 µL of either the nanocomposite hydrogel (nSi Gel) or the 3D secretome loaded nanocomposite hydrogel (nSi Gel+, 8 ng VEGF/ rat, 5 ng ANG/rat) was injected in five different sites within the peri-infarct region of the heart using a 28 gauge syringe (20 µL/injection) (n=5). The control group received an injection of PBS 15 minutes post infarction (n=5). As an additional control group, a secretome was also included and was injected with a secretome solution containing the same amount of VEGF and ANG in the nSi Gel+ 15 minutes post infarction (n=5). A total of 20 rats were used (n=5). The chest was closed, and animals were allowed to recover. The animals were maintained on buprinex after surgery for 24 h. For the heart function assessments, transthoracic echocardiography was performed at day 0, 3, 7, 14, and 21 after surgery for therapeutic efficacy studies. After day 21, the animals were sacrificed, and hearts were frozen or fixed with 4% formalin solution for molecular and histological studies.

2.9 In vivo assessment of cardiac function

Cardiac function was assessed by transthoracic echocardiography 0, 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after surgery using Vevo®2100 Imaging System, Visualsonics with a 24-MHz transducer, MS250 followed an established protocol. [37, 38] Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane gas, 2-D imaging of hearts was performed and recorded for M-modes through the anterior and posterior left ventricle (LV) walls. Anterior and posterior wall thickness (end-diastolic and end-systolic), LV internal dimensions, LV end-systolic (LVESd) and end-diastolic (LVEDd) diameters were measured from at least 3 consecutive cardiac cycles. Indices of LV systolic function including left ventricle ejection fraction (EF), left ventricle fractional shortening (FS) and cardiac output (CO) were calculated as follows:

Cardiac output = heart rate × stroke volume. The results were expressed as percentage ± standard deviation.

2.10 Immunostaining of heart sections

Paraffin-embedded heart sections were deparaffinized by introducing the slides in xylene followed by a wash with 100% ethanol. Both steps were carried out for five minutes. Antigen retrieval was done using a standard citrate buffer protocol. [38] Heart sections were blocked by CAS-block Histochemical Reagent (Thermo Fischer Scientific, USA) for 2 hours at room temperature followed by three PBS washing with 5 minutes interval between each wash. Primary antibodies for von Willebrand Factor (vWF) (catalog # A0082, Dako, Agilent Pathology Solutions, USA) and smooth muscle actin (SMA) (catalog # A2547 SIGMA, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were used at a working dilution of 1:200 with CAS-Block. Both antibodies were individually incubated overnight at 4°C followed by three PBS washing with 5 minutes interval within each wash. The corresponding secondary antibodies were used at a working dilution of 1:200 with CAS-Block and individually incubated for 2 hours at room temperature followed by three PBS washing with 5 minutes interval within each wash. The nuclei were stained using DAPI (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Images were analyzed using fluorescent microscopy. The results were compared by student’s t-test and a p value ≤ 0.05 was considered as significant. Results were represented as mean ± standard deviation.

2.11 Statistics

All quantitative data are presented as mean ± standard deviation from individual experiments. A two-way or one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by Tukey’s multiple comparison posthoc test was performed to assess statistical significance with a p-value of <0.05 considered significant. Prism 5 (GraphPad Software) was used to carry out all statistical analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1 Secretome Preparation and Characterization

Several different in vitro cell culture techniques have been used to modulate the concentration and composition of growth factors and cytokines present in the secretome to promote specific regenerative responses. [9] Here we used polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microwell culture devices to form hASCs spheroids for secretome production. The green fluorescent images of the spheroids showed that the spheroids were largely composed of living hASCs with a minimal presence of dead cells in each spheroid (Fig 1A). This technique was chosen based on the generally accepted idea that spheroid culture techniques promote a cellular environment more representative of an in vivo setting than traditional 2D monolayer culture. This assumption is based on the greater amount of cell to cell interactions and cellular interfaces with extracellular matrix components which occur within spheroids. [39] In addition, the spheroid structure relies on diffusion to control the transport of nutrients, oxygen, and waste throughout the entirety of the sphere. This diffusion limitation provokes a state of stress within the cells which has been shown to alter the growth factor secretion. [40, 41] Lastly, the high ratio of cells to media used allows for the collection of a highly concentrated secretome. [25]

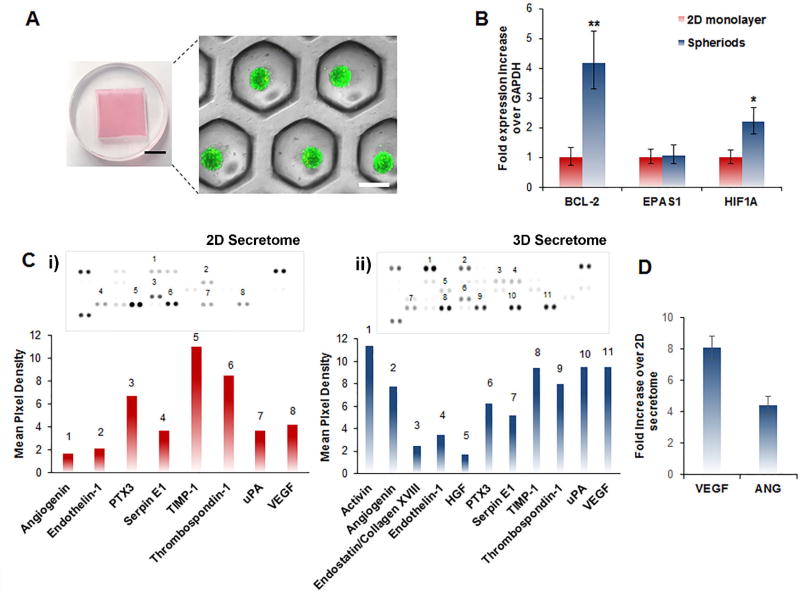

Figure 1.

Preparation and characterization of secretome isolated from both hASC spheroids (3D secretome) and hASC monolayer (2D secretome). A) Microwell culture dish used for hASCs spheroid culture and characteristic fluorescent microscopy image of resultant spheroids superimposed on an equivalent bright-field image. Calcein and ethidium bromide was used to visualize live and dead cells, respectively. (Black scale bar: 1 mm, white scale bar: 200 µm). B) Gene expression analysis of hASCs culture in a traditional monolayer and in spheroids using qPCR. The data in the graph represents fold changes in the expression levels of anti-apoptotic and stress related genes between the two groups. Data are expressed as mean value ± standard deviation * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, (n = 3). C) i) Human angiogenic dot blot array of 2D hASCs monolayer derived secretome and corresponding quantification of the mean pixel density quantified using ImageJ software. ii) Human angiogenic dot blot array of hASCs spheroid-derived secretome, and the corresponding quantification of the mean pixel density quantified using ImageJ software. The presence of key cardioprotective and angiogenic factors such as endostatin/collagen XVIII and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) were only detected in the secretome derived from hASCs spheroid. D) ELISA quantification of the concentration of VEGF and angiogenin (ANG), present in the secretome. The data are represented as the fold increase in growth factor concentration in the secretome derived from hASCs spheroids with respect to the secretome isolated from the monolayer hASCs culture. Data are expressed as mean value ± standard deviation (n=3).

After 72 hours of culture, the hASCs spheroids showed an increased expression of the anti-apoptotic gene BCL-2 as well as, the stress related gene HIF1A when compared to traditional 2D monolayer culture (Figure 1B). The increased gene expression has been previously reported to occur within spheroids and has been shown to be linked to hypoxia and hypoxia-dependent pathways. [42] In addition to the difference in gene expression between the two culture techniques, a human antibody array was carried out to evaluate the composition of therapeutic growth factors, cytokines, and proteins present in the secretome (Figure 1C and 1D). The protein endostatin/collagen XVIII and the hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) were only detected in the spheroid secretome (Figure 1D). Recently, endostatin/collagen XVIII has been linked to the suppression of type I collagen expression in cardiac fibroblasts which is a vital component of scar formation post myocardial infarction. [43] Additionally, the inhibition of endostatin/collagen XVIII in a rat MI model was shown to cause an increase in matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) activity of MMP2 and MMP9, angiotensin converting enzyme activity, and collagen deposition. [44] These findings suggest that endostatin/collagen XVIII may have a significant cardioprotective ability and a precise role in limiting myocardium remodeling. The second component that was exclusively detected in the spheroid secretome, HGF, is an effective agonist for the tyrosine kinase surface receptor c-MET. [45] This cytokine has been documented to exhibit pro-angiogenic, anti-fibrotic, and cardioprotective ability in vitro and in vivo MI models. [46–49] Along with the previously discussed therapeutic biomolecules only being secreted by the spheroids, there were also several growth factors present at a greater concentration in the spheroid secretome when compared to the 2D monolayer secretome. Specifically, the concentration of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and angiogenin was approximately eight and four times greater in the spheroid secretome, respectively (Figure 1E). These proteins are potent proangiogenic growth factors with a proven ability to promote endothelial proliferation, migration, and survival as well as, facilitate new blood vessel formation within the peri-infarct zone post-MI. [50–53] These results confirm that culturing hASCs in spheroids rather than a monolayer changes the genetic profile of the cells and subsequently provokes the cells to secrete a greater amount and variety of therapeutic molecules involved in angiogenesis, cardioprotection, and improvement of the heart function post-MI.

3.2. In vitro Proangiogenic Activity of Secretome

As mentioned previously, MI is initiated by the obstruction of blood flow to the myocardium as the result of an occlusion of the coronary arteries leading to the walls of the heart. The resulting ischemia causes several pathological changes within the myocardium such as hypoxia, inflammation, ventricular dilation, compromised contractile function, cardiomyocyte death, and tissue necrosis. [54, 55] Therefore, regardless of the method used, in order to repair the infarcted myocardium the reestablishment of sufficient vascularization throughout the heart is essential to ensure proper metabolic and structural homeostasis of the myocardium. [56] Therapeutic angiogenesis is an essential process involved in the revascularization, and consequently, the angiogenic potential of the hASCs derived secretome was characterized using several in vitro cell based assays.

Initially, angiogenesis relies on endothelial cell migration and proliferation to form capillary sprouts [57]. To assess cell proliferation, endothelial cells were seeded at a sub-confluent density in growth factor depleted endothelial growth media. Then, the two different hASCs derived secretome isolated respectively from 2D monoculture (2D secretome) and spheroids (3D secretome) were added to the media in different groups, and the cell number was quantified after 24 hours.

As a control group (Cntrl (−)), cells were grown in endothelial growth media without the addition of VEGF and human fibroblast growth factor-B (hFGF-B). The 3D secretome caused a significant increase in cell proliferation when compared to 2D secretome (Fig 2A). Next, an in vitro scratch assay was performed to assess whether the secretome was able to promote endothelial cell migration.

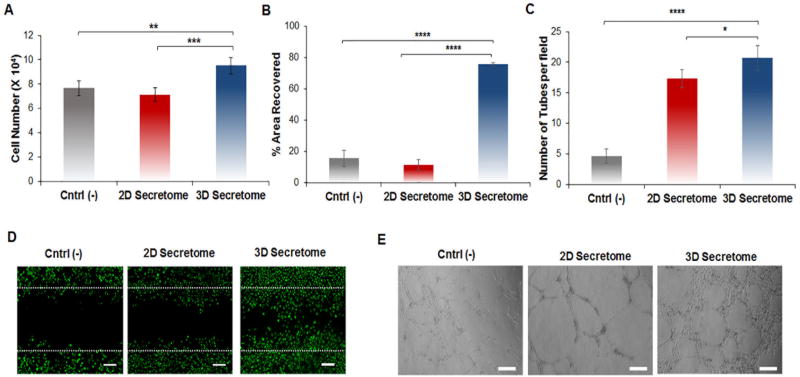

Figure 2.

In vitro superior angiogenic potential of hASCs spheroid-derived secretome. A) The proliferation of HUVECs was carried out in endothelial growth medium without VEGF and hFGF-B. Cells were treated with hASCs monolayer derived secretome (2D secretome), and hASCs spheroid-derived secretome (3D secretome) for 24 hours. As control group (Cntrl (−)), cells were cultured without growth factors. HUVECs number was determined using an MTS assay. Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (n=5). B) Quantification of the % of area covered by HUVECs after 16 hours in the different groups. The analysis was carried out by quantifying the area occupied by the HUVECs within the wound area post 16hour incubation using ImageJ software. C) Quantification of complete tube formation after 24 hours in the different groups. Data are expressed as mean of tubes formed in each group ± standard deviation (n=3). * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, **** p<0.001. D) Fluorescent images of HUVECs stained with calcein showing their migration within the scratch area in the different groups after 16 hours. Scale bar: 100 µm. Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (n=3). E) Representative bright-field images of a Matrigel tube formation assay for the different groups after 10 hours. Scale bar: 200 µm.

After 16 hours of treatment, differences in cell migration could be observed within the scratch that was made prior to the addition of secretome. Specifically, treatment with the 3D secretome resulted in a 75.7% wound closure which was significantly higher than the 2D secretome group (Fig 2B and 2D). These results align with previous reports of endothelial migration induced by angiogenic protein-based treatments. [21, 58] Lastly, a tube formation assay was carried out. This assay is essential because, following the formation of capillary sprouts via endothelial cell migration and proliferation, cellular alignment into tubules is essential for lumen formation of a functional capillary. [59] After 10 hours of exposure to the secretome, the test groups containing the 2D secretome as well as the 3D secretome showed an increase in tube formation. The groups that received the 2D and 3D secretome showed approximately four and five times more tubes per field when compared to the control, respectively (Fig 2C and 2E). In addition, the 2D and 3D secretome induced the formation of longer tube segments and a larger total tube length (Fig S4). Based on the results obtained from these three cell-based assays, the prediction that the secretome composition derived from hASCs spheroids has superior proangiogenic properties when compared to the secretome isolated from the hASCs cultured in a traditional monolayer can be confirmed. [60]

3.3 Formation and characterization of the injectable nanocomposite hydrogel

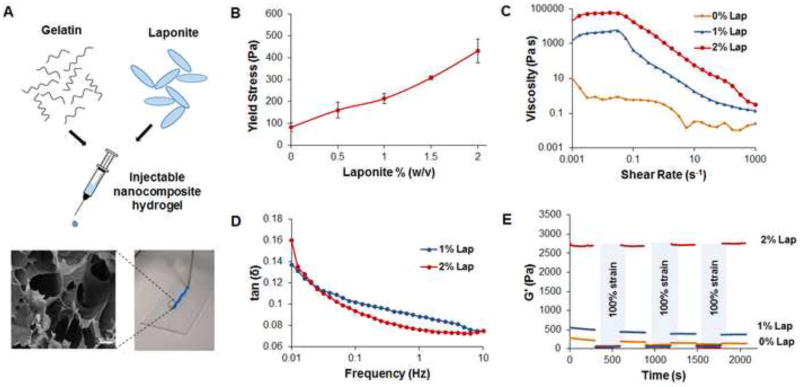

Strategic combinations of polymers and nanoparticles allow scientists to develop injectable physically crosslinked hydrogels to control the delivery of several types of biomolecules and therapeutic agents for tissue regeneration. Polymers and nanomaterials can be mixed before the gelation to form nanocomposite systems that can be easily injected through a needle. This avoids the use of complex fabrication methods that can be difficult to translate into the clinic, as well as, the need for invasive surgery for their administration. [61] In this study, fully exfoliated Laponite® (0, 1, 2% w/v) was combined with gelatin (5% w/v) to form an injectable hydrogel for the delivery of stem cell derived secretome (Fig 3A). After the hydrogel was formed, FT-IR spectra of Laponite®, gelatin, and the nanocomposite hydrogel confirmed the polymer clay interactions through a slight shift in the characteristic Si-O stretching peak from 1013 cm−1 to a lower frequency of 1006 cm−1 (Fig S1A). This peak shift has been reported to be seen from other nanocomposite hydrogels containing Laponite®, as well. [62, 63] A complimentary analysis of the nanocomposite hydrogel’s elemental composition using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) established the presence of silicon (Si) and magnesium (Mg) therefore, confirming the contribution of the Laponite® nanoparticles to the structural network of the hydrogel (Fig S1B and S1C). [64] To assess the effect of Laponite® on the viscoelastic behavior of the nanocomposite hydrogel several rheological techniques were used. Initial strain sweeps were carried out to determine the linear viscoelastic region for each of the Laponite® concentrations (Fig S2A). Frequency sweep measurements from 0.01 to 10 Hz at a strain of 1% showed consistent storage moduli (G’) approximately one magnitude higher than loss moduli (G’’), irrespective of the frequency (Fig S2B). This behavior indicates that, at the concentrations used, gelatin and Laponite® are able to form hydrogel networks that exhibit solid-like behavior (G’>G’’). [65] However, at higher oscillatory strain percentages the material begins to flow (G’<G’’) illustrating yielding behavior which is an important parameter for designing injectable hydrogel systems. The yield stress approximately doubled as the concentration of Laponite® increased from 1% to 2% within the nanocomposite hydrogel (Fig 3B). In addition, a similar trend was seen in the viscosity testing where an increase from 1% w/v to 2% w/v Laponite® caused the viscosity to rise by an order of magnitude (Fig 3C). One probable cause for this direct correlation between the increased viscosity and the Laponite® concentration is the physical crosslinking occurring between the predominately negatively charged Laponite® disks and the positive charges of lysine ε-amino groups of gelatin. This crosslinking can be confirmed by monitoring the change in the loss factor, tan δ = G’’/G’, over a range of oscillatory frequencies. As the concentration of Laponite® increased from 1% w/v to 2% w/v, there was also a slight decrease in tan δ at a frequency of 0.1 to 10 Hz (Fig 3D). This reduction in tan δ, combined with the significant rise in G’ with greater concentrations of Laponite®, confirms that Laponite® increases the crosslinking density within the nanocomposite hydrogel. This behavior has been observed with several other nanocomposite hydrogels containing various hydrophilic polymers and Laponite®. [66, 67] Although the exact interactions are not known, generally researchers consider hydrogen bonding, dipole, and ionic interactions to play a significant role in the physically crosslinked networks between polymers and nanosilicates. [26, 66]. These interactions are more likely to occur at higher concentrations of Laponite® dictating a difference in the degradation profiles as observed in this study. Specifically, after 2 weeks the nanocomposite hydrogels containing 1% nanoclay were significantly degraded unlike the 2% nanoclay hydrogels which showed minimal degradation (Fig S3A). As well as improving the stability of the hydrogel, Laponite® can also influence the retention of proteins within the hydrogel matrix. This control over the amount of protein released is beneficial to treat cardiovascular injuries that require a prolonged presence of bioactive molecules consistently delivered to the damaged tissue. To prove this concept, we studied the influence of Laponite® concentration on the release of the model protein (myoglobin) and observed that a concentration of 2% nanoclay was able to reduce the percentage of protein released when compared to the formulation containing the lower Laponite® concentration (Fig S3B). As mentioned previously, the ability for a hydrogel to pass readily through a needle is an important parameter to enable a straightforward delivery to the therapeutic site. The shear thinning behavior exhibited by this nanocomposite hydrogel at shear rates greater than 0.1 s−1 confirms its injectability (Fig 3D). However, after injection rapid recovery of the hydrogel stiffness is imperative to prevent the material from flowing out of the therapeutic site. Therefore, recovery testing was carried out with each nanocomposite hydrogel by monitoring the G’ during three cycles of high (100%) followed by low (1%) oscillatory strain for five minutes each (Fig 3E). At the beginning of each high strain cycle, all of the G’ values dropped to below 100 Pa, however, the hydrogels that contained 1% w/v and 2% w/v of Laponite® regained a significant amount of their stiffness directly after the strain was decreased to 1% w/v. Specifically, after the first high strain cycle, the nanocomposite hydrogel that contained 1% w/v Laponite® exhibited a G’ value that was only 20% lower than the initial value during the primary low strain cycle. Despite this recovery behavior, after three cycles of high strain the hydrogel was only able to recover 66% of the original G’ value. Interestingly, this reduction in G’ values after multiple cycles of high strain was not observed in the nanocomposite hydrogel containing 2% w/v Laponite®. This hydrogel was able to recover to 98–99% of the initial G’ value after each high strain cycle. These results confirm the thixotropic behavior of the hydrogel systems containing Laponite® previously observed with similar physically crosslinked hydrogel systems. [65, 67] In addition to the recovery studies, the stiffness of the hydrogel system was monitored from 25 °C to 40 °C in order to evaluate the mechanical integrity of the nanocomposite hydrogel at the physiological temperature of 37°C (Fig S2C). As expected there was a slight decrease in the G’ among all the groups at temperatures above 35°C however, this decrease was less pronounced in the hydrogels containing 2% Laponite® (Fig S2D). This indicates that the Laponite® is crucial in maintaining the integrity of the hydrogel even at temperatures where gelatin is known to be in a sol state. Taken together, these studies further established that gelatin and Laponite® have the ability to form a robust injectable hydrogel network for regenerative medicine applications. Lastly, in vitro biocompatibility testing with the different hydrogel formulations was carried out using an MTS assay. Briefly, HUVECs were seeded with complete endothelial growth media and allowed to reach confluency prior the addition of the respective nanocomposite hydrogel. After 1 day, 3 days and 5 days, no significant difference in cell number between the groups was observed indicating that the hydrogel did not produce any cytotoxic effects irrespective of the concentration of Laponite® included in the network (Fig S5A). These results were also supported by immunofluorescent staining for F-actin of the HUVECs which showed no morphological difference between the groups (Fig S5B). Overall, due to the superior rheological properties and absence of cytotoxicity, the nanocomposite hydrogel containing 2% w/v of Laponite® was chosen for further in vivo testing.

Figure 3.

Effect of Laponite® on the rheological properties of the nanocomposite hydrogel. A) Schematic representation of the injectable hydrogel main components and representative image of the injectable nanocomposite hydrogel using a 22 gauge needle along with SEM image illustrating the hydrogel porosity. Scale bar: 100 µm B) Yield stress values of the nanocomposite hydrogel plotted as a function of the Laponite® concentration. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n=3). C) Viscosity curves showing an increase in the viscosity as the Laponite® concentration increases D) Representative Tan δ (G”/G’) profiles as a function of the frequency (0.01–10 Hz) for the different system containing a different concentration of Laponite®. A decrease in the tan δ was observed for the system containing Laponite® 2% w/v, which is indicative of a higher degree of physical crosslinking. E) Recovery properties of the hydrogels were assessed by monitoring the storage moduli of the hydrogels while subjecting them to alternating high (100%) and low (1%) strain. Laponite® was found to greatly enhance the thixotropic behavior of the hydrogels.

3.4 In Vivo Biocompatibility of Injectable Nanocomposite Hydrogel

To ensure that no significant immune response was induced by the nanocomposite hydrogel, preliminary in vivo biocompatibility tests in immunocompetent rats were performed (n=5). Immunohistochemical staining of the myocardium indicated that there was no substantial inflammation (TNFα) or cardiomyocyte damage (TUNEL) caused by the hydrogel injections (Fig S6 and S7), 14 days post infarction. Similar results were obtained by qPCR that indicated that there was no significant difference in proinflammatory (TNFα, miR-146, miR-155) or cardiomyocyte apoptotic (miR-145, Cyclin D1, Rb1) gene and miRNA expression between the control and animals injected with the hydrogel (Fig S8). Lastly, upon injection of the nanocomposite hydrogel, no inhibition of proper cardiac function was observed (Fig S9). Therefore, based on these combined results we can conclude that the nanocomposite hydrogel is biocompatible as seen in previous regenerative medicine studies. [26]

3.5 In vivo Therapeutic Efficacy in Myocardial Infarcted Rat Model

Despite the multiple clinical trials and preclinical studies investigating stem cell therapy for the treatment of AMI, outcomes thus far have been sub-optimal due to the complex pathology resulting from this CVD and the lack of retention of the cells at the delivery site. Recent research has established paracrine signaling as the widely accepted mediator of the positive outcomes that have been observed from stem cell therapy in the heart. [5, 9] However, using the cocktail of therapeutic biomolecules produced by stem cells in vitro (secretome) to promote myocardial regeneration post acuteMI is still in its infancy. [68, 69] Specifically, there are few publications dedicated to using biomaterials in combination with secretome despite the well-established importance of biomaterial use in initiating an optimal local regenerative response in the heart upon cell, gene, or growth factor delivery. [16, 25] Therefore, in this study, we aimed to develop a biocompatible, injectable hydrogel containing stem cell-derived secretome for acute MI therapy. Taking advantage of the relatively high protein adsorption capacity of Laponite® and its ability to contribute to hydrogel stiffness we developed a nanocomposite hydrogel loaded with stem cell derived secretome and hypothesized that it would successfully treat pathologies associated with acute MI in vivo.

Subsequent studies to investigate the therapeutic efficacy of the secretome loaded nanocomposite hydrogel were assessed in an acute MI rat model using established methods (Fig 4A). [19, 34] Preliminary baseline echocardiographs (Fig 4A and 4B) were collected (EF% ≈ 50, FS% ≈ 27, and CO ≈ 42 L/min for all groups) and subsequent echocardiographs were taken at day 3, 7, 14 and 21 (Fig 4A). Initially, there was no significant difference in heart function observed on day 3 (Fig 4C–E). However, on day 7 all three cardiac function parameters were significantly increased in the nSi Gel+ group (EF%=56.9, FS%=31.1, CO=10.9 L/min) with respect to the control and nSi Gel groups (Fig 4C–E). This trend continued on day 14 with the exception of the cardiac output (EF%= 57.0±4.6, FS% = 31.1±3.3) (Fig 4C–E). Once again on day 21, all three heart function parameters significantly improved in the nSi Gel+ group (EF%= 62.8±3.0, FS% = 33.8±2.8, CO = 66.7±6.6) with respect to the control (EF%= 45.2±5.0, FS% = 23.5±3.1, CO = 48.3±7.6) and the nSi Gel (EF%= 46.7±6.8, FS% = 23.4±3.8, CO = 50.2±13.2) groups (Fig 4C–E). These three assessments are vital systolic functional parameters that are commonly used to assess the extent by which acute MI pathologies have affected myocardial function. [68, 70–72] Therefore, we can confidently conclude that the secretome loaded nanocomposite hydrogel is able to improve heart function after the characteristic initial decline caused by acute MI cardiac remodeling. In addition, we observed that the secretome loaded nanocomposite hydrogel was able to improve cardiac function significantly better than the injection of the secretome solution alone indicated by the EF% of 62.8±3.0 % and 50.5±3.2 % at day 21 (Fig S10), respectively. This confirms the importance of the hydrogel delivery vehicle for a greater therapeutic outcome.

Figure 4.

Positive effect of the secretome loaded nanocomposite hydrogel on cardiac function in vivo. A) Schematic representing the design of the study. Specifically, either phosphate buffer saline (No Treatment), the nanocomposite hydrogel (nSi Gel), or the secretome loaded nanocomposite hydrogel (nSi Gel+) were injected into the peri-infarct region of rat hearts with an induced acute myocardial infarction 15 minutes post infarction. Subsequent echocardiographs were taken at day 3, 7, 14, and 21 followed by histomorphometric studies of the rat hearts. B) Representative echocardiograph data for each test group used to calculate the cardiac function parameters. C) Calculated heart ejection fractions (EF %) at each time point. A significant increase in the nSi Gel+ group EF% was observed when compared to the nSi Gel group. D) Fractional shortening (FS %) calculations at each time point. The nSi Gel+ showed a substantial increase in FS% in comparison to the nSi Gel group at each time point except at day 3. E) Cardiac output (L/min) was monitored for each group throughout the study. The cardiac output for the nSi Gel+ group was significantly greater than the nSi Gel group on days 7 and 21. Data are expressed as mean value ± standard deviation f, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, (n = 5).

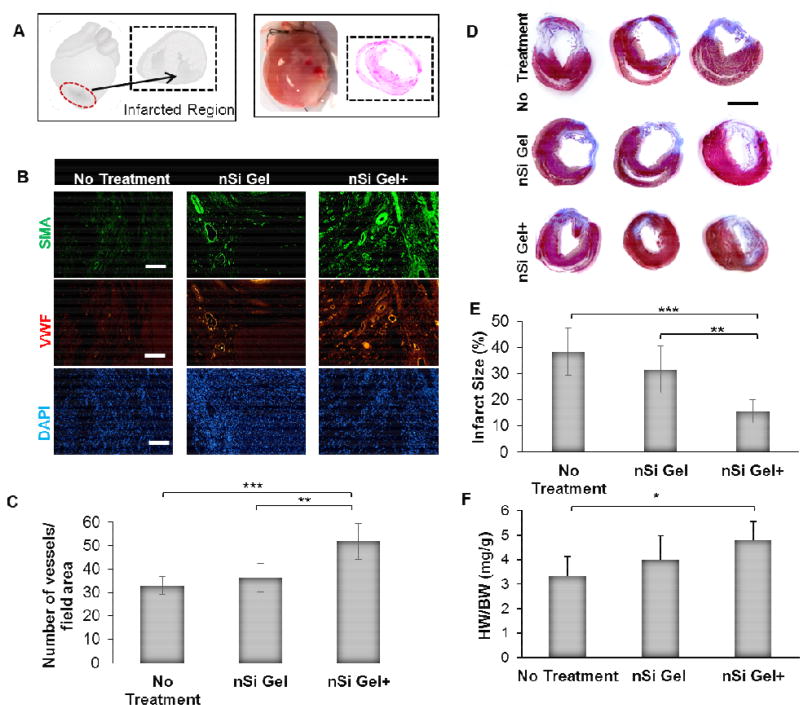

As mentioned previously, vascular repair mechanisms constitute a paramount means to reduce myocardial injury and therefore, they are necessary for the improvement of the heart function after acute MI. [68, 69] In order to assess the therapeutic potential of the nSi Gel+ to promote angiogenesis within the infarcted heart (Fig 5A) of an acute MI rat model, the animals were sacrificed, and the myocardium was stained for vWF and SMA within the peri-infarct region (Fig 5B). A significantly larger density of vWF and SMA positive vessels was seen in the animals treated with the nSi Gel+ when compared to the nSi Gel and control group (Fig 5C). In addition, the increased presence of SMA staining was also observed in the nSi Gel+ group (Fig 5B).

Figure 5.

Assessment of the in vivo pro-angiogenic and scar area reduction capability of the secretome loaded nanocomposite hydrogel. A) An illustration (left) and image (right) of the infarcted region of the acute myocardial infarction model where either phosphate buffer saline (No Treatment), nanocomposite hydrogel (nSi Gel), or secretome loaded nanocomposite hydrogel (nSi Gel+) was injected. B) Representative micrographs of immunohistochemically stained sections of the peri-infarct region highlighting cell nuclei (DAPI), endothelial cells (vWF) and mural cells (SMA), 21 days post treatment injection. Scale bar: 100 µm. C) Quantification of vessels stained positive for vWF+ and SMA indicating a significant increase in the blood vessel density in the hearts that received the nSi Gel and nSi Gel+ treatment. D) Characteristic Masson’s trichrome stained cross-sections of the rat hearts displaying the scar formation in each group. Scale bar: 5 mm. E) The percentage of the myocardium that was replaced with infarcted tissue was quantified for each test group. A significant decrease in infarct size was observed in the nSi Gel and nSi Gel+ group. F) The heart weight to body weight ratio (HW/BW) was calculated for each group and a significant increase in the ratio was observed in the nSi Gel+ group when compared to the control. Data expressed as mean value ± standard deviation * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001, (n = 5).

These results indicate that there was not only more capillary formation within the nSi Gel+ group but also the presence of more mature vessel morphology shown by the SMA staining. These results indicate that the proangiogenic growth factors and cytokines detected within the stem cell derived secretome were indeed able to promote angiogenesis in the heart post-acute MI when delivered using the nanocomposite hydrogel. Another result of acute MI that impairs proper myocardial function is the replacement of functional myocardium with fibrous scar tissue known as cardiac remodeling that is caused by cardiomyocyte necrosis. [19, 69, 73] A histological analysis of the hearts from each group was used to assess if the nSi Gel+ was able to reduce the extent of this cardiac remodeling (Fig 5D). The results showed that the nSi Gel+ was able to significantly limit the infarct size to 15.6±4.5% of the total heart while the infarct accounted for 38.4±9.0% and 31.6±9.0% of the control and nSi Gel hearts, respectively (Fig 5E). These results were further supported by the calculated heart weight to body weight ratios that indicated the ratio obtained from the nSi Gel+ group hearts was significantly greater (Fig 5F). This decrease in cardiac fibrosis combined with an increase in angiogenesis has been associated with the improvement of the cardiac function post-acute MI in other studies, [19, 68, 69, 73] and may represent the potential mechanisms that likely facilitated the improvement in cardiac function that we observed in this work.

4. Conclusion

We have successfully designed an injectable therapeutic nanocomposite hydrogel that represents a promising alternative to traditional stem cell therapy for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction. The shear thinning hydrogel was made by mixing the gelatin solution with a Laponite® dispersion and was used as a carrier for the delivery of stem cell derived-secretome. As expected, the increase in Laponite® concentration up to 2% w/v was responsible for the formation of a highly physically crosslinked gel which could sustain high strain and recover its original stiffness once the strain was reduced to 1%. This property is essential to prevent the material from flowing out of the therapeutic site once injected and thus enabling longer retention of the secretome.

Additionally, the secretome was easily isolated from hASCs cultured as spheroids using PDMS microwell devices. Spheroids secreted a more concentrated and diverse composition of proangiogenic and cardioprotective growth factors, proteins, and cytokines when compared to cells grown in a traditional 2D monolayer environment. Therefore, spheroid culture provides an ideal opportunity to deliberately adjust the secretome composition to directly promote key therapeutic processes needed for cardiac regenerative medicine applications. The injection of the secretome loaded hydrogel in the peri-infarct area in an acute myocardial infarction rat model promoted increased angiogenesis, reduction in cardiac remodeling, and cardioprotection in vitro and in vivo. Overall these results suggest that the stem cell-derived secretome loaded hydrogel represents a viable option for the promotion of myocardial regeneration and myocardial therapy post-acute MI.

Supplementary Material

Statement of significance.

Stem cell based-therapies represent a possible solution to repair damaged myocardial tissue by promoting cardioprotection, angiogenesis, and reduced fibrosis. However, recent evidence indicates that most of the positive outcomes are likely due to the release of paracrine factors (cytokines, growth factors, and exosomes) from the cells and not because of the local engraftment of stem cells. This cocktail of essential growth factors and paracrine signals is known as secretome can be isolated in vitro, and the biomolecule composition can be controlled by varying stem-cell culture conditions. Here, we propose a straightforward strategy to deliver secretome produced from hASCs by using a nanocomposite injectable hydrogel made of gelatin and Laponite®. The designed secretome-loaded hydrogel represents a promising alternative to traditional stem cell therapy for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction.

Acknowledgments

RW acknowledges the financial support from NIH-Biotechnology Predoctoral Research Training Program (T32-GM008359). RPHA acknowledges support from National Institute of Health (NIH) grant 1R01HL-10690. AP acknowledges an investigator grant provided by the Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the NIH Award Number P20GM103638 and Umbilical Cord Matrix Project fund from State of Kansas.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, de Ferranti S, Després J-P, Fullerton HJ, Howard VJ. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29–e322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pagidipati NJ, Gaziano TA. Estimating deaths from cardiovascular disease: a review of global methodologies of mortality measurement. Circulation. 2013;127(6):749–756. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.128413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moran AE, Forouzanfar MH, Roth G, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Flaxman A, Murray CJ, Naghavi M. The global burden of ischemic heart disease in 1990 and 2010: the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Circulation. 2014 doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004046. CIRCULATIONAHA. 113.004046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karantalis V, Hare JM. Use of mesenchymal stem cells for therapy of cardiac disease. Circulation research. 2015;116(8):1413–1430. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.303614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gnecchi M, He H, Noiseux N, Liang OD, Zhang L, Morello F, Mu H, Melo LG, Pratt RE, Ingwall JS, Dzau VJ. Evidence supporting paracrine hypothesis for Akt-modified mesenchymal stem cell-mediated cardiac protection and functional improvement. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2006;20(6):661–9. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5211com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mirotsou M, Jayawardena TM, Schmeckpeper J, Gnecchi M, Dzau VJ. Paracrine mechanisms of stem cell reparative and regenerative actions in the heart. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2011;50(2):280–289. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uemura R, Xu M, Ahmad N, Ashraf M. Bone marrow stem cells prevent left ventricular remodeling of ischemic heart through paracrine signaling. Circulation research. 2006;98(11):1414–21. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000225952.61196.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stastna M, Van Eyk JE. Investigating the Secretome Lessons About the Cells That Comprise the Heart. Circulation: Cardiovascular Genetics. 2012;5(1):o8–o18. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.960187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ranganath SH, Levy O, Inamdar MS, Karp JM. Harnessing the mesenchymal stem cell secretome for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cell stem cell. 2012;10(3):244–258. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tran C, Damaser MS. Stem cells as drug delivery methods: application of stem cell secretome for regeneration. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2015;82:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tous E, Purcell B, Ifkovits JL, Burdick JA. Injectable acellular hydrogels for cardiac repair. Journal of cardiovascular translational research. 2011;4(5):528–542. doi: 10.1007/s12265-011-9291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roche ET, Hastings CL, Lewin SA, Shvartsman DE, Brudno Y, Vasilyev NV, O'Brien FJ, Walsh CJ, Duffy GP, Mooney DJ. Comparison of biomaterial delivery vehicles for improving acute retention of stem cells in the infarcted heart. Biomaterials. 2014;35(25):6850–6858. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.04.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hasan A, Waters R, Roula B, Dana R, Yara S, Alexandre T, Paul A. Engineered Biomaterials to Enhance Stem Cell-Based Cardiac Tissue Engineering and Therapy. Macromolecular Bioscience. 2016;16(7):958–977. doi: 10.1002/mabi.201500396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang J, Shen D, Caranasos TG, Wang Z, Vandergriff AC, Allen TA, Hensley MT, Dinh P-U, Cores J, Li T-S. Therapeutic microparticles functionalized with biomimetic cardiac stem cell membranes and secretome. Nature communications. 2017;8:13724. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo L, Tang J, Nishi K, Yan C, Dinh P-U, Cores J, Kudo T, Zhang J, Li T-S, Cheng K. Fabrication of synthetic mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of acute myocardial infarction in micenovelty and significance. Circulation research. 2017;120(11):1768–1775. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasan A, Khattab A, Islam MA, Hweij KA, Zeitouny J, Waters R, Sayegh M, Hossain MM, Paul A. Injectable hydrogels for cardiac tissue repair after myocardial infarction. Advanced Science. 2015;2(11) doi: 10.1002/advs.201500122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pacelli S, Paolicelli P, Dreesen I, Kobayashi S, Vitalone A, Casadei MA. Injectable and photocross-linkable gels based on gellan gum methacrylate: A new tool for biomedical application. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2015;72:1335–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul A. Nanocomposite hydrogels: an emerging biomimetic platform for myocardial therapy and tissue engineering. Nanomedicine. 2015;10(9):1371–1374. doi: 10.2217/nnm.15.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paul A, Hasan A, Kindi HA, Gaharwar AK, Rao VT, Nikkhah M, Shin SR, Krafft D, Dokmeci MR, Shum-Tim D. Injectable graphene oxide/hydrogel-based angiogenic gene delivery system for vasculogenesis and cardiac repair. ACS nano. 2014;8(8):8050–8062. doi: 10.1021/nn5020787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su D, Jiang L, Chen X, Dong J, Shao Z. Enhancing the Gelation and Bioactivity of Injectable Silk Fibroin Hydrogel with Laponite Nanoplatelets. ACS applied materials & interfaces. 2016;8(15):9619–9628. doi: 10.1021/acsami.6b00891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulyasasmita W, Cai L, Hori Y, Heilshorn SC. Avidity-controlled delivery of angiogenic peptides from injectable molecular-recognition hydrogels. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2014;20(15–16):2102–2114. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2013.0357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitlow J, Pacelli S, Paul A. Polymeric Nanohybrids as a New Class of Therapeutic Biotransporters. Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics. 2016 doi: 10.1002/macp.201500464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pacelli S, Manoharan V, Desalvo A, Lomis N, Jodha KS, Prakash S, Paul A. Tailoring biomaterial surface properties to modulate host-implant interactions: implication in cardiovascular and bone therapy. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 2016;4(9):1586–1599. doi: 10.1039/C5TB01686J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krishna KV, Ménard-Moyon C, Verma S, Bianco A. Graphene-based nanomaterials for nanobiotechnology and biomedical applications. Nanomedicine : nanotechnology, biology, and medicine. 2013;8(10):1669–1688. doi: 10.2217/nnm.13.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waters R, Pacelli S, Maloney R, Medhi I, Ahmed RPH, Paul A. Stem cell secretome-rich nanoclay hydrogel: a dual action therapy for cardiovascular regeneration. Nanoscale. 2016;8(14):7371–7376. doi: 10.1039/c5nr07806g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding X, Gao J, Wang Z, Awada H, Wang Y. A shear-thinning hydrogel that extends in vivo bioactivity of FGF2. Biomaterials. 2016;111:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawson JI, Kanczler JM, Yang XB, Attard GS, Oreffo RO. Clay gels for the delivery of regenerative microenvironments. Advanced Materials. 2011;23(29):3304–3308. doi: 10.1002/adma.201100968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gibbs D, Black C, Hulsart-Billstrom G, Shi P, Scarpa E, Oreffo R, Dawson J. Bone induction at physiological doses of BMP through localization by clay nanoparticle gels. Biomaterials. 2016;99:16–23. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amable PR, Teixeira MVT, Carias RBV, Granjeiro JM, Borojevic R. Protein synthesis and secretion in human mesenchymal cells derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue and Wharton’s jelly. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2014;5(2):53. doi: 10.1186/scrt442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Corrente F, Amara HMA, Pacelli S, Paolicelli P, Casadei MA. Novel injectable and in situ cross-linkable hydrogels of dextran methacrylate and scleroglucan derivatives: Preparation and characterization. Carbohydrate polymers. 2013;92(2):1033–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watson BM, Kasper FK, Engel PS, Mikos AG. Synthesis and characterization of injectable, biodegradable, phosphate-containing, chemically cross-linkable, thermoresponsive macromers for bone tissue engineering. Biomacromolecules. 2014;15(5):1788–1796. doi: 10.1021/bm500175e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang CC, Pan WY, Tseng MT, Lin KJ, Yang YP, Tsai HW, Hwang SM, Chang Y, Wei HJ, Sung HW. Enhancement of cell adhesion, retention, and survival of HUVEC/cbMSC aggregates that are transplanted in ischemic tissues by concurrent delivery of an antioxidant for therapeutic angiogenesis. Biomaterials. 2016;74:53–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Durrani S, Haider KH, Ahmed RPH, Jiang S, Ashraf M. Cytoprotective and Proangiogenic Activity of Ex-Vivo Netrin-1 Transgene Overexpression Protects the Heart Against Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury. Stem Cells and Development. 2012;21(10):1769–1778. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul A, Binsalamah ZM, Khan AA, Abbasia S, Elias CB, Shum-Tim D, Prakash S. A nanobiohybrid complex of recombinant baculovirus and Tat/DNA nanoparticles for delivery of Ang-1 transgene in myocardial infarction therapy. Biomaterials. 2011;32(32):8304–8318. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arif M, Pandey R, Alam P, Jiang S, Sadayappan S, Paul A, Ahmed RPH. MicroRNA-210-mediated proliferation, survival, and angiogenesis promote cardiac repair post myocardial infarction in rodents. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany) 2017 doi: 10.1007/s00109-017-1591-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pandey R, Velasquez S, Durrani S, Jiang M, Neiman M, Crocker JS, Benoit JB, Rubinstein J, Paul A, Ahmed RP. MicroRNA-1825 induces proliferation of adult cardiomyocytes and promotes cardiac regeneration post ischemic injury. American journal of translational research. 2017;9(6):3120–3137. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paul A, Hasan A, Kindi HA, Gaharwar AK, Rao VTS, Nikkhah M, Shin SR, Krafft D, Dokmeci MR, Shum-Tim D, Khademhosseini A. Injectable Graphene Oxide/Hydrogel-Based Angiogenic Gene Delivery System for Vasculogenesis and Cardiac Repair. ACS Nano. 2014;8(8):8050–8062. doi: 10.1021/nn5020787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haider HK, Lee Y-J, Jiang S, Ahmed RPH, Ryon M, Ashraf M. Phosphodiesterase inhibition with tadalafil provides longer and sustained protection of stem cells. American Journal of Physiology - Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2010;299(5):H1395–H1404. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00437.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frith JE, Thomson B, Genever PG. Dynamic three-dimensional culture methods enhance mesenchymal stem cell properties and increase therapeutic potential. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods. 2009;16(4):735–749. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cesarz Z, Tamama K. Spheroid culture of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem cells international. 2015;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/9176357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shearier E, Xing Q, Qian Z, Zhao F. Physiologically Low Oxygen Enhances Biomolecule Production and Stemness of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Spheroids. Tissue Engineering Part C: Methods. 2016;22(4):360–369. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2015.0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Potapova IA, Gaudette GR, Brink PR, Robinson RB, Rosen MR, Cohen IS, Doronin SV. Mesenchymal stem cells support migration, extracellular matrix invasion, proliferation, and survival of endothelial cells in vitro. Stem cells. 2007;25(7):1761–1768. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okada M, Oba Y, Yamawaki H. Endostatin stimulates proliferation and migration of adult rat cardiac fibroblasts through PI3K/Akt pathway. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2015;750:20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Isobe K, Kuba K, Maejima Y, Suzuki J-i, Kubota S, Isobe M. Inhibition of endostatin/collagen XVIII deteriorates left ventricular remodeling and heart failure in rat myocardial infarction model. Circulation Journal. 2010;74(1):109–119. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonnenberg S, Rane AA, Liu CJ, Rao N, Agmon G, Suarez S, Wang R, Munoz A, Bajaj V, Zhang S, Braden R, Schup-Magoffin PJ, Kwan OL, DeMaria AN, Cochran JR, Christman KL. Delivery of an engineered HGF fragment in an extracellular matrix-derived hydrogel prevents negative LV remodeling post-myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 2015;45:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nakamura T, Mizuno S, Matsumoto K, Sawa Y, Matsuda H, Nakamura T. Myocardial protection from ischemia/reperfusion injury by endogenous and exogenous HGF. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2000;106(12):1511–1519. doi: 10.1172/JCI10226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakamura T, Matsumoto K, Mizuno S, Sawa Y, Matsuda H, Nakamura T. Hepatocyte growth factor prevents tissue fibrosis, remodeling, and dysfunction in cardiomyopathic hamster hearts. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2005;288(5):H2131–H2139. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01239.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taniyama Y, Morishita R, Aoki M, Hiraoka K, Yamasaki K, Hashiya N, Matsumoto K, Nakamura T, Kaneda Y, Ogihara T. Angiogenesis and antifibrotic action by hepatocyte growth factor in cardiomyopathy. Hypertension. 2002;40(1):47–53. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.0000020755.56955.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ueda H, Nakamura T, Matsumoto K, Sawa Y, Matsuda H, Nakamura T. A potential cardioprotective role of hepatocyte growth factor in myocardial infarction in rats. Cardiovascular research. 2001;51(1):41–50. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(01)00272-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marsano A, Maidhof R, Luo J, Fujikara K, Konofagou EE, Banfi A, Vunjak-Novakovic G. The effect of controlled expression of VEGF by transduced myoblasts in a cardiac patch on vascularization in a mouse model of myocardial infarction. Biomaterials. 2013;34(2):393–401. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wu J, Zeng F, Huang X-P, Chung JC-Y, Konecny F, Weisel RD, Li R-K. Infarct stabilization and cardiac repair with a VEGF-conjugated, injectable hydrogel. Biomaterials. 2011;32(2):579–586. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang Y, Shi C, Hou X, Zhao Y, Chen B, Tan B, Deng Z, Li Q, Liu J, Xiao Z, Miao Q, Dai J. Modified VEGF targets the ischemic myocardium and promotes functional recovery after myocardial infarction. Journal of Controlled Release. 2015;213:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhao T, Zhao W, Chen Y, Ahokas RA, Sun Y. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A: Role on cardiac angiogenesis following myocardial infarction. Microvascular Research. 2010;80(2):188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cohn JN, Ferrari R, Sharpe N. Cardiac remodeling--concepts and clinical implications: a consensus paper from an international forum on cardiac remodeling. Behalf of an International Forum on Cardiac Remodeling. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2000;35(3):569–82. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00630-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kurrelmeyer K, Kalra D, Bozkurt B, Wang F, Dibbs Z, Seta Y, Baumgarten G, Engle D, Sivasubramanian N, Mann DL. Cardiac remodeling as a consequence and cause of progressive heart failure. Clinical cardiology. 1998;21(S1):14–19. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960211304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Awada HK, Hwang MP, Wang Y. Towards comprehensive cardiac repair and regeneration after myocardial infarction: Aspects to consider and proteins to deliver. Biomaterials. 2016;82:94–112. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deroanne CF, Lapiere CM, Nusgens BV. In vitro tubulogenesis of endothelial cells by relaxation of the coupling extracellular matrix-cytoskeleton. Cardiovascular research. 2001;49(3):647–658. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00233-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Swendeman S, Mendelson K, Weskamp G, Horiuchi K, Deutsch U, Scherle P, Hooper A, Rafii S, Blobel CP. VEGF-A stimulates ADAM17-dependent shedding of VEGFR2 and crosstalk between VEGFR2 and ERK signaling. Circulation research. 2008;103(9):916–918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.184416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]