Abstract

The Western diet contributes to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) pathogenesis. Benzo[a]pyrene (BaP), a prototypical environmental pollutant produced by combustion processes, is present in charcoal-grilled meat. Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) metabolizes BaP, resulting in either detoxication or metabolic activation in a context-dependent manner. To elucidate a role of CYP1A1-BaP in NAFLD pathogenesis, we compared the effects of a Western diet, with or without oral BaP treatment, on the development of NAFLD in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice versus wild-type mice. A Western diet plus BaP induced lipid-droplet accumulation in liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice, but not wild-type mice. The hepatic steatosis observed in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice was associated with increased cholesterol, triglyceride and bile acid levels. Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed Western diet plus BaP had changes in expression of genes involved in bile acid and lipid metabolism, and showed no increase in Cyp1a2 expression but did exhibit enhanced Cyp1b1 mRNA expression, as well as hepatic inflammation. Enhanced BaP metabolic activation, oxidative stress and inflammation may exacerbate metabolic dysfunction in liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice. Thus, Western diet plus BaP induces NAFLD and hepatic inflammation in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice in comparison to wild-type mice, indicating a protective role of CYP1A1 against NAFLD pathogenesis.

Keywords: Benzo[a]pyrene, Western diet, Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Bile acids, Lipogenesis, Inflammation

1. Introduction

The polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) is a prototypical environmental pollutant produced by combustion processes such as cigarette smoke, charcoal-grilled food and coke ovens. BaP is implicated as a causative agent in malignant, inflammatory and metabolic diseases, including lung cancer and atherosclerosis (Miller and Ramos, 2001; Uno and Makishima, 2009). BaP activates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and induces expression of genes involved in xenobiotic metabolism, such as the three cytochrome P450 1 (CYP1) monooxygenases (CYP1A1, CYP1A2 and CYP1B1) (Nebert, 2017). CYP1A1 is involved in both BaP detoxication and metabolic activation, the latter resulting in DNA adduct formation and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production (Miller and Ramos, 2001; Shimada and Fujii-Kuriyama, 2004). In addition to CYP1A1, AHR activation induces expression of other phase I enzymes, such as CYP1A2, CYP1B1 and NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase-1 (NQO1), along with phase II enzymes, including glutathione S-transferase-A1 (GSTA1) (Nebert et al., 2000). Sequential reactions by phase I and phase II enzymes induce effective detoxication of BaP (Shimada, 2006; Uno and Makishima, 2009).

Oral BaP administration induces a higher level of BaP-DNA adduct formation in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Uno et al., 2004), and CYP1A1 overexpression suppresses BaP-DNA adduct formation in hepatocytes (Endo et al., 2008). Thus, oral BaP-induced CYP1A1 activity mediates phase I metabolism in BaP detoxication. In contrast, CYP1A1-null mutant hepatoma cells are resistant to BaP toxicity (Hankinson et al., 1991). Conversion of CYP1-mediated metabolites of BaP by epoxide hydrolase leads to further metabolic activation to potent carcinogens such as BaP-7,8-diol-9,10-epoxide (Conney, 2003; Shimada, 2006; Shimada and Fujii-Kuriyama, 2004). Compensatory induction of CYP1B1 in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice enhances BaP metabolic activation (Nebert et al., 2013; Uno et al., 2006). Therefore, the coordinated expression of phase I and phase II enzymes is required for efficient BaP detoxication.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a major health problem in Western countries, and is a hepatic metabolic disease caused by various factors, including dietary factors such as excess intake of energy, carbohydrates and lipids (Yasutake et al., 2014; Zelber-Sagi et al., 2011). Higher meat intake, specifically grilled meat, is also associated with an increased risk of NAFLD (Miele et al., 2014; Zelber-Sagi et al., 2011). Western-style food items, such as barbecued and fried meats and smoked dried beef, contain significant concentrations of BaP (Anastasio et al., 2004; Aygun and Kabadayi, 2005; Lee and Shim, 2007). The total daily intake level of BaP in a typical Western diet is 125 ng/person/day, corresponding to the levels derived from cigarette smoking (20−40 ng/cigarette) (Uno and Makishima, 2009). In addition to dietary factors, cigarette smoking is a risk factor for NAFLD (Hamabe et al., 2011), and large amounts of smoking residue are deposited in the gastrointestinal tract (Nebert et al., 2013). These findings suggest that dietary BaP might be a factor linking NAFLD pathogenesis with the Western diet. Further, AHR activation by 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin induces NAFLD in mouse models (Angrish et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2010), indicating that BaP increases the incidence of NAFLD by AHR activation. However, it remains unknown how the oral BaP-induced enzyme CYP1A1 is involved in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. In the present study using Cyp1a1(−/−) mice, we investigated the role of CYP1A1 in NAFLD induced by the Western diet combined with oral BaP.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and treatment

C57BL/6J mice were obtained from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan), and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice on >99.8% C57BL/6J genetic background were generated, as described previously (Dalton et al., 2000; Uno et al., 2014). All experiments were conducted using 6- to 7-week-old male mice. Mice were maintained under controlled temperature (23 ± 1 °C) and humidity (45−65%) with free access to water and a control diet (CE-2; CLEA Japan) or a Western diet (CE-2 supplemented with 1.25 g/100g cholesterol, 0.5 g/100g sodium cholate, 12.5 g/100g cocoa butter) (Miura et al., 2001; Uno et al., 2014). BaP (Tokyo Chemical Industry, Tokyo, Japan) was dissolved in corn oil, and the pellets were soaked in control corn oil or BaP-containing corn oil (1.0 mg/ml) for at least 24 hours. The daily oral BaP doses were estimated to be ~12.5 mg/kg/day (Uno et al., 2014). We fed wild-type mice and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice a control diet or a Western diet containing control corn oil or BaP-containing corn oil for 3 or 15 weeks (n = 3−4 for each group). Blood and tissue samples were collected after euthanization with CO2 inhalation. The experimental protocol adhered to the Guidelines for Animal Experiments of the Nihon University School of Medicine and was approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Animal Experimentation at the Nihon University School of Medicine.

2.2. Biochemical tests

Plasma total cholesterol, triglyceride and bile acid levels were quantified with Cholesterol E-Testwako (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka Japan), Triglyceride E-Testwako (Wako Pure Chemical Industries) and Total Bile Acid Testwako (Wako Pure Chemical Industries), respectively. Liver samples (~0.1 g) were homogenized in phosphate-buffered saline, and lipids were extracted with a mixture of chloroform, methanol and water (2:1:0.8) and subjected to biochemical analysis.

2.3. Histology

Liver samples were fixed with 10% paraformaldehyde and embedded with paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, immunostained with anti-F4/80 antibody (Nikken Seil Co., Ltd., Fukuroi, Japan), a Histofine mouse stain kit (Nichirei Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and an AEC substrate kit for peroxidase (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), and then visualized by counterstaining with hematoxylin.

2.4. Reverse transcription and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA extraction was performed using the acid guanidium thiocyanate/phenol/chloroform method, and cDNAs were synthesized using the ImProm-II Reverse Transcription system (Promega Corporation, Madison, WI) (Uno et al., 2014). Real-time polymerase chain reactions were performed on the ABI PRISM 7000 Sequence Detection System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) using Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Primer sequences for mouse genes included Abcb11 (bile-salt-exporter pump; BSEP), Abcc3 (multidrug resistance-associated protein-3; MRP3), Abcc4 (MRP4), Slc51a (organic solute transporter-α; OSTα), Slc51b (OSTβ), Slc10a1 (Na+/taurocholate-cotransporting polypeptide; NTCP), Slco1a1 (organic anion-transporting polypeptide-1A1; OATP1A1), Slco1b2 (OATP1B2), Cyp7a1, Cyp8b1, Cyp27a1, Cyp1a1, Cyp1a2, Cyp1b1, Tnf (tumor necrosis factor; TNF), and Gapdh (glyceroaldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase), as reported previously (Nishida et al., 2009; Ogura et al., 2009; Uno et al., 2006). Primers for other genes (positive and negative strands, respectively) were as follows: Abcg5 (ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter-G5; ABCG5), 5′-GTT GTG AGA TTC TCG TGG TC-3′ and 5′-TGG GCA GGT TTT CTC GAT GA-3′; Abcg8, 5′-ATC TCC AAG CTG TCG TTC CT-3′ and 5′-GGT AGA TCG CAT AGA GTG GA-3′; Srebf1 (sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c; SREBP-1c), 5′-ATC GGC GCG GAA GCT GTC GGG GTA GCG TC-3′ and 5′-ACT GTC TTG GTT GTT GAT GAG CTG GAG CAT-3′; Scd1, Scd2, Scd3 and Scd4 (common primers for all four stearoyl-CoA desaturase (SCD) genes), 5′-TAC CGC TGG CAC ATC AAC TT-3′ and 5′-CCA GTT CTC TTA ATC CTG GC-3′; Acc (acetyl-CoA carboxylase; ACC), 5′-GGT GGT TCT TGG GTT GTG AT-3′ and 5′-CAG CCA AGC GGA TGT AAA CT-3′; Lpl (lipoprotein lipase; LPL), 5′-CTT GAT TTA CAC GGA GGT GG-3′ and 5′-CCT AGC ACA GAA GAT GAC CT-3′; Ephx1 (epoxide hydrolase-1; EPHX1), 5′-CCT GGA AGA TCT GCT GAC TA-3′ and 5′-TGG GCA CAA AGA CCT TCA TC-3′; Gsta1, 5′-CAT CCA CCT ACT GGA AGT TC-3′ and 5′-CCA TCA ATG CAG CTT CAC TG-3′; Nqo1, 5′-ATG CTG CCA TGT ACG ACA AC-3′ and 5′-TGA ATC GGC CAG AGA ATG AC-3′; Cybb [cytochrome b-245, beta polypeptide; CYBB), 5′-CAG AAG ACT CTG TAT GGA CG-3′ and 5′-TGG TGA AAG AGC GGA GTT AG-3′; Nox4 (NADPH oxidase-4; NOX4), 5′-TCG AGA CTT TTC ATT GGG CG-3′ 5′-TCC CAT ATG AGT TGT TCC GG-3′; and Duox2 (dual oxidase-2; DUOX2), 5′-TCC ATC GCT GGA TTG CTA TG-3′ and 5′-AAC TTG GAC CCG TCA TTC AC-3′. The mRNA values were normalized to the Gapdh mRNA levels.

2.5 Western blotting

Plasma membrane fractions from pooled liver samples (n = 3−4 for each group) were prepared with the Plasma Membrane Extraction Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom), subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (20 g/lane), and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Western blot analysis was performed using a polyclonal anti-MRP4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), a polyclonal anti-OATP1A1 antibody and a monoclonal anti-LPL antibody (Abcam), visualized with the ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagents (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, United Kingdom) as reported previously (Uno et al., 2006).

2.6. Measurement of TNF-α protein levels

TNF-α protein levels in liver homogenates were determined with the Quantikine ELISA Mouse TNF-α Immunoassay (Bio-Techne, Minneapolis, MN), and were adjusted with total protein levels measures with a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

2.7. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± S.E.M. We performed one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons, or unpaired two-group Student’s t test, to assess significant differences.

3. Results

3.1. Combined treatment with Western diet and oral BaP induces hepatic steatosis in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice

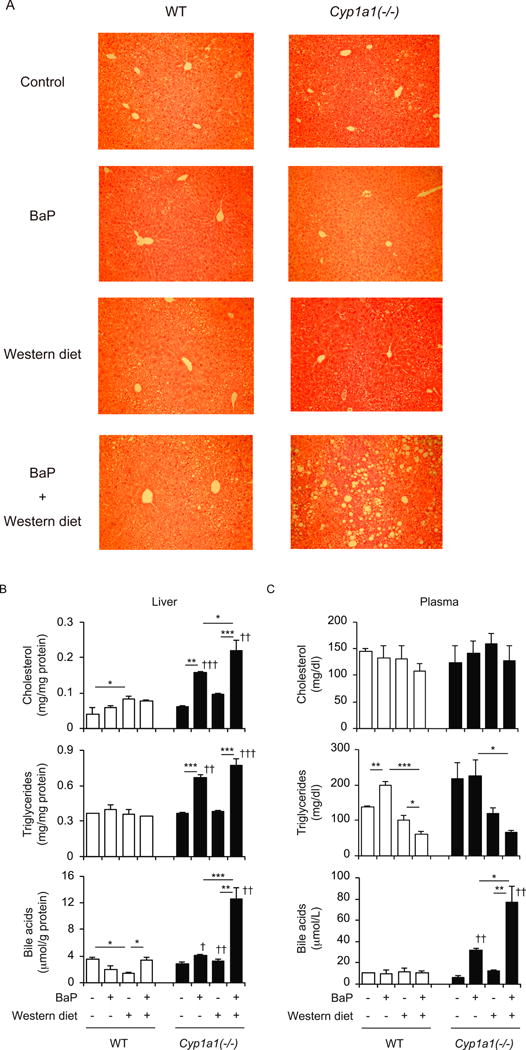

To investigate the role of BaP metabolism by CYP1A1 in the pathogenesis of NAFLD, we first fed wild-type mice and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice a Western diet containing BaP for 15 weeks. The Western diet, oral BaP treatment, or both combined did not induce histological changes in wild-type mice, which have the intact Cyp1a1 gene. While the Western diet alone, or oral BaP alone, had no effect, combined treatment induced accumulation of lipid droplets in the livers of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 1A). Oral BaP increased hepatic cholesterol, triglyceride and bile acid levels in Cyp1a1(−/−), but not wild-type mice, and the combined treatment (Western diet plus BaP) further increased cholesterol and bile acid levels in livers of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 1B). Plasma cholesterol and triglyceride levels were not increased by the Western diet, with or without BaP, and were similar in wild-type mice and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 1C). However, oral BaP increased plasma bile acid levels in Cyp1a1(−/−), but not in wild-type mice. Combined treatment with Western diet and oral BaP elevated bile acid levels further in these mice. Although we observed hepatic lipid accumulation in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet with BaP for 15 weeks, these mice did not have increased plasma alanine aminotransferase levels (Fig. 1D). The combined Western diet and BaP treatment did increase plasma aspartate aminotransferase levels, a similar finding observed in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice receiving a high dose of BaP (Uno et al., 2004), suggesting that these mice have damage in extrahepatic tissues. We next examined the effect of treatment with a Western diet and BaP for 3 weeks, and found that the combined treatment increased plasma aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase levels and hepatic and plasma bile acid levels in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice to levels much higher than in wild-type mice (Fig. 1D and supplementary Fig. 1). As reported previously (Uno et al., 2004), BaP treatment for 3 weeks decreased weight gain in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 1E). The combined treatment with a Western diet and BaP induced weight loss in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice but not in wild-type mice. The combined treatment did not decrease food intake both in wild-type mice and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice. Interestingly, Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet decreased food intake compared to wild-type mice, and addition of BaP to the Western diet increased food intake. Thus, the Western diet containing BaP induces hepatic steatosis, which is associated with dysregulated bile acid and lipid metabolism, and liver cell damage, in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice.

Fig. 1.

Combined treatment with the Western diet and BaP induces hepatic steatosis in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice. (A) Hematoxylin-and-eosin staining of liver samples. (B) Hepatic cholesterol, triglyceride and bile acid levels. (C) Plasma cholesterol, triglyceride and bile acid levels. (D) Plasma aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. (E) Body weight changes and food intake. Wild-type (WT) and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice were fed a control diet versus Western diet, with or without dietary BaP for 3 weeks (D and E) and 15 weeks (A, B, C and D). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons); †† P <0.01, ††† P <0.001 compared to wild-type mice fed the same diet (Student’s t-test).

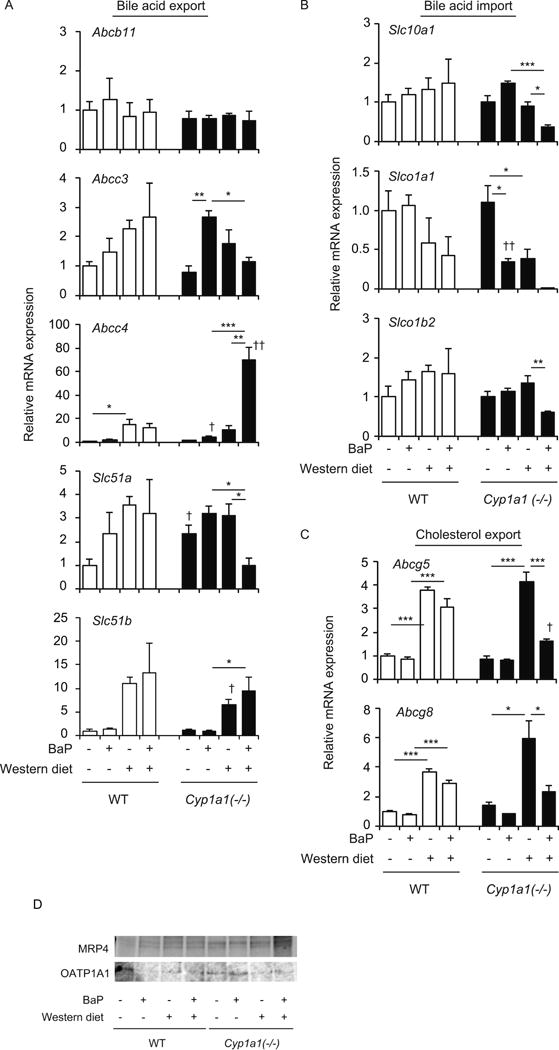

3.2. Effect of combination of the Western diet and oral BaP on expression of bile acid and cholesterol transporter genes

Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet with BaP showed hepatic steatosis associated with lipid accumulation, specifically cholesterol and bile acids (Fig. 1). Since we observed liver dysfunction in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet with BaP for 3 weeks, we next examined the effect of 3-week treatment with a Western diet and BaP on expression of genes involved in bile acid and cholesterol transport. Bile acids are secreted into the bile via the canalicular transporter BSEP (encoded by Abcb11) and, particularly in the context of cholestasis, to the systemic circulation via the basolateral transporters MRP3 (encoded by Abcc3), MRP4 (encoded by Abcc4), and the heterodimer of OSTα (encoded by Slc51a) and OSTβ (encoded by Slc51b) (Zollner et al., 2006). Among these genes, Abcc4 mRNA levels were markedly enhanced in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet with BaP (Fig. 2A). Expression of Slc51b was also induced by the combined treatment, but its levels were similar between wild-type mice and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice. Expression of Abcc3 and Slc51a mRNA levels were decreased in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet with BaP, compared to Cyp1a1(−/−) mice treated with BaP alone, or fed a Western diet alone. Abcb11 mRNA levels did not change in wild-type or Cyp1a1(−/−) mice under any dietary condition.

Fig. 2.

Hepatic expression of genes involved in bile acid and cholesterol transport. (A) mRNA levels of bile-acid-export transporters BSEP (Abcb11), Mrp3, Mrp4, OSTα (Slc51a) and OSTβ (Slc51b). (B) mRNA levels of bile-acid-import transporters NTCP (Scl10a1), OATP1A1 (Slco1a1) and OATP1B2 (Slco1b2). (C) mRNA levels of cholesterol-export transporters Abcg5 and Abcg8. (D) Protein levels of MRP4 and OATP1A1. Wild-type (WT) and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice were fed the control diet versus Western diet, with or without dietary BaP, for 3 weeks. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons); †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 compared to wild-type mice fed the same diet (Student’s t test).

Circulating bile acids are taken up by hepatocytes via NTCP (encoded by Slc10a1), OATP1A1 (encoded by Slco1a1) and OATP1B1 (encoded by Slco1b1) (Zollner et al., 2006). Expression of these import transporters was significantly decreased in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet with BaP (Fig. 2B). The combined treatment with a Western diet and BaP also increased MRP4 protein levels and decreased OATP1A1 protein levels in the liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 2D and supplementary Fig. 2). These findings suggest that decreased expression of Abcc3 and Slc51a mRNA might lead to elevated bile acid levels in hepatocytes and that alterations in Abcc4 expression and import transporters may protect hepatocytes from bile acid accumulation, leading to increased bile acid levels in the blood circulation.

ABCG5 and ABCG8 mediate biliary excretion of cholesterol in hepatocytes (Yu et al., 2003). A Western diet alone increased Abcg5 and Abcg8 mRNA levels in both wild-type and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 2C). Addition of BaP to the Western diet decreased the levels of these transcripts in liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 2C). Diminished expression of Abcg5 and Abcg8 mRNA may account for the cholesterol accumulation in liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice.

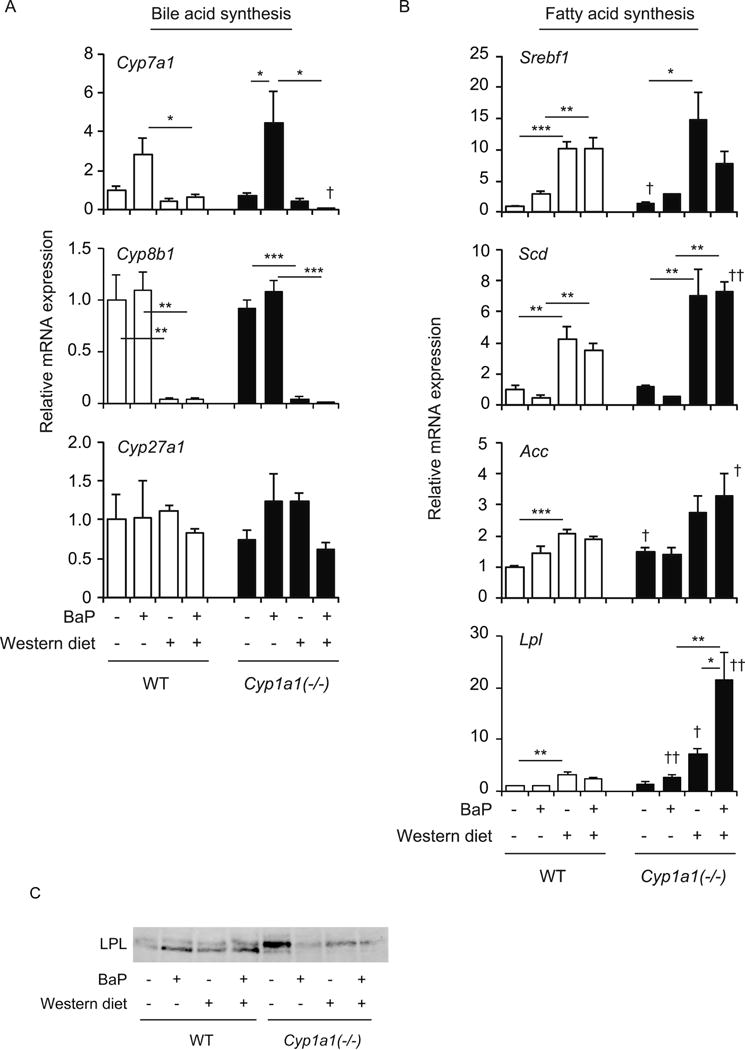

3.3. Effect of a Western diet and oral BaP on expression of genes involved in bile acid and lipid synthesis

We next examined the expression of bile-acid-synthesizing enzyme genes. Interestingly, BaP treatment increased Cyp7a1 expression, and the Western diet plus BaP combined repressed its expression, but there was no difference between wild-type and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 3A). The Western diet, with or without BaP, decreased Cyp8b1 expression in both wild-type and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice. These changes may reflect cellular responses to protect against accumulated bile acids. We saw no significant change in Cyp27a1 expression following in all of the dietary conditions (Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Hepatic expression of genes involved in bile acid and lipid synthesis. (A) mRNA levels of bile-acid-synthesis enzymes Cyp7a1, Cyp8b1 and Cyp27a1. (B) mRNA levels of lipogenesis genes SREBP-1c (Srebf1), SCD (Scd1, Scd2, Scd3 and Scd4), Acc and Lpl. (C) Protein levels of LPL. Wild-type (WT) and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice were fed the control diet versus Western diet, with or without BaP, for 3 weeks. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons); †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 compared to wild-type mice fed the same diet (Student’s t test).

The Western diet increased expression of the lipogenic genes Srebf1 (encoding SREBP-1c), Scd (which includes Scd1, Scd2, Scd3 and Scd4), and Acc in both wild-type and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 3B). Although addition of oral BaP did not further increase these expressions, mRNA levels of Scd and Acc in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed the Western diet with BaP were higher than those in wild-type mice. Treatment with a Western diet alone or oral BaP alone induced slightly higher Lpl mRNA levels in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice, compared to wild-type mice, and the combination of Western diet plus BaP caused a striking increase of Lpl mRNA expression in Cyp1a1(−/−), but not wild-type mice (Fig. 3B). These findings are consistent with the occurrence of hepatic steatosis in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice that had received the Western diet with BaP. We observed increased LPL protein levels in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a control diet compared to wild-type mice (Fig. 3C). BaP treatment decreased LPL protein expression in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice.

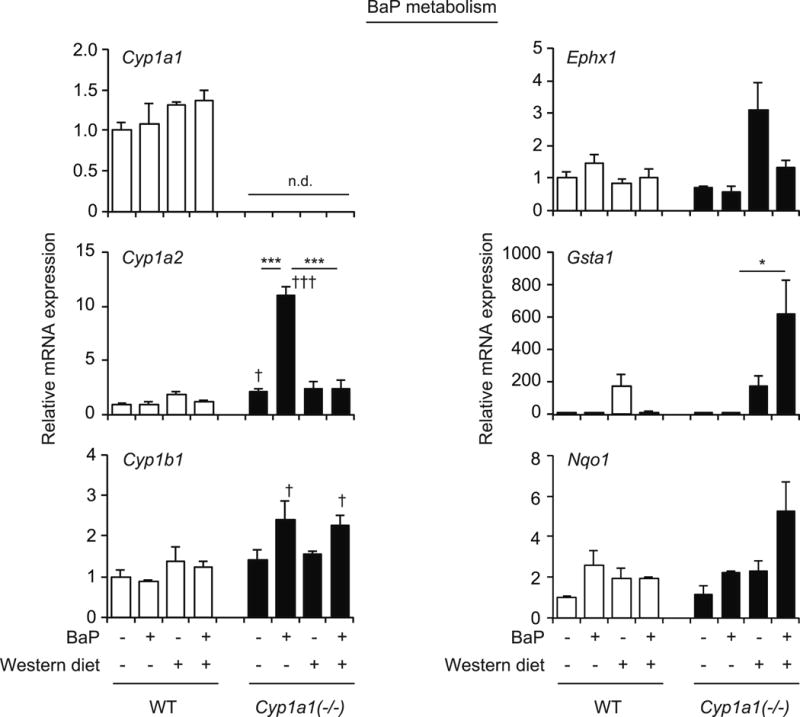

3.4. Effect of combined Western diet plus oral BaP treatment on expression of genes involved in BaP metabolism

We had previously reported that the levels of oxidative stress markers are elevated in the serum of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet with BaP, compared with that in wild-type mice (Uno et al., 2014). BaP metabolic activation is associated with ROS production (Miller and Ramos, 2001), and increased CYP1B1 activity enhances metabolic activation in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Uno et al., 2006). Hence, we examined the expression of genes involved in BaP metabolism. Treatment with the Western diet and/or oral BaP did not change mRNA levels of Cyp1a1, Cyp1a2, Cyp1b1, Ephx1, Gsta1 or Nqo1 in wild-type mice (Fig. 4). As reported previously (Uno et al., 2006), oral BaP treatment did increase mRNA levels of Cyp1a2 and Cyp1b1 in liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice. While the Western diet did not change hepatic expression of Cyp1a2 or Cyp1b1, expression of Cyp1a2, but not Cyp1b1, was decreased in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice receiving the Western diet plus oral BaP (Fig. 4). Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed the Western diet had increased Ephx1 mRNA levels, but addition of oral BaP slightly decreased Ephx1 expression, although this change was not statistically significant. Gsta1 mRNA levels demonstrated a statistically significant elevation in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed Western diet plus BaP, and Nqo1 expression showed the same pattern but was not statistically significant (Fig. 4). These results show that combined treatment with Western diet and BaP changes the hepatic expression of BaP-metabolizing enzymes in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice.

Fig. 4.

Hepatic expression of genes involved in BaP metabolism. mRNA levels of Cyp1a1, Cyp1a2, Cyp1b1, epoxide hydrolase 1 (Ephx1), Gsta1 and Nqo1 in wild-type (WT) and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice receiving the control diet versus Western diet, with or without BaP, for 3 weeks. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons); †P < 0.05, †††P < 0.001 compared to wild-type mice fed the same diet (Student’s t test). n.d., not detected.

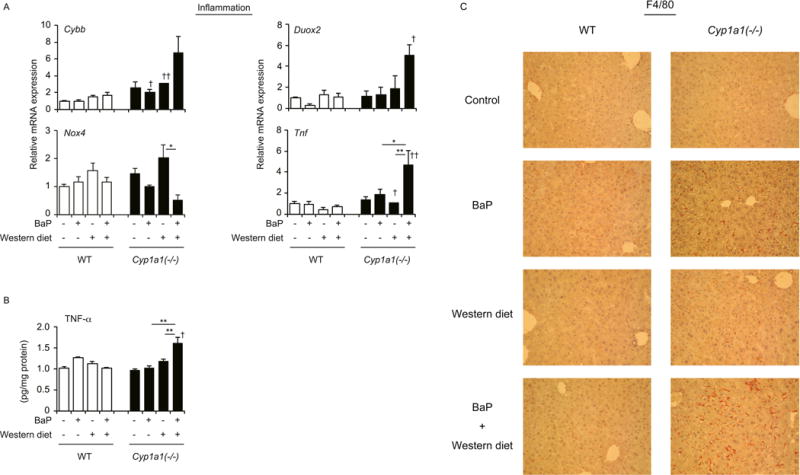

3.5. Effect of combined Western diet plus oral BaP treatment on liver inflammation

The combination of a Western diet and oral BaP increased mRNA levels of Cybb (a subunit of the NOX2 complex), Duox2 and Tnf and protein levels of TNF-α in liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) but not wild-type mice (Fig. 5, A and B). By contrast, Nox4 expression was decreased in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice receiving the combined treatment, compared with those fed the Western diet without BaP (Fig. 5A). BaP treatment induced appearance of F4/80-positive cells in liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice, and the combined Western diet plus BaP further increased F4/80-positive cells in these mice (Fig. 5C). These findings were not observed in wild-type mice. Thus, the combination of a Western diet and BaP induces an inflammatory response, in addition to lipid accumulation, in liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice.

Fig. 5.

Combined treatment with the Western diet plus BaP induces hepatic inflammation in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice. (A) mRNA levels of NOX2 (Cybb), Nox4, Duox2 and Tnf. (B) Hepatic levels of TNF-α protein. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons); †P < 0.05, ††P < 0.01 compared to wild-type mice fed the same diet (Student’s t test). (C) Immunostaining of liver with anti-F4/80 antibody. Wild-type (WT) and Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed the control diet versus Western diet, with or without BaP, for 3 weeks.

4. Discussion

In this study, we show that oral BaP induces liver dysfunction in in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet, which exacerbates hepatic steatosis and inflammation while these effects are not seen in wild-type mice. We provide experimental evidence supporting involvement of the BaP-containing Western diet in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. Our results therefore demonstrate a protective role of CYP1A1 against NAFLD development.

More than a decade of oral BaP studies have made it clear that BaP-induced toxicity or cancer is dependent on the dose of BaP, acute versus chronic dosage as a function of time, route-of-administration, organs targeted, and genetic background of the animal (Nebert et al., 2013). Oral BaP detoxication has been shown to be mediated by CYP1A1 located in the proximal small intestine rather than hepatic CYP1A1 (Shi et al., 2010). The current results in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice demonstrate the protective role of CYP1A1 against NAFLD induced by a Western diet with BaP. Therefore, lack of hepatic and gastrointestinal CYP1A1 in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed the Western diet plus oral BaP is suggested to result in NAFLD.

The findings in this study present a number of lines of supporting evidence. Cyp1a1(−/−) but not wild-type mice receiving the Western diet plus BaP show increased hepatic cholesterol, triglyceride and bile acid levels. Disturbance of bile acid homeostasis is associated with NAFLD (Chow et al., 2017). Increased hepatic expression of the bile acid export transporters Abcc4 and Slc51b, combined with decreased mRNA levels of bile acid import transporters Slc10a1, Slco1a1 and Slco1b2, as well as bile-acid-synthesizing enzymes Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1 (Figs. 2 and 3) were all observed in Cyp1a1(−/−) but not wild-type mice receiving the Western diet plus BaP. The combined treatment also increased MRP4 protein levels and decreased OATP1A1 protein levels in the liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 2). These changes can protect hepatocytes from bile acid toxicity and may lead to increased bile acid levels in the circulation. In contrast, hepatic Abcc3 and Slc51a mRNA levels were diminished in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet with BaP, compared to these mice treated with Western diet alone, or BaP alone (Fig. 2). In hepatocytes, the farnesoid-X receptor (FXR) and pregnane-X receptor (PXR) are able to sense excessive amounts of bile acids and regulate bile acid transport and synthesis (Chiang, 2009; Makishima et al., 1999; Staudinger et al., 2001; Xie et al., 2001). FXR suppresses bile acid import and synthesis by inhibiting expression of Slc10a1, Cyp7a1 and Cyp8b1, and enhances bile acid export by inducing expression of Abcb11, Slc51a and Slc51b, whereas PXR induces bile acid export through Abcc3 and Abcc4 expression (Lefebvre et al., 2009). In mice receiving oral BaP, induction of Abcb11, Abcc3 and Slc51a expression is ineffective and fails to protect against bile acid toxicity. Dysregulated expression of these genes may cause increased bile acid levels in the liver. Furthermore, inflammation and oxidative stress in the liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 5) is likely to influence bile acid transport and metabolism (Aitken et al., 2006).

The Western diet also increased expression of cholesterol export transporter genes Abcg5 and Abcg8, as well as lipogenic genes Srebf1, Scd and Acc (Figs. 2 and 3). The Western diet used in our experiments contained high cholesterol levels, which activate the oxysterol receptor liver-X receptor (LXR), which in turn up-regulates expression of these genes (Peet et al., 1998; Tontonoz and Mangelsdorf, 2003). While increased ABCG5 and ABCG8 transporters can protect hepatocytes from cholesterol accumulation, induction of these lipogenic genes may enhance hepatic steatosis, which has been reported in mice treated with synthetic LXR ligand (Chisholm et al., 2003; Schultz et al., 2000). However, Srebf1, Scd and Acc mRNA levels in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice were similar to, or only slightly higher than, those in wild-type mice (Fig. 3), and the marked steatosis in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet plus BaP cannot be explained by these gene expression changes. Interestingly, Lpl mRNA levels were drastically elevated in Cyp1a1(−/−), compared to wild-type mice, fed the combined treatment (Fig. 3). Up-regulation of the Lpl gene is known to be elicited by LXR activation and AHR activation in the liver of mice (Angrish et al., 2012; Minami et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2001), and hepatic LPL over-expression causes fatty liver (Kim et al., 2001). These findings suggest that the combined treatment with a Western diet plus BaP induces hepatic steatosis by activating AHR and LXR signaling, resulting in Lpl induction in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice. Unexpectedly, the combined treatment decreased LPL protein levels in the liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice (Fig. 3). A potent AHR activator, 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin, suppresses LPL activity in 3T1-L1 murine preadipocytes (Olsen et al., 1998). The discrepancy between mRNA and protein expression changes of LPL may due to cellular dysfunction induced by BaP toxicity, such as enhanced oxidative stress, or differential effects of AHR activation. Further studies are needed to elucidate mechanisms of dysregulation of genes involved in transport and metabolism of bile acids and lipids in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed the Western diet with BaP.

Treatment with BaP alone increased and combined treatment with a Western diet and BaP decreased plasma triglycerides levels in wild-type mice, while these treatments did not change hepatic triglyceride levels (Fig. 1). Treatment with 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin induces hypertriglyceridemia in rats in a strain-dependent manner (Walden and Schiller, 1985), and also in rabbits through suppression of adipose tissue LPL (Brewster et al., 1988). BaP may increase plasma triglyceride levels by affecting extrahepatic tissues. The combined treatment with a Western diet and BaP also decreased plasma triglyceride levels, but increased hepatic triglyceride levels. Activation of the bile acid receptor FXR suppresses very low density lipoprotein secretion (Hirokane et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2016). Bile acid accumulation may contribute to decreased plasma triglyceride levels in mice treated with a Western diet plus BaP. Hepatic inflammation and oxidative stress induced by BaP metabolic activation may also influence dysregulation of lipid metabolism.

In the liver of Cyp1a1(−/−) mice, BaP treatment induced the expression of Cyp1a2 and Cyp1b1 (Fig. 4), as reported previously (Uno et al., 2006). The combined treatment with a Western diet and BaP decreased expression of Cyp1a2, but not Cyp1b1 (Fig. 4). Because CYP1A1 opposes and CYP1B1 promotes BaP toxicity (Endo et al., 2008; Uno et al., 2006), the combined treatment with a Western diet and BaP is likely to decrease BaP detoxification and enhance metabolic activation. Although expression of other genes involved in BaP metabolism (Gsta1 and Nqo1) was increased, hepatic mRNA levels of the inflammation-associated genes Cybb, Duox2 and Tnf and hepatic TNF-α protein levels were elevated in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed the Western diet with BaP (Figs. 4 and 5). Furthermore, F4/80-positive cells accumulated in the liver of these mice (Fig. 5), indicating inflammation that is associated with Kupffer cell activation. These findings suggest that enhanced BaP metabolic activation, due to the absence of CYP1A1 and the presence of other enzymes such as CYP1B1, induces ROS production and inflammatory responses in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice receiving the combined treatment. The combined treatment with a Western diet and BaP for 3 weeks induced liver injury in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice, but these mice had ameliorated liver damage with showing NAFLD and dysregulated lipid metabolism after the 15-week treatment (Fig. 1). Further studies are needed to elucidate time-dependent changes in NAFLD pathogenesis.

Induction of CYP1A1 by AHR activation had been considered to be required for BaP-induced toxicity, because the original studies using mutant Hepa-1 cells demonstrated that BaP-elicited toxicity is diminished in cells lacking a functional CYP1A1 or AHR (Hankinson et al., 1991). Moreover, Ahr-knockout mice are resistant to BaP-induced carcinogenicity in the skin, and these mice showed no enhanced Cyp1a1 gene expression in skin or liver after subcutaneous BaP injection (Shimizu et al., 2000). Induction of exogenous CYP1A1 expression in CYP1A1-deficient cells restores the formation of BaP-DNA adducts (Maier et al., 2002). On the other hand, overexpression of CYP1A1, as well as CYP1A2, decreases BaP-DNA adduct formation (Endo et al., 2008). The role of CYP1A1 in the intestine-liver axis and the effect on NAFLD pathogenesis warrant further investigation. In conclusion, a Western diet containing BaP, found in grilled meat, increases the risk of NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and CYP1A1 plays a protective role against NAFLD.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Fig. 1. Hepatic and plasma bile acid levels in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet and BaP for 3 weeks. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons); † P <0.05, †† P <0.01 compared to wild-type mice fed the same diet (Student’s t-test).

Supplementary Fig. 2. Coomassie blue staining of membranes used for Western blotting of MRP4, OATP1A1 and LPL in Fig. 2D and Fig. 3C. Plasma membrane proteins (20 g/lane) were electrophoresed on a SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblotting. The nitrocellulose membranes were stained with Coomassie blue. M, marker.

Highlight.

A Western diet with benzo[a]pyrene induces hepatic steatosis in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice. Hepatic steatosis in these mice is associated with lipid and bile acid accumulation. Bile acid export and lipid metabolism gene expression is dysregulated in these mice. These mice also have hepatic inflammation, likely due to enhanced benzo[a]pyrene toxicity.

CYP1A1 protects against nonalcoholic fatty liver disease induced by benzo[a]pyrene.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of Makishima lab for technical assistance and helpful comments and Dr. Andrew I. Shulman for editorial assistance.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP 21590319 (to S.U.), and NIH Grants R01 ES014403 and P30 ES06096 (to D.W.N.).

Abbreviations

- BaP

benzo[a]pyrene

- AHR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- CYP

cytochrome P450

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- NQO1, NAD(P)H

quinone oxidoreductase-1

- GSTA1

glutathione S-transferase-A1

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- BSEP

bile salt export pump

- MRP

multidrug resistance associated protein

- OST

organic solute transporter

- NTCP

Na+/taurocholate-cotransporting polypeptide

- OATP

organic anion-transporting polypeptide

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- ABC

ATP-binding cassette

- SREBP-1c

sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c

- SCD

stearoyl-CoA desaturase

- ACC

acetyl-CoA carboxylase

- LPL

lipoprotein lipase

- CYBB

cytochrome b-245, beta polypeptide

- NOX

NADPH oxidase

- DUOX2

dual oxidase 2

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- PXR

pregnane X receptor

- LXR

liver X receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aitken AE, Richardson TA, Morgan ET. Regulation of drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters in inflammation. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2006;46:123–149. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anastasio A, Mercogliano R, Vollano L, Pepe T, Cortesi ML. Levels of benzo[a]pyrene (BaP) in “mozzarella di bufala campana” cheese smoked according to different procedures. J Agric Food Chem. 2004;52:4452–4455. doi: 10.1021/jf049566n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angrish MM, Mets BD, Jones AD, Zacharewski TR. Dietary fat is a lipid source in 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD)-elicited hepatic steatosis in C57BL/6 mice. Toxicol Sci. 2012;128:377–386. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aygun SF, Kabadayi F. Determination of benzo[a]pyrene in charcoal grilled meat samples by HPLC with fluorescence detection. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2005;56:581–585. doi: 10.1080/09637480500465436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster DW, Bombick DW, Matsumura F. Rabbit serum hypertriglyceridemia after administration of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD). J. Toxicol. Environ. Health. 1988;25:495–507. doi: 10.1080/15287398809531227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang JY. Bile acids: regulation of synthesis. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1955–1966. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900010-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm JW, Hong J, Mills SA, Lawn RM. The LXR ligand T0901317 induces severe lipogenesis in the db/db diabetic mouse. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:2039–2048. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300135-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow MD, Lee YH, Guo GL. The role of bile acids in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Mol Aspects Med. 2017;56:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conney AH. Induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes: a path to the discovery of multiple cytochromes P450. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2003;43:1–30. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.43.100901.135754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton TP, Dieter MZ, Matlib RS, Childs NL, Shertzer HG, Genter MB, Nebert DW. Targeted knockout of Cyp1a1 gene does not alter hepatic constitutive expression of other genes in the mouse [Ah] battery. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;267:184–189. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo K, Uno S, Seki T, Ariga T, Kusumi Y, Mitsumata M, Yamada S, Makishima M. Inhibition of aryl hydrocarbon receptor transactivation and DNA adduct formation by CYP1 isoform-selective metabolic deactivation of benzo[a]pyrene. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;230:135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamabe A, Uto H, Imamura Y, Kusano K, Mawatari S, Kumagai K, Kure T, Tamai T, Moriuchi A, Sakiyama T, Oketani M, Ido A, Tsubouchi H. Impact of cigarette smoking on onset of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease over a 10-year period. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:769–778. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0376-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankinson O, Brooks BA, Weir-Brown KI, Hoffman EC, Johnson BS, Nanthur J, Reyes H, Watson AJ. Genetic and molecular analysis of the Ah receptor and of Cyp1a1 gene expression. Biochimie. 1991;73:61–66. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(91)90075-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirokane H, Nakahara M, Tachibana S, Shimizu M, Sato R. Bile acid reduces the secretion of very low density lipoprotein by repressing microsomal triglyceride transfer protein gene expression mediated by hepatocyte nuclear factor-4. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45685–45692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M404255200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JK, Fillmore JJ, Chen Y, Yu C, Moore IK, Pypaert M, Lutz EP, Kako Y, Velez-Carrasco W, Goldberg IJ, Breslow JL, Shulman GI. Tissue-specific overexpression of lipoprotein lipase causes tissue-specific insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7522–7527. doi: 10.1073/pnas.121164498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BM, Shim GA. Dietary exposure estimation of benzo[a]pyrene and cancer risk assessment. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2007;70:1391–1394. doi: 10.1080/15287390701434182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JH, Wada T, Febbraio M, He J, Matsubara T, Lee MJ, Gonzalez FJ, Xie W. A novel role for the dioxin receptor in fatty acid metabolism and hepatic steatosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:653–663. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre P, Cariou B, Lien F, Kuipers F, Staels B. Role of bile acids and bile acid receptors in metabolic regulation. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:147–191. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00010.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Yang M, Fu X, Liu R, Sun C, Pan H, Wong CW, Guan M. Activation of farnesoid X receptor promotes triglycerides lowering by suppressing phospholipase A2 G12B expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2016;436:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2016.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier A, Schumann BL, Chang X, Talaska G, Puga A. Arsenic co-exposure potentiates benzo[a]pyrene genotoxicity. Mutat Res. 2002;517:101–111. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(02)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makishima M, Okamoto AY, Repa JJ, Tu H, Learned RM, Luk A, Hull MV, Lustig KD, Mangelsdorf DJ, Shan B. Identification of a nuclear receptor for bile acids. Science. 1999;284:1362–1365. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miele L, Dall’armi V, Cefalo C, Nedovic B, Arzani D, Amore R, Rapaccini G, Gasbarrini A, Ricciardi W, Grieco A, Boccia S. A case-control study on the effect of metabolic gene polymorphisms, nutrition, and their interaction on the risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Genes Nutr. 2014;9:383. doi: 10.1007/s12263-013-0383-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KP, Ramos KS. Impact of cellular metabolism on the biological effects of benzo[a]pyrene and related hydrocarbons. Drug Metab Rev. 2001;33:1–35. doi: 10.1081/dmr-100000138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami K, Nakajima M, Fujiki Y, Katoh M, Gonzalez FJ, Yokoi T. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 and lipoprotein lipase by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. J Toxicol Sci. 2008;33:405–413. doi: 10.2131/jts.33.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura Y, Chiba T, Tomita I, Koizumi H, Miura S, Umegaki K, Hara Y, Ikeda M, Tomita T. Tea catechins prevent the development of atherosclerosis in apoprotein E-deficient mice. J Nutr. 2001;131:27–32. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR): “pioneer member” of the basic-helix/loop/helix per-Arnt-sim (bHLH/PAS) family of “sensors” of foreign and endogenous signals. Prog Lipid Res. 2017;67:38–57. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2017.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Roe AL, Dieter MZ, Solis WA, Yang Y, Dalton TP. Role of the aromatic hydrocarbon receptor and [Ah] gene battery in the oxidative stress response, cell cycle control, and apoptosis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;59:65–85. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00310-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebert DW, Shi Z, Galvez-Peralta M, Uno S, Dragin N. Oral benzo[a]pyrene: understanding pharmacokinetics, detoxication and consequences−Cyp1 knockout mouse lines as a paradigm. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;84:304–313. doi: 10.1124/mol.113.086637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida S, Ozeki J, Makishima M. Modulation of bile acid metabolism by 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 administration in mice. Drug Metab Dispos. 2009;37:2037–2044. doi: 10.1124/dmd.109.027334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura M, Nishida S, Ishizawa M, Sakurai K, Shimizu M, Matsuo S, Amano S, Uno S, Makishima M. Vitamin D3 modulates the expression of bile acid regulatory genes and represses inflammation in bile duct-ligated mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:564–570. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen H, Enan E, Matsumura F. 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin mechanism of action to reduce lipoprotein lipase activity in the 3T3-L1 preadipocyte cell line. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 1998;12:29–39. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0461(1998)12:1<29::aid-jbt5>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peet DJ, Turley SD, Ma W, Janowski BA, Lobaccaro JM, Hammer RE, Mangelsdorf DJ. Cholesterol and bile acid metabolism are impaired in mice lacking the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXRα. Cell. 1998;93:693–704. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81432-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz JR, Tu H, Luk A, Repa JJ, Medina JC, Li L, Schwendner S, Wang S, Thoolen M, Mangelsdorf DJ, Lustig KD, Shan B. Role of LXRs in control of lipogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2831–2838. doi: 10.1101/gad.850400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Z, Dragin N, Galvez-Peralta M, Jorge-Nebert LF, Miller ML, Wang B, Nebert DW. Organ-specific roles of CYP1A1 during detoxication of dietary benzo[a]pyrene. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:46–57. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.063438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T. Xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes involved in activation and detoxification of carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2006;21:257–276. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.21.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimada T, Fujii-Kuriyama Y. Metabolic activation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to carcinogens by cytochromes P450 1A1 and 1B1. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03162.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, Nakatsuru Y, Ichinose M, Takahashi Y, Kume H, Mimura J, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Ishikawa T. Benzo[a]pyrene carcinogenicity is lost in mice lacking the aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:779–782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudinger JL, Goodwin B, Jones SA, Hawkins-Brown D, MacKenzie KI, LaTour A, Liu Y, Klaassen CD, Brown KK, Reinhard J, Willson TM, Koller BH, Kliewer SA. The nuclear receptor PXR is a lithocholic acid sensor that protects against liver toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3369–3374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051551698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tontonoz P, Mangelsdorf DJ. Liver X receptor signaling pathways in cardiovascular disease. Mol Endocrinol. 2003;17:985–993. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uno S, Dalton TP, Derkenne S, Curran CP, Miller ML, Shertzer HG, Nebert DW. Oral exposure to benzo[a]pyrene in the mouse: detoxication by inducible cytochrome P450 is more important than metabolic activation. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:1225–1237. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uno S, Dalton TP, Dragin N, Curran CP, Derkenne S, Miller ML, Shertzer HG, Gonzalez FJ, Nebert DW. Oral benzo[a]pyrene in Cyp1 knockout mouse lines: CYP1A1 important in detoxication, CYP1B1 metabolism required for immune damage independent of total-body burden and clearance rate. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;69:1103–1114. doi: 10.1124/mol.105.021501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uno S, Makishima M. Benzo[a]pyrene toxicity and inflammatory disease. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2009;5:266–271. [Google Scholar]

- Uno S, Sakurai K, Nebert DW, Makishima M. Protective role of cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) against benzo[a]pyrene-induced toxicity in mouse aorta. Toxicology. 2014;316:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walden R, Schiller CM. Comparative toxicity of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD) in four (sub)strains of adult male rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1985;77:490–495. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(85)90189-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie W, Radominska-Pandya A, Shi Y, Simon CM, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Waxman DJ, Evans RM. An essential role for nuclear receptors SXR/PXR in detoxification of cholestatic bile acids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:3375–3380. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051014398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasutake K, Kohjima M, Kotoh K, Nakashima M, Nakamuta M, Enjoji M. Dietary habits and behaviors associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:1756–1767. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i7.1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L, York J, von Bergmann K, Lutjohann D, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Stimulation of cholesterol excretion by the liver X receptor agonist requires ATP-binding cassette transporters G5 and G8. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15565–15570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301311200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelber-Sagi S, Ratziu V, Oren R. Nutrition and physical activity in NAFLD: an overview of the epidemiological evidence. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3377–3389. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i29.3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Repa JJ, Gauthier K, Mangelsdorf DJ. Regulation of lipoprotein lipase by the oxysterol receptors, LXRα and LXRβ. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:43018–43024. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107823200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zollner G, Marschall HU, Wagner M, Trauner M. Role of nuclear receptors in the adaptive response to bile acids and cholestasis: pathogenetic and therapeutic considerations. Mol Pharm. 2006;3:231–251. doi: 10.1021/mp060010s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Fig. 1. Hepatic and plasma bile acid levels in Cyp1a1(−/−) mice fed a Western diet and BaP for 3 weeks. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons); † P <0.05, †† P <0.01 compared to wild-type mice fed the same diet (Student’s t-test).

Supplementary Fig. 2. Coomassie blue staining of membranes used for Western blotting of MRP4, OATP1A1 and LPL in Fig. 2D and Fig. 3C. Plasma membrane proteins (20 g/lane) were electrophoresed on a SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane for immunoblotting. The nitrocellulose membranes were stained with Coomassie blue. M, marker.