Abstract

Physical and mental health is known to have wide influence over most aspects of social life—be it schooling and employment or marriage and broader social engagement—but has received limited attention in explaining different forms of political participation. We analyze a unique dataset with a rich array of objective measures of cognitive and physical well-being and two objective measures of political participation, voting and contributing money to campaigns and parties. For voting, each aspect of health has a powerful effect on par with traditional predictors of participation such as education. In contrast, health has little to no effect on making campaign contributions. We recommend additional attention to the multifaceted affects of health on different forms of political participation.

Keywords: Health, voter turnout, campaign contribution

Although widely studied in other disciplines, political science has scarcely acknowledged the power of health to influence key behavioral outcomes. This inattention is notable both given the evidence regarding the health and cognitive declines older adults face, and because of the evidence regarding how health influences participation in every other major social institution ranging from education (Haas and Fosse 2008; Fletcher 2008) to work (Pelkowski and Berger 2004; Fletcher 2014) to family life (Teachman 2010).

While recent research has begun to examine the relationship between health and political participation, this research is limited by a lack of data on a number of respects, which has likely led to an underestimation of the magnitude of the influence of health on political participation. To remedy these shortcomings, we draw upon the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS), a large survey of older Americans that includes a rich array of objective measures of mental and physical well-being, as well as objective measures of different forms of political participation. The unique quality of the data allows us to make a number of contributions in demonstrating the link between health and political participation. First, we can examine three types of health – cognitive functioning, physical functioning, and overall health functioning – using well-developed metrics to capture these concepts. This improves upon studies that rely upon cruder self-reports of general health. Second, we use objective measures of different forms of political participation: voter turnout and campaign donations. This mix of data is an improvement on the standard approach of relying on self-reports. Finally, our dataset also includes siblings, allowing us to use family fixed effects models to control for background environments that may confound the relationship between health and participation, as well as a rich array of covariates to serve as additional controls. To our knowledge no other study combines these qualities.

We offer evidence that voting is strongly affected by cognitive functioning, general health functioning, and physical functioning. The health effects we estimate are of a similar magnitude to the effects of education, which has long thought to be a potent predictor of voter turnout. Various measures of health have little to no impact on campaign contributions, even when controlling for financial resources. Our results thus challenge the standard view that voting is an “easier” activity than other forms of participation, especially when one takes into account physical health limitations that introduce a barrier to the physical act of voting. We conclude with a call for more serious consideration of health as a contributor to political activity and a reconceptualization of the difficulty of various political acts.

Health and Political Participation

Does health influence political participation? The link between the two is often overlooked, sometimes assumed, and poorly documented. One major analysis of political participation contended that declines in voting later in life are “probably attributable to declining health and increasing disability” but failed to measure any health variables (Strate et al. 1989, 454). A recent book-length treatment of political activism by older adults demonstrates the importance of resources but includes no measures of health as a resource (Campbell 2003). The classic book on turnout – Wolfinger and Rosenstone’s Who Votes? (1980) – makes only one reference to health, incidentally quoting a passage from Milbrath and Goel (1977) pointing out that “good health” must be an intervening variable that connects age to participation. Verba, Schlozman, and Brady’s (1995) sweeping treatment of participation ignores health a factor that might influence the role of resources, engagement, and recruitment to be active in civic life. This is surprising because the three elements of the Civic Volunteerism Model (CVM) readily suggest the ways in which health should influence participation. For example, to the extent that health affects the short-term capacity to engage in tasks, it shapes the ability and skills to participate in politics. If illness and disability concerns compete with public affairs for a person’s attention, health affects personal engagement. And to the extent that health contributes to participation in other social institutions such as the workplace and church, it affects the likelihood of being recruited in political action by others.

Outside of political science, a body of research, especially focused on older adults, demonstrates that different aspects of health – both cognitive and physical – influences people’s ability to function independently. Poor health limits individual’s capacity to perform basic life tasks such as shopping, cleaning, handling one’s finances, managing one’s medications, and preparing food (Barberger-Gateau et al. 1992; Pérès et al. 2008).

Cognitive functioning has the largest influence on individuals’ ability to function independently (Agree et al. 2005; Rockwood et al. 2002; Tatemichi 1994). Those with lower levels of cognitive functioning are substantially less likely to be able to drive and manage their household or finances (Bell-McGinty et al. 2002; Grisby et al. 1998; Royall et al. 2004). Indeed, mismanagement of finances is one of the earliest signs of cognitive decline (Widera et al. 2011). Specific to political participation, we expect that cognitive declines would negatively influence individuals’ ability to process information related to elections – the substantive information about the candidates and issues as well as important procedural details about how to register to vote and cast a ballot, whether by mail or in person. The complexities of making a campaign contribution could also make donating less likely when cognitive health declines, although writing a check or providing a credit card number may be less taxing and more familiar than voting because it mimics other daily activities such as paying bills.

Physical functioning should also influence participation in politics as an extension of how it affects daily tasks. The speed with which a person can walk a short distance has been shown to be a powerful indicator of broader physical functioning (Judge et al. 1996) as well as a strong predictor of future morbidity and mortality, including the propensity to fall, experience bone fractures, be hospitalized, or need a caregiver (Montero-Odasso et al. 2005). At a basic level, this measure captures mobility even beyond walking. Those with lower physical functioning are less likely to drive and have more difficulty navigating public transport systems due to their physical frailty. They are more concerned about leaving the house—to vote for example—on days with poor weather, even rain, because they are more susceptible to falls (Clarke et al. 2015). However, there is little ex ante reason to expect that those with physical frailties are less likely to engage in political activities like contributing to campaigns. Being able to write out a check or provide a credit card number to a fundraiser on the phone requires little physical capacity. Voting, however, may require more physical and cognitive functioning than is commonly recognized.

Only recently have researchers begun to identify health effects on participation. Initial evidence suggests that health is strongly related to engagement with democratic processes. However, this research depends largely on cross-sectional models featuring self-reports of both overall health and voting, often from non-U.S. settings where the nature of mass participation can be quite different due to less burdensome registration laws and the limited relevance of individual donations to campaigns. Nonetheless, this new work provides important groundwork to validate the potential importance of health to help explain variation in political participation. Self-reported overall health is associated with higher self-reported voting in cross-national studies (Goerres 2007; Mattila et al. 2013; Söderlund and Rapeli 2015) and in the U.S. at the aggregate (Blakely, Kennedy, and Kawachi 2001) and individual levels (Pacheco and Fletcher 2015). One study found that more days in the hospital correlated with decreased turnout in Danish elections (Bhatti and Hansen 2012), while those with physical disabilities register and vote less (Clarke et al., 2011; Schur, Kruse, and Blanck 2013). Beyond voting, surveys also reveal that people with disabilities are often less likely to contact public officials, contribute money to campaigns, and attend political meetings, a disparity that grows with age (Schur, Kruse, and Blanck 2013).1 Other research indicates that childhood IQ and cognitive ability are positively related to voting in Britain (Deary, Batty, and Gale 2008)

Despite this small but growing body of evidence, a recent review declared the “potential of health-related explanatory variables has… remained largely unexplored” (Mattila et al. 2013, 886). The limits facing existing research are many. This research has relied almost exclusively on self-reports of overall health, failing to consider the role of more specific aspects of physical health, such as functional limitations and chronic conditions, and largely neglecting the role of cognitive functioning. It has also failed to utilize longitudinal data, or focus specifically on older adults where health would likely have the most obvious impact. We are able to remedy nearly all of these shortcomings. Ours is the first study with objective measures of both the dependent variables and independent variables. In addition to being more valid and reliable, the measures are also more specific, capturing different forms of participation and different aspects of health. By including data on siblings and measures of intelligence from adolescence, we are able to control for genetic and environmental factors that might result in a spurious relationship between health and participation. Moreover, our data are drawn from a large survey of older Americans, the subpopulation whose participation is believed to be most adversely affected by health.

Scholars have recognized that different forms of political participation also have different levels of prevalence in the electorate, suggesting that “the percentage of citizens who engage in a particular political activity is a measure of how hard or easy that act is” (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba 2001). The assumption that more frequently utilized political activities are easier is understandable but misleading when it comes to health. Campaign contributions require money but little in the way or time or skills (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). This suggests that although contributing is far less common than voting, its lesser prevalence does not indicate “difficulty” of the act as much as different set of resources. By contrast, the greater prevalence of voting makes it easy to overlook the wider array of skills and capacities it requires.

The presumption that voting is easier than contributing and other forms of participation might generally be true for the healthy, but not for the millions of people with health problems, illness, or disability. Even with the expansion of early and absentee voting, casting a ballot nonetheless requires skills, initiative, and time. It is also entails several distinct actions, none of which is necessarily familiar. A person must first become registered, a process that requires documentation and some clerical skill. Registration will necessarily not be a hurdle for people who registered long ago, but it can be burdensome for those who must update their address or reregister after allowing the registration to lapse. To vote in person they must then travel to a polling place on a specific days or days to vote. A person who prefers to vote absentee, perhaps because of health limitations, must usually undertake a third step: requesting the absentee ballot in advance of the election. This step also normally entails completion of a form and meeting deadlines. After receiving and completing the ballot, it must have postage affixed to return by mail or delivered by hand to a government office.2

In contrast to the entrepreneurism required to vote, campaign donations require little of individuals. Voting requires initiative on the part of the would-be voter while contributions are actively solicited by private actors. While voting is a multi-step process where failure at any stage prevents participation, contributing is a single act where donors are offered multiple opportunities to engage by different means. Candidates and political parties repeatedly initiate contact with potential donors over the course of the campaign, making it easy to contribute by phone, by mail, in person, or online using a credit card or check. In short, the fundraisers have designed their solicitations to make contributing easy, typically involving just one compact transaction that is analogous to everyday purchases and donations. Indeed, it is an irony of mass politics that, contingent on resources, giving money is less burdensome than voting. Voting is more common because there are stronger norms about the responsibility to vote and because financial resources are not a major consideration. The relative difficulty of voting thus portends a greater role for both cognitive and physical health to be a facilitator or roadblock to participation.

Identifying Effects of Specific Health Factors

Part of the inattention to the relationship between health and participation can be attributed to the absence of appropriate data. The dominant datasets used to examine political participation, such as the ANES and the Youth-Parent Socialization Panel Study contain virtually no health information. Similarly, datasets with useful health data on older adults such as the Health and Retirement Study have no items on political engagement. Even datasets that include both political participation and health measures, such as the General Social Survey or the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Add Health), often have restricted health items. Further, Add Health has no data on older adults, when health might well be most consequential. Even studies that focus on the decline in turnout among the elderly include little in the way of health, with one analysis capturing only hospital stays (Bhatti and Hansen 2012), which are disruptive in a different way than chronic health concerns.

We examine three aspects of health. First, cognitive functioning is based on a standard and detailed test. We control for early life IQ in the models so that cognitive scores are not a simple measure of intelligence, but instead tell us something about how individuals have maintained or lost cognitive resources over the life-course. In short, we are comparing individuals who had the same IQ scores as adolescents, but vary in their cognitive capacity in later life. Our measures capture the kinds of cognitive capacities more likely to decline in later life and which impact different aspects of well-being and behavior (Comijs et al. 2004; Njegovan et al 2001). Second, physical health functioning is measured via a timed walking speed test. Although it might seem overly specific and distant from political activity, gait speed has been shown to be a reliable indicator of hospitalization (Cesari et al. 2005) and mortality (Studentski et al. 2011) among older adults. Indeed, gait speed is considered the most valid and reliable measures of all around physical functioning among older adults currently available (van Kan et al. 2009). Finally, we also employ a general measure of health functioning called a Health Utilities Index® (HUI) captures vision, hearing, speech, ambulation, dexterity, emotion, and pain levels. More measurement details are included in the data section (Feeny et al. 2002)..

We offer four theoretical and empirical innovations on prior work. First, we have specific, objective health measures rather than self-reported general assessments of a person’s health. No other political survey has valid and reliable measures of this type. Second, rather than rely on self-report for voting or other political engagement activities that are prone to biases due to misremembering and social desirability, we use objective data on voting and campaign contributing from government records. Third, we draw on a large longitudinal dataset that resolves the potential inferential problems that result when health measures are not measured prior to measures of political participation items and when samples lack a sizable number of older adults. Fourth, we account for potential early life family confounders – household environments that both shape health and the propensity to participate such as being taught social values that affect general behavior – by including siblings in the analysis to isolate the effects of health. Adding fixed effects for families into the models provides a strong control for a host of social and demographic factors that might be correlated with health and civic participation.

Data

Our data are drawn from the Wisconsin Longitudinal Survey (WLS), a longitudinal survey of individuals who have been interviewed repeatedly over the course of their lifespans. The WLS is one of the longest running cohort studies with such a large breadth of data. Indeed the National Research Council extols the value of the British birth cohort surveys but adds, “in the United States, the WLS … is the closest to the British birth cohorts in richness of psychosocial information, but goes well beyond the British studies” with its assessments of education, occupation, and sibling data (National Research Council 2001, 105). No other longitudinal study combines the same range of high quality health measures and political participation measures that are featured in the WLS. The original WLS sample was comprised of one-third of Wisconsin high school graduates from the class of 1957 (N = 10,317). Subsequently this sample was expanded to cover a selected sibling, raising the sample size to 18,473. The retention rate of the original 1957 respondents in 2004 was 75 percent, and 86 percent among the non-deceased sample. Ours might be the only study on political participation in old age that employs life course longitudinal data. Most studies rely on either cross sectional data or short panels and measure key variables simultaneously.

Inclusion of siblings is novel and it allows us to estimate more stringent models that help to rule out alternative explanations. After estimating straightforward multivariate models of activity, we add fixed effects for families (i.e., pairs of original respondents and siblings). This technique has only been rarely used in the study civic engagement (Hillygus, Holbein, and Snell 2015; Schnittker and Behram 2012). This allows us to control for common aspects of family background environments that are not captured in conventional survey demographic measures.

Including siblings also expands the age range beyond the original sample of graduates. As we show later, the pooled sample has an age range from 40 to 104. This coverage of older Americans is superior to other political surveys, which have fewer older respondents and often “top code” the older respondents in their 80s or beyond to maintain confidentiality.

Dependent Variables

We examine two forms of activity – voting in elections and donating to political campaigns – that are drawn from external data that we have appended to the WLS. Descriptive statistics on all variables appear in Table A1 of the Appendix.

First, we have merged in recent voting histories from state voter files. These data have been provided by a private firm, Catalist, that collects and cleans such data from state records (see Ansolabehere and Hersh 2014). The high quality of the WLS data allowed for a nearly perfect match with Catalist voting records.3 This provides us with objective measures of voter turnout in the 2008, 2010, and 2012 elections, ranging from 79% in 2010 to 86% in 2008. These high levels are not surprising given that this is a sample of older Americans, a group that votes more than other age groups, and one that is slightly more educated than the rest of the population and disproportionately residing in the upper Midwest, where voter turnout tends to be high.

Second, we incorporate data from the Federal Elections Commission on financial contributions made to candidates running for federal office and to political action committees.4 We code the measure as a dichotomy indicating whether a respondent gave any money to a federal candidate in the 2008, 2010, or 2012 elections.5 Although sacrificing some nuance, this coding puts donating on the same zero-to-one scale as the other activities. The Appendix includes models using alternative coding, such as the number of donations and total amount given.

Independent Variables

We examine three measures of cognitive and physical health. These indicators reflect more aspects of health than do measures in other political surveys and they do so objectively rather than relying on self-reports.

Our first health measure relates to cognitive functioning. In the 2004 and 2011 waves, respondents were asked to undergo a “similarities” module based on the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale in which they explained how two items are alike. In those same waves participants were also administered additional direct tests of cognitive functioning using a “letter” module, which asked respondents to name as many words as they could starting with a specific letter in a 60-second time period and a module where they were asked to mentally rearrange and verbally restate increasingly lengthy sets of one-digit numbers. Respondents were also asked to recall words provided to them both immediately after the words are recited to the study respondents and then later in the later in the interview to tested for delayed recall abilities. Items from these scales tapping memory/attention, abstract reasoning, and verbal fluency are used to estimate a general cognitive functioning factor. This factor was extracted by estimating the structural equation described by (Yonker, Hauser, and Freese 2007), resulting in an approximately normally distributed variable with a mean of zero and standard deviation of one.6

One concern with such a measure is that it reveals intelligence or mental ability, which is relatively fixed, rather than cognitive health, which may decline in older age. To account for this concern, we contextualize the meaning of cognitive functioning by controlling for an early-life measure of IQ. These IQ tests, based on the Henmon-Nelson test of mental ability, were administered to all high school students in Wisconsin in 1957 and collected from state records. Because the intelligence measure is measured decades before the outcomes of interest, its exogeneity to both health and political activity is especially convincing, allowing us to interpret cognitive functioning as decline in cognitive skills from early life.

As a general measure of physical health functioning, we employ the Health Utilities Index. The HUI is a multi-attribute measure designed to classify individual health status. Like the cognitive functioning measures, he HUI measures are available both in 2004 and 2011 and so provide some temporal proximity to the 2008, 2010 and 2012 elections.7 The HUI scale measures different types of health that cumulatively provide a sense of overall health. It includes specific questions about vision, hearing, speech clarity, ambulation, dexterity, sense of emotional well-being, memory, frequency of pain. Although the measure relies upon self-reports of health, it has been shown to correlate strongly with objective measures of health outcomes (Horsman et al. 2003). Indeed, the 2011 wave of the WLS included both the HUI and objective measures and the items correlate strongly with one another and behave in similarly in regression models.

For 2012 political participation activities, we are able to provide a stronger test of physical health with an objective indicator of physical mobility. In 2011, each respondent’s walking speed was measured objectively during the in-person interview. The walking speed course was 2.5 meters. Participants walked it twice using their normal gait. The final measure is an average of the two tests measured in meters per second.

Although we believe that each of these measures is tapping into a distinct aspect of health, they are correlated with one another at magnitudes ranging from .07 to .44.8 The shared variance among the measures makes it less likely that any one of them will have a statistically significant coefficient, so we may be “over-controlling” for health. We view inclusion of all three variables as a conservative test of whether health matters and its various cognitive and physical elements can be distinguished from one another.9

Modeling Strategy

We estimate multivariate models of participation as a function of the health indicators and a series of control variables. In addition to IQ, the control variables are standard demographic predictors in models of mass participation (e.g., Wolfinger and Rosenstone 1980; Verba, Schlozman, and Brady 1995). As is common in studies of voter turnout, we include both age and age-squared. This allows for a nonlinear relationship and the decline of participation that is observed in older age.10 As a measure of financial resources, we include net worth from the WLS, defined in terms of deciles. Whereas most research uses annual household income, that indicator is not as meaningful among the older population in our sample, many of whom are retired and depend more on accumulated assets than the rest of the population. The models include a measure of formal educational achievement because of the skills, resources, and social connections it provides to underwrite the costs of participation. Education is measured continuously as years of schooling, but models that measure education using discrete dummy variables for achievement produce similar results. We control for sex with a dummy variable for men to account for the lower participation levels by women in activities outside of voting (Burns, Schlozman, and Verba 2001). We include measures of parental education and income at the time the subjects were initially interviewed in as teens in 1957. Although those factors have been shown to influence offspring participation, the effect dissipates over time and should have minimal impact on the older population we are studying (Plutzer 2002).11

To complete the model specification, we add dummy variables for the states where the largest numbers of WLS respondents live. This is to account for state-specific factors such as the competitiveness of political campaigns, election laws, political culture, and even climate that might affect participation. It is also possible that relocating is a consequence of health or other factors, which would dampen their apparent influence in the models and render our analysis an even more conservative test.12

For each dependent variable of interest, we estimate two varieties of models. The first is a probit model that includes all of the respondents. We refer to this as the “full sample” model because it includes both the original WLS respondents and their siblings, allowing us to maximize the sample size. The second is a linear regression model run only on pairs of siblings with fixed effects included for each family. It is crucial to note that the dummy variables for pairs of siblings in the dataset essentially net out any common environmental and genetic factors that results from having shared parents and households. Including these fixed effects provides for much stronger evidence of causality, but they also come at a cost. It reduces our sample size substantially because we omit original respondents who lack a sibling (or where a sibling could not be contacted). We must omit measures of parental education and income because they are perfectly correlated with family fixed effects.

Results

Table 1 presents the results of these models for voting in 2008, 2010 and 2012. The demographic control variables show some significant and substantial effects on participation. Age does not have a robust effect on voting but age-squared is generally negative and significant, indicating a decline in turnout in older age that goes beyond health. But it also indicates that age per se is not what results in the rise or fall in turnout over the lifespan. Rather, the physical and mental health factors we have examined are among the mechanisms that translate age into participation levels.13 As might be expected in recent elections, sex differences in voter turnout are minimal, with only modest evidence that men are less likely to vote. Net income is one of the control variables that displays the strong effects seen elsewhere in the literature.

Table 1.

Health and Voting

| 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Full Sample (Probit) |

Sibling Fixed Effects (LPM) |

Full Sample (Probit) |

Sibling Fixed Effects (LPM) |

Full Sample (Probit) |

Sibling Fixed Effects (LPM) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Cognitive Functioning | 0.101*** | 0.029*** | 0.087*** | 0.039*** | 0.204*** | 0.055*** |

| (0.030) | (0.011) | (0.028) | (0.013) | (0.040) | (0.013) | |

| General Health (HUI) | 0.323*** | 0.055* | 0.528*** | 0.107*** | 0.558*** | 0.101*** |

| (0.094) | (0.031) | (0.087) | (0.036) | (0.097) | (0.036) | |

| Physical Health (walking speed) | __ | __ | __ | __ | 0.456*** | 0.038 |

| __ | __ | __ | __ | (0.106) | (0.033) | |

| Walking Speed Missing | __ | __ | __ | __ | 0.315** | 0.032 |

| __ | __ | __ | __ | (0.134) | (0.048) | |

| IQ | 0.003** | −0.00001 | 0.006*** | 0.0014** | 0.001 | −0.00004 |

| (0.002) | (0.0005) | (0.001) | (0.0006) | (0.002) | (0.001) | |

| Age | 0.031 | −0.009 | 0.038 | −.001 | 0.048 | −0.002 |

| (0.026) | (0.006) | (0.024) | (0.007) | (0.032) | (0.008) | |

| Age2 | −0.029** | −0.008*** | −0.048*** | −.013*** | −0.020 | −0.009** |

| (0.013) | (0.003) | (0.012) | (0.004) | (0.016) | (0.004) | |

| Net Worth | 0.055*** | 0.006** | 0.055*** | 0.007*** | 0.040*** | 0.003 |

| (0.007) | (0.002) | (0.007) | (0.003) | (0.009) | (0.003) | |

| Education | 0.018* | −0.002 | 0.035*** | 0.003 | 0.006 | 0.003 |

| (0.010) | (0.003) | (0.009) | (0.003) | (0.012) | (0.004) | |

| Father’s Education | −0.002 | __ | −0.005 | __ | −0.004 | __ |

| (0.007) | __ | (0.006) | __ | (0.008) | __ | |

| Mother’s Education | −0.002 | __ | −0.002 | __ | 0.001 | __ |

| (0.008) | __ | (0.007) | __ | (0.009) | __ | |

| Parental Income | −0.0002 | __ | −0.0002 | __ | −0.0005 | __ |

| (0.0003) | __ | (0.0003) | __ | (0.0004) | __ | |

| Male | −0.040 | −0.012 | 0.014 | 0.010 | 0.032 | 0.018 |

| (0.039) | (0.011) | (0.036) | (0.013) | (0.046) | (0.014) | |

| N | 7,664 | 3,622 | 7,502 | 3,552 | 5,920 | 2,268 |

| Adjusted R2 | __ | 0.024 | __ | 0.025 | __ | 0.027 |

| Log Likelihood | −2,694 | __ | −3,323 | __ | −2,022 | __ |

Note:

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

State dummy variables and a constant are included but are not reported.

Turning to the variables of primary interest, the results suggest that cognitive functioning in later life, controlling for adolescent IQ, has a robust effect on voting across the models. There is also consistent evidence that HUI scores, our measure of general health functioning, are associated with higher rates of voting. One difference for the 2012 model is the addition of the measure of physical health based on walking speed, which shows positive effects in one of the two models. Comparing the “full sample” and sibling fixed effects models, the effects of health are remarkably consistent. To be sure that any differences are due to the inclusion of fixed effects rather than having fewer observations in the sibling models, in Table A2 of the Appendix we report the two sets of models after limiting them to equivalent samples. Doing so does not alter the substantive findings. In short, even when controlling for standard demographic predictors and applying family fixed effects to net out environmental and genetic factors, all three measures of health help explain variation in voter participation.

For one alternative specification of the models we also employed self-reports of voting in 2008 from the WLS.14 The existing literature on health and participation rests on such measures, and so it is instructive to compare with our analysis based on objective indicators. Studies show that voter turnout and explanatory variables have stronger relationships when measured subjectively rather than objectively due to the correlated errors in self-reports (Vavreck 2007). Thus, it would seem that self-reported measures would be biased toward finding relationships rather than toward the null.15 However, we found that cognitive functioning and physical health were not meaningful predictors or self-reported voting. This may be because the self-reports were collected more than two years after the election; a survey conducted more immediately after the vote might yield more consistent results, as long as reporting errors are not correlated with health. Regardless of the reason for the variance in results between subjective and objective indicators, that such variance exists testifies to the value of using objective measures of political behavior.

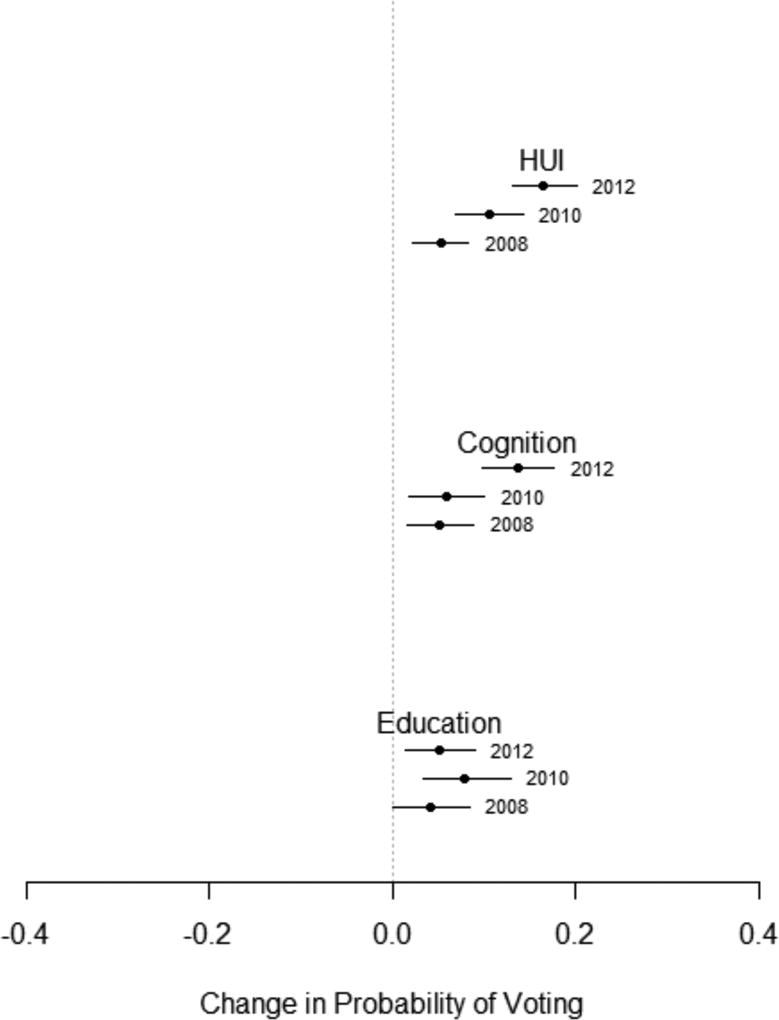

To aid in interpretation of the models, Figure 1 displays the marginal effects of the two main health variables. The figure also includes the effects of education, a heavily-documented correlate of voter turnout, for comparison. The dots in the graph shows how the probability of voting is altered by shifting each variable from its 25th percentile value to its 75th percentile value based on the “full sample” probit models in Table 1. The error bars around each dot show the 95% confidence intervals. The general health measure (HUI) boosts the likelihood of voting by five percentage points in the 2008 election to 15 points in the 2012 election. The impact of cognitive functioning is only slightly smaller in magnitude, with a marginal effect of five percentage points to just above 10 points across the three elections. To put the effects of physical and cognitive health in context, we note that their total effects are generally as big or bigger in magnitude than education, which is only significant in two of the three elections.

Figure 1. Marginal Effects of Health on Voting.

Note: Based on Table 1 probit models for full sample. Each point represents the marginal effects of moving an independent variable from its 25th percentile value to its 75th percentile value. Error bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals.

Table 2 presents evidence on the relationship between health and political contributions. As one would expect, wealth is a robust predictor of campaign contributing, although the effect is about on par with its effect on voting. Education shows an even stronger relationship to political donations than to voting. In contrast with voting, age appears to have little effect on contributing. More so than with voting, parental education predicts political donations, but only for the male parent. Unlike voting, we find no sex differences in contributing. Table A8 in the Appendix shows that these demographic effects largely hold up even when the health variables are omitted from the models.

Table 2.

Health and Contributing

| 2008 | 2010 | 2012 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Full Sample (Probit) |

Sibling Fixed Effects (LPM) |

Full Sample (Probit) |

Sibling Fixed Effects (LPM) |

Full Sample (Probit) |

Sibling Fixed Effects (LPM) |

|

|

|

||||||

| Cognitive Functioning | 0.060* | 0.034*** | 0.029 | 0.021* | 0.023 | 0.003 |

| (0.032) | (0.009) | (0.030) | (0.011) | (0.036) | (0.015) | |

| General Health (HUI) | 0.083 | −0.005 | 0.079 | −.025 | −0.092 | −0.054 |

| (0.116) | (0.027) | (0.109) | (0.030) | (0.099) | (0.040) | |

| Physical Health (walking speed) | __ | __ | __ | __ | 0.106 | 0.009 |

| __ | __ | __ | __ | (0.093) | (0.037) | |

| Walking Speed Missing | __ | __ | __ | __ | −0.071 | 0.047 |

| __ | __ | __ | __ | (0.138) | (0.053) | |

| IQ | 0.004** | −0.0005 | 0.006*** | 0.0002 | 0.008*** | 0.002*** |

| (0.002) | (0.0004) | (0.002) | (0.0005) | (0.002) | (0.001) | |

| Age | 0.052* | 0.012** | 0.015 | −0.002 | 0.009 | 0.003 |

| (0.031) | (0.005) | (0.028) | (0.006) | (0.030) | (0.009) | |

| Age2 | −0.017 | 0.002 | −0.002 | −0.002 | 0.014 | −0.003 |

| (0.017) | (0.003) | (0.015) | (0.003) | (0.015) | (0.004) | |

| Net Worth | 0.050*** | 0.006*** | 0.052*** | 0.009*** | 0.047*** | 0.011*** |

| (0.008) | (0.002) | (0.008) | (0.0002) | (0.008) | (0.003) | |

| Education | 0.047*** | 0.007*** | 0.033*** | 0.009*** | 0.047*** | 0.018*** |

| (0.010) | (0.003) | (0.010) | (0.002) | (0.010) | (0.004) | |

| Father’s Education | 0.020*** | __ | 0.031** | __ | 0.010 | __ |

| (0.007) | __ | (0.012) | __ | (0.007) | __ | |

| Mother’s Education | 0.002 | __ | 0.021 | __ | 0.016* | __ |

| (0.009) | __ | (0.013) | __ | (0.008) | __ | |

| Parental Income | 0.001** | __ | 0.0005* | __ | 0.001* | __ |

| (0.0003) | __ | (0.0003) | __ | (0.0003) | __ | |

| Male | −0.033 | 0.002 | −0.027 | 0.008 | −0.077* | −0.016 |

| (0.042) | (0.010) | (0.040) | (0.011) | (0.042) | (0.016) | |

| N | 7,664 | 3,622 | 7,686 | 3,552 | 5,920 | 2,268 |

| Adjusted R2 | __ | 0.012 | __ | 0.023 | __ | 0.025 |

| Log Likelihood | −2,325 | __ | −2,665 | __ | −2,569 | __ |

Note:

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01.

State dummy variables and a constant are included but are not reported.

The results suggest that cognitive functioning influences whether one participates by donating, but not in a robust fashion. It is a significant factor in three of the six models. Neither physical health nor general health is associated with donations in any model. It seems that cognitive and physical health have only minimal influence on financial contributions to campaigns. To verify these null findings, we undertook several robustness checks. First, as with voting, we reestimated the models after limiting them to the same samples to ensure that the fixed effects rather than sample sizes were responsible for the different findings between the two specifications. The results, which appear in Table A3 of the Appendix, are consistent with the baseline models. Second, we account for the fact that whereas voting is an individual act, contributing is often done on behalf of a couple or household. Fortunately, the WLS asks respondents who “handles the finances” for the household. We reestimated models after limiting the sample to those who reporting handling finances and found similar results. Third, we considered several different ways to measure the dependent variable. Our models operationalize contributing as a dichotomous measure (giving or not) to make it comparable with the voting models. But contributing is different than voting, where a person is allowed to participate only once in an election, in that a person may engage in it several times during a campaign and given varying amounts. This opens the possibility of different operationalizations of the dependent variable that in turn demand different modeling strategies. For example, one might model the number of times a person made contributions using a negative binomial count model. In Table A6 of the Appendix we report several alternative models of contributing in 2008. The results show that cognitive functioning has a moderately consistent effect on contributing, achieving significance in three of the five alternative specifications. As in previous models, this result holds even controlling for IQ in adolescence. In none of the five alternative specifications does our measure of general health become significant.

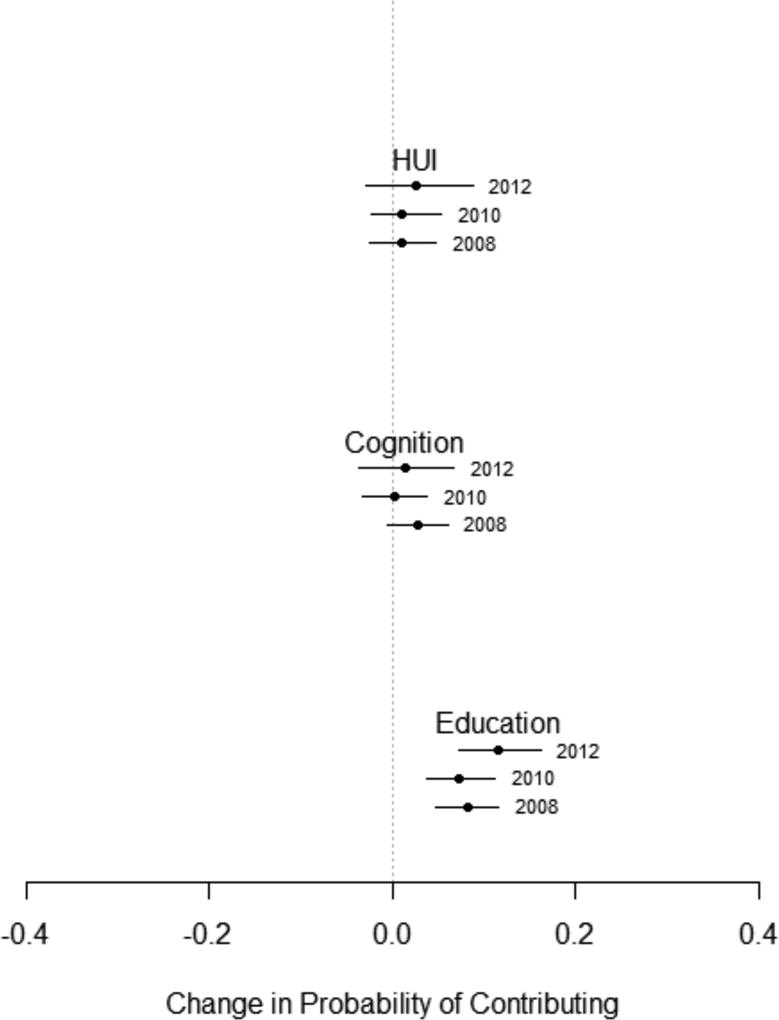

To visualize the effects of health on contributing, Figure 2 shows marginal effects of the health variables. The effect of education is included again for comparison. In sharp contrast with the graph for voting, there is limited evidence for substantively meaningful effects of cognitive health and no evidence that physical health matters. By way of comparison, education has a sizable and consistent effect on contributing, even more so than for voting. When shifted from its 25th percentile to 75th percentile, educational attainment increases the likelihood of contributing by about 10 percentage points. Apparently the resources required to make a financial contributing are rooted in education (and finances) rather than health.

Figure 2. Marginal Effects on Contributing.

Note: Based on Table 2 probit models for full sample. Each point represents the marginal effects of moving an independent variable from its 25th percentile value to its 75th percentile value. Error bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals.

Discussion

As with so many other areas of social life, health has the potential to sharply influence participation in politics. This is especially true in older age when cognitive and physical health becomes a more common concern. Surprisingly, almost no studies of political participation have considered health, even those that emphasize resources, skills, social networks, and motivation as key theoretical mechanisms. This oversight warrants a course correction. Relying on a rich dataset that includes objective measures of both the independent and dependent variables, our analysis provides support for the importance of health, even with the use of demanding models that include sibling fixed effects. We find that the significance of the health items varies with the type of participation, just as it does with other variables. General functioning and physical health both affect the likelihood of voting in a consistent fashion.

When it comes to making financial donations, cognitive functioning shows uneven effects and there is little evidence that general physical health matters. Certain types of resources are more prominent: wealth, education, and parental education. Cognitive functioning appears to matter in ways similar to these other types of resources, even with the inclusion of factors that are correlated with cognitive functioning. In particular, the inclusion of IQ allows us to interpret the cognitive measure as not just one of general cognitive skills, but that of cognitive decline. Net of these factors, cognitive functioning appears to play a significant role in whether people vote and, to a lesser degree, donate money. Up to now, research on health and political participation has focused on general health indicators, or physical restrictions such as disability. This has been a welcome and overdue area of inquiry. At the same time, a clear finding from our work is that this conceptualization of health is too narrow, excluding attention to cognitive resources.

A limitation of our study is that we analyze an older cohort where health might be a more prominent factor. The percentage of Americans reporting fair or poor health is 18% for those between 65 and 74, and 25% for those 75 and older (Blackwell, Lucas, and Clarke 2014). Among those 65 and older a remarkable 50% report some form of disability (Brault 2012). The prevalence of disabilities in the population is likely to grow as population continues to age (Schur, Kruse, and Blanck 2013). While this age cohort may be vulnerable to health problems to a greater degree than younger populations, there are three reasons why our study is important.

First, a growing proportion of the population is aging. Indeed, the Gerontological Society of America and American Society on Aging have each promoted initiatives to understand civic engagement among older populations. When policymakers become aware of the role that health plays in voting, they are better placed to reduce the potential for unequal participation among older citizens in poor health relative to other groups. Such research has mattered in policy changes to reduce the voting gap between the disabled and others. Federal legislation such as the Americans with Disabilities Act and Help America Vote Act aimed to make polling places more accessible for those with disabilities. State-level policy initiatives have also been shown to at least partially remedy the voting gap between people with and without disabilities (Schur, Kruse, and Blanck 2013).

Second, health issues are prevalent throughout the general population, not just older Americans. At the broadest level, recent surveys asking Americans about their “general health” show that more than one in ten adults labels themselves as being only in “fair” or “poor” health. The Census Bureau estimates that approximately 57 million people had a disability in 2010, or about one in five Americans (Brault 2012).16 The 2012 Current Population Survey of non-voters found that 14% attributed their failure to vote to an illness or disability, making this reason about as frequent as being too busy, lacking interest in the campaign, or disliking the candidates.

Third, as one of the first studies of the effects of health, we willingly make a tradeoff between generalizability and causal inference. The richness and reliability of both health and participation measures in the WLS are unique. While another potential limitation is that the WLS sample is drawn from a largely white population in a single state in a particular era, limiting generalizability to other racial groups or political cultures, this is offset by the advantages of the WLS. The sample’s homogeneity reduce the potential for error due to unobserved regional and racial differences, and increase confidence in the internal validity of the models, particularly with the use of sibling fixed effects. In a supplemental analysis appearing in Table A9, we use the Current Population Survey (CPS) from 2008, 2010, and 2012 to analyze whether the general relationship between self-reported health problems and voter turnout holds for respondents who mimic the most distinction elements of the WLS sample: whites over 60 years old who live in Wisconsin.17 We find that while the overall relationship is negative as expected (at about −15 percentage points), the effect is actually smaller among older Wisconsin whites (at about −12 percentage points). This suggests that the results reported in this paper might actually understate the effects of health on participation.

Conclusion

The primary goal of this paper was first to demonstrate that health matters to political participation. We sought to achieve this aim using validated measures of voting and donations. The analysis provides a higher degree of causal persuasiveness than prior work by employing objective measures drawn from government records and in-person health measurements along with family fixed effect models that show that health continues to predict some forms of political participation even with such demanding controls. A second goal of the paper is to provide some insight into how different forms of health matter to different forms of participation. Both health and political participation have multiple dimensions, so any claim such as “health matters” is bound to be simplistic.

As future research considers this relationship among a broader population, it should continue to distinguish between different forms of health and participation. Our research offers insights to guide this work. One is that different aspects of health seem to operate differently on different forms of political participation. Health seems to matter least for donations as a form of participation, as one might expect once controls such as education, net worth, IQ, and family background are accounted for. We find that cognitive functioning is generally important, and that general functioning and physical health matters clearly for turnout in a way it does not for other forms of participation. Relying on general measures of self-reported health, as is the norm in such research, is likely to provide only a limited insight into how health matters. As future work explores the nuances of different forms of health and different forms of participation, it can better discern how health matters.

We hope that the clear influence of health on voting demonstrated here will motivate researchers to gather evidence on the precise mechanisms that make health consequential for some forms of mass participation. If the net effect of poor health is to reduce participation, certain groups of citizens are less likely to be included in democratic processes and to influence political outcomes. Inequality in health might thus create inequality in representation in ways that are correlated with health outcomes that have policy implications. Although states now offer a range of ways for people with health problems to register and vote, voting remains difficult for those with physical or cognitive impairments. In contrast, candidates and parties have essentially underwritten the costs contributing by reaching out proactively and offering numerous ways to contribute. There might be lessons here for policy makers to learn about how to facilitate voting.

Even as future work could seek to examine the role of health among a broader sample, studying health and political participation among the growing proportion of older citizens is important in its own right. Popular representations of older adults tend to focus on their generally high levels of civic engagement in democratic processes, but this masks the reality that there are troubling declines in participation in later life. For example, the positive relationship between age and voting reverses direction at about age 70, with other forms of political activity falling even more quickly (Rosenstone and Hansen 1993; Verba and Nie 1972). Understanding the degree to which ill health determines the decline in political participation among the elderly would be a significant contribution.

Supplementary Material

Data/Replication Statement.

Data and supporting materials to reproduce the results in the article are available in the JOP Dataverse (dataverse.harvard.edu/dataverse/jop). An appendix with supplementary material is available in the online edition of the article. The study was conducted in compliance with the University of Wisconsin-Madison Institutional Research Board for Education and Social/Behavioral Science. The Center for Demography of Health and Aging (CDHA) and the Graduate School at the University of Wisconsin-Madison provided financial support.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was prepared for presentation at the 2015 meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association and the 2016 meeting of the Association for Politics and the Life Sciences. We thank Nicholas Valentino for comments, Joe Savard and Carol Roan at the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) for administrative support, Adam Bonica and the Federal Elections Commission (FEC) for sharing federal campaign contribution data.

Biographical Statement

Barry C. Burden is a professor of political science at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706. Jason M. Fletcher is an associate professor of public affairs at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706. Pamela Herd is a professor of public affairs and sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706. Bradley M. Jones is a research associate at the Pew Research Center, Washington, DC 20036. Donald P. Moynihan is a professor of public affairs at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706.

Footnotes

Söderlund and Rapeli (2015) find that in Nordic countries self-reported health has a positive effect on voting but not necessarily other forms of political behavior.

Some states automatically distribute ballots by mail or allow some voters to receive a ballot by mail on a permanent basis. These practices are most common in western states where relatively few of our respondents reside.

More information about the matching process is available in the Appendix.

The data were cleaned and provided by Adam Bonica as part of the Database on Ideology, Money in Politics, and Elections. Public version 1.0. <data.stanford.edu/dime>.

By federal law, only aggregate contributions of $200 or more within an election cycle must be reported to the Federal Election Commission. The overall rate of giving we calculate is similar to that found in other surveys. The ANES is not strictly comparable because it asks about giving at any level (not just federal candidates), including giving to parties, does not omit contributions below $200, and only asks about one election cycle at a time. In the 2008 ANES, 12.8% of respondents report donating. Among those over 75, the rate is 18.6%. We calculate 15% of WLS respondents donated in at least one of the three elections between 2008 and 2012. As shown in Table A1, the rates for individual elections are 7% in 2008, 5% in 2010, and 8% in 2012. More information about the matching process is provided in the Appendix.

In the structural model, the coefficients on each of the individual items were constrained to be the same across waves of the survey. This allows us to examine changes in cognitive ability between waves for individuals who participated in both waves of the survey. We also explored simply summing up the scales into a summary measure, which produced similar results.

In our models we prioritize the correct chronological ordering of predictive variables over temporal proximity, That is, we utilize 2004 HUI and cognition measures for 2008 and 2010 outcomes and the 2011 measures for 2012 outcomes.

These correlations are based on the 2011 measures.

In Tables A7 and A8 of the Appendix we report models of voting and contributing without the health variables included. We also find similar substantive results when entering the health measures into the models sequentially rather than simultaneously.

The original WLS respondents are of similar age because they all graduated from high school in 1957. The inclusion of siblings in the sample provides variation in age, albeit skewed toward the upper end of the distribution.

Some of these variables might be considered “post-treatment” measures. Early influences such as parents’ education and IQ measured in adolescence might affect participation through intervening variables such as education, cognitive functioning, net worth, and depression. We nonetheless prefer to include these measures because we lack a firm argument or evidence about which variables might be intervening. To the degree that a variable such as education serves as the mechanism connecting health to participation, including it stacks the deck against finding effects of health variables.

Preliminary data analysis suggests that health, net worth, and education are correlated with the respondent’s state of residence. Respondents who move from their home states generally fare better on these measures.

Because health is correlated with age (Söderlund and Rapeli 2015), including age-squared is a conservative test of the effects of health.

The results appear in Table A5 of the Appendix.

The 2011 wave of the WLS also asks whether respondents tried to persuade other people to vote for or against specific parties or candidates in the 2008 election and whether they participated in a political group of union in the last year. These measures also suffer from errors and biases in self-reports and a lag between the activity and reporting about it. In Table A4 in the Appendix reports our standard models where the persuading attempt and group activity are the dependent variables. The results indicate that cognitive functioning is significantly related to persuading effort but general health is not. No health variables are significant in the models of political group activity.

This is among the civilian, non-institutionalized population. Estimates from other sources using more detailed questionnaires sometimes produce even higher estimates (Schur, Kruse, and Blanck 2013).

Recall that one third of the WLS respondents live outside Wisconsin and the age range in models including siblings starts at age 40, so the CPS categorization is stricter.

Contributor Information

Barry C. Burden, Professor of Political Science, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706

Jason M. Fletcher, Associate Professor of Public Affairs, La Follette School of Public Affairs, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706

Pamela Herd, Professor of Public Affairs and Sociology, La Follette School of Public Affairs, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706.

Bradley M. Jones, Research Associate, Pew Research Center, Washington, DC 20036

Donald P. Moynihan, Professor of Public Affairs, La Follette School of Public Affairs, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706

References

- Agree Emily M, Freedman Vicki A, Cornman Jennifer C, Wolf Douglas A, Marcotte John E. Reconsidering Substitution in Long-Term Care: When Does Assistive Technology Take the Place of Personal Care? The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2005;605:S272–80. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.5.s272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansolabehere Stephen, Hersh Eitan. Voter Registration: The Process and Quality of Lists. In: Burden Barry C, Stewart Charles., III, editors. The Measure of American Elections. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Barberger-Gateau Pascale, Commenges Daniel, Gagnon Michèle, Letenneur Luc, Sauvel Claire, Dartigues Jean-François. Instrumental Activities of Daily Living as a Screening Tool for Cognitive Impairment and Dementia in Elderly Community Dwellers. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1992;40:1129–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1992.tb01802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell-McGinty Sandra, Podell Kenneth, Franzen Michael, Baird Anne D, Williams Michael J. Standard Measures of Executive Function in Predicting Instrumental Activities of Daily Living in Older Adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2002;17:828–34. doi: 10.1002/gps.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti Yosef, Hansen Kasper M. Retiring from Voting: Turnout among Senior Voters. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion, and Parties. 2012;22:479–500. [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell DL, Lucas JW, Clark TC. Vital and Health Statistics. Washington DC: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. Summary Health Statistics for U.S. Adults: National Health Interview Survey, 2012. Series 10, Number 260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault Matthew W, Americans With Disabilities . Current Population Report. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2010. pp. P70–131. [Google Scholar]

- Burns Nancy, Schlozman Key Lehman, Verba Sidney. The Private Roots of Public Action: Gender, Equality, and Political Participation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Andrea Louise. How Policies Make Citizens: Senior Political Activism and the American Welfare State. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cesari Matteo, et al. Prognostic Value of Usual Gait Speed in Well-Functioning Older People – Results from the Health, Aging, and Body Composition Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2005;53:1675–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claggett William, Pollock Philip H., III The Modes of Participation Revisited, 1980–2004. Political Research Quarterly. 2006;59:593–600. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke Philippa J, Yan Ting, Keusch Florian, Ambrose Gallagher Nancy. The Impact of Weather on Mobility and Participation in Older US Adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105:1489–94. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comijs Hannie C, Dik Miranda G, Aartsen Marja, Deeg Dorly J H, Jonker Cees. The Impact of Change in Cognitive Functioning and Cognitive Decline on Disability, Well-being, and the Use of Healthcare Services in Older Persons. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders. 2005;19:316–23. doi: 10.1159/000084557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deary Ian J, Batty G David, Gale Catharine R. Childhood Intelligence Predicts Voter Turnout, Voting Preferences, and Political Involvement in Adulthood: The 1970 British Cohort Study. Intelligence. 2008;36:548–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher Jason M. Adolescent Depression: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Educational Attainment. Health Economics. 2008;17:1215–35. doi: 10.1002/hec.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher Jason M. The Effects of Childhood ADHD on Adult Labor Market Outcomes. Health Economics. 2014;23:159–81. doi: 10.1002/hec.2907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goerres Achim. Why are Older People More Likely to Vote? The Impact of Ageing on Electoral Turnout in Europe. British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 2007;9:90–121. [Google Scholar]

- Grigsby Jim, Kaye Kathryn, Baxter Judith, Shetterly Susan M, Hamman Richard F. Executive Cognitive Abilities and Functional Status among Community-Dwelling Older Persons in the San Luis Valley Health and Aging Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1998;46:590–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas Steven A, Fosse Nathan Edward. Health and the Educational Attainment of Adolescents: Evidence from the NLS97. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2008;49:178–92. doi: 10.1177/002214650804900205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillygus D Sunshine, Holbein John B, Snell Steven A. The Nitty Gritty: The Unexplored Role of Grit and Perseverance in Political Participation; Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association; Chicago, IL. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Horsman John, Furlong William, Feeny David, Torrance George. The Health Utilities Index (HUI®): concepts, measurement properties and applications. Health and Quality Life Outcomes. 2003;1:54. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judge James O, Schechtman Kenneth, Cress Elaine, F. I. C. S. I. T. Group The Relationship between Physical Performance Measures and Independence in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1996;44:1332–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattila Mikko, Söderlund Peter, Was Hanna, Rapel Lauri. Healthy Voting: The Effects of Self-Reported Health on Turnout in 30 Countries. Electoral Studies. 2013;32:886–91. [Google Scholar]

- Milbrath Lester W, Goel Madan Lal. Political Participation: How and Why Do People Get Involved in Politics? New York, NY: Rand McNally; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Montero-Odasso Manuel, Schapira Marcelo, Soriano Enrique R, Varela Miguel, Kaplan Roberto, Camera Luis A, Mayorga L Marcelo. Gait Velocity as a Single Predictor of Adverse Events in Healthy Seniors Aged 75 Years and Older. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2005;60:1304–09. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.10.1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njegovan Vesna, Man-Son-Hing Malcolm, Mitchell Susan L, Molnar Frank J. The Hierarchy of Functional Loss Associated with Cognitive Decline in Older Persons. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2001;56:M638–43. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.10.m638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco Julianna, Fletcher Jason. Incorporating Health into Studies of Political Behavior: Evidence for Turnout and Partisanship. Political Research Quarterly. 2015;68:104–16. doi: 10.1177/1065912914563548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkowski Jodi Messer, Berger Mark C. The Impact of Health on Employment, Wages, and Hours Worked over the Life Cycle. Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance. 2004;4:102–21. [Google Scholar]

- Pérès Karine, et al. Natural History of Decline in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Performance over the 10 Years Preceding the Clinical Diagnosis of Dementia: A Prospective Population-Based Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plutzer Eric. Becoming a Habitual Voter: Inertia, Resources, and Growth in Young Adulthood. American Political Science Review. 2002;96:41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood Kenneth, Mitnitski Arnold B, MacKnight Chris. Some Mathematical Models of Frailty and Their Clinical Implications. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology. 2002;12:109–17. [Google Scholar]

- Royall Donald R, Palmer Raymond, Chiodo Laura K, Polk Marsha J. Declining Executive Control in Normal Aging Predicts Change in Functional Status: The Freedom House Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:346–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker Jason, Behrman Jere R. Learning to Do well or Learning to Do Good? Estimating the Effects of Schooling on Civic Engagement, Social Cohesion, and Labor Market Outcomes in the Presence of Endowments. Social Science Research. 2012;41:306–320. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schur Lisa, Kruse Douglas. Disability and Election Policies and Practices. In: Burden Barry C, Stewart Charles., III, editors. The Measure of American Elections. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schur Lisa, Kruse Douglas, Blanck Peter. People with Disabilities: Sidelined or Mainstreamed? New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Söderlund Peter, Rapeli Lauri. Personal Health and Political Participation in the Nordic Countries. Politics and the Life Sciences. 2015;34:28–43. doi: 10.1017/pls.2015.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strate John M, Parrish Charles J, Elder Charles D, Ford Coit., III Life Span Civic Development and Voting Participation. American Political Science Review. 1989;83:443–64. [Google Scholar]

- Studentski Stephanie, et al. Gait Speed and Survival in Older Adults. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;305:50–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatemichi TK, Desmond DW, Stern Y, Paik M, Sano M, Bagiella E. Cognitive Impairment after Stroke: Frequency, Patterns, and Relationship to Functional Abilities. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 1994;57:202–7. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.57.2.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teachman Jay. Work-Related Health Limitations, Education, and the Risk of Marital Disruption. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:919–32. [Google Scholar]

- van Kan G Abellan, et al. Gait Speed at Usual Pace as a Predictor of Adverse Outcomes in Community-Dwelling Older People: An International Academy on Nutrition and Aging (IANA) Task Force. Journal of Nutrition, Health, and Aging. 2009;13:881–9. doi: 10.1007/s12603-009-0246-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vavreck Lynn. The Exaggerated Effects of Advertising on Turnout: The Dangers of Self-Reports. Quarterly Journal of Political Science. 2007;2:325–43. [Google Scholar]

- Verba Sidney, Nie Norman H. Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Verba Sidney, Schlozman Kay Lehman, Brady Henry E. Voice and Equality: Civic Volunteerism in American Politics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Warren John Robert. Socioeconomic Status and Health across the Life Course: A Test of the Social Causation and Health Selection Hypothesis. Social Forces. 2009;87:2125–53. doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widera Eric, Steenpass Veronika, Marson Daniel, Sudore Rebecca. Finances in the Older Patient with Cognitive Impairment: ‘He Didn't Want Me to Take Over’. JAMA. 2011;305:698–706. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinger Raymond E, Rosenstone Steven J. Who Votes? New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Yonker James A, Hauser Robert M, Freese Jeremy. The Dimensionality and Measurement of Cognitive Functioning at Age 65 in the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study. Center for Demography and Ecology Working Paper 2007-06 2007 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.