Abstract

Purpose

This study examined effects of a peer-mediated intervention that provided training on the use of a speech-generating device for preschoolers with severe autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and peer partners.

Method

Effects were examined using a multiple probe design across 3 children with ASD and limited to no verbal skills. Three peers without disabilities were taught to Stay, Play, and Talk using a GoTalk 4+ (Attainment Company) and were then paired up with a classmate with ASD in classroom social activities. Measures included rates of communication acts, communication mode and function, reciprocity, and engagement with peers.

Results

Following peer training, intervention effects were replicated across 3 peers, who all demonstrated an increased level and upward trend in communication acts to their classmates with ASD. Outcomes also revealed moderate intervention effects and increased levels of peer-directed communication for 3 children with ASD in classroom centers. Additional analyses revealed higher rates of communication in the added context of preferred toys and snack. The children with ASD also demonstrated improved communication reciprocity and peer engagement.

Conclusions

Results provide preliminary evidence on the benefits of combining peer-mediated and speech-generating device interventions to improve children's communication. Furthermore, it appears that preferred contexts are likely to facilitate greater communication and social engagement with peers.

Many benefits of teaching young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) to use a speech-generating device (SGD) as an augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) system have been documented (see reviews by Lancioni et al., 2007; van der Meer & Rispoli, 2010). Children who are nonverbal or minimally verbal have learned to use SGDs for a number of communication purposes, including requesting, commenting, taking turns, and learning new vocabulary (Bock, Stoner, Beck, Hanley, & Prochnow, 2005; Brady, 2000; Kasari et al., 2014; Schlosser, Sigafoos, & Koul, 2009). SGD interventions can augment children's existing communication skills, which can then lead to greater participation in daily activities with classmates and others (Sevcik, Barton-Hulsey, & Romski, 2008). For young children with ASD educated in inclusive environments, peer-mediated interventions (PMIs) have much research support on improving social communication—a core deficit of this disorder (Chan et al., 2009; Goldstein, Lackey, & Schneider, 2014; Reichow & Volkmar, 2010). Combining these two evidence-based interventions would increase our knowledge on how to better support communication by incorporating AAC to promote social engagement with typically developing peers in preschool and beyond.

SGD Interventions for Children With ASD

Literature reviews on AAC use with children with developmental disabilities, including ASD, have reported clear evidence that SGD systems can enhance language and communication (Lancioni et al., 2007; Romski, Sevcik, Barton-Hulsey, & Whitmore, 2015). In an effort to guide evidence-based decision making for incorporating SGDs in communication interventions, van der Meer and Rispoli (2010) reviewed 23 studies that included 51 participants with ASD between the ages of 3 and 16 years. Of these, 78% were classified as demonstrating conclusive evidence of positive outcomes. Specific to children with ASD, the evidence shows that SGD interventions can enhance communication functions, gestures, vocalizations, spoken words, expressive language skills, and receptive vocabulary (Kasari et al., 2014; Olive et al., 2007; Schepis, Reid, Behrmann, & Sutton, 1998). For example, Olive and colleagues (2007) combined enhanced milieu teaching with a Cheap Talk 4 In-line Direct SGD (Enabling Devices) to improve requesting skills of three preschool children with severe autism. Trainers taught the children to push a button to request preferred items using natural reinforcers, arranging the environment, and following the child's lead. All three children showed increased SGD use with adult communication partners.

Within preschool classrooms, there are many daily routines that provide opportunities to teach functional communication to young children with ASD learning to use AAC. Naturalistic teaching procedures have been used to teach communication skills that may lead to natural consequences by taking advantage of naturally occurring environments that have reinforcing value to the child (Koegel, 1995; Koegel, O'Dell, & Koegel, 1987). Schepis and colleagues (1998) examined the effects of combining naturalistic teaching procedures and SGD instruction with four preschool children with ASD. This study was notable because it measured child–child communication in addition to child–adult outcomes during play and snack contexts. The authors reported increased social comments, requests for preferred items, and responses with adult communication partners. But child–child communication was absent for three of the four children. Notably, the study took place in a self-contained classroom in which all children had ASD and significant communication deficits. The finding that one child increased communication during snack suggests that receiving a preferred food item may be a natural consequence that can impact functional communication for children with ASD interacting with peers without disabilities.

Combining Peer-Mediated and SGD Interventions

Given the pervasive deficits in socialization and communication characteristic of children with ASD, especially those with complex communication needs learning to use AAC, identifying effective approaches to improve social communication with peers in typical preschool social and educational settings is of critical importance. Researchers have found that when this population learns to interact with typically developing peers, there is a greater reduction in core deficits in communication, joint engagement, and play skills (Freeman, Gulsrud, & Kasari, 2015; Sigman et al., 1999). PMIs are considered an evidence-based approach to improve cardinal deficits of autism related to communication, reciprocal social interactions, and restricted play (Chan et al., 2009; Goldstein et al., 2014; National Autism Center, 2015). This approach involves instructing typically developing peers how to initiate, respond to, and reinforce communication attempts of children with ASD in planned social activities (Goldstein, Schneider, & Thiemann, 2007; Thiemann & Goldstein, 2004). However, despite growing knowledge of how to improve communication of children with ASD using SGDs, we know little about intervention strategies to increase augmented communication with peers. Lancioni and colleagues (2007) examined evidence available over a 15-year period on the use of voice output communication aides (another term for SGDs) as part of AAC interventions designed to impact requesting behaviors for students with developmental disabilities, including autism. They reviewed 16 studies that included 39 participants and reported that 92% (all but three individuals) demonstrated some success in learning to request items such as food and preferred toys or to ask for help. None of these studies included peers without disabilities in the intervention procedures; to date, studies have reported communication outcomes primarily with teachers, classroom aides, parents, and research staff (Olive et al., 2007; Romski et al., 2010; Schepis et al., 1998).

There are several potential benefits of combining PMIs with SGD interventions. First, peers taught to use the same AAC system can provide models or augmented input, which may then lead to greater AAC use by the child with ASD (Trottier, Kamp, & Mirenda, 2011). Second, when peers are taught the same vocabulary and symbols, they can respond more consistently to child communication attempts, especially for children with ASD who are nonverbal or have limited or unintelligible speech. Third, encouraging SGD use across different classroom activities and communication partners may lead to improved generalization of skills (Trembath, Balandin, Togher, & Stancliffe, 2009). Fourth, children with ASD who engage in successful interactions may develop a greater desire to observe and imitate peers—precursors to learning essential social communication skills (Garfinkle & Schwartz, 2002). Thus, mutual access to the same system may allow for greater social participation, natural feedback from peers, and increased motivation based on subsequent communication success.

Results from the few studies reporting on combined PMI and SGD intervention approaches have confirmed some of these benefits. For two 11-year-old students with ASD, Trottier et al. (2011) successfully taught six typically developing peers to prompt SGD use during Bingo and Concentration card games. Both students with ASD increased spontaneous communicative acts to their peers. Unfortunately, changes in peer communication behaviors were not reported, and the peers were not taught to use the SGD to provide augmented input or to communicate. Furthermore, outcomes were measured in only one activity (game play), and no data were provided on treatment fidelity related to peer training. In one of the few studies with preschoolers, Trembath et al. (2009) examined the effects of combining PMI with naturalistic teaching approaches on the communication behaviors of three children with ASD in settings with and without an SGD. Six peers received two 20-min sessions of training without the focus child, and the naturalistic teaching procedure was broken down into three steps: show, wait, and tell. Sessions occurred during child-selected play activities and snack/meal time. Results revealed that the two children with ASD produced more communication behaviors with peers during play activities that included the SGD, and all children demonstrated minimal increases during snack (i.e., one act per min). A similar limitation to other research was the absence of measures of changes in peer communication. Reporting on the effects of PMI and AAC interventions for both children with ASD and trained peers is essential to understand how these combined interventions may improve rates of communication and social reciprocity, marked deficits for this population.

Thiemann-Bourque, Brady, McGuff, Stump, and Naylor (2016) recently addressed this need by developing and examining a combined AAC intervention that taught peers without disabilities to use Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS; Bondy & Frost, 1994) with four minimally verbal preschoolers with ASD. Peers were taught to Stay–Play–Talk (English, Goldstein, Shafer, & Kaczmarek, 1997; Goldstein, English, Shafer, & Kaczmarek, 1997), with the Talk phase modified to include learning how to communicate with classmates with ASD who exchanged a picture for preferred items. Results revealed marked improvements in PECS use within natural routines (e.g., centers, sensory activities, and snack) for all four children with ASD and increased peer communication. Given the nature of PECS, rates of initiations were higher for the children with ASD, and conversely rates of responses were higher for the peers. Peers were responsible for taking the picture from the child's hand and placing it back on the PECS book, which often interfered with the naturalness of the exchange. The authors also observed increased peer-directed communication and social engagement for two children when the context changed from centers to snack. For one child, they noted that snack became a positive social experience based on increased positive affect and communication with peers; however, another child seemed to communicate strictly for instrumental reasons (i.e., to obtain a snack from peer). These observations led to the current study to explore changes in child communication across contexts (i.e., centers, cause–effect toys, and snack) and to examine the effects on the balance of communication exchanges (i.e., initiations and responses) following peer training and instruction on use of an SGD as opposed to PECS.

In summary, effective interventions to improve social communication for children with autism who are nonverbal or minimally verbal and learning to use AAC remains a crucial unmet need. Although AAC interventions have much research support on increasing children's communication, outcomes are primarily measured with adult partners. The purpose of this study is to address this gap by examining the effects of combining SGD instruction and peer-mediated teaching approaches on children's communication and social interactions in typical preschool contexts. The primary research questions were as follows: (a) What are the effects of combining a PMI and SGD instruction on communication, reciprocal interactions, and engagement between nonverbal/minimally verbal preschool children with ASD and typically developing peers? (b) To what extent does adding preferred toys and snack as social contexts affect child and peer communication and levels of engagement?

Method

Participants

Three preschoolers with autism and three peers who were typically developing from the same classroom participated. Each peer was paired with one child with autism for the duration of the study. Pairings were decided by the classroom teacher based on her insights and observations of peer receptiveness and sensitivity to the classmate with ASD. Parental consent was obtained for all six children, referred to by pseudonyms.

The children with ASD included two boys and one girl with ages from 4;5 to 4;7 years;months (see Table 1 for demographic information). They attended the same preschool classroom located in a public elementary school building. The preschool was in session for 3 hr per day, 4 days per week. It was an inclusive environment with individualized early intervention services provided in class and pullout. A child was included in this study if he or she (a) received a diagnosis of ASD by a community-based developmental pediatrician; (b) was nonverbal or minimally verbal (defined as less than 20 spontaneous words), confirmed by direct observations and teacher report; (c) was recommended by the education team as a candidate for learning to use an SGD as an AAC system; (d) spoke English as the primary language in the home; and (e) showed limited peer interaction skills based on teacher report using a 15-item Social Impression Rating Scale (SIRS; adapted from Odom et al., 1997). The Preschool Language Scale–Fourth Edition (Zimmerman, Steiner, & Pond, 2002) was administered to all three children at the onset of this study to describe individual language skills (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of children with autism spectrum disorder at the start of the study.

| Child | Gender | Age (years; months) | Diagnostic instrument | Autism severity | PLS-4 total SS | PLS-4 AC SS | PLS-4 EC SS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jaime | M | 4;6 | ADOS | Severe | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Laney | F | 4;5 | ADOS | Severe | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Daniel | M | 4;7 | ADOS | Severe | 50 | 50 | 50 |

Note. ADOS = Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule; PLS-4 = Preschool Language Scale–Fourth Edition; SS = standard score; AC = Auditory Comprehension; EC = Expressive Communication; M = male; F = female.

Jaime, age 4;6 years, was in his second year at the preschool. He had an expressive vocabulary of less than 20 spontaneous words to request food or preferred toys and was beginning to occasionally echo adult speech. He received up to 90 min of speech-language therapy per week. He was not using any type of AAC system at the start of the study. Lead teacher ratings on the SIRS revealed limited interactions with his peers, with a total score of 21 out of 75 possible (15-item scale, where 5 is the highest possible rating), resulting in an average of 1.4 across all 15 items (i.e., “Never” to “Rarely” engaged in peer-directed social behaviors).

Laney, age 4;5 years, was in her second year at the preschool. She had an expressive vocabulary of approximately 10 words to request “more,” to label preferred toys (i.e., music, baby), and to ask for food items. Laney received up to 90 min of speech-language therapy per week and was not using any type of AAC system to communicate independently at the start of the study. When expected to attend to academic or nonpreferred tasks, she often became aggressive toward adults. She also received behavioral support services to help teachers manage escape and avoidance behaviors. Laney received a total score of 20 (out of 75) on the SIRS completed by the lead teacher, resulting in an average score of 1.3 across the 15 items (i.e., “Never” to “Rarely” engaged in peer-directed social behaviors).

Daniel was 4;7 years at the start of the study and in his second year of the preschool program. He was not yet expressing words and communicated primarily through gestures or pushing/pulling adults by the hand. Parents reported that he could vocalize vowel sounds and did not produce any consonants. He received up to 90 min of speech-language therapy per week and had just been introduced to PECS prior to the start of the study. Daniel had an average item score of 1.1 (i.e., all social items rated as “Never” except for two—appears to be having fun and stays close to peers) across all 15 items on the SIRS, with a total score of 17.

The peers without disabilities included one boy and two girls and ranged in age from 4;5 to 4;6 years old. A peer was included in the study if he or she (a) demonstrated age-appropriate social skills based on teacher report, (b) had consistent school attendance, (c) expressed a willingness to participate, and (d) was able to attend to teacher-directed lessons for a minimum of 20 min.

Settings

One lead teacher and two to three paraprofessionals staffed the classroom. The preschool provided a transdisciplinary team approach, with center-based services including speech-language pathology, occupational therapy, physical therapy, social work, and school psychology. The ratio of peers to children with developmental disabilities for this classroom was 1:2. Peer training sessions took place in an empty therapy room. Initially, all baseline and intervention sessions took place across typical preschool center activities as recommended and planned by the lead teacher. These included art (e.g., play dough and bingo markers), floor play (e.g., dollhouse and blocks with cars), and tabletop activities (e.g., puzzles, sorting, and coloring). Across all baseline and intervention sessions, the focus child and peer sat on the floor or at a table near other children in the classroom. Other adults in the classroom were in proximity and were involved with other children in similar activities. The lead teacher occasionally sat with the group to encourage participation given her familiarity with the children. In an effort to explore if child-preferred cause–effect toys with lights/sounds would increase child motivation to communicate, the first author recommended these types of toys after the first 6 weeks of intervention. For the final 2 weeks of intervention, a snack context was added to further examine this added social context and generalized effects on child–peer communication. Snack took place in the classroom at a table and included the focus child and his or her trained peer.

Experimental Design

A multiple probe design across participants was used to examine the effects of the intervention on rates of communication, reciprocity, and engagement (Horner & Baer, 1978; Horner et al., 2005). Zero baselines for focus child communication acts were evident in five to seven sessions probed over 19, 26, and 36 days, respectively. Given that all children demonstrated stable baselines, with zero communication acts, they all met criteria to move to the peer training phase; Jaime was selected to start first as he had the most consistent school attendance. During peer training, child–peer classroom observations for that dyad were suspended. Due to Laney's absences after the first intervention session following peer training, the timing of the staggering of intervention initiation was compromised, with Daniel entering intervention before effects were shown for Laney. For Laney's first three intervention sessions, all communication acts were prompted by the adult.

Dependent Variables and Data Collection

All sessions were videotaped using a Flip Mino Video Camera (1st generation, Flip Video) on a tripod set up near the dyad. The primary coder collected data on all dependent variables live during the session using a paper-and-pencil system, with a 15-s interval tape positioned near the camera. The video was available for a second viewing by the primary coder if necessary and was used for coding by the reliability coder. Dependent variables included total rates of focus child and peer initiations and responses, mode of communication, and function of the communication act within each 6-min social activity. No adult-directed communication was coded or included in the totals. The total number of adult prompts to the focus child or peer was coded and included any verbal or physical acts to prompt use of speech, the SGD, or gestures (e.g., to give toys upon request). Data across baseline and intervention were summarized separately for adult-prompted and spontaneous child and peer communication (see Figures 1 and 2).

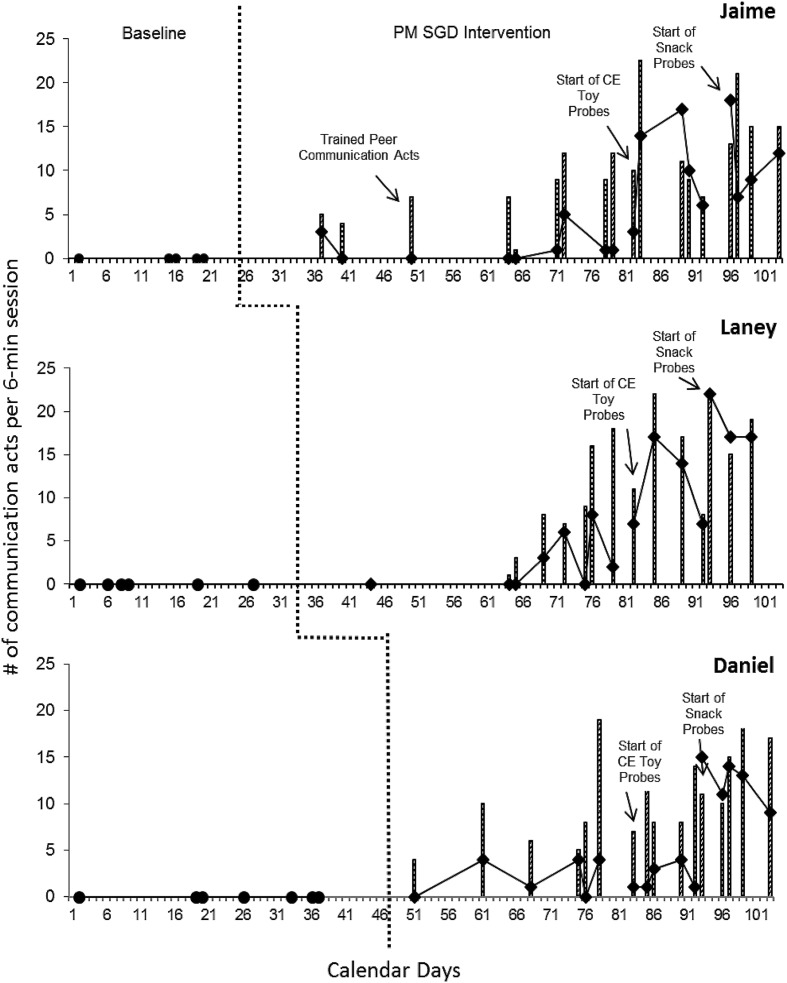

Figure 1.

The total number of spontaneous, unprompted communication acts directed to peers by the children with autism spectrum disorder is represented by the line graphs. The bar graphs indicate the total number of adult prompts to the focus child. PM SGD = peer-mediated speech-generating device; CE = cause–effect.

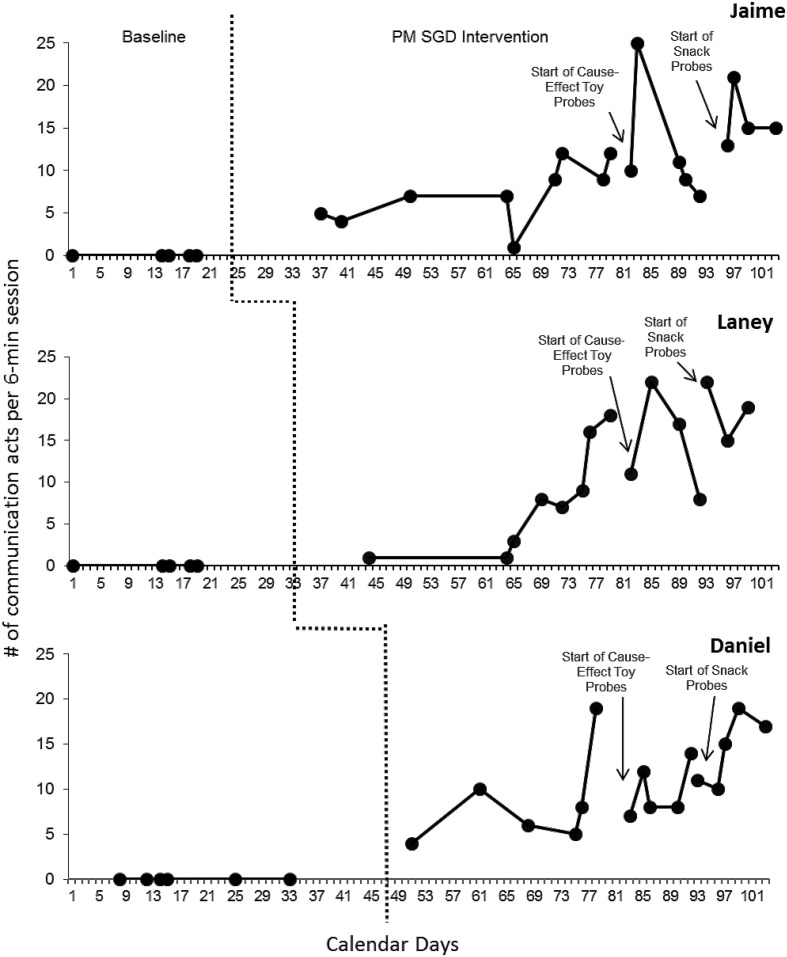

Figure 2.

Total number of spontaneous communication acts directed to children with autism spectrum disorder by trained peer partners. PM SGD = peer-mediated speech-generating device.

Focus Children's Communication

All focus child communication acts directed to peers were coded using event recording or total frequency of acts for a 6-min interval during the social activity. An interval of 6 min was selected as the observation interval as we had previously documented changes in child and peer communication behaviors with PECS using a similar coding interval system (Thiemann-Bourque et al., 2016). A communication act was coded as an initiation if a minimum of 3 s passed since the last communication act. A response by the focus child to his or her peer was coded if the communication act followed within 3 s of a peer's initiation or response. Multiple responses following an initiation could be coded (e.g., I-R-R-R) as long as the response was by a different communication partner (i.e., alternating responses to the previous communication act) and it was observed within 3 s of the last communication act. If there was a full 3-s pause, the next act was coded as another initiation.

Once an initiation or response was coded, the type of communication mode was noted as (a) speech, (b) SGD, or (c) gesture. Finally, the function of the communication act was then coded based on the following four possibilities: (a) gain attention, (b) comments, (c) requests, and (d) shares (see Table 2 for definitions). Immediate echolalia of an adult or peer utterance was not coded as spontaneous child speech. Other or inappropriate behaviors coded included disruptive physical behaviors (e.g., hitting and throwing toys), noninteractive, delayed echolalia (e.g., repetitions of movie lines or shows that did not relate to the immediate context), or unintelligible speech. The total number of spontaneous communication acts for each focus child was summed and averaged across baseline and intervention phases. Only communication acts directed to a peer partner or peer partner to a focus child were coded; speech directed to any adult was not coded.

Table 2.

Definitions of coded communication modes, behaviors, and functions.

| Coded item | Definition |

|---|---|

| Communication modes | |

| Speech | Child intentionally uses speech to communicate with a peer; minimum requirements to code as speech included (a) one consonant and one vowel combination, (b) approximation of words included one consonant matching placement in the intended word, and (c) verbalization directed to peer. |

| SGD | Child intentionally pushes button(s) on SGD to communicate with peer. |

| Gesture | Child uses any conventional gesture to communicate with peer (e.g., point, wave, head nod, head shake). |

| Communication behaviors | |

| Initiation (FI or PI) | Child initiates by communicating using any mode described above. An initiation is coded if a minimum of 3 s passed after the last focus child or peer communication act. Multiple or sequential FIs or PIs can be coded if a minimum of 3 s separates each communication act. |

| Response (FR or PR) | Child responds to another child's initiation or response by communicating using any communication mode within 3 s of the child's initiation. Multiple FRs or PRs can be coded if responsive acts occur within 3 s of previous focus child or peer communication act. If child is being prompted to use SGD, code as FR if it takes more than 3 s for prompt to be successful. |

| No response (FNR or PNR) | Child does not respond to another child's communication act within a 3-s interval of the child's communication act. |

| Communicative functions | |

| Gain attention | Requests the other child's attention (e.g., say child's name, tap on shoulder). |

| Comment | Labels object by name, color, size, or other descriptive words (e.g., puzzle, music, red one); acknowledges or agrees with other's comments (e.g., yes, okay); uses socially polite words (e.g., please, thank you). |

| Requests | Requests to get an object (e.g., puzzle piece, cracker please), to have another child perform an action (e.g., put it in, push it), or to talk about turns (e.g., my turn, your turn). |

| Shares | Offers a toy or materials when items or continuation of play is requested (e.g., hands toy to child and says, “Here you go”). |

| Other | Disruptive or inappropriate vocalizations or physical behaviors (e.g., hitting, throwing toys, yelling, or crying); noninteractive, delayed echolalia that does not relate to context (e.g., noncommunicative repetitions of movie lines, shows, memorized scripts); animal noises or unintelligible utterances; stereotypic or perseverative behaviors deemed to be self-stimulatory and take peer's attention from current activity. |

Note. SGD = speech-generating device; FI = focus initiation; PI = peer initiation; FR = focus response; PR = peer response; FNR = focus no response; PNR = peer no response.

Trained Peers' Social Communication

All peer communication directed to the focus child was coded using event recording or total frequency of acts during the same 6-min coding interval and the same operational definitions of behaviors. That is, total rates of initiations and responses, the mode of each communication act, and the function of the communication act were coded for all peer acts. The total number of spontaneous communication acts for each trained peer was summed and averaged across baseline and intervention phases. Peer speech directed to adults was not coded, and any peer communication act prompted by the adult was not counted in the totals summarized across baseline and intervention conditions.

Communication Reciprocity

Reciprocity of communication was measured by totaling the number of separate reciprocal exchanges between the focus children and peers. Reciprocity was defined as a minimum of one initiation by either communication partner, followed by one response by the opposite communication partner (i.e., focus child initiation followed by any peer response, or a peer initiation followed by a focus child response coded as one exchange). One reciprocal exchange could include an initiation followed by one response or an initiation followed by multiple alternating responses by the partners. A new initiation by the focus child or a peer ended each reciprocal communication exchange. The total number of all exchanges that contained a minimum of one initiation and one response was tallied and graphed for each session.

Engagement With Peers

Engagement with peers was defined as the focus child staying within 2 ft of the peer and actively participating in the designated social activity by showing interest or watching the peer, sharing or giving toys, orienting body and/or shoulders toward the peer, and talking to or responding to the peer. Engagement was coded using a whole interval recording system for six 1-min intervals. Coders marked engagement across Intervals 1 through 6 on the same coding sheet used for coding primary dependent variables. The child was considered to be engaged for each 1-min interval if he or she maintained one or more of the defined behaviors for a minimum of 45 s of each 1-min interval. The 15-s interval tape used to code the dependent variables allowed staff to mark engagement at each of the six 1-min intervals. The total number of intervals the child was engaged with the peer was summed for each session. This total was then divided by the number of sessions to report an average rate of engagement per phase.

Procedure

Baseline

During baseline, each child with ASD was paired with one peer. The first or second author explained the activity and told the pair to stay at the table and play nicely. Adult prompts were provided only if a child left the group and needed assistance to return. A GoTalk 4+ (Attainment Company) was placed on the table between the two children; no prompts were provided for how to use this AAC system. The speech-language pathologist (SLP) on the child's educational team was consulted to determine the appropriateness of using the GoTalk 4+ for all three children. This device was considered to be appropriate given that all children were beginning SGD users, they were able to discriminate between two and four pictures, and a peer's voice could be recorded in the moment to match selected vocabulary. The SLP provided further guidance on the selection of vocabulary and symbols to use on the grid layouts based on her knowledge of each child's communication competencies. For each activity, two to four pictures were placed on a print overlay that slid into the GoTalk 4+. The pictures were photographs or Boardmaker (Boardmaker, 2014) symbols of the objects to be used within the activity. The GoTalk 4+ has four main 3-in. square keys and two core message keys that remain constant above the four main keys. A participating peer was asked to record a single word or a two-word phrase on the main keys to request objects (e.g., “ball please” and “more puzzles”) and one social comment on each of the two smaller keys (e.g., “you did it!” and “let's play”). Multiple overlays were created to match the context of each social activity and placed in the GoTalk 4+ just prior to the interaction. Total frequencies of all primary dependent measures were collected live in baseline during a 6-min coding interval.

Peer-Mediated SGD Training

The first and second author provided SGD training to peer partners separately, during 30-min sessions for 3 days in a quiet room. Children with ASD did not attend these sessions. Peers were taught to be responsive communicators and play partners using a social intervention called Stay–Play–Talk (English, Goldstein, et al., 1997; English, Shafer, Goldstein, & Kaczmarek, 1997; Goldstein et al., 1997). Modification for this study included (a) breaking down Stay, Play, and Talk into substeps, with pictures and words created to match each skill, that were then visually depicted in a Buddy Book; (b) using the Play steps “share toys” and “take turns playing” but not establishing mutual attention or suggesting playing together or talking about the activity as in the original studies; and (c) teaching SGD use as one way to Talk within the third peer training step. In addition, the children were taught More Ways To Be a Good Buddy, which included two skills: (a) getting their buddy's attention and (b) hold and wait (i.e., as a delayed prompt to elicit focus child communication). Components of each peer training session included (a) providing each peer with a Buddy Book with colored pictures and words to describe each step, (b) adult–adult role play of substeps, (c) adult–child role play of substeps, (d) adult feedback and reinforcement of skill use, and (e) review of steps taught.

Peer-Mediated SGD Intervention in the Classroom

Following peer training, the trained peer was paired up with one child with autism in a classroom social activity. During center activities, the teacher recommended activities based on what was set up for all children in the classroom and what she thought would be motivating for each child. Research staff implemented intervention sessions twice per week, and the intervention ranged from 15 to 18 sessions over the course of 10 weeks. For approximately 5 min just prior to the activity, the implementer reviewed the social activity, showed the children a laminated 8 × 8 Stay–Play–Talk sign, provided modeled input of the symbols on the SGD, and guided both the peer and focus child to engage in two successful reciprocal interactions. The implementer then moved slightly behind or to the side of the dyad to observe. If no communication was observed after approximately 30 s, the adult prompted the focus child or the peer to initiate (or to respond if that was more appropriate based on the social situation) using the SGD. Prompts were provided in a least-to-most hierarchy: (a) adult told the child to (for example) “ask your friend for _____,” (b) adult pointed to the SGD symbol and said “ask your friend for _____,” and (c) adult used hand-over-hand cue to help the child communicate to peer (or vice versa) by pushing an appropriate button. No prompts were provided if the implementer observed spontaneous communication either with or without the SGD.

After 6 weeks of intervention, the authors explored whether a change in play context would increase child–peer communication. After consulting with the lead teacher, cause–effect toys with lights and sounds were deemed preferred and were introduced to each dyad over four to five sessions. The symbols or vocabulary on the SGD were changed accordingly to match the communicative context of the new toys (e.g., to request the toy, to request more). Once changes were noted, the authors then explored the effects of a snack context on child–peer communication over three to five sessions. The GoTalk 4+ was available for the classroom teacher and SLP to use outside of intervention days. The lead teacher reported that she used the system a few times with all children within the last month of intervention primarily during snack and table time center activities.

Data Analysis

Effects of the peer-mediated SGD intervention on communication, reciprocity, and engagement variables were examined using a combination of visual analyses and calculation of effect sizes between baseline and the first intervention condition—centers. Visual analysis of the graphed data included a description of differences between baseline and the intervention phases in relation to variability, mean, and trend (Horner et al., 2005). Tau-U effect sizes (Parker, Vannest, Davis, & Sauber, 2011) were calculated to provide a quantitative measure of the degree of change between baseline and the first intervention phase only, given that the addition of the cause–effect toys and the snack context was exploratory and not present in baseline. Tau-U effect sizes were calculated for the degree of change for each child with autism and also for the change in peer communication. An overall Tau-U effect size was then calculated across all three children with ASD and all three peers to determine magnitude of change for each group. Tau-U effect sizes of < .5, .5–.69, and .70–1.0 are interpreted as minimal to no effect, moderate effect, and a large effect, respectively.

Reliability

A minimum of 30% of all baseline and intervention sessions were coded independently to estimate reliability for communication mode (speech, SGD, gesture), behaviors (initiations, responses), and functions (gain attention, comments, requests, shares). Two research assistants (RAs), an undergraduate student, and the second author learned to code primary dependent measures to a criterion level of 80% prior to coding independently. After practice coding on videos of dyads from a previous study, each RA coded live in the classroom with the first author for three sessions to reach an interobserver agreement criterion of 80% or greater. A prerecorded 15-s interval tape was set up next to the camera microphone to assist with reliability coding. When possible, the two coders coded simultaneously during the intervention session; otherwise, the RA coded off of a videotape of the session. Agreements were scored if both observers coded the same communication mode, behavior, or function in the same 15-s interval. Disagreements were counted if the two coders disagreed on the type of mode, behavior, or function of the act, or if one coder did not observe an act (i.e., a miss). Percent agreement was calculated separately for each of these three communication measures by dividing the agreements by agreements plus disagreements then multiplying by 100 to yield a percentage. In baseline, the average values of interobserver reliability were 99% (range of 92%–100%) for communication mode, 99% (range of 92%–100%) for behaviors or acts, and 98% (range of 92%–100%) for communicative functions. In the intervention phase, the average values of interobserver reliability were 90% (range of 80%–100%) for communication mode, 85% (range of 76%–100%) for all communication behaviors, and 99% (range of 96%–100%) for the function of the communication act.

Teacher Fidelity of Implementation

Researchers completed a checklist of 10 steps to ensure fidelity of implementation of the intervention. Items on the checklist related to setup of the social environment for each session, implementer instruction and modeling of the SGD, guiding child–peer practice, the length of the session, and prompting of student responses. Research staff observed implementation and completed the checklist for 41% of the intervention sessions. Fidelity of intervention ranged from 86% to 100% with an average of 92% across all sessions.

Results

Figure 1 shows the frequency of all communication behaviors (initiations plus responses) during baseline and each intervention condition for the focus children with ASD. The frequency of focus child acts includes only spontaneous initiations and responses directed to a trained peer and is represented by the line graph. The bar graph represents all adult prompts provided to the focus child during each intervention session. Figure 2 shows the total number of peer communication acts directed to the focus child. There were no communication acts directed by the peers to the focus children in baseline nor by the focus children to the peers. The effects of the peer-mediated SGD intervention are evident based on the improvements in the higher levels of communicative acts. This was demonstrated for all three children with autism and across the three trained peer partners, suggesting a functional relationship between the start of the intervention and changes in children's communication skills.

Focus Children's Social Communication

Over the course of 18 intervention sessions over 10 weeks, Jaime increased his communication behaviors from an average of zero in baseline to six acts per intervention session. Immediately following peer training, Jaime's first intervention session during centers showed an increase in total acts (three); however, with the exception of his seventh intervention session when he spontaneously used five acts, Jaime continued to require adult prompts to interact with his peer (i.e., average of eight prompts per session) during centers. His average rate of acts across all nine sessions in the centers context was 1.2 per session. When the cause–effect toy context was introduced, Jaime's average rate of communication acts increased to 10 per session. A further increase to an average of 11.5 acts per session was noted when the snack context was introduced. Overall, adult prompts during intervention averaged seven per session or just over one per minute. The majority of Jaime's communication was through SGD use (73% of all acts), followed by the use of gestures (13%) and SGD plus speech (9%). In four instances he used speech only (4%), and in one instance he combined speech and a gesture (1%). The primary function of Jaime's communication to peers was to make requests (71% of acts), and he was also observed to share toys/objects (24%). He rarely communicated to comment (3%) or to gain a peer's attention (2%).

Immediate treatment effects during centers were not observed for Laney's spontaneous communication acts, and adult prompts were necessary to increase peer-directed communication (i.e., average of seven prompts per session). After her third intervention session, however, Laney's spontaneous communication acts started to increase but remained variable, with an average of 2.4 acts across all center condition sessions. Her average rate of communication acts to peers increased markedly to an average of 11.3 when the cause–effect toy context was introduced, and her rates were even higher when the three snack sessions were introduced (i.e., average of 18.7 acts per session). Adult prompts to Laney averaged five per session during intervention or just less than once per minute. During intervention, Laney's primary mode of communicating to peers was SGD use (87%), followed by gestures (12%), and she used SGD combined with speech on two occasions. Laney showed improvements primarily for two different communicative functions: requests (88% of acts) and shares (11% of acts). On one occasion, she initiated to gain a peer's attention (1%).

Similar to the other two children with ASD, Daniel expressed no communication to peers during baseline. Although variable, Daniel's rates of initiations and responses to peers improved slightly, fluctuating between zero and four acts per session during centers (M = 2.2 acts). Minimal changes were observed when cause–effect toys were introduced, with an average of 2.0 spontaneous acts per session. However, immediate and marked treatment effects were observed with the introduction of snack. His rates remained high for the last five snack intervention sessions, with a mean of 12.4 acts. Adult prompts to Daniel averaged six per session during intervention or once per minute. Daniel's primary mode of communication to peers was SGD use (87% of all acts), followed by gestures (13%). He was not observed to combine different modes of communication. He communicated primarily for making requests (93%), and the remaining acts were to share (4%) or gain a peer's attention (4%).

Trained Peers' Social Communication

Following peer training, immediate treatment effects were observed for Jaime's and Daniel's peers, and a more gradual effect was noted for Laney's peer (see bar graphs in Figure 1). Over the course of the centers condition, peers for Jaime, Laney, and Daniel increased their spontaneous communication acts to an average of 7.3, 7.8, and 8.7 per session, respectively. The introduction of cause–effect toys resulted in marked increases in spontaneous communication for two of the trained peers, for Jaime (M = 12.4 acts) and Laney (M = 14.5 acts), and a smaller increase for Daniel's peer (M = 9.8 acts). Analysis of peer communication data collected during snack showed continued improvements, with Jaime's peer increasing to an average of 16 acts, Laney's peer increasing to an average of 18.7 acts, and Daniel's peer increasing to 14.4 acts.

Tau-U Effect Sizes for Focus Children and Peers

Tau-U calculations revealed moderate effect sizes for all three participants with ASD. Calculated effect sizes were .56 for Jaime, .50 for Laney, and .67 for Daniel. The combined calculated Tau-U across all three children with ASD also indicated a moderate magnitude of change (.57) from baseline to intervention during centers. Analyses for the peer partners demonstrated large effect sizes between baseline and the center intervention condition, with Tau-U of 1.0 for Jaime's peer, .88 for Laney's peer, and 1.0 for Daniel's peer. The calculated Tau-U for all peers combined also indicated a large magnitude of change (.96) during centers. These effect sizes do not reflect the larger effects observed if zero baselines were compared to the cause–effect toys and snack contexts.

Reciprocity and Balance of Communication

The total number of reciprocal exchanges between children with ASD and their trained peer partners roughly paralleled results for communicative acts. For Jaime, limited changes were noted in reciprocal exchanges during the centers intervention condition. His gains in reciprocity were observed primarily during activities with cause–effect toys (8.2 exchanges) and snack (7.8 exchanges). Similarly, Laney demonstrated few reciprocal exchanges during centers (1.8) and markedly higher reciprocal exchanges during cause–effect toys (9.3) and snack (16.7). Daniel also demonstrated limited changes in reciprocal exchanges in centers compared to baseline (1.2 and 1.0, respectively). The largest change noted in reciprocal exchanges between Daniel and his peer was during snack (9.8 exchanges).

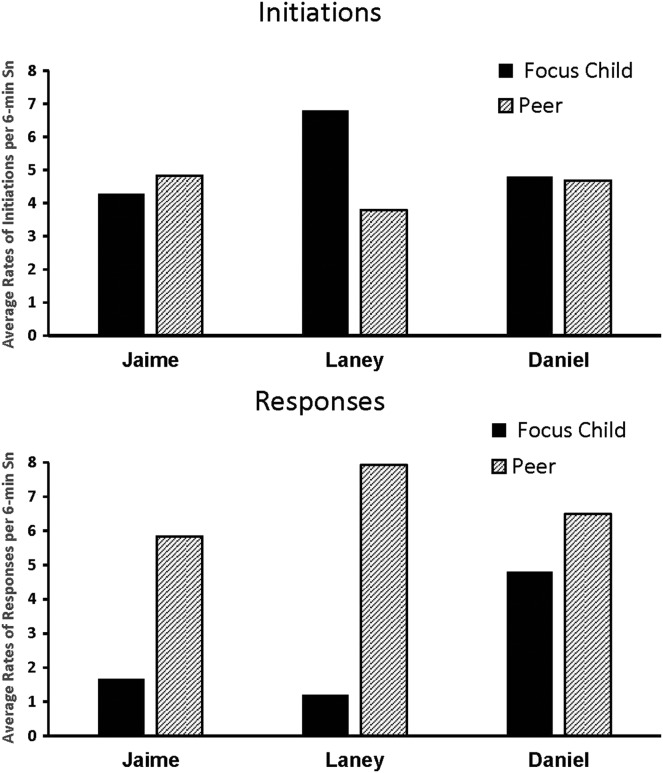

Figure 3 shows the breakdown of initiations and responses for the focus children and their peers. Similar mean rates of initiations per session are evident, with Laney initiating more than her peer. However, peers produced more responses than Jaime and Laney, whereas Daniel produced nearly as many responses as his peer. Thus, the overall balance in communicative acts was best for Daniel and his peer.

Figure 3.

Average rates of initiations and responses by children with autism spectrum disorder and trained peers during the peer-mediated speech-generating device intervention. Sn = session.

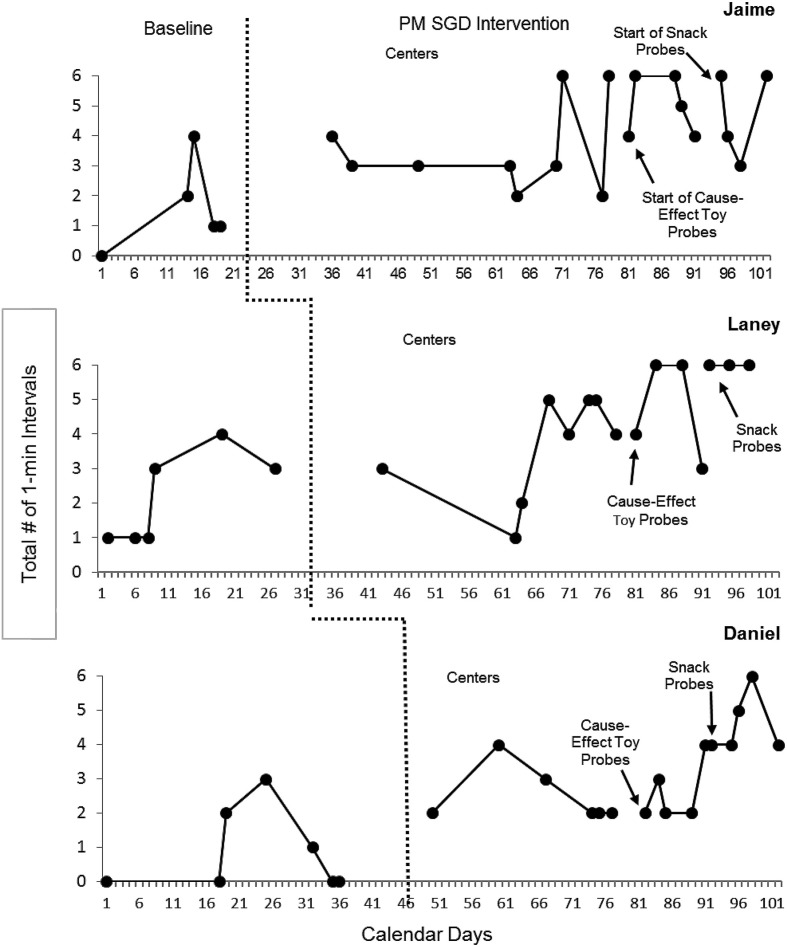

Engagement With Peers

Time engaged with a trained peer within the 6-min play activity is shown in Figure 4. In baseline, engagement was variable for all three children with ASD, ranging from zero to four intervals engaged. With the onset of the peer-mediated SGD intervention, Jaime demonstrated increased and more consistent levels of engagement with his peer, and his engagement continued to improve over the duration of the intervention. His engagement increased from an average of 1.6 intervals in baseline to an average of 4.2 intervals during intervention. Laney showed variable engagement, with amount engaged not much different than baseline (average of 2.2) for the first three intervention sessions; however, she maintained engagement of four to six intervals for 11 of the next 12 intervention sessions (average of 4.4 intervals). Daniel remained engaged with his peer for one interval on average in baseline; his engagement increased immediately with the start of the intervention, and he demonstrated more consistent engagement with an average of 3.2 intervals engaged over the course of the intervention.

Figure 4.

Total number of intervals of child engagement with peers during baseline and peer-mediated speech-generating device intervention. PM SGD = peer-mediated speech-generating device.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of combining peer training and SGD instruction on communication between preschool children with ASD and typically developing peers. Results indicate that typically developing preschool-age peers can be successfully taught to use the same SGD system as their classmates with ASD, with subsequent positive changes in initiations, responses, and reciprocal communication exchanges. These improvements seemed to generalize to additional classroom contexts, providing preliminary evidence of the potential benefits of varying the contexts for focus child–peer interaction.

All three children who participated in this study had severe ASD and showed no interest in interacting with peers at the start of the study. Similarly, peers did not approach or try to interact with these three children in the classroom. Combining an empirically supported PMI called Stay–Play–Talk (English, Goldstein, et al., 1997; Goldstein et al., 1997) with direct instruction on use of an SGD (GoTalk 4+) provided opportunities for the children to learn to communicate with each other during typical classroom activities. Compared to baseline observations, moderate effects on rates of peer-directed communication were evident for all three children with ASD. Meanwhile, larger effects were observed in spontaneous communication for the three trained peers. These results demonstrate the viability of integrating these two intervention approaches. But the smaller effects for the children with ASD seemed to reflect room for improvement.

One interesting and positive outcome of the study was a marked increase in initiations for all three participants with ASD. It is rather surprising to find children with ASD, such as Daniel, initiating more than a peer partner, as initiations are typically a weakness in children with ASD, especially when interacting with peers (Hauck, Fein, Waterhouse, & Feinstein, 1995; Stone & Caro-Martinez, 1990). In the current study, reporting observational data for both children with ASD and communication behaviors of trained peer partners allowed for comparison of the type of acts expressed within each dyad. For example, all six participants increased their initiations and responses, but Jaime and Laney lagged in their improvements in responding. This is not typical of most PMIs and may reflect a difference in the SGD mode of communication. In addition, results showed that all three children with ASD increased in their ability to participate in back-and-forth social and/or communication exchanges with the peers. In the PECS and Pals study, Thiemann-Bourque et al. (2016) reported marked increases primarily in initiations for four preschoolers with ASD and changes primarily in responses for the trained peers. Training peers to use an SGD may allow for more balanced communication exchanges for the following reasons. First, the peer partner would not be placed in the position of “responder” as would be the case when using PECS, given that PECS training focuses on the child learning to request and receive preferred items from a peer. Second, when the peer is responsible for taking the picture symbol from the child and then placing it back in the correct position on the PECS binder, these actions often ended the exchange and thus interfered with the naturalness of back-and-forth communication. Using the GoTalk 4+, both the children with ASD and the trained peer had access to the same symbols and could activate them quickly to either initiate or respond. Another advantage an SGD may have over other AAC systems is that the messages are more easily understood by others (van der Meer & Rispoli, 2010).

Specific to AAC interventions for children with developmental disabilities, Lancioni et al. (2007) noted the need to report on individual child performance and to provide greater details on specific teaching procedures. Of the few studies available to date examining approaches to include peers as communication partners in SGD interventions, specific procedures for how peers were trained and fidelity measures are absent or vague (Schwartz, Garfinkle, & Bauer, 1998; Trembath et al., 2009; Trottier et al., 2011). The outcomes of the current study add to current AAC interventions literature for young children in two important ways. First, we report on multiple child outcomes in relation to communication behaviors (initiations and responses), the mode of communication (SGD, gestures, speech), the function expressed, reciprocal exchanges with peers, and the duration of engagement. In addition, we also reported changes in peer communication behaviors, an outcome too often absent in AAC intervention literature. Last, we provide detailed information on the time frame and setting for training peers, specific peer-mediated instructional strategies, and fidelity steps for classroom group implementation. As peer-mediated AAC intervention research grows, it will be essential for researchers to continue to provide detailed teaching procedures along with evaluation of improvements across different inclusive contexts.

Analyses of Additional Social Contexts

The notable improvements in rates of communication with the introduction of preferred cause–effect toys and snack contexts add preliminary data to the relatively sparse research examining how implementing interventions within different contexts of inclusive environments may yield varied outcomes (Thiemann-Bourque et al., 2016). These results are preliminary because these contexts were not included in baseline observations nor was their introduction staggered in a multiple baseline fashion. Additional research is needed to determine why these contexts produced more robust intervention effects and to replicate contextual effects in an experimentally rigorous manner. Possibly, children showed marked increases in communication in these contexts, because they had higher levels of interest and motivation to use the SGD to obtain a more immediate or stronger reinforcer. Perhaps the provision of additional models of SGD use for reciprocal communication by peers afforded sufficient opportunities for the children with autism to observe and learn from these models. It has been suggested that peers can become natural discriminative stimuli for positive interactions and thus may be more effective than adults at teaching children age-appropriate skills (Pierce & Schreibman, 1997). Alternatively, this could be a novelty effect or simply could have offered variety that overcame routine responding ingrained after many baseline and intervention sessions.

Clinical Implications

In an effort to create an ideal environment for improving social communication between preschool children learning to use AAC and typically developing peers, we need to recognize how the setting or social context may influence child behavior. Thiemann-Bourque and colleagues (2016) noted greater communication and more consistent engagement during snack for two children with ASD. The authors suggested that, for some children, preferred or more motivating activities such as snack may create a greater desire initially to communicate with peers. Preliminary outcomes of the current study demonstrate similar findings in that two children showed pronounced improvements when given preferred cause–effect toys and all children engaged in more communication with peers during snack. Schepis et al. (1998) reported similar rates of communication across snack and play time (i.e., three to four per min) with adult communication partners. Additional research is needed to examine the impact of peer-mediated AAC teaching strategies within varied social contexts. For the time being, our results suggest that early intervention teams working with young children with ASD who are learning to use AAC should consider training peers to use the same AAC system and begin in contexts that are reinforcing and motivating. Our outcomes demonstrate the feasibility of successfully training peers facilitative social skills and how to use an SGD within 90 min, an improvement from our prior study in which training peers to use PECS took approximately 2–3 hr (Thiemann-Bourque et al., 2016).

Limitations

One limitation of the study was the limited staggering of the length of the baseline condition. This was in part due to child absences and less than optimal spread in the probing of baseline performance. However, the seriousness of this limitation is minimized by the finding of zero baselines for all participants over five to seven baseline data points over a 19- to 36-day period. Furthermore, the adding of two conditions to the intervention phase (preferred cause–effect toys and snack contexts) was not evaluated within an experimental design. Nevertheless, these surprisingly strong preliminary data identified variations in the intervention condition worthy of further investigation. These preliminary data also provided an assessment of generalization of gains across contexts. Given the late start in the school year, we were unable to examine generalized skill use to new communication partners or settings outside the classroom or maintenance of gains postintervention. Finally, AAC interventions for children with ASD and complex communication needs to date have narrowly focused on basic communication skills such as requesting to have personal needs met. Outcomes of this study revealed higher increases in requesting skills and limited changes in comments, shares, and gaining a peer's attention. If time allowed, the study could have been improved by lengthening the duration of the intervention and modifying the intervention to impact a wider range of communication skills.

Conclusions

Williams, Krezman, and McNaughton (2008) adeptly summarized principles to guide the future for individuals who use AAC in stating that AAC is “…a collection of techniques and strategies meant to support participation in a wide range of communication activities in a wide range of social and physical environments, each with its own unique challenges and demands” (p. 197). In a short time, we taught peers without disabilities to be responsive communication partners to preschool children with ASD who did not interact in inclusive classroom activities. The AAC intervention led to improved communication, reciprocity, and engagement in routine preschool social settings for both peers and children with ASD. Additional AAC intervention research is needed that includes a larger number of children, examines or compares different AAC interventions, and explores specific peer characteristics that may impact child outcomes. There is also a significant need to determine effective AAC teaching strategies that moves beyond teaching requesting skills and will improve a range of functional communication skills. Children who have larger communication repertoires will have greater opportunities to interact with peers and others in a wider variety of social settings. Finally, Light and McNaughton (2012) noted how times have changed over the past 20–30 years in relation to positive outcomes of AAC interventions. They discuss the explosion of mobile technologies and multifunction devices such as touch-screen phones and iPads with a variety of apps to support communication. As the field of AAC intervention progresses, the need for examining use of these new mobile technologies and devices within PMIs is evident.

Acknowledgments

The research was funded by a grant awarded to K. S. Thiemann-Bourque through the Friends of the Life Span Institute at the University of Kansas and partially supported by Grant 1R01DC012530 awarded to Dr. Kathy S. Thiemann-Bourque through National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. We gratefully acknowledge the classroom teacher Debbie Wulf-Walter for her cooperation and efforts in helping make the project a success and the participating families for their time and support.

Funding Statement

The research was funded by a grant awarded to K. S. Thiemann-Bourque through the Friends of the Life Span Institute at the University of Kansas and partially supported by Grant 1R01DC012530 awarded to Dr. Kathy S. Thiemann-Bourque through National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

References

- Boardmaker. (2014). [Computer software]. Pittsburg, PA: Mayer-Johnson. [Google Scholar]

- Bock S. J., Stoner J. B., Beck A. R., Hanley L., & Prochnow J. (2005). Increasing functional communication in non-speaking preschool children: Comparison of PECS and VOCA. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 40, 264–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bondy A., & Frost L. (1994). The picture exchange communication system. Focus on Autistic Behavior, 9, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brady N. (2000). Improved comprehension of object names following voice output communication aid use: Two case studies. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 16(3), 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Chan J. M., Lang R., Rispoli M., O'Reilly M., Sigafoos J., & Cole H. (2009). Use of peer-mediated interventions in the treatment of autism spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(4), 876–889. [Google Scholar]

- English K., Goldstein H., Shafer K., & Kaczmarek L. (1997). Promoting interactions among preschoolers with and without disabilities: Effects of a buddy skills-training program. Exceptional Children, 63(2), 229–243. [Google Scholar]

- English K., Shafer K., Goldstein H., & Kaczmarek L. (1997). Teaching buddy skills to preschoolers. Innovations: American Association on Mental Retardation, Research to Practice Series, 9, 2–46. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman S. F., Gulsrud A., & Kasari C. (2015). Brief report: Linking early joint attention and play abilities to later reports of friendships for children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(7), 2259–2266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkle A. N., & Schwartz I. S. (2002). Peer imitation increasing social interactions in children with autism and other developmental disabilities in inclusive preschool classrooms. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 22(1), 26–38. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H., English K., Shafer K., & Kaczmarek L. (1997). Interaction among preschoolers with and without disabilities: Effects of across-the-day peer intervention. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 40(1), 33–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H., Lackey K. C., & Schneider N. J. B. (2014). A new framework for systematic reviews: Application to social skills interventions for preschoolers with autism. Exceptional Children, 80(3), 262–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0014402914522423 [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein H., Schneider N., & Thiemann K. (2007). Peer-mediated social communication intervention: When clinical expertise informs treatment development and evaluation. Topics in Language Disorders, 27(2), 182–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hauck M., Fein D., Waterhouse L., & Feinstein C. (1995). Social initiations by autistic children to adults and other children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25(6), 579–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner R., Carr E., Halle J., McGee G., Odom S., & Wolery M. (2005). The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 165–179. [Google Scholar]

- Horner R. D., & Baer D. M. (1978). Multiple-probe technique: A variation on the multiple baseline. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 11(1), 189–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasari C., Kaiser A., Goods K., Nietfeld J., Mathy P., Landa R., & Almirall D. (2014). Communication interventions for minimally verbal children with ASD: A sequential multiple assignment randomized trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 53(6), 635–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koegel L. K. (1995). Communication and language intervention. In Koegel R. L. & Koegel L. K. (Eds.), Teaching children with autism: Strategies for initiating positive interactions and improving learning opportunities (pp. 17–32). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Koegel R. L., O'Dell M. C., & Koegel L. K. (1987). A natural language teaching paradigm for nonverbal autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 17, 187–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancioni G. E., O'Reilly M. F., Cuvo A. J., Singh N. N., Sigafoos J., & Didden R. (2007). PECS and VOCAs to enable students with developmental disabilities to make requests: An overview of the literature. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 28(5), 468–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J., & McNaughton D. (2012). The changing face of augmentative and alternative communication: Past, present, and future challenges. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 28(4), 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Autism Center. (2015). Findings and conclusions: National Standards Project, Phase 2. Randolph, MA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Odom S. L., McConnell S. R., Ostrosky M., Peterson C., Skellenger A., Spicuzza R., Chandler L., … McEvoy M. A. (1997). Play time/social time: Organizing your classroom to build interaction skills. Minneapolis, MN: Institute on Community Integration (UIAP), University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Olive M. L., de la Cruz B., Davis T. N., Chan J. M., Lang R. B., O'Reilly M. F., & Dickson S. M. (2007). The effects of enhanced milieu teaching and a voice output communication aid on the requesting of three children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(8), 1505–1513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R. I., Vannest K. J., Davis J. L., & Sauber S. B. (2011). Combining nonoverlap and trend for single-case research: Tau-U. Behavior Therapy, 42(2), 284–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierce K., & Schreibman L. (1997). Multiple peer use of pivotal response training to increase social behaviors of classmates with autism: Results from trained and untrained peers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30(1), 157–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichow B., & Volkmar F. R. (2010). Social skills interventions for individuals with autism: Evaluation for evidence-based practices within a best evidence synthesis framework. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 149–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romski M., Sevcik R. A., Adamson L. B., Cheslock M., Smith A., Barker R. M., & Bakeman R. (2010). Randomized comparison of augmented and nonaugmented language interventions for toddlers with developmental delays and their parents. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53(2), 350–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romski M., Sevcik R. A., Barton-Hulsey A., & Whitmore A. S. (2015). Early intervention and AAC: What a difference 30 years makes. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31(3), 181–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis M. M., Reid D. H., Behrmann M., & Sutton K. A. (1998). Increasing communicative interactions of young children with ASD using a voice output communication aid and naturalistic teaching. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 31(4), 561–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlosser R. W., Sigafoos J., & Koul R. K. (2009). Speech output and speech generating devices in autism spectrum disorders. In Mirenda P. & Iacono T. (Eds.), Autism Spectrum Disorders and AAC (pp. 141–170). Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz I. S., Garfinkle A. N., & Bauer J. (1998). The picture exchange communication system: Communicative outcomes for young children with disabilities. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 18, 144–159. [Google Scholar]

- Sevcik R. A., Barton-Hulsey A., & Romski M. A. (2008, May). Early intervention, AAC, and transition to school for young children with significant spoken communication disorders and their families. Seminars in Speech and Language, 29(02), 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigman M., Ruskin E., Arbelle S., Corona R., Dissanayake C., Espinosa M., & Robinson B. F. (1999). Continuity and change in the social competence of children with autism, Down syndrome, and developmental delays. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 64, 1–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone W. L., & Caro-Martinez L. M. (1990). Naturalistic observations of spontaneous communication in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20(4), 437–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann-Bourque K., Brady N., McGuff S., Stump K., & Naylor A. (2016). Picture exchange communication system and pals: A peer-mediated augmentative and alternative communication intervention for minimally verbal preschoolers with autism. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 59(5), 1133–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiemann K. S., & Goldstein H. (2004). Effects of peer training and written text cueing on social communication of school-age children with pervasive developmental disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 47(1), 126–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trembath D., Balandin S., Togher L., & Stancliffe R. J. (2009). Peer-mediated teaching and augmentative and alternative communication for preschool-aged children with ASD. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 34(2), 173–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trottier N., Kamp L., & Mirenda P. (2011). Effects of peer-mediated instruction to teach use of speech-generating devices to students with autism in social game routines. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 27(1), 26–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Meer L. A., & Rispoli M. (2010). Communication interventions involving speech-generating devices for children with ASD: A review of the literature. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 13(4), 294–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. B., Krezman C., & McNaughton D. (2008). “Reach for the stars”: Five principles for the next 25 years of AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24(3), 194–206. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman I. L., Steiner V. G., & Pond R. E. (2002). Preschool Language Scale–Fourth Edition (PLS-4). San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]