Abstract

Background

Unexplained chronic cough (UCC) causes significant impairments in quality of life. Effective assessment and treatment approaches are needed for UCC.

Methods

This systematic review of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) asked: What is the efficacy of treatment compared with usual care for cough severity, cough frequency, and cough-related quality of life in patients with UCC? Studies of adults and adolescents aged > 12 years with a chronic cough of > 8 weeks’ duration that was unexplained after systematic investigation and treatment were included and assessed for relevance and quality. Based on the systematic review, guideline suggestions were developed and voted on by using the American College of Chest Physicians organization methodology.

Results

Eleven RCTs and five systematic reviews were included. The 11 RCTs reported data on 570 participants with chronic cough who received a variety of interventions. Study quality was high in 10 RCTs. The studies used an assortment of descriptors and assessments to identify UCC. Although gabapentin and morphine exhibited positive effects on cough-related quality of life, only gabapentin was supported as a treatment recommendation. Studies of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) were affected by intervention fidelity bias; when this factor was addressed, ICS were found to be ineffective for UCC. Esomeprazole was ineffective for UCC without features of gastroesophageal acid reflux. Studies addressing nonacid gastroesophageal reflux disease were not identified. A multimodality speech pathology intervention improved cough severity.

Conclusions

The evidence supporting the diagnosis and management of UCC is limited. UCC requires further study to establish agreed terminology and the optimal methods of investigation using established criteria for intervention fidelity. Speech pathology-based cough suppression is suggested as a treatment option for UCC. This guideline presents suggestions for diagnosis and treatment based on the best available evidence and identifies gaps in our knowledge as well as areas for future research.

Key Words: chronic cough, cough frequency and severity, cough-related quality of life, treatment, unexplained cough

Abbreviations: BHR, bronchial hyperresponsiveness; CHEST, American College of Chest Physicians; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; PNDS, postnasal drip syndrome; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TRPV1, type 1 transient receptor potential vanilloid; UCC, unexplained chronic cough

Summary of Recommendations and Suggestions

1. In adult patients with chronic cough, we suggest that unexplained chronic cough be defined as a cough that persists longer than 8 weeks, and remains unexplained after investigation, and supervised therapeutic trial(s) conducted according to published best-practice guidelines (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

2. In adult patients with chronic cough, we suggest that patients with chronic cough undergo a guideline/protocol based assessment process that includes objective testing for bronchial hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilic bronchitis, or a therapeutic corticosteroid trial (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

3. In adult patients with unexplained chronic cough, we suggest a therapeutic trial of multimodality speech pathology therapy (Grade 2C).

4. In adult patients with unexplained chronic cough and negative tests for bronchial hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilia (sputum eosinophils, exhaled nitric oxide), we suggest that inhaled corticosteroids not be prescribed (Grade 2B).

5. In adult patients with unexplained chronic cough, we suggest a therapeutic trial of gabapentin as long as the potential side effects and the risk-benefit profile are discussed with patients before use of the medication, and there is a reassessment of the risk-benefit profile at 6 months before continuing the drug (Grade 2C).

Remarks: Because health-related quality of life of some patients can be so adversely impacted by their unexplained chronic cough, and because gabapentin has been associated with improvement in quality of life in a randomized controlled clinical trial, the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Cough Expert Panel believes that the potential benefits in some patients outweigh the potential side effects. With respect to dosing, patients without contraindications to gabapentin can be prescribed a dose escalation schedule beginning at 300 mg once a day with additional doses being added each day as tolerated up to a maximum tolerable daily dose of 1,800 mg a day in two divided doses.

6. In adult patients with unexplained chronic cough and a negative workup for acid gastroesophageal reflux disease, we suggest that proton pump inhibitor therapy not be prescribed (Grade 2C).

Persistent cough of unexplained origin1 is a significant health issue that occurs in up to 5% to 10% of patients seeking medical assistance for a chronic cough2 and from 0% to 46% of patients referred to specialty cough clinics.3, 4, 5, 6 Patients with unexplained chronic cough (UCC) experience significant impairments in quality of life. They endure a chronic cough that persists, often for many months or years, despite systematic investigation and treatment of known causes. There is a need to identify effective treatment approaches for UCC. In addition, it is essential to distinguish the cough experienced by these patients from cough that can be explained and effectively treated5 because incomplete investigation or inadequate treatment will also result in a persistent cough that seems to be unexplained.

UCC represents a clinically significant chronic cough that persists despite appropriate investigation and treatment. It can occur under three different circumstances: (1) chronic cough with no diagnosable cause (UCC), (2) explained but refractory chronic cough, and (3) unexplained and refractory chronic cough. When patients with chronic cough undergo investigation and the results of these investigations do not identify a cause of their cough, this condition is termed UCC. Patients can be assessed, investigated, and identified as having conditions that are known to be associated with chronic cough, but the cough persists after treatment of these conditions, indicating explained but refractory chronic cough. Patients may have negative investigations for chronic cough and undergo empiric therapy trials, and if these are negative, the patient has unexplained refractory chronic cough. It is unclear whether these distinctions are either useful or necessary.

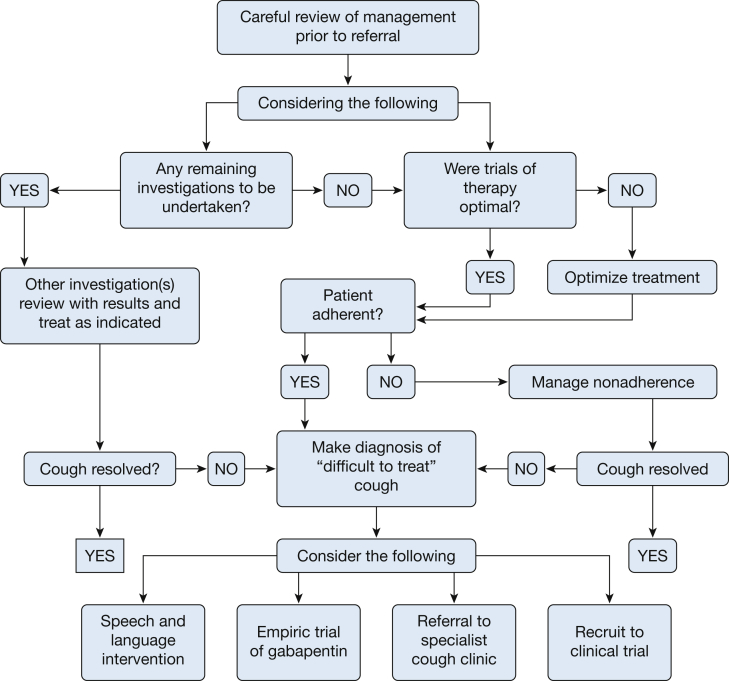

The most useful assessment may be to identify UCC by using the algorithm shown in Figure 1. UCC can be defined according to several distinct features. These are: (1) a chronic cough that persists after investigation and follow-up, and (2) that persists after therapeutic trials have been conducted according to indications identified during assessment and which have been conducted according to published best practice guidelines in an adherent patient. The present systematic review addresses the problem of UCC in the areas of diagnosis, management, and future directions.

Figure 1.

A proposed algorithm detailing a management approach to the patient with “difficult-to-treat” cough.5

Methods

The methodology of the CHEST Guideline Oversight Committee was used to select the Expert Cough Panel chair and the international panel of experts to perform the systematic review, synthesis of the evidence, and development of the recommendations and suggestions.7

Systematic Review Question

The clinical question for this systematic review was generated by using the PICO (population, intervention, comparison, outcome) format.8 The review question was: What is the efficacy of treatment compared with usual care for cough severity, cough frequency, and cough-related quality of life in patients with UCC?

Literature Search

The methods used for this systematic review conformed with those outlined in the article “Methodologies for the development of CHEST guidelines and expert panel reports.”7 The National Guideline Clearinghouse (www.guideline.gov) and the Guidelines International Network Library (www.g-i-n.net) were searched for existing guidelines on UCC. Systematic reviews and clinical trials were identified from searches of electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials [Cochrane Library]) commencing from the earliest available date until April 2014. The reference lists of retrieved articles were examined for additional citations. The search terms used were: [Cough OR chronic cough] AND [Idiopathic OR refractory OR unexplained OR intractable]. An additional search for chronic cough and [clinical trial] was conducted in PubMed.

The titles and abstracts of the search results were independently evaluated by two reviewers (P.G.G. and W.G.) to identify potentially relevant articles, based on the eligibility criteria of the study design (randomized controlled trial [RCT], controlled clinical trial, or systematic review) and population (patients with chronic cough that was unexplained, refractory to treatment, or idiopathic; in adults or adolescents aged > 12 years) (Table 1). The full text of all potentially relevant articles was retrieved, and two reviewers (W.G. and P.G.G.) independently evaluated all the retrieved studies against the criteria.

Table 1.

Eligibility Criteria

| Criteria | Study Requirements |

|---|---|

| Inclusion | English-language publication |

| Population | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Intervention | Treatment: any pharmacologic or nonpharmacologic intervention |

| Comparison/control | Randomized controlled trial or controlled clinical trial or a systematic review |

| Outcome | Cough severity or frequency or quality of life |

ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Quality Assessment

Included articles underwent methodologic assessment. For RCTs and controlled clinical trials, quality assessment was conducted by using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.9 For systematic reviews, the Documentation and Appraisal Review Tool was used.10

Grading Recommendations

In addition to the quality of the evidence, the recommendation grading includes a strength of recommendation dimension, which is used for all CHEST guidelines.7 In the context of practice recommendations, a strong recommendation applies to almost all patients, whereas a weak recommendation is conditional and applies only to some patients. In the context of research recommendations (eg, those provided in the present guideline), we intended for a strong recommendation (Grade 1) to imply that we recommend using intervention fidelity strategies in all studies in which patients with chronic cough are being diagnosed and managed. Intervention fidelity has been identified as an important aspect of chronic cough studies and is defined “as the extent to which an intervention was delivered as conceived and planned-to arrive at valid conclusions concerning its effectiveness in achieving target outcomes.”11 The strength of recommendation here is based on consideration of three factors: balance of benefits to harms, patient values and preferences, and resource considerations. Harms incorporate risks and burdens to the patients, which can include convenience or lack of convenience, difficulty of administration, and invasiveness. These variables, in turn, affect patient preferences. The resource considerations extend beyond economics and should also factor in time and other indirect costs. The authors of these recommendations have considered these parameters in determining the strength of the recommendations and associated grades.

The findings of this systematic review were used to support the evidence-graded recommendations or suggestions. A highly structured consensus-based Delphi approach was used to provide expert advice on all guidance statements. The total number of eligible voters for each guidance statement varied based on the number of managed individuals recused from voting on any particular statements because of their potential conflicts of interest (e-Table 1). Transparency of process was documented. Further details of the methods related to conflicts of interests and transparency have been published elsewhere.7

Results

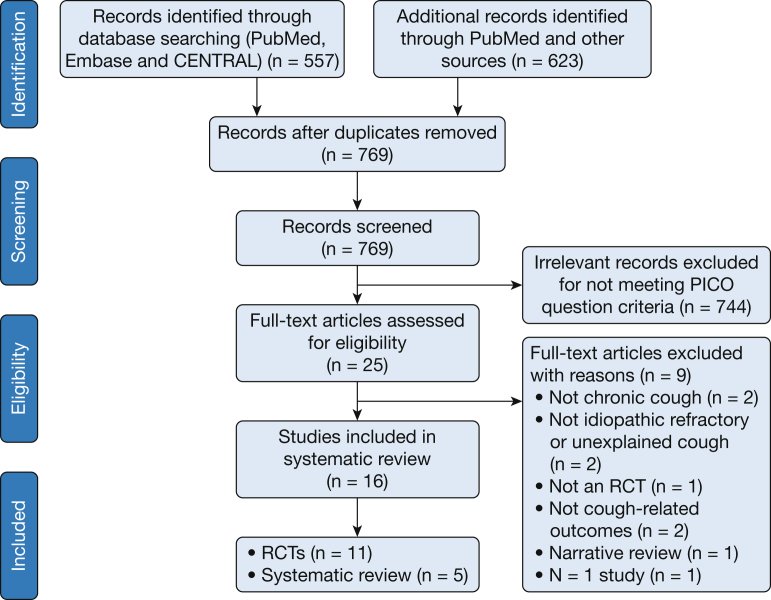

Figure 2 presents the results of the systematic review. Nineteen individual RCTs were identified; 11 met the inclusion criteria, and eight were excluded. Reasons for exclusion were: studies did not assess chronic cough because cough duration < 8 weeks,12, 13, 14 the study topic was not idiopathic/refractory or unexplained cough,15, 16 the study was not an RCT,17 and there were no cough-related outcomes.18 The study by Sher et al19 used memantine as an intervention and met inclusion criteria, but no results were reported. A single-patient RCT (one study) of ibuprofen was not included.20

Figure 2.

Systematic review flow diagram. Review Manager (RevMan) computer program. CENTRAL = Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; PICO = population, intervention, comparison, outcome; RCT = randomized controlled trial.

Six potentially relevant systematic reviews were identified; five met the inclusion criteria, and one was excluded because it was a narrative review.21 No relevant guidelines were identified. This technique resulted in the inclusion of five systematic reviews and 11 RCTs, which assessed a variety of interventions for UCC, refractory cough, or idiopathic cough (Table 2).

Table 2.

Study Characteristics: Extraction From Chronic Refractory Cough of CHEST

| Citation | Study Design | Intervention |

Placebo |

Duration | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antitussive Interventions | No. | No. | Age, y | |||

| Khalid et al,24 2014 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial | TRPV1 600 mg | 21 | 21 | 53 | A single dose |

| Ryan et al,34 2012 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Gabapentin 1,800 mg qd | 32 | 30 | 60.9 ± 12.9a | 10 wk |

| Shaheen et al,36 2011 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Esomeprazole 40 mg bid | 22 | 18 | 51.0 ± 11.6a | 12 wk |

| Yousaf et al,35 2010 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Erythromycin 250 mg qd | 15 | 15 | 61 ± 9a | 12 wk |

| Rytila et al,27 2008 | Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Mometasone furoate 400 μg once daily | 70 | 70 | 47 ± 11a | 8 wk |

| Morice et al,25 2007 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial | Morphine sulfate, 5 mg bid | NA | NA | NA | 4 wk |

| Ribeiro et al,29 2007 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Metered-dose inhaler, chlorofluorocarbon-beclomethasone (1,500 μg/d), 500 μg tid | 44 | 20 | 50 ± 18a | 2 wk |

| Vertigan et al,23 2006 | Randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled trial | SPEICH-C. Participants in each group attended 4 individual 30-min intervention sessions scheduled over a 2-mo period, and home practice of the components of SPEICH-C was recommended | 43 | 44 | NA | 8 wk |

| Jeyakumar et al,22 2006 | Randomized, placebo-controlled trial | Amitriptyline 10 mg qn | 28 | 13 | 49.7b | 10 d |

| Pizzichini et al,39 1999 | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Budesonide Turbuhaler 400 μg/inhalation bid | 25 | 25 | 43 (20-75)c | 2 wk |

| Holmes et al,26 1992 | Randomized crossover controlled trial | Ipratropium bromide 320 μg/d | 14 | 14 | 47 ± 12a | 3 wk |

CHEST = American College of Chest Physicians; NA = outcome not assessed; SPEICH-C = Speech Pathology Evaluation and Intervention for Chronic cough; TRPV1 = type 1 transient receptor potential vanilloid.

Mean ± SD.

Median.

Median (range).

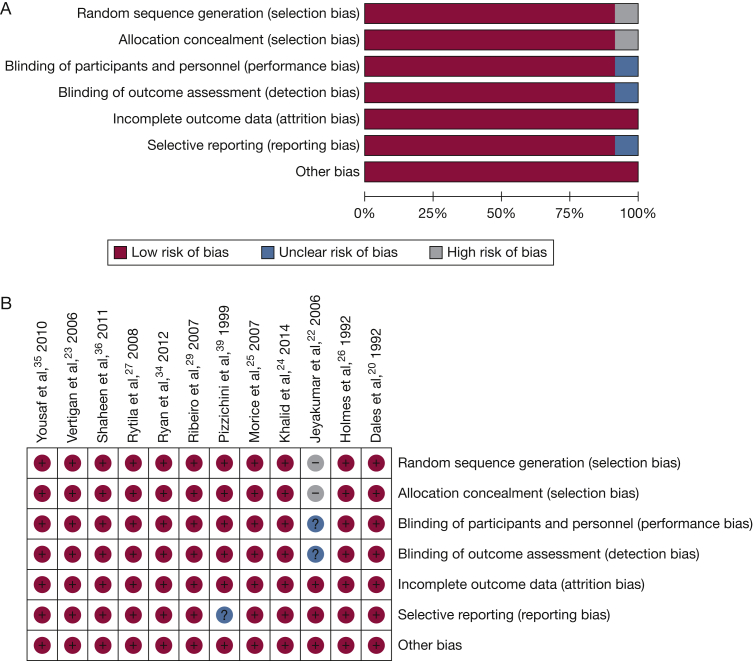

Study Quality

The study quality for RCTs and controlled clinical trials was high in 10 studies (Figs 3A and 3B). Significant risk of bias was identified in one study22 in the areas of randomization, concealment of allocation, blinding of the intervention and outcome assessments, and measurement the quality of life outcome. The intervention used in the study by Vertigan et al23 was a speech pathology intervention and involved concealed random allocation, but treatment group and outcome assessments were unblinded.

Figure 3.

A, Quality assessment for included RCTs, overall results. Version 5.2. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012. B, Quality assessment for included RCTs, individual study results. Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.2. Computer program. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2012. See Figure 2 legend for expansion of abbreviation.

For systematic reviews, the Documentation and Appraisal Review Tool10 (Table 3) was used. Each of the systematic reviews demonstrated substantial adherence to the quality assessment criteria.

Table 3.

Quality Assessment for Included Systematic Reviews

| Item | Yancy et al,31 2013 (A) | Johnstone et al,33 2013 | Chamberlain et al,30 2014 | Cohen and Misono,32 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Did the authors develop the research question(s) and inclusion/exclusion criteria before conducting the review? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2. Did the authors describe the search methods used to find evidence (original research) on the primary question(s)? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3. Was the search for the evidence reasonably comprehensive? Were the following included? | ||||

| a. Search included at least two electronic sources | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| b. Authors chose the most applicable electronic databases (eg, CINAHL for nursing journals, Embase for pharmaceutical journals, and MEDLINE for general, comprehensive search) and only limited search by date when performing an update of a previous systematic review | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| c. Search methods are likely to capture all relevant studies (eg, includes languages other than English; gray literature such as conference proceedings, dissertations, theses, clinical trials registries, and other reports) and authors’ hand-searched journals or reference lists to identify published studies, which were not electronically available | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4. Did the authors do the following when selecting studies for the review? | ||||

| a. Provide in the inclusion criteria: population, intervention, outcome, and study design? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| b. State whether > 1 person applied the selection criteria independently? | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| c. State how disagreements were resolved during study selection? | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| d. Provide a flowchart or descriptive summary of the included and excluded studies? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| e. Include all study designs appropriate for the research questions posed? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5. Were the characteristics of the included studies provided in an aggregated form such as a table? Were data from the original studies provided on the participants, interventions and outcomes? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Characteristics of Included Studies

Most (n = 9) trials were parallel-group, single-center studies. There were three crossover trials24, 25, 26 and one multicenter trial.27 The 11 RCTs reported data on 567 participants with UCC. Study sample size ranged from 14 to 144 subjects, with an average of 47 subjects per study. Participants had a mean age of 52.1 years, and most (60%) were women. Cough lasted a mean of 32 months prior to study entry.

Diagnosis of UCC

The diagnosis of UCC is applied after completion of a systematic assessment and treatment for known causes of cough. This analysis found that a variety of terms and descriptions were used to identify the patient with UCC. It is likely that most studies assessed patients adequately for the common causes of chronic cough (asthma, gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD], rhinosinusitis, and nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis), but documentation of this assessment was limited (Tables 4 and 5).28

Table 4.

Flowchart for Screening Chronic Unexplained, Refractory/Intractable, or Idiopathic Cough in Included Studies

| Study | Investigations |

Exclusions of Diseases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No Smoking | ACEI | Chest Imaging | Sinus Imaging | BPC | Induced Sputum | Bronchoscopy | Esophageal pH | ||

| Khalid et al,24 2014 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | NA |

| Ryan et al,34 2012 | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | COPD, asthma, respiratory infection |

| Shaheen et al,36a 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Aerodigestive malignancy or Barrett’s oesophagus, upper respiratory infection |

| Yousaf et al,35 2010 | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Asthma, EB, bronchiectasis, chronic lung disease, GERD, UACS |

| Rytila et al,27 2008 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | COPD, asthma, upper respiratory infection, UACS, GERD |

| Morice et al,25 2007 | Yesb | Yesb | Yesb | Yesb | Yesb | No | Yesb | Yesb | NA |

| Ribeiro et al,29 2007 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | GERD, respiratory infection, asthma, COPD, rhinosinusitis, UACS |

| Vertigan et al,23 2006 | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Upper respiratory tract infection, allergy, UACS, asthma, GERD, EB, lung pathology, COPD, neurologic voice disorder |

| Jeyakumar et al,22 2006 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Asthma |

| Pizzichini et al,39 1999 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Respiratory tract infection, chronic bronchitis, sinusitis, asthma |

| Holmes et al,26 1992 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Asthma, GERD |

BPC = bronchial provocation challenge; EB = eosinophilic bronchitis; UACS = upper airway cough syndrome. See Table 1 and 2 legends for expansion of other abbreviations.

Inhaled or oral corticosteroids were prescribed although nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis/asthma were not indicated in the study.

Based on the previously published probability-based treatment algorithm.28

Table 5.

Flowchart for Screening Chronic Unexplained, Refractory/Intractable, or Idiopathic Cough in Included Studies

| Study | Failure to Improve With Empiric Treatment |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UACS | Nasal Disease | Asthma | NAEB | GERD | |

| Khalid et al,24 2014 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ryan et al,34 2012 | No | Yes | Yes | Yesa | Yes |

| Shaheen et al,36 2011 | Yes | Yes | Yesa | Yesa | Yes |

| Yousaf et al,35 2010 | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Rytila et al,27 2008 | No | No | No | No | No |

| Morice et al,25 2007 | Yesb | Yesb | Yesb | Yesb | Yesb |

| Ribeiro et al,29 2007 | No | No | No | No | No |

| Vertigan et al,23 2006 | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Jeyakumar et al,22 2006 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Pizzichini et al,39 1999 | Yes | No | No | No | Yes |

| Holmes et al,26 1992 | No | No | No | No | No |

UCC Terminology

Although UCC was identified as an inclusion criterion for each study, the studies used a variety of descriptions and labels to make a diagnosis of UCC (Table 6). The title, abstract, introduction, and conclusion were examined for descriptors used for this condition. Eight of the RCTs used a simple label to identify the patient group, whereas three studies did not use a label but provided a descriptive phrase.23, 27, 29 One study used several labels concurrently within the same article25 (treatment-resistant, idiopathic, and intractable). The systematic reviews used the terms refractory,30, 31, 32 unexplained,31, 33 and idiopathic cough.32

Table 6.

Labels Used to Describe Chronic Unexplained Cough

| Label | Reference | |

|---|---|---|

| Unexplained chronic cough | 2 studies26, 35 | 2 SR31, 33 |

| Refractory chronic cough | 2 studies24, 34 | 3 SR30, 31, 32 |

| Idiopathic chronic cough | 1 study20, 25 | 1 SR32 |

| Chronic cough of unknown etiology | 3 studies26, 36, 37 | |

| Chronic treatment-resistant cough | 1 study25 | |

| Intractable chronic cough | 1 study25 | |

| Postviral vagal neuropathy | 1 study22 | |

SR = systematic review.

The labels and descriptions identified UCC as either refractory to empiric treatment trials23, 24, 25, 30, 31, 32, 34 or as unable to be assigned an etiology.20, 25, 29, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36 The case descriptions used were as follows: Vertigan et al,23 chronic cough that had persisted despite medical treatment according to the anatomic diagnostic protocol; Rytila et al,27 cough and symptoms suggesting asthma but with normal lung function; Jeyakumar et al,22 history consistent with postviral vagal neuropathy, which includes a daily, dry, nonproductive cough of 6 months’ duration precipitated by a throat tickle, dry sensation, laughter, or speaking (most patients had a history of a readily identifiable antecedent upper respiratory tract infection); and Ribeiro et al,29 chronic cough for which GERD and postnasal drip syndrome (PNDS) had been excluded.

Intervention Fidelity Assessment

None of the RCTs reported application of the CHEST 2006 clinical practice guidelines in their standardized assessment of potential participants. Three RCTs reported that the patients were assessed according to a standardized published assessment protocol (Vertigan et al,23 CHEST 2006; Irwin et al,2 CHEST 2006; Yousaf et al,35 British Thoracic Society guidelines; Morice et al,25 algorithm from European Respiratory Journal).

Each of the RCTs reported that patients were excluded if they were assessed as having comorbidity associated with cough. Asthma was excluded by physician diagnosis (nine trials), treatment use for asthma (one trial), or negative asthma treatment trial (one study). Significant smoking (> 10 pack-years) was an exclusion criterion in nine of the trials. GERD was mentioned as an exclusion criterion in all trials. Rhinosinusitis or PNDS was assessed and excluded according to diagnosis or negative treatment trial in nine studies. One RCT allowed entry of patients with untreated nasal allergies.22

None of the studies reported the quantitative results of treatment trials conducted prior to randomization or how their outcomes were assessed. Treatment trials were specifically noted to have been conducted for the following reasons: nasal disease, seven trials; GERD, eight trials; and asthma, six trials.

Investigation for causes of chronic cough was reported for each study, but the intensity of the investigation varied. Chest radiography was reported in 10 studies, bronchial hyperresponsiveness (BHR) in six studies, sinus imaging in six studies, and investigation of GERD by using esophageal pH probe monitoring in two studies. More specialized investigation for causes of cough with a chest CT radiographic scan of the thorax (one study), induced sputum (for eosinophilic bronchitis, three studies), or polysomnography (for obstructive sleep apnea, no studies) were uncommon.

1. In adult patients with chronic cough, we suggest that unexplained chronic cough be diagnosed as a cough that persists longer than 8 weeks, and remains unexplained after investigation, and supervised therapeutic trial(s) conducted according to published best-practice guidelines (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

2. In adult patients with chronic cough, we suggest that patients with chronic cough undergo a guideline/protocol based assessment process that includes objective testing for bronchial hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilic bronchitis, or a therapeutic corticosteroid trial (Ungraded Consensus-Based Statement).

Treatment: RCTs

The treatments assessed in this review were grouped into several categories.

-

1.

Nonpharmacologic therapies: a multimodality speech pathology-therapy based intervention was identified.

-

2.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS): this strategy targets airway inflammation, predominantly eosinophilic inflammation that occurs in asthma, rhinitis, and nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis (Table 7).

-

3.

Neuromodulatory therapies: this group included therapies with known action on neural pathways, such as amitriptyline, gabapentin, and morphine (Table 8).37, 38

-

4.

Other therapies (Table 7): esomeprazole, erythromycin, ibuprofen, and ipratropium.

Table 7.

Overall Summary Treatment Effects from RCTs of UCC

| Citation | Intervention | Cough Severity | Cough Frequency | Cough QOL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonpharmacologic | ||||

| Vertigan et al23 | Speech therapy | + | NA | NA |

| Inhaled corticosteroid | ||||

| Rytila et al27 | Mometasone 400 μg once daily | ?+ | NA | NA |

| Ribeiro et al29 | Beclomethasone 500 μg tid | + | NA | NA |

| Pizzichini et al39 | Budesonide 400 mg bid | − | NA | NA |

| Neuromodulators | ||||

| Khalid et al24 | TRPV antagonist SB-705498 600 mg single dose | − | − | − |

| Ryan et al34 | Gabapentin 900 mg bid | + | + | + |

| Morice et al25 | Morphine 10 mg bid | + | NA | + |

| Jeyakumar et al22 | Amitriptyline 10 mg nocte | NA | NA | + |

| Other | ||||

| Shaheen et al36 | Esomeprazole 40 mg bd | − | NA | − |

| Yousaf et al35 | Erythromycin 250 mg qd | NA | ? | − |

| Sher et al19 | Memantine 20 mg daily | NR | NR | NR |

| Holmes et al26 | Inhaled ipratropium bromide 80 μg qid | + | NA | NA |

− = no effect; NR = not reported; + = positive effect; QOL = quality of life; ? = possible effect in direction shown; RCT = randomized controlled trial; UCC = unexplained chronic cough. See Table 2 legend for expansion of other abbreviations.

Table 8.

Effects of Neuromodulator Therapies on Cough in LCQ and CQLQ

| Study | Change in LCQ From Baseline |

Change in CQLQ From Baseline |

MID and Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jeyakumar et al,22 2006 | NA | Amitriptyline: 24.53; guaifenesin-codeine: 2.92 (Note: Wang Gang estimated the scores according to Fig 1 provided by the author) | MID based on 2 methods: GRCS (10.58 ± 10.63) and Punum Ladder (21.89 ± 15.38]).37 |

| Morice et al,25 2007 | LCQ: morphine, 3.2; placebo, 1.2 Subdomains in LCQ (95% CI): physical, –1.1 to –4.3; psychological, –1.1 to –3.9; social, –1.7 to –3.0 |

NA | MID in LCQ is 1.3 ± 3.2 and MID for subdomains in LCQ is 0.2 ± 0.8 in physical, 0.8 ± 1.5 in psychological, and 0.2 ± 1.1 in social.38 |

| Ryan et al,34 2012 | LCQ: gabapentin, 2.5; placebo, 1.1 |

CQLQ = cough-specific quality-of-life questionnaire; GRCS = Global Rating of Change Scale; LCQ = Leicester Cough Questionnaire; MID = minimum important difference. See Table 2 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Nonpharmacologic Therapies

A RCT reported a positive benefit on cough severity when a multimodality speech pathology therapy-based intervention was used.23 No adverse effects were reported. Chamberlain et al30 published a systematic review of nonpharmacologic therapy for refractory chronic cough. The authors identified English-language reports that investigated nonpharmacologic treatment of refractory chronic cough in adults published between 1980 and 2012. This review identified one RCT (by Vertigan et al23) and several observational studies. The intervention included two to four sessions of education, cough suppression techniques, breathing exercises, and counseling. The intervention resulted in a reduction in cough frequency (three studies), an improvement in cough severity (two studies), and a beneficial effect on cough-related quality of life (four studies). Although the review found support for nonpharmacologic therapy for UCC, it also noted the paucity of high-quality evidence and the need for additional studies.

3. In adult patients with unexplained chronic cough, we suggest a therapeutic trial of multimodality speech pathology therapy (Grade 2C).

Inhaled Corticosteroids

ICS were studied in three randomized trials. Different agents were used in each trial and at different comparative doses (mometasone, budesonide, and beclomethasone). ICS were found to improve cough severity in two studies,28, 29 but no other patient-reported outcomes were reported. No adverse effects were reported.

ICS target airway inflammation, predominantly eosinophilic inflammation that occurs in asthma, rhinitis, and nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis. A significant limitation of two of these RCTs28, 29 is that they did not include optimal assessment of asthma (with BHR testing) or eosinophilic bronchitis (with induced sputum testing or exhaled nitric oxide) as part of the cough evaluation when assessing eligibility for study entry. BHR testing was, however, included as part of the follow-up assessment, and BHR was identified in up to 50% of the participants in one study.28 This finding indicates an intervention fidelity bias in which 50% of included patients may have had asthma rather than UCC.

BHR and induced sputum testing were included in the study by Pizzichini et al.39 A positive BHR test result was an exclusion criterion. Each of the included participants had a negative result on induced sputum testing for eosinophils. Pizzichini et al39 found no beneficial effect of inhaled budesonide on cough symptoms in their population of nonasthmatic, noneosinophilic subjects with UCC.

Johnstone et al33 performed a systematic review to assess whether ICS could cure UCC in adults. Eight eligible RCTs were identified involving 570 participants. The studies were heterogeneous with respect to cough duration (> 3 weeks to > 8 weeks) and the lack of exclusion of other cough-related conditions. For example, four of the included studies permitted subjects with associated GERD and three permitted associated PNDS. The studies were of good quality but were heterogeneous, which precluded meta-analysis. Overall, ICS treatment led to a significant reduction in cough score, but analysis of the primary outcome (cure) was not possible because of study heterogeneity.

BHR testing is recommended as part of the diagnostic assessment of chronic cough when asthma is a consideration.2 It is likely that a more complete diagnostic evaluation is required to assess coexisting asthma.

4. In adult patients with unexplained chronic cough and negative tests for bronchial hyperresponsiveness and eosinophilia (sputum eosinophils, exhaled nitric oxide), we suggest that inhaled corticosteroids not be prescribed (Grade 2B).

Neuromodulatory Therapies

Neuromodulatory agents are believed to act on the enhanced neural sensitization that is a key component of unexplained cough. Each of the centrally acting neuromodulators (amitriptyline, gabapentin, and morphine) had positive effects on cough-specific quality of life. The magnitude of this effect exceeded the minimum important difference for the instruments used in two studies (Table 8). There was significant potential for selection bias (Fig 3B), and because we were unable to verify the reporting of the amitriptyline results, this agent was not included in the recommendations.

In the study by Ryan et al,34 adverse events were reported in 31% of the gabapentin group and included confusion, dizziness, dry mouth, fatigue, and/or nausea; blurred vision, headache, and memory loss was reported in only one patient each. Adverse events were reported in 10% of the placebo group, and there was no statistically significant difference in adverse events between the gabapentin and placebo groups. In the study by Morice et al,25 morphine was well tolerated, and no patients dropped out because of adverse events. The most common adverse effects noted were constipation (40%) and drowsiness (25%). The study by Jeyakumar et al22 did not report adverse effects.

Cohen and Misono32 performed a systematic review of neuromodulatory therapy for chronic idiopathic cough. Chronic cough was defined as > 6 weeks’ duration, which is shorter than the guideline definition of > 8 weeks. Idiopathic cough was identified by eliminating articles that included participants with cough due to other conditions, such as reflux disease, sinonasal pathology, allergy, pulmonary diseases, and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor treatment. Eight relevant articles were evaluated, including two RCTs.22, 34 A broad range of neuromodulators was studied, including gabapentin, pregabalin, amitriptyline, and baclofen. The review identified positive effects of neuromodulator therapy on cough-specific quality of life and cough severity, and it recommended further study design improvements for future research.

This class of therapy seems promising for the treatment of UCC. For each of the agents (morphine, amitriptyline, and gabapentin), there is a single positive RCT. Adverse effects can be significant and limit the maximum tolerable dose of these agents. Their role in therapy in relation to speech pathology interventions must be defined and improvements made to understand their adverse event profiles.

Based on the available evidence, an initial weak recommendation addressing gabapentin and morphine was proposed to the CHEST Expert Cough Panel. Only 75% of the panelists who voted were in favor of this recommendation, and it therefore failed to pass. Based on feedback from the voting panelists, the authors subsequently split the recommendation into two recommendations, one addressing gabapentin and the other addressing morphine. Wording was added to both recommendations suggesting that reassessment of the risk-benefit profile be performed at 6 months. Dosing information based on the RCT conducted by Ryan et al34 was also added to the gabapentin recommendation. The gabapentin recommendation passed with an approval of 90% of the votes; the morphine recommendation failed to pass, however, with an approval of only 71% of the votes. Based on further feedback from the voting panelists, the morphine recommendation was again revised and wording was added suggesting that morphine could be used when all other therapeutic options have failed to improve cough and there was close follow-up at 1 week and then monthly. During the third and final round of voting, the recommendation still failed to pass, with only 75% of the votes approving of the recommendation (to meet approval, an approval score of 80% was needed). The morphine recommendation was therefore removed from this guideline.

5. In adult patients with unexplained chronic cough, we suggest a therapeutic trial of gabapentin as long as the potential side effects and the risk-benefit profile are discussed with patients before use of the medication, and there is a reassessment of the risk-benefit profile at 6 months before continuing the drug (Grade 2C).

Remarks: Because health-related quality of life of some patients can be so adversely impacted by their unexplained chronic cough, and because gabapentin has been associated with improvement in quality of life in a randomized controlled clinical trial, the CHEST Cough Expert Panel believes that the potential benefits in some patients outweigh the potential side effects. With respect to dosing, patients who have no contraindications to gabapentin can be prescribed a dose escalation schedule beginning at 300 mg once a day; additional doses can be added each day as tolerated up to a maximum tolerable daily dose of 1,800 mg a day in two divided doses.

Other Therapies

Esomeprazole

Esomeprazole, a proton pump inhibitor, was studied in high doses for the treatment of UCC.36 No benefits on cough severity or quality of life were observed, suggesting that there was no evidence that the chronic cough was due to acid reflux with GERD. Moreover, there were no serious adverse events, and no one was withdrawn from the study for safety. The study power was calculated to detect a 1 SD change in the cough-specific quality-of-life questionnaire.

6. In adult patients with unexplained chronic cough and a negative workup for acid reflux disease, we suggest that proton pump inhibitor therapy not be prescribed (Grade 2C).

Erythromycin

Erythromycin was found to be ineffective in patients with UCC.35 The study had 80% power to detect a 50% reduction in cough frequency. The authors did not report any adverse events. Erythromycin should be well tolerated in this study: it was prescribed at a low dosage, and all subjects completed the study except for two withdrawals for personal reasons. Because erythromycin is an experimental therapy for UCC and is not widely used for UCC, this agent was not included in recommendations.

Ipratropium Bromide

A randomized trial of inhaled ipratropium bromide for unexplained cough reported a significant reduction in cough severity and a good safety profile.26 Subsequent research has identified an inhibitory effect of this class of medication on type 1 neuronal transient receptor potential vanilloid (TRPV1) receptors.40 However, this agent was not included in the recommendations because the ipratropium findings were from an older study, with a small sample size and limited reporting of methods, and the results have not been replicated.

Symptomatic Treatment: Systematic Review

Yancy et al31 reported a comparative effectiveness review of symptomatic treatments for chronic cough, based on 43 English-language articles published up to June 2012 and involving 3,067 participants. Study quality was mixed and rated as good (11 studies), fair (30 studies), or poor (eight studies). The review highlighted the problems of successfully treating UCC and stated that the purpose of the review was to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments for the symptom of chronic cough in patients with UCC or refractory chronic cough. Articles were excluded if the therapy was directed at an underlying cause.

Although participants in the studies were required to have UCC, most (36 of 49 [74%]) of the included articles studied patients with chronic cough associated with a disease known to cause cough (eg, COPD, chronic bronchitis, tuberculosis, lung cancer, asthma). Five articles addressed UCC as defined by our review, and four articles included patients with UCC as well as cough in association with a defined cough-related disease. In the selection of studies for inclusion, 73 articles were excluded because the study population did not have chronic cough of unknown cause or refractory cough of known cause. The reproducibility and validity of the judgements about including or excluding articles based on the assessment of UCC in the setting of participants with a known cough-related disease were incompletely described, and this factor was acknowledged as a limitation of the systematic review. In their methods, the authors state, “Because determination of whether an individual’s chronic cough was truly unexplained or refractory was often difficult or impossible given available descriptions in the published article, we did not exclude articles based on diagnostic evaluation or empiric therapeutic trials, but rather described such information in an attempt to infer to what extent study populations could be considered unexplained or refractory according to current criteria.” This statement indicates that requirements for a diagnostic and therapeutic evaluation were not inclusion criteria in the definition of UCC. Consequently, in their discussion, the authors noted that only a minority of articles included participants who had a high probability of having UCC and that this factor would limit the applicability of their findings. They stated, “Few studies directly reported assembling patients fitting our intended population of idiopathic or refractory chronic cough. Only three studies, including one of assessing the effect of morphine, were clearly in patients with unexplained cough and required subjects to have gone through a diagnostic evaluation to exclude most causes of cough.”

Importantly, the concept of UCC as evaluated in the review by Yancy et al31 differs from that which has been addressed in the present review. The two reviews differ significantly in the area of study selection, particularly as it relates to participant characterization. Our review sought carefully to define the population in the evidence base and, in doing so, increases the applicability of the results to a clinically recognizable population seen in secondary or tertiary care settings.

Discussion

Diagnosis

Chronic cough is difficult to treat when it is unexplained or fails to respond to therapy. Based on this systematic review, the present guideline makes several suggestions for the assessment and treatment of UCC. The terms “unexplained chronic cough,” “difficult-to-treat cough,” or “refractory chronic cough” were considered appropriate descriptors by the guideline panel. The condition is defined as a chronic cough that persists after comprehensive investigation, medical assessment, and optimal trials of indicated therapy in an adherent patient.

The key elements of this definition are the requirements for adequate assessment, investigation, and therapy. These processes are detailed in the CHEST chronic cough guideline,2 as well as in other cough reviews.4, 5 The completeness of this assessment and treatment approach according to the five areas of intervention fidelity (study design, training of providers, delivery of treatment, receipt, and enactment of treatment)41 is recognized as an important paradigm in the determination of UCC. Although the studies reviewed in this assessment showed fair to good adherence to intervention fidelity, there are clearly opportunities to provide better documentation of the assessment process in published reports. There is also a need to consistently use validated outcome assessment tools when evaluating treatment response in chronic cough. Current CHEST guidelines directed at strengthening future studies of cough provide recommendations for incorporating the use of an intervention manual and other intervention fidelity strategies in chronic cough studies41 and also detail validated tools developed for assessing cough outcomes.42 The use of an intervention fidelity tool will facilitate the strengthening of study quality in chronic cough research.41 Intervention fidelity bias was identified as a problem in studies of ICS for unexplained chronic cough; these studies included incomplete assessments of asthma, allergy, and nonasthmatic eosinophilic bronchitis. Specifically, this means that if a protocol-based clinical trial of ICS yielded no improvement (suggesting there was no airway inflammatory process as the basis for the cough and thus substantiating that the cough was an UCC), the recommendation is not to treat with ICS. The recommendation is that these conditions be objectively assessed before making a diagnosis of UCC. When this method was followed, ICS were shown to be ineffective in the treatment of UCC.39

Therapy

A wide range of therapies have been assessed in UCC.31 Neuromodulator therapy was found to significantly improve cough quality of life in three RCTs. Each study used a different intervention (gabapentin or morphine). The largest study (by Ryan et al34) also assessed cough frequency and found that gabapentin reduced cough frequency in UCC. The consistency of these positive results indicates that centrally acting mechanisms are important in UCC and should be studied further.

A treatment suggestion regarding neuromodulators for UCC recognized the limitations of the evidence, namely the paucity of studies, their comparatively small sample size, and the fact that one of the three RCTs had a moderate risk of bias; collectively, these factors mean that the estimate of treatment effect is imprecise. In addition, the treatments used did have adverse effects, mainly predictable central nervous system effects. In the case of gabapentin, these were reportedly managed by modification to dose.

Several other therapies were evaluated for UCC. Speech pathology was found to have a positive effect on cough severity, and a subsequent open-label study confirmed this finding and extended the results to show positive effects on cough quality of life and objective cough counts. Proton pump inhibitors are recommended for chronic cough caused by GERD. Because GERD can occur without typical esophageal symptoms, some authors have proposed that proton pump inhibitors be used for UCC. This theory was examined in an RCT, which found that in the absence of typical symptoms attributable to GERD, the empiric use of a high-dose proton pump inhibitor was not effective at improving cough quality of life.36 Similarly, macrolides did not improve quality of life in patients with UCC.35

Summary of the Systematic Review Results and Its Limitations

The present systematic review evaluated 11 RCTs and five systematic reviews that examined therapeutic interventions in UCC. There was substantial diversity in the terms used to describe UCC, and an agreed definition was not uniformly applied. Similarly, the assessment process was incompletely described in many studies. These aspects indicate that there may be heterogeneity in the patient population under study, and this limitation restricts the generalizability of the results. Intervention fidelity is now recognized as a key aspect in the diagnosis of UCC. This factor was incompletely reported in the studies included in the review, which indicates the possibility for indication bias in the studies evaluated. There was a range of interventions used, and none of these were replicated in other RCTs. The study sample sizes were relatively small, and a variety of outcome assessment tools were used, not all of which were adequately validated. These aspects of study design limit the strength of the conclusions.

Future Directions

The CHEST Expert Cough Panel considered ways to improve research in UCC by examining clinical trial design, chronic cough registries, and potential research questions (Table 9).

Table 9.

Future Research Directions in UCC

| Diagnosis | Study Design |

|---|---|

| What are the diagnostic criteria for UCC? | What does an ideal study look like [PICOD]? |

| Is there evidence of a specific phenotype of UCC? [eg, based on sex, BMI, post viral history] | P: population: how should the population be selected and assessed prior to entry |

| What is the place of cough sensitivity testing in UCC? | I: description of the intervention |

| Is UCC a diagnosis of exclusion? | C: placebo effect in cough studies |

| What is the place of cough sensitivity tests such as capsaicin in UCC? | O: outcomes measures: objective, subjective; response characteristics, |

| What is the prevalence of UCC when intervention fidelity to cough diagnosis is adequately assessed? | D: design: discuss relative merits of different designs, eg randomized vs. before-after; parallel vs cross-over; single vs. multiple interventions |

| What is the place of assessment and treatment for nonacid gastroesophageal reflux in the assessment of UCC? | |

| What is the comparative efficacy of diagnostic testing vs. empiric corticosteroid trials for assessment of eosinophilia airway diseases associated with chronic cough? |

PICO = population, intervention, comparison, outcome. See Table 7 legend for expansion of other abbreviation.

Study Population

The ideal clinical trial patient population in this area was considered to have UCC or refractory chronic cough, assessed according to guidelines, in which participants were not taking an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor and were nonsmokers. The diagnostic criteria for UCC must be carefully determined. This determination requires use of and adherence to an assessment manual which incorporates the five areas of intervention fidelity to determine that a subject truly has UCC. Drugs for coexisting conditions, such as proton pump inhibitors for GERD, are considered permissible as long as they are used at a stable dose. Participants require exclusion of significant chronic respiratory disease, such as chronic asthma, COPD, or bronchiectasis. These measures ensure a homogeneous study population. Participants should have sufficient and measurable cough severity at study entry.

Comparison Group

There can be a significant placebo effect in cough trials.

Outcome Measures

The CHEST Cough Expert Panel has recommended quality of life as the primary study outcome. In adults, use of the cough-specific quality-of-life questionnaire or the Leicester Cough Questionnaire is recommended.

Trial Design

For the study of chronic cough, either a parallel-group or crossover design is possible. For the study of acute or subacute cough, a parallel-group design is preferable because of a significant natural recovery in these conditions. Stratification for randomization based on sex and severity should be considered to avoid problems with statistical analysis because of the importance of these two variables on outcomes.

Chronic Cough Registries

Registries for UCC could be used to document patient characteristics and outcomes, as well as clinical trials in progress. They could also serve as a source of research participants for trials and may allow for phenotyping according to age, sex, cough duration, cough severity, cough reflex sensitivity (C2 and C5), and other biomarkers. Registries can be used for genetic studies in chronic cough.

The panel members were aware of several completed clinical trials with the following agents: memantine (results were presented as an abstract, and authors were requested to provide update; no reply was received as of August 2014); theobromine, P2X3 antagonists,43 pregabalin,44 and physiotherapy and speech and language therapy intervention (in submission).

Novel Therapeutic Agents

There are now numerous targets for novel therapeutic agents in UCC. These include peripheral targets, as well as the brainstem and cerebral cortex. The optimal site to target with intervention is not known.

TRPV1 Antagonists

A RCT of a TRPV1 antagonist observed a significant reduction in capsaicin cough reflex sensitivity.24 No changes in cough severity or quality of life were observed.

Conclusions

UCC requires further study to determine consistent terminology and the optimal methods of investigation using established criteria for intervention fidelity. Neuromodulatory therapies and speech pathology-based cough suppression are suggested as therapeutic options for UCC.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: P. G., G. W., L. M., A. E. V., K. W. A., and S. S. B. planned, reviewed, and edited the systematic review and guideline. The systematic review was conducted by G. W. and P. G.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: The authors have reported to CHEST the following: L. M. previously served on advisory boards for Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline in relation to novel compounds with a potential role in treatment of cough; he also served as chairman for the Mortality Adjudication Committee for UPLIFT and TIOSPIR, two Phase IV COPD clinical trials for Boehringer Ingelheim. None declared (P. G., G. W., A. E. V., K. W. A., S. S. B.).

Endorsements: This guideline has been endorsed by the American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery Foundation, the American Association for Respiratory Care, the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, the American Laryngological Association, the American Thoracic Society, the Canadian Thoracic Society, the Irish Thoracic Society, and the Lung Foundation Australia.

Collaborators: Todd M. Adams, MD (Webhannet Internal Medicine Associates of York Hospital, Moody, ME), Kenneth W. Altman, MD, PhD (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX), Alan F. Barker, MD (Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR), Surinder S. Birring, MB ChB, MD (Division of Asthma, Allergy and Lung Biology, King’s College London, Denmark Hill, London, United Kingdom), Fiona Blackhall, MD, PhD (University of Manchester, Department of Medical Oncology, Manchester, England), Donald C. Bolser, PhD (College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL), Louis-Philippe Boulet, MD, FCCP (Institut universitaire de cardiologie et de pneumologie de Québec [IUCPQ], Quebec, QC, Canada), Sidney S. Braman, MD, FCCP (Mount Sinai Hospital, New York, NY), Christopher Brightling, MBBS, PhD, FCCP (University of Leicester, Glenfield Hospital, Leicester, United Kingdom), Priscilla Callahan-Lyon, MD (US Food and Drug Administration, Rockville, MD), Brendan J. Canning, PhD (Johns Hopkins Asthma and Allergy Center, Baltimore, MD), Anne B. Chang, MBBS, PhD, MPH (Royal Children’s Hospital, Queensland, Australia), Remy Coeytaux, MD, PhD (Community and Family Health, Duke University, Durham, NC), Terrie Cowley (The TMJ Association, Milwaukee, WI), Paul Davenport, PhD (Department of Physiological Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL), Rebecca L. Diekemper, MPH (American College of Chest Physicians, Glenview, IL), Satoru Ebihara, MD, PhD (Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Toho University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan), Ali A. El Solh, MD, MPH (University at Buffalo, State University of New York, Buffalo, NY), Patricio Escalante, MD, MSc, FCCP (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Anthony Feinstein, MPhil, PhD (Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto, ON, Canada), Stephen K. Field, MD (University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada), Dina Fisher, MD, MSc (University of Calgary, Respiratory Medicine, Calgary, AB, Canada), Cynthia T. French, PhD, FCCP (UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, MA), Peter Gibson, MBBS (Hunter Medical Research Institute, New South Wales, Australia), Philip Gold, MD, MACP, FCCP (Loma Linda University, Loma Linda, CA), Michael K. Gould, MD, MS, FCCP (Kaiser Permanente, Pasadena, CA), Cameron Grant, MB ChB, PhD (University of Auckland School of Medicine, Auckland, New Zealand), Susan M. Harding, MD, FCCP (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL), Anthony Harnden, MB ChB, MSc (University of Oxford, Oxford, England), Adam T. Hill, MB ChB, MD (Royal Infirmary and University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, Scotland), Richard S. Irwin, MD, Master FCCP (UMass Memorial Medical Center, Worcester, MA), Peter J. Kahrilas, MD (Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL), Karina A. Keogh, MD (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Andrew P. Lane, MD (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD), Kaiser Lim, MD (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Mark A. Malesker, PharmD, FCCP (Creighton University School of Pharmacy and Health Professions, Omaha, NE), Peter Mazzone, MD, MPH, FCCP (The Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH), Stuart Mazzone, PhD, FCCP (University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia), Douglas C. McCrory, MD, MHS (Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, NC), Lorcan McGarvey, MD (The Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, United Kingdom), Alex Molasiotis, PhD, MSc, RN (Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong Kong, China), M. Hassan Murad, MD, MPH (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Peter Newcombe, PhD (School of Psychology University of Queensland, Queensland, Australia), Huong Q. Nguyen, PhD, RN (Kaiser Permanente, Pasadena, CA), John Oppenheimer, MD (UMDNJ-Rutgers University, Newark, NJ), David Prezant, MD (New York City Fire Department, Brooklyn, NY), Tamara Pringsheim, MD (Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, AB, Canada), Marcos I. Restrepo, MD, MSc, FCCP (South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX), Mark Rosen, MD, Master FCCP (American College of Chest Physicians, Glenview, IL), Bruce Rubin, MEngr, MD, MBA (Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA), Jay H. Ryu, MD, FCCP (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN), Jaclyn Smith, MB ChB, PhD (University of Manchester, Manchester, England), Susan M. Tarlo, MBBS, FCCP (Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada), Anne E. Vertigan, PhD, MBA, BAppSc (SpPath) (John Hunter Hospital, New South Wales, Australia), Gang Wang, MD, PhD (Sichuan University, West China Hospital, Chengdu, China), Miles Weinberger, MD, FCCP (University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics, Iowa City, IA), Kelly Weir, MsPath (Queensland Children’s Medical Research Institute, Queensland, Australia), and Renda Soylemez Wiener, MD, MPH (The Pulmonary Center, Boston University School of Medicine, Edith Nourse Rogers Memorial VA Hospital, Bedford, MA).

Role of sponsors: CHEST was the sole supporter of these guidelines, this article, and the innovations addressed within.

Other contributions: Richard S. Irwin, MD, Master FCCP, and Cynthia T. French, PhD, ANP-BC, FCCP, provided input to the design, planning interpretation and editing of the systematic review and guideline. Ms Diekemper, MPH, provided input to the interpretation and editing of the systematic review and guideline.

Additional information: The e-Table can be found in the Supplemental Material section of the online article.

Footnotes

DISCLAIMER: American College of Chest Physician guidelines are intended for general information only, are not medical advice, and do not replace professional medical care and physician advice, which always should be sought for any medical condition. The complete disclaimer for this guideline can be accessed at http://www.chestnet.org/Guidelines-and-Resources/Guidelines-and-Consensus-Statements/CHEST-Guidelines.

Contributor Information

Peter Gibson, Email: peter.gibson@hnehealth.nsw.gov.au.

CHEST Expert Cough Panel:

Todd M. Adams, Kenneth W. Altman, Alan F. Barker, Surinder S. Birring, Fiona Blackhall, Donald C. Bolser, Louis-Philippe Boulet, Sidney S. Braman, Christopher Brightling, Priscilla Callahan-Lyon, Brendan J. Canning, Anne B. Chang, Remy Coeytaux, Terrie Cowley, Paul Davenport, Rebecca L. Diekemper, Satoru Ebihara, Ali A. El Solh, Patricio Escalante, Anthony Feinstein, Stephen K. Field, Dina Fisher, Cynthia T. French, Peter Gibson, Philip Gold, Michael K. Gould, Cameron Grant, Susan M. Harding, Anthony Harnden, Adam T. Hill, Richard S. Irwin, Peter J. Kahrilas, Karina A. Keogh, Andrew P. Lane, Kaiser Lim, Mark A. Malesker, Peter Mazzone, Stuart Mazzone, Douglas C. McCrory, Lorcan McGarvey, Alex Molasiotis, M. Hassan Murad, Peter Newcombe, Huong Q. Nguyen, John Oppenheimer, David Prezant, Tamara Pringsheim, Marcos I. Restrepo, Mark Rosen, Bruce Rubin, Jay H. Ryu, Jaclyn Smith, Susan M. Tarlo, Anne E. Vertigan, Gang Wang, Miles Weinberger, Kelly Weir, and Renda Soylemez Wiener

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Head J.R. Persistent cough of unexplained origin. Med Clin North Am. 1958;42(1):147–154. doi: 10.1016/s0025-7125(16)34331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Irwin R.S., Baumann M.H., Bolser D.C. Diagnosis and management of cough executive summary: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1 suppl):1S–23S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.1S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pratter M.R. Unexplained (idiopathic) cough: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(supp 1):220S–221S. doi: 10.1378/chest.129.1_suppl.220S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pavord I.D., Chung K.F. Management of chronic cough. Lancet. 2008;371(9621):1375–1384. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60596-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGarvey L. The difficult-to-treat, therapy-resistant cough: why are current cough treatments not working and what can we do? Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2013;26(5):528–531. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irwin R.S., Ownbey R., Cagle P.T. Interpreting the histopathology of chronic cough: a prospective, controlled, comparative study. Chest. 2006;130(2):362–370. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.2.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis S.Z., Diekemper R., Ornelas J., Casey K.R. Methodologies for the development of CHEST guidelines and expert panel reports. Chest. 2014;146(1):182–192. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang X., Lin J., Demner-Fushman D. Evaluation of PICO as a knowledge representation for clinical questions. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2006:359–363. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins J.P., Altman D.G., Gotzsche P.C. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diekemper R., Ireland B., Merz L. Development of the documentation and appraisal review tool (DART) for systematic reviews. Br Med J Qual Safety. 2013:61–62. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song M., Happ M., Sandelowski M. Development of a tool to assess fidelity to a psycho-educational intervention. J Adv Nurs. 2010;66(3):673–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.05216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Han B., Jang S.H., Kim Y.J. The efficacy of inhaled corticosteroid on chronic idiopathic cough. Tuberc Respir Dis. 2009;67:422–429. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang J., Luo Q., Shentu Y. Prevention of refractory cough with mediastinal fat to fill the residual cavity after radical systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy in patients with right lung cancer [in Chinese] Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2010;13(10):975–979. doi: 10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2010.10.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J., Luo Q., Tan Q. Evaluation of the surgical fat-filling procedure in the treatment of refractory cough after systematic mediastinal lymphadenectomy in patients with right lung cancer. J Surg Res. 2014;187(2):490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2013.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gastpar H., Criscuolo D., Dieterich H.A. Efficacy and tolerability of glaucine as an antitussive agent. Curr Med Res Opin. 1984;9(1):21–27. doi: 10.1185/03007998409109554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chaudhuri R., McMahon A.D., Thomson L.J. Effect of inhaled corticosteroids on symptom severity and sputum mediator levels in chronic persistent cough. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chmelik M., J S Therapie des chronishen therapierefraktaren hastens mit Gabapentin. Pneumologe. 2013;10:341–342. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vertigan A.E., Theodoros D.G., Winkworth A.L. A comparison of two approaches to the treatment of chronic cough: perceptual, acoustic, and electroglottographic outcomes. J Voice. 2008;22(5):581–589. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2007.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sher M., Goldsobel A., Birring S. An exploratory, randomized, placebo-controlled double-blind, crossover study of FP01 lozenges in subjects with chronic refractory cough. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2013;111(5 suppl 1):A108. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dales R.E., Lunau M.A., Tierney M.G. Chronic cough responsive to ibuprofen. Pharmacotherapy. 1992;12(4):331–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chamberlain S., Garrod R., Birring S.S. Cough suppression therapy: does it work? Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2013;26(5):524–527. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2013.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeyakumar A., Brickman T.M., Haben M. Effectiveness of amitriptyline versus cough suppressants in the treatment of chronic cough resulting from postviral vagal neuropathy. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(12):2108–2112. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000244377.60334.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vertigan A.E., Theodoros D.G., Gibson P.G. Efficacy of speech pathology management for chronic cough: a randomised placebo controlled trial of treatment efficacy. Thorax. 2006;61(12):1065–1069. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.064337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khalid S., Murdoch R., Newlands A. Transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) antagonism in patients with refractory chronic cough: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(1):56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morice A.H., Menon M.S., Mulrennan S.A. Opiate therapy in chronic cough. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(4):312–315. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200607-892OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holmes P.W., Barter C.E., Pierce R.J. Chronic persistent cough: use of ipratropium bromide in undiagnosed cases following upper respiratory tract infection. Respir Med. 1992;86(5):425–429. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(06)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rytila P., Ghaly L., Varghese S. Treatment with inhaled steroids in patients with symptoms suggestive of asthma but with normal lung function. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(4):989–996. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00062307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kastelik J.A., Aziz I., Ojoo J.C., Thompson R.H., Redington A.E., Morice A.H. Investigation and management of chronic cough using a probability-based algorithm. Eur Respir J. 2005;25(2):235–243. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00140803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ribeiro M., Pereira C.A., Nery L.E. High-dose inhaled beclomethasone treatment in patients with chronic cough: a randomized placebo-controlled study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60623-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chamberlain S., Birring S.S., Garrod R. Nonpharmacological interventions for refractory chronic cough patients: systematic review. Lung. 2014;192(1):75–85. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9508-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yancy W.S., Jr., McCrory D.C., Coeytaux R.R. Efficacy and tolerability of treatments for chronic cough: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2013;144(6):1827–1838. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen S.M., Misono S. Use of specific neuromodulators in the treatment of chronic, idiopathic cough: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;148(3):374–382. doi: 10.1177/0194599812471817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnstone K.J., Chang A.B., Fong K.M. Inhaled corticosteroids for subacute and chronic cough in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;3:CD009305. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009305.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryan N.M., Birring S.S., Gibson P.G. Gabapentin for refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380(9853):1583–1589. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60776-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yousaf N., Monteiro W., Parker D. Long-term low-dose erythromycin in patients with unexplained chronic cough: a double-blind placebo controlled trial. Thorax. 2010;65(12):1107–1110. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.142711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaheen N.J., Crockett S.D., Bright S.D. Randomised clinical trial: high-dose acid suppression for chronic cough—a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(2):225–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2010.04511.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fletcher K.E., French C.T., Irwin R.S., Corapi K.M., Norman G.R. A prospective global measure, the Punum Ladder, provides more valid assessments of quality of life than a retrospective transition measure. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(10):1123–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raj A.A., Pavord D.I., Birring S.S. Clinical cough IV: what is the minimal important difference for the Leicester Cough Questionnaire? Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2009;(187):311–320. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-79842-2_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pizzichini M.M., Pizzichini E., Parameswaran K. Nonasthmatic chronic cough: no effect of treatment with an inhaled corticosteroid in patients without sputum eosinophilia. Can Respir J. 1999;6(4):323–330. doi: 10.1155/1999/434901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Birrell M.A., Bonvini S.J., Dubuis E. Tiotropium modulates transient receptor potential V1 (TRPV1) in airway sensory nerves: a beneficial off-target effect? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(3):679–687. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.French C.T., Diekemper R.L., Irwin R.S., CHEST Expert Cough Panel Assessment of intervention fidelity and recommendations for researchers conducting studies on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic cough in the adult: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2015;148(1):32–54. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boulet L.P., Coeytaux R.R., McCrory D.C., CHEST Expert Cough Panel Tools for assessing outcomes in studies of chronic cough: CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2015;147(3):804–814. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Abdulqawi R., Dockry R., Holt K. P2X3 receptor antagonist [AF-219] in refractory chronic cough: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2015;385(9974):1198–1205. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61255-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vertigan AE, Kapela SL, Ryan NM, Birring SS, McElduff P, Gibson PG. Pregabalin and speech pathology combination therapy for refractory chronic cough: A randomised controlled trial [published online ahead of print October 8, 2015]. Chest. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1271 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.