Abstract

TGFβ is a potent regulator of several biological functions in many cell types, but its role in the differentiation of human bone marrow-derived skeletal stem cells (hMSCs) is currently poorly understood. In the present study, we demonstrate that a single dose of TGFβ1 prior to induction of osteogenic or adipogenic differentiation results in increased mineralized matrix or increased numbers of lipid-filled mature adipocytes, respectively. To identify the mechanisms underlying this TGFβ-mediated enhancement of lineage commitment, we compared the gene expression profiles of TGFβ1-treated hMSC cultures using DNA microarrays. In total, 1932 genes were upregulated, and 1298 genes were downregulated. Bioinformatics analysis revealed that TGFβl treatment was associated with an enrichment of genes in the skeletal and extracellular matrix categories and the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. To investigate further, we examined the actin cytoskeleton following treatment with TGFβ1 and/or cytochalasin D. Interestingly, cytochalasin D treatment of hMSCs enhanced adipogenic differentiation but inhibited osteogenic differentiation. Global gene expression profiling revealed a significant enrichment of pathways related to osteogenesis and adipogenesis and of genes regulated by both TGFβ1 and cytochalasin D. Our study demonstrates that TGFβ1 enhances hMSC commitment to either the osteogenic or adipogenic lineages by reorganizing the actin cytoskeleton.

1. Introduction

Fat and bone tissues both originate from bone marrow progenitor cells called skeletal stem cells, also known as bone marrow-derived multipotent stromal cells or mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs). The formation of these tissues is regulated throughout an organism's lifetime by homeostatic mechanisms within the marrow cavity. It has been suggested that an imbalance between osteogenic and adipogenic lineage commitment and differentiation is responsible for age-related impairment of bone formation, and a number of therapeutic interventions targeting and activating MSCs, thus enhancing bone mass, have been proposed. Indeed, the identification of novel strategies to steer human skeletal (mesenchymal) stem cell differentiation towards the production of osteoblastic cells, thus increasing bone formation, is very topical in the bone biology field.

The transforming growth factor (TGF) superfamily consists of over 40 members, including activins, inhibins, bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), growth and differentiation factors (GDFs), and TGFβs [1]. TGF family members are multifunctional regulators of cell growth and differentiation, playing pivotal roles during embryonic development, organogenesis, and tissue homeostasis [2]. The cytokine TGFβ1 is among the most abundant in bone matrix [3] and is secreted by endothelial cells, epithelial cells, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, and most immune cells [4]. TGFβ1 is deposited in bone matrix as an inactive, latent complex with latency-associated protein (LAP), the binding of which masks the receptor domains of active TGFβ1. During bone formation, osteoclast-mediated bone resorption activates TGFβ1 by cleaving LAP and releasing it from bone matrix, thus creating a transient gradient of active TGFβ1 that attracts MSCs to bone remodeling sites, where they undergo osteoblastic differentiation [5]. Furthermore, TGFβ1 is known to regulate the proliferation and differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells [6].

Actin microfilaments are composed of polymers of actin, the most abundant cellular protein which also forms the thinnest part of the cytoskeleton, and are primarily responsible for skeletal structure [7]. Cellular actin exists in two forms, filamentous polymerized actin (F-actin) and globular/monomer depolymerized actin (G-actin), and transitions between these forms during highly dynamic intracellular polymerization and depolymerization processes [8]. In mammals, actin polymerization factors regulate actin polymerization and depolymerization [9]. While the stiffness of actin is lower than that of microtubules, actin molecules form a highly organized structural network, supported by a large number of interacting cross-linking proteins, which together confer a substantial amount of mechanical strength [10]. The cytoskeleton is known to be important for determining cell morphology and for mediating changes in adhesion and differentiation [11]. Indeed, during human MSC (hMSC) lineage commitment, cells undergo significant morphological changes and actin cytoskeletal reorganization which contribute to the determination of cellular fate [7, 12].

In this study, we investigated the effect of TGFβ-induced actin cytoskeleton modifications on the potential of hMSCs to differentiate into osteogenic and adipogenic lineages, as well as the effect of the actin polymerization inhibitor cytochalasin D (CYD). Our data suggest that TGFβ-induced actin cytoskeleton reorganization is a prerequisite for hMSC differentiation into osteocytic or adipocytic lineages.

2. Results

2.1. TGFβ1 Treatment Enhanced the Osteogenic Differentiation of hMSCs

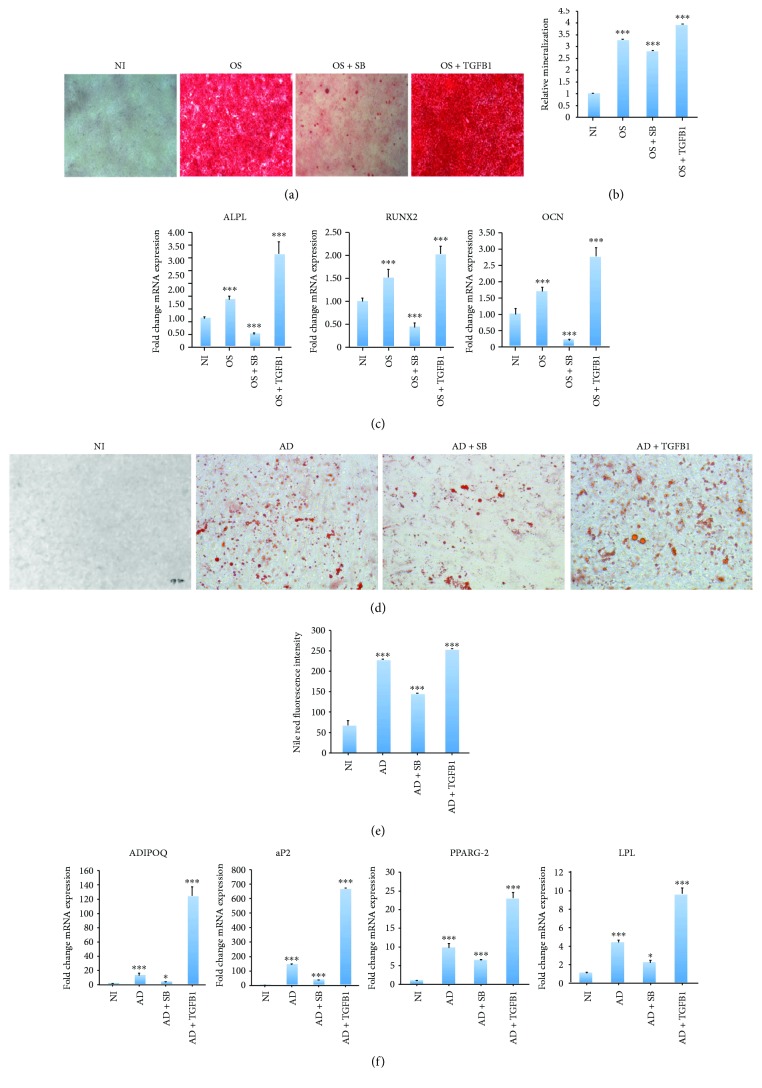

A single treatment with TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml, for 2 days) enhanced hMSC osteogenic differentiation, as shown by the increased mineralized matrix formation made evident by alizarin red S staining (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). Conversely, when TGFβ1 signaling was blocked with the inhibitor SB-431542 (10 μM), significantly lower mineralized matrix formation was observed (Figures 1(a) and 1(b)). Consistent with this, higher expression of the osteoblastic genes alkaline phosphatase (ALP), runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2), and osteocalcin (OCN) was observed in hMSCs undergoing osteogenic differentiation in the presence of TGFβ1, while treatment with the TGFβ1 inhibitor SB-431542 severely inhibited this expression (Figure 1(c)).

Figure 1.

TGFβ1 induces osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation. MSCs underwent osteogenic or adipogenic differentiation by culturing cells in the appropriate medium for 7 days. (a) Micrographs showing the degree of mineralized calcium deposition in noninduced cells (NI), osteoinduced cells (OS), osteoinduced cells + SB-431542 (OS + SB), and osteoinduced cells + TGFβ1 (OS + TGFB), as assessed by alizarin red S staining (20x magnification). (b) Quantification of mineralization in the alizarin red S stained groups shown in (a). Data are shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (∗∗∗ p < 0.005). (c) mRNA expression of the osteogenic markers ALPL, RUNX2, and OCN, normalized to GAPDH, as determined by RT-PCR. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (∗ p < 0.05; ∗∗∗ p < 0.0005). (d) Micrographs showing the accumulation of lipid droplets in noninduced cells (NI), adipoinduced cells (AD), adipoinduced cells + SB-431542 (AD + SB), and adipoinduced cells + TGFβ1 (AD + TGFB), as determined by Oil red O staining (20x magnification). (e) Quantification of mature adipocytes in the NI, AD, AD + SB, and AD + TGFB groups, as determined by Nile red fluorescence intensity. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (∗∗∗ p < 0.005). (f) mRNA expression of the adipogenic markers LPL, aP2, PPARG-2, and ADIPOQ, normalized to GAPDH, as determined by RT-PCR. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (∗ p < 0.05; ∗∗∗ p < 0.0005).

2.2. TGFβ1 Treatment Enhanced the Adipogenic Differentiation of hMSCs

Next, we examined the effect of treating hMSCs with a single dose of TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml, for 2 days) on adipogenic differentiation. We found that adipogenic differentiation was enhanced following TGFβ1 treatment, as shown by an increase in the number of lipid-filled adipocytes (Figures 1(d) and 1(e)). Similarly, the expression of several adipogenic gene markers, including lipoprotein lipase (LPL), peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma 2 (PPARG-2), adipocyte protein 2 (aP2), and ADIPOQ, was upregulated following TGFβ1 treatment, while treatment with SB-431542 reversed these effects (Figure 1(f)).

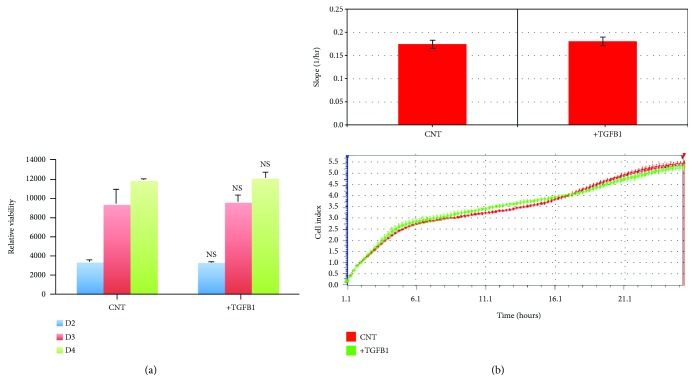

2.3. TGFβ1 Stimulation Has No Effect on hMSC Viability or Proliferation

The effect of TGFβ1 on hMSC cell viability was assessed using alamarBlue assay reagent. No significant effect on viability was observed after 4 days of treatment (Figure 2(a)). To investigate the effect of TGFβ1 on cellular proliferation, we used the xCELLigence RTCA DP® cell proliferation assay system, which allows the continuous monitoring of cell numbers over time. As shown in Figure 2(b), there was no measurable difference in hMSC proliferation in the presence or absence of TGFβ1.

Figure 2.

TGFβ1 does not affect hMSC proliferation or viability. (a) Chart showing the relative hMSC viability in the absence (CNT) or presence (TGFB1) of TGFβ1, as determined by alamarBlue assay reagent. Shown are cell viabilities on days 2 (D2), 3 (D3), and 4 (D4) of culture. (b) Real-time proliferation assay data using the xCELLigence RTCA DP system for hMSC cells with and without TGFβ1 treatment. Lower panel: cell proliferation was measured at 15-minute intervals for a total duration of 24 hours. Upper panel: summary data showing cellular proliferation after 24 hours. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of two independent experiments (n = 6). NS: not significant.

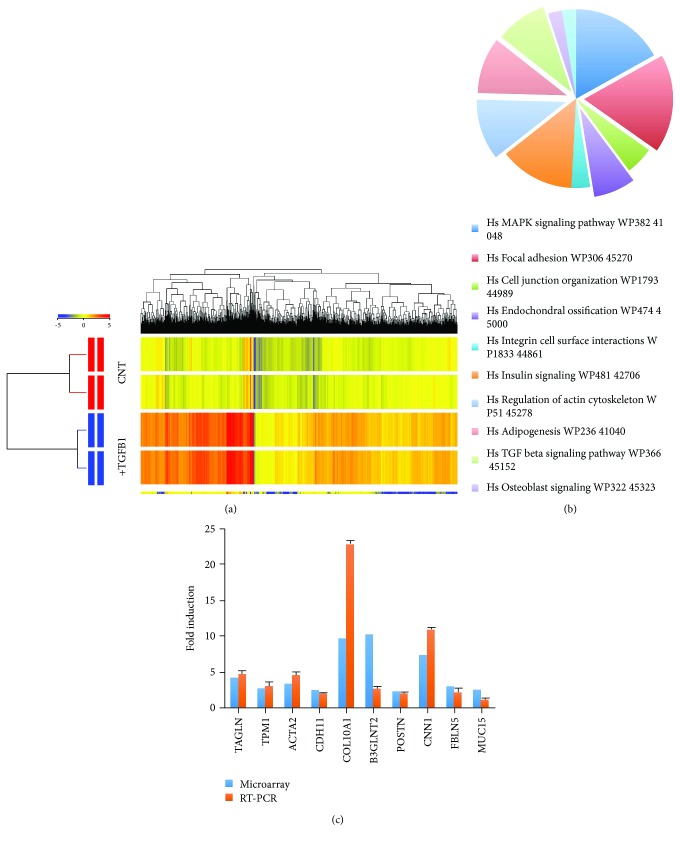

2.4. Molecular Phenotype of TGFβ1-Treated hMSCs

To understand the molecular mechanisms underlying the TGFβl-mediated regulation of hMSC differentiation, we compared global gene expression in TGFβl-treated hMSCs and vehicle-treated control cells using microarray analysis. In total, 1932 gene transcripts were significantly upregulated, and 1298 were significantly downregulated following TGFβl treatment. Significant changes were defined as a fold change ≥ 2, p < 0.05 and are listed in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes revealed a clear distinction between TGFβl-treated and control samples (Figure 3(a)). Next, we used performed gene ontology analysis to identify the biological processes that were favored following TGFβl treatment. We found that the genes that were significantly altered in TGFβl-treated MSCs were enriched within several skeletal and extracellular matrix categories, including extracellular matrix (53 genes), extracellular matrix organization (51 genes), and proteinaceous extracellular matrix (Supplementary Table S3). Furthermore, pathway analysis of significantly changed genes revealed the significant enrichment of several signaling pathways in TGFβl-treated hMSCs. Among these, the most enriched pathways were “regulation of actin cytoskeleton,” “MAPK signaling,” “focal adhesion,” “TGFβ1 signaling,” “adipogenesis,” “endochondral ossification,” and “osteoblast signaling” (Figure 3(b)). Table 1 lists the genes within osteogenesis- and adipogenesis-related signaling pathways that were upregulated in TGFβ1-treated cells. A selected panel of genes known to be involved in cell differentiation and TGFβ signaling that were significantly changed in the microarray data were examined by qRT-PCR. In general, a good degree of concordance was observed between the microarray and qRT-PCR data (Figure 3(c)).

Figure 3.

Molecular phenotype of TGFβ1-treated hMSCs. (a) Hierarchical clustering of genes that were differentially expressed in TGFβl-treated and untreated control (CNT) hMSCs. Rows represent individual gene expression for duplicate treated and untreated samples, as indicated. Columns represent individual transcripts. Relative expression levels are presented colorimetrically, according to the scale shown in the color bar. (b) Pie chart showing the pathways with the highest enrichment of genes significantly upregulated in TGFβ1-treated cells. (c) qRT-PCR validation of selected genes that were upregulated in the microarray data (n = 3, ∗ p < 005; ∗∗∗ p < 0001). Cells treated with vehicle (DMSO) were used as controls.

Table 1.

Osteogenesis- and adipogenesis-related genes, from the most enriched pathways, that are upregulated in TGFβ1-treated cells.

| Endochondral ossification | Actin cytoskeleton | Focal adhesion | TGFβ signaling | MAPK signaling | Adipogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEGFA | FGF2 | COL11A1 | SMURF1 | MAPK8 | FOXO1A |

| ADAMTS4 | FGFR1 | COL3A1 | MAPK8 | NGFB | TRIB3 |

| PLAT4 | TMSB4X | COL4A1 | SKP1 | PDGFRB | PCK2 |

| COL10A1 | GNA13 | COL4A2 | NEDD9 | RASA2 | EGR2 |

| TGFB2 | PDGFA | COL4A4 | ETS1 | SOS2 | DDIT3 |

| PTHrP | FGF1 | COL5A1 | KLF11 | KRAS | GADD45A |

| FGF2 | ENAH | COL5A2 | ATF3 | MRAS | GADD45B |

| C4ST1 | MSN | COL1A1 | FOSB | NF1 | HIF1A |

| FGFR1 | GSN | LAMC2 | SKIL | RAP1B | IRS1 |

| PDGFRB | PDGFRB | THBS2 | SMURF1 | DUSP1 | MEF2D |

| COL1 | KRAS | CAV2 | ZFYVE16 | DDIT3 | FAS |

| MRAS | ARHGAP5 | HSPB1 | SPOCK | ||

| SOS2 | PTEN | IL1A | |||

| AKT3 | FAS | ||||

| PDGFA | TGFB2 | ||||

| PDGFC | MAP313 | ||||

| PGF | ZAK | ||||

| ITGA2 | AKT3 | ||||

| PDGFRB | MAP3K8 | ||||

| RAP1B | GADD45A | ||||

| MAPK8 |

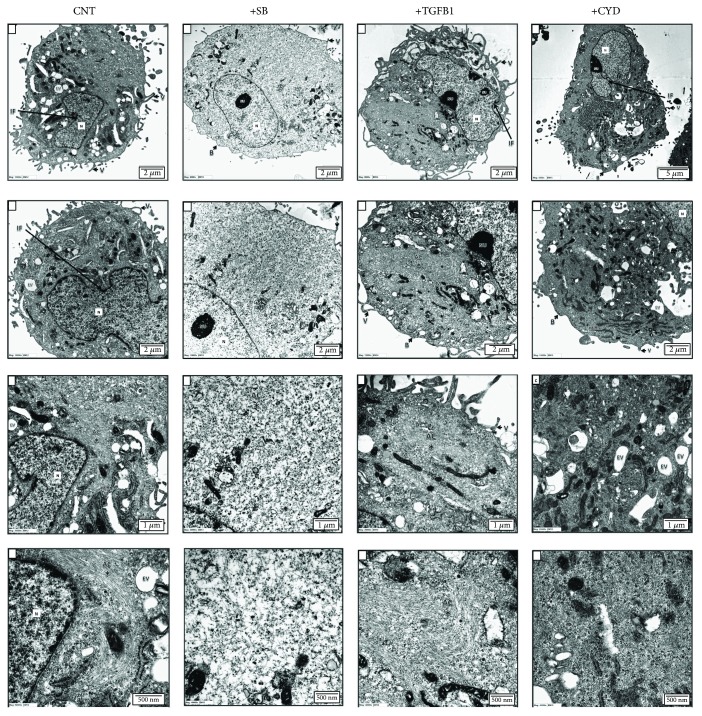

2.5. Actin Microfilaments in MSCs Are Altered following Treatment with TGFβ1 or the Actin Polymerization Inhibitor CYD

Our molecular phenotyping analysis of TGFβl-treated hMSCs revealed a significant enrichment of genes associated with cytoskeletal changes. Based on this, and on our previous observations that TGFβl treatment triggers significant morphological changes in hMSCs, we examined the effect of TGFβl on the cytoskeleton using transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which has the power to reveal structural changes in actin microfilaments. Actin microfilament polymerization was found to be inhibited in cells treated with either the potent actin polymerization inhibitor CYD or the TGFβ inhibitor SB-431542. In contrast, TGFβ1 treatment was associated with a prominent distribution of actin filaments, organized as bundles/aggregates, in the perinuclear area and at one cell pole (Figure 4). The ultrastructural characteristics of the cells under the various treatment conditions are summarized in Supplementary Table S4.

Figure 4.

Transmission electron microscopy of MSCs with and without treatment with SB-431542, TGFβ1, or CYD. TEM ultrastructural analysis of MSCs following no treatment (CNT) or treatment with SB-431542 (SB), TGFβ1, or CYD. Increasing levels of magnification are indicated by scale bars. N: nucleus; Nu: nucleolus; AC: actin filaments; V: microvilli; M: mitochondria; PL: primary lysosome; SL: secondary lysosome; rER: rough endoplasmic reticulum; G: Golgi bodies; B: cell blebs; P: cell processes; IF: nuclear membrane infolding; EV: endocytotic vacuole.

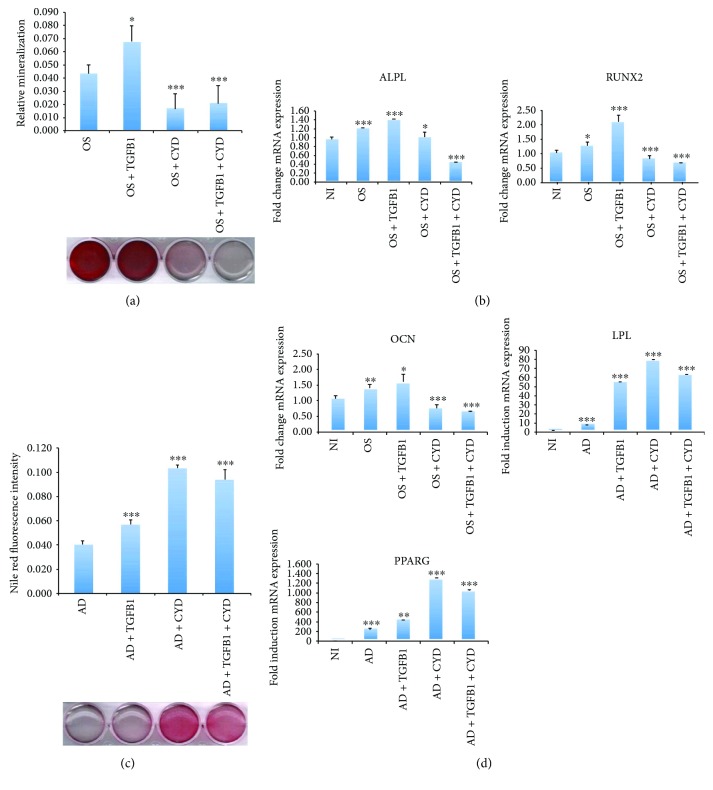

2.6. CYD Regulates Osteogenic and Adipogenic Differentiation in the Presence of TGFβ1

To confirm that TGFβ1 regulates actin cytoskeletal dynamics, hMSCs undergoing either osteogenic or adipogenic differentiation were treated with TGFβ1 in the absence or presence of the actin polymerization inhibitor CYD. CYD treatment significantly inhibited hMSC osteogenic differentiation in both the presence and absence of TGFβl, as shown by reduced mineralization (Figure 5(a)). Similarly, expression of the osteogenic marker genes ALPL, RUNX2, and OCN was inhibited by CYD treatment, with and without TGFβl (Figure 5(b)). Conversely, CYD treatment enhanced hMSC adipogenic differentiation, as shown by a greatly increased number of lipid-filled mature adipocytes and the increased expression of the adipogenic marker genes LPL and PPARG-2. These effects were maintained when cells were treated concomitantly with TGFβl (Figures 5(c) and 5(d)).

Figure 5.

Inhibition of actin polymerization promotes adipogenic differentiation but inhibits osteogenic differentiation in MSCs. MSCs underwent osteogenic or adipogenic differentiation by culturing cells in the appropriate medium for 7 days. Cells also underwent the indicated treatments. (a) Mineralized calcium deposition, as determined by alizarin red S staining in MSCs that were osteoinduced (OS), osteoinduced with TGFβ1 treatment two days prior to induction (OS + TGFβ1), osteoinduced with CYD treatment at the onset of induction (OS + CYD), or osteoinduced with both TGFβ1 and CYD treatment at the time points described above (OS + TGFβ1 + CYD). Lower panel: micrograph of stained wells. Upper panel: quantification of mineralized matrix formation under the indicated treatment conditions. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (∗ p < 0.05; ∗∗∗ p < 0.005). (b) Gene expression of the osteogenic markers ALPL, RUNX2, and OCN, normalized to GAPDH, as determined by qRT-PCR. Cells were either not induced (NI) or induced under the conditions described in (a). Data are shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (∗ p < 0.05; ∗∗ p < 0.005, ∗∗∗ p < 0.0005). (c) Adipogenic differentiation of MSCs that were adipoinduced (AD), adipoinduced with TGFβ1 treatment 2 days prior to induction (AD + TGFβ1), adipoinduced with CYD treatment, initiated at the onset of induction (AD + CYD), or adipoinduced with both TGFβ1 and CYD treatment at the time points described above (AD + TGFβ1 + CYD). Lower panel: Oil red O staining of the indicated cells. Upper panel: Nile red quantification of oil content under the indicated conditions. (d) Gene expression of the adipogenic marker genes PPARG and LPL, determined by qRT-PCR and normalized to GAPDH, under the indicated treatment regimens. Data are shown as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments (∗∗ p < 0.005, ∗∗∗ p < 0.0005). All controls were treated with vehicle only.

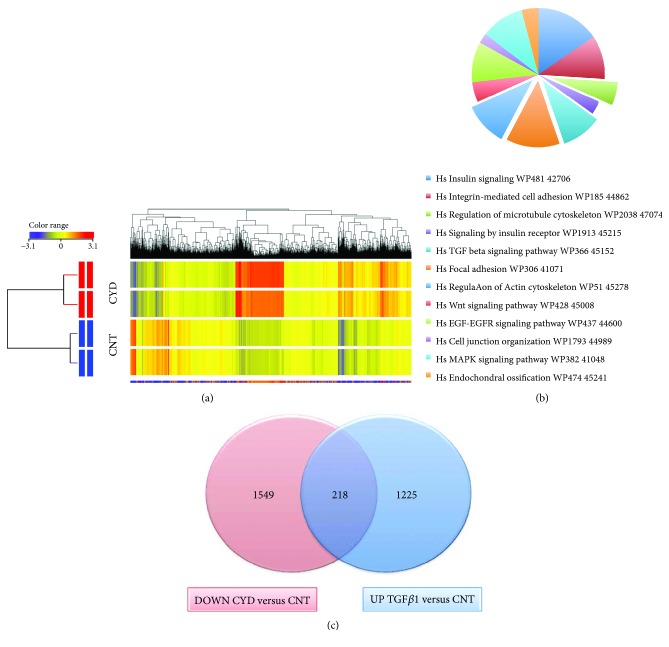

2.7. Molecular Phenotype of CYD-Treated Cells

The data presented above suggest that CYD and TGFβ1 target similar molecular pathways during hMSC osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation. In order to investigate this further and to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the CYD-mediated effects on hMSC differentiation, microarray analysis was performed to establish global gene expression profiles for CYD-treated and controls cells. In total, 10,855 genes were significantly upregulated, and 2523 genes were significantly downregulated following CYD treatment. Genes were defined as significantly changed if they had a fold change ≥ 2 and p < 0.05 and are listed in Supplementary Tables S5 and S6. As was seen with TGFβ1 treatment, hierarchical clustering of the differentially expressed genes revealed a clear distinction between untreated and CYD-treated hMSCs (Figure 6(a)). Pathway analysis of these genes revealed several molecular pathways that were enriched upon CYD treatment (Figure 6(b)). Among the most significant were pathways involved in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton, focal adhesion signaling, endochondral ossification, TGFβ1 signaling, regulation of the microtubule cytoskeleton, and MAPK signaling (Figure 6(b)). The genes that are associated with these pathways that were upregulated in CYD-treated cells are listed in Table 2. Forty-two genes that are involved in adipogenesis-related pathways were significantly enriched in CYD-treated cells (Table 3). Interestingly, 218 genes were both upregulated in TGFβ1-treated hMSCs and downregulated in CYD-treated hMSCs (Figure 6(c)), showing that the molecular signature on CYD treatment is the inverse of that seen with TGFβ1 treatment and suggesting that these genes may be involved in TGFβ-mediated cytoskeletal reorganization (Table 4).

Figure 6.

Molecular phenotype of CYD-treated hMSCs. (a) Hierarchical clustering of genes that were differentially expressed in CYD-treated and untreated control (CNT) hMSCs. Rows represent individual gene expression for duplicate treated and untreated samples, as indicated. Columns represent individual transcripts. Relative expression levels are presented colorimetrically, according to the scale shown in the color bar. (b) Pie chart showing the pathways with the highest enrichment of genes significantly upregulated in CYD-treated cells. (c) Venn diagram depicting the overlap between the upregulated genes in TGFβ1-treated cells (UP TGFβ1 versus CNT) and the downregulated genes in CYD-treated cells (DOWN CYD versus CNT).

Table 2.

Genes involved in osteogenesis-related pathways that are downregulated in CYD-treated hMSCs.

| Endochondral ossification | Actin cytoskeleton | Focal adhesion | TGFβ signaling | MAPK signaling |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FGF2 | FGF1 | ITGA6 | UCHL5 | STMN1 |

| TGFB2 | FGF2 | STYK1 | CDC2 | DUSP1 |

| PLAT | FGF5 | CAV1 | SMURF2 | TRAF2 |

| CALM1 | FGF22 | CAV2 | NEDD9 | BDNF |

| ADAMTS1 | KRAS | CAV3 | STAMBPL1 | MAP3K5 |

| OPG | NRAS | LAMC2 | CCNB2 | ACVR1C |

| C11orf13 | THBS1 | RBL1 | KRAS | |

| F2R | PXN | MAPK8 | TGFB2 | |

| CRK | RHOB | PARD6A | NRAS | |

| PAK1 | PDPK1 | CAV1 | PPP5C | |

| ARHGEF7 | MYLK2 | TFDP1 | PAK1 | |

| VIL2 | PAK1 | KLF6 | CRK | |

| PXN | MAPK8 | FST | MAPK8 | |

| BCL2 | SERPINE1 | |||

| CCND3 | THBS1 | |||

| CRK | NOG | |||

| HRAS |

Table 3.

Genes involved in adipogenesis-related pathways that are upregulated in CYD-treated hMSCs.

| Gene symbol | Fold change versus control |

|---|---|

| PPARGC1A | 2.4170778 |

| AGT | 15.447543 |

| GDF10 | 9.77814 |

| BMP2 | 9.539022 |

| UCP1 | 9.416412 |

| SFRP4 | 6.513523 |

| IRS4 | 5.973821 |

| MEF2C | 5.1696005 |

| LPL | 5.150721 |

| PLIN1 | 5.144724 |

| LEP | 5.1005282 |

| NDN | 5.0982733 |

| CNTFR | 4.9715867 |

| LIF | 3.9070668 |

| PRLR | 3.855135 |

| RXRG | 3.8392398 |

| EGR2 | 3.6894956 |

| PCK1 | 3.6815107 |

| CYP26A1 | 3.170688 |

| TGFBI | 3.1407108 |

| STAT2 | 3.0656292 |

| BMP3 | 2.9982927 |

| IGF1 | 2.9808753 |

| PTGIS | 2.8547947 |

| INSR | 2.8151898 |

| SLC2A4 | 2.747039 |

| CEBPB | 2.7001002 |

| IRS1 | 2.5992496 |

| LPIN1 | 2.579549 |

| AHRR | 2.5087466 |

| IL6 | 2.4654725 |

| IRS2 | 2.3497624 |

| STAT5A | 2.2441745 |

| CEBPA | 2.2439373 |

| SCD | 2.216643 |

| STAT1 | 2.205384 |

| SPOCK1 | 2.201062 |

| SREBF1 | 2.0996578 |

| EPAS1 | 2.0842645 |

| MEF2D | 2.0606902 |

| BMP1 | 2.0168457 |

| LPIN3 | 2.0103807 |

Table 4.

Genes involved in both osteogenesis- and adipogenesis-related pathways that are significantly changed in TGFβ-treated cells and CYD-treated cells.

| Endochondral ossification | Actin cytoskeleton | Focal adhesion | TGFB signaling | MAPK signaling | Adipogenesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFB2 | FGF1 | CAV2 | NEDD9 | TGFB2 | EGR2 |

| FGF2 | FGF2 | MAPK8 | MAPK8 | MAPK8 | IRS1 |

| PLAT | KRAS | LAMC2 | KRAS | MEF2D | |

| DUSP1 |

3. Discussion

TGFβ is a potent regulator of various biological functions in many cell types, but its effects on hMSC differentiation are, to date, poorly understood. In the present study, we contribute to this understanding and demonstrate that TGFβ can enhance both osteoblastic and adipocytic lineage commitment by modulating changes to the actin cytoskeleton.

TGFβ1 is known to regulate the proliferation and differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells [6, 13–15], and it reportedly stimulates bone matrix apposition and bone cell replication [16]. Several studies have demonstrated that TGFβ1 promotes bone formation in vitro by recruiting osteoblast progenitors and inducing bone matrix formation at early stages of differentiation. In addition to this direct regulation of bone formation, TGFβ1, along with BMPs, enhances RUNX2 expression at early differentiation stages [17]. This is consistent with our finding that TGFβ1 promoted osteogenesis and was associated with the upregulation of the osteogenic genes ALPL, RUNX2, and OCN.

Furthermore, we showed that TGF-β1 treatment enhanced the in vitro adipocytic differentiation of hMSCs. This is consistent with several previously reported studies which demonstrate that TGFβ1 has a positive effect on adipogenic differentiation under specific culture conditions [18, 19]; an early study considering rat brown adipocytes showed an upregulation of lipogenic enzymes following TGFβ1 treatment [19].

Our results showed that TGFβ1 treatment did not affect MSC cell growth in vitro. Previously, conflicting results have been published; some studies reported that TGFβ1 regulated osteoprogenitor proliferation in vitro [13, 20], whereas Yu et al. reported that TGFβ1 treatment strongly inhibited the proliferation of human lung epithelial cells [21]. The mitogenic effects of TGFβ on cells are reportedly variable; while progressive mitogenesis was stimulated in confluent cells following treatment with 0.15–15 ng/ml TGFβ, in sparse cultures 0.15 ng/ml TGFβ exhibited inhibitory effects. However, at all cell densities, 15 ng/ml TGFβ stimulated collagen synthesis, with this effect being most pronounced when DNA synthesis was declining [22]. Most of the published data on TGFβ has shown a mitogenic effect on osteoprogenitors [16, 23–26], but relatively few studies have examined the growth inhibitory effect of this cytokine on osteoblast-like cells [27, 28]. It is likely that these contradictory observations reflect the fact that the effect TGFβ has on cellular proliferation is dependent upon TGFβ concentration, culture conditions including cell density, the cell model system (tumorigenic versus nontumorigenic), the differentiation stage of the target cell population, and/or the presence of other growth factors.

The cytoskeleton is known to be important for cell morphology and for mediating changes in adhesion and differentiation [11]. Furthermore, significant changes in cytoskeletal components reportedly occur during hMSC lineage commitment and differentiation [7, 11]. While changes in cell shape can be influenced by differentiation, several studies have shown that the differentiation of precommitted mesenchymal stem cells is itself influenced by changes in cellular morphology resulting from the altered expression of cadherins, integrins, and cytoskeletal proteins [29]. Recently, the inhibition of actin depolymerization was shown to enhance both hMSC differentiation into osteoblasts and in vivo bone formation, with these effects being mediated by several signaling pathways and involving focal adhesion kinase (FAK), p38, and JNK activation [7]. Furthermore, a separate study reported that the suppression of actin polymerization, a very early event in hMSC differentiation, following the downregulation of p38 MAPK activity, inhibited osteogenesis [30]. Additionally, α-smooth muscle actin is important for both the identification of osteoprogenitors in hMSCs and their differentiation fate [31], and Rho GTPase-mediated cytoskeletal modification is essential for controlling hMSC differentiation and migration [32].

On the other hand, adipocytic differentiation is associated with the morphological change from fibroblast-like cells to spherical cells filled with fat droplets [33]. These morphological alterations are also associated with cytoskeletal changes and actin reorganization, which takes place in the early lineage commitment stage, prior to the upregulation of many adipocytic-specific gene markers [34]. The differentiation of hMSCs into the adipocytic lineage in vitro is known to be influenced by the cytoskeletal tension that results following actin reorganization [32]. Furthermore, TGFβ1 Ca2+ signaling is known to regulate osteoblast adhesion through enhanced α5 integrin expression, the formation of focal contacts, and the mediation of cytoskeleton reorganization [35, 36]. Additionally, the TGFβ1-mediated stimulation of DNA synthesis in mouse osteoblastic cells is reportedly associated with morphological changes and is accompanied by the enhanced synthesis and polymerization of cytoskeletal proteins [37]. Consistent with this, our data suggests that TGFβ1 enhances hMSC lineage commitment by regulating the morphology of the actin cytoskeleton, focal adhesion, and endochondral ossification, via the TGFβ1 and MAPK signaling pathways.

Also consistent with our results are reports that CYD-mediated reductions in actin polymerization stimulate adipogenesis, but inhibit osteogenesis [30], suggesting that cytoskeletal modification is a prerequisite for cell fate determination. Our gene expression profiling revealed that the genes FGF1, FGF2, and KRAS, which commonly regulate actin cytoskeleton reorganization, were upregulated and downregulated in TGFβ1- and CYD-treated cells, respectively, suggesting that they are involved in the actin polymerization-mediated differentiation of MSCs.

We showed that during osteogenesis, TGFβ1 treatment reorganized the cytoskeleton, but this reorganization, and thus osteogenesis, could be disturbed by CYD treatment. Conversely, treatment with either TGFβ1 or CYD promoted adipogenesis. This observation can potentially be explained by considering that TGFβ1 and CYD promote the formation of different cytoskeleton patterns, both of which support adipogenesis. Alternatively, it is possible that cytoskeletal reorganization leading to adipogenesis can be promoted by both TGFβ1-dependent and -independent mechanisms, and that CYD-mediated cytoskeletal reorganization cannot override the TGFβ1-independent mechanism.

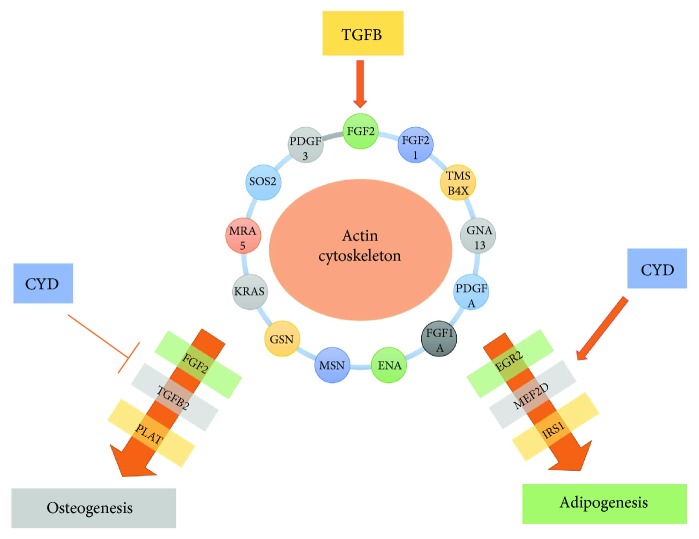

We propose a model wherein TGFβ1 regulates cytoskeletal organization by modulating actin cytoskeleton-related genes, leading to enhanced hMSC differentiation into both osteoblasts and adipocytes (Figure 7). We propose that CYD enhances adipogenesis and inhibits osteogenesis by regulating the expression of a number of key candidate genes, including FGF2, TGFβ2, Plat, EGR2, MEF2D, and IRS1. These genes were modulated by both TGFβ1 and CYD and are thus heavily implicated in the determination of hMSC fate. In summary, our study provides novel molecular insights into the role of the intracellular TGFβ signaling pathway in bone and bone marrow adipose tissue formation. This signaling involves the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton in order to control the lineage-specific differentiation of hMSCs.

Figure 7.

TGFβ1 signaling in hMSC differentiation. Schematic showing how TGFβ and CYD affect hMSC osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation through the modulation of genes associated with the actin cytoskeletal pathway. Suggested downstream targets are also shown.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Cell Culture

An hMSC-TERT cell line was created previously to serve as a model of human primary MSCs by overexpressing human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) in normal human bone marrow MSCs [38]. This cell line has been extensively characterized and exhibits a similar cellular and molecular phenotype to primary MSCs [39]. For the current experiments, we used a previously characterized subline derived from hMSC-TERT cells, termed hMSC-TERT-CL1 [40]. For ease, this cell line is referred to as “hMSC” for the remainder of the manuscript. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 4500 mg/l D-glucose, 4 mM L-glutamine, 110 mg/l sodium pyruvate, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1× penicillin/streptomycin (pen/strep), and nonessential amino acids. All reagents were purchased from Gibco, USA.

4.2. In Vitro Osteoblastic Differentiation

To induce osteoblastic differentiation, cells were initially grown in standard DMEM growth medium in 6-well plates at a density of 0.3 × 106 cells/ml. Once 70–80% confluence was reached, the medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with osteoblast induction mixture, containing 10% FBS, 1% pen/strep, 50 μg/ml L-ascorbic acid (Wako Chemicals, Neuss, Germany), 10 mM β-glycerophosphate (Sigma), 10 nM calcitriol (1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3; Sigma), and 10 nM dexamethasone (Sigma). The medium was replaced 3 times per week. Cells were cultured in standard culture medium in parallel as controls.

4.3. In Vitro Adipocytic Differentiation

To induce adipocytic differentiation, cells were initially grown in standard DMEM growth medium in 6-well plates at a density of 0.3 × 106 cells/ml. Once 90–100% confluence was reached, the medium was replaced with DMEM supplemented with adipogenic induction mixture, containing 10% FBS, 10% horse serum (Sigma), 1% pen/strep, 100 nM dexamethasone, 0.45 mM isobutyl methylxanthine [41] (Sigma), 3 μg/ml insulin (Sigma), and 1 μM rosiglitazone [42] (Novo Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark). The medium was replaced 3 times per week, and cells cultured in parallel in standard culture medium were used as controls.

4.4. Cytochemical Staining

4.4.1. Alizarin Red S Staining for Mineralized Matrix

Once cells had grown sufficiently, the cell monolayer was washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then rinsed 3 times in distilled water and stained with 2% alizarin red S Stain (Cat. number 0223; ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 20–30 minutes at room temperature. Cells were washed further 3–5 times with water to remove excess dye and then stored in water to prevent them drying out. Cells were then visualized using an inverted microscope (ZEISS AX10). To quantify alizarin red S staining, and hence mineralization, plates were air dried, and then the alizarin red S dye was eluted by adding 800 μl acetic acid to each well and incubating for 30 minutes at room temperature, as described previously [43]. The stain was then quantified by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm with an Epoch spectrophotometer (BioTek Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

4.4.2. OsteoImage Mineralization Assay

The formation of mineralized matrix in vitro was quantified using an OsteoImage mineralization assay kit according to manufacturer's instructions (Cat. number PA-1503; Lonza, USA). Briefly, culture medium was removed, and cells were washed once with PBS and then fixed with 70% cold ethanol for 20 minutes. Next, diluted staining reagent was added at a level recommended by the manufacturer, and plates were incubated in the dark for 30 minutes at room temperature. The cells were then washed, and staining was quantified using a fluorescence plate reader (Molecular Devices Co., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 492 and 520 nm, respectively.

4.4.3. Oil Red O Staining for Lipid Droplets

Cytoplasmic lipid droplets within mature adipocytes were visualized using Oil red O staining. Cells were washed with PBS, fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature, rinsed once with 3% isopropanol, and then stained for 1 hour at room temperature with filtered Oil red O staining solution (prepared by dissolving 0.5 g Oil red O powder in 60% isopropanol). In order to quantify mature adipocytes, Oil red O stain was eluted from cells by adding 100% isopropanol to each well, and then the absorbance at 510 nm was measured using an Epoch spectrophotometer.

4.4.4. Nile Red Staining for the Quantification of Mature Adipocytes

A 1 mg/ml stock solution of Nile red fluorescent stain was prepared in DMSO and stored in the dark at −20°C. Cultured undifferentiated and differentiated cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) for 15 minutes and then washed once with PBS. PBS was then removed, and cells were stained with 5 μg/ml Nile red stain in PBS for 10 minutes at room temperature. The fluorescence signal was measured using a SpectraMax/M5 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices Co.) in bottom-well scan mode. Nine readings were taken per well using excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 nm and 572 nm, respectively.

4.5. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using a PureLink RNA mini kit (Cat number 12183018A; Ambion, USA) according to manufacturer's recommendations and quantified using a NanoDrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) was synthesized from 1 μg RNA using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, USA) and a MultiGene thermal cycler (Labnet) according to manufacturer's instructions. Relative mRNA levels were inferred from the cDNAs using Power SYBR Green master mix (Applied Biosystems, UK) and TaqMan Universal master mix II, no UNG (Applied Biosystems, USA), both according to manufacturer's instructions, and a real-time PCR detection system (Applied Biosystems). Relative mRNA levels were normalized to the reference gene GAPDH, and then gene expression quantification was performed using a comparative Ct method, wherein ΔCT is defined as the difference between the target and reference gene CT values. Primers are listed in Supplementary Tables S7 and S8. These primers were either TaqMan primers (Applied Biosystems) or custom primers whose sequences have been published previously.

4.6. Global Gene Expression Profiling by Microarray

Total RNA was extracted from cells using a PureLink RNA mini kit, according to manufacturer's recommendations. One hundred and fifty nanograms of total RNA was then labeled and hybridized to a SurePrint G3 Human GE 8 × 60 K microarray chip (Agilent Technologies). All microarray experiments were conducted by the Microarray Core Facility (Stem Cell Unit, College of Medicine, King Saud University). Normalization and data analyses were performed using GeneSpring GX software (Agilent Technologies), and pathway analysis was conducted using the Single Experiment Pathway analysis feature of the GeneSpring 12.0 software package (Agilent Technologies) as described previously (66). In addition, we used the web-based software DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8, where all genes that were upregulated by TGfb were uploaded into DAVID and signaling pathways were achieved. Significant changes were defined as a fold change of ≥2 and p < 0.02.

4.7. Cell Proliferation Assays

4.7.1. AlamarBlue Cell Viability Assay

Cell viability was measured using alamarBlue assay reagent (AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC, USA) according to manufacturer's recommendations. Briefly, cells were cultured in 96-well plates in 100 μl of the appropriate medium before 10 μl alamarBlue substrate was added at the indicated time points. Plates were then incubated in the dark at 37°C for 1 hour. AlamarBlue fluorescence was then detected using a Synergy II microplate reader (BioTek Inc.) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 530 nm and 590 nm, respectively.

4.8. RTCA Cell Proliferation Assay

An xCELLigence RTCA (real-time cell analysis) DP system (ACEA Biosciences Inc., San Diego, CA) was used to measure the rate of cellular proliferation according to manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 100 μl DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS was loaded onto each well of an E-plate 16 chamber slide, which was then placed inside the humidified incubator of the RTCA DP analyzer for 1 hour at 37°C to allow the membrane surface and medium to equilibrate. After 1 hour, background measurements were performed. Next, 5000 cells/100 μl DMEM + 10% FBS were added per well, and measurements were recorded at 15-minute intervals for various total durations, depending on the experimental setup.

4.9. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

For TEM, cells were trypsinized, washed with PBS, pelleted, and then fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Cat. number 16500; Electron Microscopy Sciences) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) at 4°C for 4 hours. Next, the cells were washed in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) 3 times for 30 minutes each and then treated with 1% osmium tetroxide (OsO4) in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) for 2 hours. Cells were then dehydrated in increasing concentrations of ethanol (10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, and 100%) for 15 minutes each, before being resuspended in acetone and incubated for 15 minutes. The resulting cell suspension was then aliquoted into BEEM® embedding capsules and infiltrated firstly with a 2 : 1 acetone : resin mixture for 1 hour and secondly with a 1 : 2 acetone : resin mixture for 1 hour. Following infiltration, the BEEM capsules were centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 minutes and embedded in pure resin for 2 hours. The resin was then polymerized by baking in an oven at 70°C for 12 hours. Semithin sections (0.5 μm thickness) were prepared and stained with 1% toluidine blue. Ultrathin sections (70 nm thickness) were prepared and mounted on copper grids and then stained firstly with uranyl acetate (saturated ethanol solution) for 30 minutes, rinsed with double distilled water and then stained with Reynold's lead citrate solution for 5 minutes before a final rinse with distilled water. The contrasted ultrathin sections were examined and photographed under a JEOL 1010 transmission electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan).

4.10. Statistical Analysis

All results are presented as the mean ± SD of at least 3 independent experiments. Differences between groups were assessed using Student's t-test, and p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to extend their sincere appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University for its funding of this research through the Research Group Project no. RGP-1438-032.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: DAVID microarray functional gene analysis. One thousand nine hundred genes were uploaded to DAVID online software. KEGG pathway analysis showed many interested pathways which are upregulated after TGFb-1 treatment of hBMCs. Here, we show the top most upregulated pathways which include key osteoblast differentiation pathways.

Table S1: whole genome microarray mRNA data showing gene ENTITIES for TG1 versus CNT DOWN 1298 genes.

Table S2: whole genome microarray mRNA data showing gene ENTITIES for TG1 versus CNT UP 1932 genes.

Table S3: upregulated biological processes and related genes in TGFB1-treated cells using GO analysis.

Table S4: ultrastructural characteristics of CL1 cells under different treatment conditions.

Table S5: whole genome microarray mRNA data showing gene entities for CYD versus CNT up to 10,855 genes.

Table S6: whole genome microarray mRNA data showing gene entities for CYD versus CNT DOWN 2523 genes.

Table S7: real-time PCR human primer sequences used in this study.

Table S8: TAQMAN real-time PCR primers.

References

- 1.Oshimori N., Fuchs E. The harmonies played by TGF-β in stem cell biology. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11(6):751–764. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massagué J., Seoane J., Wotton D. Smad transcription factors. Genes & Development. 2005;19(23):2783–2810. doi: 10.1101/gad.1350705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pfeilschifter J., Bonewald L., Mundy G. R. Characterization of the latent transforming growth factor ß complex in bone. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1990;5(1):49–58. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650050109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheppard D. Transforming growth factor β: a central modulator of pulmonary and airway inflammation and fibrosis. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2006;3(5):413–417. doi: 10.1513/pats.200601-008AW. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang Y., Wu X., Lei W., et al. TGF-β1–induced migration of bone mesenchymal stem cells couples bone resorption with formation. Nature Medicine. 2009;15(7):757–765. doi: 10.1038/nm.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janssens K., ten Dijke P., Janssens S., Van Hul W. Transforming growth factor-β1 to the bone. Endocrine Reviews. 2005;26(6):743–774. doi: 10.1210/er.2004-0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L., Shi K., Frary C. E., et al. Inhibiting actin depolymerization enhances osteoblast differentiation and bone formation in human stromal stem cells. Stem Cell Research. 2015;15(2):281–289. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ono S. Mechanism of depolymerization and severing of actin filaments and its significance in cytoskeletal dynamics. International Review of Cytology. 2007;258:1–82. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(07)58001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lappalainen P., Drubin D. G. Cofilin promotes rapid actin filament turnover in vivo . Nature. 1997;388(6637):78–82. doi: 10.1038/40418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fletcher D. A., Mullins R. D. Cell mechanics and the cytoskeleton. Nature. 2010;463(7280):485–492. doi: 10.1038/nature08908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yourek G., Hussain M. A., Mao J. J. Cytoskeletal changes of mesenchymal stem cells during differentiation. ASAIO Journal. 2007;53(2):219–228. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e31802deb2d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elsafadi M., Manikandan M., Dawud R. A., et al. Transgelin is a TGFβ-inducible gene that regulates osteoblastic and adipogenic differentiation of human skeletal stem cells through actin cytoskeleton organization. Cell Death & Disease. 2016;7(8, article e2321) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jian H., Shen X., Liu I., Semenov M., He X., Wang X. F. Smad3-dependent nuclear translocation of β-catenin is required for TGF-β1-induced proliferation of bone marrow-derived adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Genes & Development. 2006;20(6):666–674. doi: 10.1101/gad.1388806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erlebacher A., Filvaroff E. H., Ye J. Q., Derynck R. Osteoblastic responses to TGF-β during bone remodeling. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1998;9(7):1903–1918. doi: 10.1091/mbc.9.7.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filvaroff E., Erlebacher A., Ye J., et al. Inhibition of TGF-beta receptor signaling in osteoblasts leads to decreased bone remodeling and increased trabecular bone mass. Development. 1999;126(19):4267–4279. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.19.4267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hock J. M., Canalis E., Centrella M. Transforming growth factor-β stimulates bone matrix apposition and bone cell replication in cultured fetal rat calvariae. Endocrinology. 1990;126(1):421–426. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-1-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spinella-Jaegle S., Roman-Roman S., Faucheu C., et al. Opposite effects of bone morphogenetic protein-2 and transforming growth factor-β1 on osteoblast differentiation. Bone. 2001;29(4):323–330. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(01)00580-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ignotz R. A., Massagué J. Type beta transforming growth factor controls the adipogenic differentiation of 3T3 fibroblasts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1985;82(24):8530–8534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.24.8530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teruel T., Valverde A. M., Benito M., Lorenzo M. Transforming growth factor β 1 induces differentiation-specific gene expression in fetal rat brown adipocytes. FEBS Letters. 1995;364(2):193–197. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00385-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maeda S., Hayashi M., Komiya S., Imamura T., Miyazono K. Endogenous TGF-β signaling suppresses maturation of osteoblastic mesenchymal cells. The EMBO Journal. 2004;23(3):552–563. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu H., Königshoff M., Jayachandran A., et al. Transgelin is a direct target of TGF-β/Smad3-dependent epithelial cell migration in lung fibrosis. The FASEB Journal. 2008;22(6):1778–1789. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-083857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centrella M., McCarthy T. L., Canalis E. Transforming growth factor beta is a bifunctional regulator of replication and collagen synthesis in osteoblast-enriched cell cultures from fetal rat bone. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1987;262(6):2869–2874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robey P. G., Young M. F., Flanders K. C., et al. Osteoblasts synthesize and respond to transforming growth factor-type beta (TGF-beta) in vitro. The Journal of Cell Biology. 1987;105(1):457–463. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.1.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen T. L., Bates R. L. Recombinant human transforming growth factor β 1 modulates bone remodeling in a mineralizing bone organ culture. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 1993;8(4):423–434. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamada T., Kamiya N., Harada D., Takagi M. Effects of transforming growth factor-β1 on the gene expression of decorin, biglycan, and alkaline phosphatase in osteoblast precursor cells and more differentiated osteoblast cells. The Histochemical Journal. 1999;31(10):687–694. doi: 10.1023/A:1003855922395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kassem M., Kveiborg M., Eriksen E. F. Production and action of transforming growth factor-β in human osteoblast cultures: dependence on cell differentiation and modulation by calcitriol. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2000;30(5):429–437. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2000.00645.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noda M., Rodan G. A. Type β transforming growth factor (TGFβ) regulation of alkaline phosphatase expression and other phenotype-related mRNAs in osteoblastic rat osteosarcoma cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1987;133(3):426–437. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041330303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antosz M. E., Bellows C. G., Aubin J. E. Effects of transforming growth factor β and epidermal growth factor on cell proliferation and the formation of bone nodules in isolated fetal rat calvaria cells. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 1989;140(2):386–395. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041400225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gumbiner B. M. Cell adhesion: the molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell. 1996;84(3):345–357. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sonowal H., Kumar A., Bhattacharyya J., Gogoi P. K., Jaganathan B. G. Inhibition of actin polymerization decreases osteogeneic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells through p38 MAPK pathway. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2013;20(1):p. 71. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-20-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talele N. P., Fradette J., Davies J. E., Kapus A., Hinz B. Expression of α-smooth muscle actin determines the fate of mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4(6):1016–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McBeath R., Pirone D. M., Nelson C. M., Bhadriraju K., Chen C. S. Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment. Developmental Cell. 2004;6(4):483–495. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fan J. Y., Carpentier J. L., van Obberghen E., Grunfeld C., Gorden P., Orci L. Morphological changes of the 3T3-L1 fibroblast plasma membrane upon differentiation to the adipocyte form. Journal of Cell Science. 1983;61:219–230. doi: 10.1242/jcs.61.1.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Antras J., Hilliou F., Redziniak G., Pairault J. Decreased biosynthesis of actin and cellular fibronectin during adipose conversion of 3T3-F442A cells. Reorganization of the cytoarchitecture and extracellular matrix fibronectin. Biology of the Cell. 1989;66(3):247–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1768-322X.1989.tb00841.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nesti L. J., Caterson E. J., Wang M., et al. TGF-β1-stimulated osteoblasts require intracellular calcium signaling for enhanced α5 integrin expression. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2002;961(1):178–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb03078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nesti L. J., Caterson E. J., Wang M., et al. TGF-β1 calcium signaling increases α5 integrin expression in osteoblasts. Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 2002;20(5):1042–1049. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lomri A., Marie P. J. Effects of transforming growth factor type β on expression of cytoskeletal proteins in endosteal mouse osteoblastic cells. Bone. 1990;11(6):445–451. doi: 10.1016/8756-3282(90)90141-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Simonsen J. L., Rosada C., Serakinci N., et al. Telomerase expression extends the proliferative life-span and maintains the osteogenic potential of human bone marrow stromal cells. Nature Biotechnology. 2002;20(6):592–596. doi: 10.1038/nbt0602-592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Al-Nbaheen M., Vishnubalaji R., Ali D., et al. Human stromal (mesenchymal) stem cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue and skin exhibit differences in molecular phenotype and differentiation potential. Stem Cell Reviews. 2013;9(1):32–43. doi: 10.1007/s12015-012-9365-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elsafadi M., Manikandan M., Atteya M., et al. Characterization of cellular and molecular heterogeneity of bone marrow stromal cells. Stem Cells International. 2016;2016:18. doi: 10.1155/2016/9378081.9378081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hildebrand A., Romarís M., Rasmussen L. M., et al. Interaction of the small interstitial proteoglycans biglycan, decorin and fibromodulin with transforming growth factor β . The Biochemical Journal. 1994;302(2):527–534. doi: 10.1042/bj3020527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serra R., Chang C. TGF-β signaling in human skeletal and patterning disorders. Birth Defects Research Part C: Embryo Today: Reviews. 2003;69(4):333–351. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.10023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gregory C. A., Gunn W. G., Peister A., Prockop D. J. An alizarin red-based assay of mineralization by adherent cells in culture: comparison with cetylpyridinium chloride extraction. Analytical Biochemistry. 2004;329(1):77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1: DAVID microarray functional gene analysis. One thousand nine hundred genes were uploaded to DAVID online software. KEGG pathway analysis showed many interested pathways which are upregulated after TGFb-1 treatment of hBMCs. Here, we show the top most upregulated pathways which include key osteoblast differentiation pathways.

Table S1: whole genome microarray mRNA data showing gene ENTITIES for TG1 versus CNT DOWN 1298 genes.

Table S2: whole genome microarray mRNA data showing gene ENTITIES for TG1 versus CNT UP 1932 genes.

Table S3: upregulated biological processes and related genes in TGFB1-treated cells using GO analysis.

Table S4: ultrastructural characteristics of CL1 cells under different treatment conditions.

Table S5: whole genome microarray mRNA data showing gene entities for CYD versus CNT up to 10,855 genes.

Table S6: whole genome microarray mRNA data showing gene entities for CYD versus CNT DOWN 2523 genes.

Table S7: real-time PCR human primer sequences used in this study.

Table S8: TAQMAN real-time PCR primers.