Abstract

The C1 cells are catecholaminergic and glutamatergic neurons located in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM). Collectively, these neurons innervate sympathetic and parasympathetic preganglionic neurons, the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus, and countless brain structures involved in autonomic regulation, arousal and stress. Optogenetic inhibition of rostral C1 neurons has little effect on BP at rest in conscious rats but produces large BP drops when the animals are anesthetized or exposed to hypoxia. Optogenetic C1 stimulation increases BP and produces arousal from non-REM sleep. C1 cell stimulation mimics the effect of restraint stress to attenuate kidney injury caused by renal ischemia-reperfusion. These effects are mediated by the sympathetic nervous system through the spleen and eliminated by silencing the C1 neurons. These few examples illustrate that, depending on the nature of the stress, the C1 cells mediate adaptive responses of a homeostatic or allostatic nature.

Keywords: Autonomic nervous system, anti-inflammatory reflex, cardiovascular homeostasis

Introduction

This review focuses on the contribution of the C1 cells to acute stress. We emphasize optogenetic experiments in awake rodents that illustrate the contribution of the C1 neurons to cardiovascular homeostasis and their lesser known role in allostasis (e.g. arousal, stress-induced glucose release and anti-inflammation).

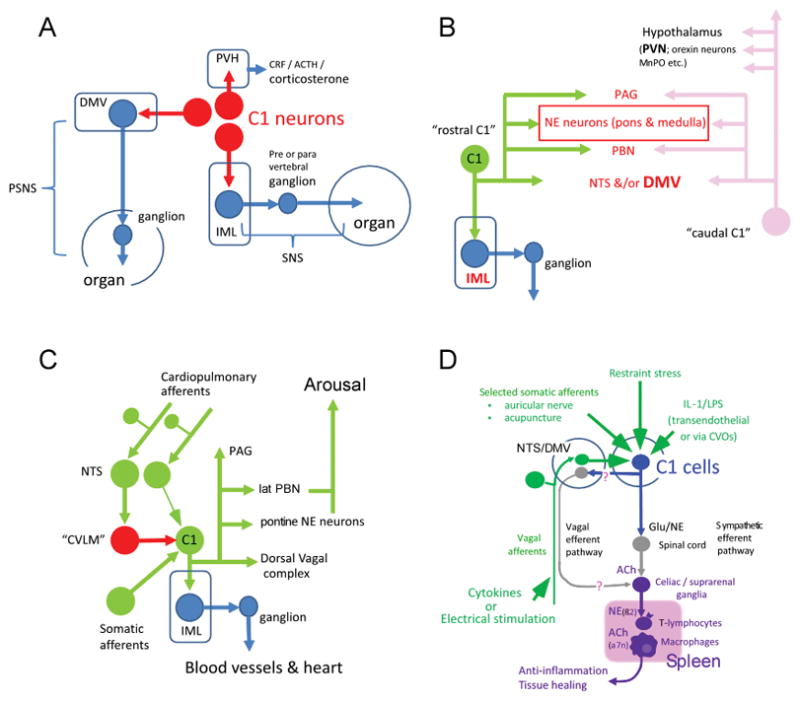

CNS “adrenergic” neurons express phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) by definition; the presence of PNMT and the absence of plasmalemmal catecholamine transporter distinguishes brainstem adrenergic neurons from their noradrenergic counterparts (for review: (Guyenet et al., 2013). C1, the largest cluster of adrenergic neurons, resides in the ventrolateral medulla oblongata (RVLM). There are at least three major subsets of C1 neurons (Figure, panels A,B). The bulbospinal C1 neurons are located at the rostral end of the RVLM (Tucker et al., 1987; Stornetta et al., 1999). As assumed since the 1980s, a large proportion of the bulbospinal C1 neurons regulate BP (see below). C1 cells without spinal projections innervate the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus and/or various thalamic, hypothalamic and basal forebrain targets (e.g. orexinergic neurons, medial preoptic region, amygdala (Abbott et al., 2013; Bochorishvili et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2017). The C1 cells that innervate the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV) may be a third major functional group. Most perhaps all, C1 neurons, including those that innervate the spinal cord, also innervate supraspinal nuclei (Haselton & Guyenet, 1990; Stornetta et al., 2016). Notably, bulbospinal and hypothalamus-projecting C1 cells innervate a common set of structures including the locus coeruleus, the dorsolateral pons and the periacqueductal gray matter (Figure, panel B) (Stornetta et al., 2016).

Figure.

A. C1 cells control both divisions of the autonomic nervous system via direct connections with preganglionic neurons. C1 cells also regulate the hypothalamo-pituitary axis (HPA) via direct connection to the paraventricular nucleus (PVH). The autonomic nervous system and the HPA can probably be affected by the C1 cells via more complex routes.

B. Bulbospinal C1 cells and C1 cells with hypothalamic projections have collaterals that target a common set of brain structures, notably the dorsal vagal complex (NTS &/or DMV), PBN, PAG and noradrenergic neurons including the locus coeruleus.

C. Schematic illustration of how the same C1 neurons might buffer BP changes and be responsible for hypertension and arousal. Rostral C1 neurons receive excitatory input from cardiopulmonary afferents such as those innervating the carotid bodies and inhibitory input from arterial and low-pressure baroreceptors. Activation of the latter inhibit C1 cells via a GABAergic relay located more caudally with the ventrolateral medulla (CVLM). Direct optogenetic stimulation of the C1 cells may cause arousal from sleep via the depicted C1 cell collaterals.

D. This diagram illustrates how C1 cell activation by such diverse stimuli as restraint stress, infection, acupuncture, vagal afferent stimulation (vagal trunk and auricular nerve) might be able to reduce inflammation. Two efferent routes converging on catecholaminergic neurons located within prevertebral ganglia are postulated, one via vagal efferent neurons (Pavlov & Tracey, 2015) and the other via sympathetic preganglionic neurons (Martelli et al., 2014a; Abe et al., 2017).

In short, the C1 cells regulate the pituitary adrenal axis and both divisions of the autonomic nervous system. Their effect on the parasympathetic and sympathetic outflows is exerted via direct excitatory inputs to preganglionic neurons and, presumably, via more complex routes involving innumerable structures implicated in autonomic regulations, arousal and stress.

C1 cells and BP regulation

The presence in the RVLM of bulbospinal neurons with a putative sympathoexcitatory function was suggested by several methods including single-unit recording (e.g. (Brown & Guyenet, 1985; Guyenet et al., 2013). Two sympathoexcitatory neuronal types, both glutamatergic, were later identified; 33–65% of them were deemed C1 cells because they contained a detectable level of tyrosine-hydroxylase or PNMT immunoreactivity (Lipski et al., 1995; Schreihofer & Guyenet, 1997).

Selective destruction of bulbospinal and other C1 cells produces minimal BP drops (<10 mmHg) but disrupts BP and glucose homeostasis (Madden et al., 2006). Thus, a relatively normal BP or glycemia is maintained without C1 cells in unanesthetized rodents but C1 cell activation is required for BP stability and glucose release during an acute cardiovascular stress (see also (Zhao et al., 2017)).

In anesthetized rats or in the working heart-brain preparation, selective inhibition of the C1 cells produces large decreases in sympathetic tone and BP (Marina et al., 2011; Wenker et al., 2017). In unanesthetized quietly awake rats, inhibition of the C1 cells causes very little hypotension at rest but, when the rats are subjected to hypoxia, C1 inhibition produces large drops in BP (Wenker et al., 2017). These results, like those of Madden et al. (2003; 2006), suggest that, in intact unanesthetized animals, the contribution of the C1 cells to BP is minimal at rest but that these cells are robustly activated to minimize the BP drop resulting from conditions that compromise the peripheral cardiovascular system, including hypoxia and general anesthesia.

C1 cells and arousal

In rats, optogenetic activation of the rostral C1 cells increases both BP and respiratory rate and causes arousal from non-REM sleep (Burke et al., 2014). Of note ~94% of the transduced neurons were demonstrably bulbospinal in these experiments. The lateral parabrachial nuclei, which have been implicated in CO2-induced arousal in mice (Kaur et al., 2013), the locus coeruleus and other noradrenergic neurons receive input from bulbospinal as well as hypothalamus-projecting C1 cells; these collateral projections likely contribute to the arousal elicited by C1 stimulation (Figure, panel C) (Holloway et al., 2013; Stornetta et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2017). By way of caveat, these gain-of-function experiments demonstrate that C1 cell activation has the potential to contribute to arousal from sleep. Further experiments (e.g. loss-of-function optogenetics) are needed to determine whether and under what circumstances C1 plays a role in arousal.

C1 cells, stress and hyperglycemia

Acute stress in the form of footshock, restraint, 2-deoxyglucose or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) increases plasma glucose and also activates C1 neurons (Pezzone et al., 1993; Ritter et al., 1998; Schiltz & Sawchenko, 2007; Zhao et al., 2017). In mice, stress-induced glucose release requires the integrity of the C1 cells and of the adrenal gland; it is suppressed when the C1 cells are selectively silenced and mimicked by their activation (Zhao et al., 2017). Most likely stress increases glucose release by activating those C1 cells that control the release of adrenaline from the adrenal medulla (Verberne et al., 2016).

Restraint stress, C1 cells and inflammation

Vagal nerve stimulation (VNS) reduces the production of inflammatory cytokines elicited by injection of LPS (Rosas-Ballina et al., 2011). This (anti-)inflammatory reflex operates largely via the noradrenergic innervation of the spleen and requires the activation of splenic macrophages by cholinergic T-cells (Pavlov & Tracey, 2015).

Sympathetic tone can exert anti-inflammatory effects. For example, in anesthetized animals, splanchnic nerve section enhances the production of TNFα elicited by LPS injection, implying that the production of this inflammatory cytokine is normally being restrained by ongoing sympathetic tone (Martelli et al., 2014b). Also, sympathetic hyperreflexia consecutive to high spinal cord lesions depresses the immune system (Ueno et al., 2016). The anti-inflammatory effect elicited by elevated sympathetic tone presumably enhances survival, along with increased vigilance, increased metabolic support (glucose and free fatty acid release), a rise in temperature and blood pressure, water conservation, etc. (Dhabhar, 2014). Accordingly, we tested whether acute behavioral stress might also activate the sympathetic system to reduce inflammation and organ damage and whether these effects might be mediated by C1 cell activation.

Renal ischemia-reperfusion (IR) carries a major risk of permanent injury to these organs; the damage is caused or at least exacerbated by inflammation (Inoue & Okusa, 2015). Ten minutes of restraint stress the day before substantially reduced renal damage elicited by IR (Abe et al., 2017). This protective effect was transferable to naïve mice by injecting splenocytes harvested from stressed mice and could also be induced by injection of CD4 splenic T cells harvested from control mice and incubated with noradrenaline in vitro (Abe et al., 2017). Protection against IR damage was also elicited by moderate (5Hz, 10 min) optogenetic activation of C1 cells in conscious mice. The protective effect of restraint stress was greatly attenuated in mice with selective C1 cell lesions or selective C1 inhibition during restraint (Abe et al., 2017). The protective effect of C1 stimulation disappeared after splenectomy or by silencing the autonomic nervous system with a ganglionic blocker during C1 stimulation. The protection could not be explained by corticosterone elevation because it was unchanged by administering mifepristone. Finally, the protection persisted after subdiaphragmatic vagotomy. Thus, restraint stress protects the kidneys from ischemic injury by activating the splenic anti-inflammatory mechanism originally described by Tracey and colleagues. However, in this instance the splenic noradrenergic innervation was activated, predominantly at least, via preganglionic sympathetic rather than parasympathetic neurons (Figure, panel D).

Conclusions

The C1 cells contribute to a variety of autonomic and neuroendocrine responses to acute stressors. They also likely regulate vigilance, attention and brain metabolism, probably by increasing CNS noradrenaline release. Depending on the circumstances, C1 cell activation can promote homeostasis (e.g. BP stabilization during hypoxia) or elicit adaptive but non homeostatic behavioral or autonomic responses (glucose release, arousal, anti-inflammation). Differentially regulated subgroups of C1 cells likely exist but their anatomical organization remains an enduring mystery. Global activation of the C1 neurons probably occurs, given that a very large percentage of these neurons express cFos after hypoxia, hypotension, glucoprivation, LPS injection etc. (e.g. (Parker et al., 2017)). The intensity of the stimulus is likely key. Severe acute stress including restraint or footshock may recruit C1 neurons en masse while subtler physiological perturbations (mild hemorrhage or hypotension, low dose LPS, moderate hypoglycemia) may engage more limited subsets of these neurons.

In the resting state, unlike under anesthesia or in reduced preparations, the contribution of the C1 neurons to BP seems minor (Wenker et al., 2017). This should not come as a surprise: microneurographic recordings in humans consistently show that, in a resting normovolemic conscious and minimally stressed mammal, the sympathetic vasoconstrictor tone required to maintain BP is extremely low. Robust sympathetic activation only occurs during stresses such as hypoxia, hypoglycemia, vasodilator administration, pain, etc., stimuli that are well-known to activate the C1 cells. Similarly, the (or a subset of) C1 cells appear to mediate stress-induced glucose release but, at rest, these cells have a negligible effect on blood glucose levels.

C1 neurons mediate or enable the activation of a splenic anti-inflammatory pathway by immobilization stress. In this instance, spleen activation occurs via a predominantly sympathetic route. All primary and secondary immune organs receive a noradrenergic innervation that originates from pre- or paravertebral ganglia. The existence of a sympathetic outflow that is specifically dedicated to the control of immune cells is as speculative as the existence of C1 cells dedicated to such outflow.

C1 neurons are quintessential reticular formation neurons that respond to a vast number of inputs. They could be a convergence point for multiple factors already known to elicit an anti-inflammatory reflex including vagus nerve afferent stimulation, somatic nerve stimulation (auricular nerve, acupuncture) or stress (Figure, panel D).

New findings.

In unanesthetized rats, C1 neurons contribute minimally to resting BP but their activation is required to maintain BP during hypoxia or general anesthesia. In addition to this anticipated homeostatic role, C1 neurons also mediate adaptive allostatic responses to stress including anti-inflammation and, possibly, arousal.

Acknowledgments

(Funding)

NHLBI grant HL028785 awarded to RLS and PGG

Abbreviations

- DMV

dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus

- IML

intermediolateral cell column

- IR

ischemia-reperfusion

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- PVH

paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus

- PSNS

parasympathetic nervous system

- SNS

sympathetic nervous system

Footnotes

Author contributions:

- conceived or designed the work; or

- acquired, analyzed, or interpreted data; AND

- drafted the work or revised it critically for important intellectual content.

- approved the final version of the manuscript and

- agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved;

All persons designated as authors qualify for authorship, and all those who qualify for authorship are listed.

Additional information:

Competing interests: the authors have no conflicts of interest.

Authors contribution: RLS and PGG co-wrote this review.

References

- Abbott SB, DePuy SD, Nguyen T, Coates MB, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Selective optogenetic activation of rostral ventrolateral medullary catecholaminergic neurons produces cardiorespiratory stimulation in conscious mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33:3164–3177. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1046-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abe C, Inoue T, Inglis MA, Viar KE, Huang L, Ye H, Rosin DL, Stornetta RL, Okusa MD, Guyenet PG. C1 neurons mediate a stress-induced anti-inflammatory reflex in mice. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:700–707. doi: 10.1038/nn.4526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bochorishvili G, Nguyen T, Coates MB, Viar KE, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. The orexinergic neurons receive synaptic input from C1 cells in rats. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:3834–3846. doi: 10.1002/cne.23643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DL, Guyenet PG. Electrophysiological study of cardiovascular neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla in rats. Circulation Research. 1985;56:359–369. doi: 10.1161/01.res.56.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke PG, Abbott SB, Coates MB, Viar KE, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Optogenetic stimulation of adrenergic C1 neurons causes sleep state-dependent cardiorespiratory stimulation and arousal with sighs in rats. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2014;190:1301–1310. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201407-1262OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhabhar FS. Effects of stress on immune function: the good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunologic Research. 2014;58:193–210. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8517-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet PG, Stornetta RL, Bochorishvili G, Depuy SD, Burke PG, Abbott SB. C1 neurons: the body’s EMTs. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;305:R187–204. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00054.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haselton JR, Guyenet PG. Ascending collaterals of medullary barosensitive neurons and C1 cells in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1990;258:R1051–R1063. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.258.4.R1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holloway BB, Stornetta RL, Bochorishvili G, Erisir A, Viar KE, Guyenet PG. Monosynaptic glutamatergic activation of locus coeruleus and other lower brainstem noradrenergic neurons by the c1 cells in mice. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:18792–18805. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2916-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue T, Okusa MD. Neuroimmune Control of Acute Kidney Injury and Inflammation. Nephron. 2015;131:97–101. doi: 10.1159/000438496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Pedersen NP, Yokota S, Hur EE, Fuller PM, Lazarus M, Chamberlin NL, Saper CB. Glutamatergic signaling from the parabrachial nucleus plays a critical role in hypercapnic arousal. Journal of Neuroscience. 2013;33:7627–7640. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0173-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipski J, Kanjhan R, Kruszewska B, Smith M. Barosensitive neurons in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of the rat in vivo: Morphological properties and relationship to C1 adrenergic neurons. Neuroscience. 1995;69:601–618. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)92652-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden CJ, Stocker SD, Sved AF. Attenuation of homeostatic responses to hypotension and glucoprivation after destruction of catecholaminergic rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) neurons. American Journal of Physiology: Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 2006;291:R751–R759. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00800.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden CJ, Sved AF. Cardiovascular regulation after destruction of the C1 cell group of the rostral ventrolateral medulla in rats. American Journal of Physiology: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2003;285:H2734–H2748. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00155.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marina N, Abdala AP, Korsak A, Simms AE, Allen AM, Paton JF, Gourine AV. Control of sympathetic vasomotor tone by catecholaminergic C1 neurones of the rostral ventrolateral medulla oblongata. Cardiovascular Research. 2011;91:703–710. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli D, McKinley MJ, McAllen RM. The cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway: A critical review. Auton Neurosci. 2014a;182:65–69. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli D, Yao ST, McKinley MJ, McAllen RM. Reflex control of inflammation by sympathetic nerves, not the vagus. Journal of Physiology. 2014b;592:1677–1686. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.268573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker LM, Le S, Wearne TA, Hardwick K, Kumar NN, Robinson KJ, McMullan S, Goodchild AK. Neurochemistry of neurons in the ventrolateral medulla activated by hypotension: Are the same neurons activated by glucoprivation? J Comp Neurol. 2017;525:2249–2264. doi: 10.1002/cne.24203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavlov VA, Tracey KJ. Neural circuitry and immunity. Immunol Res. 2015;63:38–57. doi: 10.1007/s12026-015-8718-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezzone MA, Lee WS, Hoffman GE, Pezzone KM, Rabin BS. Activation of brainstem catecholaminergic neurons by conditioned and unconditioned aversive stimuli as revealed by c-fos immunoreactivity. Brain Research. 1993;608:310–318. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(93)91472-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritter S, Llewellyn-Smith I, Dinh TT. Subgroups of hindbrain catecholamine neurons are selectively activated by 2-deoxy-D-glucose induced metabolic challenge. Brain Research. 1998;805:41–54. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00655-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosas-Ballina M, Olofsson PS, Ochani M, Valdes-Ferrer SI, Levine YA, Reardon C, Tusche MW, Pavlov VA, Andersson U, Chavan S, Mak TW, Tracey KJ. Acetylcholine-synthesizing T cells relay neural signals in a vagus nerve circuit. Science. 2011;334:98–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1209985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiltz JC, Sawchenko PE. Specificity and generality of the involvement of catecholaminergic afferents in hypothalamic responses to immune insults. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 2007;502:455–467. doi: 10.1002/cne.21329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreihofer AM, Guyenet PG. Identification of C1 presympathetic neurons in rat rostral ventrolateral medulla by juxtacellular labeling in vivo. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1997;387:524–536. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19971103)387:4<524::aid-cne4>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Akey PJ, Guyenet PG. Location and electrophysiological characterization of rostral medullary adrenergic neurons that contain neuropeptide Y mRNA in rat medulla. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1999;415:482–500. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19991227)415:4<482::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stornetta RL, Inglis MA, Viar KE, Guyenet PG. Afferent and efferent connections of C1 cells with spinal cord or hypothalamic projections in mice. Brain structure & function. 2016;221:4027–4044. doi: 10.1007/s00429-015-1143-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker DC, Saper CB, Ruggiero DA, Reis DJ. Organization of central adrenergic pathways: I. Relationships of ventrolateral medullary projections to the hypothalamus and spinal cord. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1987;259:591–603. doi: 10.1002/cne.902590408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno M, Ueno-Nakamura Y, Niehaus J, Popovich PG, Yoshida Y. Silencing spinal interneurons inhibits immune suppressive autonomic reflexes caused by spinal cord injury. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:784–787. doi: 10.1038/nn.4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verberne AJ, Korim WS, Sabetghadam A, Llewellyn-Smith IJ. Adrenaline: insights into its metabolic roles in hypoglycaemia and diabetes. Br J Pharmacol. 2016;173:1425–1437. doi: 10.1111/bph.13458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenker IC, Abe C, Viar KE, Stornetta DS, Stornetta RL, Guyenet PG. Blood Pressure Regulation by the Rostral Ventrolateral Medulla in Conscious Rats: Effects of Hypoxia, Hypercapnia, Baroreceptor Denervation, and Anesthesia. J Neurosci. 2017;37:4565–4583. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3922-16.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Wang L, Gao W, Hu F, Zhang J, Ren Y, Lin R, Feng Q, Cheng M, Ju D, Chi Q, Wang D, Song S, Luo M, Zhan C. A Central Catecholaminergic Circuit Controls Blood Glucose Levels during Stress. Neuron. 2017;95:138–152. e135. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]