Abstract

This article contains additional data related to the original research article entitled “KRIT1 loss-of-function induces a chronic Nrf2-mediated adaptive homeostasis that sensitizes cells to oxidative stress: implication for Cerebral Cavernous Malformation disease” (Antognelli et al., 2017) [1].

Data were obtained by si-RNA-mediated gene silencing, qRT-PCR, immunoblotting, and immunohistochemistry studies, and enzymatic activity and apoptosis assays. Overall, they support, complement and extend original findings demonstrating that KRIT1 loss-of-function induces a redox-sensitive and JNK-dependent sustained upregulation of the master Nrf2 antioxidant defense pathway and its downstream target Glyoxalase 1 (Glo1), and a drop in intracellular levels of AP-modified Hsp70 and Hsp27 proteins, leading to a chronic adaptive redox homeostasis that sensitizes cells to oxidative DNA damage and apoptosis.

In particular, immunoblotting analyses of Nrf2, Glo1, AP-modified Hsp70 and Hsp27 proteins, HO-1, phospho-c-Jun, phospho-ERK5, and KLF4 expression levels were performed both in KRIT1-knockout MEF cells and in KRIT1-silenced human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMEC) treated with the antioxidant Tiron, and compared with control cells. Moreover, immunohistochemistry analysis of Nrf2, Glo1, phospho-JNK, and KLF4 was performed on histological samples of human CCM lesions. Finally, the role of Glo1 in the downregulation of AP-modified Hsp70 and Hsp27 proteins, and the increase in apoptosis susceptibility associated with KRIT1 loss-of-function was addressed by si-RNA-mediated Glo1 gene silencing in KRIT1-knockout MEF cells.

Keywords: Cerebrovascular disease, Cerebral cavernous malformations, CCM1/KRIT1, Oxidative stress, Antioxidant defense, Adaptive redox homeostasis, Redox signaling, Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), c-Jun, Glyoxalase 1 (Glo1), Heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), Argpyrimidine-modified heat-shock proteins, Oxidative DNA damage and apoptosis

Specifications Table

| Subject area | Cellular and Molecular Biology |

| More specific subject area | Cell signaling |

| Type of data | Figures, images (IHC), histograms for quantitative data. |

| How data was acquired | Protein extraction and immunoblotting; nuclear extraction; qRT-PCR; immunohistochemistry (IHC); TUNEL assay. |

| Data format | Raw and analyzed. |

| Experimental factors | Cell transfection with siRNAs for KRIT1 and Glo1 gene expression knockdown |

| Cell treatments with the antioxidant Tiron. | |

| Experimental features | Measurement of cellular H2O2levels with the Amplex®Red Hydrogen Peroxide Assay. |

| Gene expression and enzyme activity assays, and Western blot analysis of total cell lysates and nuclear fractions in KRIT1-knockout MEF and KRIT1-silenced hBMEC cells. | |

| Immunohistochemistry studies on histological sections of paraffin-embedded, surgically resected human CCM specimens. | |

| Apoptotic cell death evaluated by TUNEL assay. | |

| Data source location | Department of Experimental Medicine, University of Perugia, Italy. |

| Department of Clinical and Biological Sciences, University of Torino, Italy. | |

| Data accessibility | The data is with the article. |

Value of the data

-

•

KRIT1 loss induces an adaptive redox homeostasis involving the Nrf2-Glo1 axis and AP-modified Hsps, which sensitizes cells to oxidative damage and apoptosis.

-

•

Major molecular phenotypes associated with KRIT1 loss-of-function, including the upregulation of ERK5 phosphorylation and KLF4 expression, are redox-dependent.

-

•

Cell treatment with the antioxidant Tiron rescues major molecular phenotypes associated with KRIT1 loss-of-function both in MEF and in hBMEC cells.

-

•

Endothelial cells lining human CCM lesions show increased levels of Glo1, phospho-JNK, and KLF4, as compared with normal vessels.

-

•

Presented data provide a novel mechanistic landscape for CCM disease pathogenesis, which has the potential to guide future development of targeted therapies.

1. Data

This dataset supports and extends the reproducibility of recent findings, demonstrating that the redox-sensitive upregulation of Glo1 and depletion of AP adducts, as well as the redox-sensitive nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 and upregulation of phospho-c-Jun and HO-1 detected in KRIT1-KO MEF occur also in KRIT1-silenced human brain endothelial cells (hBMEC). Moreover, it shows that Glo1 plays an important role in downregulation of AP-modified Hsp70 and Hsp27 proteins, and increased apoptosis susceptibility associated with KRIT1 loss-of-function. Furthermore, immunohistochemical analyses on histological samples of human CCM lesions demonstrate that, besides enhanced nuclear localization of Nrf2, endothelial cells lining human CCM lesions show also increased levels of Glo1 and phospho-JNK as compared with normal vessels, thus supporting and extending the results obtained in MEF and hBMEC cellular models.

In addition, this dataset shows also that other major molecular signatures of KRIT1 loss-of-function, including the upregulation of both ERK5 phosphorylation and KLF4 expression [2], [3], are redox-dependent and can be rescued by cell treatment with the mitochondria-permeable antioxidant Tiron, thereby connecting previously separate mechanisms on the unifying mechanistic landscape of abnormal adaptive responses to altered redox homeostasis and signaling consequent to KRIT1 dysfunction (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6).

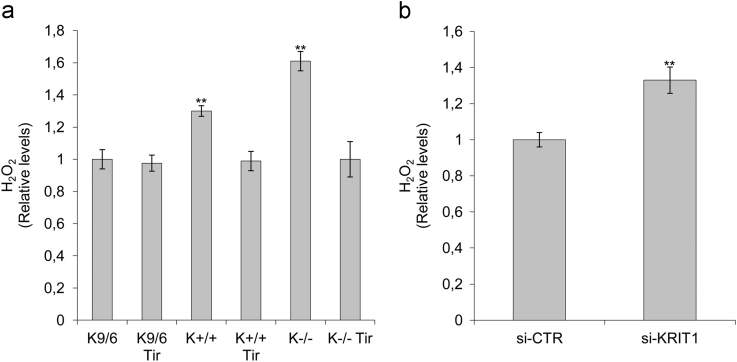

Fig. 1.

KRIT1 silencing results in increased H2O2 levels both in MEF and in hBMEC cells. a) H2O2 levels in wild type (K+/+), KRIT1−/− (K−/−), and KRIT1−/− re-expressing KRIT1 (K9/6) MEF cells left untreated or treated with the antioxidant Tiron (Tir; 5 mM for 24 h). b) H2O2 levels in human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMEC) transfected with either KRIT1-targeting siRNA (siKRIT1) or a scrambled control (siCTR). Cell extracts containing equal amounts of proteins were analyzed by the Amplex® Red Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase Assay Kit for assessment of H2O2 levels. Fluorescence intensities of the resorufin oxidation product, measured by a microplate reader 30 min after the initiation of the reaction, were expressed in arbitrary units and referred to as H2O2 levels relative to the average value of either K9/6 MEF or siCTR hBMEC control cells. Notice that KRIT1 silencing led to a significant increase in H2O2 levels both in MEF and in hBMEC cells.

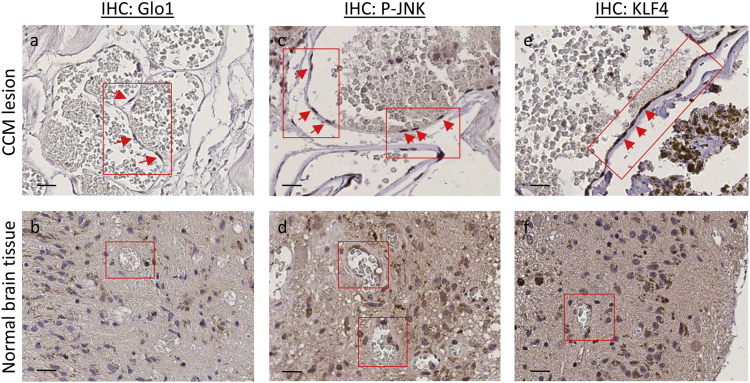

Fig. 2.

Upregulation of Glo1, phospho-JNK and KLF4 occurs in endothelial cells lining human CCM lesions. Histological sections of human CCM surgical specimens deriving from KRIT1 loss-of-function mutation carriers were analyzed by immunohistochemistry (IHC). Glo1 (a,b), phospho-JNK (c,d) and KLF4 (e,f) IHC staining of a representative CCM surgical sample containing large CCM lesions lined by a thin endothelium (a,c,e), and perilesional normal vessels serving as internal negative controls (b,d,f). Original magnification: ×400. Notice that a significant positive IHC staining is evident for both Glo1, phospho-JNK and KLF4 in endothelial cells lining the lumen of CCM lesions (panels a,c,e, respectively, red boxes and arrows), as compared with endothelial cells lining the lumen of perilesional normal vessels (panels b,d,f, respectively, red boxes). Scale bars: a,c,e, 30 µm; b,d,f, 200 µm.

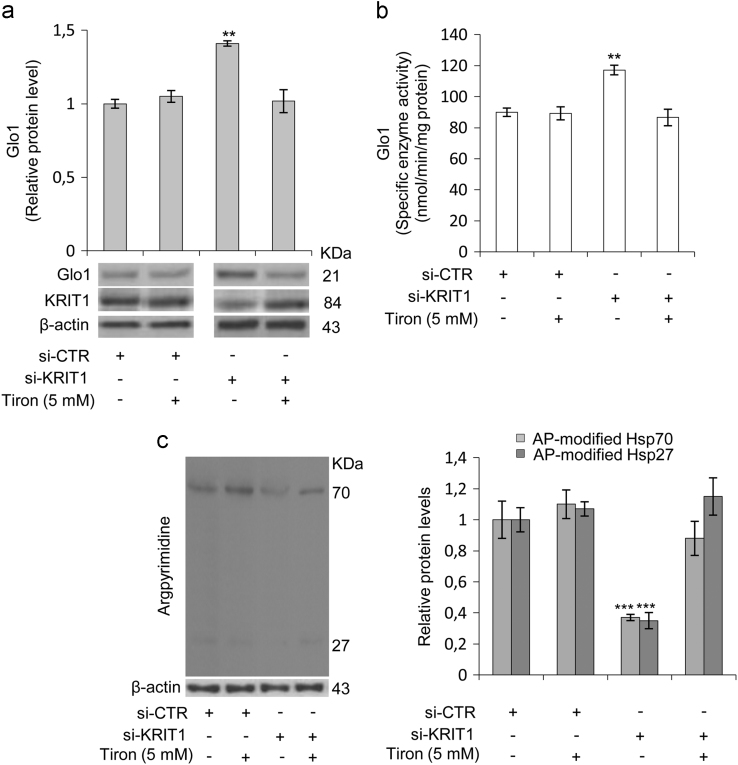

Fig. 3.

KRIT1 silencing in human brain microvascular endothelial cells causes a redox-dependent upregulation of Glyoxalase 1 (Glo1) and downregulation of argpyrimidine (AP) adducts. Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMEC) grown under standard conditions were transfected with either KRIT1-targeting siRNA (si-KRIT1) or a scrambled control (si-CTR). Cells were then either mock-treated or treated with the ROS scavenger Tiron (Tir, 5 mM for 24 h), lysed and analyzed by Western blotting (a,c) and spectrophotometric enzymatic assay (b). a) Representative WB and quantitative histogram of the relative KRIT1 and Glo1 protein expression levels in si-CTR and si-KRIT1 hBMEC cells either mock-treated (−) or treated (+) with Tiron. β-actin was used as internal loading control for WB normalization. The WB bands of Glo1 were quantified by densitometry, and normalized optical density values were expressed as relative protein level units referred to the average value obtained for mock-treated si-CTR samples. b) Glo1 enzyme activity was measured in cytosolic extracts of si-CTR and si-KRIT1 hBMEC cells, either mock-treated (−) or treated (+) with Tiron, according to a spectrophotometric method monitoring the increase in absorbance at 240 nm due to the formation of S-D- lactoylglutathione. Glo1 activity is expressed in milliunits per mg of protein, where one milliunit is the amount of enzyme that catalyzes the formation of 1 nmol of S-D-lactoylglutathione per min under assay conditions. Results represent the mean (± SD) of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. c) Representative WB and quantitative histogram of argpyrimidine (AP) adducts in si-CTR and si-KRIT1 hBMEC cells, either mock-treated (−) or treated (+) with Tiron, as detected using a specific mAb. β-actin was used as internal loading control for WB normalization. Notice treatment of si-KRIT1 hBMEC cells with the antioxidant Tiron rescued the significant increase in Glo1 expression and activity, and decrease in both 70 and 27 kDa AP adducts caused by KRIT1 knockdown.

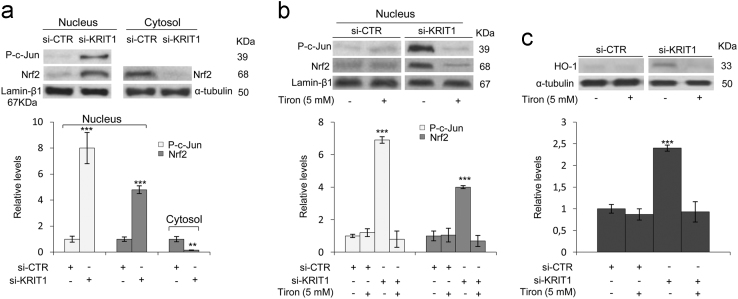

Fig. 4.

KRIT1 silencing in human brain microvascular endothelial cells causes a redox-dependent activation of the Nrf2 antioxidant response pathway. Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMEC) grown under standard conditions were transfected with a KRIT1-targeting siRNA (si-KRIT1) or a scrambled control (si-CTR), and then either mock-treated or treated with the ROS scavenger Tiron (Tir, 5 mM for 24 h). Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions (a,b) or total cell extracts (c) were then obtained and analyzed by Western blotting for Nrf2 (a,b) and HO-1 (c). Nuclear levels of p-c-Jun were used as a control of redox-dependent effect of KRIT1 loss-of-function [4]. Lamin-β1 and α-tubulin were used as internal loading controls for WB normalization of nuclear and total/cytoplasmic proteins, respectively. (a,b,c) The histograms below their respective Western blots represent the mean (± SD) of the densitometric quantification of three independent experiments. Notice that the upregulation of p-c-Jun nuclear levels induced by KRIT1 loss-of-function is paralleled by a marked nuclear accumulation of Nrf2 (a,b) and the upregulation of its downstream effector HO-1 (c), both of which are significantly reverted by cell treatment with the ROS scavenger Tiron (b,c).

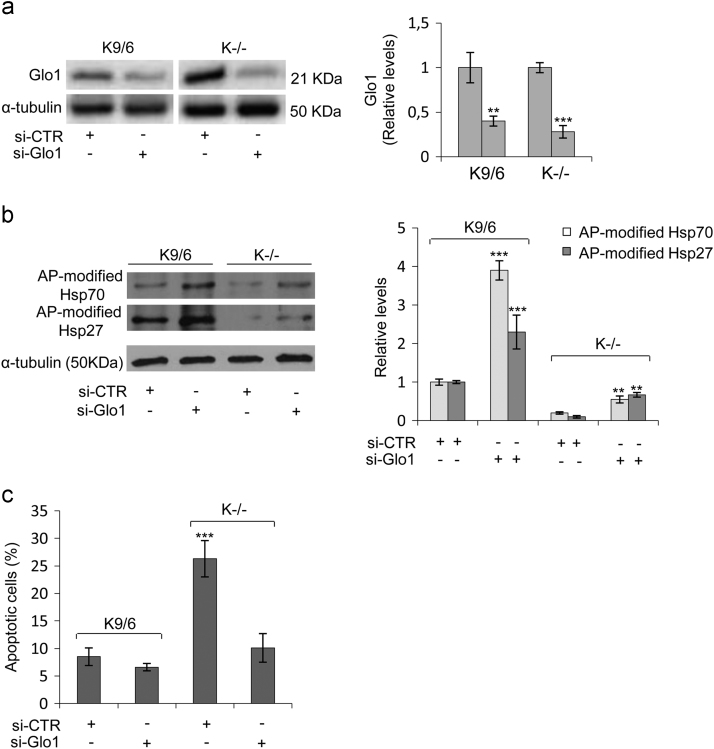

Fig. 5.

The downregulation of AP-modified Hsps and increased apoptosis susceptibility caused by KRIT1 loss-of-function are linked to the upregulation of Glo1. KRIT1−/− (K−/−) and KRIT1−/− re-expressing KRIT1 (K9/6) MEF cells grown to confluence under standard conditions were transiently transfected with either a pool of four siRNAs targeting Glo1 (si-Glo1) or non-targeting siRNAs used as negative control (si-CTR), and Glo1 (a), AP-modified Hsp70 and Hsp27 (b), and apoptosis (c) levels were assayed as described in Section 2. (a,b) Representative Western blots and quantitative histograms of the relative expression levels of Glo1 (a) and argpyrimidine (AP) adducts (b) in K9/6 and K−/− MEF transfected with si-CTR or si-Glo1, as detected using specific antibodies. α-tubulin was used as internal loading control for WB normalization. WB bands were quantified by densitometry, and normalized optical density values were expressed as relative protein level units. The histograms beside their representative Western blots show the mean (± SD) of the densitometric quantification of three independent experiments. (c) Apoptotic cell death evaluated by TUNEL assay in K9/6 and K−/− MEF transfected with si-CTR or si-Glo1. Histograms represent the mean (± SD) of 3 independent experiments performed in triplicate. Notice that Glo1 silencing induced a significant rescue of both the downregulation of AP-modified Hsp70 and Hsp27 levels, and the increased apoptosis susceptibility associated with KRIT1 loss-of-function.

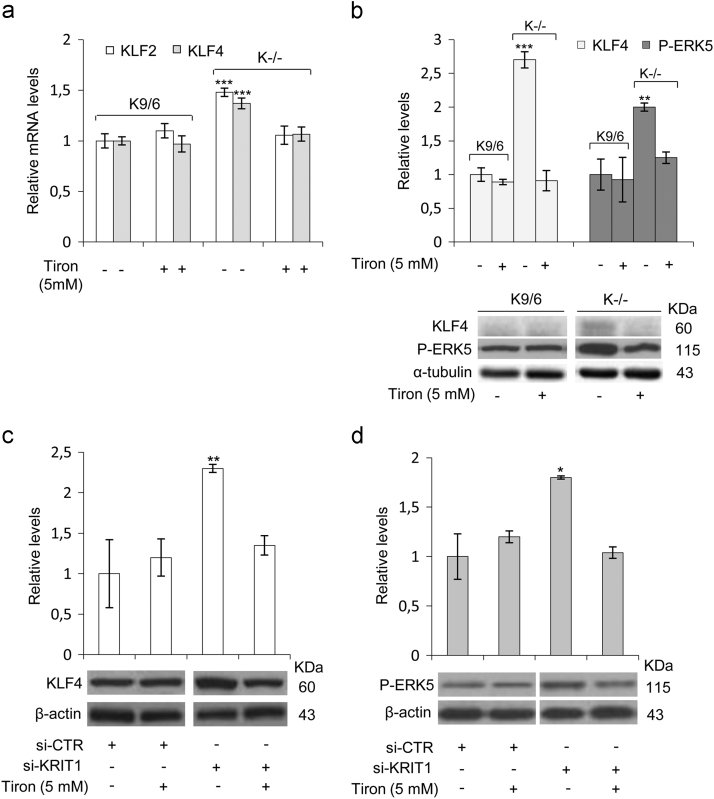

Fig. 6.

The upregulation of ERK5 phosphorylation and KLF2/4 expression caused by KRIT1 loss-of-function are redox-dependent events. KRIT1−/− (K−/−) and KRIT1−/− re-expressing KRIT1 (K9/6) MEF cells (a,b), and human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMEC) transfected with KRIT1-targeting siRNA (si-KRIT1) or a scrambled control (si-CTR) (c,d), were mock-treated (−) or treated (+) with the ROS scavenger Tiron (Tir, 5 mM for 24 h), lysed and analyzed by either qRT-PCR (a) or Western blotting (b,c,d). (a) KLF2 and KLF4 mRNA expression levels in K−/− and K9/6 MEF cells untreated (-) or treated (+) with the ROS scavenger Tiron were analyzed in triplicate by qRT-PCR, and normalized to the amount of an internal control transcript (GAPDH). Results are expressed as relative mRNA level units referred to the average value obtained for control cells (untreated K9/6 MEF), and represent the mean (± SD) of 3 independent qRT-PCR experiments. (b,c,d) KLF4 and phospho-ERK5 (P-ERK5) protein levels were analyzed by Western blotting with specific affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies both in K−/− and K9/6 MEF cells (b), and in si-KRIT1 and si-CTR hBMEC (c,d) untreated (−) or treated (+) with the ROS scavenger Tiron. α-tubulin and ß-actin were used as internal loading controls for WB normalization of total proteins. WB bands were quantified by densitometry, and normalized optical density values were expressed as relative protein level units. The histograms above representative Western blots show the mean (± SD) of the densitometric quantification of three independent experiments. Notice that upregulation of both ERK5 phosphorylation and KLF4 expression caused by KRIT1 loss-of-function were rescued by cell treatment with the antioxidant Tiron.

2. Experimental design, materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture and treatment

Wild type (K+/+), KRIT1−/− (K−/−), and KRIT1−/− re-expressing KRIT1 (K9/6) MEF cells, and human brain microvascular endothelial cells (hBMEC) transfected with either KRIT1-targeting siRNA (siKRIT1) or a scrambled control (siCTR) were obtained, cultured and treated as described in [1].

Briefly, cell treatments were performed with the mitochondria-permeable antioxidant Tiron (4,5-dihydroxy-1,3-benzenedisulfonic acid disodium salt monohydrate, Sigma-Aldrich) (5 mM for 24 h), the JNK inhibitor SP600125 (Calbiochem) (25 µM for 1 h) [4], and the autophagy inducer Rapamycin (Calbiochem) (500 nM for 4 h) [5].

2.2. Cell transfection and siRNA-mediated gene silencing

Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated knockdown of KRIT1 was performed as described in [1].

For siRNA-mediated knockdown of Glo1, K−/− and K9/6 MEF cells were transiently transfected with either a pool of four siRNAs targeting Glo1 (si-Glo1) (ON-TARGET plus SMART pool mouse Glo1 siRNA, L-063339-00-0005, Dharmacon) or non-targeting siRNAs used as negative control (si-CTR) (ON-TARGET plus Non-targeting Control pool, D-001810-10-05, Dharmacon), as previously described [6]. Upon transfection, cells were seeded into assay plates and subjected to experimental conditions within 48–72 h. The knockdown efficiency was monitored by quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and Western blot (WB) analysis.

2.3. Quantitative real time PCR analysis (qRT-PCR)

RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and quantitative real time PCR analysis (qRT PCR) were performed as described in [1]. In particular, the expression levels of KLF2 and KLF4 transcripts in MEF cells were quantified using specific Sybr Green qRT-PCR assays based on the following published oligonucleotide primer sequences: Mus musculus KLF2: 5′-cgcctcgggttcatttc-3′ (forward, 600 nM), 5′-agcctatcttgccgtccttt-3′ (reverse, 600 nM); Mus musculus KLF4: 5′-gtgccccgactaaccgttg-3′ (forward, 600 nM), 5′-gtcgttgaactcctcggtct-3′ (reverse, 600 nM) [2].

2.4. Protein extraction and Western blotting

Protein extraction and Western blotting were performed as described in [1].

Specifically, primary antibodies used in Western blotting experiments were the following: rat anti-Glyoxalase 1 mAb (6F10) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); mouse anti-Methylglyoxal-AGE (Arg-Pyrimidine) mAb (clone 6B) (BioLogo, Hamburg, Germany); rabbit anti-Nrf2 pAb (Bioss Antibodies, Sial, Rome, Italy); rabbit anti-Nrf2 mAb [EP1808Y] (AB62352, Abcam); mouse anti-Heme Oxygenase 1 mAb [HO-1-1] (Abcam); rabbit anti-c-Jun pAb (H-79) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); mouse anti-phospho-c-Jun mAb (KM-1) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); rabbit anti phospho-Erk5 (Thr218/Tyr220) pAb (3371, Cell Signaling Technology); goat anti-mouse KLF4 pAb (AF3158, R&D Systems); goat anti-human KLF4 pAb (AF3640, R&D Systems); mouse anti-α-tubulin mAb (Sigma-Aldrich); mouse anti-β-actin mAb (C4) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology); rabbit anti-lamin β1 pAb (H-90) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Protein bands from western blots were quantified by densitometry using the ImageJ software, and their relative amounts were normalized to the levels of housekeeping proteins serving as internal loading controls.

2.5. Immunohistochemical analysis

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses were performed on histological samples of human CCM lesions obtained from paraffin-embedded surgically resected CCM specimens, retrieved from the Department of Anatomy and Diagnostic Histopathology at the University Hospital “Città della Salute e della Scienza” of Turin, using a Ventana Autostainer Benchmark Ultra (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc.) as described in [1].

Briefly, histological sections (2 μm thick) of selected paraffin-embedded CCM specimens were incubated for 32 min at 37 °C with appropriate dilutions of primary antibodies, including rat anti-Glyoxalase 1 mAb (6F10) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), mouse anti-p-JNK mAb (G-7) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and goat anti-human KLF4 (AF3640; R&D Systems) affinity-purified polyclonal antibodies, followed by incubation with Discovery Universal Secondary Antibody Ventana (Roche). ICH labeling was then developed by a 5- to 10-min incubation with 3,3′ diaminobenzidine (DAB) + H2O2 substrate chromogen. The sections were subsequently counterstained with hematoxylin, and digitized at 40× magnification using a Hamamatsu's High-Resolution Nanozoomer S210 whole slide scanner (Hamamatsu Photonics).

2.6. Enzymatic activity assays

Glo1 activity in cell extracts was assayed as described in [1].

2.7. Measurement of cellular H2O2 levels

In addition to the methods for detecting intracellular levels of general and specific ROS described in [1] and reported previously [4], [5], [7], complementary measurements of cellular H2O2 levels were performed with the Amplex® Red Hydrogen Peroxide/Peroxidase Assay Kit (A22188, Invitrogen, Milan, Italy), according to the manufacturer's instructions with some modifications [8]. This assay is based on the Amplex® Red reagent (10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine), a selective and highly sensitive fluorogenic probe that reacts with H2O2 at a stoichiometry of 1:1 in a reaction catalyzed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP) to generate the red-fluorescent oxidation product resorufin (7-hydroxy-3H-phenoxazin-3-one) [9], and has been instrumental to gaining insights into the mechanism of mitochondrial ROS production [8].

Briefly, cells grown to confluence in complete medium were lysed in 250 μl of RIPA buffer containing phenylmethyl sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (100 µM; Sigma), and cell extract supernatants containing an equal amount of proteins (35 μg) in a final volume of 50 μl were then used to run the H2O2 assay in 96-well microplates protected from light, according to manufacturer's instructions. Specifically, reactions containing 50 μl of cell extract, 100 µM Amplex® Red reagent and 0.2 U/ml HRP in 1x reaction buffer (50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4), were incubated for 30 min at room temperature, and fluorescence intensity of the oxidation product, resorufin, was then measured with a microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc., USA) using excitation at 530 nm and fluorescence detection at 595 nm. Background fluorescence, determined for a no-HRP control reaction, was subtracted from each value.

2.8. Apoptosis detection

Apoptosis was detected by evaluating DNA fragmentation by TdT-mediated dUTP nick-end labeling (TUNEL) assay (ApoAlert® DNA Fragmentation Assay, Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) [10].

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to gratefully acknowledge Luca Goitre, Roberta Frosini, Francesca Veneziano, Irene Schiavo, Valerio Benedetti, Sara Sarri, Federica Quesada, Giulia Costantino, Federica Geddo, Alessia Zotta, and Diego Catanese for providing help in some experiments. Moreover, they acknowledge the Italian Research Network for Cerebral Cavernous Malformation (CCM Italia, http://www.ccmitalia.unito.it), the Associazione Italiana Angiomi Cavernosi (AIAC, http://www.ccmitalia.unito.it/aiac), and Santina Barbaro for fundamental collaboration and support, and helpful discussion.

This work was supported by the Telethon Foundation (Grant GGP15219 to SFR).

Footnotes

Transparency document associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.dib.2017.12.026.

Transparency document. Supplementary material

Transparency document

.

References

- 1.Antognelli C., Trapani E., Monache S.D., Perrelli A., Daga M., Pizzimenti S., Barrera G., Cassoni P., Angelucci A., Trabalzini L., Talesa V.N., Goitre L., Retta S.F. KRIT1 loss-of-function induces a chronic Nrf2-mediated adaptive homeostasis that sensitizes cells to oxidative stress: implication for Cerebral Cavernous Malformation disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Z., Tang A.T., Wong W.Y., Bamezai S., Goddard L.M., Shenkar R., Zhou S., Yang J., Wright A.C., Foley M., Arthur J.S., Whitehead K.J., Awad I.A., Li D.Y., Zheng X., Kahn M.L. Cerebral cavernous malformations arise from endothelial gain of MEKK3-KLF2/4 signalling. Nature. 2016;532:122–126. doi: 10.1038/nature17178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cuttano R., Rudini N., Bravi L., Corada M., Giampietro C., Papa E., Morini M.F., Maddaluno L., Baeyens N., Adams R.H., Jain M.K., Owens G.K., Schwartz M., Lampugnani M.G., Dejana E. KLF4 is a key determinant in the development and progression of cerebral cavernous malformations. EMBO Mol. Med. 2016;8:6–24. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goitre L., De Luca E., Braggion S., Trapani E., Guglielmotto M., Biasi F., Forni M., Moglia A., Trabalzini L., Retta S.F. KRIT1 loss of function causes a ROS-dependent upregulation of c-Jun. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2014;68:134–147. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marchi S., Corricelli M., Trapani E., Bravi L., Pittaro A., Delle Monache S., Ferroni L., Patergnani S., Missiroli S., Goitre L., Trabalzini L., Rimessi A., Giorgi C., Zavan B., Cassoni P., Dejana E., Retta S.F., Pinton P. Defective autophagy is a key feature of cerebral cavernous malformations. EMBO Mol. Med. 2015;7:1403–1417. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talesa V.N., Ferri I., Bellezza G., Love H.D., Sidoni A., Antognelli C. Glyoxalase 2 is involved in human prostate cancer progression as part of a mechanism driven by PTEN/PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling with involvement of PKM2 and ERalpha. Prostate. 2017;77:196–210. doi: 10.1002/pros.23261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goitre L., Balzac F., Degani S., Degan P., Marchi S., Pinton P., Retta S.F. KRIT1 regulates the homeostasis of intracellular reactive oxygen species. PLoS One. 2010;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miwa S., Treumann A., Bell A., Vistoli G., Nelson G., Hay S., von Zglinicki T. Carboxylesterase converts Amplex red to resorufin: implications for mitochondrial H2O2 release assays. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2016;90:173–183. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhee S.G., Chang T.S., Jeong W., Kang D. Methods for detection and measurement of hydrogen peroxide inside and outside of cells. Mol. Cells. 2010;29:539–549. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Antognelli C., Palumbo I., Aristei C., Talesa V.N. Glyoxalase I inhibition induces apoptosis in irradiated MCF-7 cells via a novel mechanism involving Hsp27, p53 and NF-kappaB. Br. J. Cancer. 2014;111:395–406. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document