Abstract

Infancy is the most critical period in human brain development. Studies demonstrate that subtle brain abnormalities during this state of life may greatly affect the developmental processes of the newborn infants. One of the rapidly developing methods for early characterization of abnormal brain development is functional connectivity of the brain at rest. While the majority of resting-state studies have been conducted using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), there is clear evidence that resting-state functional connectivity (rs-FC) can also be evaluated using other imaging modalities. The aim of this review is to compare the advantages and limitations of different modalities used for the mapping of infants’ brain functional connectivity at rest. In addition, we introduce photoacoustic tomography, a novel functional neuroimaging modality, as a complementary modality for functional mapping of infants’ brain.

Keywords: Neonatal brain, Infants, Neuroimaging modalities, Resting-state functional connectivity, Photoacoustic tomography

1. Introduction

Because studies of human infants are not amenable to invasive manipulations, advanced non-invasive modalities and analytical approaches, such as brain functional connectivity (FC), have been adapted from the adult literature to analyze neonatal brain functional data. FC is a statistical association of neuronal activity time courses across distinct brain regions, supporting specific cognitive processes [1]. Advances in imaging modalities have improved our understanding of how functional brain connectivity develops during the neonatal period [[2], [3], [4]] and how various brain injuries may affect the development of the immature brain [5].

When these associations are examined in the absence of any external tasks, they demonstrate whether and how different brain areas are synchronized to form resting-state networks (RSNs) [6]. These RSNs, also called intrinsic networks [7,8], are spatially distinct regions of the brain that exhibit a low-frequency temporal coherence and provide a means to depict the brain’s functional organization. RSNs have been reasonably well-characterized in healthy adults [9].

Initial description of immature forms of RSNs was reported by Fransson, et al. [10], who found five distinct RSNs in a cohort of very preterm (born ≤ 30 weeks gestation) infants at term equivalent postmenstrual age. More recent works have also examined large-scale RSNs architecture supporting motor, sensory, and cognitive functions in term- [3,4] and preterm-born infants [[11], [12], [13], [14]] as well as in the pediatric age group [15,16]. These studies have identified some RSNs grossly similar to those of adults. Moreover, at least two studies have observed RSN activity in human fetuses in utero [17,18]. The application of resting-state functional connectivity (rs-FC) has provided novel insight into the neurobiological basis of developmental abnormalities, with recent literature implicating network specific disruptions in RSN architecture in pediatric disorders such as autism spectrum disorders [19], attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [20], and Tourette syndrome [21].

Different neuroimaging modalities have been employed to study the human infant brain at rest, providing complementary information about the brain’s structure and function [22]. Converging results obtained across different modalities and analysis protocols adds to the robustness of the knowledge gained. The emergence and advancement of functional modalities and analysis techniques have allowed studies of early functional cerebral development. Major neuroimaging modalities include: functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) [23], electroencephalography (EEG) [24,25], magnetoencephalography (MEG) [27], positron emission tomography (PET) [27], functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) [28], diffuse optical tomography (DOT) [29], and functional ultrasound (fUS) imaging.

Although all of the above modalities study regional brain activity, they are based on different detection methods, they have different spatial and temporal resolutions and different noise characteristics, especially when they are used to studying infants. While each modality delivers novel insights into the earliest patterns of cerebral connectivity, they raise new questions regarding the role of RSNs and their value as a neuroimaging biomarker or diagnostic tool at the individual level. Therefore, the focus of the current review is on the rs-FC studies using different modalities in the early stages of human brain development. We discuss various methodological challenges posed by these promising modalities. We also highlight that, despite these challenges, early work indicates a strong correlation among these modalities in the study of RSNs. Finally, we focus on photoacoustic tomography (PAT) [[30], [31], [32]], an emerging imaging modality, illustrating its strengths and limitations, and discussing its potential role in the field of resting-state functional brain connectivity studies in infants.

2. Resting-state functional connectivity analysis

The theory of connectivity among different regions of the brain is one of the oldest notions in neuroscience ([33] and references therein). Beside anatomical connectivity, two other forms of brain connectivity are defined: functional and effective connectivity, two concepts derived from functional neuroimaging modalities. While the effective connectivity (EF) describes causal interactions between activated brain areas, FC refers to statistical dependency among activity of distinct and distant neural populations. The underlying assumption is that low-frequency temporal correlations among different brain regions represent FC patterns. In the absence of external stimuli, these connectivity patterns have been termed ‘intrinsic connectivity networks’ [34] or ‘resting-state networks’, RSNs [35].

Most of the work done in examining patterns of rs-FC strongly support the hypothesis that patterns of rs-FC (aka RSNs) represent highly organized and spatially coordinated signaling activity within known brain systems that are critical for basic brain functions [36]. Some groups have shown that the magnitude of rs-FC can be used to infer the cerebral metabolic rate of glucose [37], while others have shown that brain regions exhibiting a high number of functional connections exhibit high aerobic glycolysis [38,39]. RSNs can be reliably and reproducibly detected at the individual subject and group levels across a range of analysis techniques [40,41].

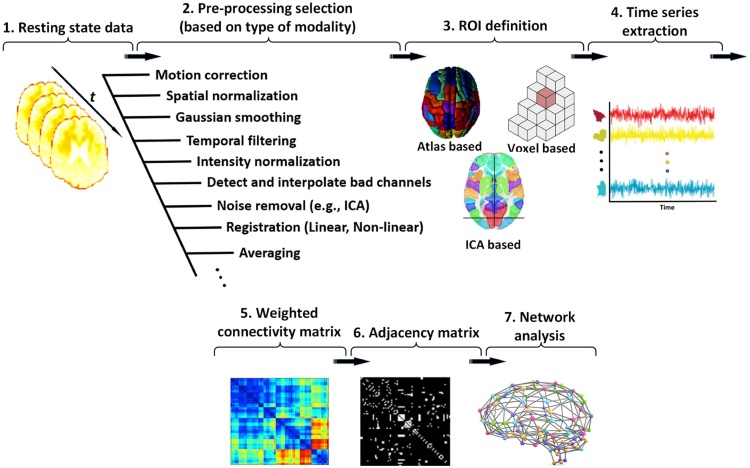

Fig. 1 demonstrates the basic pipeline which could be used in most FC studies for different imaging modalities. Following image pre-processing (e.g. motion correction, spatial normalization, smoothing), a number of methods can be used to extract the FC patterns from the data, each with its own inherent advantages and disadvantages. These approaches examine the existence and extent of FC between brain regions, and include seed-based methods [6,42,43], independent component analysis (ICA) [44,45], clustering [46,47], and graph theory [48].

Fig. 1.

Overview of the pipeline for rs-FC data analysis. The processing steps are (1) data acquisition, (2) pre-processing, (3) region of interest (ROI) definition, (4) time-series extraction [49], (5) correlation analysis to generate weighted FC matrix, (6) thresholding to generate an adjacency matrix [50], and (7) network analysis.

2.1. Seed-based analysis

Traditionally, the FC among the brain regions is assessed using pre-specified regions of interest (ROIs) (i.e., “seed regions”) from which the time-varying resting state signals are extracted in order to compute their correlation with signals in other brain areas [6]. To this end, the average time courses of all voxels within a seed (ROI) is found and the connectivity maps are calculated by computing the correlation between the mean time course and all voxel time courses within a brain mask (Fig. 2, 1st panel). Correlations are calculated using metrics, such as the Pearson correlation coefficients. After constructing FC maps from the individual subjects’ data collected at rest and calculating group-level statistics, inferential tests are applied to examine the existence of functional connections between different areas. Also, the contents of FC maps are used as features and then they are used to train a supervised machine learning algorithm for classification. Finally, the results, implications, and potential issues are explored and the significant features can be used to find new biomarkers for brain disease diagnosis. The seed-based approach was the first method adopted by Biswal et al. to identify the resting state networks [6] and is the most straight forward method for rs-FC data analysis. It is a model-based, robust and conceptually clear method, though, it relies strongly on some prior knowledge for the identification of the seed regions. Thus, it does not determine the nature and number of independent networks supporting the resting-state of the brain function.

Fig. 2.

Schematic of different resting state functional connectivity approaches including (1 st panel) In seed-based analysis, based on the time series of a seed voxel (or ROI), connectivity is calculated as the correlation of time series for all other voxels in the brain. The result of this analysis is a connectivity map showing Z-scores for each voxel (seed) indicating how well its time series correlates with the time series of other seeds. (2nd panel) In ICA, the functional data for different time points are reshaped to a single matrix (X). Then, based on the maximization of independence, this matrix is decomposed into two matrices: mixing matrix A, and source matrix S [54,55]. (3rd panel) In the graph theory the pipeline are as follow: (1) Extraction of the time-course of resting state data within each anatomical unit (ROI); (2) Calculation of a FC (i.e., network edge) correlation matrix between any pairs of nodes; (3) Thresholding the correlation matrix into a binary adjacency matrix; (4) Calculation of different graph theory metrics [56,57]. (4th panel) In clustering, after generating the initial connectivity map, based on a set of relevant characteristics, clustering algorithms attempt to group samples that are alike [58,59].

2.2. Independent component analysis

Another popular approach for extracting FC patterns is based on ICA, a mathematical technique that maximizes statistical independence among extracted components (Fig. 2, 2nd panel). As a data-driven approach, the primary advantage of ICA is its freedom from hypotheses preceding the analysis and voiding the need for selection of seed regions [44] but it forces the user to manually select the important components and distinguish noise from physiologic signals. ICA facilitates the effective extraction of distinct RSNs by decomposing the fMRI time series of the whole brain voxels to spatially and temporally independent components. It describes the temporal and spatial characteristics of the underlying hidden components or networks [7,51].

Apart from the seed-based analysis, which finds the interaction between the seed region and the entire brain, ICA investigates multiple simultaneous voxel to voxel interactions of distinct networks in the brain. Despite such differences, Rosazza et al. [52] demonstrated that the results of seed-based analysis and ICA were similar in a group of healthy subjects. A comprehensive review of the above and related methods was published by Li, et al. [53].

2.3. Graph theory

Graph methods provide a distinct alternative to seed-based and ICA methods [48,[60], [61], [62], [63]]. This approach views RSNs as a collection of nodes connected by edges (Fig. 2, 3rd panel). Here, the relation between the nodes and edges can be established as where V is a gathering of nodes connected by edges E, which describes the interaction between nodes. In this approach, ROIs are represented by nodes and the correlations among the ROIs are demonstrated as the level of connectivity (weights) using the edges. The characteristics of the graph can be evaluated to quantify the distribution of functional hubs (highly functionally connected nodes) in the human brain [38,63]. Examples of measures of interest include: (i) average path length; (ii) clustering coefficient; (iii) nodal degree; (iv) centrality measures; and (v) level of modularity [63]. Using the graph theory technique, several studies have demonstrated that the brain exhibits a small world topology. Small world topology was first described in social networks. It allows each node to have a relatively low number of connections while still being connected to all other nodes within a short distance (that is, short distances between any two nodes). The small world is achieved through the existence of hubs, which are critical nodes with large number of connections, allowing a high level of local connectivity (neighboring nodes) [48]. While seed-based analysis focuses only on the strength of correlation between one ROI to another, graph theory measures the topological properties of an ROI within the whole brain or the network related to a particular function. It has exhibited good correspondence with well-known anatomical white matter tracts (structural highways of the brain) and resting-state networks [64].

2.4. Clustering

Another method used to analyze resting-state data is clustering. Clustering algorithms attempt to group samples that are alike, based on a set of relevant characteristics in such a way that samples in a cluster are more similar to each other than those in other clusters (Fig. 2, 4th panel). Similarity may be measured by metrics such as Pearson correlation coefficient. An example of a clustering algorithm is the hierarchical clustering [46,62], which builds a dendrogram of all samples. Other examples are K-means [65], c-means [66], spectral-based [67], and graph-based [47] clustering algorithms.

3. Neuroimaging modalities for measuring resting-state functional connectivity

3.1. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)

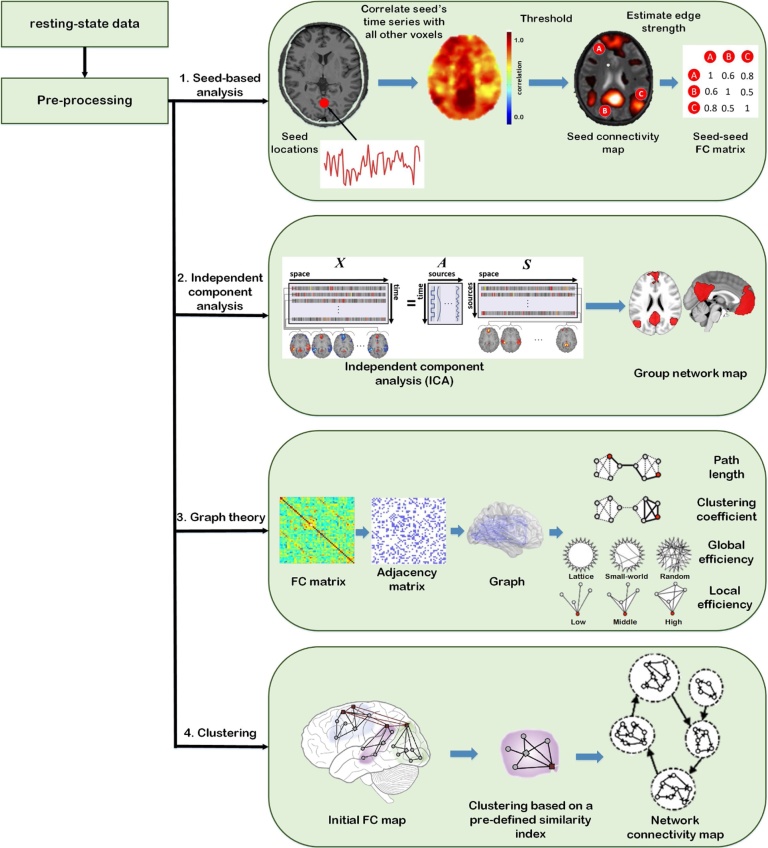

FMRI is a non-invasive imaging modality that measures the brain activity using blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) contrast [68,69]. The BOLD contrast detected by fMRI at rest is spontaneous, spatially-coherent, and characterized by low-frequency (<0.1 Hz) fluctuations of neuronal activity [6]. The mechanism of formation of an MR image based on the BOLD signal is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Formation of MRI based on the BOLD signal has several constituents: (1) a stimulus or modulation in background activity; (2) neuronal response; (3) synaptic or metabolic signaling; (4) complex relationship between neuronal activity and triggering a hemodynamic response (termed neurovascular coupling); (5) hemodynamic response itself [76]; and (6) the way in which this response is detected by an MRI scanner [77].

While our understanding of the resting-state network remains incomplete, it is widely used for the identification of FC and accurate mapping of large-scale functional networks across the brain [6,16]. Several studies used rs-fMRI to characterize the functional organization of the healthy neonatal brain. It has been shown that many of the functional brain networks in adults are also present in newborn infants [70] and that there are detectable differences in such networks as a consequence of preterm birth [71]. In addition, because of the safety of MRI for both mother [72,73] and fetus [74], FC of the fetal brain can be assessed in the womb prior to birth [75]. A comprehensive review of these studies has recently been published [18].

In contrast to task-based fMRI, rs-fMRI requires no active participation from the subject, no controlled stimulus presentation, and no comparison of activity levels [78], making it suitable for studying brain function in young children, including infants. The first rs-MRI studies in full-term infants were published by Lin, et al. [79] and Liu, et al. [80]. Several research groups then used rs-fMRI to study infants during the neonatal period and the first two years of infancy [11,13,79,[81], [82], [83], [84]]. These studies included heterogeneous subject groups with different sizes, investigating healthy, term-born infants and neonatal clinical populations of interest. Studies were both cross-sectional and longitudinal and acquisition and analysis techniques differed across institutions. Despite these differences in study populations and approaches for assessment of connectivity, consistent patterns emerged from them. In particular, these studies demonstrated that primary networks, such as the sensorimotor and affective brain areas were active at birth, consistent with behavioral observations [17,85,86]. In addition to the cortical networks, infant FC patterns of subcortical structures were characterized [13,87].

The spatial resolution of fMRI varies with the strength of the static magnetic field (B0; e.g., 1.5 T, 3.0 T) and scanning parameters. Typical fMRI voxel size is 3 × 3 × 3 mm (27 mm3) and in best case it is 2 × 2 × 2 mm (8 mm3). While such a spatial resolution is generally adequate for adult studies, given the small size of the infant's brain, it imposes limitations for detailed separation of specific brain regions [88].

Collecting high-quality rs-fMRI images typically requires a participant to remain without any motion throughout the scan, which lasts between 5 and 13 min [89]. Also, the results from FC measures can be dependent on sampling window, and have been shown to be increasingly more reliable with longer imaging windows [90]. In contrast, it has been shown that even small head movements during fMRI scanning might cause an underestimation of long-range connectivity and an overestimation of short-range connectivity [91]. In children as young as 4 years [[92], [93], [94]], motionless rs-fMRI may be achieved by providing instructions, practice, and incentives, so that they are awake and resting with eyes open or closed during the scan. For infants however, this is not an option [88].

Early studies in infants used sedation [95,96] and natural sleep [13,97]. Due to safety concerns associated with sedation in very young children, imaging of healthy normal infants is currently performed during natural sleep without sedation, which is safer and more acceptable to the infants/family and also practically less complicated [88]. These methods require infants to sleep in an environment with the loud noises of the MRI machine. In addition, previous research has shown that light sleep increases the connectivity patterns and changes the temporal and spatial properties of resting-state connectivity compared to the awake state [98,99]. An important consideration for imaging naturally sleeping infants is sleep tracking to find variations of sleep stages during the scan. In theory, this difficulty may also be overcome using MR-compatible EEG to simultaneously acquire MR and EEG signals [42,[100], [101], [102]].

3.2. Electroencephalography (EEG)

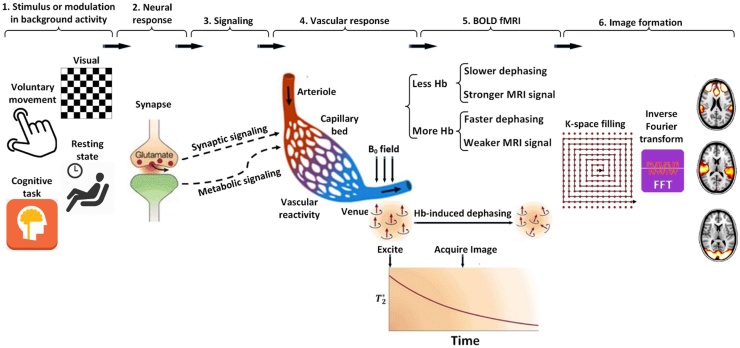

Electroencephalography (EEG) is an electrophysiological neuroimaging technique that measures the electrical activity generated by the human brain [103]. Miniscule electrical signals are the means of communication between neuronal cells in the brain. EEG measures the sum activity of these electrical signals conducted to the scalp (Fig. 4). Thus, in contrast to fMRI, fNIRS, and PET that indirectly measure brain activity (i.e., changes in perfusion, oxygenation, and cellular metabolism), EEG signals are generated directly by neuronal activity. Special electrodes are placed on the child’s head on specific anatomical locations. The conductivity between the electrodes and the scalp is often achieved through a conductive gel or special pads soaked into the water. It is a painless and harmless modality and commonly used in children with different ages. EEG has been used to study dynamical fluctuation of the brain activity at rest [103].

Fig. 4.

A basic EEG acquisition system is composed of (1) a set of electrodes to (2) extract the EEG time series from the scalp, (3) analog biomedical amplifiers with coupled analog low pass filters, analog-to-digital converters (A/D) [107], and (4) an interface with the data processing and display module. Brain waves measured by EEG mostly reflect electrical activity in the cortex, but include contributions from the whole brain.

Resting-state EEG has been used so far in two studies of infants [104,105] but neither measured FC. Tierney and colleagues [105] as well as Bosl and colleagues [104] used resting-state EEG to describe differences in quantitative EEG features between infants (6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months old) at high and low family risk of ASD, i.e., infants who had an older sibling with ASD. However, Orekhova and colleagues [106] used a visual task EEG to evaluate functional brain connectivity in 14-month-old infants with high and low family risk of ASD.

An interesting feature of EEG as a functional modality is its fine temporal resolution which is in the millisecond range [103]. The main limitations of EEG connectivity analysis are its spatial resolution and the fact that it does not provide an absolute measure of brain activity rather than potential differences between two locations on the scalp. EEG recordings are always sparse and thus no unique solution exists for the spatial location of the neural activity [108]. There are also considerable artifacts associated with EEG mapping, such as eye blinks, power line noise at 50 or 60 Hz, and muscular activity that confound connectivity estimates, especially those based on signal amplitudes [108]. Similar to fMRI, studies of brain connectivity using EEG are based on evaluating temporal dependencies between time series collected from the brain [108]. In contrast to fMRI, EEG connectivity is not usually affected by motion because the EEG electrodes are fixed on the scalp [106].

3.3. Magnetoencephalography (MEG)

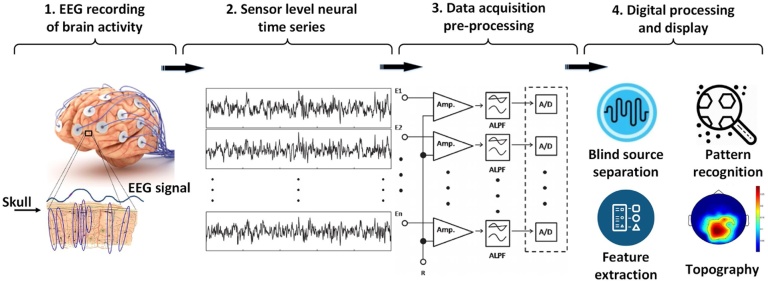

MEG complements EEG as the only other technique capable of directly measuring the developing brain neural activity in an entirely passive manner [109]. MEG is a non-invasive electrophysiological imaging technique used to measure very weak magnetic fields produced by electrical currents occurring naturally in the brain on a millisecond time scale [110]. These weak magnetic fields are measured by detection coils, which are inductively coupled to very sensitive magnetic field detection devices, called superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs). The magnetic fields generated by the neurons are located a few centimeters from the detection coils (Fig. 5). The spatial distributions of the magnetic fields are analyzed to localize the sources of the activity within the brain. The locations of the sources are superimposed on anatomical images, such as structural MRI, to provide information about both structure and function of the brain.

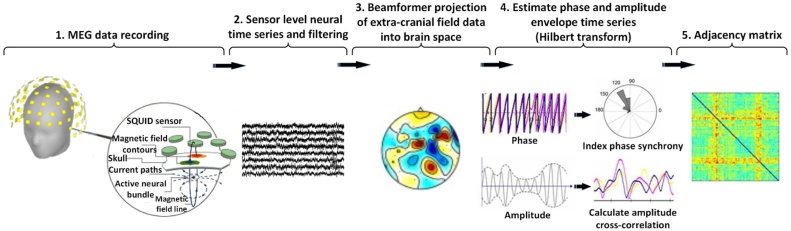

Fig. 5.

MEG data acquisition and processing: (1) MEG time series are recorded by sensors [111] and after a (2) filtering procedure, (3) transformed to source-space time series by a beamformer algorithm [112]. (4) The resulting time series is then filtered in the alpha-band (8–12 Hz) and its phase and amplitude is extracted via Hilbert-envelope computation, resulting in 90 alpha-power time series [113]. (5) The model is constructed by taking the same AAL brain parcellation used for source-reconstruction of the MEG signal, and putting a model node in the centre of each brain area and construction an adjacency matrix for the FC.

Compared to other neuroimaging techniques, MEG presents a unique set of important advantages [114]. Similarly, to EEG, MEG provides a direct measure of brain activity, but it is reference free. The preparation for a MEG recording is faster and easier, since brain activity can be measured immediately after placing the children’s head inside the special helmet. There is no need for sensors to be attached on the child’s head as with the EEG. More importantly, MEG signals are not distorted by skull conductivity [115], and less distorted than EEG by unfused regions of the cranial bone, such as fontanel or suture [116]. MEG provides high-resolution, temporal and spatial information about cortical brain activity: events with time scales on the order of milliseconds can be measured [117] and sources can be localized with millimeter precision [118,119]. However, despite the fact that MEG has better spatial resolution than EEG, because of a more restricted sensitivity to the alignment of electrical currents, it requires several assumptions to infer cortical source location [2]. EEG is sensitive to both tangential and radial components of a current source (i.e. the sulci and gyri) whereas MEG is most sensitive to activity originating in sulci [120]. Thus, comparison between EEG and MEG functional connectivity study should be interpreted with caution since the degree of cortical folding is less in the preterm and neonate. Unlike fMRI, MEG does not make any operational noise. While the current fMRI and MEG systems require absence of subject movement during recording, it is possible to develop motion measurement systems so that the subjects are allowed to move their heads during the MEG scan [121]. The main drawback of MEG is its extremely weak signal which is several orders of magnitude smaller than signals from background. Thus, special shielding is required to eliminate the interference that exists in a typical clinical environment.

MEG allows mapping cortical activity and provides a tool for exploring FC within the brain via the source localization. Additionally, frequency content of the neuronal oscillatory patterns can be extracted from MEG signals [103], therefore, it offers the ability to constrain connectivity analysis to particular frequencies of oscillation and to study rapidly changing or transient network structures [122].

MEG has been used for the brain imaging of the human infants [123,124] but, similar to fMRI, it suffers from the high cost of the recording instrumentation (>$1 million), therefore, it has not been used in common clinical settings.

Whole-head MEG systems are generally optimized/sized for adults. The smaller head sizes of infants and young children lead to an increased distance between the sites of neuronal activity and MEG sensors [125]. As a result, an adult MEG system does not provide optimal SNR in younger individuals [121]. MEG systems for infants and young children – 76-channel baby SQUID were developed in 2005 [26], in 2009 [126], its modified version [127,128], and Artemis123 [121]. Artemis123 is optimized to detect the brain activity in children from ∼6 to ∼36 months old. In the report by Boersma et al. [129], Artemis123 was used to record brain oscillations during an eyes-closed resting-state condition in early school age (4–7 years old) children. The aim of the study was to investigate whether and how oscillatory brain activities were different in 4 to 7 years old in children born small for gestational age (SGA) compared to those born appropriate for gestational age (AGA). In another study of rs-FC analysis using MEG, Sanjuan et al. [130] report the association between theta power in 6-month old infants and maternal prenatal posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) severity. Their findings suggest delayed cortical maturation in infants whose mothers had higher PTSD severity and, compared to infants born to mothers without PTSD, they develop poorer behavioral reactivity and emotional regulation.

3.4. Positron emission tomography (PET)

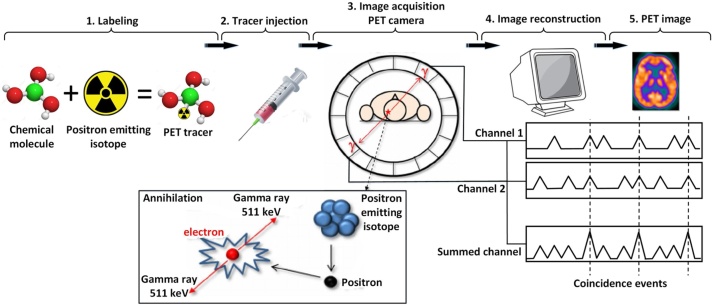

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a diagnostic functional imaging technique that allows the in vivo measurement of the distribution of a tracer labeled with a positron emitting nuclide. The importance of this technique in radiology originates from the existence of neutron-deficient isotopes of carbon (C-11), oxygen (O-15) and nitrogen (N-13), three of the major elements occurring in biological tissues. Small molecules such as water, carbon dioxide and ammonia can therefore be labeled with radioactive isotopes C-11, O-15, or N-13 without using artificial, inorganic elements, which potentially could modify the metabolic or physiological processes being studied (Fig. 6). This approach is in contrast to Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT), which requires biochemically unnatural radionuclides, such as Tc–99 m or Tl-201, which often complicates the interpretation of imaging data for characterization of physiological processes. The short half-life of C-11 (20.4 min), O-15 (2.07 min) and N-13 (9.96 min) is a further advantage for pediatric applications from a dosimetry point of view. However, since these short-lived isotopes are produced by a cyclotron, a cyclotron must be located in close proximity to the hospital or clinic where the scanner is located. In addition, longer-lived isotope of fluorine, the F-18 (110 min half-life) can be obtained from a remotely located cyclotron.

Fig. 6.

After producing an appropriate PET tracer (1) and the radiotracer injection (2), (3) positrons are emitted within the subject’s body, combine with nearby electrons and annihilate [131]. The result is a pair of 511-KeV gamma photons released in opposite directions. PET scanners use pairs of radiation detectors to measure the nearly simultaneous, coincident interaction of the 511-KeV photons. The data recorded by the scanner is a collection of coincidence detections. In the reconstruction step (4), a mathematical procedure is implemented to convert the acquired data to tomographic images (5).

A key property of positron emission tomography is the possibility of determining the position of positron annihilation by coincidental detection of two 511 KeV gamma photons traveling in 180° opposite directions and allowing for correction of photon attenuation in tissue (Fig. 6). As a result, accurate attenuation correction of coincidence data can be performed, permitting absolute quantification of local tracer concentration. These data can then be used for radiotracer kinetic modeling to yield quantitative values for various biochemical or physiological processes. Thus, PET imaging is the only methodology that allows determination of absolute values for physiological parameters such as blood flow (in units of ml/100 g/min), glucose consumption (umol/100 g/min) or receptor density (umol/100 g). Many PET tracers are now available for the study of various processes such as local cerebral metabolic rates for glucose utilization and protein synthesis, benzodiazepine receptor binding, serotonin synthesis, cerebral blood flow and oxygen utilization [132].

Resting-state PET has been widely used for diagnosis of many cerebral diseases in adults [[133], [134], [135]]. Only a few pediatric and even fewer neonatal PET studies have been presented to date [[136], [137], [138]]. Early application to the study of brain development revealed substantial qualitative changes in glucose uptake between the newborn and older child [139]. Notably, these studies demonstrated that the highest rates of glucose metabolism in the newborn brain are seen in the primary sensory and motor cortex, thalamus, brain stem and vermis, hippocampus/amygdala and occasionally the basal ganglia with very low activity noted in the remaining cerebral cortex [132,140]. The relatively low functional activity over most of the cerebral cortex during the neonatal period is in keeping with the relatively limited behavioral repertoire of newborns, characterized by the presence of intrinsic brainstem reflexes and limited visuomotor integration [141]. However, the relatively high metabolic activity of the amygdala and cingulate cortex in newborns suggests an important role of these limbic structures in neonatal interactions and, possibly, in emotional development [142]. Subsequently, increases of glucose utilization are seen by 2 to 3 months in the parietal, temporal, and primary visual cortex, basal ganglia, and cerebellar hemispheres, with the frontal cortex being the last brain area to display an increase in glucose consumption. These studies clearly demonstrate that in the first year of life, the ontogeny of glucose metabolism follows a phylogenetic order, with functional maturation of older anatomic structures preceding that of newer areas.

Despite its unquestionable strength in providing quantitative physiological data in the newborn and the developing brain, the main limitation of PET imaging in infants is the use of ionizing radiation from conventional positron-emitting radionuclides [132]. Although the exposure to radiation in the neonatal period is a matter of serious concern, most PET scans in neonates could be accomplished using significantly lower doses of radiotracers than in adults and are significantly below the radiotoxicity levels [132].

3.5. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS)

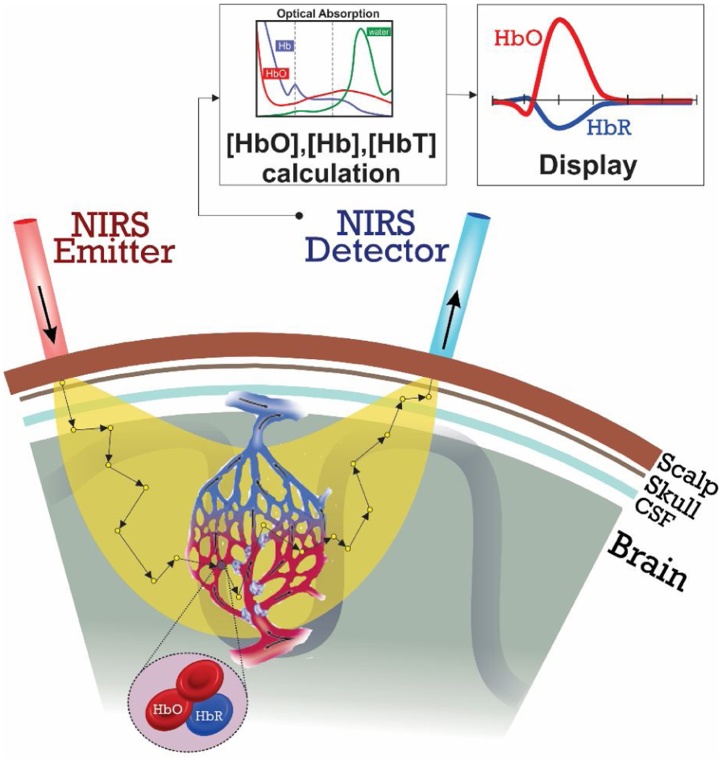

fNIRS takes advantage of living tissue’s absorption properties in the near-infrared range to measure changes in the local concentrations of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin ([HbO] and [HbR]) through the intact skull [143,144]. Light in the NIR spectral range (∼650–950 nm, ‘optical window’) can propagate relatively deeply (a few centimeters) into the brain tissue, mostly because NIR light is only slightly absorbed by water, collagen and proteins. fNIRS is performed by emitting near-infrared light into the scalp and detecting the transmitted light at certain positions (Fig. 7). fNIRS measures brain activity relying on neurovascular coupling (i.e. a close relationship between local neuronal and vascular activity [Fig. 8, part 1, optical imaging]), a similar mechanism used for the description of the BOLD effect in fMRI [145]. A transient increase in the brain activity induces an increase in the local glucose consumption and therefore induces a number of hemodynamic and metabolic adaptations. The BOLD signal is mainly sensitive to the deoxy-hemoglobin, while the fNIRS signal is sensitive to both species of hemoglobin (oxygenated and deoxygenated).

Fig. 7.

Schematic diagram of the fNIRS system. NIR-light are generated and guided to the human's head by optical fibers or cables. Another fiber bundle or cable directs diffusively reflected light from the head to detectors. A light detector captures the light resulting from the interaction with the chromophores (e.g. HbO, Hb), following a crescent-shaped path back to the surface of the skin.

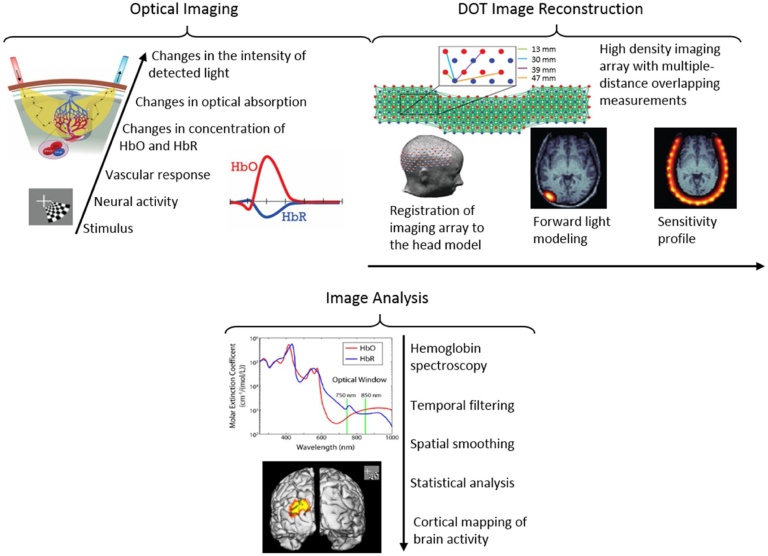

Fig. 8.

Brain mapping using diffuse optical tomography. Optical Imaging: Brain activity is recorded by sending near infrared light into the brain and recording diffusely reflected light. The vascular response to the neural activity results in changes in the concentration of oxygenated and de-oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO and HbR) which results in changes in the optical absorption coefficient and so changes in the intensity of diffusely reflected light. DOT Image Reconstruction: Source and detector arrangement in a high-density DOT imaging array. Example first to fourth nearest neighbor source-detector pairs are shown. Forward light propagation model is constructed by registering the imaging array to the head model. 3D images of absorption coefficient changes are reconstructed. Image Analysis: HbO and HbR signals are generated by hemoglobin spectroscopy. Temporal filtering and spatial smoothing are applied to the images. Additional statistical analyses are performed to generate cortical maps of the brain activity [177].

In contrast to PET, fNIRS is radiation free and unlike fMRI, is compatible with ferromagnetic implants, and provides a portable and wearable modality, therefore, suitable for all ages from premature neonates to the elderly; it can be performed at the bedside in various behavioral states. Long-term recordings can also be performed at the bedside. Unlike fMRI, subject immobilization is not required for fNIRS. Since fNIRS data can be acquired through non-metallic optical probes and do not require electrical coupling to the subject, measurements can be performed simultaneously with MRI [146] Fig. 8.

Regardless of the type of fNIRS instrument (continuous wave, time-resolved, frequency-domain), a light is generated and then channeled to the skin surface. Optical absorption in a biological tissue in NIR range is primarily due to hemoglobin. Hemoglobin has two forms: oxygenated and deoxygenated (HbO and HbR respectively). These chromophores have different absorption peaks (Fig. 8, image processing panel). At least two wavelengths in near-infrared spectrum are required for separate quantification of the concentration of both chromophores becomes possible (i.e. [HbO] and [HbR]). In addition to the stimulus-evoked responses [147], using sufficient number of channels, fNIRS provides a new tool to assess cerebral FC [29,148,149]. Similar to EEG and MEG, fNIRS does not generate any audio noise and thus, unlike fMRI, there is no cortical activation related to the acoustic noise. This is an important advantage in resting state studies, particularly for the investigation of FC in a developing brain [150,151].

In contrast to EEG and MEG, similar to fMRI and PET, fNIRS signal is not restricted to the neurons oriented in particular directions (i.e. pyramidal cells). Interneurons, which are highly solicited in the functioning brain have a closed field structure [152] and are therefore electrically and magnetically invisible, although they are known to be highly metabolically active [153].

In fNIRS the emitted photons must pass through different structures; a common problem for hemodynamic measurements in fNIRS concerns the optical properties of these structures. The optical properties of scalp, skull and CSF differ significantly in adults and are not completely defined [154,155]. They are largely unknown in infants. In addition, maturation is a dynamic process in the first months of life and these different tissues undergo maturational process such as ossification (skull), myelination (white matter) and changes in chromophores type [fetal hemoglobin (HbF)] and their changes are associated with changes in optical properties. In neonates and children up to the age of two, the presence of the fontanel makes the assumption of homogenous tissue, inappropriate [156]. Because of the heterogeneous composition of the skull, temporal variations in local oxygenation assessed by fNIRS can be distorted [157]. Consequently, estimated resting-state FC can be altered. Besides the factors directly related to the structure and optical properties of tissues in neonates, other age-related developmental mechanisms must also be taken into consideration (see [158,159]) such as a different oxygen metabolic rate in non-myelinated brain tissue [160,161].

fNIRS recordings are also performed during clinical care to evaluate the effect of different types of medications [162]. Compounds such as anesthetics, or caffeine in premature infants, modulate neuronal network activities.

Hemodynamic modulations in the resting state as well as connectivity within and between functional networks depend on the subject’s level of alertness. This can be described as state-dependent coupling [163]. Simultaneous fNIRS–EEG recordings in rats have shown that evoked electrical and hemodynamic responses have higher amplitudes during quiet sleep than during the rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and the waking state [163]. As neonates mature, neuronal activity and neurovascular coupling in various sleep states change week by week [164].

fNIRS is limited to sources situated fairly close (3–5 cm) to the cortical surface [165]. The depth of measurement of fNIRS mainly depends on the source-detector distance [166]. In adults, the depth of the cortical surface relative to the scalp differs from one region to another, but does not exceed 2–3 cm. In adults, unlike fMRI, fNIRS is not suitable for examining structures such as the basal ganglia or for studying the relationship between cortical and subcortical structures. In premature neonates, these structures are theoretically reachable by the NIR light. In fact, the greatest distance across the head between the right and left parietal areas is about 65 mm at 26 weeks gestational age (wGA) and about 88 mm at 38 wGA.

Unlike fMRI, EEG, MEG and PET, the presence of hair significantly limits the quality of fNIRS signal. Hair absorbs NIR light which in turn reduces the intensity of light as it goes through the head and comes back to the surface, resulting in a lower SNR. In neonates, especially premature neonates, due to the scarcity of hair, this problem is less significant. The slight discrepancies between FC determined by EEG/MEG and by fNIRS in neonates might be due to this effect [167,168].

3.6. Diffuse optical tomography (DOT)

Diffuse optical tomography (DOT) is an advanced optical neuroimaging method that uses a dense array of sources and detectors to yield measurements from multiple source-detector distances and solves an inverse problem to transform these measurements to depth information, therefore forming three-dimensional images of hemodynamic activity (Fig. 8) [169]. Tomographic imaging facilitates separating signal contaminations due to vascular dynamics within superficial layers (e.g. scalp) and thus obtaining more reliable measures of cortical hemodynamic activity [143]. Using high-density imaging arrays, DOT has been able to achieve spatial resolutions comparable to fMRI [170,171]. Sensitivity and specificity of this modality have been examined repeatedly by evaluating its performance in mapping topographic organizations of sensory regions [170,172] and imaging higher order brain functions [173,174]. Combining higher spatial resolution with portability and non-invasiveness of fNIRS, high-density DOT holds promise to extend functional neuroimaging to longitudinal monitoring of brain function at bedside.

Several studies have established high-density DOT imaging of neonatal brain function at the bedside, in the normal newborn nursery or complex neonatal intensive care unit [29,175,176]. Since it is quiet and less sensitive to motion artifacts than fMRI, these studies did not require using a sedating medication. The first high-density DOT study of neonatal resting state networks measured FC within occipital regions of term and pre-term infants [29]. A significant finding was that the bilateral correlation pattern seen within visual cortex of healthy infants was disrupted specifically in an infant with occipital stroke. This study was limited in its imaging field of view (FOV) but successfully showed the potential for clinical utility of high-density DOT. In a recent effort, the FOV was extended to enable mapping multiple resting state networks in newborns [176]. Quantitative and qualitative cross-modality comparisons of these results with subject-matched fMRI connectivity results, within a cohort of healthy full-term infants, showed a strong congruence emphasizing the supremacy of high-density DOT for neuroimaging at the bedside.

Current high-density DOT systems do not provide full-head coverage, particularly because extending the coverage while maintaining the high sampling density introduces significant challenges related to cap ergonomics and management of fiber bundles [174]. Fiber-less systems seem to be the next generation of high-density DOT systems that can overcome these challenges [178]. Development of high-density caps that cover whole head would not guarantee imaging of the whole brain because of an important limitation that all optical neuroimaging technologies face: limited depth of penetration. This limitation originates from the diffuse nature of photon migration through tissue, which dramatically decreases the sensitivity to subcortical brain activations occurring subcortically. Despite this limitation, cost, quietness, portability and metal-compatibility are major advantages of optical imaging, as compared to fMRI, in clinical and longitudinal studies of developing brain. Among other portable brain imaging systems explained above, such as fNIRS and EEG, high-density DOT is superior in terms of spatial resolution and brain specificity.

3.7. Functional ultrasound imaging

In ultrasound (US) imaging, a part of the body is exposed to pulsed ultrasonic waves and the amplitude of the ultrasonic echoes backscattered by tissues or fluids is measured. In conventional ultrasound imaging, the tissue is scanned line by line with an ultrasound beam. Line by line scanning is a slow process, especially when an US image needs to be obtained from a large-field of view (in the order of centimeters). A kilo-hertz frame rate is required if the blood dynamics need to be imaged. Therefore, either a small part of the tissue is used for scanning (limited field of view) or the scanning is performed for a much smaller number of pixels (limited sensitivity) [179].

In functional US (fUS) imaging [180], plane-wave illumination is used as opposed to focused beam scanning. A large-field image (in centimeter range) is obtained from a single plane-wave emission in the same acquisition time as focused beam. This strategy increases the number of samples acquired per pixel. By utilizing a set of tilted planar illuminations, acquiring the images and coherently summing the resulting set of images, a ‘compound' ultrasonic image is produced with much finer resolution and lower noise than the one produced by a conventional US [179], [181], [182]. Using fUS imaging, transient changes in blood volume in the brain at a high spatiotemporal resolution (kilohertz frame rate) is feasible. Recently, Demene et al. [183] have developed a portable customized and noninvasive fUS imaging system that is capable of continuous video-EEG recording and fast ultrasound imaging of the brain microvasculature in newborn babies. They monitor (through fontanel) brain activity and neurovascular changes in infants with abnormal cortical development using a bed-side fUS imaging system. Functional ultrasound imaging however has been successfully used for monitoring brain activity in newborns, it has not yet been used for measuring functional connectivity in infant brain. However, considering the recent findings, such accomplishment should not be too far away [184].

3.8. Photoacoustic tomography (PAT)

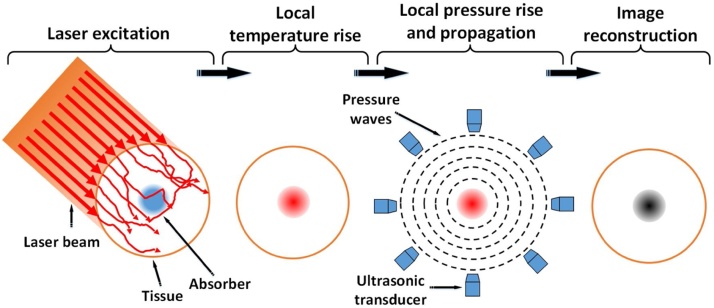

Photoacoustic Imaging (PAI) is a promising technique that provides noninvasive detection of structural, functional and molecular anomalies in biological tissue [185]. PAI combines the technological advances of both optical and acoustic imaging, i.e., the high intrinsic contrast of optical imaging and the spatial resolution of ultrasound imaging [186]. Every material, including bodily substances, has a specific optical absorption coefficient unique to endogenous chromospheres in cells or tissue [187,188]. The substance to be imaged is illuminated by a nanosecond pulsed laser of a specific wavelength at which the absorption coefficient of the subject is the highest (Fig. 9). Physical characteristics of the subject and the time scale of energy dissipation determine the required time scale over which the light must be delivered; related to the thermal and stress relaxation times. The photon absorption by the absorbing compartments causes a transient temperature change which leads to a thermal expansion, and consequently a localized pressure change p0 (Eq. (1)). These acoustic waves are detected by an ultrasonic transducer (Fig. 9).

| (1) |

| (2) |

Fig. 9.

Process of a photoacoustic tomography generation.

Grueneisen parameter in Eq. (1), Γ, relates the pressure increase to the deposited optical energy and is a dimensionless unit. A is the specific optical energy deposition; ηth is the percentage of light energy converted into heat, μa, is the optical absorption coefficient, and F is the optical fluence. Pressure change is dependent on the optical energy deposition which is the product of absorption coefficient of the subject and the incident optical fluence. Eq. (2), describes the PA wave propagation.is the pressure at location r and time t; T is the temperature rise, and ν is the velocity of sound in the medium [189].

Photoacoustic imaging of the brain is based on the acoustic detection of optical absorption from tissue chromophores, such as oxy-hemoglobin (HbO) and deoxy-hemoglobin (HbR) [190,191]. PAI can simultaneously provide high-resolution images of the brain vasculature and hemodynamics [192,193]. Photoacoustic technique is a scalable imaging technique, i.e., from photoacoustic microscopy (PAM) to photoacoustic tomography (PAT). PAM is an appealing imaging modality for shallow targets as it gives detailed information of vascular, functional, and molecular aspects [194,195] of biological samples both ex-vivo and in-vivo [31]. PAT is used for deep tissue imaging applications where coarse resolution (∼50 to 200 μm) is acceptable. PAT can potentially be used for neonatal brain imaging. In PAT, a diffused high energy pulsed laser, through bulk optics or optical fiber bundle, covers the imaging target, e.g., head, and photoacoustic waves are generated. The waves around the tissue are collected by wideband ultrasound transducers (Fig. 9) [196]. The detection scheme can be realized by a linear array ultrasound transducer, a single ultrasound transducer which rotates around the sample, by spiral rotation of a transducer, by a stationary ring array of 128, 256, or by a number of transducers arranged as an arc array transducer or as a half or full hemispherical array. For neonatal brain imaging, a linear or a hemispherical transducer array can be used. The ultrasound waves collected from the object are measured and sent to a computer to be used by an image reconstruction algorithm [197,198], to form an image; in the case of hemispherical transducer array, a three dimensional map of brain activities is obtained [199].

Recently, photoacoustic computed tomography (PACT) of small animal brain has successfully been implemented [190,191,200,201]. In these studies, PACT was used for mapping the microvascular network of a mouse brain with the hemodynamic activities when the scalp and skull were intact with an imaging frame rate of 50 Hz at which the respiratory motions and heartbeats were captured well above the Nyquist sampling rate [193,201,202]. PACT employs non-ionizing electromagnetic waves to provide such structural, functional, and molecular contrasts with either endogenous or exogenous agents. FC photoacoustic tomography (fcPAT) of resting-state functional connectivity (RSFC) has been studied in the mouse brain [199,200]. fcPAT was able to detect connectivity between different functional regions and even between sub-regions, promising a powerful functional imaging modality for future human brain research [[203], [204], [205]].

Compared with other deep imaging techniques such as functional connectivity DOT [206] or functional connectivity near infrared spectroscopy [207], fcPAT has a better spatial resolution. In addition, using a wide variety of optical biomarkers, molecular imaging can also be performed by photoacoustic imaging [31]. By comparison, fcMRI does not distinguish between increased blood oxygenation and decreased blood volume [208]. By combining high-resolution naturally co-registered RSFC, vascular, and molecular images, fcPAT allows investigators to study the origin of RSFC and its underlying neurovascular coupling, as well as the genetics behind neurological disorders. Although a few studies demonstrated the principle of fcPAT, future improvements can advance the technique [190,191,200,201]. For instance, fast wavelength switching lasers are commercially available and can be used to accurately quantify the hemodynamics by spectrally separating the contributions of oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin.

The main difference between fUSI and PAI is in the ability of fUSI to image blood flow rate in functionally active regions of the brain, but cannot differentiate between oxygenated or deoxygenated blood and cannot be used to determine regional brain oxygen extraction fraction. PAI can be used to determine regional brain oxygen extraction fraction in addition to what fUSI can do. In fact, both modalities should be used in parallel or “fused” to generate accurate quantitative parametric images of blood flow/oxygen extraction (or regional brain oxygen consumption).

One of the applications of PAI in neonatology is tissue oxygen saturation (SO2) measurement. SO2 measurement can be used for diagnosis, therapy planning, and treatment monitoring [[209], [210], [211], [212], [213]]. SO2 maps provide information about tissue hypoxia and evidence of oxygen availability in the circulatory system. As opposed to hypoxia-related probes such as PET [214] that their SO2 maps of hypoxic regions are susceptible to the time delay between the injection of the contrast agent and image acquisition [215], spectroscopy-based photoacoustic imaging methods could quantify the oxygen saturation solely based on hemoglobin as an endogenous contrast agent [[216], [217], [218], [219]].

Another advantage of PAI is its high chance of acceptance in the clinic. That is because the ultrasound imaging is extensively used in the current practice. With small modifications to an existing ultrasound probe, a photoacoustic probe can be built with almost the same look as an ultrasound probe. Such probe will require only a minimal training for nurses and physicians.

One of the main challenges in photoactinic imaging is the light penetration depth. There have been several attempts to find the most reliable wavelength for deep PA imaging. Some of these findings can be found in [199,[220], [221], [222], [223]]. Another challenge is the detection of ultrasound signals through the skull. The effects of dispersion and attenuation of the skull tissue have been explored in several studies [224,225]. PA signal broadening, signal shifting, and amplitude reduction are the main effects as a result of the skull tissue. In neonatal brain imaging in particular, because skull bones have not completely been fused together and have openings between them, so-called “fontanelles” [226], transfontanelle photoacoustic imaging is a more feasible methodology where the effect of the skull aberration can be ignored.

Using more sensitive ultrasound transducers, a higher number of transducers, faster data acquisition systems, higher energy laser with higher repetition rates (>50 Hz), and a more comfortable transducer-head coupling, a more practical PA system for neonatal brain imaging can be achieved. Finding the optimized wavelength for deep brain imaging, an effective skull aberration compensation algorithm [225,[227], [228], [229]], deconvolving the PA signal generated by the scalp and hair from that generated by the brain, and developing an optimum image reconstruction [197,198] and enhancement algorithms, are other issues to consider in translating PAI from preclinical studies to clinical practice. Due to its low-cost and maintenance compared with fcMRI and PET, the value of fcPAT should reconsidered as a contributor to functional neuroimaging of the newborn. The imaging target selectability (by changing the illuminating wavelength) is another major advantage of photoacoustic imaging. That is to mention the capability of PAI for imaging different compartments when an appropriate wavelength of light (according to the peak absorption of the compartment) is used. For instance, by using different wavelengths of light, PAI could measure the concentration of oxy- and deoxy- hemoglobin.

It is worth mentioning that, Hariri et al. [222], Herrmann et al. [230] and Wang et al. [221,231] have studied and demonstrated the utility of photoacoustic imaging in neonates. These studies demonstrated that the neonatal brain imaging through fontanel using photoacoustic technique is feasible. PA tomography on neonatal brain, even though the skull is thin (skull thickness is between 0.5 mm and 2 mm), requires the use of an accurate skull aberration correction algorithm [222,232]. Table 1 compares different characteristics of the neuroimaging modalities discussed in this review.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the neuroimaging modalities discussed in this review.

| Feature | fMRI | EEG | PET | MEG | fNIR | DOT | PAT | fUS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial resolution | 2–3 mm | 2–3 cm | 4 mm | <1 cm | 10–30 mm | 5–10 mm | 50–500 μm | 100–500 μm |

| Temporal resolution | ∼1 s | <1 ms | ∼30–40 s | <1 ms | 20 ms | 0.1–1 s [171,233] | 0.02–2 s | 1 ms |

| Non-Invasive | Yes | Yes | Noa | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Measurement | Hemodynamic activity | Electrical signal |

Metabolic activity | Magnetic signal | Hemodynamic activity | Hemodynamic activity | Hemodynamic activity | Hemodynamic activity |

| Expensive | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Neural activity measurement | Indirect | Direct | Indirect | Direct | Indirect | Indirect | Indirect | Indirect |

| Portable | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Long term recording | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sensitive to motion artifact | Yes | No | Yes | Less than fMRI | Yesb | Yesb | No | No |

| Multi-modal capability | DOT, EEG, fNIR, PAT, PET | DOT, fMRI, fNIR, MEG, PET | EEG, fMRI, fNIR, PAT | EEG, fNIR | EEG, fMRI, MEG, PAT, PET | EEG, fMRI, MEG, PAT, PET | EEG, fMRI, MEG, PAT, PET, fUS | EEG, PAT, PET |

| Brain coverage | Whole brain | Cortex | Whole brain | Cortex | Cortex | <3 cm into the brain (/Cortex) | One slicec | One slice |

| Loudness | Noisy | Silent | Silent | Silent | Silent | Silent | Silent | Silent |

It can be considered as a minimally invasive procedure (need of extrinsic contrast injection).

Strong head motion can lead to poor coupling between the scalp and the optodes, which alter the measured signal.

This information is for the transfontanelle photoacoustic imaging system.

4. Summary and conclusions

It is well understood that timely interventions are critical in minimizing long-term neurodevelopmental disabilities in high-risk newborns, and advanced non-invasive modalities and analytical approaches have been adapted from the adult literature to assess neonatal brain function. Advances in imaging modalities have improved our understanding of how functional networks develop during the neonatal period in the normal brain, and how mechanisms of brain disorder and recovery may function in the immature brain. FC among brain regions is used to explore brain networks. FC is the statistical association of neuronal activity time courses across distinct brain regions, supporting specific cognitive processes. When these associations are examined in the absence of any external task, they demonstrate whether and how different brain areas are synchronized to form functional networks at rest. Resting-state networks, also called intrinsic networks, are spatially distinct regions of the brain that exhibit a low-frequency temporal coherence and provide a means to depict the brain’s functional organization.

Different neuroimaging modalities have been employed to study the human infant brain at rest. These modalities provide complementary information about the brain’s function and structure. Similar results obtained across different modalities and analysis protocols increase the confidence in the knowledge gained.

The major neuroimaging modalities that are reviewed here are fMRI, EEG, MEG, PET, fNIRS, DOT, fUS, and PAT. We summarized the major components of each modality and some of the problems faced by these techniques in the clinical setting. Although all of the above modalities record the same physiological phenomena, they are based on different detection methods. They have different spatial and temporal resolutions and different noise characteristics, especially when they are used to study infants. These neonatal neuroimaging modalities have demonstrated a great promise to explore the structure and function of the infant brain. Of note that, the reproducibility of FC patterns within and across subjects is still an issue for imaging modalities.

Multimodal approaches might improve our understanding of the RSNs by measuring dynamic interactions between brain areas at a multimodal-multiscale level. Multimodal methods provide high temporal and spatial resolution and offer unique opportunities for studying FC in neonates. Such techniques compromise the advantages of one technique while compensating for the disadvantages of the other.

We also introduced photoacoustic tomography as a complimentary functional and molecular neonatal neuroimaging modality potentially for imaging neonate’s brain. PAT is low-cost, portable and uses non-ionizing light. It holds an advantageous over other imaging modalities that cannot be used at the bed-side. Furthermore, the ability to image various fluorescence/absorber labeled targeted contrast agents (i.e., receptor and transporter ligands, enzyme substrates, etc.) provides an unprecedented opportunity for molecular imaging of various molecular and cellular-biological processes without the ionizing radiation of PET and other nuclear imaging modalities, or without complex hyperpolarization equipment required for MRI spectroscopy imaging. Given the preclinical findings and the many advantages of this modality, the value that PAT can bring to patients in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) is promising. We believe, the most impact of PAI imaging will be for regional/localized imaging (not the whole body), such as functional and molecular imaging of neonatal brain.

Together these neuroimaging modalities could vastly improve our understanding of the normally and abnormally developing newborn brain, bringing the potential for practice and therapies that can improve neurodevelopmental outcomes.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Elnaz Alikarami, Ali Hariri, Dr. Sasan Bahrami, and Dr. Armin Iraji for their input. This study was supported by the WSU’s Michigan Translational Research and Commercialization (MTRAC) program and Wayne State Startup fund.

Biographies

Ali-Reza Mohammadi-Nejad received his Ph.D. in biomedical engineering from the University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran. His bachelor's and master's degrees are in electronic and biomedical engineering, respectively. In 2017, he completed a two-year pre-doctoral fellowship at Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA. Currently, the focus of his research is the mathematical and computational modelling, especially, canonical correlation analysis (CCA) and partial least square (PLS), for fusion of multi-modal neuroimaging data such as anatomical magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), and functional MRI (fMRI).

Dr Mahdi Mahmoudzadeh is a faculty member at the University of Picardie Jules Verne. He received his PhD degree in Neuroscience from the University of Picardie in 2011. He has MS in biomedical engineering from Polytechnic of Tehran 2008. In particular, his current research interests include multimodal electro-optical neurophysiology and neurodevelopmental circuit.

Mahlega S Hassanpour, PhD, is a medical imaging scientist. Dr. Hassanpour received her PhD in physics from Washington University in St. Louis. During her PhD, she focused on developing DOT for neuroimaging of speech perception in people with cochlear implants. In her postdoctoral research at Laureate Institute for Brain Research, she developed multimodal pharmacological neuroimaging methods for studies of heart-brain connection and evaluated effects of cardiorespiratory stimulation of fMRI signals.

Pr Fabrice Wallois is the head of the unit of Functional Exploration of the Pediatric Nervous System in the Amiens University Hospital. He is also the Director of the Inserm U1105 group (Research Group on Multimodal Analysis of Brain Function) in University of Picardy Jules Verne. His research relates to the analysis and the maturation of the neural networks More recently, the characterization of the electric (EEG) and hemodynamic (NIRS) activities, their modulations and the localization of their sources in certain pathological situations in the child and notably in prematures are in the centre of his research.

Otto Muzik received his PhD Degree in Physics in 1998 from the University of Vienna, Austria. He spent his postdoctoral years first at the Nuclear Research Center in Julich, Germany and subsequently at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor working on quantitative methods in positron emission tomography (PET). In 1993 he joined the PET Research group at Children's Hospital of Michigan, Detroit. His research includes multimodality integration of advanced imaging techniques such as PET, MRI and DTI. He is Professor of Pediatrics & Radiology and PI or Co-Investigator on several NIH grants funded in the PET Imaging group.

Christos Papadelis is an Assistant Professor of Pediatrics in Harvard Medical School and Head of the Children’s Brain Dynamics laboratory in the Division of Newborn Medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital. Dr. Papadelis has more than ten years of experience in magnetoencephalography (MEG) and electroencephalography (EEG) technology with both adults and children. He received the Diploma in Electrical Engineering from the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece, in 1998, and his MSc and PhD in Medical Informatics, in 2001 and 2005 respectively, from the same institute. After his PhD graduation, he worked as Post-Doc Researcher in the Laboratory of Human Brain Dynamics at the Brain Science Institute (BSI) of RIKEN, Japan, from 2005 to 2008, and in the Center for Mind/Brain Sciences (CIMeC) of University of Trento, Italy, from 2008 to 2011. Back in 2011, he moved to Boston to join the Fetal-Neonatal Neuroimaging and Developmental Science Center (FNNDSC) as Instructor in Neurology and Manager of the BabyMEG facility, one of the very few MEG laboratories in the world fully dedicated to pediatric research. His research covers a broad range of studies on neuroscience, clinical neurophysiology, and biomedical engineering. Dr. Papadelis has a demonstrated record of productive research projects leading to more than 40 peer-reviewed research investigation articles and numerous articles in conference proceedings. He has funded projects from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the American Epilepsy Society, the Faculty Development Office in Harvard Medical School, and the Boston Children's Hospital. He is Academic Editor in PLOS ONE, ad-hoc reviewer in more than 40 journals, as well as guest editor in special issues of his field. Figures of his work have been selected as covers in scientific journals.

Anne Hansen received her MD from Harvard Medical School and her MPH from Harvard School of Public Health with a concentration in Clinical Effectiveness. She completed pediatric residency at Children’s Hospital Boston and fellowship in Newborn Medicine at Children’s Hospital Boston, Beth Israel Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Hansen joined the Harvard Medical School faculty in 1996 and is currently an Associate Professor of Pediatrics. Dr. Hansen has acted as Chair of the Harvard¬wide Neonatal Research Review Committee since 2004, and as Neonatology Consultant for the Rwinkwavu, Kirehe and Butaro Hospitals in Rwanda since 2010. She is a member of multiple committees, including the Boston Children’s Hospital Steering Committee (Medical chair), the Harvard Neonatal¬-Perinatal Medicine Training Program Fellowship Committee, the NICU Nutrition Committee, and the Neonatology Representative for the Advanced Fetal Care Center at Children’s Hospital Boston. She is also a Fellow in the American Academy of Pediatrics. Dr. Hansen has been nominated for the Harvard Medical School Prize for Excellence in Teaching twice, the Harvard Medical School Humanism in Medicine Award, and was awarded the Best Tutor of the Year Harvard Medical School Teaching Award.

Hamid Soltanian-Zadeh, PhD received BS and MS degrees in electrical engineering: electronics from the University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran in 1986 and MSE and PhD degrees in electrical engineering: systems and bioelectrical sciences from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA, in 1990 and 1992, respectively. Since 1988, he has been with the Department of Radiology, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI, USA, where he is currently a Senior Scientist. Since 1994, he has also been with the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, the University of Tehran, Tehran, Iran, where he is currently a full Professor. Prof. Soltanian-Zadeh is also affiliated with and has active research collaboration with Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA. His research interests include medical imaging, signal and image processing and analysis, pattern recognition, and neural networks. Dr. Soltanian-Zadeh is an associate member of the Iranian Academy of Sciences and has served on the study sections of the NIH, NSF, American Institute of Biological Sciences (AIBS), and international funding agencies.

Juri Gelovani clinical training has been in neurology, neurosurgery, neurotraumatology and neuroimaging. During the course of his career, he has served as a neurology and neuroimaging consultant in obstetrics and gynecology and neonatology. Dr. Gelovani is the pioneer of molecular-genetic in vivo imaging. His research interests include molecular PET imaging of cancer and the central nervous system using newly developed radiotracers, genomics and proteomics for cancer therapy, adoptive immunotherapy and regenerative stem cell therapies. He holds more than 15 patents, has published more than 160 papers and book chapters, and edited a major book in molecular imaging in oncology. Additionally, several diagnostic imaging compounds he developed are currently in clinical trials in cancer patients.

Mohammadreza Nasiriavanaki In 2012, Mohammad received his Ph.D. with Outstanding Achievement in Medical Optical Imaging and Computing from the University of Kent in the United Kingdom. His bachelor's and master's degrees with honors are in electronics engineering. He is currently an assistant professor in the Biomedical Engineering, Dermatology and Neurology departments of Wayne State University and Scientific member of Karmanos Cancer Institute. His area of expertise is designing medical devices for skin and brain diseases diagnosis using photoacoustic imaging and optical coherence tomography technologies.

References

- 1.Friston K.J., Frith C.D., Liddle P.F., Frackowiak R.S. Functional connectivity: the principal-component analysis of large (PET) data sets. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:5–14. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aslin R.N., Shukla M., Emberson L.L. Hemodynamic correlates of cognition in human infants. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015;66:349–379. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smyser C.D., Snyder A.Z., Neil J.J. Functional connectivity MRI in infants: exploration of the functional organization of the developing brain. Neuroimage. 2011;56:1437–1452. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vogel A.C., Power J.D., Petersen S.E., Schlaggar B.L. Development of the brain’s functional network architecture. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2010;20:362–375. doi: 10.1007/s11065-010-9145-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith-Collins A.P.R., Luyt K., Heep A., Kauppinen R.A. High frequency functional brain networks in neonates revealed by rapid acquisition resting state fMRI. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2015;36:2483–2494. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biswal B., Zerrin Yetkin F., Haughton V.M., Hyde J.S. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar mri. Magn. Reson. Med. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cole Advances and pitfalls in the analysis and interpretation of resting-state FMRI data. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 2010;4:8. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2010.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biswal B.B., Mennes M., Zuo X.-N., Gohel S., Kelly C., Smith S.M., Beckmann C.F., Adelstein J.S., Buckner R.L., Colcombe S., Dogonowski A.-M., Ernst M., Fair D., Hampson M., Hoptman M.J., Hyde J.S., Kiviniemi V.J., Kotter R., Li S.-J., Lin C.-P., Lowe M.J., Mackay C., Madden D.J., Madsen K.H., Margulies D.S., Mayberg H.S., McMahon K., Monk C.S., Mostofsky S.H., Nagel B.J., Pekar J.J., Peltier S.J., Petersen S.E., Riedl V., S.A.R.B Rombouts, Rypma B., Schlaggar B.L., Schmidt S., Seidler R.D., Siegle G.J., Sorg C., Teng G.-J., Veijola J., Villringer A., Walter M., Wang L., Weng X.-C., Whitfield-Gabrieli S., Williamson P., Windischberger C., Zang Y.-F., Zhang H.-Y., Castellanos F.X., Milham M.P. Toward discovery science of human brain function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:4734–4739. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911855107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buckner R.L., Andrews-Hanna J.R., Schacter D.L. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008;1124:1–38. doi: 10.1196/annals.1440.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fransson P., Skiöld B., Horsch S., Nordell A., Blennow M., Lagercrantz H., Aden U. Resting-state networks in the infant brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:15531–15536. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704380104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doria V., Beckmann C.F., Arichi T., Merchant N., Groppo M., Turkheimer F.E., Counsell S.J., Murgasova M., Aljabar P., Nunes R.G., Larkman D.J., Rees G., Edwards a D. Emergence of resting state networks in the preterm human brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010;107:20015–20020. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007921107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee W., Morgan B.R., Shroff M.M., Sled J.G., Taylor M.J. The development of regional functional connectivity in preterm infants into early childhood. Neuroradiology. 2013;55:2013. doi: 10.1007/s00234-013-1232-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smyser C.D., Inder T.E., Shimony J.S., Hill J.E., Degnan A.J., Snyder A.Z., Neil J.J. Longitudinal analysis of neural network development in preterm infants. Cereb. Cortex. 2010;20:2852–2862. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldoli C., Scola E., Della Rosa P.A., Pontesilli S., Longaretti R., Poloniato A., Scotti R., Blasi V., Cirillo S., Iadanza A., Rovelli R., Barera G., Scifo P. Maturation of preterm newborn brains: a fMRI-DTI study of auditory processing of linguistic stimuli and white matter development. Brain Struct. Funct. 2014;220:3733–3751. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0887-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Satterthwaite T.D., Wolf D.H., Roalf D.R., Ruparel K., Erus G., Vandekar S., Gennatas E.D., Elliott M.A., Smith A., Hakonarson H., Verma R., Davatzikos C., Gur R.E., Gur R.C. Linked sex differences in cognition and functional connectivity in youth. Cereb. Cortex. 2015;25:2383–2394. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhu036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomason M.E., Dennis E.L., Joshi A.A., Joshi S.H., Dinov I.D., Chang C., Henry M.L., Johnson R.F., Thompson P.M., Toga A.W., Glover G.H., Van Horn J.D., Gotlib I.H. Resting-state fMRI can reliably map neural networks in children. Neuroimage. 2011;55:165–175. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.11.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomason M.E., Thomason M.E., Dassanayake M.T., Shen S., Katkuri Y., Hassan S.S., Studholme C., Jeong J., Romero R. Cross-hemispheric functional connectivity in the human fetal brain. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;24 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3004978. (173ra24-173ra24) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van den Heuvel M.I., Thomason M.E. Functional connectivity of the human brain in utero. Trends Cognit. Sci. 2016;xx:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redcay E., Moran J.M., Mavros P.L., Tager-Flusberg H., Gabrieli J.D.E., Whitfield-Gabrieli S. Intrinsic functional network organization in high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2013;7 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Posner J., Park C., Wang Z. Connecting the dots: a review of resting connectivity MRI studies in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2014;24:3–15. doi: 10.1007/s11065-014-9251-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greene D.J., Koller J.M., Robichaux-Viehoever A., Bihun E.C., Schlaggar B.L., Black K.J. Reward enhances tic suppression in children within months of tic disorder onset. Dev. Cognit. Neurosci. 2015;11:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohammadi-Nejad A.-R., Hossein-Zadeh G.-A., Soltanian-Zadeh H. Structured and sparse canonical correlation analysis as a brain-wide multi-modal data fusion approach. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging. 2017;36(7):1438–1448. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2017.2681966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greicius M. Resting-state functional connectivity in neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2008;21:424–430. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328306f2c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe K., Hayakawa F., Okumura A. Neonatal EEG: a powerful tool in the assessment of brain damage in preterm infants. Brain Dev. 1999;21:361–372. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(99)00034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Samson-Dollfus D.A., Bendoukha H. Choice of the feference for EEG mapping in the newborn: an initial comparison of common nose reference, average and source derivation. Brain Topogr. 1989;2:165–169. doi: 10.1007/BF01128853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada Y., Pratt K., Atwood C., Mascarenas A., Reineman R., Nurminen J., Paulson D. BabySQUID. A mobile, high-resolution multichannel magnetoencephalography system for neonatal brain assessment. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2006;77:24301. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chugani H.T. A critical period of brain development: studies of cerebral glucose utilization with PET. Prev. Med. (Baltim) 1998;27:184–188. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1998.0274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sangild P.T. Intestinal macromolecule absorption in the fetal pig after infusion of colostrum in utero. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1999;45:595–602. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199904010-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White B.R., Liao S.M., Ferradal S.L., Inder T.E., Culver J.P. Bedside optical imaging of occipital resting-state functional connectivity in neonates. Neuroimage. 2012;59:2529–2538. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]