Abstract

Background and objective

Psychological states may interfere with visceral sensitivity. Here we investigate associations between psychosocial factors and visceral sensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Methods

Two IBS patient cohorts (Cohort 1: n = 231, Rome II; Cohort 2: n = 141, Rome III) underwent rectal barostat testing, and completed questionnaires for anxiety, depression, somatization, and abuse. The associations between questionnaire measures and visceral sensitivity parameters were analyzed in three-step general linear models (step1: demographic and abuse variables; step 2: anxiety and depression; step 3: somatization).

Results

Cohort 1. Pain threshold was positively associated with age and female gender, and negatively with adult sexual abuse and somatization. Pain referral area was negatively associated with age and positively with somatization and GI-specific anxiety, the latter effect mediated by somatization. Cohort 2. Pain threshold was positively associated with age and male gender, and negatively with adult sexual abuse. Pain intensity ratings were positively associated with somatization, female gender and depression, the latter effect mediated by somatization.

Conclusion

Somatization is associated with most visceral sensitivity parameters, and mediates the effect of some psychological factors on visceral sensitivity. It may reflect a psychobiological sensitization process driving symptom generation in IBS. In addition, abuse history was found to independently affect some visceral sensitivity parameters.

Keywords: Irritable bowel syndrome, visceral hypersensitivity, somatization, anxiety, depression, abuse, mediation effects

Key summary

Summarize the established knowledge on this subject?

Psychological distress, abuse history and somatization are of importance in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Psychological factors may interfere with visceral sensitivity.

What are the significant and/or new findings of this study?

Somatization is associated with various visceral sensitivity measurements in IBS.

Somatization mediates the effect of some psychological factors on visceral sensitivity in IBS.

Sexual abuse in adulthood has an independent effect on rectal pain thresholds in IBS.

Introduction

Psychological distress is recognized as an important factor in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).1 In the general population, about 50% of IBS patients report psychological symptoms, and in health care-seeking samples 40%–90% of IBS patients fulfil diagnostic criteria for a psychiatric disorder.2 The association between IBS and abuse was largely mediated by psychological factors in a population-based study.3 A history of sexual or physical abuse is linked to more severe pain, lower quality of life, and higher levels of extraintestinal symptoms in IBS.4 The latter are frequent in IBS and can be quantified using symptom checklists, where the total score often is referred to as somatization. Somatization is associated with impaired quality of life in IBS5 and can be conceptualized and operationalized as the presence of multiple medically unexplained symptoms (“functional somatization”).6 Somatization can also be conceptualized as a tendency to express psychological distress as bodily symptoms (“presenting somatization”).6 Both conceptualizations are not mutually exclusive. Sensitization processes in sensory pathways at various levels of the central nervous system (CNS), leading to hypersensitivity for visceral and/or somatic stimuli, are believed to constitute a key mechanism underlying somatization. At the level of the brain, such processes are highly intertwined with affective processes.1

Colorectal hypersensitivity is an important pathophysiological mechanism in IBS.1 It has been associated with overall IBS symptom severity, and pain and bloating in particular.7 Suggested mechanisms include sensitization of afferent neurons, sensitization of spinal cord dorsal horn neurons and altered processing and modulation of afferent signals at the level of the brain, which may be driven by psychological states.8 Despite the consistent findings of associations between psychological stressors, states, and traits on the one hand, and IBS status on the other, it remains unclear how these factors interact and how they affect IBS symptom generation. Colorectal sensitivity is a good candidate mediator, based on its putative links with both psychological processes and IBS symptoms. The literature regarding the association between psychosocial factors and rectal sensitivity in IBS is limited and inconclusive.7,9–12

In this study we aimed to investigate the association between abuse, psychological states and traits, and somatization, and visceral sensory processing. Although findings in IBS are mixed, based on findings in functional dyspepsia (FD),13 we hypothesized associations between abuse history, psychological states, and somatization on the one hand, and visceral sensitivity on the other. Further, we used stepwise general linear models (GLMs) to test somatization as a potential mediator on the effects of abuse history and psychological states, a mediator being a variable that fully or partially accounts for the relation between the predictor and the dependent variable.14

Methods

Patient inclusion

Individuals aged 18 to 75 (Cohort 1) or 65 (Cohort 2) were recruited from our outpatient clinic for functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorders at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Sweden, with a mixed secondary-tertiary care function. The patients came through self-referral or referral from another physician, mainly in primary care, for their IBS. Two different cohorts were recruited. In Cohort 1 patients were enrolled 2003–2007, and had IBS according to Rome II criteria.15 The patients in Cohort 2 were enrolled 2010–2013 and had IBS according to Rome III criteria.16 Two different cohorts were included to assess the generalizability of the findings across different versions of the diagnostic criteria, and different measurements of visceral sensitivity. Exclusion criteria can be found in the online supplementary material. The study protocols were approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg, Cohort 1 with application number S489-02 approved October 22, 2002, and Cohort 2 application number 731-09 approved January 25, 2010. All participants received verbal and written information, and signed an informed consent, before any study-related procedure took place. The study protocol conforms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki.

Barostat testing

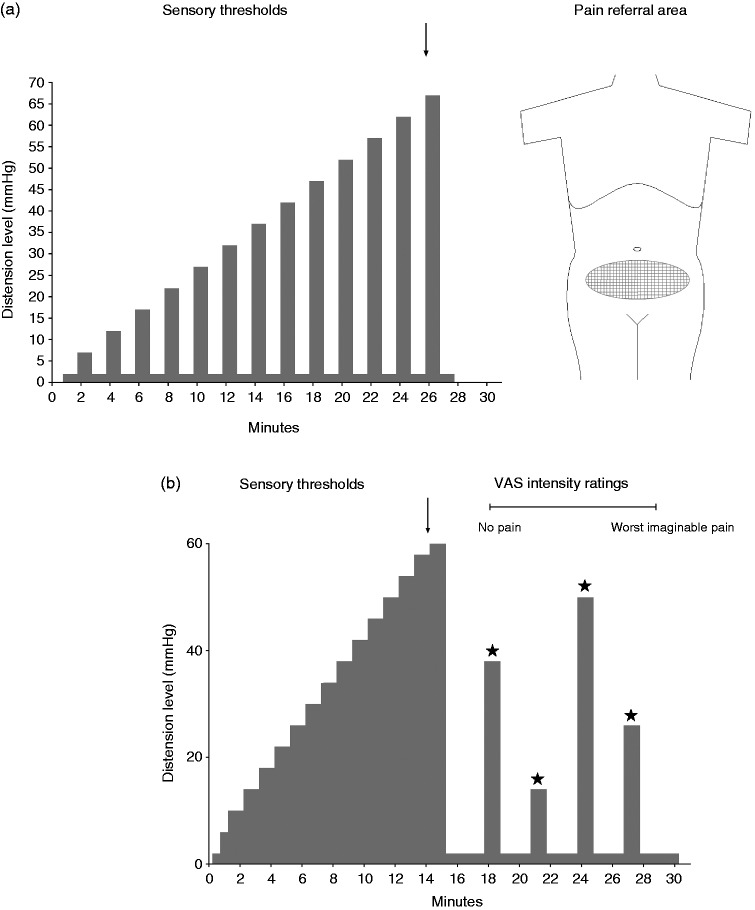

An overview of both distension protocols is given in Figure 1(a) and 1(b), respectively, and an overview of the visceral sensitivity measures obtained in each cohort in Table 1. Details on the barostat procedures are provided as supplementary material.

Figure 1.

Schematic drawings of the rectal distension protocols. (a) In Cohort 1, an AML protocol was used with phasic distensions of 30-second durations, separated by 30-second rest intervals with the balloon at the OP. At each distension step, the participants rated their perceived rectal sensation and indicated their painful sensations on a body map (indicated on both front and back of the body, with only the frontal image shown here). Arrows indicate sensory thresholds. (b) In Cohort 2, an AML protocol with step-wise successive increase in distension level was completed to assess sensory thresholds. After a resting period at OP, random phasic distensions at 12, 24, 36 and 48 mmHg above OP were performed during which participants scored intensity ratings for pain on a visual analog scale. AML: ascending method of limits; OP: operating pressure.

Table 1.

Overview of the different questionnaires and visceral sensitivity measures used in both cohorts.

| Measurement | Cohort 1 (n = 231) | Cohort 2 (n = 141) |

|---|---|---|

| Questionnaires (independent variables) | ||

| Abuse history | x (n = 124) | x |

| Visceral Sensitivity Index (VSI) | x | x |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | x | x |

| Somatization | ||

| Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-15) | x (n = 107) | x |

| Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) | x (n = 124) | |

| Visceral sensitivity measures (dependent variables)a | ||

| Pain thresholdb | x | x |

| Pain referral area | x | |

| Pain intensity rating at 36 mmHg rectal distension | x | |

All measures were obtained from rectal barostat investigations.

Different ascending method of limits barostat protocols were used in both cohorts (see supplementary materials for details).

Briefly, two different ascending method of limits (AML) rectal distension protocols7,17 were used. In Cohort 1, the pressure returned to operating pressure (OP) between distensions (Figure 1(a));7 in Cohort 2 it did not (Figure 1(b)).17 Only pain thresholds were used in this study. In Cohort1, after the AML, viscerosomatic referral areas for pain were assessed. This measurement is considered to reflect processing of sensory information at the level of the spinal cord.18 In Cohort 2, after the AML, the participants received four fixed distensions in random order (12, 24, 36 and 48 mmHg above OP) and completed visual analog scale (VAS) ratings for rectal sensations. In this study only pain ratings were used. Few participants completed all distensions, therefore we chose to analyze the 36 mmHg distension with last value carried forward if the 36 mmHg distension was not performed.

Questionnaires

An overview of the questionnaires completed in each cohort is given in Table 1.

Both cohorts completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),19 the Visceral Sensitivity Index (VSI)20 and a somatization questionnaire, either the Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15)21 or the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90R),22 both assessing the severity of somatic symptoms from different bodily systems.

The abuse questionnaire by Leserman et al.23 was used to obtain information about childhood physical, childhood sexual, adult physical and adult sexual abuse. In Cohort 1, the abuse questionnaire was added about halfway through the recruitment, when a publication on the putative link between abuse and rectal sensitivity became available,12 therefore abuse data are available only for a subsample (n = 124) of this cohort. All patients in Cohort 2 completed the questionnaire.

In Cohort 1, some patients completed PHQ-15 (n = 107), and some SCL-90 (n = 124, i.e. the subsample in which abuse data were available). Because of the different measurements, Z-scores were calculated, and this standardized value was used for each individual. In Cohort 2, all patients completed PHQ-15.

Statistical methods

All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4, significance level set to alpha = 0.05. Details of the statistical methods are provided as supplementary material.

The associations between visceral sensitivity measurements and questionnaire data were tested using bivariate association analyses. The variables with significant associations in these bivariate analyses were included as independent variables in different general linear models (GLMs) with visceral sensitivity measurements as dependent variables, controlling for age and gender. The independent variables were entered into the GLMs in three steps: step 1 abuse, step 2 anxiety and depression, and step 3 somatization. By subsequently adding the variables, we can evaluate independent effects and obtain an indication of putative mediation effects. If a variable changes from being significant to nonsignificant after adding a second variable (significant in the new model), it suggests that the first variable is mediated by the second variable, rather than having an independent/direct effect on the dependent variable.

Mediation in its strict sense implies a temporal order of the independent variable, mediator, and the dependent variable, which cannot be determined from this cross-sectional data set. The order in which the groups of variables were entered was determined based on previous studies suggesting this sequence of events: abuse → anxiety/depression → somatization → IBS (symptom severity).13,24 The temporal order of abuse preceding psychiatric symptoms/disorders has been shown in a longitudinal prospective study.25 Anxiety and depression predict the development of IBS symptoms, but not the reverse,26 and have a larger effect on functional somatic symptoms (i.e. somatization) than the other way around.27 In a general population sample without IBS symptoms, scoring high on indicators of psychological distress was predictive of having IBS 15 months later.28 These study results justify entering abuse before anxiety and depression, which in turn were entered before somatization.

When indication of mediation was found in the GLMs, mediation was specifically tested using bootstrapping using the purpose-built SAS macro INDIRECT29 (http://www.afhayes.com/spss-sas-and-mplus-macros-and-code.html).

Results

In Cohort 1, a total of 231 individuals were included (78.4% women). The subsample of 124 participants with abuse information had similar demography as the full cohort. In Cohort 2, a total of 141 patients were included (70.9% women). Descriptive statistics for the relevant variables in both cohorts are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for Cohort 1 and Cohort 2.

| Cohort

1 full sample (n = 231)

Subsample with abuse data (n = 124) |

Cohort 2 (n = 141) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Range | n (%) | Mean ± SD | Range | n (%) | |

| Age (years) | 35.9 ± 11.7 36.1 ± 12.2 | 19-67 19–67 | 34.7 ± 11.5 | 19-60 | ||

| Women | 181 (78.4) 94 (75.8) | 100 (70.9) | ||||

| Men | 50 (21.7) 30 (24.2) | 41 (29.1) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.4 ± 3.9 23.4 ± 3.7 | 16.2-38.2 17.3-38.2 | 23.5 ± 3.8 | 16.0-43.1 | ||

| Sexual abuse childhood | n/a 23 (19.0) | 25 (17.7) | ||||

| Sexual abuse adulthood | n/a 27 (21.8) | 44 (31.2) | ||||

| Physical abuse childhood | n/a 19 (16.8) | 36 (25.5) | ||||

| Physical abuse adulthood | n/a 16 (14.0) | 42 (29.8) | ||||

| GI-specific anxiety (VSI) | 38.7 ± 17.1 36.8 ± 16.5 | 3–74 8–72 | 43.3 ± 16.0 | 2–75 | ||

| Anxiety (HADS) | 8.2 ± 4.6 7.7 ± 4.6 | 0–21 0–19 | 8.3 ± 4.6 | 0–21 | ||

| Depression (HADS) | 5.1 ± 3.7 5.0 ± 3.6 | 0–20 0–16 | 5.2 ± 3.5 | 0–17 | ||

| Somatization (standardized on full sample) | 0.0 ± 1.0 −0.02 ± 0.96 | −1.9 to 3.2 −1.5 to 2.8 | ||||

| Somatization (PHQ-15) | 13.4 ± 4.7 | 3–30 | ||||

| Pain threshold (mmHg > OP) | 30.7 ± 11.1 33.9 ± 13.2 | 2–62 12–62 | ||||

| Pain threshold (mmHg) | 27.2 ± 8.7 | 12–56 | ||||

| Pain referral area (cm2) | 6.5 ± 7.6 4.7 ± 5.2 | 0.3–46.8 0.3–31.0 | ||||

| Pain intensity rating at 36 mmHg rectal distension (VAS) | 57.8 ± 31.8 | 0–100 | ||||

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index; OP: operating pressure; HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; GI: gastrointestinal; VSI: visceral sensitivity index; PHQ-15: Patient Health Questionnaire-15; VAS: visual analog scale.

GLMs

A detailed overview of all GLMs is displayed in Tables 3 and 4, showing parameter estimates (β-values), standard error (SE) and significance level for each variable in the different steps.

Table 3.

Results of general linear model analyses—Cohort 1.

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Step 1 demographics and

abuse |

Step 2 + anxiety and

depression |

Step 3 + somatization |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β ± SE | p value | β ± SE | p value | β ± SE | p value | ||

| Pain thresholda (n = 124) | Age | 1.58 ± 0.51 | 0.003 | 1.51 ± 0.52 | 0.004 | 1.57 ± 0.51 | 0.003 |

| Genderc | 23.7 ± 15.5 | 0.13 | 25.3 ± 15.5 | 0.11 | 31.5 ± 15.5 | 0.045 | |

| Sexual abuse adultd | −54.2 ± 16.1 | 0.001 | −48.3 ± 16.9 | 0.005 | −44.1 ± 16.8 | 0.01 | |

| anxiety (HADS) | −1.88 ± 1.65 | 0.26 | −0.94 ± 1.68 | 0.58 | |||

| GI-specific anxiety (VSI) | −0.16 ± 0.47 | 0.73 | 0.12 ± 0.48 | 0.81 | |||

| Somatization (standardized) | −15.7 ± 7.0 | 0.026 | |||||

| Pain referral areab (n = 231) | Age | −0.012 ± 0.006 | 0.036 | −0.012 ± 0.006 | 0.047 | −0.012 ± 0.006 | 0.040 |

| Genderc | 0.07 ± 0.17 | 0.70 | 0.05 ± 0.17 | 0.76 | −0.05 ± 0.17 | 0.76 | |

| GI-specific anxiety (VSI) | 0.009 ± 0.004 | 0.025 | 0.005 ± 0.004 | 0.22 | |||

| Somatization (standardized) | 0.17 ± 0.08 | 0.035 | |||||

Significant associations are shown in italics; effects which are mediated by somatization are underlined.

General linear model analysis on ranked dependent variable.

General Linear Model analysis on log transformed dependent variable.

Reference category = men.

Reference category = no abuse.

HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; GI: gastrointestinal; VSI: Visceral Sensitivity Index.

Table 4.

Results of general linear model analyses—Cohort 2.

| Dependent variable | Independent variable | Step 1 demographics and

abuse |

Step 2 + anxiety and

depression |

Step 3 + somatization |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β ± SE | p value | β ± SE | p value | β ± SE | p value | ||

| Pain threshold | Age | 0.21 ± 0.06 | 0.0006 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.002 | 0.20 ± 0.06 | 0.002 |

| Genderb | −4.5 ± 1.7 | 0.008 | −4.4 ± 1.7 | 0.01 | −4.1 ± 1.8 | 0.023 | |

| Sexual abuse adultc | −4.0 ± 1.6 | 0.016 | −4.0 ± 1.6 | 0.014 | −3.9 ± 1.6 | 0.018 | |

| GI-specific anxiety (VSI) | −0.09 ± 0.04 | 0.043 | −0.08 ± 0.05 | 0.086 | |||

| Somatization (PHQ-15) | −0.08 ± 0.17 | 0.65 | |||||

| VAS pain intensity 36 mmHg rectal distensiona | Age | −0.01 ± 0.32 | 0.98 | −0.07 ± 0.32 | 0.84 | −0.05 ± 0.32 | 0.87 |

| Genderb | 21.1 ± 8.5 | 0.014 | 21.9 ± 8.3 | 0.009 | 13.1 ± 9.1 | 0.15 | |

| Sexual abuse adultc | 8.6 ± 8.4 | 0.31 | 6.0 ± 8.3 | 0.48 | 5.8 ± 8.2 | 0.48 | |

| Depression (HADS) | 2.4 ± 1.2 | 0.042 | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 0.19 | |||

| GI-specific anxiety (VSI) | 0.19 ± 0.25 | 0.46 | 0.07 ± 0.25 | 0.79 | |||

| Somatization (PHQ-15) | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 0.032 | |||||

Significant associations are shown in italics; effects which are mediated by somatization are underlined.

General linear model analysis on ranked dependent variable.

Reference category = men.

Reference category = no abuse.

HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; GI: gastrointestinal; VSI: Visceral Sensitivity Index; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; VAS: visual analog scale.

GLMs Cohort 1

Pain threshold

Age, gender, sexual abuse in adulthood, anxiety, GI-specific anxiety and somatization were included in the full model F(6,119) = 4.96, p = 0.0001, R2 = 0.20.

In the final model, increasing age and female gender were independently associated with higher pain thresholds, whereas having experienced sexual abuse in adulthood, as well as somatization, were independently associated with lower pain threshold (i.e. increased sensitivity).

In this model there was no suggestion of mediational effects, hence no formal mediation testing was performed.

Pain referral area

Age, gender, GI-specific anxiety and somatization were included in the full model; F(4,228) = 3.59, p = 0.007, R2 = 0.06.

In the final model, age and level of somatization were negatively and positively associated with a larger pain referral area, respectively.

The positive effect of GI-specific anxiety (independent variable) on pain referral area (dependent variable) was mediated through somatization (mediator), β = 0.0035 ± 0.0017, 95% confidence interval (CI95%) 0.0005–0.0072 (does not include zero, hence significant indirect effect).

GLMs Cohort 2

Pain threshold

Age, gender, sexual abuse in adulthood, GI-specific anxiety and somatization were included in the full model; F(5,129) = 7.99, p < 0.0001, R2 = 0.24.

In the final model, increasing age was independently associated with higher pain thresholds, and being female and having experienced sexual abuse in adulthood were independently associated with lower pain threshold (i.e. increased sensitivity).

In this model there was no suggestion of mediation effects, hence no formal mediation testing was performed.

Pain intensity ratings

Age, gender, sexual abuse in adulthood, depression, GI-specific anxiety and somatization were included in the full model; F(6,134) = 4.17, p = 0.0007, R2 = 0.16.

In the final model, only increasing level of somatization was independently associated with higher pain intensity ratings.

The effect of depression (independent variable) on pain intensity ratings (dependent variable) was mediated through somatization, β = 0.79 ± 0.38, CI95% 0.14–1.70.

Discussion

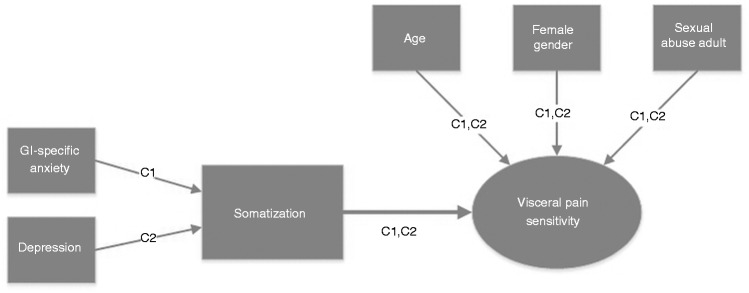

In summary, somatization was associated with several different measurements of visceral pain sensitivity in IBS (all but pain threshold in Cohort 2), and mediated associations between psychological states (GI-specific anxiety, depression) and pain sensitivity (Figure 2). More specifically, in two different cohorts using different rectal barostat protocols, age (positively), female gender (higher threshold in women in Cohort 1, lower in Cohort 2) and adult sexual abuse (lower threshold in abused individuals in both cohorts) were independently associated with pain threshold. Somatization had an independent effect in Cohort 1, but not in Cohort 2. The effect of GI-specific anxiety on pain referral area during rectal distension was mediated through somatization, which also mediated the effect of depression on pain intensity ratings during fixed intensity rectal distension.

Figure 2.

Summary of the results. Pain threshold, pain intensity ratings in response to fixed intensity stimuli and pain referral area, all determined during rectal distension, are different parameters to measure and quantify visceral pain sensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. Somatization was associated with all measurements of pain sensitivity. Factors with independent effect on pain sensitivity are visualized with arrows toward “Pain sensitivity.” Factors with effect on pain sensitivity mediated by somatization are indicated with arrows toward “Somatization.” Cohort 1 is denoted C1, and Cohort 2, C2. This figure summarizes the findings from different analyses with the different visceral sensitivity measurements as the dependent variables, and not from one single comprehensive model.

Somatization was measured using questionnaires assessing the severity of different somatic symptoms, and does not necessarily correspond to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) diagnosis of somatization disorder. This operationalization of somatization is most closely in line with the concept of “functional somatization,”6 as the questionnaires merely measure the experience of multiple symptoms. Even when operationalized as current or lifetime levels of somatic symptoms, somatization can be interpreted as a clinical manifestation of central sensitization processes,30 which may underlie hypersensitivity for visceral and somatic bodily stimuli. Central sensitization is defined as “an amplification of neural signaling within the central nervous system that elicits pain hypersensitivity.”31

IBS patients often have both visceral and somatic hypersensitivity, repetitive sigmoid distensions induce rectal hyperalgesia and increased viscerosomatic referral, and rectal anesthesia reduces both rectal and somatic pain, all of which indicates central sensitization in IBS.31 Psychological states interfere with this central sensitization process, as exemplified by IBS patients having dysfunctional descending pain modulatory mechanisms that, at least in part, is explained by psychological distress.32 In this study we have shown an association between psychological states and different readouts of visceral sensitivity in IBS, which were mediated through somatization. Based on the abovementioned, the psychobiological processes underlying these associations likely include central sensitization/pain amplification processes driven by dysregulations in emotional-arousal circuitry.33

Previous studies in IBS have not found an association between abuse history and colorectal hypersensitivity,11,12 nor between psychological distress or somatization and colorectal sensitivity.9,10 The differences in results between these studies and the present study could possibly be explained by differences in definition of abuse, measurement of colorectal sensitivity (as illustrated by the differences in the somatization-pain threshold association in our two cohorts using different barostat protocols), psychosocial factors included, or the populations studied. In most previous studies, with smaller sample sizes than the current study, colorectal sensitivity was dichotomized,9,10 which results in considerably lower statistical power compared to our approach to use continuous variables reflecting the sensitivity continuum.

Only a subgroup of IBS patients are hypersensitive to visceral and somatic34 stimulation, and a significant proportion do not have comorbid psychological symptoms or psychiatric disorders.2 Central sensitization can thus only be assumed to be an important pathophysiological factor in a subgroup of IBS patients. The variance in visceral sensitivity parameters explained by our models in this study was small or moderate, with the highest R2 value being 0.24. In other words, in the studied IBS population, at least 75% of the variance in pain sensitivity came from sources not accounted for in this study, which may include peripheral factors as well as central processes not sufficiently captured by the questionnaires included in this study.

This study suffers from a number of limitations that need to be addressed. The temporal order in the mediation analyses was hypothesized based on the literature, as justified in the Methods section. However, as alternative chains of events remain a possibility, we ran alternative mediation models, switching the position of the independent variable and the mediator. The direct path from the independent variable (somatization) to the dependent variables (measurements of visceral pain perception) remained significant when adding the mediators, and the indirect paths were all nonsignificant. This demonstrates that the chosen model with somatization as mediator is superior to alternative temporal orders.

Another concern is the possibility of omitting important variables. Adding measurements such as catastrophizing, neuroticism, coping strategies, and factors of childhood maltreatment other than abuse could plausibly change the results and/or improve the amount of variance explained.

The effects of gender on measures of visceral sensitivity were inconsistent in our cohorts. In Cohort 2, the results were straightforward, with female gender being significantly and consistently associated with increased sensitivity from the first step in the model, and either remaining independent or being mediated by somatization. In Cohort 1 the effect of gender became significant only in the last step of the analysis with pain threshold as the dependent variable (i.e. when controlling for all other variables), with female gender being associated with lower sensitivity (higher thresholds). We do not have a clear explanation for these discrepancies, but this is in line with mixed results in the literature regarding the effect of gender on rectal pain sensitivity.7,10,35

Different diagnose criteria, questionnaires and methods to quantify visceral sensitivity were used in both cohorts, which makes the divergent results more difficult to interpret. However, it could be argued that this makes the convergent results more generalizable. The difference between the two diagnoses criteria is mostly the duration and symptom frequency requirements, and the Rome III and Rome II criteria has been shown to have good agreement in a large cohort of Danish patients with a clinical diagnosis of IBS.36 The participants in this study are patients who sought care for their IBS at a secondary-tertiary health care center. Therefore, generalizing these results to the entire IBS population cannot be conducted without confirmatory studies in other IBS populations.

Although highly speculative, some possible implications of the present study in light of the existing literature can be suggested. There is strong evidence supporting that somatization is associated with chronic pain states and pain intensity ratings, and that somatization will improve with pain treatment,37 putatively by interfering with its underlying psychobiological central sensitization processes. Somatization questionnaires could possibly be used to identify IBS patients likely to benefit from drugs targeting central sensitization,31 although prospective studies are obviously needed to confirm this hypothesis. Exposure-based cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been shown to be effective in IBS, with its effects on GI symptoms being mediated by its effect on reducing GI-specific anxiety.38 Based on these findings and our current finding of an association between GI symptom-specific anxiety and visceral sensitivity, this type of CBT could potentially decrease visceral sensitivity. For a more detailed discussion on possible implications of our findings, please see the supplementary material.

Evaluating the associations between psychosocial stressors, psychological states, somatization and different measurements of visceral sensitivity, and exploration of putative mediation effects, has to the best of our knowledge not been performed before in IBS. This study therefore provides new and robust evidence showing that somatization is strongly associated with visceral sensitivity in IBS, either directly or by mediating its association with psychological states.

Conclusion

Both the descriptively measured concept of somatization and visceral hypersensitivity may reflect an underlying psychobiological sensitization process leading to the generation of both GI symptoms and the diverse extraintestinal symptomatology in IBS.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Lukas Van Oudenhove is a Research Professor funded by the KU Leuven Special Research Fund (Bijzonder Onderzoeksfonds, BOF).

Author contributions are as follows:

Cecilia Grinsvall: analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. Hans Törnblom: subject recruitment, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript. Jan Tack: study concept and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and critical revision of the manuscript. Lukas Van Oudenhove: study concept and design, statistical analyses, analysis and interpretation of data, statistical analysis, and critical revision of the manuscript. Magnus Simrén: study concept and design, subject recruitment, analysis and interpretation of data, acquisition of data, and critical revision of the manuscript, obtained funding, study supervision.

Conflict of interest

Cecilia Grinsvall has nothing to declare. Hans Törnblom has served as Consultant/Advisory Board member for Almirall, Danone and Shire. Jan Tack has given scientific advice to Almirall, AstraZeneca, Danone, Menarini, Novartis, Nycomed, Ocera, Ono pharma, Shire, SK Life Sciences, Theravance, Tranzyme, Xenoport and Zeria Pharmaceuticals, and has been a member of the Speaker bureau for Abbott, Almirall, AlfaWasserman, AstraZeneca, Janssen, Menarini, Novartis, Nycomed, Shire and Zeria. Lukas Van Oudenhove has nothing to declare. Magnus Simrén has received unrestricted research grants from Danone and Ferring Pharmaceuticals, and served as a Consultant/Advisory Board member for AstraZeneca, Danone, Nestlé, Chr Hansen, Almirall, Allergan, Albireo, Glycom and Shire, and as a speaker for Tillotts, Takeda, Shire and Almirall.

Funding

This study was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council (grants 13409, 21691 and 21692), the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation, AFA insurance, by an unrestricted grant from Ferring Pharmaceuticals and by the Faculty of Medicine, University of Gothenburg.

Ethics approval

None

Informed consent

None

References

- 1.Van Oudenhove L, Crowell MD, Drossman DA, et al. Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. Epub ahead of print 18 February 2016. DOI: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Surdea-Blaga T, Băban A, Dumitrascu DL. Psychosocial determinants of irritable bowel syndrome. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18: 616–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Talley NJ, Boyce PM, Jones M. Is the association between irritable bowel syndrome and abuse explained by neuroticism? A population based study. Gut 1998; 42: 47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leserman J, Drossman DA. Relationship of abuse history to functional gastrointestinal disorders and symptoms: Some possible mediating mechanisms. Trauma Violence Abuse 2007; 8: 331–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vu J, Kushnir V, Cassell B, et al. The impact of psychiatric and extraintestinal comorbidity on quality of life and bowel symptom burden in functional GI disorders. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014; 26: 1323–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Gucht V, Fischler B. Somatization: A critical review of conceptual and methodological issues. Psychosomatics 2002; 43: 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Posserud I, Syrous A, Lindström L, et al. Altered rectal perception in irritable bowel syndrome is associated with symptom severity. Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 1113–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anand P, Aziz Q, Willert R, et al. Peripheral and central mechanisms of visceral sensitization in man. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2007; 19: 29–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van der Veek PP, Van Rood YR, Masclee AA. Symptom severity but not psychopathology predicts visceral hypersensitivity in irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6: 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ludidi S, Mujagic Z, Jonkers D, et al. Markers for visceral hypersensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2014; 26: 1104–1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Davidoff AL, et al. Pain from rectal distension in women with irritable bowel syndrome: Relationship to sexual abuse. Dig Dis Sci 1997; 42: 796–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ringel Y, Whitehead WE, Toner BB, et al. Sexual and physical abuse are not associated with rectal hypersensitivity in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2004; 53: 838–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van Oudenhove L, Vandenberghe J, Vos R, et al. Abuse history, depression, and somatization are associated with gastric sensitivity and gastric emptying in functional dyspepsia. Psychosom Med 2011; 73: 648–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 2004; 36: 717–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, et al. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut 1999; 45(Suppl 2): II43–II47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longstreth GF, Thompson WG, Chey WD, et al. Functional bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cremonini F, Houghton LA, Camilleri M, et al. Barostat testing of rectal sensation and compliance in humans: Comparison of results across two centres and overall reproducibility. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2005; 17: 810–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mertz H, Naliboff B, Munakata J, et al. Altered rectal perception is a biological marker of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 1995; 109: 40–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983; 67: 361–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labus JS, Bolus R, Chang L, et al. The Visceral Sensitivity Index: Development and validation of a gastrointestinal symptom-specific anxiety scale. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004; 20: 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: Validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med 2002; 64: 258–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Derogatis L. SCL-90R administration, scoring and procedures manual-II, Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leserman J, Drossman DA, Li Z. The reliability and validity of a sexual and physical abuse history questionnaire in female patients with gastrointestinal disorders. Behav Med 1995; 21: 141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Tilburg MA, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE. Which psychological factors exacerbate irritable bowel syndrome? Development of a comprehensive model. J Psychosomat Res 2013; 74: 486–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spataro J, Mullen PE, Burgess PM, et al. Impact of child sexual abuse on mental health: Prospective study in males and females. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 184: 416–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koloski NA, Jones M, Kalantar J, et al. The brain-gut pathway in functional gastrointestinal disorders is bidirectional: A 12-year prospective population-based study. Gut 2012; 61: 1284–1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Janssens KA, Rosmalen JG, Ormel J, et al. Anxiety and depression are risk factors rather than consequences of functional somatic symptoms in a general population of adolescents: The TRAILS study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2010; 51: 304–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholl BI, Halder SL, Macfarlane GJ, et al. Psychosocial risk markers for new onset irritable bowel syndrome—results of a large prospective population-based study. Pain 2008; 137: 147–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 2008; 40: 879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phillips K, Clauw DJ. Central pain mechanisms in chronic pain states—maybe it is all in their head. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2011; 25: 141–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woolf CJ. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011; 152(3 Suppl): S2–S15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Piche M, Arsenault M, Poitras P, et al. Widespread hypersensitivity is related to altered pain inhibition processes in irritable bowel syndrome. Pain 2010; 148: 49–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayer EA, Labus JS, Tillisch K, et al. Towards a systems view of IBS. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 12: 592–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Verne GN, Price DD, Callam CS, et al. Viscerosomatic facilitation in a subset of IBS patients, an effect mediated by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Pain 2012; 13: 901–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Soffer EE, Kongara K, Achkar JP, et al. Colonic motor function in humans is not affected by gender. Dig Dis Sci 2000; 45: 1281–1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Engsbro AL, Begtrup LM, Kjeldsen J, et al. Patients suspected of irritable bowel syndrome—cross-sectional study exploring the sensitivity of Rome III criteria in primary care. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108: 972–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fishbain DA, Lewis JE, Gao J, et al. Is chronic pain associated with somatization/hypochondriasis? An evidence-based structured review. Pain Pract 2009; 9: 449–467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ljótsson B, Hesser H, Andersson E, et al. Mechanisms of change in an exposure-based treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. J Consult Clin Psychol 2013; 81: 1113–1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.