Abstract

The aim of this review was to explore the pharmacological activity of early tracheophytes (pteridophytes) as an alternative medicine for treating human ailments. As the first vascular plants, pteridophytes (aka, ferns and fern allies) are an ancient lineage, and human beings have been exploring and using taxa from this lineage for over 2000 years because of their beneficial properties. We have documented the medicinal uses of pteridophytes belonging to thirty different families. The lycophyte Selaginella sp. was shown in earlier studies to have multiple pharmacological activity, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, antidiabetic, antiviral, antimicrobial, and anti-Alzheimer properties. Among all the pteridophytes examined, taxa from the Pteridaceae, Polypodiaceae, and Adiantaceae exhibited significant medicinal activity. Based on our review, many pteridophytes have properties that could be used in alternative medicine for treatment of various human illnesses. Biotechnological tools can be used to preserve and even improve their bioactive molecules for the preparation of medicines against illness. Even though several studies have reported medicinal uses of ferns, the possible bioactive compounds of several pteridophytes have not been identified. Furthermore, their optimal dosage level and treatment strategies still need to be determined. Finally, the future direction of pteridophyte research is discussed.

Keywords: Pteridophyte, Fern, Alternative medicine, Selaginella, Human illness, Bioactive molecule

1. Introduction

Medicinal plants have been the source of remedies for the treatment of several illnesses since earliest times, and people from all continents have practiced the use of botanicals for millenia. Despite the significant growth in synthetic organic chemistry in the 20th century, over 25% of approved drugs in industrialized countries are obtained directly or indirectly from plants (Newman et al., 2000). In recent years, the search for phytochemicals with antioxidant, antimicrobial, or anti-inflammatory properties has been on the rise due to their potential use for the treatment of various chronic and infectious diseases (Halliwell, 1996). Therapeutic plants may be an alternative source of antimicrobial agents with important bioactivity against pathogenic and transmissible microorganisms, with fewer side effects than synthetic antibiotics (Berahou et al., 2007). Plant extracts have numerous secondary metabolites, such as phenolic components, that enhance biological activity. Plant secondary metabolites are known to possess antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, and some of them are categorized as generally recognized safe substances (Proestos et al., 2005). With the growing interest in these compounds, phytocompounds from therapeutic plants with some biomedicinal activity are in great demand (Chen et al., 2008; Pesewu et al., 2008; Prachayasittikul et al., 2008).

Ferns and their allies are one of the oldest major divisions of the Pteridophyta, and comprise over 12 000 species spread among 250 different genera (Chang et al., 2011). Traditionally, the biomedical system and Ayurvedic systems of medicine, named Sushruta (ca. 100 AD) and Charka (ca. 100 AD), suggested the use of some ferns in the Samhita texts. Pteridophytes are also used by physicians in the Unani system of medicine (Uddin et al., 1998). In the traditional Chinese system of medicine, several ferns are recommended by native doctors (Kimura and Noro, 1965). In more recent times, ethnobotanical and advanced pharmacological studies have been carried out on ferns and their allies by several investigators (Dhiman, 1998; Vasudeva, 1999; Reddy et al., 2001; Singh L et al., 2001; Gogoi, 2002; Singh M et al., 2008a, 2008b; Chen JJ et al., 2005; Chen K et al., 2005).

2. Phytochemicals of ferns and their distribution in other plant groups

The secondary metabolites, flavonoids, have anti-inflammatory properties through the inhibition of the cyclo oxygenase (COX) pathway (Liang et al., 1999). They were also found to have antioxidant, anti-cancer, and antimicrobial properties (Lin et al., 2008; Yoshida et al., 2008; Amaral et al., 2009; Lopez-Lazaro, 2009; Govindappa et al., 2011). Spider brake fern (Pteris multifida) has various bioactive flavonoids with heat-clearing, antipyretic, detoxification, antibiotic, anti-inflammatory, and antimutagenic activity (Lee and Lin, 1988). The entire plant of P. multifida contains various bioactive compounds including: luteolin-7-O-glucoside (Murakami and Machashi, 1985; Lu et al., 1999), 16-hydroxy-kaurane-2-β-D-glucoside (Liu and Qin, 2002), luteolin, palmitic acid, apigenin 4-O-α-L-rhamnoside (Lu et al., 1999; Qin et al., 2006), quercetin, hyperin, isoquercitrin, kaempferol, rutin (Lu et al., 1999; Wang et al., 2010; Hoang and Tran, 2014), and apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucoside (Lu et al., 1999; Hoang and Tran, 2014). Also, the cytotoxic bioactive compounds, pterosin sesquiterpenes, have been isolated from P. multifida (Shu et al., 2012). Bioactive terpenoids, especially the monocyclic sesquiterpene α-caryophyllene, were found in an ethanolic extract of Pteris tripartita (Baskaran and Jeyachandran, 2010). Sesquiterpenes form a significant group of secondary metabolites and have a varied range of medicinal activity, including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, cytotoxic, plant growth-regulatory, and antimicrobial properties (Baruah et al., 1994).

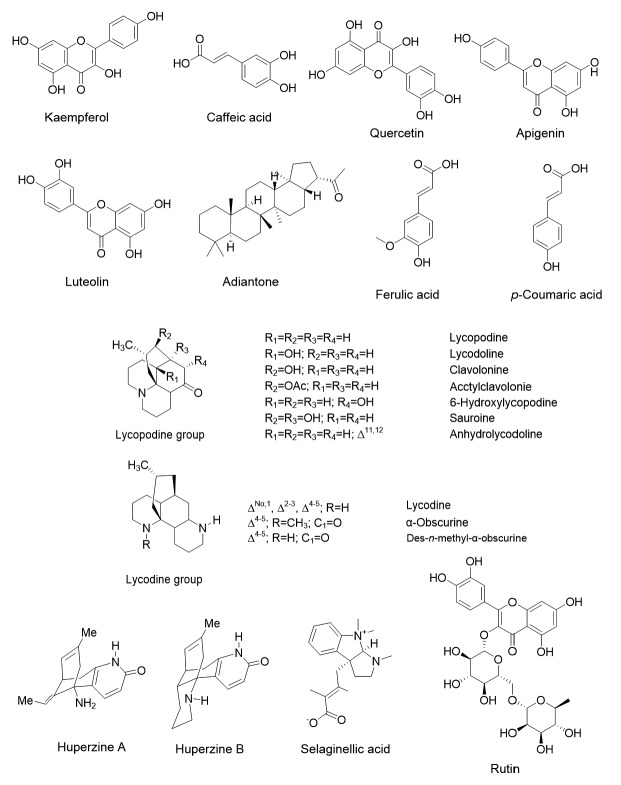

The anti-inflammatory activity of fatty acids such as myristic, palmitic, stearic, oleic-linoleic, and eicosatrienoic acids are widely known (Bremner and Heinrich, 2002). Stearic acid has been shown to have both anti-inflammatory and hepatoprotective effects (Pan et al., 2010). Baskaran and Jeyachandran (2010) found octadecanoic acid (a stearic acid) in an ethanol extract of P. tripartita. Pteridium aquilinum, thought to be a fern with potent anti-cancer properties, contains p-coumaric, p-hydroxybenzoic, caffeic, ferulic, vanillic, and protocatechuic acids (Michael and Gillian, 1984). Hydroxycinnamic acid, anthocyanins, total polyphenols, and flavonoids have been quantified in Stenochlaena palustris (Chai et al., 2012). Some bioactive flavones such as amentoflavone, robustaflavone, biapigenin, hinokiflavone, podocarpusflavone A, and ginkgetin, in Selaginella sp. were reported to have antioxidant, antivirus, and anti-cancer activity (Ma et al., 2001; Shi et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2011; Li S et al., 2014). Both the whole plant and mature spores of Lygodium japonicum are used for medical purposes in traditional Chinese medicine. For over 2000 years, L. japonicum has been used in China for the treatment of gorge gall, skin eczema, enteritis diarrhea, nephritis dropsy, urine calculus, and infection (Wynne et al., 1998). The foremost phenolic components, namely 4-hydroxycinnamic acid (p-coumaric), 3-methoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (ferulic), 3,4-dihydroxycinnamic acid (caffeic), 3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic, acid and 3-caffeoilquinic acid (chlorogenic), have been found in Polypodium leucotomos extracts (Gombau et al., 2006). The free radical scavenging bioactive principles viz. flavan-4-ol glycosides, abacopterins, huperzine A, isoquercetin, di-E-caffeoyl-meso-tartaric acid, flavaspidic acid PB, flavaspidic acid AB, flavan-3-ol, kaempferol, A-type proanthocyanidins, and afzelechin, have been derived from a few ferns including Abacopteris penangiana, Huperzia selago, Equisetum arvense, and Dryopteris crassirhizoma (Lee et al., 2003; Staerk et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2007; Mimica et al., 2008). Fig. 1 and Table 1 list the distribution of numerous bioactive compounds present in pteridophytes.

Fig. 1.

Bioactive compounds in pteridophytes

Table 1.

Distribution of bioactive compounds in pteridophytes

| No. | Pteridophyte | Bioactive compounds | Source(s) |

| 1 | Pteris multifida | Luteolin-7-O-glucoside, 16-hydroxy-kaurane-2-β-D-glucoside, luteolin, palmitic acid, apigenin4-O-α-L-rhamnoside, quercetin, hyperin, isoquercitrin, kaempferol, rutin, apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucoside, and pterosin | Murakami and Machashi, 1985; Lu et al., 1999; Liu and Qin, 2002; Qin et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2010; Shu et al., 2012; Hoang and Tran, 2014 |

| 2 | Pteris tripartita | α-Caryophyllene and octadecanoic acid | Baskaran and Jeyachandran, 2010 |

| 3 | Abacopteris penangiana | Flavan-4-ol, glycosides, and abacopterins | Zhao et al., 2007 |

| 4 | Pteridium aquilinum | p-Coumaric acid, p-hydroxybenzoic acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, vanillic acid, protocatechuic acid, kaempferol, quercetin, and apigenin | Michael and Gillian, 1984 |

| 5 | Selaginella sp. | Amentoflavone, robustaflavone, biapigenin, hinokiflavone, podocarpusflavone A, and ginkgetin | Ma et al., 2001; Shi et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2011; Li S et al., 2014 |

| 6 | Equisetum arvense | Isoquercetin, quercetin 3-O-glucoside, quercetin 3-O-(6''-O-malonylglucoside), 5-O-caffeoyl meso-tartaric acid, monocaffeoyl meso-tartaris acid, monocaffeoyl meso-tartaris acid, di-E-caffeoyl-meso-tartaric acid, hexahydrofarnesyl acetone, cis-geranyl scetone, thymol, and trans-phytol | Radulovic et al., 2006; Milovanovic et al., 2007; Mimica et al., 2008 |

| 7 | Polypodium leucotomos | 4-Hydroxycinnamic acid (p-coumaric), 3-methoxy-4-hydroxycinnamic acid (ferulic), 3,4-dihydroxycinnamic acid (caffeic), 3-methoxy-4-hydroxybenzoic acid, and 3-caffeoilquinic acid (chlorogenic) | Gombau et al., 2006 |

| 8 | Adiantum capillus-veneris | Adiantone, adiantoxide, astragalin, β-sitosterol, caffeic acids, caffeylgalactose, caffeylglucose, campesterol, carotenes, coumaric acids, coumarylglucoses, diplopterol, epoxyfilicane, fernadiene, fernene, filicanes, hopanone, hydroxy-adiantone, hydroxy-cinnamic acid, isoadiantone, isoquercetin, kaempferols, lutein, mutatoxanthin, naringin, neoxanthin, nicotiflorin, oleananes, populnin, procyanidin, prodelphinidin, quercetins, querciturone, quinic acid, rhodoxanthin, rutin, shikimic acid, violaxanthin, and zeaxanthin | Taylor, 2003 |

| 9 | Dryopteris crassirhizoma | Flaspidic acid PB and flavaspidic acid AB | Lee et al., 2003 |

| 10 | Cyathea gigantea | β-Sitosterol | Woyengo, 2009 |

| 11 | Cibotium barometz | Pterosins, terpenoids, sterides, flavones, glucosides, aromatic, and pyrone compounds | Wu et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2012 |

| 12 | Cyathea phalerata | Kaempferol-3-neohesperidoside, 4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl caffeic acid, 4-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl p-coumaric acid, 3,4-spyroglucopyranosyl protocatechuic acid, sitosterol β-D-glucoside, β-sitosterol, kaempferol, and vitexin | Hort et al., 2008 |

| 13 | Pteris vittata | Rutin, kaempferol monoglycoside, kaempferol diglycoside, quercetin monoglycoside, and quercetin diglycoside | Salatino and Prado, 1998; Singh et al., 2008b |

| 14 | Polypodium leucotomos | 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoic acid, chlorogenic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, chlorogenic acid, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, 4-hydroxycinnamic acid, 4-hydroxycinnamoyl-quinic acid, and ferulic acid | Garcia et al., 2006 |

| 15 | Angiopteris evecta | Angiopterioside | Twentyman et al., 1989 |

| 16 | Onoclea sensibilis | Kaempferol and quercetin | Harada and Saiki, 1955 |

| 17 | Matteuccia struthiopteris | Kaempferol and quercetin | |

| 18 | Equisetum ramoissimum | Apigenin and luteolin | |

| 19 | Lycopodium japonicum | Lycopodine-type alkaloids | He et al., 2014 |

| 20 | Lycopodium sieboldii | Sieboldine A | Hirasawa et al., 2003 |

| 21 | Lycopodium casuarinoides | Huperzine B and N-demethylhuperzinine | Shen and Chen, 1994 |

| 22 | Selaginella tamariscina | Caffeic acid, ferulic acid, vanillic acid, syringic acid, adenosine, umbelliferone, and amentoflavone | Bi et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2004; Woo et al., 2005 |

| 23 | Selaginella moellendorfii | Moellenoside B and selaginellic acid | Wang et al., 2009b; Feng et al., 2011 |

| 24 | Selaginella doederleinii | Apigenin and hordenine | Chao et al., 1987; Chen et al., 1995 |

| 25 | Dicranopteris linearis | Afzelin, quercitrin, isoquercitrin, astragarin, rutin, kaempferol 3-O-(4-O-p-coumaroyl-3-O-α-lrhamnopyranosyl)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranoside, and (6S,13S)-6-[6-O-acetyl-β-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→4)-α-L-rhamnopyranosyloxy]-13-[α-lrhamnopyranosyl-(1→4)-β-D-fucopyranosyloxy]cleroda-3,14-diene | Raja et al., 1995; Zakaria et al., 2008 |

| 26 | Psilotum nudum | Quercetin, kaempferol, amentoflavone, hinokiflavone, vicenin-2 psilotin, and 3'-hydroxypsilotin | Cambie and Ash, 1994 |

| 27 | Huperzia selago | Huperzine A | Staerk et al., 2004 |

| 28 | Huperzia serrata | Alkaloids: huperzine A and B | Liu et al., 1986 |

| 29 | Pityrogramma tartarea | 2'6'-dihydroxy-4,4'-dimethoxydihydrochalcone, kaempferol 7-methyl ether, and apigenin 7-methyl ether | Star and Mabry, 1971 |

| 30 | Pityrogramma calomelanos | ||

| 31 | Cheilanthes concolor | 7-O-Glycosides of apigenin, aglycone, 7-O-glycosides of luteolin, 7-O-glycosides of chrysoeriol, 3-O-glycosides of kaempferol, 3-O-glycosides of kaempferol, and 3-O-glycosides of quercetin | Salatino and Prado, 1998 |

| 32 | Cheilanthes flexuosa | ||

| 33 | Cheilanthes goyazensis | ||

| 34 | Doryopteris ornithopus | ||

| 35 | Pellaea cymbiformis | ||

| 36 | Pellaea gleichenioides | ||

| 37 | Pellaea pinnata | ||

| 38 | Pellaea riedelii | ||

| 39 | Pteris altissima | ||

| 40 | Pteris angustata | ||

| 41 | Pteris decurrens | ||

| 42 | Pteris deflexa | ||

| 43 | Pteris denticulata | ||

| 44 | Pteris plumula | ||

| 45 | Pteris podophylla | ||

| 46 | Pteris splendens | ||

| 47 | Pteris propinqua | ||

| 48 | Cyrtomium fortunei | Protocate chaldehyde, woodwardinsaure methylester, physcion, pimpinellin, ursolic acid, sitost-4-en-3-one, betulin, 3',4',5-trihydroxy-3,7-dimethoxyflavone, woodwardinic acid, sutchuenoside A, kaempferol-3,7-O-α-L-dirhamnoside, (−)-epicatechin, (+)-catechin hydrate kaempferol, crassirhizomoside A, and kaempferol-3-O-(3-O-acetyl-α-L-rhamnopyranoside | Yang et al., 2013 |

Marchantiophyta have a cellular oil body which produces numerous mono-, sesqui-, and di-terpenoids, aromatic compounds like bibenzyl, bis-bibenzyls, and acetogenins. Most sesqui-and di-terpenoids isolated from non-vascular plants (liverworts) are enantiomers of those present in vascular plants (Asakawa et al., 2013). Since 1960, studies have begun to identify triterpenoids in ferns too. Moreover, flavonoids are present in more than one genus of ferns and also occur in fern allies (Berti and Bottari, 1968). Pteridophytes are known to produce proanthocyanidins which are present in a polymerized molecular form, as tannins. Proanthocyanidins in higher groups of plants are formed by dihydroflavonol-4-reductase (DFR) using dihydroflavonols as substrate. The DFR enzyme has not been described in pteridophytes, but the genomic characterization of ferns has begun. DFR has been obtained from duplicate genes linked with primary metabolism; in this instance, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH)-dependent reductases are related to steroid metabolism (Baker and Blasco, 1992). Moreover, three divisions of the flavonoid pathway well-known in the bryophytes are also found in pteridophytes including procyanidins, prodelphinidins, and flavonols like kaempferol, quercetin, and myricetin (Markham, 1988). Acylphloroglucinol compounds are found only in the genus Dryopteris, which has been used in chemosystematic and phylogenetic studies (Widen, 1971; Widen and Britton, 1971a, 1971b). Flavonoids and phenolic compounds are the most general group of bioactive principles in plants, occurring in almost all plant parts, but mainly in photosynthesizing cells. These compounds are the main producers of the colors of blooming plants (Koes et al., 2005). In early studies, myricetin, quercetin, kaempferol, apigenin, luteolin, and gallic acid were reported in angiosperms including the Hamamelidae, Rutaceae, Eriocaulaceae, Lythraceae, and Velloziaceae (Grieve and Scora, 1980; Giannasi, 1986; Salatino et al., 2000). Several phenolic compounds, such as p-coumaric acid, caffeic acid, ferulic acid, protocatechuic acid, gallic acid, vanillic acid, and flavonoids like luteolin, apigenin, have also been identified in seagrasses (Subhashini et al., 2013). Apigenin, kaempferol, luteolin, myricetin, quercetin, and rutin were identified in some Iranian flowering plants from different families including the Leguminosae, Polygonaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Resedaceae, and Cyperaceae (Mitra, 2012). The bioactive flavonoids, kaempferol, luteolin, quercetin, quercitrin, isoquercitrin, hyperoside, and guaijaverin, have been derived from methanol extracts of Hypericum brasiliense (Rocha et al., 1995). In addition, kaempferol, myricetin, catechin, vitexin, orientin, isoquercitin, hyperside, isovitexin, luteolin-7-glucoside, rutin, kampferol-7-neohesp-eridoside, quercitin, luteolin, and apigenin have been identified in the angiosperm families Lytheraceae, Acanthaceae, Chenopodiaceae, Caprifoliaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Verbenaceae, Zygophyllaceae, Moraceae, Asteraceae, Urticaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Verbenaceae, and Mimosaceae (Khan et al., 2012). The evolution of flavonoids in land plants has been discussed from an enzymatic point of view. In ferns and their allies, proanthocyanidin and NADPH reductase are present for flavonoid synthesis while anthocyanidin and pterocarpan synthase have been reported in gymnosperms and angiosperms. Moreover, at two different levels, chalcone synthase, chalcone isomerase, anthocyanidin synthase, flavonol synthase, isoflavone synthase, and NADPH reductase are also involved in flavonoid synthesis (Stafford, 1991). These studies show that all land plants are related based on the evidence of shared secondary metabolites. The genetic relationships among genes in response to phytochemical synthesis in vascular and non-vascular plant groups should be studied further to understand their phytochemical evolution.

3. Activity of ferns

3.1. Antioxidant activity

Most of the pteridophytes are of great economic value, especially in medical, aesthetic, and food applications (Vasudeva, 1999). Table 2 summarizes the antioxidant activity of pteridophytes. The antioxidant activity has been reported for several fern species, namely Polystichum semifertile, Nothoperanema hendersonii, Braomea insignis (Chen K et al., 2005), some Chinese ferns (31 species) (Ding et al., 2008), Selaginella sp. (Gayathri et al., 2005), Polyopodium leucotomus (Garcia et al., 2006; Gombau et al., 2006), E. arvense, Equesitum sylvaticum (Milovanovic et al., 2007), A. penangiana (Zhao et al., 2007), Drynaria fortunei, Pseudodrynaria coronans, Davallia divaricata, Davallia mariesii, Davallia solida, Humata griffithiana (Chang et al., 2007b), Marsilea quadrifolia (Fig. 2c) (Ripa et al., 2009), Cheilanthes anceps Swartz (Chowdhary et al., 2010), Pteris ensiformis Burm. (Chen et al., 2007; Wei et al., 2007), P. multifida (Shyur et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2009a), P. tripartita (Baskaran and Jeyachandran, 2010), Dicranopteris linearis (Fig. 2d) (Zakaria et al., 2011), and Drynaria quercifolia (Fig. 2e) (Milan et al., 2013). Efficient antioxidant properties (0.02–0.12 mg/ml in 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) activity and 0.03–0.22 mg/ml in activity of 2,2'-azino-bis-(3-ethyl benzthiazoline-6-sulphonie acid diammonium salt (ABTS) radical scavenging) of several fern genera like Davallia, Hypolepis, Pteridium, Cyrtominum, Dryopteris, Polystichum, Dicranopteris, Lycopodium, Osmunda, Adiantum, Coniogramme, Polypodium, Pyrrosia, Pteris, Lygodium, Selaginella, Thelypteris, Athyrium, Matteuccia, Onoclea, and Woodsia have also been reported (Shin, 2010). According to Shin and Lee (2010), scavenging effects on DPPH and ABTS radicals were higher in methanol extracts from rhizomes than in those from aerial parts of Adiantum pedatum, Coniogramme japonica, D. mariesii, Cyrtomium fortunei, D. crassirhizoma, Polystichum polyblepharum, Polystichum lepidocaulon, Dryopteris nipponensis, Pteris cretica, P. multifida, and Polypodium nipponica.

Table 2.

Antioxidant potentials of pteridophytes

| No. | Plant name | Family name | Methods used | Source(s) |

| 1 | Polystichum semifertile | Dryopteridaceae | Xanthine oxidase, lipoxygenase activity, and ABTS•+ assay | Chen et al., 2005a |

| 2 | Nothoperanema hendersonii | Dryopteridaceae | ||

| 3 | Braomea insignis | Blechnaceae | ||

| 4 | Blechnum orientale | Blechnaceae | DPPH assay | Lai et al., 2010 |

| 5 | Selaginella sp. (n=3) | Selaginellaceae | In vitro lipid peroxidation, hydroxyl radical scavenging activity | Gayathri et al., 2005 |

| 6 | Polypodium leucotomus | Polypodiaceae | H2O2 and FRAP assays | Garcia et al., 2006; Gombau et al., 2006 |

| 7 | Equesitum sp. (n=5) | Equisetaceae | Total antioxidant capacity | Milovanovic et al., 2007 |

| 8 | Abacopteris penangiana | Thelypteridaceae | Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) assay | Zhao et al., 2007 |

| 9 | Marsilea quadrifolia | Marsileaceae | DPPH assay | Ripa et al., 2009 |

| 10 | Cheilanthes anceps | Sinopteridaceae | DPPH assay | Chowdhary et al., 2010 |

| 11 | Pteris ensiformis | Pteridaceae | DPPH and TEAC assays | Chen et al., 2007; Wei et al., 2007 |

| 12 | Pteris multifida | Pteridaceae | DPPH, superoxide scavenging activity | Shyur et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2009a |

| 13 | Pteris tripartita | Pteridaceae | DPPH, metal chelating activity, phosphomolydenum assay | Baskaran and Jeyachandran, 2010 |

| 14 | Dicranopteris linearis | Gleicheniaceae | DPPH assay | Milan et al., 2013 |

| 15 | Selaginella labordei | Selaginellaceae | In vitro xanthine oxidase inhibition | Tan et al., 2009 |

| 16 | Diplazium polypodioides | Athyriaceae | DPPH assay | Kshirsagar and Upadhyay, 2009 |

| 17 | Pteris vittata | Pteridaceae | DPPH and ferric reducing power assays | Lai and Lim, 2011 |

| 18 | Adiantum radianum | Pteridaceae | ||

| 19 | Acrostichum aureum | Pteridaceae | ||

| 20 | Cyathea latebrosa | Cyatheaceae | ||

| 21 | Cibotium barometz | Dicksoniaceae | ||

| 22 | Drynaria quercifolia | Polypodiaceae | ||

| 23 | Blechnum orientale | Blechnaceae | ||

| 24 | Diplazium esculentum | Athyriaceae | ||

| 25 | Nephrolepis biserrata | Nephrolepidaceae | ||

| 26 | Dicranopteris linearis | Gleicheniaceae | ||

| 27 | Dicksonia sellowiana | Dicksoniaceae | In vitro and in vivo antioxidant assays | Bora et al., 2005; Rattmann et al., 2011; Oliveira et al., 2016 |

| 28 | Microgramma vacciniifolia | Polypodiaceae | In vitro DPPH assay | Peres et al., 2009 |

| 29 | Polypodium leucotomos | Polypodiaceae | In vitro H2O2 assay | Gombau et al., 2006 |

| 30 | Davallia mariesii | Davalliaceae | In vitro DPPH, ABTS•+, and total antioxidant assays | Shin, 2010; Delong et al., 2011 |

| 31 | Cyrtomium fortunei | Dryopteridaceae | ||

| 32 | Dryopteris crassirhizoma | Dryopteridaceae | ||

| 33 | Dryopteris nipponensis | Dryopteridaceae | ||

| 34 | Polystichum lepidocaulon | Dryopteridaceae | ||

| 35 | Polystichum polyblepharum | Dryopteridaceae | ||

| 36 | Dicranopteris pedata | Gleicheniaceae | ||

| 37 | Osmunda cinnamomea var. fokiensis | Osmundaceae | ||

| 38 | Osmunda japonica | Osmundaceae | ||

| 39 | Adiantum pedatum | Pteridaceae | In vitro DPPH, ABTS•+, and total antioxidant assays | Shin, 2010; Delong et al., 2011 |

| 40 | Pyrrosia lingua | Polypodiaceae | ||

| 41 | Lygodium japonicum | Lygodiaceae | ||

| 42 | Thelypteris acuminate | Thelypteridaceae | ||

| 43 | Athrium niponicum | Athyriaceae | ||

| 44 | Onoclea sensibilis var. interrupta | Onocleaceae | ||

| 45 | Matteuccia struthiopteris | Onocleaceae | ||

| 46 | Aleuritopteris flava | Pteridaceae | DPPH, ABTS•+, ferric reducing power, and metal chelating assays | Gupta et al., 2014 |

| 47 | Pteris scabristipes | Pteridaceae | ||

| 48 | Adiantum edgeworthii | Pteridaceae | ||

| 49 | Lindsaea odorata | Dennstaedtiaceae | ||

| 50 | Microlepia rhomboidea | Dennstaedtiaceae | ||

| 51 | Microlepia hallbergii | Dennstaedtiaceae | ||

| 52 | Asplenium khasianum | Aspleniaceae | ||

| 53 | Diplazium esculentum | Athyriaceae | ||

| 54 | Athyrium filix-femina | Athyriaceae | Oxygen radical absorbance capacity | Soare et al., 2012a |

| 55 | Dryopteris affinis | Dryopteridaceae | ||

| 56 | Dryopteris filix-mas | Dryopteridaceae | ||

| 57 | Dryopteris cochleata | Dryopteridaceae | DPPH, ABTS•+, superoxide, nitric oxide, hydroxide, reducing power, ferrous chelating, and lipid peroxidation assays | Kathirvel et al., 2014 |

Fig. 2.

Color illustrations of medicinal pteridophytes: (a) P. aquilinum; (b) Lycopodium japonicum; (c) Marsilea quadrifolia; (d) Dicranopteris linearis; (e) Drynaria quercifolia; (f) Cibotium barometz; (g) Blechnum orientale; (h) Hemionitis arifolia

Note: for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article

According to Kshirsagar and Upadhyay (2009), methanol extracts of Diplazium polypodioides and ethyl acetate or water extracts of Blechnum orientale show strong antioxidant capacity (Lai et al., 2010). Lai and Lim (2011) reported that Pteris vittata, Cyathea latebrosa, Cibotium barometz (Fig. 2f), D. quercifolia, B. orientale (Fig. 2g), Adiantum radianum, Diplazium esculentum, Acrostichum aureum, Nephrolepis biserrata, and D. linearis exhibited strong antioxidant activity ranging from 0.12 to 0.57 mg/ml. The presence of phenolics in extracts of Dicksonia sellowiana may contribute directly to its antioxidant properties (Duh et al., 1999; Bora et al., 2005). Ethanolic and ethyl acetate extracts showed good antioxidant action based on the DPPH radical scavenging assay in Microgramma vacciniifolia (Peres et al., 2009). According to Hort et al. (2008), the antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective potential of crude extracts are based on organic solvents of increasing polarity. Gombau et al. (2006) demonstrated that hexane and chloroform extracts of P. leucotomos had significant inhibitory activity/strong antioxidative properties, based on an H2O2 (hydrogen peroxide) assay. The antioxidant properties of methanol extracts of rhizomes and fronds of D. mariesii, C. fortunei, D. crassirhizoma, D. nipponensis, P. lepidocaulon, P. polyblepharum, Dicranopteris pedata, Osmunda cinnamomea var. fokiensis (Fig. 3f), Osmunda japonica, A. pedatum, Pyrrosia lingua, L. japonicum (Fig. 2b), Thelypteris acuminata, Athyrium niponicum, Matteuccia struthiopteris (Fig. 3h), and Onoclea sensibilis var. interrupta were reported by Shin (2010) and Delong et al. (2011).

Fig. 3.

Color illustrations of medicinal pteridophytes: (a) Cyrtomium fortunei; (b) Adiantum capillus-veneris; (c) Cyathea gigantea; (d) Selaginella willdenowii; (e) Selaginella doederleinii; (f) Osmunda cinnamomea; (g) Pyrrosia lingua; (h) Matteuccia struthiopteris

Note: for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article

Methanol leaf extracts of P. multifida showed stronger antioxidant activity than ethanol extracts (Hoang and Tran, 2014). In a DPPH assay of S. palustris, antioxidant activity was higher in mature fertile (2.29 mg TE/mg GAE; TE: Trolox equivalent; GAE: gallic acid equivalent) and sterile (2.07 mg TE/mg GAE) fronds than in young fertile (1.99 mg TE/mg GAE) and sterile (1.80 mg TE/mg GAE) fronds. Moreover, significantly higher metal chelating activity was observed in young sterile fronds (101.22 µg EDTA/mg GAE; EDTA: ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) and mature fertile fronds (176.37 µg EDTA/mg GAE) than in young fertile fronds (82.14 µg EDTA/mg GAE) and mature sterile fronds (16.54 µg EDTA/mg GAE) (Chai et al., 2012). Methanol extracts from aerial plant parts of eleven different species of pteridophytes from Korea, namely A. pedatum, C. japonica, D. mariesii, C. fortunei, D. crassirhizoma, P. polyblepharum, P. lepidocolon, D. nipponensis, P. cretica, P. multifida, and P. nipponica displayed significant DPPH scavenging activity ranging from 0.05 to 1.66 mg/ml while the activity of rhizome extracts ranged only from 0.02 to 4.99 mg/ml. Using ABTS assays, Zakaria et al. (2011) found 0.06 to 0.53 mg/ml of activity in methanol extracts from aerial plant parts and 0.03 to 1.24 mg/ml in rhizome extracts. In DPPH assays, methanol extracts from leaves of D. linearis exhibited higher antioxidant activity (20 µg/ml) (37.8%) than aqueous (29.3%) or chloroform extracts (13.3%). In D. linearis, superoxide scavenging activity was the highest in methanol extracts (84.2%), moderate in aqueous extracts (62.1%), and the lowest in chloroform extracts (23.2%) (Milan et al., 2013). Methanol extracts of D. polypodiodes displayed only 5.87% antioxidant activity in DPPH assays (Kshirsagar and Upadhyay, 2009). The ethyl acetate, butanol, and water fractions of B. orientale revealed significant free radical scavenging activity (IC50 8.6–13.0 μg/ml) (Lai et al., 2010). Significant DPPH scavenging (0.12 to 0.14 mg/ml) and ferric reducing power (FRP) (963 to 1417 mg GAE/100 g) were observed in methanol extracts from leaves of C. latebrosa, Cibotium barometz, D. quercifolia, B. orientale, and D. linearis. Adiantum raddianum and P. vittata displayed the highest activity in DPPH scavenging (0.27 and 0.29 mg/ml, respectively) and FRP (842 and 578 mg GAE/100 g, respectively) (Lai and Lim, 2011).

3.2. Anti-cancer, antidiabetic, and antiviral activity

The anti-cancer activity of ferns is listed in Table 3, and their antidiabetic and antiviral activity in Table 4. Both ethanol and water extracts of Hemionitis arifolia (Burm.) Moore (Fig. 2h) showed hypoglycaemic and antidiabetic properties in rats (Ajikumaran Nair et al., 2006; Kumudhavalli and Jaykar, 2012). The antihyperglycemic and analgesic activity of the leaves of Christella dentata, Adiantum philippense, and Angiopteris evecta has been studied by Paul et al. (2012), Tanzin et al. (2013), and Sultana et al. (2014). Microsorum grossum has been used to cure liver cancer (Petard and Raau, 1972; Defilpps et al., 1988). Pteris polyphylla (Lee and Lin, 1988) and A. evecta (Defilpps et al., 1988) also show anti-cancer activity. In the Chinese traditional medicine system, “Gusuibu” has been used for its anti-cancer and anti-inflammation activity. It is prepared from the rhizomes of various ferns, namely D. fortunei (Kze.) J. Sm., P. coronans (Wall. Ex Mett.) Ching, D. divaricata BL., D. mariesii Moore ex-Bak, D. solida (Forst.) Sw., and H. griffithiana (Hk.) C. Chr. (Cui et al., 1990; Cai et al., 2004; ChPC, 2005; Chang et al., 2007a). M. quadrifolia has been used to treat human breast cancer, diabetes, and snake bites, and as an anti-inflammatory and diuretic (Uma and Pravin, 2013). The bear paw fern, Phlebodium decumanum has been used for anti-cancer, ulcer, and high blood pressure treatments (Punzon et al., 2003). The leaves and rhizomes of H. arifolia (Burm.) Moore and whole plants of Adiantum capillus-veneris L. were used by the tribes of the Valparai hills, Western Ghats, and Tamil Nadu (India) for their hypoglycaemic and anti-cancer activity (Santhosh et al., 2014). Both leaves and rhizomes of A. capillus-veneris L. have been used in the preparation of herbal drugs for treating diabetes in India and Europe. This fern has diverse phytochemical constituents: adiantone, adiantoxide, astragalin, β-sitosterol, caffeic acids, caffeylgalactose, caffeylglucose, campesterol, carotenes, coumaric acids, coumarylglucoses, diplopterol, epoxyfilicane, fernadiene, fernene, filicanes, hopanone, hydroxy-adiantone, hydroxy-cinnamic acid, isoadiantone, isoquercetin, kaempferols, lutein, mutatoxanthin, naringin, neoxanthin, nicotiflorin, oleananes, populnin, procyanidin, prodelphinidin, quercetins, querciturone, quinic acid, rhodoxanthin, rutin, shikimic acid, violaxanthin, and zeaxanthin (Taylor, 2003).

Table 3.

Anti-cancer property of pteridophytes

| No. | Plant name | Family name | Methods used | Source(s) |

| 1 | Microsorum grossum | Polypodiaceae | Traditional medicine | Petard and Raau, 1972; Defilpps et al., 1988 |

| 2 | Pteris polyphylla | Pteridaceae | In vitro antimutagenic activity, traditional Chinese medicine | Lee and Lin, 1988; Wang and Zhang, 2008 |

| 3 | Pteris multifida | Pteridaceae | In vitro MTT method; antimutagenic activity against picrolonic acid-induced mutation | |

| 4 | Angiopteris evecta | Marattiaceae | Traditional Chinese medicine | Defilpps et al., 1988 |

| 5 | Drynaria fortunei | Polypodiaceae | Traditional Chinese medicine | Punzon et al., 2003; Cai et al., 2004; ChPC, 2005; Chang et al., 2007a |

| 6 | Pseudodrynaria coronans | Polypodiaceae | Traditional Chinese medicine | |

| 7 | Phlebodium decumanum | Polypodiaceae | In vitro tumour necrosis inhibition | |

| 8 | Davallia mariesii | Davalliaceae | Korea folk medicine | Cui et al., 1990; Cai et al., 2004; ChPC, 2005 |

| 9 | Davallia divaricata | Davalliaceae | Traditional Chinese medicine | |

| 10 | Davallia solida | Davalliaceae | ||

| 11 | Humata griffithiana | Davalliaceae | ||

| 12 | Marsilea quadrifolia | Marsileaceae | In vitro cytotoxic activity on MCF-7 | Uma and Pravin, 2013 |

| 13 | Hemionitis arifolia | Pteridaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | Santhosh et al., 2014 |

| 14 | Adiantum capillus-veneris | Pteridaceae | ||

| 15 | Blechnum orientale | Blechnaceae | In vitro MTT assay against human colonic adenocarcinoma HT-29, human colonic carcinoma HCT-116, human breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7, human leukemia K562 | Lai and Lim, 2010 |

| 16 | Polypodium nipponica | Polypodiaceae | In vivo two-stage carcinogenesis test on mouse skin papillomas | Konoshima et al., 1996 |

| 17 | Polypodium formosanum | Polypodiaceae | ||

| 18 | Polypodium vulgare | Polypodiaceae | ||

| 19 | Polypodium fauriei | Polypodiaceae | ||

| 20 | Polypodium virginianum | Polypodiaceae | ||

| 21 | Dryopteris crassirizoma | Dryopteridaceae | ||

| 22 | Adiantum monochlamys | Pteridaceae | In vivo two-stage carcinogenesis test on mouse skin papillomas | |

| 23 | Oleandra wallichii | Oleandraceae | ||

| 24 | Cyrtomium fortunei | Dryopteridaceae | In vitro MTT assay on MGC-803, PC3, A375 tumor cells | Yang et al., 2013 |

| 25 | Asplenium polyodon | Aspleniaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | Singh, 1999; Santhosh et al., 2014 |

| 26 | Asplenium nidus | Aspleniaceae | ||

| 27 | Adiantum capillus-veneris | Pteridaceae | ||

| 28 | Ophioglossum gramineum | Ophioglossaceae | ||

| 29 | Hemionitis arifolia | Pteridaceae | ||

| 30 | Pteridium aquilinum | Dennstaedtiaceae | Anticancer compounds identified | Nwiloh et al., 2014 |

| 31 | Pityrogramma calomelanos | Pteridaceae | In vitro cytotoxicity against Dalton’s lymphoma ascites tumour cells and Ehrlich ascites tumour cells | Sukumaran and Kuttan, 1991; Shin, 2010; Zakaria et al., 2011; Milan et al., 2013 |

| 32 | Drynaria quercifolia | Polypodiaceae | Brine Shrimp lethality bioassay | |

| 33 | Dicranopteris linearis | Gleicheniaceae | In vitro MTT assay on MCT-7, HeLa, HT-29, HL-60, K-562, MDA-MB-231 | |

| 34 | Selaginella willdenowii | Selaginellaceae | In vitro cytotoxic activity on human cancer cell lines | Lee and Lin, 1988; Silva et al., 1995; Sun et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2000; Su et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2005b; Gao et al., 2007; Li J et al., 2014; Li S 2014; Elda et al., 2015 |

| 35 | Selaginella lepidophyla | Selaginellaceae | In vitro MTT assay on human colon cancer cell line (HTB-38) | |

| 36 | Selaginella labordei | Selaginellaceae | In vitro MTT assay on Bel-7402, HeLa, HT-29 | |

| 37 | Selaginella moellendorffii | Selaginellaceae | In vitro cytotoxic activity on human ovarian adenocarcinoma cells; in vitro MTT assay on cervical carcinoma (HeLa), foreskin fibroblast (FS-5), Bel-7402, HeLa, HT-29 | |

| 38 | Selaginella delicatula | Selaginellaceae | In vitro cytotoxic activity on Raji and Calu-1 tumor cell lines; in vitro MTT assay on Bel-7402, HeLa, HT-29 | |

| 39 | Selaginella tamariscina | Selaginellaceae | In vitro MTT assay; in vitro antiproliferative activity in leukemia cells, Bel-7402, HeLa, HT-29; in vivo single dose acute toxicity test | |

| 40 | Selaginella doederleinii | Selaginellaceae | Antimutagenic activity against picrolonic acid-induced mutation; in vitro antiproliferative against human cancer cells | |

| 41 | Selaginella uncinata | Selaginellaceae | In vitro MTT assay on Bel-7402, HeLa, HT-29 | |

| 42 | Selaginella remotifolia | Selaginellaceae | ||

| 43 | Selaginella pulvinata | Selaginellaceae | ||

| 44 | Adiantum venustum | Pteridaceae | Ehrlich ascites carcinoma in animal models, in vivo animal study | Woerdenbag et al., 1996; Li et al., 1998, 1999; Viral et al., 2011 |

| 45 | Pteris semipinnata | Pteridaceae | Human liver adenocarcinoma cell line (HePG II), human lung adenocarcinom a cell line (SPC-A-1), human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line (MGC-803), human nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells; in vitro MTT assay in HL-60 cells; in vivo anticancer activity | |

| 46 | Pteris multifida | Pteridaceae | In vitro MTT assay in Ehrlich ascites | |

| 47 | Pteris vittata | Pteridaceae | In vitro MTT assay on MCF-7 breast cancer cells | Chiu et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2013; Tomsik, 2013; Kaur et al., 2014; Xia et al., 2014 |

| 48 | Pteridium aquilinum | Dennstaedtiaceae | In vitro MTT assay | |

| 49 | Davallia cylindrica | Davalliaceae | In vitro MTT assay in A549 cells | |

| 50 | Stenoloma chusanum | Lindsaeaceae | ||

| 51 | Selaginella frondosa | Selaginellaceae | In vitro MTT assay in A549 cells | |

| 52 | Thelypteris torresiana | Thelypteridaceae | In vitro MTT assay in lung cancer cell line H1299 | |

| 53 | Selaginella ciliaris | Selaginellaceae | Potato disc-induced method | Sarker et al., 2011 |

| 54 | Marsilea minuta | Marsileaceae | ||

| 55 | Thelypteris prolifera | Thelypteridaceae | ||

| 56 | Trichomanes reniforme | Hymenophyllaceae | In vivo growth inhibitory activity against ascitic fibrosarcoma in Swiss mice;in vitro cytotoxicity | Guha et al., 1996 |

MTT: 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

Table 4.

Antidiabetic, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and wound healing activity of pteridophytes

| Medicinal use | No. | Plant name | Family name | Methods used | Source(s) |

| Antiviral activity | 1 | Hemionitis arifolia | Pteridaceae | In vivo glucose tolerance test and alloxan-induced diabetic rats; in vivo glucose tolerance test in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats; traditional Indian medicine | Ajikumaran Nair et al., 2006; Kumudhavalli and Jaykar, 2012; Santhosh et al., 2014 |

| 2 | Christella dentata | Thelypteridaceae | In vivo glucose tolerance test | Paul et al., 2012; Tanzin et al., 2013; Sultana et al., 2014 | |

| 3 | Adiantum philippense | Pteridaceae | In vivo study in alloxan-induced diabetic rats | ||

| 4 | Angiopteris evecta | Marattiaceae | In vivo glucose tolerance test | ||

| 5 | Adiantum capillus-veneris | Pteridaceae | Traditional Indian medicine; traditional medicine in Amazon; in vivo glucose tolerance test | Jain and Sharma, 1967; Taylor, 2003; Santhosh et al., 2014; Neef et al., 1995 | |

| 6 | Angiopteris evecta | Marattiaceae | In vivo glucose tolerance test | Miao et al., 1996; Nguyen, 2005 | |

| 7 | Selaginella tamarascina | Selaginellaceae | In vivo study in alloxan-induced diabetic rats | ||

| 8 | Asplenium polyodon | Aspleniaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | Singh, 1999; Chand Basha et al., 2013; Santhosh et al., 2014 | |

| 9 | Asplenium nidus | Aspleniaceae | |||

| 10 | Adiantum capillus-veneris | Pteridaceae | |||

| 11 | Ophioglossum gramineum | Ophioglossaceae | |||

| 12 | Hemionitis arifolia | Pteridaceae | |||

| 13 | Actiniopteris radiata | Pteridaceae | In vitro chromogenic DNSA method | ||

| 14 | Blechnum orientale | Blechnaceae | In vitro antiviral activity against hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and murine leukemia virus | Tsai and Hwang, 1999 | |

| 15 | Woodwardia orientalis | Blechnaceae | |||

| 16 | Woodwardia unigemmata | Blechnaceae | |||

| 17 | Athyrium acrostichoides | Athyriaceae | |||

| 18 | Sphaeropteris lepifera | Cyatheaceae | |||

| 19 | Cyrtomium fortunei | Dryopteridaceae | |||

| 20 | Dryopteris crassirhizoma | Dryopteridaceae | |||

| 21 | Osmunda japonica | Osmundaceae | |||

| 22 | Lygodium flexuosum | Lygodiaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | Dhiman, 1998 | |

| 23 | Lygodium japonicum | Lygodiaceae | In vitro antiviral activity against herpes simplex virus, Sindbis virus, and polio virus | Taylor et al., 1996 | |

| 24 | Asplenium adiantum-negrum | Aspleniaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | Vasudeva, 1999 | |

| 25 | Microsorum membranifolium | Polypodiaceae | Traditional Fijian medicine | Cambie and Ash, 1994 | |

| 26 | Pyrrosia lingua | Polypodiaceae | In vitro antiviral activity against Herpes simplex virus | Zheng, 1990 | |

| 27 | Trichomanes reniforme | Hymenophyllaceae | In vitro antiviral activity against HIV | Guha et al., 1996 | |

| 28 | Pteris glycyrrhiza | Pteridaceae | In vitro antiviral activity against bovine herpesvirus type | McCutcheon et al., 1995 | |

| 29 | Polypodium vulgare | Pteridaceae | Husson et al., 1986 | ||

| 30 | Polypodium aureum | Pteridaceae | |||

| Antiviral activity | 31 | Athyrium niponicum | Athyriaceae | In vitro antiviral activity | |

| 32 | Selaginella uncinata | Selaginellaceae | In vitro antiviral activity against respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza type 3 virus | ||

| Anti-inflammatory activity | 33 | Microsorum grossum | Polypodiaceae | Traditional herbal medicine | |

| 34 | Drynaria quercifolia | Polypodiaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | ||

| 35 | Microsorum scolopendria | Polypodiaceae | Traditional herbal medicine in Tonga | ||

| 36 | Polypodium leucotomos | Polypodiaceae | Traditional herbal medicine in Bolivia | ||

| 37 | Ophioglossum vulgatum | Ophioglossaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | ||

| 38 | Lygodium flexuosum | Lygodiaceae | |||

| 39 | Adiantum venustum | Pteridaceae | |||

| 40 | Adiantum caudatum | Pteridaceae | Traditional medicine in Malay Peninsula | ||

| 41 | Cheilanthes farinosa | Pteridaceae | In vivo anti-inflammatory activity | ||

| 42 | Pteris ensiformis | Pteridaceae | In vitro anti-inflammatory activity | ||

| 43 | Christella parasitica | Thelypteridaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | ||

| 44 | Huperzia serrata | Huperziaceae | Traditional Chinese medicine | ||

| 45 | Selaginella tamarascina | Selaginellaceae | In vitro anti-inflammatory activity | ||

| 46 | Selaginella bryopteris | Selaginellaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | ||

| 47 | Dryopteris sp | Dryopteridaceae | In vivo Carrageenan induced paw oedema method | ||

| 48 | Blechnum occidentale | Blechnaceae | |||

| 49 | Alsophila gigantea | Cyatheaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | ||

| 50 | Cyathea gigantea | Cyatheaceae | In vivo anti-inflammatory activity | ||

| 51 | Phlebodium decumanum | Polypodiaceae | In vitro anti-inflammatory activity | ||

| 52 | Phyllitis scolopendrium | Aspleniaceae | Traditional herbal medicine | ||

| 53 | Dicranopteris linearis | Gleicheniaceae | In vitro anti-inflammatory activity | ||

| Wound healing activity | 54 | Selaginella delicatula | Selaginellaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | |

| 55 | Dicranopteris linearis | Gleicheniaceae | |||

| 56 | Davallia solida | Davalliaceae | Traditional medicine in Hawaii | ||

| 57 | Polystichum pungens | Dryopteridaceae | Traditional medicine in South Africa | ||

| 58 | Angiopteris evecta | Marattiaceae | Traditional medicine in Fijian | ||

| 59 | Nephrolepis cordifolia | Nephrolepidaceae | Traditional Indian medicine | ||

| 60 | Ophioglossum reticulatum | Ophioglossaceae | |||

| 61 | Thelypteris arida | Thelypteridaceae | |||

| 62 | Phyllitis scolopendrium | Aspleniaceae | In vivo method | ||

| 63 | Pityrogramma calomelanos | Pteridaceae | Traditional medicine | ||

| 64 | Polypodium ssp. | Polypodiaceae | In vitro assay using platelet activating factor and leukotriene B(4) | ||

Pterosins, terpenoids, sterides, flavones, glucosides, aromatics, and pyrone compounds derived from C. barometz have antitumour properties (Wu et al., 2007; Xu et al., 2012). Plants in the polyploid genus Pteris contain many chemical compounds like apigenin-7-O-β-D-glucopyranosyl-4'-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside, luteolin-7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside, apigenin-7-O-β-D -glucopyranoside, apigenin, luteolin, naringenin-7-O-β-D-neohesperidoside, apigenin-7-O-β-D-neohespedoside, apigenin-4'-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside, (2S,3S)-pterosin C, isovanillic acid, ferulic acid, 2β,16α-dihydroxy-ent-kaurane 2-O-β-D-glucoside, 2β,6β,15α-trihydroxy-ent-kaur-16-ene, 9-hydroxy-15-oxo-ent-kaur-16-en-19-oic acid, 19β-D-glucoside, 2β,14β,15α,16α,17-pentahydroxy-ent-kaurane, and 9-hydroxy-ent-kaur-16-en-19-oic acid (Gong et al., 2007; Ouyang et al., 2008). Extracts of P. multifida have anti-cancer activity (Wang and Zhang, 2008). Ethyl acetate, butanol, and water extracts of B. orientale (Linn.) show notable anti-cancer properties (Lai et al., 2010). The antithiamin substances in brackens, such as astragalin, isoquercitrin, rutin, caffeic acid, and tannic acid have been identified as valuable natural constituents because of their antitumour or antioxidant properties (Kweon, 1986; Cai et al., 2004; Katsube et al., 2006). The ferns P. nipponica, Polypodium formosanum, Polypodium vulgare, Polypodium fauriei, Polypodium virginianum, Dryopteris crassirizoma, Adiantum monochlamys, and Oleandra wallichii have been shown to have anti-cancer activity (Konoshima et al., 1996). A. evecta and Selaginella tamariscina have been shown to have significant antidiabetic activity (Miao et al., 1996; Nguyen, 2005).

According to Singh (1999) and Lee et al. (2003), Asplenium polyodon, Asplenium nidus, A. capillus-veneris, Ophioglossum gramineum, and H. arifolia have anti-cancer, antidiabetic, and antiviral activity. Chloroform extracts of Actiniopteris radiata (Linn.) have significant antidiabetic activity as shown by the chromogenic DNSA (dinitrosalicylic) colorimetric method, and ethanolic extracts show strong in vitro antidiabetic properties when compared to n-hexane (Chand Basha et al., 2013). Both ethyl acetate and butanol extracts of the rhizome of C. fortunei (J.) Smith (Fig. 3a) exhibit anti-tumour activity (Yang et al., 2013). The phlorophenone derivatives in Dryopteris sp. (Kapadia et al., 1996) and A. capillus-veneris (Fig. 3b) that have anti-cancer activity have also been used as antidiabetic drugs in India and Europe (Jain and Sharma, 1967; Neef et al., 1995). β-Caryophyllene, linalool, geranial and γ-terpinene have also been isolated from the angiosperms Citrus and Croton flavens, revealing antitumour and antioxidant properties (Choi et al., 2000; Sylvestre et al., 2006). Moreover, anti-cancer compounds were detected in the essential oils of P. aquilinum L. Kuhn (Fig. 2a) (Nwiloh et al., 2014). Methanol extracts of Pityrogramma calomelanos, D. quercifolia, and D. linearis exhibit antitumour and cytotoxic activity (Sukumaran and Kuttan, 1991; Shin and Lee, 2010; Zakaria et al., 2011; Milan et al., 2013). Extracts of Adiantum venustum also have anti-cancer activity, as demonstrated by Viral et al. (2011). The lycophytes, Selaginella willdenowii (Fig. 3d), Selaginella lepidophyla, Selaginella labordei, Selaginella moellendorffii, Selaginella delicatula, S. tamariscina, and Sellaginella doederleinii (Fig. 3e) were shown to have cytotoxic and antimutagenic effects due to the presence of bioflavonoids (Lee and Lin, 1988; Silva et al., 1995; Sun et al., 1997; Lee et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2000; Su et al., 2000; Chen JJ et al., 2005; Gayathri et al., 2005; Woo et al., 2005; Gao et al., 2007; Shi et al., 2008; Tan et al., 2009), while Pteris semipinnata (Fig. 4c) and P. multifida have cytotoxic effects due to the presence of diterpenes (Woerdenbag et al., 1996; Li et al., 1998, 1999). Several authors have studied the anti-cancer potentials of ferns and lycopods, namely P. aquilinum, Davallia cylindrical, Stenoloma chusanum, Selaginella frondosa, Thelypteris torresiana, P. vittata, Selaginella ciliaris, Marsilea minuta, and Thelypteris prolifera (Chiu et al., 2009; Sarker et al., 2011; Tomsik, 2013; Zhang et al., 2013; Kaur et al., 2014; Xia et al., 2014).

Fig. 4.

Color illustrations of medicinal pteridophytes: (a) Equisetum ramosissimum; (b) Asplenium bulbiferum; (c) Pteris semipinnata; (d) Woodwardia orientalis; (e) Lygodium flexuosum; (f) Pteris ensiformis

Note: for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article

According to Tsai and Hwang (1999), the hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a prominent infectious disease agent worldwide, especially in Asia and Africa, causing liver cirrhosis and cancer. Blechni rhizome, known for its antiviral (HBV) activity, is prepared from the roots and stems of various ferns including B. orientale, D. crassirhizoma, O. japonica, Woodwardia orientalis (Fig. 4d), Woodwardia unigemmata (Fig. 5b), Athyrium acrostichoides, Sphaeropteris lepifera, and C. fortunei. Likewise, an herbal mixture of Woodwardia species with some other flowering plants has shown anti-HIV-1 (human immunodeficiency virus) activity. Lygodium flexuosum (Dhiman, 1998) and Asplenium adiantum-nigrum (Vasudeva, 1999) have shown significant effects against viral disease and jaundice, while Microsorum membranifolium has shown activity against children’s influenza (Cambie and Ash, 1994). The antiviral and anti-tumor activity shown by Trichomanes reniforme is due to the presence of mangiferin, which can kill cancer cells and has anti-HIV effects (Guha et al., 1996). The antiviral activity of Pteris glycyrrhiza (McCutcheon et al., 1995), P. vulgare, and Polypodium aureum (Husson et al., 1986) has been documented. A new antiviral compound, woodorien, was derived and identified by Xu et al. (1993). A. niponicum is reported to have anti-HIV properties (Mizushina et al., 1998), while Taylor et al. (1996) have shown that L. japonicum has antiviral effects against the Sindbis virus. Zheng (1990) revealed the antiviral activity of P. lingua (Fig. 3g) against the herpes simplex virus. Selaginella uncinata (Fig. 5c) displays antiviral activity against the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and parainfluenza type 3 virus (PIV3) (Ma et al., 2003).

Fig. 5.

Color illustrations of medicinal pteridophytes: (a) Selaginella delicatula; (b) Woodwardia unigemmata; (c) Selaginella uncinata; (d) Huperzia serrata; (e) Nephrolepis cordifolia; (f) Pittyrogramma calomelanos; (g) Selaginella involvens; (h) Psilotum nudum

Note: for interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article

3.3. Anti-inflammatory activity

In general, free radicals participate in numerous natural processes that are harmful to lipids, proteins, membranes, and nucleic acids, thereby contributing to a variety of diseases (Hadi et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2005; Campos et al., 2006). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) contribute to both normal cell function and pathological ailments such as atherosclerosis, inflammatory injury, cancer, and cardiovascular disease. Inflammation is a typical defensive response to cellular damage produced by physical distress (cuts, burns, or bruises), toxic chemicals, microbial agents, or autoimmune disease. Unfortunately, drugs currently available to treat pain and inflammation have numerous harmful side effects and low efficiency. Natural products are often easily available, with high clinical effectiveness and few side effects. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 80% of the global population still depends on ethnomedicinal practices for treating their illnesses (Gurib-Fakim, 2006).

In inflammatory disorders, extreme stimulation of phagocytes and the production of O2− (oxygen radicals), OH− (hydroxide ions), and H2O2 (Gillham et al., 1997) are severely harmful to tissues, by their significant direct or indirect oxidizing action. Hydrogen peroxide and OH– radicals formed from O2− cause lipid peroxidation resulting in membrane destruction. In addition, tissue damage provokes an inflammatory response involving the production of mediators and chemotactic factors (Lewis, 1989). The free radical scavenging activity of plant products is primarily due to various bioactive compounds like phenolics, flavonoids, phenolic diterpenes, and tannins (Lee et al., 2004). Currently, steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) used to treat inflammatory disease frequently produce severely harmful effects (Vonkeman and van de Laar, 2010; Vijayalakshmi et al., 2011). Thus, there is abundant motivation to find new drugs with anti-inflammatory properties and fewer side effects, especially from plants used in folk medicine. Moreover, plant-derived natural products such as alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, and terpenes have attracted significant attention recently due to their varied medicinal actions, including anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antioxidant properties (Pandurangan et al., 2008). Traditional healers have defined the healing efficiencies of native medicinal plants for various diseases. Because bioproducts are a source of synthetic and traditional herbal medicines, which can potentially be used by modern health care systems, scientists have been urged to study these plants to identify their medicinal properties (Vimala et al., 2012).

Pteridophytes (the ferns and their allies) have an extensive geologic history as pioneer plants that have occupied various parts of our globe for millions of years. This group comprises a huge group of seedless vascular plants and occupies a significant place in primary health care because of their cost effectiveness. Economic crises in developing countries mean that different fern species are presently used for various ailments (Ho et al., 2011). On the basis of antioxidant activity, ferns exhibit bioactivity such as anti-microbial, anti-viral, anti-inflammatory, anti-tussive, and anti-tumor activity (Chang et al., 2011). The Malasar tribes in the Valparai hills (Western Ghats, India) use both S. delicatula (Fig. 5a) and D. linearis for their wound healing activity (Santhosh et al., 2014). Table 4 shows the anti-inflammatory and wound healing activity of pteridophytes. In many studies, anti-inflammatory activity has been reported for many species of medicinal ferns, including M. grossum (Petard and Raau, 1972; Whistler, 1992), D. quercifolia (Dixit and Vohra, 1984), A. aureum (Defilpps et al., 1988), Selaginella bryopteris (Dhiman, 1998), Ophioglossum vulgatum, L. flexuosum, A. venustum (Vasudeva, 1999), Adiantum caudatum (Burkill, 1996), Christella parasitica (Gogoi, 2002), Huperzia serrata (Fig. 5d) (Zangara, 2003), S. tamariscina (Woo et al., 2005), P. ensiformis (Fig. 4f) (Wu et al., 2005), P. multifida (Lee and Lin, 1988), Dryopteris sp. (Otsuka et al., 1972), Cheilanthes farinosa (Yonathan et al., 2006), Cyathea gigantea (Fig. 3c) (Benjamin and Manickam, 2007; Madhukiran and Ganga Rao, 2011), Blechnum occidentale (Nonato et al., 2009), D. mariesii (Chang et al., 2007b), Microsorum scolopendria (Bloomfield, 2002), Phyllitis scolopendrium (Bonet and Valles, 2007), and P. leucotomos (Lucca, 1992). In addition, wound healing activity has been reported for many species of ferns such as D. solida (Whistler, 1992), Polystichum pungens (Grierson and Afolayan, 1999), A. evecta (Cambie and Ash, 1994), Nephrolepis cordifolia (Fig. 5e), Ophioglossum reticulatum, Thelypteris arida (Upreti et al., 2009), P. scolopendrium (Oniga et al., 2004), P. calomelanos (Fig. 5f) (de Feo, 2003), Polypodium spp. (Liu et al., 1998), and P. decumanum (Punzon et al., 2003).

3.4. Antimicrobial activity

There are many antibiotics currently available for the treatment of infection, including chloramphenicol, tetracycline, erythromycin, penicillin G, ampicillin, cephalosporin, ciprofloxacin, kanamycin, gentamicin, neomycin, amoxycillin, nystatin, amphotericin-B, and ketaconazole (Kaufman, 2000). Although there are numerous antibiotics for healing bacterial and fungal infection, they are not always reliable against pathogenic organisms (Gearhart, 1994). Their use is restricted by several factors such as low potency, poor solubility, and drug toxicity (Fromtling and Rahway, 1987; Portillo et al., 2001). The development of resistance in pathogenic bacteria and fungi against most of the conventionally available drugs has been reported (Cuenca-Estrella et al., 2000). Confounding the issue further is the indiscriminate use of antibiotics, which leads to the loss of their effectiveness. Many of the pathogens, especially bacteria and fungi, have developed substantial resistance to the antibiotics (Darokar et al., 1998; Jones, 1998; Austin et al., 1999). Moreover, the widespread use of antibiotics has led to the decimation of sensitive organisms from the population with the consequence that there has been an increase in the number of resistant microorganisms. This situation has forced scientists to search for new bioactive compounds in traditional complementary medicines derived from plants (Kumar et al., 2006). Plant extracts have been widely used since ancient times for treating human illnesses. Numerous studies of the antimicrobial activity of different natural products have been reported (Bhattacharjee et al., 2006; Parekh and Chanda, 2006, 2007; Vaghasiya et al., 2008). Although the medicinal value of pteridophytes has been known to traditional cultures for more than 2000 years, they are used only on a small scale in modern chemotherapy. Studies of the bioactivity of pteridophytes are still in their early years compared with those of angiosperms.

The Greek botanist Theophrastus (ca. 372–287 BC) wrote about the medicinal value of pteridophytes. Dioscorides (ca. 50 AD) in his de Materia Medica also referred to a number of ferns, including P. aquilinum and Dryopteris filix-mas, as having medicinal values. In ancient Indian medicine systems, several ferns were used to cure a number of human ailments. Sushruta (ca. 100 AD) and Charaka (ca. 100 AD) recommended the medicinal use of some ferns in their samhitas. Several ferns have been used by Unani physicians in India and Western Asia (Banerjee and Sen, 1980). The antimicrobial activity of pteridophytes is summarized in Table 5. Several studies have been carried out to explore the antimicrobial activity of ferns such as Nephrolepis acuminata (Jimenez et al., 1979), Davallia sodila, Lygodium reticulatum (Cambie and Ash, 1994), Marattia fraxinea (de Boer et al., 2005), Sphenomeris chinensis (Sengupta et al., 2002), A. caudatum, Adiantum peruvianum, A. venustum, Adiantum incisum, Adiantum latifolium, and Ampelopteris prolifera (Banerjee and Sen, 1980; Lakshmi et al., 2006; Lakshmi and Pullaiah, 2006; Singh et al., 2008a), P. aquilinum (Francisco and Driver, 1984), Nephrolepis sp. (Basile et al., 1997), Adiantum lunulatum (Reddy et al., 2001), E. arvense (Joksic et al., 2003; Radulovic et al., 2006), S. tamariscina (Woo et al., 2005), A. capillus-veneris (Guha et al., 2004, 2005; Besharat et al., 2008), Athyrium pectinatum (Parihar et al., 2006), P. vittata (Singh et al., 2008b), P. multifida (Hu et al., 2008; Hum et al., 2008), Mecodium exsertum (Maridass, 2009), Selaginella involvens (Fig. 5g), S. inaequalifolia (Haripriya et al., 2010), S. pallescens (Rojas et al., 1999), Asplenium scolopendrium, Cystopteris fragilis, P. vulgare (Soare et al., 2012b), A. caudatum, A. evecta, Pteris confusa, P. argyraea, Lygodium microphyllum (Gracelin et al., 2012), Pteris biaurita (Dalli et al., 2007; de Britto et al., 2012), D. crassirhizoma (Lee et al., 2009), and various species (Maruzzella, 1961; McCutcheon et al., 1995). Furthermore, several studies (May, 1978; Dixit and Vohra, 1984; Dixit, 1992; Verma and Singh, 1995; Manandhar, 1996; Das, 1997; Singh, 1999; Benjamin and Manickam, 2007) have reported the antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal activity of Equisetum ramosissimum (Fig. 4a), A. aureum, D. quercifolia, Psilotum nudum (Fig. 5h), Parahemionitis arifolia, Helminthostachys zeylanica, O. gramineum, Tectaria caodunata, S. involvens, S. delicatula, Hypodematium crenatum, Leucostegia immersa, and Solvinia molusta. Singh (1999) documented antibacterial and antifungal activity of Botrychum lanuginosum, Dryopteris cochleata, N. cordifolia, Polystichum molluscens, Polystichum squarrosum, Salvinia radicata, Sphaerostephanos unitus, S. palustris, P. cretica, and P. vittata. Although several studies have reported the antimicrobial activity of ferns, in-depth studies to estimate minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC) have not yet been carried out for several ferns.

Table 5.

Antimicrobial activity of pteridophytes

| No. | Plant name | Family name | Methods used | Source(s) |

| 1 | Nephrolepis acuminata | Nephrolepidaceae | In vitro bioassay | Jimenez et al., 1979 |

| 2 | Davallia sodila | Davalliaceae | Traditional Fijian medicine | Cambie and Ash, 1994 |

| 3 | Lygodium reticulatum | Lygodiaceae | ||

| 4 | Marattia fraxinea | Marattiaceae | In vitro antimicrobial assay | de Boer et al., 2005 |

| 5 | Sphenomeris chinensis | Lindsaeaceae | Sengupta et al., 2002 | |

| 6 | Adiantum caudatum | Pteridaceae | Banerjee and Sen, 1980; Lakshmi and Pullaiah, 2006; Lakshmi et al., 2006; Singh et al., 2008a | |

| 7 | Adiantum peruvianum | Pteridaceae | ||

| 8 | Adiantum venustum | Pteridaceae | ||

| 9 | Adiantum incisum | Pteridaceae | ||

| 10 | Adiantum latifolium | Pteridaceae | ||

| 11 | Ampelopteris prolifera | Thelypteridaceae | ||

| 12 | Pteridium aquilinum | Dennstaedtiaceae | Francisco and Driver, 1984 | |

| 13 | Nephrolepis sp. | Nephrolepidaceae | Basile et al., 1997 | |

| 14 | Equisetum arvense | Equisetaceae | Joksic et al., 2003; Radulovic et al., 2006 | |

| 15 | Athyrium pectinatum | Athyriaceae | Parihar et al., 2006 | |

| 16 | Adiantum lunulatum | Pteridaceae | Reddy et al., 2001 | |

| 17 | Adiantum capillus-veneris | Pteridaceae | Guha et al., 2004, 2005; Besharat et al., 2008 | |

| 18 | Pteris vittata | Pteridaceae | Singh et al., 2008b | |

| 19 | Pteris multifida | Pteridaceae | Hu et al., 2008; Hum et al., 2008 | |

| 20 | Microsorum grossum | Polypodiaceae | Traditional Polynesian medicine | Whistler, 1992 |

| 21 | Mecodium exsertum | Hymenophyllaceae | In vitro antimicrobial assay | Maridass, 2009 |

| 22 | Selaginella involvens | Selginellaceae | Rojas et al., 1999; Haripriya et al., 2010 | |

| 23 | Selaginella inaequalifolia | Selginellaceae | ||

| 24 | Selaginella pallescens | Selginellaceae | ||

| 25 | Asplenium scolopendrium | Aspleniaceae | Soare et al., 2012b | |

| 26 | Cystopteris fragilis | Cystopteridaceae | ||

| 27 | Polypodium vulgare | Polypodiaceae | ||

| 28 | Angiopteris evecta | Marattiaceae | Gracelin et al., 2012 | |

| 29 | Adiantum caudatum | Pteridaceae | ||

| 30 | Pteris confusa | Pteridaceae | ||

| 31 | Pteris argyraea | Pteridaceae | ||

| 32 | Lygodium microphyllum | Lygodiaceae | ||

| 33 | Pteris biaurita | Pteridaceae | Dalli et al., 2007; de Britto et al., 2012 | |

| 34 | Dryopteris crassirizoma | Dryopteridaceae | Lee et al., 2009 | |

| 35 | Equisetum ramosissimum | Equisetaceae | Traditional Indian medicines | May, 1978; Dixit and Vohra, 1984; Dixit, 1992; Verma and Singh, 1995; Manandhar, 1996; Das, 1997; Singh, 1999; Benjamin and Manickam, 2007 |

| 36 | Drynaria quercifolia | Polypodiaceae | ||

| 37 | Psilotum nidum | Psilotaceae | ||

| 38 | Parahemionitis arifolia | Pteridaceae | ||

| 39 | Acrostichum aureum | Pteridaceae | ||

| 40 | Helminthostachys zeylanica | Ophioglossaceae | ||

| 41 | Ophioglossum gramineum | Ophioglossaceae | ||

| 42 | Tectaria caodunata | Tectariaceae | ||

| 43 | Selaginella involvens | Selaginellaceae | ||

| 44 | Selaginella delicatula | Selaginellaceae | ||

| 45 | Hypodematium crenatum | Woodsiaceae | ||

| 46 | Leucostegia immersa | Davalliaceae | ||

| 47 | Solvinia molusta | Salviniaceae | ||

| 48 | Marsilea quadrifolia | Marsileaceae | Brine shrimp lethality bioassay | Ripa et al., 2009 |

3.5. Activity against Alzheimer’s disease and brain illness

Frequently, alkaloids act as stimulators of the nervous system, and occasionally as toxins. Cocaine (has an anaesthetic effect), atropine (affects motor nerves), and curare (used by South American natives to cause paralysis of prey), are all alkaloids (Kretovich, 1966). Even though several alkaloids are present in angiosperms, some specific groups of alkaloids, namely lycopodine and huperzine, are synthesized by the lower groups of plants, like club mosses. Some lycopodium alkaloids naturally present in Lycopodium sp. and other pteridophytes have some pharmacological activity. α-Onocerin and lycoperine A show acetylcholinesterase inhibition activity (Zhang et al., 2002; Hirasawa et al., 2006). Huperzine A obtained from Huperzia species and other members of the Lycopodiaceae, has been shown to improve memory in animals. Huperzia quadrifariata and Huperzia reflexa were also found to cure Alzheimer’s disease (Ma and Gang, 2004; Ma et al., 2007; Singh and Singh, 2010; Konrath et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2012). Amentoflavone and ginkgetin, flavonoids found in Selaginella, display neurodefensive activity against cytotoxic stress, which suggests their promising usage to cure neurodegenerative diseases such as stroke and Alzheimer’s (Kang et al., 2004). The neuromodulatory tendency of S. delicatula using in vivo models of chemically induced neurodegenerative diseases has been studied in rodent systems and Drosophila. Extracts of S. delicatula showed neuroprotective efficacy against Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, reduced glutathione levels, and acetyl cholinesterase inhibitory activity (Chandran and Muralidhara, 2014). The pteridophyte Drynaria is also used in traditional medicine in China to treat Alzheimer’s disease. According to Yang (2005), 120 g of Drynaria (in decoction) produced significant improvement in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Likewise, Nephrolepis auriculata, S. bryopteris, H. zeylanica, and Lycopodium were used to treat brain fever, headache, and unconsciousness, to improve vitality, and as a brain tonic and memory enhancer (Bai, 1993; Samant et al., 1998; Vasudeva, 1999; Kholia and Punetha, 2005).

4. Traditional uses of some pteridophytes

In India, the Gond communities of Badkachhar, Bariaam and Dapka ingest the juice of whole fresh plants to cure cough and diabetes mellitus. Leaves of A. philippense are used to cure fever, cough, asthma, leprosy, and hair loss, while whole plants of B. orientale are used in anathematic and typhoid treatments. Fronds of B. orientale ground in cow’s milk are used in the treatment of asthma, as antibacterials and anthelmintics, and to improve fertility in women. The whole plant of H. zeylanica is considered an intoxicant, anodyne, and is also used as an aphrodisiac. L. flexuosum (Fig. 4e) is used to cure skin diseases, rheumatism, sprains, scabies, eczema, cut wounds, and rheumatism, and as an expectorant. A paste made from the leaves of N. cordifolia is applied to wounds to stop bleeding. Whole plants of S. bryopteris are used as diuretics, and to treat gonorrhoea (Singh and Upadhyay, 2012). A. capillus-veneris is used for antifungal growth and to remove dandruff, and the juice of leaves is drunk to protect against infertility. In addition, A. caudatum is used to cure jaundice, scabies, abdominal pain, and constipation. The young fronds of A. incisum are used to treat malaria and bronchial diseases, while leaves and rhizomes of A. venustum are thought to cure diabetes, and are used to treat liver problems and circulatory disorders. Leaves of Asplenium bulbiferum (Fig. 4b) are applied externally to hemorrhoids, and fronds are taken for liver problems. Decoctions from the rhizomes of P. aquilinum are drunk as a herbal health tea, and the rhizomes of W. unigemmata are used to cure skin diseases. Leaf juices are used as a tea or bath for curing infertility in women, for abdominal pain, constipation and sore throats (Nwosu, 2002). A paste of leaves and rhizomes mixed with lukewarm milk for 30 d is used as an effective tonic. A paste of P. vittata was applied twice to glandular swellings for 15 d (Sharma, 2002). M. grossum is commonly used in Tahiti (Whistler, 1992), H. serrata in China (Zangara, 2003), and S. bryopteris in India (Dhiman, 1998) for their anti-inflammatory activity. A decoction of roots and fronds of D. quercifolia is used as a tonic for the bowels, and aqueous extracts of the rhizomes are applied to wounds and cuts (Anonymous, 1952, 1986; Singh, 1973; Islam, 1983; Jain, 1991). Dried rhizomes of P. aquilinum mixed with milk are used to relieve diabetic disorders, and tender fronds are used as vegetables. Green fronds are used as fodder, make a good soil binder, and are also used in the preparation of manure (Anonymous, 1972, 1986; Islam, 1983; Jain, 1991). A paste made from the rhizomes of O. vulgatum has been externally applied to wounds, dropped in sore eyes as a detergent, and made into an antiseptic. Infusions can be taken internally for vulnerary or to treat bleeding of the nose or mouth, and a decoction has been drunk to treat heart troubles (Anonymous, 1966, 1986; Islam, 1983). In Malaya, a rhizome paste of A. aureum is applied to wounds and boils, and in the Philippines, leaves of A. caudatum are used externally as remedies for skin disease and internally for diabetes. Rhizomes of C. barometz in the Philippines are used to treat wounds and ulcers. Roots and leaves of Lygodium circinnatum are applied to wounds in the Dutch East Indies (Quisumbing, 1951). Tribal people of the Palani hills from South India use A. incisum, C. gigantea, and C. nilgirensis to treat diabetes, while N. cordifolia, H. arifolia, and Microsorum punctatum are applied to cuts and wounds, or used as anti-inflammatories (Sathiyaraj et al., 2015). In the Similipal Biosphere Reserve of Orissa (India), A. evecta, A. caudatum, B. orientale, Ceratopteris thalictroides, M. punctatum, P. biaurita, and P. cretica are used to cure cuts, wounds, and inflammation (Rout et al., 2009).

5. Mechanisms of action of phytochemicals

In this review we have documented most of the pteridophytes evaluated for phytochemical composition and bioactivity. Tables 1–5 summarize the presence of phytochemicals and their medicinal uses in pteridophytes. Although there are more than 12 000 species of pteridophytes distributed all over the world, few have been evaluated for their phytochemicals and their pharmacological properties. Most studies have reported only in vitro bioactivity, which suggests to investigate the pteridophytes could exert in vivo bioactivity. In general, phenolic compounds exist in both edible and non-edible plants and have proven bioactive. Phenolics are present in diverse groups of plants and show antimutagenic, anti-cancer, and antioxidant activity, which is beneficial to human life (Li et al., 2006). Due to synergistic effects, mixtures of bioactive compounds such as phenols, flavonoids, tannins, catechins, vitamins C and E, and β-carotene may give better protection/bioactivity than single phytochemicals (Bazzano et al., 2003). Phenolic compounds have been shown to have significant antioxidant effects (Newell et al., 2010). Phenols, flavonoids, anthocyanins, and phenolic acids have been obtained from plants to attain an idyllic structural chemistry for scavenging free radicals. The antioxidant potential of polyphenols may arise from their great reactivity as hydrogen or electron donors. The polyphenol-derived radical stabilize and delocalize the unpaired electron (Chanda and Dave, 2009). The scavenging of DPPH and ABTS radicals may be associated with the hydroxyl groups in caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid. The radical scavenging activity of phenolic compounds is influenced by the number of hydroxyl groups on the aromatic ring (Lazarova et al., 2014). Both rutin and quercetin significantly chelate metal ions and have ferric reducing antioxidant power (Azuma et al., 1999). According to Kim et al. (2004), rutin and quercetin express their anti-inflammatory activity through modulation of the expression of pro-inflammatory genes such as cyclooxygenase-2 and inducible nitric oxide synthase, and via some vital cytokines. Based on these distinctive mechanisms, flavonoids are considered as plausible substances for anti-inflammatory activity. The presence of caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid, rutin, and quercetin has been reported in many pteridophytes, namely P. multifida, P. vittata, P. aquilinum, P. leucotomos, Cyathea phalerata, S. tamariscina, O. sensibilis, M. struthiopteris, D. linearis, P. nudum, E. arvense, and A. capillus-veneris (Table 1).

Free radicals are generated in cells where they accumulate and react with macromolecules, like lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, thereby disrupting cellular functions. In addition, oxidative damage to cellular components results in alteration of membrane properties such as fluidity, ion transport, enzyme activity, and protein cross-linking, causing cell death (Chauhan and Chauhan, 2006). Bio-compounds containing antioxidant potential have the capacity to inhibit carcinogenesis (Wang et al., 2011; Firdaus et al., 2013). In earlier studies, apigenin, quercetin, and luteolin were shown to inhibit cancer cell proliferation (Mishra et al., 2013a, 2013b; Fotsis et al., 1997). Moreover, phenolics have been observed to postpone or inhibit the progression of various diseases by preventing peroxidation of lipid membranes (Kumar et al., 2013a, 2013b). Some bioactivity, such as lipoprotective, antiplatelet, and anti-inflammatory activity, is closely associated with antioxidative flavonoids (Kumar et al., 2012). Flavonoids have the potential to be reducing agents and to scavenge free radicals, chelate metal ions and inhibit enzymatic systems (topoisomerases and kinases) responsible for free radical generation (Kumar and Pandey, 2013). Yang et al. (2013) reported the inhibition of cancer cell lines, such as stomach cancer, prostate cancer, malignant melanoma, and mouse fibroblasts, by crude extracts and several isolated compounds (Table 1) of C. fortunei. In addition, apigenin was found to induce apoptosis and suppress insulin-like growth factor I receptor signalling in human prostate cancer (Way et al., 2004; Shukla and Gupta, 2009). Some flavonoids, such as quercetin, apigenin, kaempferol, and rutin in Murraya koenigii, inhibit endogenous 26S proteasome activity in MDA-MB-231 cells (Noolu et al., 2016). Several authors have reported the presence of apigenin, kaempferol, and luteolin in following species, namely P. multifida, P. aquilinum, Selaginella sp., A. capillus-veneris, C. phalerata, P. vittata, O. sensibilis, M. struthiopteris, Equisetum ramoissimum, S. doederleinii, D. linearis, P. nudum, Pityrogramma tartarea, P. calomelanos, Cheilanthes concolor, Cardamine flexuosa, Cardamine goyazensis, Pellaea cymbiformis, P. gleichenioides, P. pinnata, P. riedelii, Pteris altissima, Pteris angustata, Pteris decurrens, Pteris deflexa, Pteris denticulata, Pteris plumula, Pteris podophylla, Pteris splendens, Pteris propinqua, and C. fortunei (Table 1). Synergism between several flavones and flavonols for antimicrobial activity was confirmed in an earlier study. Moreover, quercetin and naringenin were found to significantly inhibit bactericidal motility (Yilmaz and Toledo, 2004). The release of ROS from activated neutrophils and macrophages causes inflammation injury. Excessive production may lead to tissue injury by damaging macromolecules and lipid peroxidation of membranes (Winrow et al., 1993; Gutteridge, 1995). ROS inflammation stimulates the release of cytokines, such as interleukin-1, tumour necrosis factor-α, and interferon-α, which stimulate the production of extra neutrophils and macrophages. However, free radicals are the main mediators promoting the inflammatory process. By neutralizing free radicals, antioxidants can reduce inflammation (Delaporte et al., 2002; Geronikaki and Gavalas, 2006). Therefore, we urge biologists to focus on the mechanisms of action of bioactive compounds from early tracheophytes (pteridophytes) in medicinal applications.

6. Conclusions

Several researchers have studied the phytochemical and medicinal uses of lycophytes and ferns in recent years. These studies have demonstrated the importance of ferns and their allies in plant science fields. We have listed here the medicinal uses of pteridophytes, specifically their antioxidant, antidiabetic, anti-cancer, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, wound healing, antimicrobial, and anti-Alzheimer activity. No significant review papers on medicinal pteridophytes have been published recently, only a few articles with inadequate reports. The medicinal pteridophytes listed in this review belong to the following thirty families: Davalliaceae, Equisetaceae, Lygodiaceae, Ophioglossaceae, Polypodiaceae, Psilotaceae, Pteridaceae, Salviniaceae, Selaginellaceae, Tectariaceae, Woodsiaceae, Aspleniaceae, Athyriaceae, Blechnaceae, Cyatheaceae, Dennstaedtiaceae, Dicksoniaceae, Dryopteridaceae, Hymenophyllaceae, Lindsaeaceae, Thelypteridaceae, Marsileaceae, Nephrolepidaceae, Onocleaceae, Marattiaceae, Oleandraceae, Osmundaceae, Cystopteridaceae, Gleicheniaceae, and Huperziaceae. Our review might encourage an appreciation of the uses of pteridophytes beyond ornamental purposes and, in particular, promote their use and development for medicinal benefits.

7. Future directions