Key Points

Question

Is sodium oxybate superior to placebo in improving electrophysiologic measures of daytime sleepiness and sleep disturbance in Parkinson disease?

Findings

In this double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial including 12 patients with Parkinson disease, sodium oxybate, compared with placebo, significantly improved sleepiness and disturbed nighttime sleep both subjectively and objectively. However, it induced de novo obstructive sleep apnea in 2 patients and parasomnia in 1 patient.

Meaning

The study provides class I evidence for the efficacy of sodium oxybate for sleep-wake disturbances in patients with Parkinson disease, but stringent monitoring is necessary and larger follow-up trials with longer treatment durations are warranted for validation.

Abstract

Importance

Sleep-wake disorders are a common and debilitating nonmotor manifestation of Parkinson disease (PD), but treatment options are scarce.

Objective

To determine whether nocturnal administration of sodium oxybate, a first-line treatment in narcolepsy, is effective and safe for excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and disturbed nighttime sleep in patients with PD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover phase 2a study carried out between January 9, 2015, and February 24, 2017. In a single-center study in the sleep laboratory at the University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 18 patients with PD and EDS (Epworth Sleepiness Scale [ESS] score >10) were screened in the sleep laboratory. Five patients were excluded owing to the polysomnographic diagnosis of sleep apnea and 1 patient withdrew consent. Thus, 12 patients were randomized to a treatment sequence (sodium oxybate followed by placebo or placebo followed by sodium oxybate, ratio 1:1) and, after dropout of 1 patient owing to an unrelated adverse event during the washout period, 11 patients completed the study. Two patients developed obstructive sleep apnea during sodium oxybate treatment (1 was the dropout) and were excluded from the per-protocol analysis (n = 10) but included in the intention-to-treat analysis (n = 12).

Interventions

Nocturnal sodium oxybate and placebo taken at bedtime and 2.5 to 4.0 hours later with an individually titrated dose between 3.0 and 9.0 g per night for 6 weeks with a 2- to 4-week washout period interposed.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome measure was change of objective EDS as electrophysiologically measured by mean sleep latency in the Multiple Sleep Latency Test. Secondary outcome measures included change of subjective EDS (ESS), sleep quality (Parkinson Disease Sleep Scale–2), and objective variables of nighttime sleep (polysomnography).

Results

Among 12 patients in the intention-to-treat population (10 men, 2 women; mean [SD] age, 62 [11.1] years; disease duration, 8.4 [4.6] years), sodium oxybate substantially improved EDS as measured objectively (mean sleep latency, +2.9 minutes; 95% CI, 2.1 to 3.8 minutes; P = .002) and subjectively (ESS score, −4.2 points ; 95% CI, −5.3 to −3.0 points; P = .001). Thereby, 8 (67%) patients exhibited an electrophysiologically defined positive treatment response. Moreover, sodium oxybate significantly enhanced subjective sleep quality and objectively measured slow-wave sleep duration (+72.7 minutes; 95% CI, 55.7 to 89.7 minutes; P < .001). Differences were more pronounced in the per-protocol analysis. Sodium oxybate was generally well tolerated under dose adjustments (no treatment-related dropouts), but it induced de novo obstructive sleep apnea in 2 patients and parasomnia in 1 patient, as detected by polysomnography, all of whom did not benefit from sodium oxybate treatment.

Conclusions and Relevance

This study provides class I evidence for the efficacy of sodium oxybate in treating EDS and nocturnal sleep disturbance in patients with PD. Special monitoring with follow-up polysomnography is necessary to rule out treatment-related complications and larger follow-up trials with longer treatment durations are warranted for validation.

Trial Registration

clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT02111122

This randomized clinical trial evaluates the effect of sodium oxybate in treatment of debilitating excessive daytime sleepiness and disturbed nighttime sleep in patients with Parkinson disease.

Introduction

Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) and disturbed nighttime sleep are common and debilitating nonmotor symptoms of Parkinson disease (PD), but treatment options are scarce. Therefore, a previous open-label trial has introduced sodium oxybate, a potent central nervous system depressor and first-line treatment in narcolepsy type 1, for sleep-wake disorders in patients with PD. Although it demonstrated improvement, the open-label study’s significance is limited given the lack of a control group and objective outcome measures for sleepiness. To close this gap, the present trial examined the efficacy and safety of sodium oxybate for EDS and disturbed nighttime sleep in a double-blind, placebo-controlled electrophysiologic study.

Methods

We enrolled patients with PD (Hoehn-Yahr stage II/III) with EDS (Epworth Sleepiness Scale [ESS]>10 points) and stable dopaminergic medication. Exclusion criteria included use of sleep-inducing substances, sleep apnea, significant cognitive impairment (Montreal Cognitive Assessment <22 points),moderate to severe depression (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale questionnaire), and significant concomitant diseases.

This crossover, phase 2a trial was carried out at University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, between January 9, 2015, and February 24, 2017. It was approved by the Zurich Cantonal Ethics Committee and the national medical regulatory body Swissmedic; the protocol is available in Supplement 1. All participants gave written informed consent. There was no compensation other than travel expenses.

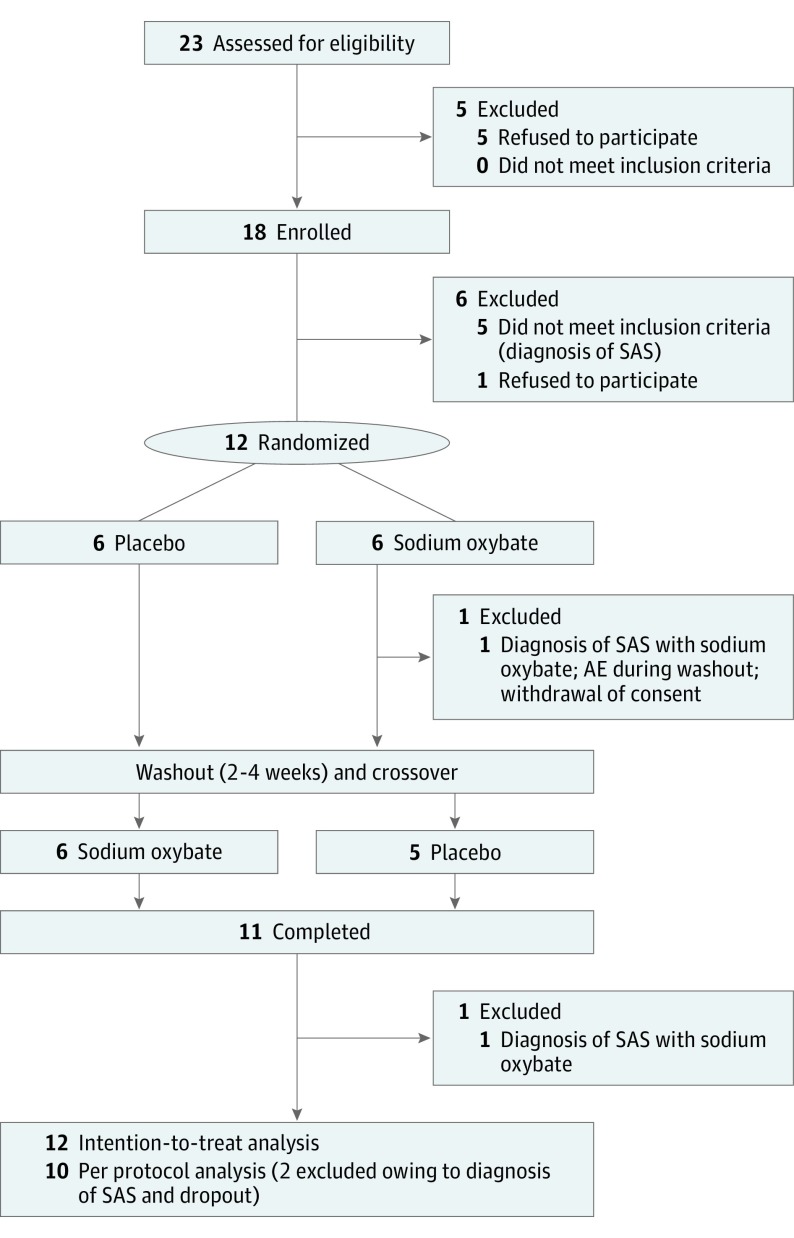

Eligible patients were screened with baseline polysomnography to rule out sleep apnea (apnea-hypopnea index >15 episodes per hour) and subsequently randomized to 1 of 2 treatment sequences (sodium oxybate followed by placebo or placebo followed by sodium oxybate, 1:1 ratio). Both medications were taken daily as drinkable solutions at bedtime and 2.5 to 4.0 hours later (standard regimen in narcolepsy) for 6 weeks with a 2- to 4-week washout period before crossover (Figure 1). In weekly alternating telephone calls and clinical visits, the dosage was titrated between 3.0 and 9.0 g per night according to efficacy and tolerability (maximum change, 1.5 g/wk). Outcome measures were evaluated in the sleep laboratory at baseline and after 6 weeks of therapy and differences were calculated both for sodium oxybate and placebo. Treatment effects were analyzed by comparing these differences, using a linear mixed model, as described below.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram and Study Design.

AE indicates adverse event; SAS, sleep apnea syndrome.

Primary efficacy end point was treatment effect on mean sleep latency (MSL), with the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) objectively quantifying EDS. Secondary end points included change of subjective EDS (assessed by ESS), sleep quality (Parkinson Disease Sleep Scale–2 [PDSS-2], questions 1-3), objective sleep parameters (in 7-hour nighttime polysomnography), off-medication motor symptoms (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, part 3 [UPDRS-III]), and quality of life (39-item PD Questionnaire [PDQ-39]). Positive treatment response was assumed when MSL increased by more than 50% or when ESS was normalized (≤10 points). Safety was assessed by monitoring adverse events (AEs) as well as routine laboratory and polysomnographic measures.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis (using R, version 0.999375-42) was primarily by intention-to-treat and secondarily by per protocol. For efficacy analysis, a linear mixed model was applied with treatment as a fixed factor (participants and treatment sequence as random factors). For evaluating carryover and period effects, we used time and sequence as fixed factors. P values were obtained by likelihood ratio tests comparing the full model with and without the effect in question. and significance was accepted at P < .05. We furthermore performed Pearson correlation to relate changes of sleep and EDS and multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify estimators of treatment response (independent variables: baseline values for age, Hoehn-Yahr stage, disease duration, UPDRS-III, ESS, MSL, and levodopa equivalent dose). Calculation of sample size was based on previous open-label study results and yielded 12 samples.

Results

We screened 18 patients in the sleep laboratory, 5 of whom were excluded owing to the polysomnographic diagnosis of sleep apnea, and 1 patient withdrew consent (Figure 1). Thus, 12 patients were randomized (10 men and 2 women; mean [SD] age, 62 [11.1] years; disease duration, 8.4 [4.6] years) (eTable 1 in Supplement 2) and, after dropout of 1 patient owing to an unrelated AE during washout, 11 patients completed the study. Two patients developed de novo sleep apnea during sodium oxybate treatment (1 was the patient who dropped out) and were excluded for the per-protocol analysis (n = 10) but included in the intention-to-treat analysis (n = 12). Mean (SD) baseline measures of EDS were 3.3 (3.0) minutes of MSL on the MSLT and 14.3 (2.3) points on the ESS. Final doses (mean [SD]) of study medication were 4.8 g (1.5 g) for sodium oxybate and 8.7 g (0.6 g) for placebo. No carryover or period effect was detected.

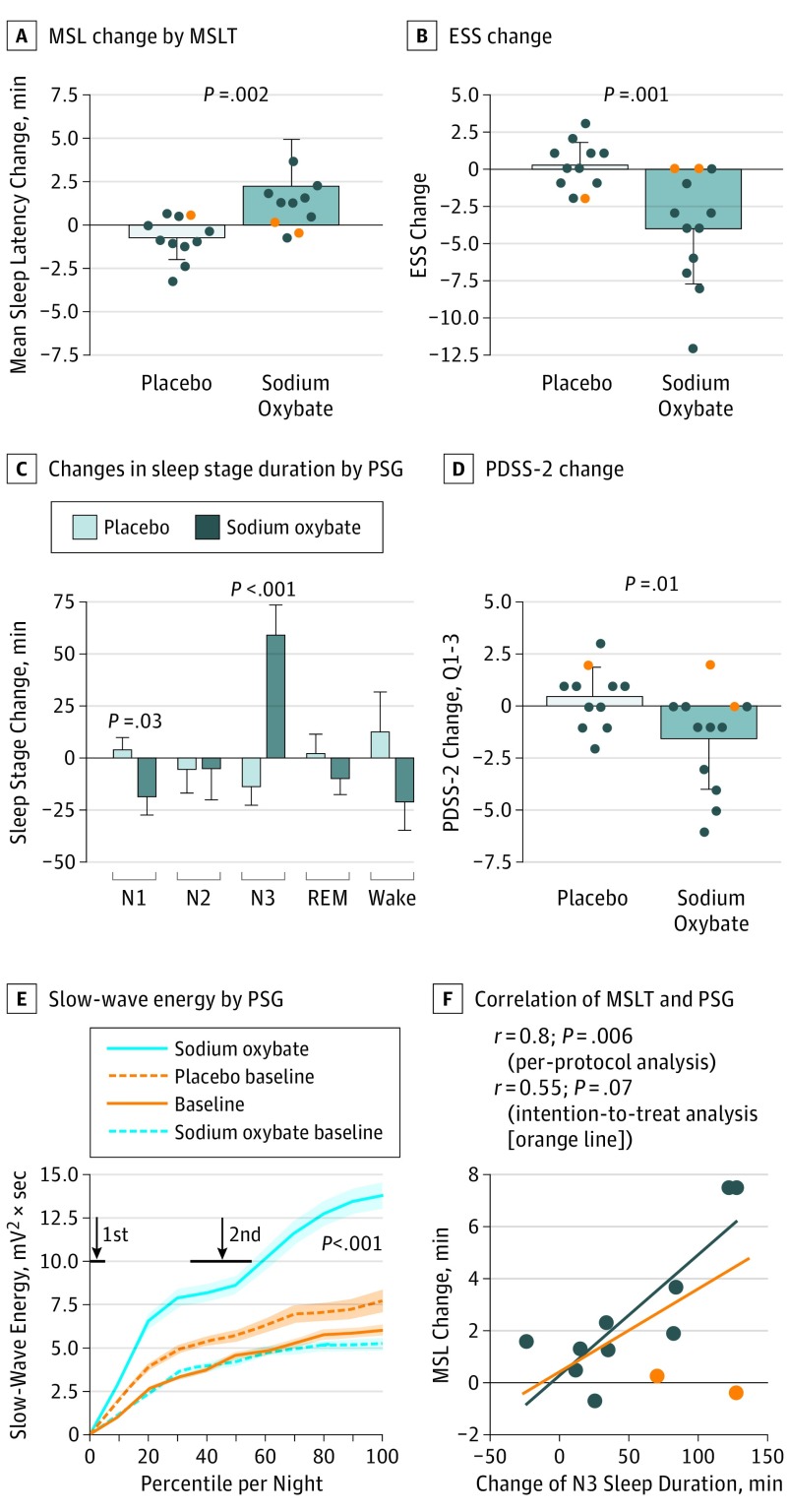

In the efficacy analysis as intention-to-treat, sodium oxybate improved EDS both objectively (+2.9 minutes MSL on the MSLT; 95% CI, 2.1 to 3.8 minutes; P = .002) (Figure 2A) and subjectively (−4.2 points on ESS; 95% CI, −5.3 to −3.0 points; P = .001) (Figure 2B), which was even more pronounced in the per-protocol analysis (+3.5 minutes MSL on the MSLT, P < .001; −5.2 points on ESS, P < .001); raw data are available in eTable 2 in Supplement 2). Responder rate was 67%, because in 8 patients the MSL on the MSLT increased clinically significantly by more than 50% during sodium oxybate treatment (placebo: 1 patient), while in 6 (50%) patients the ESS score normalized (placebo: none). None of the clinical baseline variables predicted treatment response in a multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Figure 2. Effect of Placebo vs Sodium Oxybate on Excessive Daytime Sleepiness and Nighttime Sleep.

A, Objective excessive daytime sleepiness measured by changes of mean sleep latency in the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) (baseline vs treatment). B, Subjective excessive daytime sleepiness (measured by changes in the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS). C, Objective nighttime sleep as measured by changes in durations of different sleep stages noted on polysomnography (PSG). D, Subjective nighttime sleep as measured by the Parkinson Disease Sleep Scale–2 (PDSS-2) questions 1 to 3 (Q 1-3), regarding general sleep quality and disturbances with initiation and maintenance of sleep. E, Cumulative slow-wave energy, plotted longitudinally over the course of the PSG night. The x-axis shows percentiles of individual sleep time; arrows indicate mean time points of sodium oxybate and placebo intake (ie, at lights off and 2.5-4.0 hours later). F, Correlation between change of slow-wave sleep duration and change of objective excessive daytime sleepiness (measured by mean sleep latency) during sodium oxybate treatment. Orange circles indicate 2 patients who developed a sleep apnea syndrome during sodium oxybate treatment and were excluded from the per-protocol analysis. Data are presented as means; error bars indicate SD (exception: SE for panel C for better overview). REM indicates rapid eye movement.

Sodium oxybate enhanced subjective sleep quality (−2.0 points on PDSS-2; 95% CI, −2.8 to −1.2 points; P = .02) (Figure 2C) and slow-wave sleep duration (+72.7 minutes of stage N3 sleep; 95% CI, 55.7 to 89.7; P < .001) (Figure 2D), mainly at the expense of superficial stage N1 sleep. Accordingly, slow-wave energy, a marker of deep sleep accumulation, increased significantly (+9.9 mV2 • s; 95% CI, 7.3 to 12.5 mV2 • s; P < .001) with 2 major increments in time-locked response to the intake of the first and second doses of sodium oxybate (Figure 2E). Otherwise, no significant changes were found regarding other variables of nighttime sleep, fatigue, motor symptoms, or quality of life (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). In the per-protocol analysis, improvements in objective EDS and nocturnal slow-wave sleep correlated significantly (Pearson r = 0.8; P = .006) (Figure 2F).

The safety profile of sodium oxybate seemed benign (Table). Although every patient (100%) experienced AEs while receiving sodium oxybate, the latter effects were mainly of mild (not interfering with daily activities; 75% of AEs) or maximally moderate (mild to moderate interference, 25% of AEs) intensity and largely resolved after dose adjustment (58% of AEs in 67% of patients). Thus, only 4 patients (33%) remained affected at study termination and none dropped out owing to a sodium oxybate–related AE. These individuals also displayed sleep abnormalities in polysomnography while receiving sodium oxybate treatment (2 with sleep apnea, 1 with non–rapid eye movement parasomnia, 1 with increased periodic limb movements that were already present during placebo treatment) and were nonresponders regarding EDS or sleep troubles. No significant increase of the mean apnea-hypopnea index or sign of abuse or dependency was noted.

Table. Safety Analysisa.

| Adverse Events | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Oxybate (n = 12) |

Placebo (n = 12) |

|||

| Patients Affected | Adverse Events | Patients | Adverse Events | |

| Any adverse event | 12 (100) | 28 (100) | 5 (42) | 10 (100) |

| Adverse events unrelated to study medication | 3 (25) | 4 (14) | 3 (25) | 5 (50) |

| Adverse events potentially related to study medication | 12 (100) | 24 (86) | 3 (25) | 5 (50) |

| Mild intensity | 8 (67) | 18 (75) | 3 (100) | 5 (100) |

| Moderate intensity | 4 (33) | 6 (25) | 0 | 0 |

| Severe intensity | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Improvement after dose adjustment or spontaneously | 12 (100) | 14 (58) | 3 (25) | 4 (80) |

| Mild dizziness and asthenia | 6 (50) | 6 (43) | 1 (8) | 1 (25) |

| Mild nausea | 2 (17) | 2 (14) | 0 | 0 |

| Mild deterioration of PD motor symptoms | 1 (8) | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| Mild thoracic discomfort | 1 (8) | 1 (7) | 1 (8) | 1 (25) |

| Short episode with dyspnea at night | 1 (8) | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| Mild leg cramps | 1 (8) | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| Nocturesis (once) | 1 (8) | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| Mild diarrhea | 1 (8) | 1 (7) | 0 | 0 |

| Mild dry mouth | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 1 (25) |

| Mild headache | 0 | 0 | 1 (8) | 1 (25) |

| Without improvement after dose adjustment | 4 (33) | 10 (42) | 1 (8) | 1 (20) |

| Obstructive sleep apnea syndromeb | 2 (17) | 2 (20) | 0 | 0 |

| NREM parasomniab | 1 (8) | 1 (10) | 0 | 0 |

| Increased periodic limb movementsb | 1 (8) | 1 (100) | ||

| Moderate weight loss | 1 (8) | 1 (10) | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate nervousness | 1 (8) | 1 (10) | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate dizziness | 2 (17) | 2 (20) | 0 | 0 |

| Moderate deterioration of motor symptoms | 2 (17) | 2 (20) | 0 | 0 |

| Mild lack of drive | 1 (8) | 1 (10) | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: NREM, non–rapid eye movement; PD, Parkinson disease.

Data are number of patients with an adverse event (percentage within study population) and total number of adverse events (percentage of all adverse events in the respective category). No severe adverse events were reported and no patients dropped out owing to treatment-related adverse events.

Determined on polysomnography.

Discussion

The present study provides class I evidence for the efficacy of sodium oxybate in treating sleep-wake disturbances in PD. This finding is based on the extensive, electrophysiologically proven treatment effect that, to our knowledge, is unmatched by any other intervention reported so far. Under the premise of stringent monitoring (including regular clinical and polysomnographic follow-up), the safety profile seems benign as no sodium oxybate–related AE led to study discontinuation; however, further studies with longer treatment durations and larger sample sizes are warranted.

There was a reciprocal association between nighttime sleep and EDS. Sodium oxybate–related improvements of sleep and EDS correlated significantly, whereas sodium oxybate–induced sleep disturbances predicted insufficient treatment response and AEs.

Strengths and Limitations

A study strength is that our efficacy and safety results correspond with evidence from large narcolepsy trials and the study by Ondo et al, with few exceptions. For instance, we found no effect on fatigue, which may be related to differences in study population (eg, lower baseline fatigue level), placebo-controlled study design, or lower final sodium oxybate dosage.

The main limitation of the present study is the limited number of participants. While the number was sufficient to provide class I evidence regarding efficacy outcomes in accordance with the initial sample size calculation and the observed strong therapy effect, we cannot conclude on safety outcomes with the same level of evidence. Hence, larger follow-up trials are necessary.

Conclusions

Sodium oxybate may be a powerful novel treatment option for sleep-wake disturbances in PD. However, stringent monitoring is necessary (as already established in many countries for sodium oxybate in narcolepsy through regulatory restrictions) and larger follow-up trials with longer treatment durations are warranted for validation.

Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics and Final Dosages of Study Medications

eTable 2. Effect of Sodium Oxybate and Placebo on Daytime Vigilance, Nighttime Sleep, Parkinson Disease Symptoms

References

- 1.Pandey S, Bajaj BK, Wadhwa A, Anand KS. Impact of sleep quality on the quality of life of patients with Parkinson’s disease: a questionnaire based study. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;148:29-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ozdilek B, Gunal DI. Motor and non-motor symptoms in Turkish patients with Parkinson’s disease affecting family caregiver burden and quality of life. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(4):478-483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chahine LM, Amara AW, Videnovic A. A systematic review of the literature on disorders of sleep and wakefulness in Parkinson’s disease from 2005 to 2015. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;35:33-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Busardò FP, Kyriakou C, Napoletano S, Marinelli E, Zaami S. Clinical applications of sodium oxybate (GHB): from narcolepsy to alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19(23):4654-4663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scammell TE. The neurobiology, diagnosis, and treatment of narcolepsy. Ann Neurol. 2003;53(2):154-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ondo WG, Perkins T, Swick T, et al. Sodium oxybate for excessive daytime sleepiness in Parkinson disease: an open-label polysomnographic study. Arch Neurol. 2008;65(10):1337-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Herrmann C. International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res. 1997;42(1):17-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumann CR, Werth E, Stocker R, Ludwig S, Bassetti CL. Sleep-wake disturbances 6 months after traumatic brain injury: a prospective study. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 7):1873-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trenkwalder C, Kohnen R, Högl B, et al. Parkinson's disease sleep scale: validation of the revised version PDSS-2. Mov Disord. 2011;26(4):644-652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo CE, et al. , eds. The AASM Scoring Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications, Version 2. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Movement Disorder Society Task Force on Rating Scales for Parkinson’s Disease The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS): status and recommendations. Mov Disord. 2003;18(7):738-750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Peto V, Jenkinson C, Fitzpatrick R, Greenhall R. The development and validation of a short measure of functioning and well being for individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(3):241-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.R Development Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: The R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bates D, Maechler M, Bolker B lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using S4 classes; R package version 0.999375-42. 2012. http://cran.R-project.org/package=lme4. Accessed August 1, 2015.

- 16.Pinheiro JC, Bates DM. Mixed-Effects Models in S and S-PLUS. New York, NY: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumann-Vogel H, Imbach LL, Sürücü O, et al. The impact of subthalamic deep brain stimulation on sleep-wake behavior: a prospective electrophysiological study in 50 Parkinson patients. Sleep. 2017;40(5). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Videnovic A, Klerman EB, Wang W, Marconi A, Kuhta T, Zee PC. Timed light therapy for sleep and daytime sleepiness associated with Parkinson disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(4):411-418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang YG, Swick TJ, Carter LP, Thorpy MJ, Benowitz NL. Safety overview of postmarketing and clinical experience of sodium oxybate (Xyrem): abuse, misuse, dependence, and diversion. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(4):365-371. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alshaikh MK, Tricco AC, Tashkandi M, Mamdani M, Straus SE, BaHammam AS. Sodium oxybate for narcolepsy with cataplexy: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(4):451-458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Protocol

eTable 1. Baseline Characteristics and Final Dosages of Study Medications

eTable 2. Effect of Sodium Oxybate and Placebo on Daytime Vigilance, Nighttime Sleep, Parkinson Disease Symptoms