Abstract

This survey study investigates whether physician experiences with members of their social network are associated with their recommendations for breast cancer screening.

Physician recommendations strongly influence women’s decisions to receive breast cancer screening, but current evidence suggests physician adherence to evolving guidelines that recommend less screening is suboptimal. Clinical encounters and experiences with friends, colleagues, and family members who have been diagnosed with breast cancer may affect physician screening recommendations. These personal and professional experiences may provide physicians with anecdotal information about breast cancer screening fundamentally different from—and potentially at odds with—scientific evidence that relies on estimates of mortality reduction.

With information from a national survey of gynecologists and primary care physicians, we investigated whether physician experiences with patients, friends, colleagues, and family members diagnosed with breast cancer were associated with their recommendations for breast cancer screening.

Methods

The Breast Cancer Social Networks study (CanSNET) is a national mailed survey fielded from May 2016 to September 2016 that included 2000 primary care physicians randomly selected from the American Medical Association Masterfile. Participants included gynecologists and internal medicine, family medicine, and general practice physicians who were surveyed about their breast cancer screening practices. Approval for this study was obtained from and signed patient consent was waived by the institutional review board at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

Physicians reported up to 2 women members of their social network (1 patient and 1 friend or family member) who had been diagnosed with breast cancer and “whose cancer, broadly speaking, had the greatest impact” on them. Experiences of the individuals with breast cancer were categorized as follows: (1) diagnosed by screening, good prognosis; (2) not diagnosed by screening, good prognosis; (3) diagnosed by screening, poor prognosis; (4) not diagnosed by screening, poor prognosis; and (5) screening or prognosis unknown. Poor prognosis was defined as metastatic disease at diagnosis or dying of cancer. Physicians were asked whether they generally recommended routine screening mammograms to average-risk women (no family history or previous breast issues) in age groups for which existing guidelines are discordant (aged 40-44, 45-49, and ≥75 years). We used logistic regression models in SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc), which adjusted for physician characteristics and used separate models for each age group, to test whether reporting at least 1 social network member in a diagnosis/prognosis category was associated with recommending routine breast cancer screening.

Results

Of the 871 physicians who responded (adjusted response rate, 52.3%), 23 physicians did not report on any social network member, leaving a sample of 848 physicians. Of these, 461 (54.4%) were men, 379 (44.7%) were general practitioners or specialized in family medicine, 246 (29.0%) in internal medicine, and 223 (26.3%) in gynecology. These 848 physicians reported on 1631 social network members, including 771 patients, 381 family members, 474 other social network members, and 5 social network members with missing values for their position in the network (Table). Of the social network members, 305 of 1631 women (18.6%) had a poor prognosis, and more than half of these (163 women) were not diagnosed by breast cancer screening. There were 20 social network members with missing diagnosis or prognosis information.

Table. Characteristics of the CanSNET Physician Sample.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Total physician sample | 848 (100)a |

| Physician specialty | |

| Internal medicine | 246 (29.0) |

| Family medicine/general practitioner | 379 (44.7) |

| Gynecology | 223 (26.3) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 461 (54.4) |

| Female | 387 (45.6) |

| Years since residency graduation, yb | |

| ≤10 | 135 (15.9) |

| 11-20 | 236 (27.8) |

| >20 | 458 (54.0) |

| Physician race/ethnicityb | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 605 (71.3) |

| Asian | 112 (13.2) |

| Other | 103 (12.2) |

| Diagnosis/prognosis of social network membersb,c | |

| Diagnosed by screening/good prognosis | 893 (54.8) |

| Not diagnosed by screening/good prognosis | 252 (15.5) |

| Diagnosed by screening/poor prognosis | 142 (8.7) |

| Not diagnosed by screening/poor prognosis | 163 (10.0) |

| Diagnosis or prognosis unknown | 161 (9.9) |

| Relationship to social network member | |

| Patient | 771 (47.3) |

| First-degree relative | 119 (7.3) |

| Other relative | 262 (16.1) |

| Other social network member | 474 (29.1) |

| Age of social network member at diagnosis, mean (SD), y | 51.2 (12.4) |

Abbreviation: CanSNET, Breast Cancer Social Networks study.

Of 871 eligible physicians, 23 did not report on any social network member leaving a sample of 848 physicians.

Number not consistent with total sample size and percentage less than 100% because of missing values.

Twenty social network members had either missing screening or prognosis information.

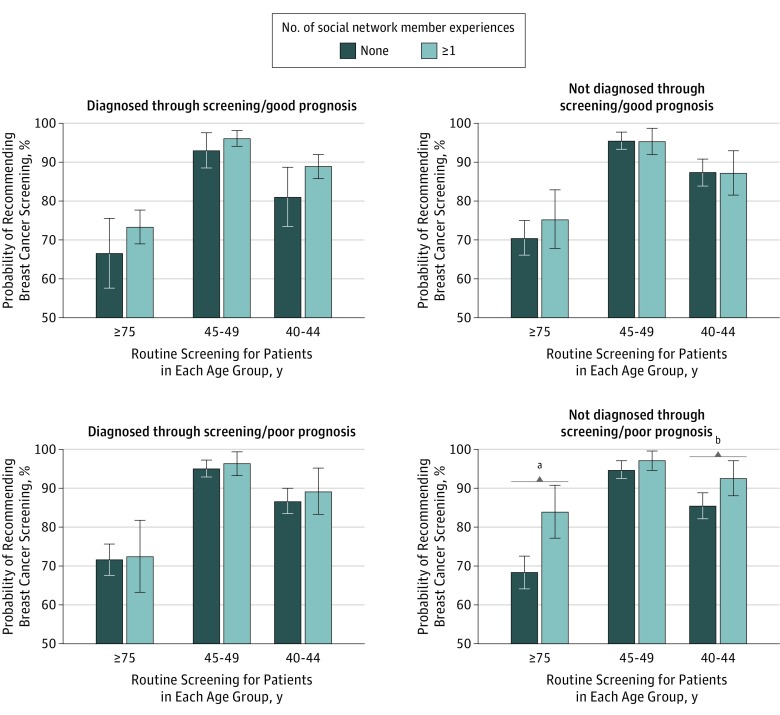

Physicians who reported at least 1 social network member with a poor prognosis who was not diagnosed by screening were significantly more likely to recommend routine screening to women aged 40 to 44 years and those 75 years or older compared with physicians who did not report a social network member in this category (predicted probability for women aged 40-44 years: 92.7% vs 85.6%, P = .009; for women ≥75 years: 84.0% vs 68.3%, P < .001; Figure). The association between experiences and screening recommendations did not vary by the type of social network member (eg, patient, family member).

Figure. Probabilities and 95% CIs of Recommending Breast Cancer Screening to Women in Different Age Groups According to Whether the Physician Reported an Experience in Each Diagnosis and Prognosis Category.

Models adjust for physician medical specialty, sex and race/ethnicity of physician, years since residency graduation, relationship to social network member, medical practice size, employment type, proportion of uninsured patients in medical practice, full- vs part-time employment, and involvement in lawsuit for failure to diagnose cancer, with all covariates set at their means. Models used multiple imputation methods and chained equations to account for missing data.

aP < .001.

bP = .009.

Discussion

Physicians recounted detailed experiences of social network members, such as patients, friends, colleagues, and family members, who were diagnosed with breast cancer. Though the majority of physicians reported members who had good prognoses, a larger proportion of physicians recounted experiences with a poor prognosis than would be expected based on national averages (where 6% of women with breast cancer are diagnosed with distant disease). Disproportionate recall of these bad experiences is in line with the abundant behavioral literature that highlights how dreaded outcomes are more easily remembered, which can increase perceived risk. Describing a woman whose breast cancer was not diagnosed by screening mammogram and who had a poor prognosis was associated with increased odds of recommending routine screening to patients within the designated younger and older age groups for which guidelines no longer support routine, universal screening. Our results suggest that helping clinicians reflect on how their experiences influence their current screening patterns may be an important approach to improve adherence to revised breast cancer screening guidelines.

References

- 1.Meissner HI, Breen N, Taubman ML, Vernon SW, Graubard BI. Which women aren’t getting mammograms and why? (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2007;18(1):61-70. doi: 10.1007/s10552-006-0078-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haas JS, Sprague BL, Klabunde CN, et al. ; PROSPR (Population-based Research Optimizing Screening through Personalized Regimens) Consortium . Provider attitudes and screening practices following changes in breast and cervical cancer screening guidelines. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(1):52-59. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3449-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Radhakrishnan A, Nowak SA, Parker AM, Visvanathan K, Pollack CE. Physician breast cancer screening recommendations following guideline changes: results of a national survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):877-878. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welch HG, Frankel BA. Likelihood that a woman with screen-detected breast cancer has had her “life saved” by that screening. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(22):2043-2046. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67(1):7-30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finucane ML, Alhakami A, Slovic P, Johnson SM. The affect heuristic in judgments of risks and benefits. J Behav Decis Making. 2000;13(1):1-17. doi: [DOI] [Google Scholar]