Abstract

This population-based study examines the changes in use of atypical antipsychotic medication in young children with peer review prior authorization policies.

In response to the growing cardiometabolic safety concerns about the use of atypical antipsychotic (AAP) medications in children, several state Medicaid agencies have adopted a novel, more clinically nuanced and individualized approach to reviewing the appropriateness of AAP use, namely, peer review prior authorization (PA) policies. Physicians must receive preapproval through contracted clinicians (peer reviewers) to prescribe AAPs to certain-aged children. We assessed the effect of peer review PA policies on AAP use among Medicaid-insured youth according to age restriction criteria.

Methods

We used Medicaid administrative claims data from 4 geographically diverse states wherein AAP-related peer review PA policies were implemented between April 2008 and August 2009. Data analysis was conducted from November 4, 2014, to June 12, 2017. Peer review policies were implemented for children younger than 8 years in state A, younger than 6 years in states B and C, and younger than 5 years in state D. We used an interrupted time-series design to assess monthly and quarterly use of AAPs across 36 months, including 12-month prepolicy, 12-month transition, and 12-month postpolicy analysis. The unit of analysis was child with any AAP dispensing. The 12-month transition period represented 6 months before and after the policy implementation date in each state. The study was an extension of an interagency agreement between the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid and the US Food and Drug Administration’s Safe Use Initiative. The US Food and Drug Administration Research in Human Subjects Committee determined that the study does not qualify as human research (records review with no identifiers). In multivariable logistic regression models with generalized estimating equations, we added interaction terms for time period and age group to assess whether changes in AAP use differed by age group in the postpolicy vs prepolicy periods.

Results

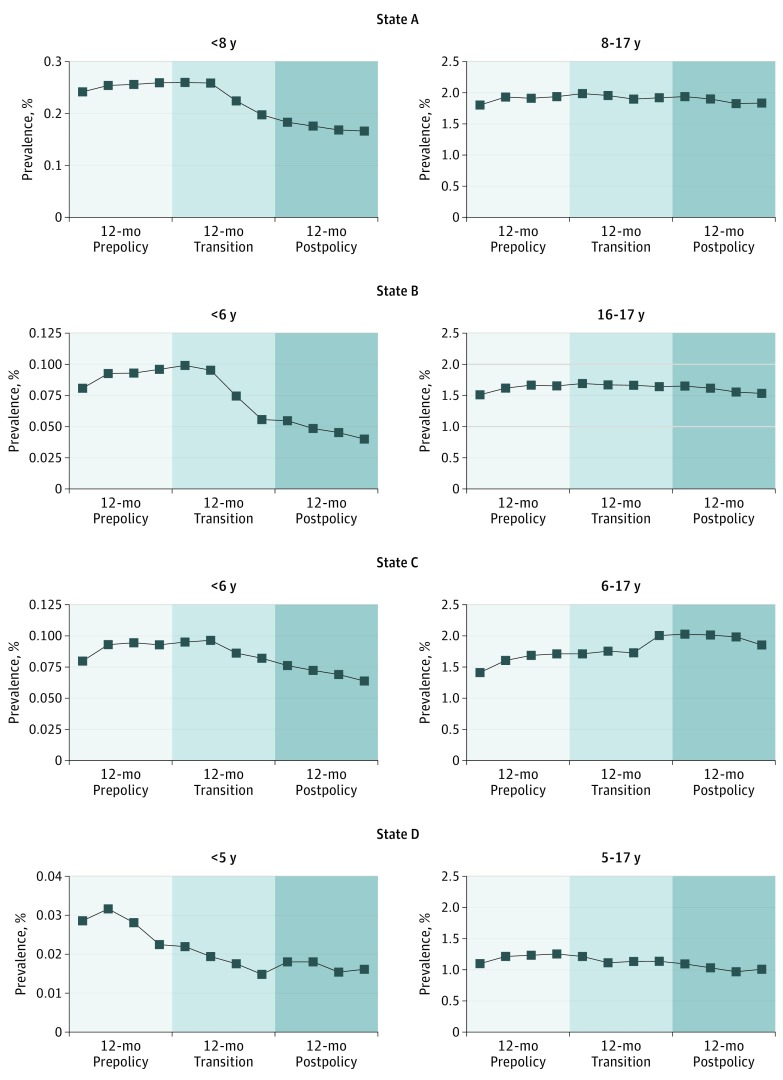

Compared with the prepolicy period, AAP prevalence after policy implementation decreased significantly from 0.25% to 0.17% (odds ratio [OR], 0.68; 95% CI, 0.64-0.72) for children younger than 8 years in state A, from 0.09% to 0.05% (OR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.50-0.66) for children younger than 6 years in state B, from 0.09% to 0.07% (OR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.69-0.84) for children younger than 6 years in state C, and from 0.03% to 0.02% (OR, 0.64; 95% CI, 0.46-0.88) for children younger than 5 years in state D (Table and Figure).

Table. Changes in the Mean Monthly Prevalence of AAP Use Among Medicaid-Insured Youth Following Implementation of Peer Review Prior Authorization Policies According to Age Restriction Criteriaa.

| Age Group, y | Monthly Prevalence, % | Adjusted OR (95% CI)b | Interaction P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-mo Prepolicy Period | 12-mo Transition Period | 12-mo Postpolicy Period | |||

| State A | |||||

| <8 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.17 | 0.68 (0.64-0.72) |

<.001 |

| 8-17 | 1.90 | 1.94 | 1.87 | 1.06 (1.04-1.08) |

|

| State B | |||||

| <6 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.57 (0.50-0.66) |

<.001 |

| 6-17 | 1.61 | 1.67 | 1.59 | 1.08 (1.06-1.10) |

|

| State C | |||||

| <6 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.07 | 0.76 (0.69-0.84) |

<.001 |

| 6-17 | 1.61 | 1.80 | 1.97 | 1.34 (1.31-1.36) |

|

| State D | |||||

| <5 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.64 (0.46-0.88) |

.03 |

| 5-17 | 1.20 | 1.15 | 1.03 | 0.93 (0.90-0.95) |

|

Abbreviations: AAP, atypical antipsychotic; OR, odds ratio.

Age group was defined according to the age restriction criteria set by the prior authorization policies in the 4 study states. In state A, the policy applied to children younger than 8 years; in states B and C, the policy applied to children younger than 6 years; and in state D, the policy applied to children younger than 5 years.

Adjusted OR for AAP use in the postpolicy period compared with AAP use in the prepolicy period. The models included variables for age group, time period (12-month postpolicy period vs 12-month prepolicy period), interaction term for age group and time period (age group × time period), race/ethnicity, sex, Medicaid eligibility group, and payment system type (fee-for-service vs managed care).

Figure. Policy-Related Trends in the Mean Quarterly Prevalence of Atypical Antipsychotic Use Across 36 Months Among Medicaid-Insured Youth According to Age Restriction Criteria.

Age group was defined according to the age restriction criteria set by the peer review prior authorization policies for atypical antipsychotic prescribing to Medicaid-insured youth in the 4 study states. In state A, the policy applied to children younger than 8 years; in states B and C, children younger than 6 years; and in state D, children younger than 5 years.

Among older youth (lacking peer review), AAP use increased significantly in states A, B, and C. Although there was a decrease in AAP use in both older (5-17 years) and younger (<5 years) groups in state D, the decrease was significantly greater only in children younger than 5 years (interaction P = .03).

Discussion

With the implementation of the peer review PA policies instituted in 4 geographically diverse state Medicaid programs, AAP use declined substantially in children younger than 5 to 8 years. The policy generally had little or no discernible effect on AAP use in older youth, possibly reflecting evidence-based practice.

These findings are consistent with recent national estimates suggesting that the rapid increase in AAP use among publicly insured young children had stabilized since 2008. However, challenges exist, such as growing use of complex AAP regimens and low uptake of recommended cardiometabolic monitoring. Educationally oriented peer review, as demonstrated in state D, may account for spillover effects among older youth who were not similarly monitored.

The study is limited by the inability to control for all the external factors that may affect prescribing patterns. Moreover, the findings may not be nationally representative and do not imply clinical appropriateness. Nonetheless, our study reports significant decreases in AAP use among Medicaid-insured young children following the implementation of these peer review PA policies and motivates research on the long-term consequences of these policies on clinical outcomes.

References

- 1.Egger H. A perilous disconnect: antipsychotic drug use in very young children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(1):3-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burcu M, Zito JM, Safer DJ, et al. Concomitant use of atypical antipsychotics with other psychotropic medication classes and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56(8):642-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmid I, Burcu M, Zito JM. Medicaid prior authorization policies for pediatric use of antipsychotic medications. JAMA. 2015;313(9):966-968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-experiments: interrupted time-series designs In: Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT, eds. Experimental and Quasi-Experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin Co; 2002:171-206. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crystal S, Mackie T, Fenton MC, et al. Rapid growth of antipsychotic prescriptions for children who are publicly insured has ceased, but concerns remain. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(6):974-982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zito JM. Advancing the quality of pediatric antipsychotic use: maybe it takes a PAL. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(2):555-560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]