Key Points

Question

Are preference-based instruments sensitive to changes in well-being and reduced quality of life associated with fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) in people with early-stage melanoma?

Findings

The preference-based instrument Assessment of Quality of Life–8-Dimension Scale (AQoL-8D) was more sensitive to changes in psychological health and FCR than the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Melanoma instrument. High FCR was associated with a significant decrease in quality of life for people with melanoma.

Meaning

Loss of utility attributable to FCR is an important quality-of-life issue signaling a need for intervention in melanoma care, and the AQoL-8D is a valid and sensitive measure that can be used to assess utility-based health states.

Abstract

Importance

The diagnosis of a life-threatening disease like melanoma can affect all aspects of a person’s life, including health-related quality of life (HRQOL) and psychological aspects of melanoma such as fear of cancer recurrence (FCR). Economic evaluations of psychological interventions require preference-based (utility) instruments that are sensitive to changes in well-being and HRQOL; however, very few studies have evaluated the sensitivity of these instruments when used for people with melanoma.

Objective

To compare utility scores from the multiple-attribute instrument Assessment of Quality of Life—8-Dimension Scale (AQoL-8D) with the mapped utility scores of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Melanoma (FACT-M) and to investigate the sensitivity of both instruments in identifying the influence of FCR on HRQOL.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This assessment of data from a randomized clinical trial of a psychoeducational intervention to reduce FCR, conducted at 3 high-risk melanoma clinics in Australia, evaluated 164 patients with early-stage melanoma and a high risk of developing a second primary melanoma.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The FACT-M and AQoL-8D were used to assess HRQOL and FCR among the study participants. Concurrent validity was assessed by comparing the total and subdomain scores of the 2 instruments, and the strength of associations was assessed using Pearson correlation coefficient. Convergent validity was assessed by comparing participants’ HRQOL, demographic, and clinical characteristics using the χ2 test and F statistic. Both the FACT-M and AQoL-8D utilities were regressed on FCR Inventory (FCRI) severity scores to estimate the effect of elevated FCR on HRQOL.

Results

A total of 164 participants completed the baseline questionnaires, but only 163 met all inclusion criteria and underwent the full analysis: 72 were women; 91 were men; and mean (SD) age was 58.2 (12.1) years. Both the AQoL-8D and FACT-M instruments showed good concurrent validity and could differentiate between relevant subgroups including level of FCRI severity. The AQoL-8D and FACT-M utilities were strongly correlated (r2 = 0.57). Respondents had a mean (SD) AQoL-8D utility of 0.77 (0.2), and a mean (SD) FACT-M utility score of 0.76 (0.07). High levels of FCRI severity were associated with a decrease in utility of 0.12 (95% CI, −0.19 to −0.05) as measured by AQoL-8D, and a decrease of 0.03 (95% CI, −0.05 to −0.01) as measured by the FACT-M.

Conclusions and Relevance

For economic evaluations of psychological interventions in melanoma, the AQoL-8D and FACT-M are valid measures of utility; however, the AQoL-8D demonstrates greater sensitivity to FCRI severity. Our results suggest a significant association between FCR and HRQOL.

This study uses randomized clinical trial data to compare utility scores from the AQoL-8D and the FACT-M and evaluate the sensitivity of both instruments in identifying the influence of fear of cancer recurrence on health-related quality of life in patients with early-stage melanoma.

Introduction

The diagnosis of a life-threatening disease such as melanoma has the potential to affect all aspects of a person’s life, including his or her quality of life. Around 90% of patients will survive melanoma but will remain at risk of new primary disease or disease progression for at least 10 years after diagnosis. As a consequence, melanoma survivors often experience anxiety and fear of cancer recurrence (FCR); FCR is one of the most commonly reported psychological difficulties among people with a history of melanoma. The psychological burden associated with FCR is well established; FCR has been associated with increased levels of depression, anxiety and stress, lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL), and impaired social functioning. The relationship between these psychological factors and FCR is most likely bidirectional; however, the burden of reduced psychological health and HRQOL due to high FCR remains unclear in the current literature.

Health-related quality of life refers to an aggregate of an individual’s responses to a collection of questions about aspects of their health. Operationalized as utilities, HRQOL is used in economic evaluations to provide a numeric value for a particular health state.

Generally, HRQOL is evaluated with instruments designed to subjectively assess the effect of the disease and outcomes of treatment on the physical, psychological, and social well-being of patients. There are 2 main types of survey-based instruments that can be used to measure the effects of a health state on an individual’s quality of life: multiple-attribute utility instruments, and disease-specific “profile” instruments. For disease-specific instruments such as the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Melanoma (FACT-M), individual item responses are summed to generate an overall HRQOL score. Disease-specific instruments are most commonly used in clinical trial settings and have been shown to be reliable, responsive to change, and to have good convergent and concurrent validity. There are, however, very limited data on whether disease-specific instruments are sensitive to differences in psychological health or emotional well-being. This can limit their ability to capture the full benefits of interventions, particularly when evaluating the cost-effectiveness of psychological interventions and services.

Using measurement tools that are sensitive to psychological aspects of melanoma is important for the evaluation of psychological care for people affected by this disease. The Assessment of Quality of Life–8-Dimension Scale (AQoL-8D) is a relatively new preference-based (utility) instrument reported to be sensitive to changes in mental and emotional health, and it therefore may be more useful in economic evaluations of interventions to treat psychological difficulties experienced by people with melanoma.

Thus, the first aim of this study was to examine the association between AQoL-8D and FACT-M mapping-derived utility scores to determine the magnitude of their empirical association, as a prerequisite for making further comparisons. The second aim was to assess the sensitivity of the AQoL-8D and FACT-M to FCR severity, as measured using the FCR Inventory (FCRI) severity scale. We hypothesized that higher levels of FCR severity would be associated with lower utility scores measured using the AQoL-8D and FACT-M.

Methods

Data were obtained from a randomized clinical trial (RCT) of a psychoeducational intervention to reduce FCR in people with melanoma at high risk of developing another primary melanoma. The trial was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN identifier: 12613000304730). Approval was obtained from all participating institutions’ ethics committees, and all participants provided their written informed consent.

The primary aim of the RCT was to evaluate the effectiveness of a multifaceted psychoeducational intervention, timed in conjunction with participants’ dermatological appointments, in reducing FCR in people attending 1 of 3 high-risk melanoma clinics across New South Wales, Australia. All participants had at least 1 previous melanoma diagnosed at American Joint Cancer Committee (AJCC) stage 0-II and were at high risk of developing another primary melanoma owing to the presence of dysplastic nevus syndrome and/or multiple previous melanomas. The study also evaluated the effect of the intervention on anxiety, depression, stress, quality of life, unmet needs, satisfaction with clinical care, melanoma-related knowledge, and melanoma-related health behaviors. In the RCT, 164 participants were randomized, with 80 randomly allocated to the intervention arm and 84 to the control arm. All 164 participants completed the HRQOL and FCR questionnaires at the time of participant enrolment into the trial (baseline), prior to any psychological intervention, and were included in this analysis.

Instrument Description

All participants’ HRQOL was assessed using 2 measures: the AQoL-8D and the FACT-M. Their FCR was assessed using the FCRI. A full description of the 3 instruments is provided in the eAppendix in the Supplement.

Analysis

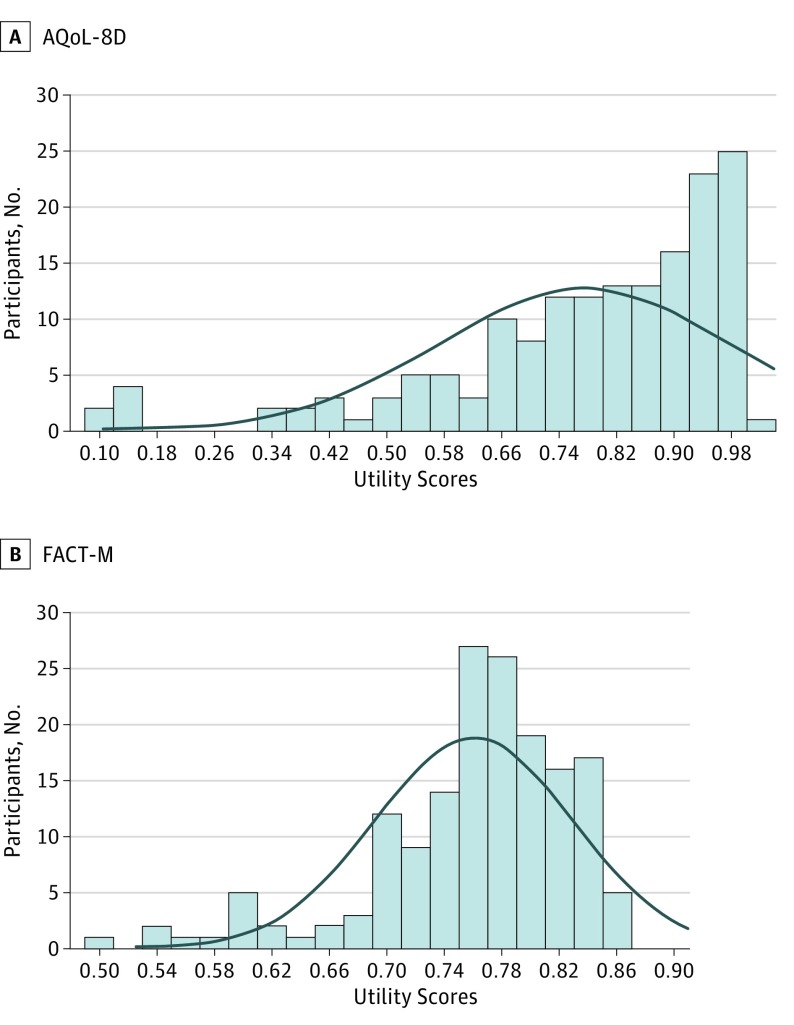

Baseline utilities for the AQoL-8D and FACT-M were reported as descriptive statistics, with histograms to show distributions. The FACT-M scores were transformed to utilities using a published algorithm.

We would expect the utility scores from the 2 instruments to be correlated if they were both sensitive to variations in HRQOL. This correlation property was used to test the concurrent validity of the AQoL-8D and FACT-M; specifically, we looked for positive correlation of the AQoL-8D with the independently validated FACT-M measure. Comparisons of the overall AQoL-8D and its 2 super dimensions with each of the component dimension scores of the FACT-M were carried out. A failure of the instrument to correlate with any of the component dimensions would suggest insensitivity of the AQoL-8D to that dimension. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to ascertain the strength of associations between the 2 instruments and were interpreted using the Cohen approach; a correlation of approximately 0.50 was considered a moderate to strong association; 0.30, moderate; and 0.1, weak.

As a supplementary analysis, we assessed responsiveness in terms of floor and ceiling effects. Ceiling effects were determined by the percentage of participants reporting full health in each dimension (a value of 1 indicates full health), and floor effects were assessed by the percentage of patients reporting very low health in each dimension (0.0-0.2).

The ability of the instruments to differentiate between different relevant subgroups (convergent validity) was also tested. We conducted a comparison of participants’ AQoL-8D and FACT-M total scores by their demographic and clinical characteristics. In the subgroup analysis, categorical groups were compared using χ2 tests. For FCR severity, participants were categorized into those reporting normal FCR or high FCR based on the clinical cutoff score of 13. This cutoff is generally considered an indicator of the need for referral to clinical psychological services. Statistical significance of the strength of the relationship between model predictors (demographic and clinical characteristics) and the response variable (utility scores) is reported with the F statistic at the 5% level.

We also tested whether higher FCRI severity scores were associated with lower utility scores using stepwise multivariate linear regressions with backward selection including all variables with P < .20. As a secondary analysis, we conducted a simultaneous-entry regression analysis. These models included all demographic and clinical characteristics reported in Table 1. Scores for both the AQoL-8D and FACT-M were regressed on FCRI severity scores and the other variables. All regression assumptions were checked. We analyzed the incremental change in AQoL-8D scores with an increase in FCRI severity scores, conducting the same analysis for the FACT-M for comparison. All analyses were carried out independently in SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute Inc) by 2 analysts (M.D. and A.T.).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Melanoma Characteristics of Study Participants.

| Characteristic | Participants, No./Overall No. (%) (N = 164) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 92/164 (56.1) |

| Female | 72/164 (43.9) |

| Residence area | |

| Metropolitan | 109/164 (66.5) |

| Regional | 40/164 (24.4) |

| Rural | 15/164 (9.1) |

| Country of birth | |

| Australia | 141/164 (86.0) |

| Other | 23/164 (14.0) |

| English speaker | 163/163 (100) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 139/164 (84.8) |

| Other | 25/164 (15.2) |

| Highest level of completed education | |

| Primary school/other | 4/162 (2.5) |

| High school/leaving certificate | 43/162 (26.5) |

| Vocational/certificate | 53/162 (32.7) |

| University degree | 62/162 (38.3) |

| Confidence with medical forms | |

| Confident | 149/163 (91.4) |

| Somewhat confident | 7/163 (4.3) |

| Not confident | 7/163 (4.3) |

| Previous melanomas, mean (SD), No. (n = 157) | 2.6 (2.2) |

| Time since first melanoma, mean (SD), y (n = 159) | 13.8 (9.5) |

| Time since last melanoma, mean (SD), y (n = 159) | 7.6 (6.5) |

| AJCC stage of melanoma | |

| 0 | 5/154 (3.2) |

| I | 96/154 (62.3) |

| II | 53/154 (34.4) |

| Dysplastic nevus syndrome present | 89/164 (54.3) |

| Dysplastic nevus syndrome absent | 75/164 (45.7) |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Cancer Committee.

Results

A total of 183 eligible individuals were enrolled in the study, with a total of 164 participants completing the baseline questionnaire. Responses to several items in the FACT-M were missing for 1 participant, resulting in a total of 163 participants who fully completed the questionnaires and were included in this analysis. The majority of the sample were men (n = 91, 56%); the mean (SD) age was 58.2 (12.1) years; and the mean (SD) number of melanomas per participant was 2.6 (2.2) (Table 1). Two-thirds of the sample (n = 109) reported FCRI severity scores indicative of the need for clinical intervention. Internal consistency of both instruments was tested using the Cronbach α. The α coefficients of 0.85 for AQoL-8D and 0.84 for FACT-M suggest good internal consistency for both instruments.

AQoL-8D Scores Compared With FACT-M Scores

FACT-M responses were transformed from scores of 0 to 204 to a 0.00 to 1.00 scale for comparison with the AQoL-8D using a published algorithm. The resulting frequency distributions for utilities derived from the 2 instruments are presented in Figure 1. The AQoL-8D scores were negatively skewed. Respondents had a mean (SD) AQoL-8D utility score of 0.77 (0.2) with a range of 0.1 to 1.0. The mean (SD) FACT-M utility score was 0.76 (0.07) with a range of 0.5 to 0.86.

Figure 1. Frequency Distribution of Participant Quality-of-Life Scores.

There were a total of 163 participants normally distributed, as indicated by the curved lines; Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, Pr > D is 0.010. AQoL-8D indicates the Assessment of Quality of Life–8-Dimension scale; FACT-M, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Melanoma scale.

A correlation of 0.57 between overall scores on the AQoL-8D and FACT-M indicates a moderate to strong relationship between the 2 instruments (Table 2). The AQoL-8D mental health dimension was strongly correlated with the FACT-M overall score (0.61) and with the emotional well-being component (0.51).

Table 2. Correlation Matrix for the AQoL-8D and FACT-M (Concurrent Validity).

| AQoL-8D | FACT-M | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Utility | MSD | PSD | PWB | SWB | EWB | FWB | FACT-M Total | |

| AQol-8D | Utility | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| MSD | 0.906a | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| PSD | 0.787a | 0.575a | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| FACT-M | PWB | 0.464 | 0.478 | 0.418 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| SWB | 0.343 | 0.376 | 0.166 | 0.180 | 1 | NA | NA | NA | |

| EWB | 0.432 | 0.505a | 0.158 | 0.500 | 0.264 | 1 | NA | NA | |

| FWB | 0.460 | 0.440 | 0.402 | 0.431 | 0.530a | 0.353 | 1 | NA | |

| Total | 0.570a | 0.608a | 0.422 | 0.652a | 0.682a | 0.607a | 0.794a | 1a | |

Abbreviations: AQoL-8D indicates the Assessment of Quality of Life–8-Dimension scale; EWB, emotional well-being; FACT-M, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Melanoma scale; FWB, functional well-being; MSD, mental super dimension; NA, not applicable; PSD, physical super dimension; and PWB, physical well-being; SWB, social well-being.

Strong correlation.

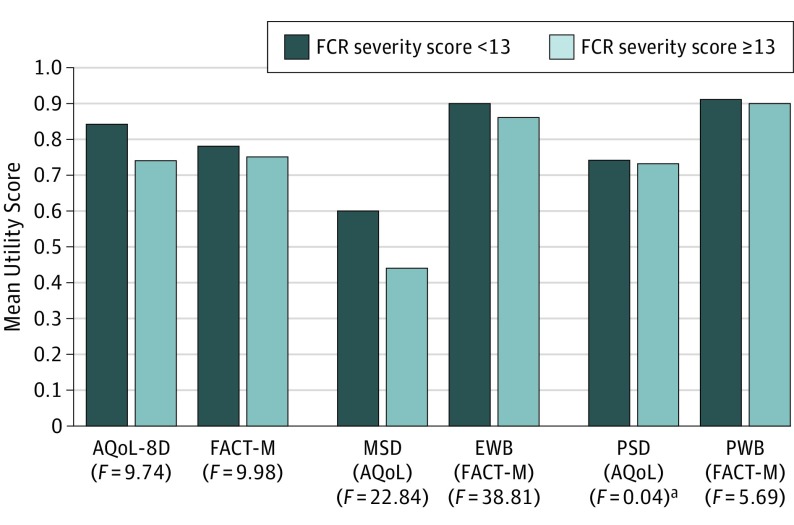

eTable 1 in the Supplement summarizes the results of the responsiveness analysis. We found that 0.6% of AQoL-8D responses (n = 1) and 0% of FACT-M responses (n = 0) indicated a maximum utility of 1 (full health). A proportion of 3.7% of AQol-8D responses (n = 6) and 0% of FACT-M responses (n = 0) indicated very low health, with a utility between 0.0 and 0.2. The AQoL-8D had a much larger utility range than did the FACT-M. The AQoL-8D physical super dimension identified 7.3% of responses (n = 12) in full health, while the mental super dimension identified very low health on 10.4% of responses (n = 17). The AQoL-8D and FACT-M both exhibited differences between FCRI level (F1,161 = 9.74, P = .002 for the AQoL-8D and F1,161 = 9.98, P = .002 for the FACT-M) (Figure 2). The physical super dimension of the AQoL-8D showed no difference between the groups (F1,161 = 0.04, P = .84) compared with the physical well-being component of the FACT-M (F1,161 = 5.69, P = .02). The mental health dimension of the AQoL-8D showed a significant difference between the groups (F1,161 = 22.84, P < .001) as did the emotional well-being dimension of the FACT-M (F1,161 = 38.81, P < .001).

Figure 2. Scores for AQoL-8D and FACT-M Instruments by FCR Group (Convergent Validity).

Health-related quality-of-life instrument scores by participant self-reported fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) severity score. AQoL-8D indicates the Assessment of Quality of Life–8-Dimension scale; EWB, emotional well-being; FACT-M, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Melanoma scale; MSD, mental super dimension; PSD, physical super dimension; and PWB, physical well-being. The F statistic reports the statistical significance of the strength of relationship between model predictors and the response variable, significance level 5%.

aNot statistically significant at the 5% level.

FCR Severity and HRQOL

The AQoL-8D mean (SD) utility scores were 0.84 (0.18) for the normal FCR group and 0.74 (0.21) for the high FCR group (P = .002) (Table 3). The FACT-M mean (SD) utility scores were 0.78 (0.05) for the normal FCR group and 0.75 (0.08) for the high FCR group (P = .002). The incremental change in scores of the 2 HRQOL instruments with an increase in FCR severity was examined using multiple stepwise regression models (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Participants who reported high FCR reported AQoL-8D scores that were 0.12 units lower than participants who reported normal FCR. Those with a higher melanoma stage (ie, stage II) reported higher AQoL-8D utility scores. Those who lived in rural or regional areas reported lower HRQOL scores with the AQoL-8D instrument compared with participants who lived in metropolitan areas. To a lesser extent, results for the FACT-M showed a lower utility (−0.035) for people with high FCR and a lower utility among those who were married. The results obtained through stepwise vs simultaneous entry regression (data not reported) were similar.

Table 3. FACT-M and AQoL-8D Utilities by Demographic and Melanoma Characteristics.

| Subgroup | FACT-M Utility | AQoL-8D Utility | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, No. | Mean (SD) | P Value | Patients, No. | Score, Mean (SD) | P Value | |

| Sex | .40 | .20 | ||||

| Male | 91 | 0.76 (0.07) | 92 | 0.79 (0.20) | ||

| Female | 72 | 0.76 (0.07) | 71 | 0.75 (0.21) | ||

| Median age, y | .20 | .27 | ||||

| ≤59 | 84 | 0.75 (0.08) | 84 | 0.76 (0.20) | ||

| >59 | 79 | 0.77 (0.06) | 79 | 0.79 (0.20) | ||

| Area of residence | .87 | .03a | ||||

| Metropolitan | 55 | 0.76 (0.07) | 109 | 0.73 (0.25) | ||

| Rural/regional | 108 | 0.76 (0.07) | 54 | 0.80 (0.18) | ||

| Time since last melanoma diagnosis, y | .71 | .46 | ||||

| ≤5 | 65 | 0.76 (0.07) | 66 | 0.79 (0.19) | ||

| >5 | 93 | 0.76 (0.07) | 92 | 0.76 (0.22) | ||

| Marital status | .04a | .65 | ||||

| Married | 139 | 0.77 (0.06) | 139 | 0.78 (0.20) | ||

| Other | 24 | 0.76 (0.11) | 24 | 0.76 (0.23) | ||

| Highest education level completed | .18 | .71 | ||||

| No university degree | 100 | 0.75 (0.07) | 100 | 0.77 (0.21) | ||

| University degree | 62 | 0.77 (0.06) | 62 | 0.78 (0.20) | ||

| AJCC stage | .35 | .01a | ||||

| 0/Ib | 100 | 0.76 (0.07) | 101 | 0.74 (0.23) | ||

| II | 53 | 0.77 (0.07) | 52 | 0.83 (0.14) | ||

| Melanomas, No. | .08 | .40 | ||||

| ≤5 | 62 | 0.77 (0.06) | 63 | 0.79 (0.20) | ||

| 6-10 | 101 | 0.75 (0.07) | 100 | 0.76 (0.21) | ||

| Health literacy | .30 | .61 | ||||

| No use of surrogate reader | 152 | 0.76 (0.07) | 152 | 0.77 (0.21) | ||

| Use of surrogate reader | 11 | 0.74 (0.08) | 11 | 0.81 (0.17) | ||

| FCRI severity | .002a | .002a | ||||

| ≤13 | 54 | 0.78 (0.05) | 54 | 0.84 (0.18) | ||

| >13 | 109 | 0.75 (0.08) | 109 | 0.74 (0.21) | ||

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Cancer Committee; FCRI, Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory.

Significant finding.

Owing to the small number of participants with stage 0 melanoma, stage 0 and I were combined in the analysis.

Discussion

Use of an HRQOL utility index is critical to cost-utility analyses of health care interventions. This study purposefully assessed HRQOL to determine, in the context of an RCT, intervention-specific responsiveness and subsequent cost utility. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare utility scores derived from the AQoL-8D and FACT-M instruments for people with melanoma. Utility scores from both instruments were moderately to highly correlated, and mean scores were similar. Score distributions, however, were somewhat different; FACT-M utility scores followed a relatively normal distribution, unlike AQoL-8D scores, which were negatively skewed. This could signify that the 2 instruments were measuring different constructs or different aspects of the same construct. For 10% of participants (n = 17), the AQoL-8D identified problems on the mental health dimension, whereas the FACT-M detected none. This might indicate issues with content validity; further qualitative analysis is needed to clarify this. However, both instruments were able to discriminate between subgroups of interest, particularly in relation to FCR (higher FCR severity scores were associated with lower utilities for both instruments).

Relationship Between HRQOL and FCR

Fear of cancer recurrence has been identified as an important symptom of distress reported by melanoma survivors, and elevated FCR has been found to be associated with lower quality of life and impaired social and emotional functioning. In this study, both HRQOL instruments identified a decrement in scores with an increase in FCR severity; however, regression analyses revealed a greater decrement (3 times greater) using the AQoL-8D compared with the FACT-M. This could be attributed, at least in part, to the variability in emphasis placed on the subdomains of the 2 instruments. The AQoL-8D was designed to be sensitive to self-reported changes in mental health, whereas the FACT-M was intended to focus on self-reported changes in physical functioning. This finding, as first suggested by Morton, confirms the AQoL-8D as an alternative (and potentially preferable) instrument for assessing HRQOL and utility in clinical trials and economic evaluations of psychological interventions for people with melanoma, as it is likely to be more sensitive to changes in psychological health.

Implications for Future Research

The AQoL-8D is an instrument designed to assess physical and mental health, and it therefore has the potential to broaden the evaluative spectrum of economic evaluations in psychological care by focusing on more than physical health alone. This is a particularly useful property for populations such as those in specialized cancer surveillance programs who may experience important psychological challenges. In addition, in the present study, the AQoL-8D demonstrated a capacity to discriminate between different patient subgroups, such as those with high vs normal FCR severity and those living in a city vs a rural or regional setting. Based on these results, we recommend use of the AQoL-8D instrument for economic evaluations of psychological care.

From a clinical perspective, it is important for clinicians such as dermatologists, surgeons, and general practitioners to use sensitive and easy-to-administer instruments to identify patients who may be experiencing difficulties and to develop specific protocols to provide tailored supportive care strategies. Previous research has shown that the availability of additional support, such as the opportunity for patients to discuss fears and anxieties with clinical staff in a supportive environment, and guidance in developing coping strategies, are important for enhancing emotional health and well-being.

The clinical usefulness of the HRQOL instrument is determined by its validity and responsiveness and also by its practicality (ie, simple, quick to complete, easy to score, and provides useful clinical data). Although we did not formally assess the acceptability of use, we found that participants were willing to undertake the assessments of HRQOL using both the AQoL-8D and FACT-M. We noted a high rate of questionnaire completion, particularly for those opting for the online version. However, outside of a trial, we would likely recommend the use of a single valid and relevant instrument.

In addition to the requisite characteristics of any HRQOL instrument in research, such as validity and reliability, in clinical practice a wider range of properties such as responsiveness to clinical change and interpretability are required to ensure the usability of the tool. In this study, both instruments were shown to be sensitive to FCR, with the AQoL-8D being more responsive to changes in psychological aspects of health. This is a useful property to assess health in high-risk cancer populations of individuals who may face important psychological distress.

To achieve better health outcomes, several government initiatives have moved toward a system of assessing clinical care based on quality (and value) rather than quantity of care. One component of this quality framework includes incorporating patient-reported outcomes such as quality-of-life measures into standard clinical practice to improve communication between patients and their clinicians.

Limitations

Some potential limitations of our study should be noted. First, the mapping function used in this study was developed for mapping the EQ-5D to the FACT-M. Although the AQoL-8D and the EQ-5D both assess related HRQOL domains, the mechanisms for deriving and interpreting utility scores from each instrument are different. Therefore, caution should be observed for the interpretation of the derived utility, which should be used only for group-level analysis and not for individual clinical decisions.

Second, the choice of the cutoff point for FCR used in the convergent validity analysis should be interpreted with caution. While this cutoff point is currently the best available to identify high or clinical FCR, it may not provide an accurate indication of high FCR. It may also signal the need for more complex analyses to better understand the point at which FCR negatively influences functioning and well-being for people with a history of melanoma. Added to this are the methodological limitations in dichotomizing naturally continuous variables such as loss of information about individual differences and loss of effect size and power.

Third, this study was based on scores provided at a single time point, so a thorough comparison of the responsiveness of the 2 instruments to change over time was not assessed. In the RCT that generated the data for this study, our group found no significant effect of the intervention on HRQOL at 6 months, when assessed with either the AQoL-8D or FACT-M, despite observing a significant reduction in FCR severity scores. This may be explained by several factors: (1) the intervention in the RCT was designed primarily to improve the specific outcome of FCR rather than the more general HRQOL; (2) fewer participants in the RCT completed the responses for the quality-of-life measure than for the FCRI at 6 months; (3) continuous rather than categorical measures were used for FCR in the present analysis (ie, a change in mean score at 6 months compared with the number above a cutpoint); and (4) FCR scores were adjusted in the present analysis at 6 months for scores at 1 month (when the largest effect was observed), and that adjustment was not performed for the HRQOL scores.

Finally, use of the FACT-M with people who had a history of early-stage cancer can be controversial. Since most people diagnosed with early-stage melanoma will likely experience few limitations in their physical functioning and be more likely to be affected emotionally, the content of the FACT-M has been targeted to people with advanced melanoma.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that both the AQoL-8D and the FACT-M are sensitive measures for capturing utility-based quality of life in people with melanoma. Both instruments appear to differentiate between different patient subgroups, with the AQoL-8D demonstrating stronger discriminative capacity. Lower HRQOL assessed using both the AQoL-8D and FACT-M was associated with greater FCR severity, and a larger decrement was observed with the AQoL-8D. For economic evaluations of psychological interventions for people with melanoma, the AQoL-8D is a valid and sensitive measure that can be used to assess utility-based health states. If the relationship between quality of life and FCR is causal, then the loss of utility attributable to FCR is an important issue, signaling a need for interventions to reduce FCR. The findings of this study will enable researchers to calculate cost utility using FCR for interventions where utility measures were not empirically collected.

eAppendix. Instrument description

eTable 1. Floor and ceiling effect analysis for the sub domains of the two

instruments

eTable 2. Stepwise multivariate linear regressions with backward selection of

AQoL-8D and FACT-M upon FCR levels

References

- 1.de Vries E, Coebergh JW. Cutaneous malignant melanoma in Europe. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40(16):2355-2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costa DS, Dieng M, Cust AE, Butow PN, Kasparian NA. Psychometric properties of the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory: an item response theory approach. Psychooncology. 2016;25(7):832-838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thewes B, Butow P, Zachariae R, Christensen S, Simard S, Gotay C. Fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic literature review of self-report measures. Psychooncology. 2012;21(6):571-587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasparian NA, McLoone JK, Butow PN. Psychological responses and coping strategies among patients with malignant melanoma: a systematic review of the literature. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145(12):1415-1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibertini M, Reintgen DS, Baile WF. Psychosocial aspects of melanoma. Ann Plast Surg. 1992;28(1):17-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10(1):19-28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hodges LJ, Humphris GM. Fear of recurrence and psychological distress in head and neck cancer patients and their careers. Psychooncology. 2009;18(8):841-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mast ME. Survivors of breast cancer: illness uncertainty, positive reappraisal, and emotional distress. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1998;25(3):555-562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deimling GT, Bowman KF, Sterns S, Wagner LJ, Kahana B. Cancer-related health worries and psychological distress among older adult, long-term cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2006;15(4):306-320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphris GM, Rogers S, McNally D, Lee-Jones C, Brown J, Vaughan D. Fear of recurrence and possible cases of anxiety and depression in orofacial cancer patients. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32(5):486-491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mirabeau-Beale KL, Kornblith AB, Penson RT, et al. Comparison of the quality of life of early and advanced stage ovarian cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114(2):353-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):300-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570-579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang SB, Askew RL, Xing Y, et al. Prospective assessment of postoperative complications and associated costs following inguinal lymph node dissection (ILND) in melanoma patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(10):2764-2772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Winstanley JB, White EG, Boyle FM, Thompson JF. What are the pertinent quality-of-life issues for melanoma cancer patients? Aiming for the development of a new module to accompany the EORTC core questionnaire. Melanoma Res. 2013;23(2):167-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morton RL. Essential inputs for studies of cost-effectiveness analysis in melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(6):1294-1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richardson J, Iezzi A, Khan MA, Maxwell A. Validity and reliability of the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL)-8D multi-attribute utility instrument. Patient. 2014;7(1):85-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dieng M, Butow PN, Costa DS, et al. Psychoeducational intervention to reduce fear of cancer recurrence in people at high risk of developing another primary melanoma: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(36):4405-4414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simard S, Savard J. Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory: development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(3):241-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Askew RL, Swartz RJ, Xing Y, et al. Mapping FACT-melanoma quality-of-life scores to EQ-5D health utility weights. Value Health. 2011;14(6):900-906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowen D, Young T, Brazier J, Gaugris S. Comparison of generic, condition-specific, and mapped health state utility values for multiple myeloma cancer. Value Health. 2012;15(8):1059-1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simard S, Savard J. Screening and comorbidity of clinical levels of fear of cancer recurrence. J Cancer Surviv. 2015;9(3):481-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16(3):297-334. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cortina JM. What is coefficient alpha: an examination of theory and applications. J Appl Psychol. 1993;78(1):98-104. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winstanley JB, Saw R, Boyle F, Thompson J. The FACT-Melanoma quality-of-life instrument: comparison of a five-point and four-point response scale using the Rasch measurement model. Melanoma Res. 2013;23(1):61-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thornicroft G, Slade M. Are routine outcome measures feasible in mental health? Qual Health Care. 2000;9(2):84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higginson IJ, Carr AJ. Measuring quality of life: Using quality of life measures in the clinical setting. BMJ. 2001;322(7297):1297-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Department of Health and Human Services Better, smarter, healthier: in historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value [January 26, 2015 press release].

- 30.Lebel S, Ozakinci G, Humphris G, et al. Current state and future prospects of research on fear of cancer recurrence. Psychooncology. 2017;26(4):424-427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.MacCallum RC, Zhang S, Preacher KJ, Rucker DD. On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychol Methods. 2002;7(1):19-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cornish D, Holterhues C, van de Poll-Franse LV, Coebergh JW, Nijsten T. A systematic review of health-related quality of life in cutaneous melanoma. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(suppl 6):vi51-vi58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix. Instrument description

eTable 1. Floor and ceiling effect analysis for the sub domains of the two

instruments

eTable 2. Stepwise multivariate linear regressions with backward selection of

AQoL-8D and FACT-M upon FCR levels