Key Points

Question

Which dermatology-related services are independently billed by nonphysician clinicians (NPCs) treating Medicare beneficiaries, and where are these clinicians located?

Findings

Nonphysician clinicians independently billed for a wide variety of services including complex procedures. Most NPCs were in US counties with high physician densities.

Meaning

The number and types of services independently performed by NPCs will likely continue to grow; further study of NPC training and integration with the dermatology discipline is an important part of addressing the changing US dermatology workforce.

This study uses Medicare and US Census data to discover which dermatology-related services are independently billed by nonphysician clinicians treating Medicare beneficiaries, and where these clinicians are located.

Abstract

Importance

Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) are nonphysician clinicians (NPCs) who can deliver dermatology services. Many of these services are provided independently. Little is known about the types of services provided or where NPCs provide independent care.

Objective

To examine characteristics of dermatology care for Medicare enrollees billed independently by NPCs.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Retrospective review of the 2014 Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data: Physician and Other Supplier Public Use File, which reflects fee-for-service payments to clinicians for services rendered to Medicare beneficiaries. Clinician location was matched with county-level demographic data from the American Community Survey, US Census Bureau. Clinicians identified using National Provider Identifier as NPs or PAs with at least 11 claims for common dermatology-associated Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System procedure codes were included.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Total services provided by service type category, density of dermatologists and nondermatologists who perform dermatology-related services, and geographic location by county.

Results

Among the cohort of NPCs were 824 NPs (770 [93.5%] female) and 2083 PAs (1602 [76.9%] female) who independently billed Medicare $59 438 802 and $171 645 943, respectively. Dermatologists were affiliated with 2667 (92%) independently billing NPCs. Most payments were for non–evaluation and management services including destruction of premalignant lesions, biopsies, excisions of skin cancer, surgical repairs, flaps/grafts, and interpretation of pathologic analysis. Nurse practitioners and PAs billed for a similar distribution of service categories overall. A total of 2062 (70.9%) NPCs practiced in counties with dermatologist density of greater than 4 per 100 000 population. Only 3.0% (86) of independently billing NPCs practiced in counties without a dermatologist. Both dermatologists and NPCs were less likely to be in rural counties than in urban counties.

Conclusions and Relevance

Nonphysician clinicians independently billed for a wide variety of complex dermatologic procedures. Most independently billing NPCs practice in counties with higher dermatologist densities, and nearly all these NPCs were affiliated with dermatologists. Further study of NPC training and integration with the dermatology discipline is an important part of addressing the changing US dermatology workforce.

Introduction

The demand for dermatologists’ services continues to increase, particularly because of the epidemic of skin cancer. Despite the increase in demand, the number of dermatologists produced each year remains relatively static. Consequently, a limited number of dermatologists are relied on to care for a growing, aging population. As a result, there has been an increasing reliance on nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs), together referred to as nonphysician clinicians (NPCs), to fill the void. This phenomenon is not unique to dermatology, as many other medical specialties have had to grapple with meeting projected increasing demand for health care services. According to the Association of American Medical Colleges, the estimated physician shortage will be between 46 100 to 90 400 physicians (or clinicians) by 2025. However, other analyses suggest that supply is adequate and distribution may be a more pressing issue. Increasing the number and use of NPCs has been proposed as a possible solution for physician shortages and maldistribution, including within dermatology. While the original intent of NPCs was to provide expanded access to primary care, it is becoming increasingly common for NPCs to offer specialty care services. In fact, the proportion of PAs reporting primary care practice has steadily decreased from 50% in 1997 to 30% in 2013. This phenomenon is similar among physicians: in 2010 only approximately 16% to 18% of medical students were likely to practice primary care.

In dermatology, nearly half of practices employ NPCs who perform both medical and procedural services. A majority of procedural services independently billed by NPCs for Medicare beneficiaries were in the specialty area of dermatology. Supervision and training of NPCs in dermatology practice continues to be a contested issue with no clear consensus about the appropriate breadth in scope of practice. Although NPs and PAs can perform similar duties, their scope of practice differs by state. While NPs can practice with full independence in 22 states and the District of Columbia, PAs must practice under the supervision of a physician. However, when it comes to billing Medicare, both NPs and PAs can bill independently under their own National Provider Identifier (NPI) depending on the clinical scenario. When PAs and NPs bill under their own NPI, they are reimbursed at 85% of the Medicare contracted rate. To receive 100% of the Medicare contracted rate, a supervising physician must physically see any new patient or any established patient with a new medical problem. Nurse practitioners and PAs can still receive 100% of the Medicare contracted rate for established patients with the identical original problems, as long as a supervising physician is physically on location. This is known as “incident-to” billing as delineated in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997.

As the number of practicing NPCs increases and the dermatology workforce continues to change, it will be important to understand the patterns of dermatology services delivered to Medicare beneficiaries by NPCs. This study examines delivery of dermatology care by NPCs for Medicare beneficiaries. It also examines the density of dermatologists and NPCs who independently bill for dermatology-related services, as well as the relationship to rurality.

Methods

Payment Data Set

The 2014 Medicare Physician and Other Supplier Public Use File (POSPUF) was used for this analysis (January 1, 2014, through December 31, 2014). It contains Medicare Part B noninstitutional claims for services and procedures delivered in office-based settings by physicians and NPCs. The database captures Medicare payments and submitted charges delineated by a combination of NPI number, Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) code, and place of service. Clinician specialty, sex, and other information are also reported. Data are aggregated at the clinician and HCPCS code level, excluding aggregated records with 10 or fewer beneficiaries to protect the privacy of Medicare beneficiaries. This study was exempt from institutional review board review because only publicly available data sources were used.

Payments

Clinician payments were defined as the mean Medicare allowed amount for each service (HCPCS code) delivered by each NPC for all patients at a particular practice location. The Medicare allowed amount is the sum of payments by Medicare, the beneficiary, and any amount paid by a third party (eg, supplemental insurance, Medicaid). Total payments were grouped by service as follows: evaluation and management, biopsy, shave removal, destruction benign, destruction malignant, destruction premalignant, benign excision, malignant excision, flaps/grafts, repair, pathologic analysis, Mohs layer(s), and other, which aggregated services such as injection (eg, triamcinolone, prednisolone), potassium hydroxide preparation, and blood sampling. For evaluation and management, we chose to focus our analysis on new or established outpatient visits (HCPCS 99201-99215) because these are the most frequently used in dermatology.

NPC Cohort Criteria

Nonphysician clinicians were identified by only including clinicians who indicated “nurse practitioner” or “physician assistant” as their primary specialty practice on their Part B claims. Our analysis was restricted to NPCs who had at least 11 instances of the following dermatology-associated HCPCS procedures: destruction of premalignant lesions, skin biopsy, excision of malignant lesion, destruction of malignant lesion, or repair. These particular procedures were selected because they reflect the most common and/or specific procedures performed by dermatologists in POSPUF. To increase the likelihood of including only NPCs who work with dermatologists, the cohort was further restricted to exclude all NPCs with codes not typically associated with dermatology practice such as electrocardiography, pulmonary function testing, Papanicolaou testing, as well as nursing home and hospital visits. Given that it was not possible in the Medicare data to link NPCs to specific physicians to determine specialty association, we conducted Google searches to identify which NPCs worked with board-certified dermatologists.

Density Mapping

Maps were generated using ArcGIS software, version 10.2.1 (Esri). Clinicians were aggregated by zip code from the POSPUF file. County-level demographic data were obtained from the 2010 to 2014, 5-year estimates of the American Community Survey, which is supported by the United States Census Bureau. Counties were classified as rural or urban based on the National Center for Health Statistics Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. Micropolitan and noncore counties were considered rural counties. Large central metropolitan, large fringe metropolitan, medium metropolitan, and small metropolitan were all considered urban counties. Densities of dermatologists and NPCs were calculated per 100 000 persons per county.

Statistical Analysis

Mean payments by service category and the relative use of services across clinicians in 2014 were summarized. Wilcoxon 2-sample tests were used to test differences in proportion of clinicians by rurality. All statistical tests were 2-sided with P < .05 as the level of significance. Analyses were performed using STATA 14 and SAS 9.4.

Results

There were 938 147 unique clinicians who billed Medicare in 2014. Of that number, 10 957 (1.2%) were dermatologists, 68 420 (7.3%) were NPs, and 49 270 (5.3%) were PAs. Multiple physician disciplines provided a variety of dermatology-related services, and NPCs independently billed for many dermatology-related services, most notably destruction of premalignant lesions, destruction of benign lesions, and biopsies (eTable 1 in the Supplement).

After restriction to NPCs with at least 11 instances of dermatology-associated procedures, the numbers of NPCs were reduced to 824 NPs and 2083 PAs, representing 1.2% and 2.2% of these total clinicians, respectively. The total cost of services was $59 438 802 for NPs and $171 645 943 for PAs. Most payments were for non–evaluation and management services. Although PAs outnumbered NPs, they billed for similar proportions of service categories overall (Table 1 and Table 2). Nurse practitioners billed independently most frequently for evaluation and management, followed by destruction of premalignant lesions, destruction of benign lesions, and biopsies. Among PAs, biopsies were more commonly billed than destruction of benign lesions. A minority of NPCs also independently billed for a substantial number of more complex procedures such as evaluation of pathologic analysis (16 038), excision of malignant lesions (16 727), repairs (25 491), flaps, and grafts (2749). However, most of the NPCs independently billing for these procedures were associated with dermatologists.

Table 1. Services, Procedures, and Costs for Nurse Practitioners.

| Procedure | Total Payment, $ | Percentage of Total Payment | Clinicians Receiving Payment, % | Affiliated With Dermatologist, No. (%) | Payment per Procedure, Mean (SD), $ | No. of Procedures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | IQR | Maximum | Total | ||||||

| Total | 59 438 802 | 824 | 725 (88) | ||||||

| E/M new | 5 535 794 | 9.3 | 708 (86) | 636 (90) | 72.40 (22.39) | 64 (60) | 23-82 | 453 | 76 912 |

| E/M established | 22 118 702 | 37.2 | 814 (99) | 716 (88) | 57.80 (21.31) | 201 (261) | 42-254 | 2702 | 381 716 |

| Destruction premalignant | 15 913 308 | 26.8 | 789 (96) | 708 (90) | 56.70 (56.14) | 351 (617) | 46-394 | 7092 | 722 708 |

| Biopsy | 9 619 801 | 16.2 | 731 (89) | 660 (90) | 58.01 (28.47) | 112 (136) | 28-142 | 1110 | 152 632 |

| Repair | 1 095 904 | 1.8 | 86 (10) | 81 (94) | 261.21 (69.06) | 29 (28) | 15-32 | 196 | 4187 |

| Pathology | 134 770 | 0.2 | 22 (3) | 19 (86) | 35.63 (12.92) | 180 (304) | 24-101 | 1289 | 4492 |

| Flaps/grafts | 291 131 | 0.5 | 4 (<0.1) | 4 (100) | 764.02 (96.05) | 33 (26) | 14-46 | 96 | 393 |

| Destruction benign | 5 304 348 | 8.9 | 612 (74) | 573 (94) | 87.42 (11.48) | 88 (98) | 26-114 | 775 | 60 890 |

| Destruction malignant | 1 105 256 | 1.9 | 138 (17) | 133 (96) | 126.47 (30.05) | 29 (25) | 15-32 | 224 | 8799 |

| Malignant excision | 416 216 | 0.7 | 68 (8) | 64 (94) | 140.25 (40.45) | 26 (18) | 14-29 | 105 | 3035 |

| Shave removal | 1 498 488 | 2.5 | 141 (17) | 129 (91) | 75.67 (22.46) | 46 (75) | 16-45 | 785 | 20 854 |

| Benign excision | 308 940 | 0.5 | 132 (16) | 121 (92) | 69.72 (24.25) | 25 (22) | 14-28 | 213 | 4300 |

| Othera | 1 631 938 | 2.7 | 323 (39) | 270 (84) | 32.72 (51.13) | 105 (722) | 19-76 | 21 000 | 95 455 |

Abbreviations: E/M, evaluation and management; IQR, interquartile range.

Aggregated services such as injection (eg, triamcinolone, prednisolone), potassium hydroxide preparation, and blood sampling.

Table 2. Services, Procedures, and Costs for Physician Assistants.

| Procedure | Total Payment, $ | Percentage of Total Payment | Clinicians Receiving Payment, % | Affiliated With Dermatologist, No. (%) | Payment per Procedure, Mean (SD), $ | No. of Procedures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | IQR | Maximum | Total | ||||||

| Total | 171 645 943 | 2083 | 1942 (93) | ||||||

| E/M new | 14 721 086 | 8.6 | 1801 (86) | 1704 (95) | 72.89 (21.53) | 65 (67) | 22-82 | 660 | 204 177 |

| E/M established | 54 681 432 | 31.9 | 2057 (99) | 1920 (93) | 59.02 (21.44) | 194 (252) | 41-242 | 3453 | 931 031 |

| Destruction premalignant | 42 996 967 | 25.0 | 2021 (97) | 1895 (94) | 58.12 (56.47) | 361 (626) | 44-395 | 9755 | 1 926 710 |

| Biopsy | 26 267 284 | 15.3 | 1924 (92) | 1819 (95) | 58.54 (26.72) | 114 (170) | 28-141 | 5293 | 416 433 |

| Repair | 5 869 214 | 3.4 | 346 (17) | 330 (95) | 261.18 (75.91) | 33 (39) | 14-36 | 639 | 21 304 |

| Pathology | 450 051 | 0.3 | 71 (3) | 68 (96) | 39.15 (14.52) | 146 (187) | 31-218 | 1138 | 11 546 |

| Flaps/grafts | 1 683 049 | 1.0 | 14 (1) | 14 (100) | 715.57 (100.21) | 39 (36) | 15-44 | 154 | 2356 |

| Destruction benign | 13 707 364 | 8.0 | 1582 (76) | 1503 (95) | 89.17 (11.30) | 87 (100) | 24-110 | 1293 | 155 575 |

| Destruction malignant | 3 478 949 | 2.0 | 468 (22) | 457 (98) | 125.54 (23.35) | 28 (23) | 15-31 | 371 | 28 093 |

| Malignant excision | 1 825 294 | 1.1 | 248 (12) | 237 (96) | 132.34 (44.21) | 29 (31) | 15-31 | 308 | 13 692 |

| Shave removal | 3 194 564 | 1.9 | 315 (15) | 298 (95) | 79.09 (20.95) | 42 (86) | 16-40 | 1403 | 41 429 |

| Benign excision | 634 876 | 0.4 | 297 (14) | 279 (94) | 69.12 (24.05) | 24 (23) | 14-27 | 335 | 9107 |

| Othera | 2 135 812 | 1.2 | 757 (36) | 697 (92) | 26.27 (37.62) | 65 (135) | 18-56 | 2694 | 123 904 |

Abbreviations: E/M, evaluation and management; IQR, interquartile range.

Aggregated services such as injection (eg, triamcinolone, prednisolone), potassium hydroxide preparation, and blood sampling.

Of the total number of NPCs (2907), 2667 (92%) were associated with dermatologists, 161 (6%) with nondermatologists (mostly family medicine and plastic surgery), 21 (<1%) were independently practicing, and 54 (2%) had an unknown affiliation (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

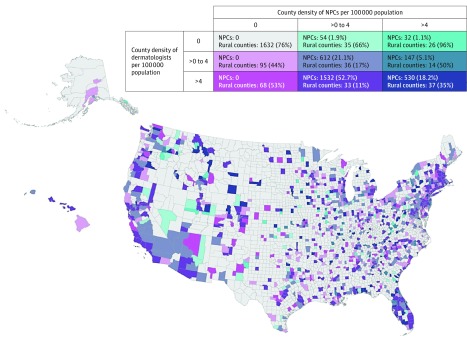

The Figure is a bivariate map demonstrating the density of dermatologists and NPCs in our cohort within each county in the United States. Most counties (2158 [67%]) do not have a dermatologist or an NPC delivering independent services. The highest densities of dermatologists were located on the West Coast, portions of the East Coast, in clusters in the Midwest, and in Florida. The distribution of NPCs and dermatologists were similar (eFigures 1 and 2 in the Supplement).

Figure. US Dermatologists and Nonphysician Clinicians by County.

Bivariate map of the density of dermatologists and density of independently billing nonphysician clinicians (NPCs) (N = 2907) per 100 000 people in each county who deliver dermatology-related services and procedures.

The majority (2062 [70.9%]) of NPCs were in counties that have a density of dermatologists greater than 4 per 100 000 population. A small proportion of counties have an independently billing NPC and no dermatologist (86 [3.0%]). When the density of NPCs is higher than that of dermatologists within a county, that county is more likely to be rural (Figure). The mean (SD) density of dermatologists per county was higher in urban counties (2.28 [3.75] per 100 000 population) than in rural counties (0.55 [1.80] per 100 000 population). Similarly, the mean (SD) density of NPCs was 0.79 (1.46) per 100 000 in urban counties vs 0.36 (1.67) per 100 000 in rural counties. Tests of differences in medians indicated statistically significant differences in densities of NPCs and dermatologists between rural and urban counties (Table 3).

Table 3. Urban vs Rural Rates of Dermatologists and Nonphysician Clinicians per 100 000 Population.

| County Type | Rate per 100 000 Population | P Value for Difference in Medians | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Range) | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Dermatologists | ||||

| Rural (n = 1976 counties) | (0-24.91) | 0.55 (1.80) | 0 (0-0) | <.001 |

| Urban (n = 1245 counties) | (0-70.37) | 2.28 (3.75) | 1.15 (0-3.65) | |

| Nonphysician clinicians | ||||

| Rural (n = 1976 counties) | (0-39.54) | 0.36 (1.67) | 0 (0-0) | <.001 |

| Urban (n = 1245 counties) | (0-15.25) | 0.79 (1.46) | 0 (0-1.17) | |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

Discussion

As previously reported, NPCs independently bill Medicare for a broad scope of dermatology-associated services. In the present study, the most frequent services were evaluation and management, destruction of premalignant lesions, skin biopsy, and destruction of benign lesions. However, many NPCs bill independently for more complex services including intermediate/complex repairs on high-risk areas on the head and neck, flaps/grafts, and gross/microscopic examination of surgical pathologic analysis. Most of these complex services are provided by NPCs associated with dermatologists.

Nonphysician clinicians have become part of nearly every specialty in medicine. These clinicians can perform a broad range of health care services traditionally performed by physicians and, if billed independently, at lower a rate of reimbursement. With the current shortage of physicians and the push to decrease health care costs, the numbers of NPCs can be expected to continue to increase in all areas of health care. Nearly half of dermatology practices employ NPCs, and many services can be billed independently by NPCs. The only common dermatology-associated procedure not billed by NPCs is Mohs surgery, which can only be billed by a physician, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

Independent billing does not necessarily suggest that a physician was unavailable for immediate consultation by an NPC; however, it does suggest that a physician had limited involvement in a patient’s care. It is difficult to assess quality of care by clinician type on a population level because there is no mandatory reporting requirement for complications by NPCs and quality measures in dermatology have been difficult to generate. There is evidence that the quality of care provided by NPCs is similar to that of physicians within other specialties. However, a study showed that the number needed to biopsy of any skin cancer was double for NPCs than for dermatologists. Similarly, elevated number-needed-to-biopsy ratios have also been seen in physicians without dermatology training. Another study noted an increase in malpractice claims associated with cosmetic laser surgery by NPCs; however, overall most of the cases (57.2%) involved a physician, and the study could not ascertain the training level of the nonphysician laser operator. Indeed, there are opportunities to prospectively collect data on quality of care. Training and collaborative supervision may improve outcomes. Perhaps requiring achievement of certain minimum standards for certain procedures akin to those set for residents by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education could be useful.

Related to access to care, this study shows that most dermatologists and NPCs favor practicing in urban counties. It is noteworthy that counties with a higher density of NPCs than dermatologists were mostly rural. Thus, to provide valuable dermatology care throughout the country, especially for rural areas that have traditionally been underserved by dermatologists, dedicated dermatology training for NPCs may be helpful. Currently, the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants, the nation’s only certifying organization for PAs, does not have a specialty certification in dermatology. There are also no accredited subspecialty training programs for NPs; however, the Dermatology Nurses’ Association does offer a certification examination. Formal NPC dermatology training, including testing, supervisions of services and procedures, surgical logs, and surgical case minimums may help avoid the possible challenges noted herein, related to laser complications and diagnostic uncertainty (ie, number needed to biopsy).

Limitations

The results of this study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. There are no patient-level data in POSPUF; thus, it is not possible to determine the propriety or quality of the services rendered. We captured 2083 PAs in our cohort, which is less than the figure of 2520 from 2016 released by the Society of Dermatology Physician Assistants, who represent more than 75% of all US dermatology PAs. Our study was limited to NPCs who billed for a specific subset of HCPCS services and may not capture NPCs who care for dermatology patients and provide no procedural services. Additionally, it was not possible to capture NPCs who bill Medicare under a supervising physician’s NPI. These data only include clinicians who care for Medicare beneficiaries. Nonphysician clinicians see patients with a variety of different types of insurance. Also, our internet searches occurred in 2017, while the Medicare data are from 2014. It is possible that some NPCs previously practiced in different settings, which could have led to misclassification; however, this only affected a minority of individuals, of whom many had accessible, searchable workplace histories that decreased this potential error and would not have altered our overall conclusions.

Given the increase in the number of Medicare beneficiaries, the number of services independently performed by NPCs will likely increase in the future. Studying NPC training and integration into dermatology will be an important part of the changing landscape of the dermatology health care workforce.

Conclusions

Nurse practitioners and PAs provide a variety of dermatologic procedures to Medicare beneficiaries and bill for them independently. A majority of NPCs who perform dermatology-related procedures are affiliated with dermatologists. This trend may grow over time with an increase in the number of Medicare beneficiaries. Both NPCs and dermatologists are less likely to practice in rural counties. Most independently billing NPCs practice in counties with higher physician density. Further study of NPC training and integration with the dermatology specialty is an important part of addressing dermatology care across the country.

eTable 1. Number and proportion of services and dermatology-related procedures by clinician type

eFigure 1. Map of the density of US dermatologists by county in 2014

eFigure 2. Map of the density of nonphysician clinicians that independently bill Medicare for dermatology-related services by county in 2014

eTable 2. Affiliation of nonphysician clinicians

References

- 1.Guy GP Jr, Machlin SR, Ekwueme DU, Yabroff KR. Prevalence and costs of skin cancer treatment in the US, 2002-2006 and 2007-2011. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(2):183-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resneck JS., Jr Dermatology workforce policy then and now: reflections on Dr Peyton Weary’s 1979 manuscript. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68(2):338-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Resneck JS Jr, Kimball AB. Who else is providing care in dermatology practices? trends in the use of nonphysician clinicians. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(2):211-216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glazer AM, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution of US dermatology workforce density. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(5):472-473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kirch DG, Petelle K. Addressing the physician shortage: the peril of ignoring demography. JAMA. 2017;317(19):1947-1948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, Iacobucci W. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2013 to 2025. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eden J, Berwick D, Wilensky G. Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation’s Health Needs. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gudbranson E, Glickman A, Emanuel EJ. Reassessing the data on whether a physician shortage exists. JAMA. 2017;317(19):1945-1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naylor MD, Kurtzman ET. The role of nurse practitioners in reinventing primary care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):893-899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green LV, Savin S, Lu Y. Primary care physician shortages could be eliminated through use of teams, nonphysicians, and electronic communication. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(1):11-19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraher EP, Morgan P, Johnson A. Specialty distribution of physician assistants and nurse practitioners in North Carolina. JAAPA. 2016;29(4):38-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morgan P, Everett CM, Humeniuk KM, Valentin VL. Physician assistant specialty choice: distribution, salaries, and comparison with physicians. JAAPA. 2016;29(7):46-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Council on Graduate Medical Education Advancing Primary Care: Council on Graduate Medical Education 20th Report. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health & Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration; 2010. http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/gpo11461/twentiethreport.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2017.

- 14.Coldiron B, Ratnarathorn M. Scope of physician procedures independently billed by mid-level providers in the office setting. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(11):1153-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jalian HR, Avram MM. Mid-level practitioners in dermatology: a need for further study and oversight. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(11):1149-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pascoe VL, Kimball AB. Expanding scope of dermatologic mid-level practitioners includes prescription of complex medication. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(1):106-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.American Association of Nurse Practitioners State Practice Environment. https://www.aanp.org/legislation-regulation/state-legislation/state-practice-environment/66-legislation-regulation/state-practice-environment/1380-state-practice-by-type. Accessed July 25, 2017.

- 18.Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Pub L No. 105-33, 111 Stat 251.

- 19.Arnold T. Physician assistants in dermatology. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2008;1(2):28-31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medicare Provider Utilization and Payment Data: Physician and Other Supplier. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/Medicare-Provider-Charge-Data/Physician-and-Other-Supplier.html. Accessed February 6, 2017.

- 21.Adamson AS, Dusetzina SB. Characteristics of Medicare payments to dermatologists in 2013. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(1):95-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties Data File Documentation. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/oae/NCHSUrbruralFileDocumentation.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2017.

- 23.Reines HD, Robinson L, Duggan M, O’Brien BM, Aulenbach K. Integrating midlevel practitioners into a teaching service. Am J Surg. 2006;192(1):119-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawkins CM, Bowen MA, Gilliland CA, Walls DG, Duszak R Jr. The impact of nonphysician providers on diagnostic and interventional radiology practices: operational and educational implications. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12(9):898-904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bahouth M, Esposito-Herr MB, Babineau TJ. The expanding role of the nurse practitioner in an academic medical center and its impact on graduate medical education. J Surg Educ. 2007;64(5):282-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleinpell RM, Ely EW, Grabenkort R. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants in the intensive care unit: an evidence-based review. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(10):2888-2897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Day CS, Boden SD, Knott PT, O’Rourke NC, Yang BW. Musculoskeletal workforce needs: are physician assistants and nurse practitioners the solution? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(11):e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Guidance to Reduce Mohs Surgery Reimbursement Issues. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/SE1318.pdf. Accessed August 7, 2017.

- 29.Resneck JS Jr, VanBeek M. What dermatology still needs to create meaningful patient outcome measurements. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(4):371-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martínez-González NA, Djalali S, Tandjung R, et al. Substitution of physicians by nurses in primary care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mafi JN, Wee CC, Davis RB, Landon BE. Comparing use of low-value health care services among US advanced practice clinicians and physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(4):237-244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nault A, Zhang C, Kim K, Saha S, Bennett DD, Xu YG. Biopsy use in skin cancer diagnosis: comparing dermatology physicians and advanced practice professionals. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151(8):899-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baade PD, Youl PH, Janda M, Whiteman DC, Del Mar CB, Aitken JF. Factors associated with the number of lesions excised for each skin cancer: a study of primary care physicians in Queensland, Australia. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(11):1468-1476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jalian HR, Jalian CA, Avram MM. Increased risk of litigation associated with laser surgery by nonphysician operators. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150(4):407-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glazer AM, Farberg AS, Winkelmann RR, Rigel DS. Analysis of trends in geographic distribution and density of US dermatologists. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153(4):322-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bobonich M, Cooper KD. A core curriculum for dermatology nurse practitioners: using Delphi technique. J Dermatol Nurses Assoc. 2012;4(2):108-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dermatology Nurses’ Association Dermatology Nurse Practitioner FAQs. https://www.dnanurse.org/aboutdna/np-society/np-faq/. Accessed August 8, 2017.

- 38.Glazer AM, Holyoak K, Cheever E, Rigel DS. Analysis of US dermatology physician assistant density. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76(6):1200-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Iglehart JK. Expanding the role of advanced nurse practitioners—risks and rewards. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1935-1941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Number and proportion of services and dermatology-related procedures by clinician type

eFigure 1. Map of the density of US dermatologists by county in 2014

eFigure 2. Map of the density of nonphysician clinicians that independently bill Medicare for dermatology-related services by county in 2014

eTable 2. Affiliation of nonphysician clinicians