Key Points

Question

What are the epidemiologic features and treatment patterns of hearing difficulty in the United States?

Findings

Hearing difficulty is reported by 16.8% of the adult population, and 1 in 5 adults with hearing difficulty had seen a physician for hearing problems, of which one-third were referred to a specialist. Among individuals who could not appreciate shouting in a quiet room, 1 in 20 were recommended to have a cochlear implant (CI), of which one-fifth had received one.

Meaning

Although hearing difficulty remains a prevalent condition nationally, considerable gaps exist in specialist referral patterns and amplification and CI utilization.

This survey study analyzes the epidemiologic features and treatment patterns of hearing difficulty in the United States using data from responses from the 2014 National Health Interview Survey.

Abstract

Importance

Hearing loss is one of the most prevalent chronic conditions in the United States and has been associated with negative physical, social, cognitive, economic, and emotional consequences. Despite the high prevalence of hearing loss, substantial gaps in the utilization of amplification options, including hearing aids and cochlear implants (CI), have been identified.

Objective

To investigate the contemporary prevalence, characteristics, and patterns of specialty referral, evaluation, and treatment of hearing difficulty among adults in the United States.

Design, Setting, and Participants

A cross-sectional analysis of responses from a nationwide clustered representative sample of adults who participated in the 2014 National Health Interview Survey and responded to the hearing module questions was carried out.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Data regarding demographics as well as self-reported hearing status, functional hearing, laterality, onset, and primary cause of the hearing loss were collected. In addition, specific data regarding hearing-related clinician visits, hearing tests, referrals to hearing specialist, and utilization of hearing aids and CIs were analyzed.

Results

Among 239.6 million adults, 40.3 million (16.8%) indicated their hearing was less than “excellent/good,” ranging from “a little trouble hearing” to “deaf.” The mean (SD) age of participants was 47 (0.2) years with 48.2% being men and 51.8% women. Approximately 48.8 million (20.6%) had visited a physician for hearing problems in the preceding 5 years. Of these, 32.6% were referred to an otolaryngologist and 27.3% were referred to an audiologist. Functional hearing was reported as the ability to hear “whispering” or “normal voice” (225.4 million; 95.5%), to “only hear shouting” (8.0 million; 3.4%), and “not appreciating shouting” (2.8 million; 1.1%). Among the last group, 5.3% were recommended to have a CI, of which 22.1% had received one. Of the adults who indicated their hearing from “a little trouble hearing” to being “deaf,” 12.9 million (32.2%) had never seen a clinician for hearing problems and 11.1 million (28.0%) had never had their hearing tested.

Conclusions and Relevance

There are considerable gaps between self-reported hearing loss and patients receiving medical evaluation and recommended treatments for hearing loss. Improved awareness regarding referrals to otolaryngologists and audiologists as well as auditory rehabilitative options among clinicians may improve hearing loss care.

Introduction

Hearing loss is one of the most prevalent chronic conditions in the United States, affecting approximately 16% of the adult population, corresponding to 29 million Americans. The prevalence of hearing loss increases with age and, according to a national study, 77% of adults aged 60 to 69 years had some degree of hearing loss. Importantly, difficulty with hearing has been associated with poorer objective physical functioning in older adults and 31% increased risk for disability, as well as poorer quality of life. The impaired ability to effectively hear and communicate may furthermore result in negative emotional, cognitive, economic, and social consequences and place individuals at safety risk. Notably, several studies have revealed substantial improvement in the quality of life and physical functioning scores in patients with hearing loss following acoustic amplification.

The decision to offer and provide hearing loss patients with hearing aids and cochlear implants depends on various clinical factors, including age, degree and type of hearing loss, anatomical considerations, and self-perceived difficulty with communication. Rehabilitative options range from simple assistive listening devices (ALDs) to hearing aids and cochlear implants (CI). Despite the high prevalence of hearing loss, gaps in the utilization of hearing aids and CIs have been previously identified. The rate of hearing aid usage among adults who meet criteria and could benefit from amplification is estimated to be from 16% to 24.6%. Adult patients with hearing difficulty may present to physicians from different specialties, including otolaryngology, internal medicine, family medicine, or geriatrics. Although these patients are often referred to otolaryngologists and/or audiologists for further evaluation, hearing screening and a discussion of the available therapeutic options could start in their initial encounter with other clinicians. A regional study revealed that 26% of primary care physicians were not aware that CIs can restore hearing in deaf children and adults.

While much has been published regarding hearing loss in patients who present to their physicians, few studies have focused on hearing status and function from the perspective of the potential health care consumer in the general population. In addition, patterns of referrals for further evaluation by a specialist and hearing rehabilitation recommendations from this perspective are also poorly described. In this study, we investigate the contemporary prevalence and characteristics of self-reported hearing difficulty among adults in the United States using the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS). We further analyzed the patterns of medical specialty referral, evaluation, and amplification and CI recommendations for adults with hearing difficulty.

Methods

The NHIS is a program designed and conducted by the National Center for Health Statistics. Since 1957, NHIS has collected data on a broad range of health topics through personal household interviews of a statistically representative sample of the US civilian noninstitutionalized population. Annually, approximately 35 000 to 40 000 households are interviewed nationwide and data regarding approximately 75 000 to 100 000 individuals are collected. Survey instruments, procedures, variable definitions, and quality control processes are documented elsewhere. The data sets contain deidentified data, thus approval for this study by the institutional review board was considered exempt from review. A data use agreement was signed prior to obtaining the data.

The 2014 NHIS data set was queried and adult records were extracted. The records containing data for the hearing module were included. Respondent demographics were analyzed. Hearing-related questions included self-reported hearing status, difficulty in background noise, functional hearing in a quiet room, hearing-related concerns, laterality of hearing difficulty, age when first noticed hearing loss, and primary causes associated with the onset of hearing loss. In addition, data regarding hearing-related physician visits, referral to hearing specialist, hearing testing, hearing aid use, and CIs were analyzed. The survey contained primary and branching questions. Therefore, the “universe” for the branching questions could vary with each “universe” defined as the subset of survey samples who were asked a secondary branching question based on their response to a primary question. This was accounted for and was outlined when reporting the results.

Each record had associated weight and strata data that accounted for the complex clustered design of the survey sample. These variables allowed for extrapolating national estimates and their respective standard errors (SEs). The SPSS statistical software package (version 22.0; SPSS, Inc) was used for all data analyses. P<.05 was considered significant.

Results

Overall, 36 690 records were included in the analysis, which extrapolated to an estimated (SE) 239.6 (2.5) million adults in the United States. The mean (SD) age was 47 (0.2) years. Table 1 presents the demographics and prevalence and characteristics of the self-reported hearing status. Women constituted an estimated (SE) 51.8% (0.4%) of the population. Men were more likely than women to report hearing difficulty (20.1% vs 13.8%, respectively; absolute difference, 6.3%, 95% CI, 5.2%-7.4%). Approximately 199.3 million (83.2%) indicated their hearing status as “excellent” or “good,” whereas 40.3 million (16.8%) had some degree of hearing difficulty from “a little trouble with the hearing” to being “deaf” (“less-than-good”). Hearing in background noise was “never” or “seldom” a problem in 189.0 million (79.0%) while 50.3 million (21.0%) indicated having problems from “about half the time” to “always.” As seen in Table 1, about 147.4 million (62.1%) had never seen a clinician for hearing problems and 117.4 million (49.7%) had never had a hearing test performed. Approximately 48.8 million (20.6%) had seen a physician for a hearing-related problem in the preceding 5 years. Of these, 15.9 million (32.6%) were referred to an otolaryngologist and 13.3 million (27.3%) were referred to an audiologist.

Table 1. Demographics and Self-reported Hearing Characteristics of US Adults.

| Characteristic | No. (SE), millions | % (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 115.5 (1.5) | 48.2 (0.4) |

| Female | 124.1 (1.6) | 51.8 (0.4) |

| Hearing without hearing aid | ||

| Excellent | 120.9 (1.5) | 50.5 (0.4) |

| Good | 78.4 (1.2) | 32.7 (0.4) |

| A little trouble | 25.3 (0.7) | 10.5 (0.3) |

| Moderate trouble | 9.3 (0.4) | 3.9 (0.1) |

| A lot of trouble | 5.1 (0.2) | 2.1 (0.1) |

| Deaf | 0.7 (0.1) | 0.3 (<0.1) |

| Problem with background noise | ||

| Always | 13.0 (0.4) | 5.4 (0.2) |

| Usually | 16.0 (0.6) | 6.7 (0.2) |

| About half the time | 21.3 (0.6) | 8.9 (0.2) |

| Seldom | 51.4 (1.1) | 21.5 (0.4) |

| Never | 137.6 (1.6) | 57.5 (0.5) |

| Last saw clinician about hearing problems | ||

| Never | 147.4 (1.8) | 62.1 (0.4) |

| In the past year | 24.9 (0.6) | 10.5 (0.2) |

| 1-2 Years ago | 14.3 (0.5) | 6.0 (0.2) |

| 3-4 Years ago | 9.6 (0.3) | 4.1 (0.1) |

| 5-9 Years ago | 11.1 (0.4) | 4.7 (0.2) |

| 10-14 Years ago | 9.1 (0.4) | 3.8 (0.2) |

| 15 or More years ago | 21.0 (0.5) | 8.8 (0.2) |

| Last time hearing tested | ||

| Never | 117.4 (1.6) | 49.7 (0.5) |

| In the past year | 19.5 (0.5) | 8.3 (0.2) |

| 1-2 Years ago | 14.2 (0.5) | 6.0 (0.2) |

| 3-4 Years ago | 10.6 (0.4) | 4.5 (0.2) |

| 5-9 Years ago | 18.6 (0.6) | 7.9 (0.2) |

| 10-14 Years ago | 15.1 (0.5) | 6.4 (0.2) |

| 15 or More years ago | 40.8 (0.8) | 17.3 (0.3) |

| Functional hearing in quiet room | ||

| Can hear whisper | 193.8 (2.1) | 82.1 (0.3) |

| Can hear normal voice | 31.6 (0.7) | 13.4 (0.3) |

| Can hear shouting voice | 8.0 (0.3) | 3.4 (0.1) |

| Can hear speaking loudly into good ear | 1.5 (0.1) | 0.6 (0.1) |

| Cannot hear speaking loudly into good ear | 1.3 (0.1) | 0.5 (<0.1) |

Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

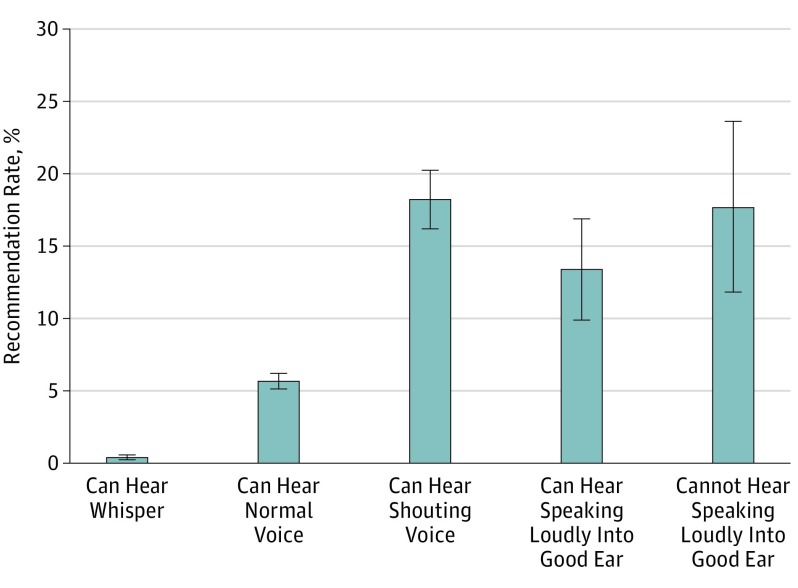

Functional hearing in a quiet room (Table 1) was defined/reported as being able to hear “whispering” or “normal voice” (225.4 million; 95.5%), able to only “hear shouting” (8.0 million; 3.4%), and “not appreciating shouting” (2.8 million; 1.1%). The division of the functional hearing status based on age decades is presented in eTable 1 in the Supplement. Only 0.2 million (5.3%) of the adults who “cannot appreciate shouting” in a quiet room were recommended for a CI, of which 33 921 (22.1%) received one. Hearing aids were overall recommended to 3.7 million (1.6%; SE, 0.1%) individuals. The recommendation rates based on the functional hearing status are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Hearing Aid Recommendation Rates Based on Functional Hearing Status Group.

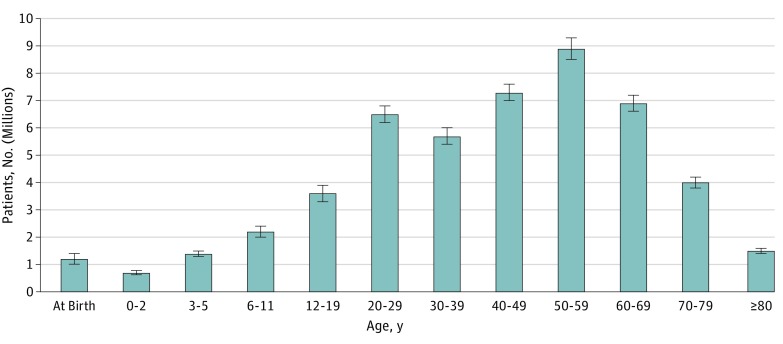

Table 2 presents data regarding the adults with “less-than-good” hearing. Of these adults, 20.5 million (52.8%) indicated poorer hearing in 1 ear (48.4% in right ear and 51.6% in left ear). About 15.7 million (30.5%) stated frustration with their hearing from “about half the time” to “always,” and about 5.5 million (11.2%) indicated their hearing loss generated concerns for their safety. The most common age brackets at first hearing loss were 50 to 59 years (17.7%; SE, 0.7%) followed by 40 to 49 years (14.5%; SE, 0.6%) and 60 to 69 years (13.7%; SE, 0.5%) (Figure 2). Most individuals attributed their hearing difficulty to aging (31.4%) or long-term noise exposure (25.2%) (eTable 2 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Characteristics of Self-reported Hearing Difficulty in Adults Reporting Less-Than-Good Hearing.

| Characteristic | No. (SE), Millions | % (SE) |

|---|---|---|

| Hearing poorer in 1 ear | ||

| Yes | 20.5 (0.5) | 52.8 (0.9) |

| No | 18.3 (0.6) | 47.2 (0.9) |

| Hearing worse in 1 ear, side | ||

| Right | 9.6 (0.3) | 47.5 (1.2) |

| Left | 10.6 (0.4) | 52.5 (1.2) |

| Frustrated with hearing | ||

| Always | 3.4 (0.2) | 8.5 (0.5) |

| Usually | 4.5 (0.2) | 11.1 (0.5) |

| About half the time | 7.8 (0.4) | 19.4 (0.7) |

| Seldom | 12.4 (0.4) | 31.0 (0.8) |

| Never | 12.0 (0.4) | 30.0 (0.8) |

| Hearing causes safety concerns | ||

| Always | 1.2 (0.1) | 3.0 (0.3) |

| Usually | 1.3 (0.1) | 3.3 (0.3) |

| About half the time | 2.0 (0.1) | 4.9 (0.3) |

| Seldom | 7.1 (0.3) | 17.7 (0.7) |

| Never | 28.6 (0.7) | 71.1 (0.8) |

Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

Figure 2. Self-reported Age at Onset of Hearing Loss.

Standard errors are represented as bars.

Table 3 compares the treatment patterns of the adults based on their hearing status. As expected, individuals with “less-than-good” hearing were more likely to be seen by a physician for hearing issues, most of which had a visit within the preceding 5 years. These individuals were also more likely to be referred to a hearing specialist or audiologist and undergo hearing testing. Of the approximately 40.3 million adults with “less-than-good” hearing, 32.2% had never seen a clinician for hearing problems, 48.1% were never referred to a hearing specialist, 45.3% were never referred to an audiologist, and 28.0% had never had their hearing tested.

Table 3. Comparison of Treatment Patterns Between Adults With and Without Hearing Difficulty.

| Treatment | % (SE) | |

|---|---|---|

| Excellent or Good Hearing | A Little Trouble Hearing to Deaf | |

| Last saw physician/clinician about hearing problemsa | ||

| Never | 68.1 (0.4) | 32.2 (1.0) |

| 0-4 Years ago | 15.4 (0.3) | 46.0 (1.0) |

| ≥5 Years ago | 16.5 (0.3) | 21.7 (0.7) |

| Referred to hearing specialista | ||

| Yes | 20.9 (0.9) | 51.9 (1.3) |

| No | 79.1 (0.9) | 48.1 (1.3) |

| Referred to audiologista | ||

| Yes | 10.8 (0.7) | 54.7 (1.2) |

| No | 89.2 (0.7) | 45.3 (1.2) |

| Last time hearing testeda | ||

| Never | 54.1 (0.5) | 28.0 (0.8) |

| 0-4 Years ago | 14.7 (0.3) | 38.5 (0.8) |

| ≥5 Years ago | 31.1 (0.5) | 33.5 (0.9) |

Abbreviation: SE, standard error.

P < .001.

Analysis of the hearing aid portion of the survey revealed that an estimated (SE) 7.3 (0.3) million (3.1%; SE, 0.1%) reported using hearing aids at the time of the survey. The duration of hearing aid use was less than 1 year in an estimated (SE) 0.7 (0.1) million (10.1%; SE, 1.2%), between 1 and 5 years in an estimated (SE) 2.8 (0.2) million (37.9%; SE, 2.0%), and 5 years or more in an estimated (SE) 3.8 (0.2) million (52.0%; SE, 2.0%). The average hearing aid use per day was less than 1 hour in an estimated (SE) 1.0 (0.1) million (13.2%; SE, 1.3%), 1 to 7 hours in an estimated (SE) 1.7 (0.1) million (23.0%; SE, 1.6%), and 8 or more hours in an estimated (SE) 4.6 (0.2) million (63.7%; SE, 2.0%).

Discussion

Hearing difficulty was reported by approximately 40 million adults, equivalent to 16.8% of the national population. Although in this study hearing difficulty was reported subjectively, this rate closely matched the previously reported 16.1% prevalence of hearing loss based on the audiometric data from National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) from 1999 to 2004. A more recent study using the NHANES data from 2011 to 2012 reported that the prevalence of hearing loss had slightly decreased to 14.1%. Nonetheless, hearing difficulty remains one of the most prevalent chronic medical conditions in the United States. Notably, of the 48.8 million (20.6%) who had seen a physician within the preceding 5 years for a hearing complaint, 32.6% were referred to an otolaryngologist and 27.3% were referred to an audiologist, indicating that only a considerable minority of these patients are being referred to advanced hearing care. With expertise in the evaluation of hearing loss and in otologic diseases, otolaryngologists and audiologists play a central role in the care of patients with hearing difficulty. The otolaryngologists can best assess, diagnose, and treat external, middle and inner ear disorders. The audiologists can further characterize patient’s hearing type, perform audiologic evaluations, and help improve the quality of life of hearing-impaired patients by fitting hearing aids, if no medical or surgical treatments are available. With improved patient and referring physician awareness, otolaryngologists can play a more prominent role in the care of these patients and serve to optimize their otologic and rehabilitative outcomes.

Functional hearing was another important aspect of audition investigated in the hearing module of the NHIS. Of note, a considerable number of individuals reported an inability to hear shouting in a quiet room (2.8 million; 1.1%). Remarkably, only 5.3% of these adults received a recommendation for a CI, and only 22.1% of those recommended had received a CI. The lack of familiarity with CIs among physicians may be a contributing factor to this low rate of CI recommendations. In a recent survey of the primary care physicians in 2 southern California counties, almost 1 in 10 physicians were unfamiliar with CI as a treatment option for hearing restoration. Approximately 80% were not aware that CI was covered by all health plans and 26% were not aware that CIs could potentially restore hearing for the deaf and hearing impaired. In addition, inconsistent screening for hearing loss in the primary care setting may result in the underdiagnosis of hearing loss among adults. A household survey found that only 14.6% of the physicians had performed hearing screening (eg, tuning fork or whisper tests) in their offices. As such, many candidates for hearing aids and CIs may go unrecognized. The low rate of CIs in the current study is consistent with the previous estimates of a 5% utilization rate in the eligible adult population with severe to profound hearing loss. A CI was performed in only 1 in 4 individuals who were recommended to receive one. Factors such as patient preference, socioeconomic status, and presence of comorbid conditions may be contributing to this seemingly low rate.

The number of individuals using hearing aids was estimated to be approximately 7.3 million (3.1% of the US population). According to the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), it is estimated that about 28.8 million US adults could benefit from hearing aids, but only 16.0% to 24.6% of the adults aged 20 to 69 years with hearing loss and who are hearing aid candidates have ever used them. The low utilization rates of hearing aids has also been attributed to a number of factors, such as degree of hearing loss, self-recognition of hearing loss, financial limitations, and stigma of wearing hearing devices.

Notably, approximately 50.3 million individuals reported some degree of difficulty with hearing in background noise, which is considerably more than the number of individuals with “less-than-good” hearing (40.2 million). The difference could represent a subset of individuals with excellent or good hearing who may suffer from mild or subclinical degrees of noise-induced injury to the auditory system, which has recently been described as a “hidden hearing loss.” The phenomenon of hidden hearing loss has been suggested to be a consequence of acute or chronic noise trauma, resulting in irreversible damage to the hair cell-neuron junction and eventual degeneration of the auditory nerve. This paradigm has been proposed to be the underlying pathophysiology for difficulty with speech understanding in noisy environments in individuals with normal or near-normal audiograms.

Limitations

The limitations of this study must be considered for proper interpretation of the findings. As with any other survey, the accuracy of the responses was subject to entry and recall bias. The collected data were subjective in nature and no objective data, such as audiometric findings were available. As such, the actual presence of hearing loss based on audiometry could not be determined and no distinction between conductive and sensorineural hearing loss could be made. In addition, the definitions of responses such as “a little trouble hearing” or “moderate trouble” could be subject to some interpretation among the interviewees. Nonetheless, the NHIS provides a unique opportunity to investigate the nationwide prevalence of self-reported hearing difficulty and treatment patterns using a representative sample taken at the household level, rather than at the point-of-care level. One of the important advantages of the NHIS is its focus on the perspective of the patient and health care consumer, which distinguishes it from other national surveys, such as NHANES. Whereas these and other surveys allow for analysis of data obtained at the point of health care delivery, the NHIS enables investigators to assess how patients perceive, manage, and seek care for their hearing difficulty symptoms and to evaluate their resulting health care seeking patterns and behavior.

The findings of the current study can serve to identify the current gaps in the care of patients with hearing difficulty. Increasing awareness of amplification and CI options among physicians and improving access to hearing evaluations and specialists may improve the clinical care of those with hearing loss. Future studies are warranted to further investigate the observed trends of this study.

Conclusions

Hearing difficulty is self-reported by about 16.8% of the adults in the United States. About 20.6% of adults with “less-than-good” hearing had seen a physician for hearing problems in the preceding 5 years. Only a minority of these patients were referred to an otolaryngologist or audiologist. Among individuals who could not appreciate “shouting across a quiet room,” only 5.3% were recommended to have a CI, of which only 22.1% had received one. Of the adults with “less-than-good” hearing, 32.2% had never seen a physician for hearing problems and 28.0% had never had their hearing tested. Increased awareness among clinicians regarding the burden of hearing loss, the importance of early detection and appropriate work-up of hearing loss, and available amplification and CI options can contribute to improved care for individuals with hearing difficulty.

eTable 1. Self-reported functional hearing status based on age decades

eTable 2. Reported etiology of hearing difficulty in adults with “less-than-good” hearing (universe: 18+ year olds with “less-than-good,” hearing not “excellent” or “good”, or those who reported “good” hearing, but hear worse in one ear than the other)

References

- 1.Agrawal Y, Platz EA, Niparko JK. Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2004. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(14):1522-1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen DS, Betz J, Yaffe K, et al. ; Health ABC study . Association of hearing impairment with declines in physical functioning and the risk of disability in older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(5):654-661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, Klein R, Wiley TL, Nondahl DM. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontologist. 2003;43(5):661-668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chisolm TH, Johnson CE, Danhauer JL, et al. A systematic review of health-related quality of life and hearing aids: final report of the American Academy of Audiology Task Force On the Health-Related Quality of Life Benefits of Amplification in Adults. J Am Acad Audiol. 2007;18(2):151-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manrique-Huarte R, Calavia D, Huarte Irujo A, Girón L, Manrique-Rodríguez M. Treatment for hearing loss among the elderly: auditory outcomes and impact on quality of life. Audiol Neurootol. 2016;21(suppl 1):29-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilly O, Hwang E, Smith L, et al. Cochlear implantation in elderly patients: stability of outcome over time. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130(8):706-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valente M. Executive summary: evidence-based best practice guideline for adult patients with severe-to-profound unilateral sensorineural hearing loss. J Am Acad Audiol. 2015;26(7):605-606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Quick Statistics About Hearing. https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing. Accessed January 26, 2017.

- 9.Kochkin S. MarkeTrak VIII: 25-Year Trends in the Hearing Health Market. Hearing Review. 2009. http://hearingloss.org/sites/default/files/docs/Kochkin_MarkeTrak8_OctHR09.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2017.

- 10.Wu EC, Zardouz S, Mahboubi H, et al. Knowledge and education of primary care physicians on management of children with hearing loss and pediatric cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2013;34(4):593-594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NHIS - National Health Interview Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis. Accessed January 26, 2017.

- 12.Hoffman HJ, Dobie RA, Losonczy KG, Themann CL, Flamme GA. Declining prevalence of hearing loss in US adults aged 20 to 69 years. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;143(3):274-285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sorkin DL, Buchman CA. Cochlear implant access in six developed countries. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(2):e161-e164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sorkin DL. Cochlear implantation in the world’s largest medical device market: utilization and awareness of cochlear implants in the United States. Cochlear Implants Int. 2013;14(suppl 1):S4-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carroll YI, Eichwald J, Scinicariello F, et al. Vital signs: noise-induced hearing loss among adults - United States 2011-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(5):139-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Adding insult to injury: cochlear nerve degeneration after “temporary” noise-induced hearing loss. J Neurosci. 2009;29(45):14077-14085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin HW, Furman AC, Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Primary neural degeneration in the guinea pig cochlea after reversible noise-induced threshold shift. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2011;12(5):605-616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kujawa SG, Liberman MC. Synaptopathy in the noise-exposed and aging cochlea: Primary neural degeneration in acquired sensorineural hearing loss. Hear Res. 2015;330(Pt B):191-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liberman MC, Epstein MJ, Cleveland SS, Wang H, Maison SF. Toward a differential diagnosis of hidden hearing loss in humans. PLoS One. 2016;11(9):e0162726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention NHANES - National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes. Accessed January 26, 2017.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Self-reported functional hearing status based on age decades

eTable 2. Reported etiology of hearing difficulty in adults with “less-than-good” hearing (universe: 18+ year olds with “less-than-good,” hearing not “excellent” or “good”, or those who reported “good” hearing, but hear worse in one ear than the other)