Key Points

Questions

Is there an association between smoking status at diagnosis and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) survival? Are married patients with HNSCC more likely to be nonsmokers than smokers?

Findings

In this retrospective cohort study of 463 confirmed cases of HNSCC, patients who were smokers at the time of diagnosis had lower survival than nonsmokers. In addition, smokers were more likely to be unmarried.

Meaning

Smoking at the time of HNSCC diagnosis is associated with lower survival than nonsmoking; married individuals are more likely to be nonsmokers.

Abstract

Importance

While the adverse association between smoking and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) survival has been well described, there are also inconclusive studies and those that report no significant changes in HNSCC survival and overall mortality due to smoking. There is also a lack of studies investigating the association of marital status on smoking status at diagnosis for patients with HNSCC.

Objective

To examine the association between patient smoking status at HNSCC diagnosis and survival and the association between marital status and smoking in these patients.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study was conducted by querying the Saint Louis University Hospital Tumor Registry for adults with a diagnosis of HNSCC and treated at the university academic medical center between 1997 and 2012; 463 confirmed cases were analyzed.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to evaluate association of survival with smoking status at diagnosis and covariates. A multivariate logistic regression model was used to assess whether marital status was associated with smoking at diagnosis adjusting for covariates.

Results

Of the 463 total patients (338 men, 125 women), 92 (19.9%) were aged 18 to 49 years; 233 (50.3%) were aged 50 to 65 years; and 138 (29.8%) were older than 65 years. Overall, 56.2% of patients were smokers at diagnosis (n = 260); 49.6% were married (n = 228); and the mortality rate was 54.9% (254 died). A majority of patients were white (81.0%; n = 375). Smokers at diagnosis were more likely to be younger (ie, <65 years), unmarried, and to drink alcohol. We found a statistically significant difference in median survival time between smokers (89 months; 95% CI, 65-123 months) and nonsmokers at diagnosis (208 months; 95% CI, 129-235 months). In the adjusted Cox proportional hazards model, patients who were smokers at diagnosis were almost twice as likely to die during the study period as nonsmokers (hazard ratio, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.42-2.77). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, unmarried patients were 76% more likely to use tobacco than married patients (adjusted odds ratio, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.08-2.84).

Conclusions and Relevance

Smokers were almost twice as likely as nonsmokers to die during the study period. We also found that those who were married were less likely to be smokers at diagnosis. Our study suggests that individualized cancer care should incorporate social support and management of cancer risk behaviors.

This cohort study examines the association between survival and smoking status at the time of diagnosis of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma and the association between marital status and smoking in these same patients.

Introduction

There are more than 430 000 survivors of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) currently in the United States, and the number is expected to rise. Besides improved treatment modalities and cancer care, major drivers of this survival increase are decreasing smoking rates and increasing human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated oropharyngeal cancer, which typically portend better prognosis. However, even though smoking rate is decreasing nationally, current smokers, recent quitters (within the past 12 months), and former smokers still account for up to 80% of patients with HNSCC in developed countries. Between 72% and 80% of all HNSCC cases are linked to either tobacco alone, alcohol alone, or a synergism of tobacco and alcohol. This makes tobacco’s role in HNSCC as relevant today as ever before.

Tobacco use before and after cancer diagnosis is an established prognostic factor in HNSCC survival and mortality. Besides stage at presentation and tumor site, there is probably no stronger predictor of HNSCC survival than tobacco use. Even among patients with HPV-positive HNSCC, smokers typically fare worse. The same is true for HPV-negative HNSCC. Tobacco use is associated with increased risk of secondary tumors, decreased efficacy of surgical and chemoradiation treatments, and decreased quality of life.

Although the association between smoking and HNSCC outcomes has been well described, these findings have been contradicted by other studies that report no significant or inconclusive changes in local disease, disease-specific survival, and overall mortality in HNSCC. The present study examines whether tobacco use is associated with reduced HNSCC survival. This finding could have important clinical and policy implications, such as including tobacco cessation in the short- and long-term management of patients with HNSCC. While the need to incorporate continuous tobacco screening and cessation programs as part of standard clinical cancer care has been stressed, this is not yet universally available for cancer patients who smoke. Since individuals who smoke often cite stress and social environment as smoking triggers, understanding the adverse effect of smoking on HNSCC survival also warrants investigating the role of social support in mitigating smoking habits. Previous studies have shown that being married may confer survival benefits for patients with HNSCC. However, to our knowledge, no study has investigated the impact of spousal status on smoking status at the time of HNSCC diagnosis. Smoking cessation programs in noncancer patients have achieved success by incorporating couples-oriented interventional strategies, but this has yet to be replicated in the cancer population, let alone HNSCC. Thus, the objectives of this study were 2-fold. First, we aimed to describe the effect of smoking status at diagnosis on survival in HNSCC, and second, we aimed to investigate the association between marital status and smoking status of patients with HNSCC at the time of diagnosis.

Methods

Study Design and Patients

This was a retrospective cohort study based on data obtained from patients who received both outpatient and inpatient care at Saint Louis University Hospital from January 1, 1997, to December 31, 2012. The tumor registry was queried for 463 patients aged 18 to 87 who had a primary diagnosis of HNSCC per International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3) codes. This study was approved by the Saint Louis University institutional review board, waiving patient written informed consent for this retrospective analysis of deidentified data.

Outcome Measures

The outcome for the first aim was mortality (alive vs dead), and for the second aim, it was smoking status at diagnosis (yes vs no). Sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics examined included age (18-49, 50-65, or >65 years), sex, race (white, black, or other), marital status (married or not married), insurance (private, government, or no insurance), and alcohol use (yes or no). Cancer stage at diagnosis was classified using the American Joint Commission on Cancer classification. To compensate for the low number of medical records in certain subgroups, we combined stages I and II as “early stage” and stages III and IV as “late stage.”

Statistical Analysis

We compared sociodemographic characteristics and covariates by smoking status at diagnosis using χ2 tests. For aim 1, we used time-to-event modeling to describe the association between smoking status at diagnosis and risk of death after adjusting for covariates. A patient was censored from the analysis at the end of follow-up, at the time of death, or at their last hospital visit date, whichever came first. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were used to illustrate unadjusted survival times for patients who were smokers and nonsmokers at the time of diagnosis. An adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to evaluate the effects of smoking status at the time of diagnosis and other covariates on survival. We also tested for the interaction effect of smoking at diagnosis and marital status on mortality in the Cox proportional hazards regression model. Hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for mortality risk were calculated to compare smokers and nonsmokers at time of diagnosis. For the second aim, we used a multivariable logistic regression model to assess whether marital status was associated with smoking status at diagnosis. All covariates were included in both the adjusted Cox proportional hazards regression and the adjusted logistic regression models regardless of their association with the outcome variables at the bivariate analysis, since the covariates have all been shown in previous studies to be associated with head and neck cancer outcomes. All tests were 2 sided, and an α ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

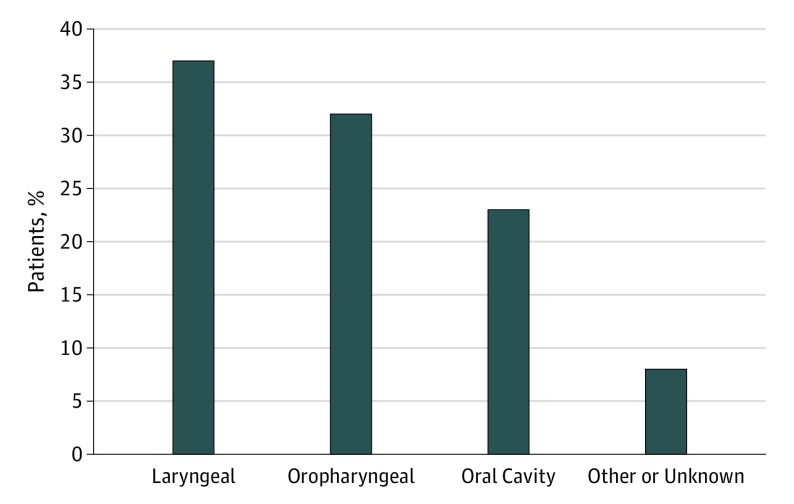

Table 1 details the distribution of sociodemographic characteristics of our study population. The median follow-up time in the study was approximately 81 months (95% CI, 70-89 months). Overall, 56.2% of patients were smokers at diagnosis (n = 260); 49.6% were married (n = 228); and the mortality rate was 54.9% (254 died). A majority of patients were between 50 and 65 years old (50.3%; n = 233), male (73.0%; n = 338), and white (81.0%; n = 375). Smokers at diagnosis were more likely to be younger (ie, <65 years), unmarried, and to drink alcohol. Figure 1 shows the distribution of smokers at diagnosis stratified by anatomical site. The highest number of smokers had cancers of laryngeal cavity (36.5%; n = 95) followed by the oropharyngeal cavity (32.3%; n = 84), and then the oral cavity (23.1%; n = 60).

Table 1. Characteristics of the Study Patients.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Smoker | Nonsmoker | |

| Smoking status | |||

| Smoker | 260 (56.2) | NA | NA |

| Nonsmoker | 203 (43.8) | NA | NA |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 228 (49.6) | 104 (40.3) | 124 (61.4) |

| Not married | 232 (50.4) | 154 (59.7) | 78 (38.6) |

| Mortality | |||

| Alive | 209 (45.1) | 100 (38.5) | 109 (53.7) |

| Dead | 254 (54.9) | 160 (61.5) | 94 (46.3) |

| Age, y | |||

| 18-49 | 92 (19.9) | 60 (23.1) | 32 (15.8) |

| 50-65 | 233 (50.3) | 142 (54.6) | 91 (44.8) |

| >65 | 138 (29.8) | 58 (22.3) | 80 (39.4) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 338 (73.0) | 195 (75.0) | 143 (70.4) |

| Female | 125 (27.0) | 65 (25.0) | 60 (29.6) |

| Race | |||

| White | 375 (81.0) | 203 (78.1) | 172 (84.7) |

| Black | 81 (17.5) | 54 (20.8) | 27 (13.3) |

| Other | 7 (1.5) | 3 (1.1) | 4 (2.0) |

| Insurance | |||

| Private | 213 (46.0) | 105 (40.4) | 108 (53.2) |

| Government | 219 (47.3) | 133 (51.1) | 86 (42.4) |

| No insurance | 31 (6.7) | 22 (8.5) | 9 (4.4) |

| Drinker | |||

| Yes | 245 (52.9) | 467 (64.2) | 78 (38.4) |

| No | 218 (47.1) | 93 (35.8) | 125 (61.6) |

| Cancer stage | |||

| Early | 136 (30.6) | 78 (30.6) | 58 (30.5) |

| Late | 309 (69.4) | 177 (69.4) | 132 (69.5) |

| Treatment type | |||

| Surgery only | 125 (31.2) | 68 (30.5) | 57 (32.0) |

| Surgery with irradiation and/or chemotherapy | 118 (29.4) | 60 (26.9) | 58 (32.6) |

| Irradiation and/or chemotherapy | 158 (39.4) | 92 (42.6) | 63 (35.4) |

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

Figure 1. Distribution of Smokers at the Time of HNSCC Diagnosis by Tumor Subsite.

HNSCC indicates head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Smoking Status at Diagnosis and Survival

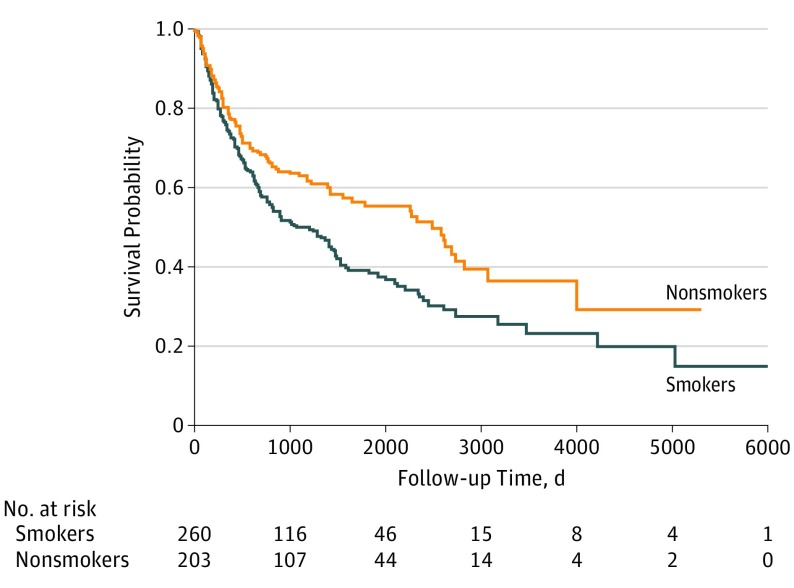

The Kaplan-Meier survival curve (Figure 2) revealed a significant difference in median survival time between smokers and nonsmokers at diagnosis. The median survival time for smokers at diagnosis was 89 months (95% CI, 65-123 months), and for nonsmokers at diagnosis it was 208 months (95% CI, 129-235 months). Table 2 lists the adjusted HRs (aHRs) for death from our Cox proportional hazards regression model. After adjusting for prognostic factors, we found that smokers at diagnosis were twice as likely to die during the study period (aHR, 1.98; 95% CI, 1.42-2.77) compared with nonsmokers at diagnosis. Similarly, unmarried patients had almost twice the hazard of death (aHR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.38-2.53) compared with married patients. Patients aged 65 years or older had more than double the hazard of death (aHR, 2.38; 95% CI, 1.50-3.80) compared with those aged 18 to 49 years. Patients with late-stage disease were more likely to die during the study period (aHR, 1.65; 95% CI, 1.14-2.38) than those with early-stage disease. Finally, patients with oral cavity cancer (aHR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.11-2.75) and patients with cancer of other or unknown anatomical site (aHR, 2.98; 95% CI, 1.77-5.01) were more likely to die during the study period than those with laryngeal cancer. The interaction between smoking status at diagnosis, marital status, and mortality was not significant.

Figure 2. Association of Smoking Status at HNSCC Diagnosis With Survival.

HNSCC indicates head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve shows the unadjusted association between smoking status at diagnosis and survival.

Table 2. Cox Proportional Hazards Model Assessing the Association Between Sociodemographic, Tumor, and Treatment Characteristics and Mortality.

| Characteristic | HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | |

| Smoking status | ||

| Yes | 1.47 (1.40-1.90) | 1.98 (1.42-2.77) |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Marital status | ||

| Not married | 1.78 (1.38-2.29) | 1.87 (1.38-2.53) |

| Married | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Age, y | ||

| >65 | 2.17 (1.49-3.16) | 2.38 (1.50-3.80) |

| 50-65 | 1.58 (1.11-2.26) | 1.37 (0.91-2.07) |

| 18-49 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.08 (0.82-1.44) | 1.18 (0.84-1.64) |

| Female | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Race | ||

| Other | 3.68 (1.63-8.32) | 1.85 (0.65-5.24) |

| Black | 1.52 (1.12-2.07) | 1.23 (0.82-1.84) |

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Insurance | ||

| No insurance | 1.45 (0.87-2.43) | 1.14 (0.59-2.11) |

| Government | 1.77 (1.37-2.30) | 1.05 (0.75-2.19) |

| Private | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Yes | 0.82 (0.64-1.04) | 0.68 (0.50-0.93) |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Stage | ||

| Late | 1.99 (1.48-2.68) | 1.65 (1.14-2.38) |

| Early | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Treatment type | ||

| Irradiation and/or chemotherapy | 1.27 (0.91-1.77) | 1.04 (0.67-1.65) |

| Surgery with irradiation and/or chemotherapy | 1.07 (0.75-1.54) | 0.96 (0.62-1.46) |

| Surgery only | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Anatomical site | ||

| Other or unknown | 2.28 (1.49-3.49) | 2.98 (1.77-5.01) |

| Oropharyngeal | 1.08 (0.80-1.47) | 1.29 (0.88-1.89) |

| Oral cavity | 1.12 (0.80-1.58) | 1.75 (1.11-2.75) |

| Laryngeal | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratio.

Since most patients with oropharyngeal cancer may be HPV positive, which we were unable to assess, a sensitivity analysis was performed excluding those with oropharyngeal cancer, and the results are presented in the eTable in the Supplement. The Kaplan-Meier survival curve (eFigure in the Supplement) from sensitivity analysis revealed a significant difference in median survival time between smokers and nonsmokers at diagnosis. The median survival time was the same as in the original analysis; 208 months for smokers and 89 months for nonsmokers at diagnosis. The multivariable Cox proportional model from the sensitivity analysis showed that smokers at diagnosis had twice the hazard of death (aHR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.50-3.59) compared with nonsmokers at diagnosis. Smoking status hazards of death changed slightly from 1.98 in the original analysis to 2.32 in the sensitivity analysis. Similarly, patients who were unmarried had twice the hazard of death (aHR, 2.04; 95% CI, 1.39-2.99) compared with those who were married. Marital status hazards of death changed slightly from 1.87 in the original analysis to 2.04 in the sensitivity analysis.

Marital Status and Smoking at Diagnosis

Table 3 lists the adjusted multivariate odds ratios (aORs) for the association of marital status and other covariates with smoking status at diagnosis. After adjusting for prognostic factors, we found that marital status, age, insurance, alcohol use, and anatomical site were significantly associated with smoking status at diagnosis. Compared with married patients, unmarried patients were almost twice as likely to be smokers at diagnosis (aOR, 1.77; 95% CI, 1.09-2.87). Patients aged 65 years or older were 78% less likely to be smokers at diagnosis (aOR = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.11-0.46) than those aged 18 to 49 years. Patients who reported alcohol use were almost 3 times as likely (aOR, 2.96; 95% CI, 1.85-4.72), while those who reported using government insurance were approximately twice as likely (aOR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.24-3.67), to be smokers at diagnosis. Finally, patients with cancer of the oral cavity (aOR, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.17-0.70), oropharyngeal cavity (aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.16-0.56), and cancer of other or unknown sites (aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.12-0.78) were less likely to be smokers at diagnosis than those with laryngeal cancer.

Table 3. Logistic Regression Model Assessing the Association Between Sociodemographic, Tumor, and Treatment Characteristics and Smoking Status at Diagnosis.

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted | |

| Marital status | ||

| Not married | 2.10 (1.39-3.16) | 1.77 (1.09-2.87) |

| Married | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Age, y | ||

| >65 | 0.40 (0.22-0.72) | 0.22 (0.11-0.46) |

| 50-65 | 0.81 (0.49-1.40) | 0.68 (0.37-1.25) |

| 18-49 | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.25 (0.80-1.95) | 1.12 (0.66-1.88) |

| Female | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Race | ||

| Other | 2.47 (0.25-23.9) | 3.25 (0.27-39.8) |

| Black | 1.57 (0.89-2.78) | 1.19 (0.61-2.32) |

| White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Insurance | ||

| No insurance | 3.34 (1.18-9.50) | 1.80 (0.58-5.53) |

| Government | 1.74 (1.14-2.63) | 2.14 (1.24-3.67) |

| Private | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Alcohol use | ||

| Yes | 2.81 (1.85-4.26) | 2.96 (1.85-4.72) |

| No | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Stage | ||

| Late | 0.94 (0.62-1.45) | 1.10 (0.62-1.93) |

| Early | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Treatment type | ||

| Irradiation and/or chemotherapy | 1.26 (0.77-2.05) | 0.86 (0.42-1.76) |

| Surgery with irradiation and/or chemotherapy | 0.79 (0.47-1.32) | 0.59 (0.30-1.15) |

| Surgery only | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

| Anatomical site | ||

| Other or unknown | 0.43 (0.19-0.97) | 0.30 (0.12-0.78) |

| Oropharyngeal | 0.44 (0.26-0.74) | 0.30 (0.16-0.56) |

| Oral cavity | 0.46 (0.26-0.79) | 0.34 (0.17-0.70) |

| Laryngeal | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

Discussion

Our study aimed to examine the association between tobacco smoking and marital status in patients with HNSCC and to evaluate the association of smoking status with survival. We established that the smoking rate was very high among this patient population: unmarried patients were more likely to be smokers at the time of diagnosis, and smokers were more likely to die during the study period than nonsmokers. The latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report estimates that 15.1% of US adults are current smokers, and that smoking rates continue to drop across the United States. However, it is evident that this decreasing smoking rate is not uniform across all groups. Among cancer patients, smoking rates are much higher: nearly 62% of recently diagnosed cancer patients across the United States identified as current smokers, recent quitters, or former smokers, with the highest numbers in lung cancer and HNSCC. In the present study, approximately 56% of patients were current smokers at diagnosis, which is more than 3 times the current national smoking rate. Previous HNSCC studies have reported varying rates of smoking at diagnosis, ranging from 26.4% to 56%. Smoking rates tend to be heterogeneous across head and neck subsites, with the larynx having the higher rates and a greater likelihood of being associated with smoking. Our study confirms this. We found that patients with laryngeal cancer had a significantly higher smoking rate than patients with cancer of the other subsites. It is important note these differences when tracking smoking status of patients with HNSCC across the cancer continuum.

Not only is tobacco use a risk factor for HNSCC development, but smoking at diagnosis is associated with decreased survival, increased risk for second primary cancers of the lung, esophagus, and even prostate, hypoxic radioresistance during radiation treatment, as well as increased risk of comorbidities and competing causes of death such as cardiovascular and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Despite the recent focus on HPV-positive HNSCC, smoking remains as important as oral HPV as a risk factor for patients with HNSCC. Most patients in our study developed primary cancer in subsites that are mostly unrelated to HPV, as described by Chaturvedi and colleagues. There is evidence that smoking significantly increases the odds of developing persistent oral HPV and HPV-associated HNSCC independent of sexual behaviors. Therefore, there is need for tobacco prevention and control to remain an important aspect of head and neck cancer intervention strategies regardless of HPV status.

We found that patients with HNSCC who were smokers at diagnosis were almost twice as likely to die during the study period as nonsmokers, which is consistent with previous studies. There are several proposed mechanisms for smoking-induced effects on survival in HNSCC. Some suggest that tobacco use increases inflammatory reactions, induces nicotine dose-dependent DNA damage, and increases production of matrix metalloprotein-2 and -9. Whatever the mechanism of action, our study adds more evidence that tobacco use at the time of diagnosis is associated with poorer overall survival of patients with HNSCC.

Our findings on the negative association of smoking with mortality before HNSCC treatment have clinically significant implications. Studies have shown that smokers’ knowledge of a causal relationship between smoking and their cancer is a successful motivator for tobacco cessation. Our findings add evidence to calls for more standardized tobacco-related assessments, increased smoking cessation efforts, and lifelong surveillance of cancer patients. Although smoking cessation is offered to patients at the time of diagnosis, many physicians do not consistently offer it as part of standard of care for those with HNSCC. In fact, a recent survey suggests that fewer than half of oncologists actually offer assistance with smoking cessation. The American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) both recommend integrating smoking cessation into the care of cancer patients. Since 14% to 59% of patients with HNSCC continue to smoke after their cancer diagnosis, continuous monitoring of smoking status and tobacco cessation efforts may play a critical role in the care of HNSCC patients with any history of smoking.

We found that HNSCC patients who were married were less likely to be smokers at diagnosis. Although previous studies have noted the association between marital status and survival in HNSCC, ours is the first study to our knowledge to report this association between marital status and smoking at diagnosis after adjusting for other covariates. Previous studies have described the association between marital status and smoking among other populations, such as pregnant women and successful quitters. Although the present study did not distinguish between recent quitters, quitters, and never smokers, our findings nevertheless highlight the importance of spousal status in tobacco abstinence. We suggest that personalized cancer care, especially for HNSCC patients, should incorporate social support particularly in managing cancer-associated behaviors such as smoking. Kashigar et al identified the critical role of an individual’s social environment, such as family and peer support, on smoking cessation in HNSCC patients. Involving spouses and other key social support systems may be worthwhile in tobacco smoking reduction effort among HNSCC patients, described as a vulnerable population often with limited social support living in socially deprived environments. Patients with HNSCC who fit this profile may need extra support to quit smoking, and marital support may be effective in this regard.

Limitations

Our study had limitations. First, its retrospective design restricted which covariates we could analyze. Follow-up data on survivorship in our cohort of patients with HNSCC would have provided a more complete and accurate interpretation of the association of smoking and marital status on survival. In the current study, we could not access how changes in marital status affected smoking status after cancer diagnosis. Moreover, we were not able to stratify nonsmokers at diagnosis into recent quitters, long-term quitters, and never smokers. This would have provided a clearer picture of the effect of any tobacco use on HNSCC survivorship. Previous studies have suggested that recent quitters and exsmokers have improved clinical outcomes compared with current smokers. We recommend that future studies describe both smoking history and intensity. Additionally, future prospective studies should investigate whether changes in marital status affect smoking status. For example, are nonsmokers at diagnosis more likely to smoke after a divorce? Or are former smokers at diagnosis more likely to start smoking again owing to widowhood or divorce? We hypothesize that changes in marital status after diagnosis will affect smoking status and overall outcomes. Furthermore, we did not have information on HPV status that could have affected our findings, since HPV-positive patients tend to have better prognosis. Finally, the status of tobacco use in our study was determined by self-report, without confirmation by biochemical assessments such as carbon monoxide breathalyzers and urine or salivary cotinine tests.

Conclusions

Despite its limitations, the present study demonstrates the interplay between marital status and smoking at diagnosis for patients with HNSCC, and it has added to the existing evidence of an association between tobacco smoking and HNSCC survival. The main strength of the study is the significant finding of the association between smoking status at diagnosis and marital status, an important component of a patient’s social environment and support. This has not been previously reported and represents an important avenue for consideration in smoking prevention and smoking cessation programs in patients with HNSCC cancer. Although overall smoking rates continue to decline, smoking remains a significant causative factor in up to 80% of patients diagnosed with HNSCC. This warrants increased intervention in this cancer population. Future research should examine the effect of tobacco cessation and timing of cessation on survival. Moreover, given the significant association between patients’ marital status and improved survival, it would be interesting to monitor marital status of cancer patients over the course of their disease and correlate changes with smoking status and survival. In addition, future research should examine other social factors such as the number of friends who smoke, socioeconomic status, and level of education to better identify and target high-risk cancer patients for intervention.

In summary, smoking status at diagnosis was associated with survival of patients with head and neck cancer: patients who were smokers at diagnosis were more likely to die during the study period than those who were not smokers at diagnosis. Married patients were less likely to be smokers at diagnosis. These findings highlight the need for clinicians to discuss and encourage spousal involvement in tobacco cessation efforts to mitigate risky behaviors that negatively affect head and neck cancer survival. Individualized cancer care should incorporate social support and management of cancer risk behaviors. However, since we have shown that marital status may confer survival advantage, there is the unanswered question of how to provide meaningful support for patients with HNSCC who are unmarried. Future studies are needed to identify and evaluate the effectiveness of other feasible, nonmarital support systems for nonmarried patients with HNSCC. Finally, it is important to understand the underlying mechanism in the association between smoking status and marital status at the diagnosis of HNSCC.

eTable. Cox proportional hazards model assessing the association between sociodemographic, tumor, and treatment characteristics and mortality

eFigure. Kaplan-Meier survival curve showing the unadjusted association between smoking status at diagnosis and mortality

References

- 1.Cohen EE, LaMonte SJ, Erb NL, et al. American Cancer Society head and neck cancer survivorship care guideline. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(3):203-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osazuwa-Peters N, Adjei Boakye E, Walker RJ, Varvares MA. Suicide: a major threat to head and neck cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(10):1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ringash J. Survivorship and quality of life in head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29):3322-3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kawakita D, Hosono S, Ito H, et al. Impact of smoking status on clinical outcome in oral cavity cancer patients. Oral Oncol. 2012;48(2):186-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anantharaman D, Muller DC, Lagiou P, et al. Combined effects of smoking and HPV16 in oropharyngeal cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(3):752-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Chuang SC, et al. Interaction between tobacco and alcohol use and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(2):541-550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warnakulasuriya S. Global epidemiology of oral and oropharyngeal cancer. Oral Oncol. 2009;45(4-5):309-316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy SA, Ronis DL, McLean S, et al. Pretreatment health behaviors predict survival among patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(12):1969-1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharp L, McDevitt J, Carsin AE, Brown C, Comber H. Smoking at diagnosis is an independent prognostic factor for cancer-specific survival in head and neck cancer: findings from a large, population-based study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(11):2579-2590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Browman GP, Wong G, Hodson I, et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on the efficacy of radiation therapy in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(3):159-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warren GW, Kasza KA, Reid ME, Cummings KM, Marshall JR. Smoking at diagnosis and survival in cancer patients. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(2):401-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mayne ST, Cartmel B, Kirsh V, Goodwin WJ Jr. Alcohol and tobacco use prediagnosis and postdiagnosis, and survival in a cohort of patients with early stage cancers of the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(12):3368-3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karam-Hage M, Cinciripini PM, Gritz ER. Tobacco use and cessation for cancer survivors: an overview for clinicians. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(4):272-290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillison ML, Zhang Q, Jordan R, et al. Tobacco smoking and increased risk of death and progression for patients with p16-positive and p16-negative oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(17):2102-2111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaturvedi AK, D’Souza G, Gillison ML, Katki HA. Burden of HPV-positive oropharynx cancers among ever and never smokers in the U.S. population. Oral Oncol. 2016;60:61-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ljøkjel B, Haave H, Lybak S, et al. The impact of HPV infection, smoking history, age and operability of the patient on disease-specific survival in a geographically defined cohort of patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Acta Otolaryngol. 2014;134(9):964-973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jégu J, Binder-Foucard F, Borel C, Velten M. Trends over three decades of the risk of second primary cancer among patients with head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2013;49(1):9-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jensen K, Jensen AB, Grau C. Smoking has a negative impact upon health related quality of life after treatment for head and neck cancer. Oral Oncol. 2007;43(2):187-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.López RV, Zago MA, Eluf-Neto J, et al. Education, tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, and IL-2 and IL-6 gene polymorphisms in the survival of head and neck cancer. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2011;44(10):1006-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hong AM, Martin A, Chatfield M, et al. Human papillomavirus, smoking status and outcomes in tonsillar squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2013;132(12):2748-2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lassig AA, Yueh B, Joseph AM. The effect of smoking on perioperative complications in head and neck oncologic surgery. Laryngoscope. 2012;122(8):1800-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verschuur HP, Irish JC, O’Sullivan B, Goh C, Gullane PJ, Pintilie M. A matched control study of treatment outcome in young patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Laryngoscope. 1999;109(2 Pt 1):249-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Graeff A, de Leeuw JR, Ros WJ, Hordijk GJ, Blijham GH, Winnubst JA. Sociodemographic factors and quality of life as prognostic indicators in head and neck cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37(3):332-339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gritz ER, Toll BA, Warren GW. Tobacco use in the oncology setting: advancing clinical practice and research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(1):3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gritz ER, Dresler C, Sarna L. Smoking, the missing drug interaction in clinical trials: ignoring the obvious. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(10):2287-2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Warren GW, Marshall JR, Cummings KM, et al. Addressing tobacco use in patients with cancer: a survey of American Society of Clinical Oncology members. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(5):258-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moylan S, Jacka FN, Pasco JA, Berk M. How cigarette smoking may increase the risk of anxiety symptoms and anxiety disorders: a critical review of biological pathways. Brain Behav. 2013;3(3):302-326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.US Department of Health and Human Services Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: a report of the Surgeon General, 2012. https://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/preventing-youth-tobacco-use/index.html. Accessed September 6, 2017.

- 29.Osazuwa-Peters N, Massa ST, Christopher KM, Walker RJ, Varvares MA. Race and sex disparities in long-term survival of oral and oropharyngeal cancer in the United States. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2016;142(2):521-528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osazuwa-Peters N, Christopher K, Massa S, et al. Does being married independently predict survival in patients with head and neck cancer? results from a single institution. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016;94(4):961. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.12.322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Skoyen JA, Jensen M, Mehl MR. We-talk, communal coping, and cessation success in a couple-focused intervention for health-compromised smokers. Fam Process. 2012;51(1):107-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson TL, Pagedar NA, Karnell LH, Funk GF. Factors associated with mortality in 2-year survivors of head and neck cancer. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(11):1100-1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osazuwa-Peters N, Christopher KM, Hussaini AS, Behera A, Walker RJ, Varvares MA. Predictors of stage at presentation and outcomes of head and neck cancers in a university hospital setting. Head Neck. 2016;38(suppl 1):E1826-E1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hashibe M, Brennan P, Benhamou S, et al. Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(10):777-789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Current cigarette smoking among adults in the United States. 2016; https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/adult_data/cig_smoking/.

- 36.Zhang Y, Wang R, Miao L, Zhu L, Jiang H, Yuan H. Different levels in alcohol and tobacco consumption in head and neck cancer patients from 1957 to 2013. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yukiomi K, Yoshiyuki K, Syuhei T, et al. Association between head-and-neck cancers and active and passive cigarette smoking. Health. 2012;4(9):619-624. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baxi SS, Pinheiro LC, Patil SM, Pfister DG, Oeffinger KC, Elkin EB. Causes of death in long-term survivors of head and neck cancer. Cancer. 2014;120(10):1507-1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rose BS, Jeong JH, Nath SK, Lu SM, Mell LK. Population-based study of competing mortality in head and neck cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(26):3503-3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simeoni R, Breitenstein K, Eßer D, Guntinas-Lichius O. Cardiac comorbidity in head and neck cancer patients and its influence on cancer treatment selection and mortality: a prospective cohort study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273(9):2765-2772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yamamoto VN, Thylur DS, Bauschard M, Schmale I, Sinha UK. Overcoming radioresistance in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2016;63:44-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Anderson WF, Gillison ML. Incidence trends for human papillomavirus-related and -unrelated oral squamous cell carcinomas in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(4):612-619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kero K, Rautava J, Syrjänen K, Willberg J, Grenman S, Syrjänen S. Smoking increases oral HPV persistence among men: 7-year follow-up study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33(1):123-133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beachler DC, Sugar EA, Margolick JB, et al. Risk factors for acquisition and clearance of oral human papillomavirus infection among HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2015;181(1):40-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smith EM, Rubenstein LM, Haugen TH, Hamsikova E, Turek LP. Tobacco and alcohol use increases the risk of both HPV-associated and HPV-independent head and neck cancers. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21(9):1369-1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yanbaeva DG, Dentener MA, Creutzberg EC, Wesseling G, Wouters EF. Systemic effects of smoking. Chest. 2007;131(5):1557-1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleinsasser NH, Sassen AW, Semmler MP, Harréus UA, Licht A-K, Richter E. The tobacco alkaloid nicotine demonstrates genotoxicity in human tonsillar tissue and lymphocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2005;86(2):309-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Allam E, Zhang W, Al-Shibani N, et al. Effects of cigarette smoke condensate on oral squamous cell carcinoma cells. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56(10):1154-1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ostroff JS, Dhingra LK. Smoking cessation and cancer survivors In: Feuerstein M, ed. Handbook of Cancer Survivorship. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG; 2007:303-322. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharp L, Johansson H, Fagerström K, Rutqvist LE. Smoking cessation among patients with head and neck cancer: cancer as a ‘teachable moment’. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2008;17(2):114-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi SH, Terrell JE, Bradford CR, et al. Does quitting smoking make a difference among newly diagnosed head and neck cancer patients? Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(12):2216-2224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Land SR, Warren GW, Crafts JL, et al. Cognitive testing of tobacco use items for administration to patients with cancer and cancer survivors in clinical research. Cancer. 2016;122(11):1728-1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Land SR, Toll BA, Moinpour CM, et al. Research priorities, measures, and recommendations for assessment of tobacco use in clinical cancer research. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(8):1907-1913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toll BA, Brandon TH, Gritz ER, Warren GW, Herbst RS; AACR Subcommittee on Tobacco and Cancer . Assessing tobacco use by cancer patients and facilitating cessation: an American Association for Cancer Research policy statement. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(8):1941-1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hanna N, Mulshine J, Wollins DS, Tyne C, Dresler C. Tobacco cessation and control a decade later: American Society of Clinical Oncology policy statement update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(25):3147-3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cox LS, Africano NL, Tercyak KP, Taylor KL. Nicotine dependence treatment for patients with cancer. Cancer. 2003;98(3):632-644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCarter K, Martínez Ú, Britton B, et al. Smoking cessation care among patients with head and neck cancer: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2016;6(9):e012296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Aizer AA, Chen MH, McCarthy EP, et al. Marital status and survival in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(31):3869-3876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Inverso G, Mahal BA, Aizer AA, Donoff RB, Chau NG, Haddad RI. Marital status and head and neck cancer outcomes. Cancer. 2015;121(8):1273-1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schneider S, Schütz J. Who smokes during pregnancy? a systematic literature review of population-based surveys conducted in developed countries between 1997 and 2006. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13(2):138-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lee CW, Kahende J. Factors associated with successful smoking cessation in the United States, 2000. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1503-1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kashigar A, Habbous S, Eng L, et al. Social environment, secondary smoking exposure, and smoking cessation among head and neck cancer patients. Cancer. 2013;119(15):2701-2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Cox proportional hazards model assessing the association between sociodemographic, tumor, and treatment characteristics and mortality

eFigure. Kaplan-Meier survival curve showing the unadjusted association between smoking status at diagnosis and mortality