Abstract

Glutathione transferase classical GSH conjugation activity plays a critical role in cellular detoxification against xenobiotics and noxious compounds as well as against oxidative stress. However, this feature is also exploited by cancer cells to acquire drug resistance and improve their survival. As a result, various members of the family were found overexpressed in a number of different cancers. Moreover several GST polymorphisms, ranging from null phenotypes to point mutations, were detected in members of the family and found to correlate with the onset of neuro-degenerative diseases. In the last decades, a great deal of research aimed at clarifying the role played by GSTs in drug resistance, at developing inhibitors to counteract this activity but also at exploiting GSTs for prodrugs specific activation in cancer cells. Here we summarize some of the most important achievements reached in this lively area of research.

Introduction

The superfamily of glutathione transferases (GSTs) is composed of multifunctional proteins widely distributed in nature, in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes1–5. In eukaryotes, GSTs are divided according to their cellular localization into at least three major families of proteins, namely cytosolic GSTs, mitochondrial GSTs and microsomal GSTs1,2,6. Cytosolic GSTs are spreadily distributed and in turn divided into several major classes on the basis of their chemical, physical and structural properties. Mitochondrial GSTs are also known as kappa class GSTs and are soluble enzymes which bear structural similarities with cytosolic GSTs. On the contrary, microsomal GSTs, also known as MAPEG (membrane-associated proteins involved in eicosanoid and glutathione metabolism), are integral membrane proteins which are not evolutionary related to the other major classes.

This review focuses on the main substrates, inhibitors and reactions played by cytosolic GSTs, with an eye on their relevance for human disease; as to mitochondrial GSTs and MAPEG, we refer the reader to other excellent reviews7,8.

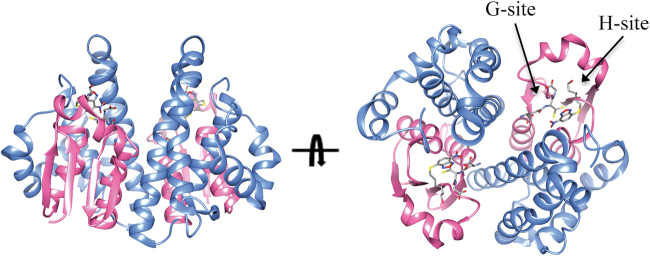

Cytosolic GSTs are classified on the basis of sequence similarities and structural properties. Many classes have been recognized so far, some of them with multiple members which may share sequence identities around 40%. Interclass sequence identities are instead around 25% or less6. Despite the low sequence identities, all cytosolic GSTs share a common fold, which is also largely conserved in mitochondrial GSTs (Fig. 1). In humans, members of the following classes of cytosolic GSTs are present: alpha, zeta, theta, mu, pi, sigma and omega6. GSTs are dimeric enzymes. Usually dimers are made from identical chains but heterodimers made of two different chains from the same class are also found. Two distinct domains are recognized in each GST monomer: a N-terminal thioredoxin-like domain and a C-terminal alpha-helical domain. The first domain is responsible for GSH binding, with the presence of a specific binding task which is termed G-site. Within this site, a specific residue activates the GSH cysteinyl side chain through hydrogen-bonding. In some classes this residue is a tyrosine while in some other is a serine or a cysteine. In humans, alpha, mu, pi and sigma isoenzymes contain a tyrosine in the G-site while the other classes a serine or a cysteine. Mitochondrial kappa class enzymes, contain a serine in the G-site and resemble theta class enzymes. However they also show differences in the overall fold with the presence of a DsbA-like domain inserted within the N-terminal thioredoxin-like domain6. The C-terminal domain contributes, together with the N-terminal domain, to shaping the co-substrate binding site, which is termed H-site, from the hydrophobic nature of co-substrates. The great variability of GSTs co-substrates is reflected in the different H-sites shapes and chemical characters found among classes.

Fig. 1. Structure of a representative GST.

The structure of human GSTP1-1 in complex with GSH and the inhibitor NBDHEX is shown (pdb code 3GUS). The N-terminal thioredoxin-like domain is coloured in pink while the all-helical C-terminal domain is coloured in cyan. The G-site is occupied by a GSH molecule while the H-site is occupied by a NBDHEX molecule which are shown in sticks

GST conjugation activity

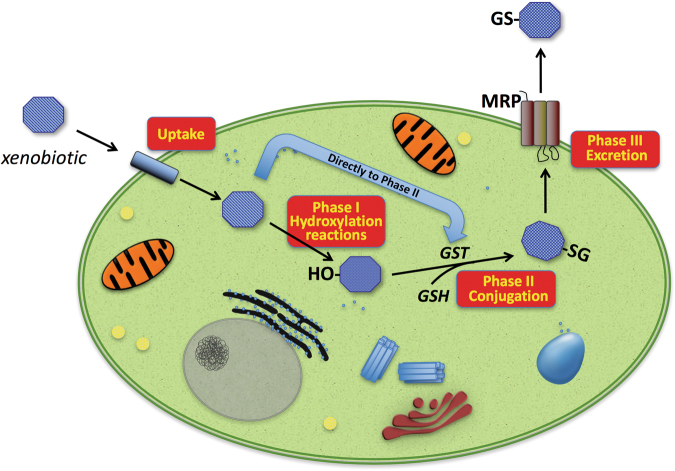

GSTs have multiple biological roles, including cell protection against oxidative stress and several toxic molecules, and are involved in the synthesis and modification of leukotrienes and prostaglandins1. As an example, GSTs protect cellular DNA against oxidative damage that can lead to an increase of DNA mutations or induce DNA damage promoting carcinogenesis9. GSTs are able to conjugate glutathione (γ-l-glutamyl-l-cysteinyl-glycine, GSH) to a wide range of hydrophobic and electrophilic molecules including many carcinogens, therapeutic drugs, and many products of oxidative metabolism, making them less toxic and predisposed to further modification for discharge from the cell (Fig. 2)1.

Fig. 2. Overview of enzymatic biotransformation of xenobiotics.

Harmful molecules may diffuse across the plasma-membrane and, inside cells, they may be targeted by the enzymes of the so-called Phase I metabolism. Main ones belong to the cytochrome P450 family, comprising several enzymes catalyzing different reactions including hydroxylation—the major reaction involved—oxidation and reduction. In the subsequent Phase II metabolism, the main role is played by GSTs that catalyze the conjugation of Phase I-modified xenobiotics to endogenous GSH. The conjugate obtained is then actively transported out of the cell by different transmembrane efflux pumps (Phase III). Some compounds may enter Phase II metabolism directly

A few examples of the detoxification role played by GSTs through their conjugation activity are as follows:

Aflatoxin B1

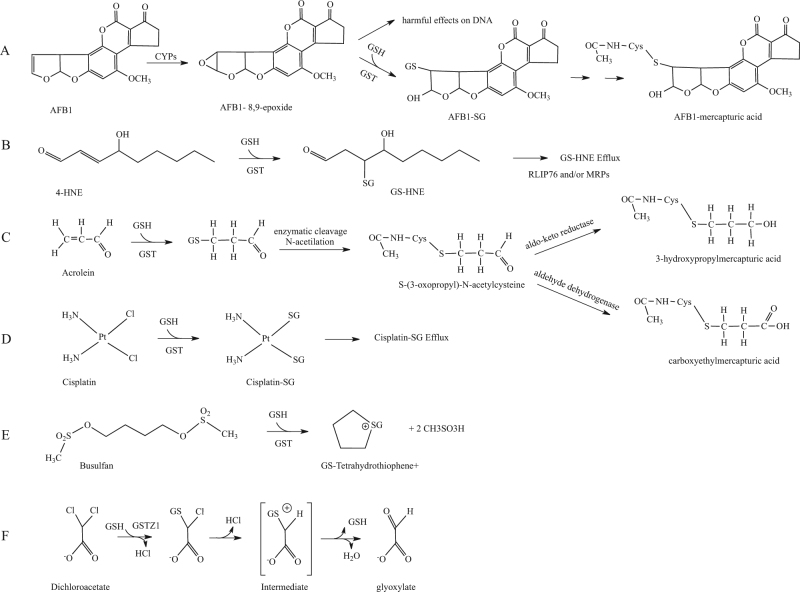

Aflatoxins are harmful metabolites produced by several Aspergillus species. They are highly toxic to the liver and are amongst the major identified risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma10–12. Aflatoxin B1 (AFB1) is present in the environment as contaminant of cereal crops and groundnuts. The toxic effects of AFB1 arise through its enzymatic activation by cytochromes P450 to form highly reactive AFB1-8,9-epoxides. AFB1-exo-8,9-epoxide is then able to bind to guanine residues in DNA thus confering mutagenic properties. GSTs are involved in the main detoxification route of AFB1-exo-8,9-epoxide by catalyzing the conjugation of AFB1-exo-8,9-epoxide to endogenous GSH. The conjugation adduct obtained is then eliminated by the mercapturic acid pathway (Fig. 3a). Drugs-induced increased expression of GSH could play an important role in the protection against the toxic effects of AFB112.

Fig. 3. GST substrates.

a First two steps of the metabolism of aflatoxin B1; b detoxification pathway of 4-hydroxynonenal involving GST; c GST-catalyzed conjugation of acrolein and subsequent trasnformation steps d enzymatic inactivation of cisplatin catalyzed by GSTs; e first step of the metabolic pathway of busulfan; f enzymatic inactivation of dichoroacetate leadind to glyoxylate

4-Hydroxynonenal

4-Hydroxynonenal (4HNE) is a lipoperoxidation-derived aldehyde that can damage proteins and DNA through the generation of covalent adducts and is implicated in the control of cell signaling13,14. Intracellular concentrations of 4HNE may be critical for cells13. High concentrations of 4HNE have been associated with different processes such as apoptosis, cell differentiation, altered gene expression and with several diseases correlated to redox imbalance such as neurodegenerative and cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome, and cancer15. Several enzymatic pathways are involved in protecting cells against 4HNE injury. The major detoxification pathway of 4HNE involves GSTs16. GSTs conjugate 4HNE to GSH, and the corresponding glutathionyl-4-HNE (GS-HNE) is actively transported out of cells via RLIP76, a multifunctional membrane transporter for GSH-conjugated compounds, and/or MRPs (multidrug-resistance proteins; Fig. 3b)15,17.

Acrolein

Acrolein is a highly reactive aldehyde used in the synthesis of several organic compounds in chemical industry and as a biocide in agriculture. Acrolein can be formed by burning tobacco, wood, plastic and fuels, and in the heating of animals and vegetables fats and oils at high temperatures. It is also formed naturally in small amounts in the body as an end-product of lipid oxidation and the metabolism of α-hydroxyamino acids18. Populations exposed to high concentrations of this toxic compound include smokers and second-hand tobacco smokers. Acrolein exerts its toxic effects through inhalation, ingestion and dermal exposure. Cardiovascular tissues are particularly sensitive to the compound19. Acrolein can react and form adducts with DNA, lipids and proteins leading to cellular damage in several human tissues. GST is involved in the first step of the main pathway for elimination of acrolein from the body20. GSTs catalyze the conjugation of acrolein to GSH and the corresponding conjugate is further modified by the enzymatic cleavage of the GSH glutamic acid and glycine residues by γ-glutamyltranspeptidase and cysteinylglycinase, respectively. The cysteine conjugate product is then N-acetylated by N-acetyl-transferase20. At this point further modifications catalyzed by aldehyde dehydrogenase and aldo-keto reductase allow to obtain carboxyethylmercapturic acid and 3-hydroxypropylmercapturic acid respectively, which are escreted with urine (Fig. 3c).

GST's other enzymatic activities

In addition to the classical conjugation reactions, GSTs have a role in several other catalytic functions. GSTs exhibit glutathione peroxidase activity and catalyze the reduction of organic hydroperoxides to their corresponding alcohols. Among the compounds that the enzyme reduces there are phospholipids, fatty acids and DNA hydroperoxides produced by lipid peroxidation and oxidative damage to DNA1. GSTs also show thiol transferase activity and have a role in thiolysis and isomerization reactions1. Three different mechanisms of GST-catalyzed isomerization are known: (i) carbon-carbon double bond shifts, (ii) intramolecular redox reactions and (iii) cis-trans isomerizations21. As an example, GSTZ1-1 catalyzes the cis-trans isomerization of 4-maleylacetoacetate to 4-fumarylacetoacetate within the phenylalanine catabolic pathway21. Microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 (MPGES-1), a member of the MAPEG family, is implicated in the biosynthesis of prostaglandin E2—a metabolite of arachidonic acid—involved in several biological functions. MPGES-1 catalyzes the terminal step of prostaglandin E2 synthesis through a GSH-dependent isomerization reaction22. MPGES1 have a key role in inflammatory diseases and is high upregulated in tissues during inflammation and overexpressed in tumors23.

GST non-enzymatic functions

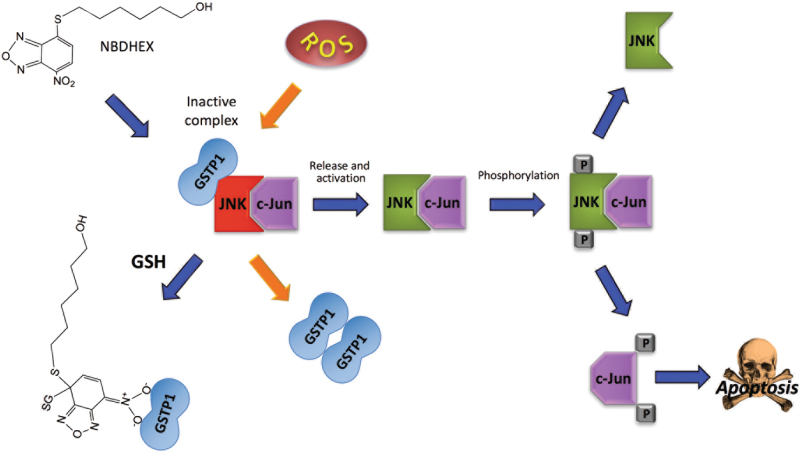

GSTs are also implicated as modulators of signal transduction pathways implicated in cell survival and apoptosis, where they control the activity of members of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family24,25. In particular, GSTP1-1 is able to protect the tumor cells from apoptosis signals by inhibiting c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK)—a member of the MAPK pathway—non-catalytically, by direct protein–protein association25,26. In response to different extracellular stimuli, the complex may dissociate and JNK can phosphorylate c-Jun, a component of the activator protein-1 transcription factor. This in turn leads to the induction of AP-1-dependent target genes, involved in cell proliferation, DNA repair, and cell death27. Mechanistically, it has been observed that GSTP1-1 binds, in its monomeric form, both c-Jun and JNK, thus forming an heterotrimeric complex that inhibits the phosphorylation of c-Jun by JNK. The dissociation of the enzyme from JNK also results in the dimerization of GSTP1-1 (Fig. 4)26,28. Furthermore, GSTP1-1 has also been shown to bind and inhibit tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2), an upstream activator of JNK, thus blocking the MAPK/JNK signaling cascade at multiple levels29. A detailed analysis of complex formation suggested that GSTP1-1 engages TRAF2 both through its G and H sites. However, and interestingly, data also suggested that while GSTP1-1 engages TRAF2 in its dimeric form, only one monomer is involved in binding and therefore the other may still be catalitically competent30. Finally, a cell cycle-dependent variation of the amount of GSTP1-1-TRAF2 complex existing in cells was detected, with a maximum in G0/G1 and a strong decrease in S, G2, and M phases.

Fig. 4. Role of GSTP1-1 in JNK signaling pathway.

Monomeric GSTP1 protects tumoral cells from apoptosis by inhibition of the JNK signaling pathway through the formation of a GSTP1-JNK-cJun complex that hampers c-Jun phosphorilation. Under stress conditions, GSTP1 may dissociate from the complex and dimerize, thus enabling JNK to phosphorilate c-Jun. This event may also be triggered by the GST inhibitor NBDHEX which binds GSTP1 and induces its release from the complex

GSTs gene polymorphisms and correlation to diseases

GSTs are represented—and expressed with unique patterns in each organ—in the human genome by multiple genes that are located in class-specific clusters on different chromosomes31–33. Several of these genes are polymorphic, resulting in phenotipic variants of GSTs. Genetic polymorphisms are heritable changes in DNA sequences as consequence of single-nucleotide polymorphisms or stable point mutations that may partially alter enzyme activity, or large deletions in coding sequences resulting in a null phenotype24,34. The main gst genes described as polymorphic are those coding for GSTM1-1, GSTT1-1 and GSTP1-1. The most common polymorphisms of GSTM1-1 and GSTT1-1 gene loci consist in the complete deletion of the genes. Furthermore, polymorphisms were also observed in other isoenzymes of the mu class: i.e. GSTM3-3 and GSTM4-4. As to the pi class, GSTP1-1 point mutations in both exon 5 (codon 105) and exon 6 (codon 114) were observed and shown to have an impact on the enzymatic activity32. Polymorphisms are also present in GSTs of the alpha class and omega class, with the isoenzymes GSTA1-1, GSTA2-2 and GSTO1-1 and GSTO2, respectively32.

Numerous studies centred on GST gene polymorphisms as factors modulating the risk of developing cancer32. In particular, GSTT1-1 and GSTM1-1 null genotypes, as well as GSTP1-1 variants, were studies and showed a positive correlation with cancer risk (Table 1)24,32,35–42. More recently, a meta-analysis study linked GSTT1-1 null polymorphism with an increased risk of coronary heart disease43. In addition, a significant correlation between GSTA1-1 and GSTT1-1 particular genotype combinations and the risk of psoriasis was observed44.

Table 1.

GST allelic variants associated with cancer risk and other diseases

| Gene | Allelic variant | Modification | OMIM number | Diseases | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSTM1 | GSTM1*O | Gene deletion | 138350 | Uterine leiomyoma, hypertension, oral leukoplakia, prostate cancer, chronic myeloid leukemia, breast cancer, epilepsy | 35–37, 39–41, 61 |

| GSTT1 | GSTT1*O | Gene deletion | 600436 | Uterine leiomyoma, hypertension, oral leukoplakia, brain tumour, breast cancer, coronary heart disease, psoriasisa, epilepsy | 35–38, 40,43, 44 |

| GSTP1 | GSTP1*B | Ile105Val | 134660.0002 | chronic myeloid leukemia, Parkinson’s disease, Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 39,56, 66 |

| GSTP1*C | Ile105Val/Ala114Val | 134660.0003 | Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease | 52, 56 | |

| GSTP1*D | Ala114Val | — | Brain tumour, Parkinson’s disease | 38, 56 | |

| GSTA1 | GSTA1*B | -69(C/T), mutation promoter | 138359 | Psoriasisb | 44 |

| GSTO1 | GSTO1*B | Glu155 deletion | 605482 | Alzheimer’s disease | 53 |

| GSTO2 | GSTO2*B c | Asn142Asp | 612314 | Breast cancer | 42 |

| GSTO2*C c | Ala183Gly | — | Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 | 65 |

OMIM Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man

a in association with GSTA1*A

b in association with GSTT1*A

c Allelic variants were identified as B and C in this work following the nomenclature by Townsend and Tew34

Notably, GST variants have the ability to influence response to drugs and environmental stresses32,45. For instance, it has been recently observed that in prostate cancer patients, polymorphism in GSTM3-3 may contribute to resistance to hormonal therapy through oxidative stress45. Indeed, in several studies it has been proposed that GST polymorphisms may be used as biomarkers for prognosis in cancer patients39,45.

Neurodegenerative diseases

GST polymorphisms have also been associated with neurodegenerative conditions including Alzhaimer and Parkinson diseases (Table 1)46,47. Oxidative stress is one of the events that possibly contributes to the development and progression of neurodegenerative disorders48,49. Oxidative stress is caused by an overproduction of oxidants or unbalanced defence mechanisms played by antioxidants and their related enzymes. One example is the dysregulation of GSH homeostasis and alterated levels or functions of GSTs (both decrease or increase)48,49. In the nervous system, the role exerted by GSH and its related enzymes is particularly relevant since neurons are highly sensitive to oxidative stress50.

Alzhaimer’s disease

Alzhaimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disease characterized by the pathological accumulation of β-amyloid peptides and neurofibrillary tangles into the brain, that usually starts slowly and gets worse over time up to dementia. Several studies have analyzed GST status in AD patients. In particular, reduced GST activity as compared to control subjects was described in all brain areas and ventricular CSF in postmortem AD patients, suggesting a role of these enzymes in the pathogenesis of the disease51. A significant presence of a GSTP1-1 allelic variant (the GSTP1*C allelic variant) was found in late-onset AD patients52. It has been proposed that the allelic variant might influence the stability of GSTP1-1/JNK complex and consequently JNK activity, depending on the redox status of the cell. Recent results also suggested that an uncommon polymorphic variant of GSTO1-1—the GSTO1*E155del variant—was associated with AD risk. It was shown that the deletion of E155 in GSTO1-1 has a significant effect on enzymatic stability and may consequently alter the physiologic role of the enzyme in the brain regions53.

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a long-term neurodegenerative disorder that affects the motor system, characterized primarily by the death of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and the presence of intracellular aggregates of misfolded α-synucleine (Lewy bodies) in the surviving neurons54,55. In addition to movement disorder, different non-motor symptoms such as dementia, psychosis and depression are observed in patients, which increase in late stages of disease. A correlation between severe reduction of GSH levels and PD onset was recently proposed50. Furthermore, several studies were conducted on various classes and isoforms of GSTs to obtain informations about their association with increased risk for the development of the disease47,50. In a proteomic study on postmortem samples of PD patients it was shown that GSTP1-1 levels are increased in PD patients at advanced stages. A role of the enzyme in modulating stress responses by controlling JNK activity was also proposed56, 57. Studies on GSTO1-1 also suggested a protective effect of this enzyme on PD, exerted through the inhibition of the active form of interleukin-1β (IL-1 β) which is a critical factor in inflammatory response47,58.

Epilepsy

Epilepsy is a disease of the brain, the distinctive characteristic of which is a predisposition to generate unprovoked seizures59. The association between polymorphisms of GST genes and the risk of epilepsy has been investigated in several studies60–62. In patients with progressive myoclonus epilepsy, a GSTT1-null genotype has been associated with increased risk of developing the disease where it might contribute to enhanced susceptibility to oxidative stress60. Different results were obtained in other group of patients61. In this study both GSTM1 and GSTT1 null genotypes were analysed to evaluate the effects on epilepsy risk susceptibility. The results obtained revealed that GSTM1 null genotype and not GSTT1 null genotype is significantly associated with epilepsy and possibly involved in the development of the disease. GSTs are also involved in antiepileptic drug resistance. It has also been observed a correlation between high levels of GSTP1-1 in the brain and medical intractability, suggesting that the enzyme may contribute to resistance to antiepileptic drug treatment62.

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2

Spinocerebellar ataxia type 2—a genetic neurodegenerative disorder due to a CAG repeat expansion mutation in the ATXN2 gene coding for the protein ataxin-263—has been associated to oxidative stress, in particular due to alterations in the enzymatic activity of antioxidant enzymes including GSTs64. In a case-control study, it was observed a significant increase in GST activity in affected individuals relative to controls. More recently, spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 has also been linked to the presence of a transition polymorphism in the GSTO2 gene (rs2297235 “A183G”) which significantly correlates with the age at disease onset; the presence of at least one G allele causing an anticipated disease onset of 5.4 years65.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a fatal progressive neurological disorder characterized by muscle paralysis caused by the degeneration of motor neurons in the brain, brainstem and spinal cord. High levels of oxidative stress may contribute to ALS onset, increasing motoneurons death, and heavy metals may be a cause for the increase of ROS. Under this frame, it was observed that the association between lead exposure and ALS risk may correlate with particular GSTP1 gene polymorphisms66. Indeed, the expression of the GSTP1-1 variant Ile105Val is able to increase the effect of lead on the development of ASL66. Finally, a possible effect of the GSTO1 and GSTO2 loci on the age at onset of ALS was also reported67.

ROLE of GSTs in cancer drug resistance

Multidrug resistance is an event involving several different mechanisms68. In a broad variety of cancers, GSTs are involved in the resistance to several anticancer drugs by their conjugating activity (some examples are reported below). In cancer cells, GSTs often show high levels of expression when compared to normal cells1,69. Overexpression of GSTs may contribute to increase detoxification of anticancer drugs68. Synergistic interactions between GSTs and efflux pumps have also been observed in several studies68,70. Indeed, drug resistance is also related to increase discharge (efflux) of anticancer drugs due to the overexpression of the efflux transporters. GS-conjugates are actively transported out of cells by efflux transporters including MRP1 and P-glycoprotein belonging to the superfamily of ATP-binding cassette transporters70–72. Therefore both GST and efflux pumps overexpression may confer high levels of resistance to the cytotoxic action of several antineoplastic drugs. In addition, GSTs are also involved in conferring multidrug resistance with a non-catalytic mechanism through their inhibition of the JNK signaling pathway, an event that protects tumoral cells from apoptosis, as it will be detailed later.

A few examples of the activities played by GSTs on antineoplastic agents and their contribution to drug resistance in cancer are the following:

Cisplatin

Platinum chemotherapeutic drugs are among the most extensively used anticancer agents73. Cisplatin is one of the most efficacious, and, although its use produces several side-effects, it is still a drug of choise for treating a number of solid cancer74,75. It interacts with DNA to form adducts—such as DNA–DNA and DNA–proteins crosslinks—which activate several signal transduction pathways that trigger cell death74,76. Several and unrelated mechanisms are responsible for drug resistance to cisplatin. One of them is the ability of GSH to bind and inactivate the anti-cancer drug76. High concentrations of the thiol were detected in the presence of cisplatin, decreasing the levels of the available drug. Although the conjugation of GSH to cisplatin also happens non-enzymatically, GSTs can catalyse it (Fig. 3d). It has been observed that enzymatic inactivation of cisplatin by GSTP1-1 contributes significantly to drug-resistance77.

Busulfan

Busulfan is an alkylating agent widely used in myeloablative conditioning regimens before bone marrow or hematopoietic stem cell transplantations78. High-dose busulfan treatment is correlated with drug-related events such as cataracts and hepatic sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. The toxicity of busulfan is caused by its irreversibile glutathionylation played by GSTs. GSTs, primarily GSTA1-1, are involved in the first step of the metabolic pathway of busulfan79,80. GSTs catalyse busulfan conjugation to GSH, yielding glutathionyl-tetrahydrothiophene (GS-THT+; Fig. 3e). Then, GS-THT+ is metabolized via a β-elimination reaction to obtain γ-glutamyl-dehydroalanyl-glycine (EdAG), which reacts with a second GSH to form lanthionine GSG, a non-reducible analogue of GSH. Lanthionine GSG in turn, forms an irreversible mixed disulfide with protein thiols that could lead to dysregulation of proteins that are normally regulated by reversible glutathionylation81.

Dichloroacetate

Dichloroacetate (DCA), a product of water chlorination, is considered for the treatment of several disorders including genetic mitochondrial diseases and some hyperproliferative conditions82. DCA inhibits mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase that inactives the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. The maintenance in the active state of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex – that oxidizes pyruvate to acetyl CoA – stimulates oxidative phosphorylation. In tumor cells, a switch of glucose metabolism from aerobic glycolysis to oxidation leads to inhibition of proliferation and induction of caspase-mediated apoptosis82. A GST of the zeta class (GSTZ1-1) is involved in the metabolism of dichloroacetate83,84. GSTZ1-1 is a bifunctional enzyme that, acting as maleylacetoacetate isomerase, is also involved in the metabolic degradation of phenylalanine and tyrosine83. The enzyme dechlorinates DCA to glyoxylate inactivating it (Fig. 3f) and subsequently may provide resistance to DCA treatment. Intriguingly, it has also been observed that DCA is able to inhibit GSTZ1-185. It has been observed that repeated doses of DCA resulted in loss of GSTZ1-1 protein and activity, probably due to post-translationally modifications of the enzyme85. Recently, it has also been demonstrated that abnormal regulation of GSTZ1-1 expression in cancer cells may influence DCA metabolism, and consequently lead to an altered therapeutic response84.

GST inhibitors

Inhibitors of GSTs may increase the sensitivity of cancer cells to antitumor drugs and thus they may be used for several therapeutic applications86. For this reason, a remarkable number of inhibitors for GSTs have been synthesized as well as GSH analogues with better specificities and reduced toxicities69,87. Furthermore, different natural inhibitors found in plants were also discovered and investigated24,88. Here we describe some of the most characterized examples:

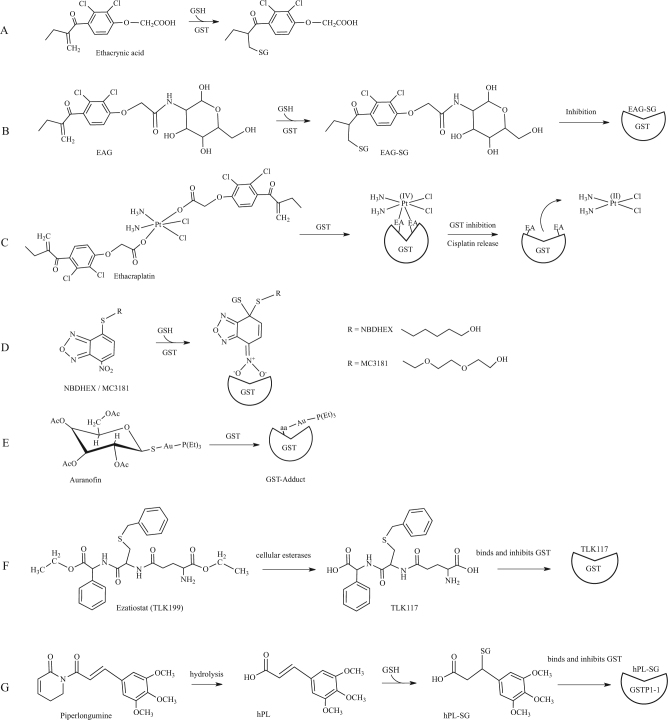

Ethacrynic acid and analogues

Ethacrynic acid (EA)—an α,β-unsaturated ketone used as diuretic drug—is a common substrate/inhibitor of several GSTs (Fig. 5a)68,89. EA is active against human tumor cells in particular through its inhibitory activity on GSTP1-1 by covalent binding of the GSH-EA complex. However, despite the good pharmacological properties shown by this molecule on several cancers, its use in the clinic is problematic because of its strong diuretic properties. For this reasons, several laboratories have developed EA analogues with improved properties. For example, EA was conjugated to 2-amino-2-deoxy-d-glucose (EAG)90, obtaining an adduct with significant anticancer activity such as EA but without the undesired diuretic activity90. EAG is structurally similar to EA, is conjugated by GSH and the adduct inhibits GSTP1-1 (Fig. 5b). More recently, the anticancer activity of new EA derivates has been tested in antiproliferative assays on two different tumoral cell lines91. These new molecules showed an efficient anti-proliferative activities against human cancer cells emphasizing the potential of them as novel anticancer agents.

Fig. 5. GST inhibitors.

a GST-catalyzed conjugation of ethacrynic acid; b A conjugate of ethacrynic acid and glucosamine (EAG) reacts with GSH and inhibits GSTs; c Ethacraplatin is a Pt(IV)-complex compound which contains two ethacrynic acid moieties. When exposed to GSTs, this compound inhibits the enzyme and liberates cisplatin; d NBDHEX and its MC3181 derivative are GST inhibitors that bind the enzyme H-site and are conjugated by GSH leading to the formation of a stable σ complex; e Auranofin structure and its inhibitory effect on GSTs; f Ezatiostat (TLK199) is a GSH analogue that exerts its inhibitory effects on GSTs through G-site binding; g Piperlongumine is hydrolized inside cells and forms a conjugate with GSH that exerts inhibition of GST acitivity

Ethacraplatin

Ethacraplatin is a bifunctional drug developed to overcome GST mediated cisplatin resistance92. Ethacraplatin – a dual-threat platinum (IV) prodrug – is a cisplatin molecule coordinated to two ethacrynic acid ligands which is able to inhibit irreversibly GSTP1-1 enzymatic activity being reduced and cleaved as a consequence of binding (Fig. 5c)73,93. This in turn permits to increase the diffusion of Pt ions and reverts platinum drug resistance93. Ethacraplatin is also able to revert cisplatin resistance in microsomal GST1-1 overexpressing cells94. Recently, a new potential drug preparation was developed encapsulating ethacraplatin in nanoscale micelles. This significantly enhanced the accumulation of cisplatin in tumor cells, increasing efficacy in cisplatin resistant cells and decreased tossicity95.

NBDHEX

6-(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-ylthio)hexanol (NBDHEX) is a highly efficient inhibitor of GSTP1-1 and other GSTs, which triggers apoptosis in several cancer cells (Fig. 4)96,97. As already mentioned, GSTP1-1 is over-expressed in several cancers where it protects cells from cell death by inhibiting the activity of JNK or its upstream activation. Indeed, the formation of both GSTP1-JNK and GSTP1-1-TRAF2 complexes were described in vivo. NBDHEX binds the GSTP1-1 H-site and forms a complex with GSH, inactivating the enzyme (Figs. 4 and 5d)98. Importantly, NBDHEX is also able to dissociate GSTP1-1 from its complexes with both JNK and TRAF2, thus enabling their activation99. Drug combination studies showed that NBDHEX is significantly active on cisplatin-resistant human osteosarcoma cells77.

Oner of the problems in the clinical use of NBDHEX may arise from its lack of specificity for GSTP1-1. For example this drug displays a much higher affinity for GSTM2-2 than for GSTP1-198. For this reason, several novel NBDHEX analogues, with improved selectivity for GSTP1-1, have been synthesized and characterized to obtain new therapeutic opportunities for the treatment of drug resistant tumors including human melanoma100,101. Among them, the MC3181 derivative was recently found to be extremely efficient in blocking cancer growth and metastasis in a xenograft mouse model of vemurafenib resistant melanoma (Fig. 5d)102.

Auranofin

Auranofin is an antiarthritic gold phosphine compound that also exhibits anticancer effects similar to those of cisplatin. Unlike cisplatin and similarly to other antiarthritic gold drugs, auranofin appears to exert its activity through inhibition of enzyme activities rather than DNA damage. This different molecular mechanism would allow to overcome cell resistance against platinum agents. Recent studies suggested that one of the enzymes inhibited by auranofin is GSTP1-1 (Fig. 5e)103. Notably, similar inhibitions were observed both with the wild type enzyme and its cysteine mutants, suggesting that thiol conjugation is dispensable for GST inactivation by auronofin in contrast to other described targets103. Therefore, future research efforts will be necessary to clarify the mechanism of enzyme inhibition played by auranofin on GSTs. Finally, it is of notable interest that the well-described antiplasmodial effects of auranofin may be possibly correlated to GST inhibition.

Glutathione analogues

Different GST inhibitors have been conceived based on the structure of the GSH moiety. The tripeptide GSH is the most abundant low molecular weight thiol in the cell, and it is found is almost all eukaryotes and several prokaryotes104. It has been observed that the increase of GSH levels has a cytoprotective effect. Nevertheless, since GSH cannot be administered directly—because of its insufficient absorption, stability and solubility—analogues have been obtained, through modifications at the γ-glutamyl, cysteine and glycine moieties, and/or the functionalisation of the central cysteine, that are able to inhibit the activity of GSTs69,87,105. A well-characterized example is ezatiostat (TLK199)—a GSH peptidomimetic molecule—designed to display enhanced cellular uptake and whose metabolites bind the G-site of GSTP1-1 causing enzyme inhibition. Among them, TLK117 results from de-esterification of TLK199 and is the most selective GSTP1-1 inhibitor (Fig. 5f). Its interaction with the enzyme results in JNK activation and c-Jun phophorilation106. This compound was found efficaceous in the treatment of myelodisplastic syndrome and its investigation has so far moved up to phase I-IIa clinical trials. Moreover, it has been observed that cyclic GSH, which is less sensitive to the effects of several degradative enzymes, appears to have toxic activity on cancer cell lines87.

Piperlongumine

Piperlongumine (PL) is an alkaloid isolated from Piper species, commonly used in traditional medicine – in particular in Asia and Latin America – that in recent years has been extensively studied because of its anti-cancer potential, being able to inhibit proliferation in several cancer cell lines107. It has been observed that the anti-cancer effects are associated with an increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reduction of GSH levels. Recently, it has been demonstrated that PL inhibits GSTP1-1 by directly binding the enzyme88. A structural model of the interaction suggests that the active molecule is a hydrolyzed form of PL (hPL) which forms a complex with GSH in the enzyme active site. Authors proposed a model wherein PL enters the cell, is hydrolyzed in its active form (hPL) with subsequent formation of a hPL:GSH complex that binds the active site of GSTP1-1 causing its inhibition (Fig. 5g). The following reduction of GSH cell concentration and increase of ROS levels also contributes to cell death88.

Pro-drugs

Prodrugs are pharmacologically inactive molecules in vitro that are converted into their active parent drugs in vivo after chemical modifications and/or enzymatic reactions. They are often designed to improve the bioavailability of active drugs by increasing their amount in target cells and reducing off-target effects. The overexpression of GSTs in cancer cells offers unique opportunities for prodrug therapy108. Indeed the activation of prodrugs in GST overexpressing cells may lead to high concentrations of an active drug, as compared to normal cells with moderate enzyme levels. Essentially, two groups can be distinguished: (i) molecules containing GSH or GSH-like moiety and (ii) molecules whose enzymatic activation occurs through a GSH-conjugate intermediate109. Important examples are detailed below.

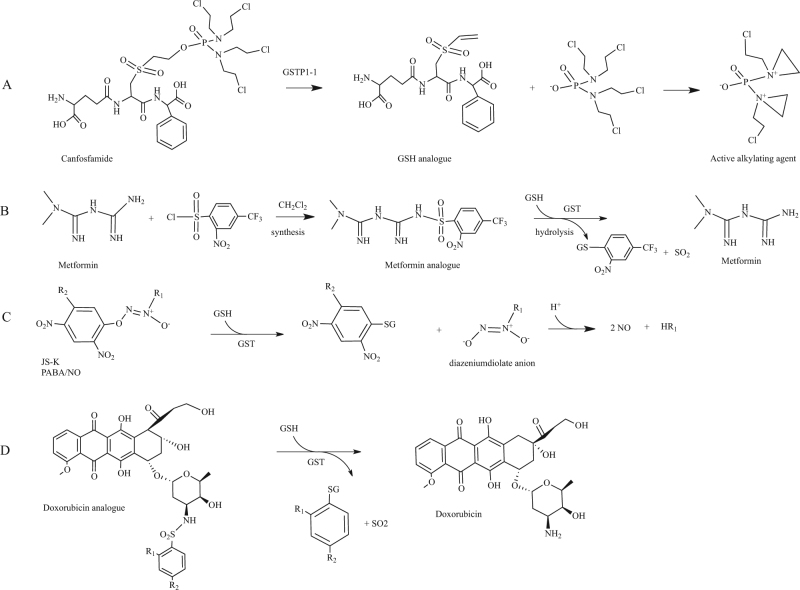

Canfosfamide

Canfosfamide, also known as TLK286, is a GSH analogue activated by GSTP1-1 into a GSH derivative and phosphorodiaminate, an alkylating metabolite that forms covalent linkages with DNA (Fig. 6a)110,111. TLK286 clinical effects were investigated in the last decade in phase II and phase III trials for the treatment of drug-resistant ovarian cancer112,113. A phase I-IIa clinical trial in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel investigated the effect of canfosfamide in advanced non-small cell lung cancer114.

Fig. 6. GST prodrugs.

a Bioconversion of canfosfamide in an active alkilating metabolite played by GSTP1-1; b synthesis and bioconversion played by GST of a metformin sulfonamide prodrug; c GSH conjugation with nitric oxide releasing agents to form diazeniumdiolate anion and subsequent release of two NO molecules; d Release of active doxorubicin by GST sulfomidase activity played on nitrobenzenesulfonyl analogues

Metformin analogues

Metformin is the most used drug in the treatment of type II diabetes in the world. The drug reduces hepatic glucose production, enhances glucose uptake in the peripheral tissues and increases insulin sensitivity115. Indeed metformin inhibits the mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation complex I, leading to increased cellular AMP levels and subsequent stimulation of AMPK, an enzyme that plays key roles in the regulation of cellular energy homeostatis. However, metformin also exerts anticancer effects and is thought to do this through both AMPK-dependent and AMPK-independent mechanisms116. Several studies showed evident association between type II diabetes and cancer, in particular in liver and pancreas, organs persistently exposed to high levels of endogenous insulin117–119. Although metformin is extremely efficient, its absorbtion is poor and variable. On the other hands, great amounts of drug cause gastrointestinal distress that is not always well tolerated by patients. To enhance the oral absorbtion of the drug, metformin prodrugs were developed with improved permeability across the lipid membrane120. The first developed metformin prodrug, namely its cyclohexyl sulfenamide derivative, was in part activated on the apical side of the enterocytes with consequent decrease of absorbtion121. To overcome the problem, prodrugs activated only after oral absorption were developed. Since high levels of GSTs are expressed in the hepatocytes and it has previously been demonstrated that GSTs display sulfonamidase activity, three sulfonamide prodrugs of metformin were designed and synthesized120. GSTs catalyze the GSH-mediated hydrolysis of sulphonamide bonds to form the corresponding amine108. For one of these derivatives, authors obtained interesting results. GST was able to convert the derivative into the parent drug in a quantitative manner (Fig. 6b).

Nitric oxide prodrugs

Nitric oxide (NO) is involved in several key physiological and pathological processes122. In cancer cells, high concentration of NO can damage various macromolecules such as nucleic acids and proteins and finally trigger apoptosis. NO-releasing agents, such as JS-K (O2-(2,4-dinitrophenyl)-1-[(4-ethoxycarbonyl)piperazin-1-yl]diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate)123 and PABA/NO (O2-[2,4-dinitro-5-(N-methyl-N-4 carboxyphenylamino)phenyl] 1-N,N-dimethylamino)diazen-1-ium-1,2-diolate)124, are able to induce differentiation and cell death in a variety of cancer cells through GSH consumption, DNA synthesis inhibition and inhibition of enzymes involved in the defense against cell damage. GSTs catalyse the reaction of JS-K or PABA/NO with GSH to form a diazeniumdiolate anion that spontaneously decomposes, producing two equivalents of NO (Fig. 6c). To improve drug properties—such as stability and anticancer activity—of diazeniumdiolate-based NO donors, a number of new molecules were synthesized and biologicaly evaluated109,125,126.

Doxorubicin analogues

Doxorubicin (DOX) is a common topoisomerase II inhibitor widely used in the treatment of solid tumors and malignant hematologic diseases. DOX is a highly toxic molecule and induces drug resistance due to the overexpression of ABCB1 efflux pump and other related proteins127. Microsomal GST1 (MGST1) and GSTP1-1, which are frequently overexpressed in cancer cells, contribute to DOX resistance. To overcome drug resistance and enhance its cytotoxicity, two derivatives of DOX were synthesized incorporating a sulfonamide moiety: 4-mononitrobenzenesulfonyl DOX (MNS-DOX) and 2,4-dinitrobenzenesulfonyl DOX (DNS-DOX)94. As reported above, GSTs display sulfonamidase activity. MNS-DOX and DNS-DOX were converted by MGST1 and GSTP1-1 via sulfonamide cleavage into the active parent drug (Fig. 6d). Notably, the less reactive MNS-DOX was more effective in MGST1 overexpressing cells than DNS-DOX. A new derivate of DOX, 4-acetyl-2-nitro-benzenesulfonyl doxorubicin (ANS-DOX) was synthesized and shown to be converted into DOX by MGST1 and GSTA1-1, whereas no activity was observed for GSTP1-1128. ANS-DOX showed to be toxic in GSTA1-1 overexpressing cancer cells. Collectively, these investigations suggested the plausibility of modulating the rate of drug release as well as specifically targeting different GSTs by modifying the sulfonamide moiety128.

Conclusions

Recent advances in this field have highlighted the importance of GST activities and the role that these enzymes play in diverse cellular processes as well as in conferring resistance to chemotherapy. Within this context, it is not surprising that a great deal of inhibitors and pro-drugs targeting GSTs have been synthesized and tested so far, with new scaffolds or analogues being reported every year. Some of these molecules have also entered clinical trials and we will possibly welcome in the future the approval of a GST inhibitor or pro-drug for the treatment of patients. While surveying the literature in preparation of this manuscript we have also noticed and reported an increasing interest in the role that GSTs play in neurodegeneration, where isozymes belonging to the family may be either up-regulated, mutated or absent, according to the different diseases. Research in this field is particularly lively and holds the promise to define specific GSTs, or specific GST polymorphic forms as possible pharmacological targets.

Up to know, the majority of established and newly synthesized GST inhibitors have been primarily tested for their cytotoxic effect in cancer cell lines and mouse xenograft models, showing promising activities. One of the problems that have emerged, especially when many of these drugs have been tested in vitro for their inhibition properties, is their lack of specificity. Indeed, while in many cases it would be desirable or crucial to specifically target a particular GST isozyme or polymorphic form, this is hardly achievable with the molecules synthesized and investigated so far. We anticipate that the search for more specific GST inhibitors will be the main goal of future research in this field.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC) (IG2014-15197 to L.F.) and by grants from the University of Chieti-Pescara “G. d’Annunzio” (to N.A. and L.F.).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hayes JD, Flanagan JU, Jowsey IR. Glutathione transferases. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2005;45:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.45.120403.095857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sheehan D, Meade G, Foley VM, Dowd CA. Structure, function and evolution of glutathione transferases: implications for classification of non-mammalian members of an ancient enzyme superfamily. Biochem. J. 2001;360:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3600001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allocati N, Federici L, Masulli M, Di Ilio C. Glutathione transferases in bacteria. FEBS J. 2009;276:58–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Allocati N, Federici L, Masulli M, Di Ilio C. Distribution of glutathione transferases in Gram-positive bacteria and Archaea. Biochimie. 2012;94:588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2011.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu B, Dong D. Human cytosolic glutathione transferases: structure, function, and drug discovery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;33:656–668. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2012.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oakley A. Glutathione transferases: a structural perspective. Drug. Metab. Rev. 2011;43:138–151. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2011.558093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morel F, Aninat C. The glutathione transferase kappa family. Drug. Metab. Rev. 2011;43:281–291. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2011.556122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morgenstern R, Zhang J, Johansson K. Microsomal glutathione transferase 1: mechanism and functional roles. Drug. Metab. Rev. 2011;43:300–306. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2011.558511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li YS, Hung SC, Wei YH, Tarng DC. GST M1 polymorphism associates with DNA oxidative damage and mortality among hemodialysis patients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009;20:405–415. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008020227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayes JD, et al. Regulation of rat glutathione S-transferase A5 by cancer chemopreventive agents: mechanisms of inducible resistance to aflatoxin B1. Chem. Biol. Interact. 1998;111-112:51–67. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2797(97)00151-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wild CP, Turner PC. The toxicology of aflatoxins as a basis for public health decisions. Mutagenesis. 2002;17:471–481. doi: 10.1093/mutage/17.6.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dohnal V, Wu Q, Kuca K. Metabolism of aflatoxins: key enzymes and interindividual as well as interspecies differences. Arch. Toxicol. 2014;88:1635–1644. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1312-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singhal SS, et al. Antioxidant role of glutathione S-transferases: 4-Hydroxynonenal, a key molecule in stress-mediated signaling. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2015;289:361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minko IG, et al. Chemistry and biology of DNA containing 1,N(2)-deoxyguanosine adducts of the alpha,beta-unsaturated aldehydes acrolein, crotonaldehyde, and 4-hydroxynonenal. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009;22:759–778. doi: 10.1021/tx9000489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dalleau S, Baradat M, Gueraud F, Huc L. Cell death and diseases related to oxidative stress: 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) in the balance. Cell. Death Differ. 2013;20:1615–1630. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y, Huycke MM, Herman TS, Wang X. Glutathione S-transferase alpha 4 induction by activator protein 1 in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35:5795–5806. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vatsyayan R, Lelsani PC, Awasthi S, Singhal SS. RLIP76: a versatile transporter and an emerging target for cancer therapy. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010;79:1699–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faroon O, et al. Acrolein health effects. Toxicol. Ind. Health. 2008;24:447–490. doi: 10.1177/0748233708094188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henning RJ, Johnson GT, Coyle JP, Harbison RD. Acrolein can cause cardiovascular disease: a review. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 2017;17:227–236. doi: 10.1007/s12012-016-9396-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens JF, Maier CS. Acrolein: sources, metabolism, and biomolecular interactions relevant to human health and disease. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008;52:7–25. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.200700412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deponte M. Glutathione catalysis and the reaction mechanisms of glutathione-dependent enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1830:3217–3266. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pettersson PL, Thoren S, Jakobsson PJ. Human microsomal prostaglandin E synthase 1: a member of the MAPEG protein superfamily. Methods Enzymol. 2005;401:147–161. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)01009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Psarra A, Nikolaou A, Kokotou MG, Limnios D, Kokotos G. Microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase-1 inhibitors: a patent review. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2017;27:1047–1059. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2017.1344218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh S. Cytoprotective and regulatory functions of glutathione S-transferases in cancer cell proliferation and cell death. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2015;75:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laborde E. Glutathione transferases as mediators of signaling pathways involved in cell proliferation and cell death. Cell. Death Differ. 2010;17:1373–1380. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2010.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adler V, et al. Regulation of JNK signaling by GSTp. EMBO J. 1999;18:1321–1334. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karin M, Gallagher E. From JNK to pay dirt: jun kinases, their biochemistry, physiology and clinical importance. IUBMB Life. 2005;57:283–295. doi: 10.1080/15216540500097111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernardini S, et al. Role of GST P1-1 in mediating the effect of etoposide on human neuroblastoma cell line Sh-Sy5y. J. Cell. Biochem. 2002;86:340–347. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Y, et al. Human glutathione S-transferase P1-1 interacts with TRAF2 and regulates TRAF2-ASK1 signals. Oncogene. 2006;25:5787–5800. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Luca A, et al. The fine-tuning of TRAF2-GSTP1-1 interaction: effect of ligand binding and in situ detection of the complex. Cell. Death Dis. 2014;5:e1015. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2013.529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wormhoudt LW, Commandeur JN, Vermeulen NP. Genetic polymorphisms of human N-acetyltransferase, cytochrome P450, glutathione-S-transferase, and epoxide hydrolase enzymes: relevance to xenobiotic metabolism and toxicity. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 1999;29:59–124. doi: 10.1080/10408449991349186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Pietro G, Magno LA, Rios-Santos F. Glutathione S-transferases: an overview in cancer research. Expert. Opin. Drug. Metab. Toxicol. 2010;6:153–170. doi: 10.1517/17425250903427980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Board PG, Menon D. Glutathione transferases, regulators of cellular metabolism and physiology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1830:3267–3288. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Townsend D, Tew K. Cancer drugs, genetic variation and the glutathione-S-transferase gene family. Am. J. Pharmacol. 2003;3:157–172. doi: 10.2165/00129785-200303030-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mostafavi SS, et al. Impact of null genotypes of GSTT1 and GSTM1 with uterine leiomyoma risk in Iranian population. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2016;42:434–439. doi: 10.1111/jog.12924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eslami S, Sahebkar A. Glutathione-S-transferase M1 and T1 null genotypes are associated with hypertension risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 studies. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2014;16:432. doi: 10.1007/s11906-014-0432-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He P, Wei M, Wang Y, Liu Q. Associations among glutathione S-transferase T1, M1, and P1 polymorphisms and the risk of oral leukoplakia. Genet. Test. Mol. Biomark. 2016;20:312–321. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2015.0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geng P, et al. Genetic contribution of polymorphisms in glutathione S-transferases to brain tumor risk. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016;53:1730–1740. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weich N, et al. GSTM1 and GSTP1, but not GSTT1 genetic polymorphisms are associated with chronic myeloid leukemia risk and treatment response. Cancer Epidemiol. 2016;44:16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2016.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campos, C. Z. et al. Glutathione S-transferases deletions may act as prognosis and therapeutic markers in breast cancer. Clin. Exp. Med. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Malik SS, et al. Genetic polymorphism of GSTM1 and GSTT1 and risk of prostatic carcinoma - a meta-analysis of 7,281 prostate cancer cases and 9,082 healthy controls. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2016;17:2629–2635. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.4.2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu YT, et al. Genetic polymorphisms in Glutathione S-transferase Omega (GSTO) and cancer risk: a meta-analysis of 20 studies. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:6578. doi: 10.1038/srep06578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song Y, et al. Glutathione S-transferase T1 (GSTT1) null polymorphism, smoking, and their interaction in coronary heart disease: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Heart Lung. Circ. 2017;26:362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hruska P, et al. Combinations of common polymorphisms within GSTA1 and GSTT1 as a risk factor for psoriasis in a Central European population: a case-control study. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2017;31:e461–e463. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shiota M, et al. Gene polymorphisms in antioxidant enzymes correlate with the efficacy of androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer with implications of oxidative stress. Ann. Oncol. 2017;28:569–575. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdw646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Board PG, Menon D. Structure, function and disease relevance of Omega-class glutathione transferases. Arch. Toxicol. 2016;90:1049–1067. doi: 10.1007/s00204-016-1691-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar A, et al. Role of glutathione-S-transferases in neurological problems. Expert. Opin. Ther. Pat. 2017;27:299–309. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2017.1254192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson W, Wilson-Delfosse AL, Mieyal JJ. Dysregulation of glutathione homeostasis in neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients. 2012;4:1399–1440. doi: 10.3390/nu4101399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uttara B, Singh AV, Zamboni P, Mahajan RT. Oxidative stress and neurodegenerative diseases: a review of upstream and downstream antioxidant therapeutic options. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2009;7:65–74. doi: 10.2174/157015909787602823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mazzetti AP, Fiorile MC, Primavera A, Lo Bello M. Glutathione transferases and neurodegenerative diseases. Neurochem. Int. 2015;82:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lovell MA, Xie C, Markesbery WR. Decreased glutathione transferase activity in brain and ventricular fluid in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1998;51:1562–1566. doi: 10.1212/WNL.51.6.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bernardini S, et al. Glutathione S-transferase P1 *C allelic variant increases susceptibility for late-onset Alzheimer disease: association study and relationship with apolipoprotein E epsilon4 allele. Clin. Chem. 2005;51:944–951. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.045955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Piacentini S, et al. GSTO1*E155del polymorphism associated with increased risk for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease: association hypothesis for an uncommon genetic variant. Neurosci. Lett. 2012;506:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aarsland D, et al. Cognitive decline in Parkinson disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2017;13:217–231. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shi M, et al. Identification of glutathione S-transferase pi as a protein involved in Parkinson disease progression. Am. J. Pathol. 2009;175:54–65. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.081019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Castro-Caldas M, et al. Glutathione S-transferase pi mediates MPTP-induced c-Jun N-terminal kinase activation in the nigrostriatal pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 2012;45:466–477. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Laliberte RE, et al. Glutathione s-transferase omega 1-1 is a target of cytokine release inhibitory drugs and may be responsible for their effect on interleukin-1beta posttranslational processing. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:16567–16578. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211596200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fisher RS, et al. ILAE official report: a practical clinical definition of epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2014;55:475–482. doi: 10.1111/epi.12550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ercegovac M, et al. GSTA1, GSTM1, GSTP1 and GSTT1 polymorphisms in progressive myoclonus epilepsy: A Serbian case-control study. Seizure. 2015;32:30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chbili C, et al. Effects of glutathione S-transferase M1 and T1 deletions on epilepsy risk among a Tunisian population. Epilepsy Res. 2014;108:1168–1173. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2014.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shang W, et al. Expressions of glutathione S-transferase alpha, mu, and pi in brains of medically intractable epileptic patients. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sun YM, Lu C, Wu ZY. Spinocerebellar ataxia: relationship between phenotype and genotype – a review. Clin. Genet. 2016;90:305–314. doi: 10.1111/cge.12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Almaguer-Gotay D, et al. Role of glutathione S-transferases in the spinocerebellar ataxia type 2 clinical phenotype. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014;341:41–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Almaguer-Mederos LE, et al. Association of glutathione S-transferase omega polymorphism and spinocerebellar ataxia type 2. J. Neurol. Sci. 2017;372:324–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2016.11.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Eum KD, et al. Modification of the association between lead exposure and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by iron and oxidative stress related gene polymorphisms. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 2015;16:72–79. doi: 10.3109/21678421.2014.964259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.van de Giessen E, et al. Association study on glutathione S-transferase omega 1 and 2 and familial ALS. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2008;9:81–84. doi: 10.1080/17482960701702553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sau A, Pellizzari Tregno F, Valentino F, Federici G, Caccuri AM. Glutathione transferases and development of new principles to overcome drug resistance. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2010;500:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gate L, Tew KD. Glutathione S-transferases as emerging therapeutic targets. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets. 2001;5:477–489. doi: 10.1517/14728222.5.4.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meijerman I, Beijnen JH, Schellens JH. Combined action and regulation of phase II enzymes and multidrug resistance proteins in multidrug resistance in cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2008;34:505–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Homolya L, Varadi A, Sarkadi B. Multidrug resistance-associated proteins: Export pumps for conjugates with glutathione, glucuronate or sulfate. Biofactors. 2003;17:103–114. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520170111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Keppler D. Export pumps for glutathione S-conjugates. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 1999;27:985–991. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(99)00171-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Johnstone TC, Suntharalingam K, Lippard SJ. The next generation of platinum drugs: targeted Pt(II) agents, nanoparticle delivery, and Pt(IV) prodrugs. Chem. Rev. 2016;116:3436–3486. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ho GY, Woodward N, Coward JI. Cisplatin versus carboplatin: comparative review of therapeutic management in solid malignancies. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016;102:37–46. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rathinam, R., Ghosh, S., Neumann, W. L., & Jamesdaniel, S. Cisplatin-induced apoptosis in auditory, renal, and neuronal cells is associated with nitration and downregulation of LMO4. Cell Death Discov. 1 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/cddiscovery.2015.52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Siddik ZH. Cisplatin: mode of cytotoxic action and molecular basis of resistance. Oncogene. 2003;22:7265–7279. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pasello M, et al. Overcoming glutathione S-transferase P1-related cisplatin resistance in osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:6661–6668. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bouligand J, et al. Induction of glutathione synthesis explains pharmacodynamics of high-dose busulfan in mice and highlights putative mechanisms of drug interaction. Drug. Metab. Dispos. 2007;35:306–314. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.012880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gibbs JP, Czerwinski M, Slattery JT. Busulfan-glutathione conjugation catalyzed by human liver cytosolic glutathione S-transferases. Cancer Res. 1996;56:3678–3681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Czerwinski M, Gibbs JP, Slattery JT. Busulfan conjugation by glutathione S-transferases alpha, mu, and pi. Drug. Metab. Dispos. 1996;24:1015–1019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Scian M, Atkins WM. The busulfan metabolite EdAG irreversibly glutathionylates glutaredoxins. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2015;583:96–104. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2015.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kankotia S, Stacpoole PW. Dichloroacetate and cancer: new home for an orphan drug? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1846:617–629. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Polekhina G, Board PG, Blackburn AC, Parker MW. Crystal structure of maleylacetoacetate isomerase/glutathione transferase zeta reveals the molecular basis for its remarkable catalytic promiscuity. Biochemistry. 2001;40:1567–1576. doi: 10.1021/bi002249z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jahn SC, et al. GSTZ1 expression and chloride concentrations modulate sensitivity of cancer cells to dichloroacetate. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2016;1860:1202–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2016.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.James MO, et al. Therapeutic applications of dichloroacetate and the role of glutathione transferase zeta-1. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016;170:166–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mahajan S, Atkins WM. The chemistry and biology of inhibitors and pro-drugs targeted to glutathione S-transferases. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:1221–1233. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4524-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wu JH, Batist G. Glutathione and glutathione analogues; therapeutic potentials. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1830:3350–3353. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2012.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Harshbarger W, et al. Structural and biochemical analyses reveal the mechanism of glutathione S-transferase Pi 1 inhibition by the anti-cancer compound piperlongumine. J. Biol. Chem. 2017;292:112–120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.750299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Townsend DM, Tew KD. The role of glutathione-S-transferase in anti-cancer drug resistance. Oncogene. 2003;22:7369–7375. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Punganuru SR, Mostofa AG, Madala HR, Basak D, Srivenugopal KS. Potent anti-proliferative actions of a non-diuretic glucosamine derivative of ethacrynic acid. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:2829–2833. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mignani S, et al. A novel class of ethacrynic acid derivatives as promising drug-like potent generation of anticancer agents with established mechanism of action. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016;122:656–673. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2016.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ang WH, et al. Synthesis and characterization of platinum(IV) anticancer drugs with functionalized aromatic carboxylate ligands: influence of the ligands on drug efficacies and uptake. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:8060–8069. doi: 10.1021/jm0506468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Parker LJ, et al. Studies of glutathione transferase P1-1 bound to a platinum(IV)-based anticancer compound reveal the molecular basis of its activation. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:7806–7816. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Johansson K, et al. Characterization of new potential anticancer drugs designed to overcome glutathione transferase mediated resistance. Mol. Pharmacol. 2011;8:1698–1708. doi: 10.1021/mp2000692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li S, et al. Overcoming resistance to cisplatin by inhibition of glutathione S-transferases (GSTs) with ethacraplatin micelles in vitro and in vivo. Biomaterials. 2017;144:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tentori L, et al. The glutathione transferase inhibitor 6-(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-ylthio)hexanol (NBDHEX) increases temozolomide efficacy against malignant melanoma. Eur. J. Cancer. 2011;47:1219–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Graziani G, et al. A new water soluble MAPK activator exerts antitumor activity in melanoma cells resistant to the BRAF inhibitor vemurafenib. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015;95:16–27. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Federici L, et al. Structural basis for the binding of the anticancer compound 6-(7-nitro-2,1,3-benzoxadiazol-4-ylthio)hexanol to human glutathione s-transferases. Cancer Res. 2009;69:8025–8034. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sau A, et al. Targeting GSTP1-1 induces JNK activation and leads to apoptosis in cisplatin-sensitive and -resistant human osteosarcoma cell lines. Mol. Biosyst. 2012;8:994–1006. doi: 10.1039/C1MB05295K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.De Luca A, et al. A novel orally active water-soluble inhibitor of human glutathione transferase exerts a potent and selective antitumor activity against human melanoma xenografts. Oncotarget. 2015;6:4126–4143. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Luisi G, et al. Nitrobenzoxadiazole-based GSTP1-1 inhibitors containing the full peptidyl moiety of (pseudo)glutathione. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2016;31:924–930. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2015.1070845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.De Luca A, et al. The nitrobenzoxadiazole derivative MC3181 blocks melanoma invasion and metastasis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:15520–15538. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.De Luca A, Hartinger CG, Dyson PJ, Lo Bello M, Casini A. A new target for gold(I) compounds: glutathione-S-transferase inhibition by auranofin. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2013;119:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Fahey RC. Novel thiols of prokaryotes. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001;55:333–356. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lucente G, Luisi G, Pinnen F. Design and synthesis of glutathione analogues. Il Farm. 1998;53:721–735. doi: 10.1016/S0014-827X(98)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mahadevan D, Sutton GR. Ezatiostat hydrochloride for the treatment of myelodysplastic syndromes. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2015;24:725–733. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2015.1021003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bezerra DP, et al. Overview of the therapeutic potential of piplartine (piperlongumine) Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;48:453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ruzza P, Calderan A. Glutathione transferase (GST)-activated prodrugs. Pharmaceutics. 2013;5:220–231. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics5020220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ramsay EE, Dilda PJ. Glutathione S-conjugates as prodrugs to target drug-resistant tumors. Front. Pharmacol. 2014;5:181. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dourado DF, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ, Mannervik B. Mechanism of glutathione transferase P1-1-catalyzed activation of the prodrug canfosfamide (TLK286, TELCYTA) Biochemistry. 2013;52:8069–8078. doi: 10.1021/bi4005705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Tew KD. TLK-286: a novel glutathione S-transferase-activated prodrug. Expert. Opin. Invest. Drugs. 2005;14:1047–1054. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.8.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Vergote I, et al. Randomized phase III study of canfosfamide in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin compared with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin alone in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer. 2010;20:772–780. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181daaf59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kavanagh JJ, et al. Phase 2 study of canfosfamide in combination with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in platinum and paclitaxel refractory or resistant epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2010;3:9. doi: 10.1186/1756-8722-3-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Sequist LV, et al. Phase 1-2a multicenter dose-ranging study of canfosfamide in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel as first-line therapy for patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2009;4:1389–1396. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181b6b84b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Rojas LB, Gomes MB. Metformin: an old but still the best treatment for type 2 diabetes. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2013;5:6. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-5-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Ikhlas S, Ahmad M. Metformin: Insights into its anticancer potential with special reference to AMPK dependent and independent pathways. Life Sci. 2017;185:53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Morales DR, Morris AD. Metformin in cancer treatment and prevention. Annu. Rev. Med. 2015;66:17–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-062613-093128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Whitburn J, Edwards CM, Sooriakumaran P. Metformin and prostate cancer: a new role for an old drug. Curr. Urol. Rep. 2017;18:46. doi: 10.1007/s11934-017-0693-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhou XL, et al. Association between metformin and the risk of gastric cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Oncotarget. 2017;8:55622–55631. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rautio J, Vernerova M, Aufderhaar I, Huttunen KM. Glutathione-S-transferase selective release of metformin from its sulfonamide prodrug. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:5034–5036. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Huttunen KM, et al. The first bioreversible prodrug of metformin with improved lipophilicity and enhanced intestinal absorption. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:4142–4148. doi: 10.1021/jm900274q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Xu W, Liu LZ, Loizidou M, Ahmed M, Charles IG. The role of nitric oxide in cancer. Cell. Res. 2002;12:311–320. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Shami PJ, et al. JS-K, a glutathione/glutathione S-transferase-activated nitric oxide donor of the diazeniumdiolate class with potent antineoplastic activity. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2003;2:409–417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Findlay VJ, et al. Tumor cell responses to a novel glutathione S-transferase-activated nitric oxide-releasing prodrug. Mol. Pharmacol. 2004;65:1070–1079. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.5.1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Chakrapani H, et al. Synthesis, mechanistic studies, and anti-proliferative activity of glutathione/glutathione S-transferase-activated nitric oxide prodrugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008;16:9764–9771. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.09.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Xue R, et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of diazeniumdiolate-based DNA cross-linking agents activatable by glutathione S-transferase. Org. Lett. 2016;18:5196–5199. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Genovese I, Ilari A, Assaraf YG, Fazi F, Colotti G. Not only P-glycoprotein: amplification of the ABCB1-containing chromosome region 7q21 confers multidrug resistance upon cancer cells by coordinated overexpression of an assortment of resistance-related proteins. Drug. Resist. Update. 2017;32:23–46. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2017.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.van Gisbergen MW, et al. Chemical reactivity window determines prodrug efficiency toward glutathione transferase overexpressing cancer cells. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016;13:2010–2025. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.6b00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]