Abstract

The role of soluble messengers in directing cellular behaviours has been recognised for decades. However, many cellular processes including adhesion, migration and stem cell differentiation are also governed by chemical and physical interactions with non-soluble components of the extracellular matrix (ECM). Amongst other effects, a cell’s perception of nano-scale features such as substrate topography and ligand presentation, and its ability to deform the matrix via the generation of cytoskeletal tension play fundamental roles in these cellular processes. As a result, many biomaterials-based tissue engineering and regenerative medicine strategies aim to harness the cell’s perception of substrate stiffness and nano-scale features to direct particular behaviours. However, since cell-ECM interactions vary considerably between two-dimensional (2D) and three-dimensional (3D) models, understanding their influence over normal and pathological cell responses in 3D systems which better mimic the in vivo microenvironment is essential to efficiently translate such insights into medical therapies. This review summarises the key findings in these areas and discusses how insights from 2D biomaterials are being utilised to examine cellular behaviours in more complex 3D hydrogel systems, in which not only matrix stiffness, but also degradability plays an important role, and in which defining the nano-scale ligand presentation presents an additional challenge.

Keywords: ECM (extracellular matrix), cell adhesion, hydrogel, integrin, stem cell

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction to mechanotransduction

As the field of biomaterials has evolved over the past decades, researchers have shifted from developing materials that were merely tolerated by the body to creating those that elicit a specific response. Nowhere is this more prevalent than in the fields of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine, in which researchers often aim to form scaffolds that, in addition to providing 3D structural support for tissue growth, also direct cell response. The means by which cellular behaviours are governed by soluble chemical messengers are well established. Signalling molecules such as growth factors interact with cells to trigger various pathways involved in stem cell differentiation and ECM formation, amongst others. In addition to their interactions with soluble cues, however, cells are also influenced by adhesive interactions with their ECM, applying physical forces to it, sensing its deformation and even remodelling it. Like soluble factors, these interactions similarly affect cell behaviour.

The importance of cell-ECM interactions in relaying mechanical signals has long been recognised, but it was not until the early 1990s, when Ingber and colleagues attached magnetic beads to cells and applied a twisting moment, measuring the resistance of the beads to twisting, that the field truly expanded. It was these pioneering experiments which demonstrated that the cell cytoskeleton behaved like a ‘tensegrity’ structure, an interconnected unit that could resist applied forces as an integrated structure [1]. These insights created tremendous excitement in the new field of cell mechanotransduction, which aimed to elucidate the role of mechanical forces in directing cell behaviour. The field of mechanotransduction concerns interconnected phenomena by which cells both respond to applied forces and exert forces on their surrounding ECM. Such physical forces result in changes in cell morphology and cytoskeletal structure, which fundamentally influence cell response.

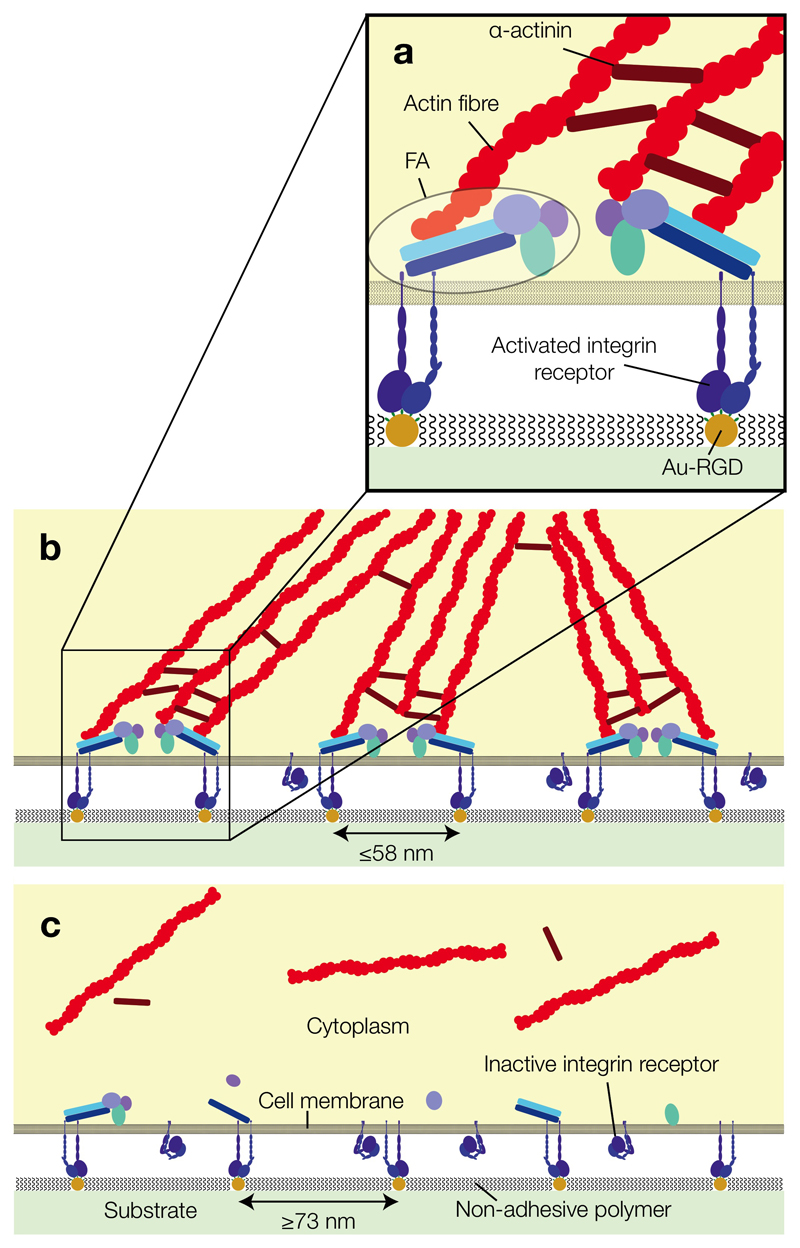

The response of cells to applied and intracellularly generated forces in their interactions with the ECM, however, is only one aspect of how the ECM influences cell behaviour [2]. Amongst other effects, cells similarly respond via mechanotransductive effects caused by changes in nano-scale surface topography and ligand presentation. In 2004, seminal work by Spatz and colleagues [3] utilised non-adhesive polymeric substrates functionalised with precisely spaced adhesion peptides to reveal that cells are highly sensitive to inter-ligand spacing. Substrates patterned with ligands spaced up to 58 nm apart fostered cell attachment and spreading, whereas a distance of 73 nm or more was too great to support efficient adhesion. These and other nano-scale surface features appear to play important roles in directing stem cell differentiation and a myriad of other effects. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) have been shown, for example, to respond by triggering osteogenic differentiation when exposed to nano-scale pits that are slightly disordered as opposed to arranged in aligned, square patterns [4]. It is because of the complex interplay between these interrelated mechanotransductive effects that targeting the nano-scale features of the ECM remains an important means by which to direct cell fate.

Despite these important insights into the role of the ECM in directing cell behaviour, most knowledge in this field has been gained by studying cells cultured on 2D substrates. Whilst 2D systems have provided invaluable insights into cellular mechanisms, the unnatural morphology and polarity of cells residing as a monolayer, as well as the high stiffness of many cell culture substrates, artificially influences these behaviours, resulting in altered matrix synthesis and unphysiological cell migration and differentiation. For example, fibroblasts are spindle-shaped when cultured in 3D collagen gels, with long extensions attached to matrix, whereas on 2D collagen-coated surfaces they instead form numerous stress fibres [5].

Since 2D cell culture inherently misrepresents the in vivo behaviour of most cell types [6–8], there has recently been a shift towards 3D tissue culture systems. These include hydrogels based on biopolymers such as collagen, hyaluronic acid and alginate [5,9]. However, as biologically derived systems are poorly defined in terms of their nano-scale architecture and are subject to batch-to-batch variability, a wide range of synthetic polymers have also been developed, including poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG), poly(caprolactone), poly(vinyl alcohol) and poly(glycolic acid), among others [9,10]. These systems, in which researchers are beginning to assess the effects of mechanotransduction and nano-scale ligand presentation in 3D, are likely to be of great benefit to the fields of tissue engineering, regenerative medicine and stem cell biology [11]. This review discusses these interrelated topics and addresses mechanotransduction and cell response in 2D. We also examine how the 2D cell response often lacks translatability to more in vivo-like 3D situations and discuss synthetic hydrogels, whose characteristics including stiffness, degradability and ligand presentation, can be tuned to influence mechanotransduction in 3D. We end by discussing how the field might best progress to harness our understanding of mechanotransduction to direct cell behaviour for therapeutic purposes.

1.2. Integrin-mediated cell-ECM interactions in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine

The emerging fields of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine seek to “apply the principles of engineering and life sciences toward the development of biological substitutes that restore, maintain, or improve tissue function" [12], often utilising biomaterial scaffolds [13] to achieve these aims. Stem cells are widely used in these fields because of their ability to self renew and differentiate into tissue-specific lineages [14,15]. This requires understanding fundamental cellular behaviours, particularly the interplay between cells and their ECM. Since many biomaterials aim to simulate the ECM in order to direct cell differentiation and localised tissue formation, a more in-depth understanding of how the ECM directs cell behaviour is of critical importance.

Differentiation of stem cells in cell culture systems has typically been achieved using soluble chemical differentiation factors (e.g. dexamethasone for osteogenesis, insulin for adipogenesis and hydrocortisone for smooth muscle cell differentiation). However, ECM characteristics may also be harnessed to direct cell behaviour, in combination with [16], or often without the need for soluble factors [4,17,18]. Where ECM properties have been shown to induce terminal differentiation (as opposed to merely affecting transcript expression), mechanotransduction-mediated effects such as cell shape and cytoskeletal tension appear to be critical [19,20]. Approaches towards harnessing extracellular cues to precisely control stem cell fate therefore first require an understanding of and then an ability to exploit the cell’s interactions with its ECM.

The ECM is a complex network of molecules that fulfils multiple roles within each tissue, the composition and resulting mechanical and biochemical properties of which vary considerably between different tissue types. In addition to providing structural support, strength and elasticity, it guides various cellular processes that influence metabolic activity, proliferation and differentiation, among others. The ECM accomplishes these functions by acting as a substrate for cellular adhesion, polarisation and migration. Additionally, cells are able to remodel the ECM via enzymatic degradation [21] and by applying traction forces to it [22–24]. Some of the major components of the ECM are summarised in Table 1 [5,25,26].

Table 1. Some major ECM components and their functions.

| Component | Functions | Tissue types |

|---|---|---|

| Proteins | ||

| Fibrillar collagens e.g. types I, II, III, V & XI |

ECM architecture, mechanical properties (load bearing, tensile strength and torsional stiffness, particularly in calcified tissues), wound healing and entrapment and binding of extracellular growth factors and cytokines | Bone, cartilage, dentine, muscle, skin, tendon, ligament, blood vessel, invertebral disc, notochord, cornea, vitreous humour and other internal organs (e.g. lung, liver, spleen) |

| Fibril-associated collagens e.g. types IX & XII |

Linked to fibrillar collagens, may regulate organisation, stability and lateral growth of fibrillar collagens | Cartilage, tendon, ligament and other tissues |

| Network-forming collagens e.g. types IV, VII, VIII, X & XIII |

Molecular filtration | Basal lamina & basement membranes beneath stratified squamous epithelial tissues (e.g. cornea), growth plate cartilage |

| Elastin | Tissue elasticity, load bearing and storage of mechanical energy | Artery, lung, elastic ligament, skin, bladder and elastic cartilage |

| Glycoproteins | ||

| Laminins | Meshed network that influences cell adhesion, phenotype, survival, migration and differentiation | Basal lamina |

| Fibronectin | Binds to collagen, fibrin and glycosaminoglycans, influencing gastrulation, cell adhesion, growth, migration, wound healing and differentiation | Widely distributed (deposited by fibroblasts) |

| Fibrillins | Scaffolds for elastin deposition | See elastin; also: brain, gonads, ovaries |

| Glycosaminoglycans | ||

| Hyaluronic acid | Lends tissue turgor and facilitates cell migration during tissue morphogenesis and repair | Widely distributed |

| Proteoglycans e.g. heparan, chondroitin & keratin sulfates |

Negatively charged proteoglycans that attract water, providing a reservoir for growth factors and other signalling molecules | Bone, cartilage, skin, tendon, ligament, cornea |

Mammalian cells attach to the ECM via integrins, heterodimeric transmembrane proteins consisting of α and β subunits. In humans, 18 α and 8 β subunits exist in 24 possible conformations [27]. On the extracellular side, integrins recognise specific amino acid sequences, allowing them to adhere to various components of the ECM. Intracellularly, integrins attach to the cell’s cytoskeleton via a series of linker proteins. As a result, integrins mediate cell-ECM adhesion through a complex feedback mechanism, acting both as mechanosensors and bi-directional signalling receptors, which pass environmental information across the cell membrane and intracellular information to the ECM. Because the direct mechanical link between the ECM and the cell cytoskeleton is mediated by integrins, mechanical signals are carried directly to the nucleus. As a result, this mechanism is more efficient and faster than other signalling methods, taking ~2 μs to propagate 50 μm, compared to ~25 s for small signalling molecules and ~50 s for motor proteins [28,29].

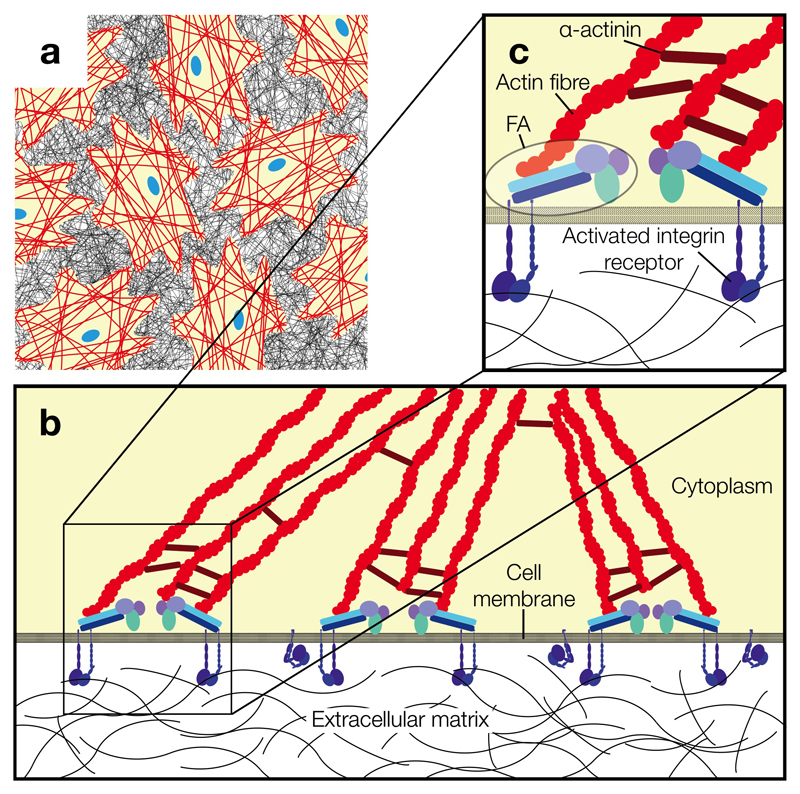

Cell-ECM interactions are initiated by the binding of integrin receptors to ECM ligands (Fig. 1). This is induced by allosteric conformational changes on either the extracellular or intracellular end [30], followed by formation of protein aggregates called focal adhesions (FA) on standard 2D surfaces. FA link integrin clusters to actin filaments, acting as cytoskeletal anchor points that transduce intracellular forces across the membrane to the ECM. This results in activation of the ERK/MAPK (extracellular signal-related-kinase / mitogen-activated protein kinase) [31] and RhoA/ROCK (Rho-associated protein kinase) pathways [32]. During clustering, actin polymerisation occurs, radiating outward from the clusters. Myosin II molecules between actin clusters contract and the force generated stimulates Src kinase-dependent lamellipodial extension and lateral separation of clusters. This enables cell spreading and is followed by subsequent retraction of myosin II, causing inward movement of clusters and increasing cytoskeletal tension [33]. It is across these stiff fibres that mechanical forces are transduced throughout the cell and across the membrane. Lateral integrin mobility and clustering is therefore required for efficient cell spreading and motility of anchorage-dependent cells on 2D surfaces [34–37], and is a primary means by which cells interact with the extracellular environment.

Fig. 1.

Integrin-mediated cell-ECM adhesion. (a) Cells (yellow) residing on their ECM (black mesh). Red lines represent actin stress fibres and nuclei are shown in blue. (b) Integrin-mediated cell adhesion to the ECM requires clustering of multiple integrin receptors and FA complexes for efficient actin fibre assembly. (c) A detailed view of FA complexes connecting ECM-bound integrin receptors to the actin cytoskeleton. FA consist of proteins including, but not limited to vinculin, talin, paxillin and focal adhesion kinase.

In cells fully embedded within a 3D collagen matrix, however, focal adhesion proteins such as vinculin, paxillin and talin, amongst others, do not form aggregates but are dispersed diffusely throughout the cytoplasm. Despite the lack of distinct FA, these proteins are still indirectly implicated in modulating cell traction and speed of motility, by affecting cell membrane protrusion and matrix deformation via mechanotransductive processes [38].

The most notable integrins involved in cell-ECM adhesion bind to ligands within fibronectin (α4β1, α5β1, α5β3 and αVβ3), collagen (α1β1, α2β1, α10β1 and α11β1) and laminin (α3β1, α6β1 and α7β1). RGD is the most prevalent peptide motif, present in fibronectin, laminin, vitronectin, fibrinogen, osteopontin, bone sialoprotein and various other extracellular proteins. It has high affinity for a wide range of receptors, including eight human integrin heterodimers, most notably αVβ3 and α5β1 [39–41]. Other common adhesive peptide motifs include triple helical GFOGER (fibrillar collagen Types I, II and III), IKVAV (laminin α1 chain), YIGSR (laminin β1 chain), REDV (fibronectin) and DGEA (Type I collagen) [5]. In some cases, motifs are concealed within the peptide and are only exposed through conformational changes, induced by surface adsorption, interaction with other proteins, mechanical distortion or proteolysis [42]. When integrins bind to ECM components, conformational changes in the protein occur, triggering intracellular protein aggregation and cell signalling cascades [21]. Understanding such integrin-mediated cell-ECM interactions is fundamental to elucidating how biomaterials may be harnessed to regulate cell behaviour. Indeed, by integrating peptide motifs into artificial matrices with precise spatial distribution, researchers may be able to specifically direct stem cell differentiation.

2. The effects of 2D substrate properties on cell behaviour

2.1. Influence of nano-scale topography on cell morphology and differentiation

The native ECM possesses tissue-specific micro- and nano-topography. For example, a triple helical Type I collagen molecule is typically 300 nm long and 1.5 nm in diameter. In bone, a collagen fibril has a diameter of 80–100 nm (compared to 260–410 nm in tendon), with D-spacing (overlapping 5–10 nm deep striations) occurring every 67–68 nm. Apatite crystals measuring approximately 50 x 25 x 4 nm are embedded in collagen bundles in bone and are organised in various orientations within the matrix, depending upon location, with fibres running radially, in parallel or in woven conformations [43,44]. Such features only comprise a fraction of the complexity of native bone ECM architecture, which also contains non-collagenous proteins, proteoglycans and glycoproteins [5]. These specific nano-topographical features of bone ECM influence various cellular activities. For example, rough hydroxyapatite, calcite and titanium surfaces with nano-scale textures (formed by different spraying, sawing or polishing techniques) have been shown to enhance both osteoblast adhesion and differentiation [45] and osteoclastic resorption [46,47] in comparison to smooth substrates. Here we briefly summarise some of the key findings regarding the effects of nano-topographical features on the behaviours of various cells, and how these may be used to direct stem cell differentiation independently from biochemical cues. For more comprehensive reviews refer to refs. [15] and [48]. Due to the focus of this review on nano-scale features, micro-scale effects are not discussed.

The most widely studied effect of topography on cellular behaviour is the well-established phenomenon of contact guidance, in which cells align and polarise in accordance with anisotropic surface features. This is best exemplified in polarised cell types, such as neural cells and their progenitors, neural stem cells (NSC). For example, neural cells show cell type-specific alignment when cultured on ridged surfaces known as nano-gratings. Xenopus spinal neurons sprout neurites in parallel and hippocampal axons align perpendicular to ridges [49]. Similarly, nano-gratings with ridges up to 350 nm wide and 500 nm high trigger embryonic stem cell (ESC) [50] and NSC [51] alignment, elongation, actin rearrangement and differentiation down specific neuronal lineages, in the absence of growth factors or cytokines [51]. Nano-gratings have also been shown to affect the morphology, cytokine production and migration of epithelial cells [52–54] and induce contact guidance in fibroblasts, endothelial and smooth muscle cells [55], even inducing transdifferentiation of mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) down neuronal lineages [56]. 2D substrates may therefore be patterned with nano-scale topographies in order to specifically direct stem cell fate.

The effects of nano-topography on MSC and their derivatives have also been widely studied. Dalby and colleagues, for example, have shown that substrates with raised islands of nano-scale height influence morphology and spreading of fibroblasts and osteoblastic differentiation of MSC, compared to flat substrates [57–59]. They also demonstrated that nano-pits (100 nm depth, 120 nm diameter, 300 nm spacing) arranged in slightly disordered grids (with up to 50 nm random offset in both planes) cause an increase in fibrillar adhesion length, mineral production and osteoblastic differentiation of osteoprogenitor cells and MSC, compared to ordered grids and randomly disordered patterns [4,60]. These in vitro findings suggest that topographical cues on materials can direct cell behaviour at the cell-material interface. For example, ridged substrates may be used for expansion and differentiation of explanted stem cells down a specific lineage, such as for tailored treatment of cardiovascular, skeletal or neurodegenerative diseases. Nevertheless, despite a wealth of evidence suggesting that nano-topography directs cellular behaviours, comprehensive reviews have failed to identify clear trends, likely because of differences between research groups in creating the materials [55]. By contrast, studies in which the geometry of adhesive patterns, the nano-scale presentation of ligands and the stiffness of substrates have been investigated have given a clearer insight into the precise mechanisms by which ECM interactions govern cellular behaviours and are discussed below.

2.2. Cell response to changes in cytoskeletal tension

Although a number of potential mechanisms have been put forward to explain how nano-topography regulates cell behaviour, one with particularly strong evidence is that changes in cell morphology and cytoskeletal structure and tension regulate cellular response. Studies on the cytoskeletal response of individual cells seeded on adhesive areas of varying geometry have provided an interesting insight into this phenomenon. These studies utilise adhesive patches of controlled shapes and areas on non-adhesive backgrounds. In 2004 McBeath et al. demonstrated that cell shape regulates MSC differentiation by modulating endogenous RhoA activity. Cells cultured on small (1,024 μm2) islands of fibronectin assumed a round morphology and expressed dominant-negative RhoA, causing them to commit to an adipogenic lineage. By contrast, when seeded on large (10,000 μm2) patches, MSC were able to flatten, triggering osteoblastic differentiation mediated by RhoA in its active form. In both cases, RhoA-mediated differentiation was dependant on the respective morphologies of the cells. By contrast, activation of the RhoA effector, ROCK, resulted in osteogenesis, regardless of morphology and was dependent on cytoskeletal tension [20].

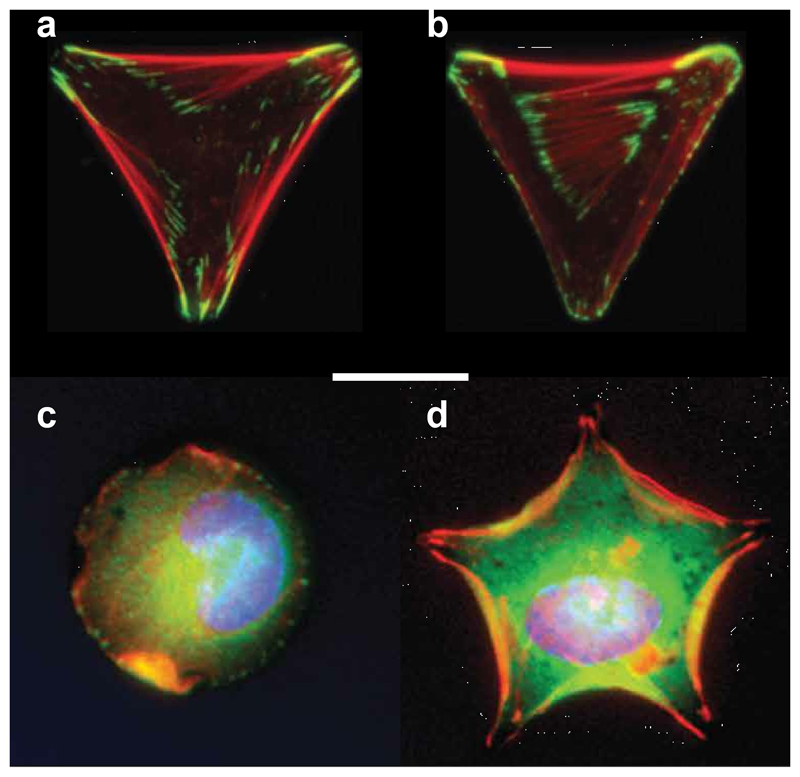

Following the same principle, cell behaviour may also be controlled by dictating cell shape whilst maintaining a constant cell spread area. Staining of individual epithelial cells cultured on substrates patterned with fibronectin in T, Y, V, Δ and Π shapes revealed high concentrations of actin stress fibres and vinculin at non-adhesive edges (Fig. 2a–b). This positively correlated with FA and actin cable size. Differentiation of single MSC cultured on adhesive patterns of the same area but different geometry also varied, depending on the shape of the RGD patterned area. Adipogenic differentiation was favoured by cells cultured on round islands, whilst shapes with steeper angles promoted osteogenic differentiation, with the strongest effect being observed on stellar islands (Fig. 2c–d) [61]. These results provide insight into the interplay between cytoskeleton conformation and differentiation, highlighting how cells may be directed down specific lineages by altering these factors.

Fig. 2.

Fluorescent micrographs of cells residing on different adhesive geometries (scale bar, 10 μm). Individual epithelial cells seeded on: (a) Y-shaped and (b) V-shaped adhesive fibronectin patterns on a non-adhesive background. Actin filaments (red) are wider and more numerous along non-adhesive edges, where they resist greater cytoskeletal tension. Vinculin (green) is concentrated at FA. Adapted with permission from ref. [62], © John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Individual MSC cultured on: (c) round and (d) stellar adhesive geometries of the same surface area, with stronger actin staining (red) and osteogenic differentiation associated with steeper angles. Adapted with permission from ref. [61], © Elsevier Ltd.

2.3. The role of ligand presentation in cell attachment and response

Another factor that appears to be of critical importance in nano-scale feature control of cell behaviour is ligand presentation. Although early studies reported conflicting results regarding the minimum concentration and spacing of adhesive ligands required to induce efficient cell spreading, [63–65] technological refinements over the past decade have enabled researchers to precisely control ligand patterning on 2D substrates [34,36]. Block or diblock copolymer micelle nano-lithography (BCML) in particular has enabled nano-patterning of ligands such as RGD on soft substrates [66]. BCML involves first patterning glass slides with regularly spaced Au nanodots, to which linker molecules are attached. The nanodots are then transferred to a non-adhesive copolymer, binding via the linkers and providing hydrophilic regions that are then functionalised with RGD. Polymer molecular mass and water content may be varied to regulate ligand spacing [66]. The matching of nanodot (6–8 nm) and integrin (8–12 nm) diameters [3,67,68], the steric hindrance of RGD [69] and the minimal flexibility of the short linker molecule (~1 nm amplitude) [3] result in formation of a single FA per nanodot.

Spatz and colleagues showed that various anchorage-dependent cells, including osteoblasts, fibroblasts and melanocytes adhered and spread efficiently on BCML substrates with an inter-ligand distance of 28 or 58 nm, whereas ligands spaced 73 or 85 nm apart caused ruffling of the cell membrane and significantly altered cell polarity and morphology (Fig. 3). Although cells were able to bind, FA were not established and adhesion was therefore unstable. This demonstrated that the critical, maximal inter-ligand spacing that supports these behaviours lies between 58 and 73 nm [3,70]. Moreover, on BCML substrates patterned with a gradient of ligand spacing, osteoblasts have been shown to migrate to the region with ligands spaced ~60–70 nm apart and polarise in parallel with the direction of the gradient [71]. Ligand spacing, however, does not only affect adhesion; on polymeric substrates formed by a self-assembly technique, MSC have been shown to be sensitive to inter-ligand spacing, with osteogenic differentiation influenced by small distances and adipogenic differentiation triggered by large distances [72]. Similarly, anchorage-independent cells show sensitivity to ligand spacing. A maximal inter-ligand distance of 32 nm was found to be critical for glycolipoprotein clustering in haemopoietic stem cells, with 20 nm spacing causing a more prominent effect [41], and cell signalling between T cells or between natural killer cells across synapses was upregulated at 25 and 34 nm spacing compared to 69 or 104 nm [73].

Fig. 3.

The effect of ligand spacing on FA clustering and actin cytoskeleton assembly in anchorage-dependent cells, shown to approximate scale. (a) A detailed view of integrin receptors bound to an Au-RGD-functionalised BCML substrate. Adhesion triggers recruitment of intracellular proteins, which aggregate to form FA. Lateral clustering of FA is followed by formation of actin fibres. (b) Substrates patterned with ligands spaced up to 58 nm apart enable FA formation and clustering, whereas (c) substrates with ligands spaced 73 nm or further apart do not support efficient FA formation, cell adhesion and spreading.

However, ligand spacing is not the only factor that invokes cellular responses – in fact, it is the clustering of ligands within a localised area that likely supports FA formation. Maheshwari et al. demonstrated that clustering of multiple ligands within a localised region enhances cell adhesion and motility compared to evenly dispersed ligands [34]. As ligand spacing is proportional to ligand density in regularly spaced grids, so-called ‘micro-nano-patterns’ have been investigated to separate these effects. BCML substrates with microdomains of regularly spaced Au-RGD (~58 nm) arranged in 2 x 2 μm squares, 1.5 μm apart [3] or in 1.5 μm diameter spots, 1.7 μm apart [74] were compared to extensive areas with ~58 nm spacing. Despite having lower overall ligand density than extensive areas, micro-nano-patterned substrates supported FA assembly. These observations demonstrated that localised ligand clustering rather than overall ligand density was the determining factor in regulating FA assembly. The importance of clustering was further reinforced by a study utilising nanoimprint lithography, which revealed that adhesion was significantly improved when ligands were arranged in clusters of four or more (with ligands spaced ≤60 nm), compared to clusters containing two or three ligands each, independent of global density [75].

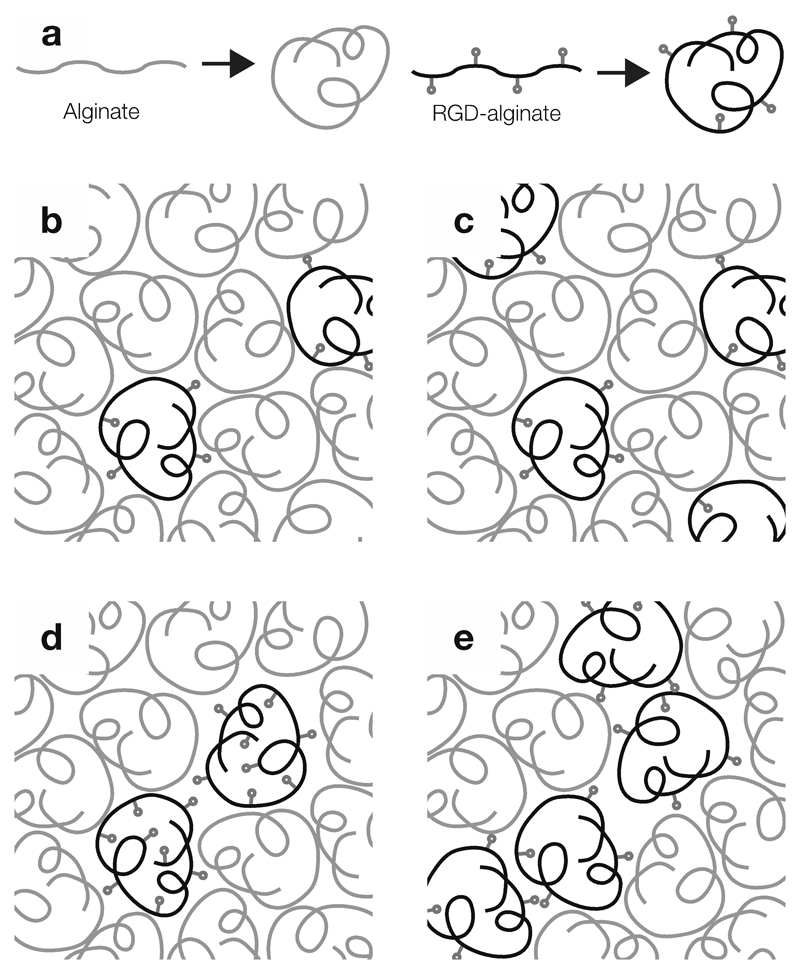

Linderman, Mooney and colleagues have also been instrumental in developing models that predict and assess effects of ligand presentation on FA formation on RGD-functionalised 2D alginate substrates. They first demonstrated that an inter-ligand spacing of 36 nm supported higher preosteoblast proliferation and osteogenic differentiation than 76 nm, independent of overall ligand density [76]. They subsequently revealed that ligand-rich gels supported adhesion and spreading, whereas gels with low RGD content influenced osteogenic differentiation [77–79]. Although this latter observation appears to contradict findings by Lee et al. [76] and others [72], who associated osteogenesis with smaller distances, the differences are likely due to variations in the presentation of ligands to cells caused by steric hindrance [78]. Micro-nano-patterned gels with identical ligand density but alterations in cluster size (Fig. 4) [80] indicated correlation between cell spreading and the number of bound integrins; small clusters of integrin were linked with focal adhesion kinase phosphorylation, whereas large clusters were associated with osteogenic differentiation.

Fig. 4.

Schematic showing alginate hydrogels with varying ligand spacing and clustering. (a) RGD-functionalised alginate chains coil to form island amongst blank alginate coils. (b–c) Overall ligand density can be varied by altering island concentration, in turn varying ligand spacing. (d–e) Micro-nano-patterning of hydrogels using islands with different ligand numbers allows variation in ligand clustering while maintaining constant overall density.

Based on these findings, it has been proposed that cells interpret and explore their local environments by responding to differentially positioned ligand clusters, with high spatial sensitivity (~1 nm) and optimal ligand spacing of ≥60 and ≤70 nm [71]. This coincides with the predicted 68 nm occurrence of peptide GFOGER in the D-spacing of Type I collagen fibrils [5,43]. The mechanisms by which cells sense these environmental cues and respond through cytoskeletal reorganisation have been reviewed by Geiger et al. (2009) [81] and may be implicated in tissue repair and cancer metastasis [82,83].

2.4. The effect of 2D substrate stiffness on cell shape, traction and stem cell differentiation

Stiffness describes the rigidity of a material, or how much it resists deformation in response to an applied force. Elastic or Young’s modulus is an engineering term, reported in units of Pascals (Pa), that describes the size-independent inherent stiffness of a material. The elastic moduli of mammalian tissues can vary by over 7 orders of magnitude, and are reported to be as low as 167 Pa for breast tissue [84] and as high as 5.4 GPa for cortical bone [85]. By contrast, moduli of traditional 2D tissue culture substrates range from ~3 GPa for polystyrene to 69 GPa for soda-lime glass, much higher than most tissue types [86]. Cells apply tractions forces to their underlying substrate, essentially ‘feeling’ this stiffness. In 1997, Pelham & Wang demonstrated that cells behaved differently when cultured on relatively soft or stiff substrates formed from polyacrylamide hydrogels [87]. In general, cells generate greater traction forces, establish more stable FA, form more defined actin stress fibres and spread more extensively on rigid surfaces compared to compliant. They also migrate more quickly on soft surfaces and adhere more tightly to rigid surfaces. Here we outline some of the key effects of 2D substrate stiffness on cellular behaviours. For more comprehensive reviews, several commentaries by Discher and colleagues [88–90] and more recently by Evans & Gentleman (2014) [91] are recommended. The effects of 3D matrix stiffness are discussed separately in the following section.

Importantly for tissue engineering and regenerative medicine applications, substrate stiffness has recently been show to regulate stem cell differentiation. Compliant hydrogel matrices formed from polyacrylamide with a modulus comparable to brain tissue cause MSC to differentiate down neuronal lineages; stiffer matrices that mimic muscle induce myogenic differentiation; and matrices with high rigidity similar to collagenous bone promote osteogenesis [92]. ESC differentiation has similarly been shown to be regulated by substrate stiffness. Evans et al. (2009) demonstrated that when cultured on poly(dimethylsiloxane) (PDMS) substrates, cell spreading, growth, osteogenic differentiation and expression of several genes involved in early mesendoderm differentiation were upregulated on stiff substrates compared to compliant (Fig. 5) [93]. Muscle cell differentiation has also been shown to be optimal on substrates with a narrow range of moduli, similar to those of the healthy native tissue [89,94]. Moreover, when cultured on stiff, fibronectin-functionalised polyacrylamide, MSC stretch the fibronectin fibres, gauging the stiffness of the underlying substrate and up-regulating osteogenic differentiation [95]. Although a direct stiffness-sensing mechanism [96] has recently been called into question [91,97], the importance of this is that biomaterials and perhaps tissue engineering scaffolds have the potential to be designed with particular matrix stiffnesses tuned to direct differentiation of stem cells down specific lineages.

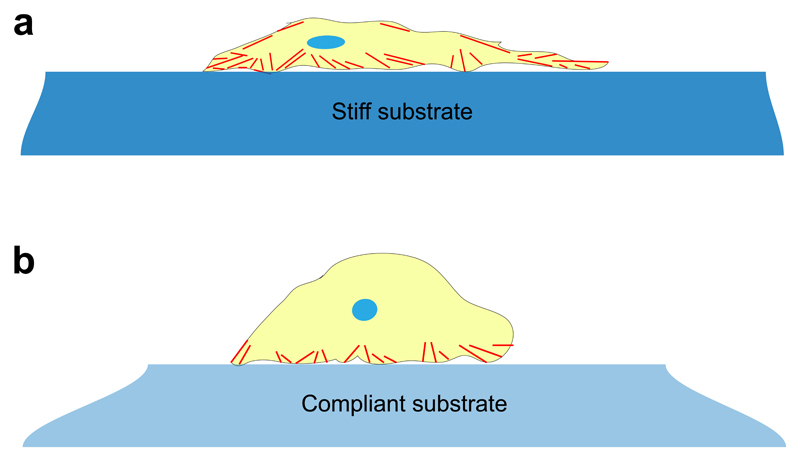

Fig. 5.

Substrate stiffness influences cell morphology and differentiation. (a) Adherent cells (yellow) are unable to generate sufficient traction force to deform stiff hydrogel substrates (dark blue). As a result, they develop spread morphologies with many well-defined actin fibres (red). (b) By contrast, cells cultured on compliant substrates (pale blue) deform the matrix, and assume a more rounded morphology with fewer and less defined stress fibres. The distorted shapes of the hydrogel substrates of varying stiffness represent the deformation induced by the cell.

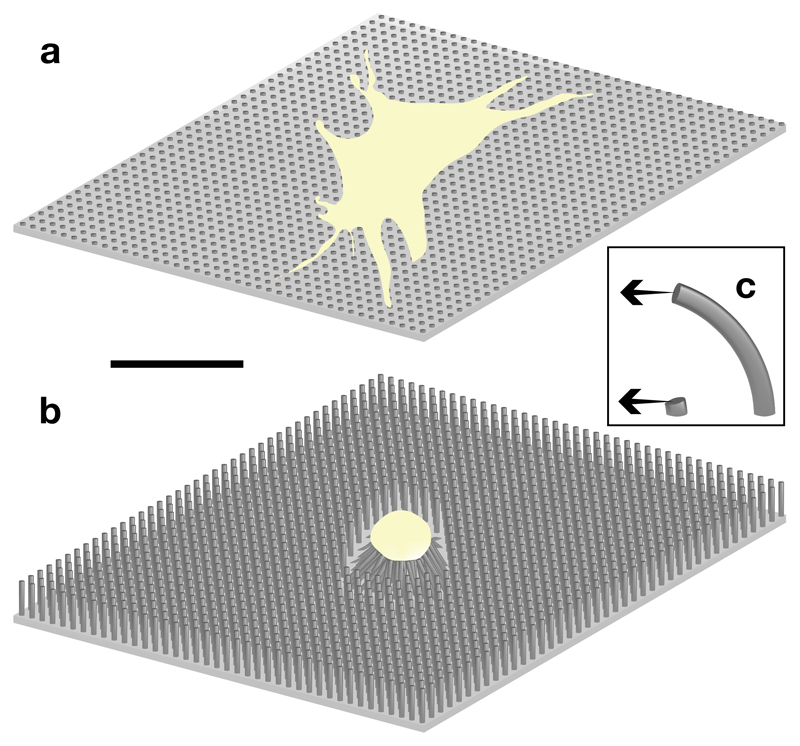

Although with fewer direct applications in tissue engineering, in addition to modifiable hydrogels, another approach whereby the effects of substrate stiffness may be visualised involves patterning arrays of elastomeric microposts with varying heights. Taller, flexible posts simulate a more compliant substrate, whilst shorter posts bend less readily and appear stiff to cells. Studies utilising micropost arrays demonstrate that cells perceive the flexibility of microposts as they do the stiffness of hydrogels: MSC cultured on long posts assume a rounded morphology and those grown on short, rigid posts spread more efficiently. When cultured in osteogenic and adipogenic co-induction medium, osteogenesis is favoured on short and adipogenesis on long posts, respectively (Fig. 6) [98]. Recently Fu and colleagues reported that micropost rigidity may be harnessed to regulate differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells down a motor neuron lineage, with soft substrates giving rise to a ten-fold increase in cell number and four-fold increase in purity of differentiated motor neuron cells compared to rigid or flat substrates [99].

Fig. 6.

Microposts of varying height and stiffness induce different MSC morphologies. Micropost diameter 2 μm, spacing 4 μm, drawn to scale (scale bar 50 μm). (a) Short (0.97 μm), rigid microposts induce spread morphology and osteoblastic differentiation, whereas (b) MSC cultured on long (12.9 μm), flexible microposts favour adipogenic differentiation. (c) Schematic showing differences in flexibility of microposts subjected to equal forces, as a function of height.

Such effects are likely not an artefact of 2D in vitro culture systems, as tissue stiffness appears to affect similar cellular behaviours in in vivo situations as well. During morphogenesis, variations in localised ECM turnover may result in regions of varying stiffness which then affect cell differentiation. For example, it has been proposed that compliant areas under epithelial tension induce bud formation, implicating these processes in embryogenesis and tissue healing [31]. Similarly, during development, beating cardiomyocytes and collagen-depositing fibroblasts appear to work synergistically via a complex mechanotransductive feedback mechanism [100]. Tissue stiffness may also be associated with oncogenic transformation. Whilst apoptosis is higher in non-transformed cells cultured on compliant substrates, transformed cells maintain similar apoptotic levels on substrates of different moduli [82]. Reviews by Jaalouk & Lammerding (2009) and Wozniak & Chen (2009) take a more in-depth look at the implications of mechanotransduction in gastrulation and disease states [101,102].

3. Evolving insights into the cell niche

3.1. The transition from 2D models to 3D hydrogel systems

Although many of the material systems explored so far have yielded fascinating insights into how ECM properties affect cell response, the majority of these findings have been reported in 2D. As cells adopt unnatural morphologies and cytoskeletal arrangements in 2D and since most cell types reside in 3D in their native tissue, there is an urgent need for materials that provide a 3D environment for cells that can more accurately simulate the mechanical and biochemical properties of the ECM, to enable us to better understand true cell behaviour. Researching in this third dimension, however, adds complexity to experimental systems, since in addition to stiffness, topography and ligand presentation, other factors such as the porosity and degradability of a material may also affect cell behaviour. For example, cells’ movements are relatively unrestricted when they are cultured on 2D surfaces. However, in many tissues and 3D cultures, cells must enzymatically degrade their surroundings to migrate. Materials utilised to study cell-ECM interactions in 3D and direct cellular behaviours should therefore allow for precise control over not only factors such as ligand presentation and matrix stiffness, but also degradability.

Hydrogels, which are water swollen, biocompatible polymer networks, are the most common systems utilised to examine cell behaviour in 3D. Many hydrogels can be formed under mild conditions, allowing for encapsulation of live cells. Their characteristics, such as stiffness, degradability and ligand presentation can also be controlled by altering their composition and synthesis or by employing various polymer chemistry techniques. Although still a very new field, advanced hydrogel systems are beginning to emerge with the capabilities to explore the effects of factors such as ligand presentation, stiffness and degradability on cell behaviours in 3D.

Here we explore discuss early findings reported in hydrogel systems. We also explore the advantages of utilising hydrogels formed using specific chemistries and how these systems can best be employed to isolate the contributions of various factors in directing stem cell fate and ultimately tissue formation.

3.2. The effects of 3D matrix stiffness and degradability on cell behaviour

As 2D substrates with varying stiffness have been found to regulate stem cell fate, many have hypothesised that 3D environments which mimic the stiffness of native tissue would similarly promote stem cell differentiation down particular lineages. In 2010, Mooney and colleagues investigated the effect of substrate stiffness on cells encapsulated within 3D RGD-presenting alginate hydrogels. These studies were performed in non-enzymatically degradable gels, in order to keep stiffness constant throughout experimentation, and RGD density was varied in parallel with changes in stiffness. They found that although MSC differentiate in response to 3D matrix stiffness, the mechanism differs from that observed in cells cultured on 2D substrates [23]. That is, rather than being correlated with cell morphology, matrix stiffness directed stem cell fate by modulating integrin binding through reorganisation of ligand presentation on the nano-scale. Matrices of 11–30 kPa induced osteogenic differentiation of MSC in 3D in a process that was dependent on cell traction. Adipogenesis was observed in gels with moduli of 2.5–5 kPa, consistent with previous studies on substrate stiffness in 2D. Mooney and colleagues employed Förster resonance energy transfer, a fluorescence imaging technique, to confirm that cells reorganised their matrix via a traction-mediated mechanism and it was this activity that controlled stem cell fate. Consistent with previous studies where cells were cultured on 2D substrates of different stiffnesses [22,103], they also demonstrated that cells residing in compliant 3D matrices are unable to develop mature FA in order to exert traction forces, whereas cells cultured in rigid matrices are unable to generate sufficient force to deform the matrix, again highlighting the role of cell-mediated traction forces in regulating cell stem cell fate. More recent work by Mooney and colleagues, in which fibroblasts were cultured in 3D interpenetrating networks consisting of Type I collagen and alginate, further highlights the effect of matrix stiffness on cell morphology and signalling, independently from gel architecture and ligand concentration. Stiffer matrices induced upregulation of inflammatory mediators, indicating that stiffness may induce fibroblast recruitment and matrix deposition in wound healing [104].

The importance of substrate stiffness in 3D systems in directing MSC differentiation, however, may not hold for all systems. In 2013, Burdick and colleagues highlighted the importance of degradation-mediated cell traction forces in directing cell fate [24]. Instead of culturing MSC in ionically cross-linked, non-degradable hydrogels (such as alginate), they examined cell differentiation in covalently cross-linked degradable gels based on methacrylated hyaluronic acid. Their results surprisingly show that the degradability of the hydrogel materials directed stem cell fate, rather than their stiffness. MMP-degradable, chemically cross-linked gels allowed for a high degree of degradation and cell spreading, thus enabling cells to generate traction forces. As has been reported in 2D systems, the generation of traction forces similarly promoted osteogenesis [20]. By contrast, gels formed by photo radical cross-linking prevented degradation and cell spreading and inhibited the MSC’s ability to generate traction forces, promoted adipogenic differentiation. Similarly, when the degradable material was later subjected to secondary cross-linking by exposure to UV light, further degradation of the matrix was reduced and a switch from osteogenesis to adipogenesis was induced.

In addition to differentiation, other cellular processes also appear to be controlled by matrix stiffness in 3D. For example, migration of preosteoblasts cultured in 3D MMP-degradable PEG gels was highly dependent on matrix stiffness as a function of cross-linking density. In gels with low cross-linking density, migration was predominantly non-proteolytic, depending only on non-destructive movement through the porous matrix. By contrast, cell invasion in more densely cross-linked hydrogels was reliant on greater proteolytic degradation of the matrix [105]. Moreover, recent findings also indicate that cells may even retain mechanical cues from past physical environments and continue to respond to them when the mechanical properties of the matrix are altered. Yang et al. cultured MSC first on stiff tissue culture polystyrene (~3 GPa) and then on soft PEG hydrogel substrates. Preconditioning on the unphysiologically rigid polystyrene was shown to bias MSC towards osteogenic differentiation and depended on the time of exposure to the stiffer 2D substrate. They also encapsulated MSC in 3D PEG hydrogels (~10 kPa) formed by reversible photo-polymerisation, which allowed matrix stiffness to be later tuned to ~2 kPa. Their response was similar to in 2D and was reversible or irreversible, depending on exposure time to the stiffer matrix [106].

Taken together, these findings highlight the importance of matrix degradability and traction forces in 3D systems, but provide little consensus on the role of matrix stiffness in directing stem cell differentiation. This lack of consensus likely arises due to discrepancies between the materials used to assess cell behaviour. The work by Mooney and colleagues in 2010 utilised non-degradable hydrogels in order to independently examine the effect of stiffness [23]. In their more recent publication, the authors note that, due to the degradable nature of the material, the study was limited to 48 hours [104]. In both cases therefore, the effect of matrix degradability, which appears to be of great importance [24], was not considered. Since matrix stiffness will vary as a cell remodels its microenvironment via enzymatic degradation and exertion of traction forces, understanding the effects of stiffness and degradability in 3D, both independently and in combination, is of key importance for the progression of the field.

3.3. Incorporation and patterning of biochemical cues in 3D matrices and effects on cell behaviour

Since the overall density, spacing and clustering of ligands have been shown to be implicated in cell adhesion, migration and differentiation in 2D, researchers have hypothesised that the presentation of biochemical cues may influence cell fate in 3D. In order to investigate this, 3D hydrogels functionalised with adhesion ligands or other small molecules have been employed to investigate the effect of density. Although ligands can be incorporated into many types of hydrogels, here we introduce PEG hydrogels, formed by facile click chemistry, and explain their advantages over other hydrogel systems. We then describe how they have been harnessed to regulate ligand presentation and discuss recent advances in biochemical patterning techniques.

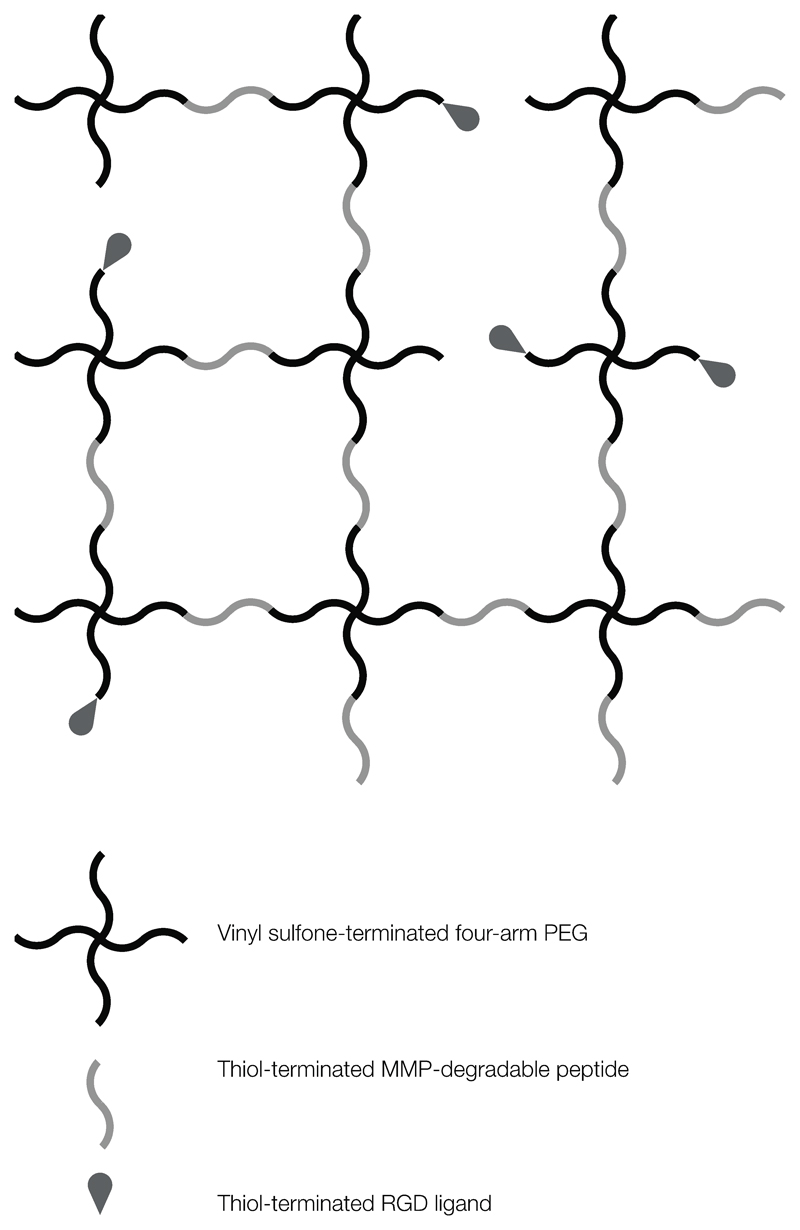

Click chemistry techniques such as thiol-ene and alkyne-azide reactions are frequently employed to form stable, covalently cross-linked matrices and have been used to form hydrogels with varying ligand density. Although thiol-ene chemistry has been in use since the mid 19th century [107], its use in biological applications was pioneered primarily by Hubbell and colleagues over a decade ago. Four-arm-PEG, for example, is widely used for its high degree of orthogonality, biocompatibility, bioinertness and resistance to protein adsorption. As a result, cells encapsulated within non-functionalised PEG are forced into a spherical morphology and cell viability can decrease over time due to anoikis (apoptosis of anchorage-dependent cells due to lack of cell-ECM interaction) [108]. To overcome this and enable cell adhesion and survival, Lutolf et al. (2003) incorporated adhesion ligands and MMP-degradable peptide sequences into four-arm PEG hydrogels [109,110]. These materials, formed by Michael addition under slightly alkaline catalytic conditions, took advantage of the reaction between vinyl sulfone moieties, grafted on the termini of multi-arm PEG macromers, with thiol-containing cysteine residues, positioned at both termini of MMP-degradable peptide cross-linkers, or one end of adhesion ligands (Fig. 7). The groups of Anseth and Bowman have been instrumental in the further development of peptide-functionalised thiol-ene PEG systems that have the advantage over the Michael addition reaction of being performed under milder conditions via photo-polymerisation, including a copper-free variant of the normally toxic alkyne-azide cycloaddition reaction which enables cell encapsulation at neutral pH [111–113].

Fig. 7.

Schematic of RGD-functionalised and MMP-degradable PEG hydrogel formed by click chemistry. Vinyl sulfone-terminated four-arm PEG is first functionalised with thiol-terminated RGD (in high stoichiometric deficit) and then cross-linked via thiol-terminated peptides containing MMP cleavage sites, forming an orthogonal but enzymatically degradable adhesive matrix.

Various ligand-presenting PEG gels, amongst other hydrogel systems, have been used to investigate the effects of ligand concentration in 3D, particularly with regards to stem cell differentiation. As well as inhibiting cell spreading, matrices lacking adhesive cues can influence stem cell fate. For example, ESC encapsulated in ligand-free PEG have been shown to aggregate and form cell-cell interactions, causing differentiation down both endothelial and cardiac lineages, compared to PEG-RGD, which induces more cell-matrix interactions, less aggregation and greater endothelial differentiation [114]. Similarly to some 2D systems [72,76], osteoblast adhesion and spreading [115] and osteogenic differentiation of MSC [116] have also been shown to be highly dependent on ligand presentation. Incorporation of RGD [117] or GFOGER [118] into MMP-degradable PEG hydrogels enhances chondrogenic differentiation of MSC compared to ligand-free gels. Enhanced chondrogenesis, higher Type II collagen synthesis, fewer actin fibres and a more spread morphology have also been observed in MSC encapsulated in PEG-GFOGER compared to PEG-RGD, which induced a stellar morphology with stronger actin staining. Such effects were stronger in MMP-degradable gels than in non-degradable gels [118]. Conversely, chondrogenic differentiation of MSC has been shown to be inhibited in non-degradable, RGD-functionalised alginate [119] and agarose [120] gels. These different responses, however, are likely due to differences in degradation and remodelling between degradable and non-degradable materials, rather than differences in the chemistries of the polymers themselves.

Ligand-functionalised PEG hydrogels have also been utilised to investigate cell behaviour in pathological conditions. For example, PEG-RGD and PEG-laminin1 have been shown to support organotypic morphogenesis of kidney epithelial cells into cysts with a central lumen via β1 integrins, whereas cells encapsulated in non-functionalised PEG did not spread and exhibited atypical morphologies [121]. Cancer cell migration has also been investigated in MMP-degradable PEG-RGD. In these hydrogels, fibrosarcoma cells had a much rounder morphology and were significantly more invasive than dermal fibroblasts, migrating mainly via a non-proteolytic pathway that was partially dependent on RGD concentration within the gels [122]. Unusually, these anchorage-independent cells are able to migrate from a stiff to compliant matrix, but aggregate or reverse direction when moving from a compliant to a stiff region [123]. Taken together, although it is apparent from these findings that matrices containing few or no adhesion ligands do not support efficient cell attachment, at present our understanding of how ligand presentation affects cell responses in 3D is vague. The influence of ligand spacing and clustering on cell fate shown in 2D – as opposed to overall ligand density – indicates that matrices with more highly defined ligand presentation are likely to enable greater control over cellular behaviours in 3D; however, very few experiments to explore such hypotheses have yet been carried out.

In addition to the distribution of adhesive peptides throughout the ECM, other chemical properties of the matrix, such as hydrophilicity can also influence cell behaviour. Whilst these properties have been shown to alter stem cell fate on 2D substrates [20,92], their influence is often overlooked in 3D matrix design, especially in bioinert polymers such as PEG. In 2008 Benoit et al. tethered several different small molecules to PEG in 3D hydrogels. Carboxylic acid groups were chosen to mimic exposed functional groups of cartilage, phosphates were selected as they are implicated in bone mineralization and hydrophobic groups were used to resemble adipose tissue. These functionalities induced chondrogenic, osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of MSC, respectively [17]. These findings further illustrate the importance of non-soluble biochemical features of the cellular microenvironment in directing the cell response and highlight how facile biochemical patterning of small chemicals within hydrogels could be exploited to direct stem cell fate.

Recently, ‘4D’ hydrogels that enable spatial and temporal patterning of specific ligand geometries in 3D – the ‘fourth dimension’ being time – have been developed in order to guide cellular behaviours such as polarisation and migration in real-time [124]. For example, Anseth and colleagues exploited the orthogonality between the copper-free azide-alkyne and thiol-ene systems by creating a PEG hydrogel – formed via the former reaction – that could be selectively [125] and reversibly [126] photo-patterned using the latter reaction, post-gelation. In addition to these and other PEG-based hydrogels [127–129], photo-patterning has also been achieved in ligand-functionalised agarose [130–133], hyaluronic acid [134,135] and alginate [136] hydrogels. This ‘patterning’, however, is limited to micro-scale definition of adhesive regions, rather than spatial orientation of individual ligands on the nano-scale.

Similarly to in 2D, it is likely that not only the density but also the nano-scale spacing and clustering of ligands in 3D will play important roles in directing cellular behaviours such as stem cell differentiation. Studies to examine these hypotheses and experimental models in which to do so, however, are still lacking. However, with recent advances in hydrogel chemistry and increasing understanding of cellular mechanotransduction, this field will likely expand within the next few years. As researchers take advantage of the facile synthesis and modular nature of hydrogels formed by click chemistry, as well as exploit the orthogonal architecture of systems such as multi-arm PEG, biomaterials scientists will be able to gain control of multiple matrix properties – including stiffness, degradability and ligand presentation – both independently from one another and in combination. Such systems will aid in elucidating the distinct role of each characteristic, as well as possible synergistic effects, and will provide new insights in cell-matrix interactions.

4. Concluding remarks and future outlook

Over the past decade, significant advances have been made in deciphering how mechanical, topographical and biochemical cues within cellular micro- and nano-environments regulate cellular behaviours via complex feedback mechanisms involving integrins, FA clustering, actin filaments and downstream signalling cascades. We have discussed the individual effects of cell morphology, substrate stiffness and nano-topography on cellular behaviours and have described how each may be used to gain control over differentiation without the need for differentiation factors. We have also explored findings suggesting that the presentation (spacing and clustering) of ligands in 2D may be harnessed to direct specific cell responses. These studies have provided insight into the interplay between cells and their ECM. However, the unnatural morphology of cells residing on flat surfaces and the unphysiological stiffness of most cell culture substrates is likely to artificially influence the cell response in 2D compared to in vivo.

Early studies involving cell encapsulation within degradable hydrogels are beginning to give a clearer insight into the implications of matrix degradability in 3D, although the effect of matrix stiffness in 3D has yet to be clearly defined. Although some studies have indicated that overall ligand concentration in 3D hydrogels is implicated in directing cellular behaviours, the effect of ligand spacing and clustering in 3D has not yet been examined. The facile nature of click chemistry has the potential to enable an unprecedented high degree of control over ligand spacing and clustering in 3D matrices, with near perfect orthogonality. Furthermore, stiffness and degradability may be varied independently from one another, as well as from other factors, such as ligand presentation. Advances in hydrogel design are therefore likely to enhance our understanding of cell-ECM interactions and should be of particular use for the modelling of a diverse range of disease states, as well as for fundamental cell biology. For example, cellular behaviours may be mapped in processes such as tumour cell migration and invasion, neuron polarisation and neurite sprouting, neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, cardiovascular diseases and osteogenic and chondrogenic differentiation of MSC for treatment of osteoporosis and arthritis. The relative simplicity of synthesis of such materials and the ability to use them for minimally-invasive surgical applications may also enable their use as scaffolds for tissue regeneration in vivo. Hydrogels could be applied in a sterile manner by syringe, with encapsulated patient-derived stem cells for the treatment of a wide range of diseases and injuries that cause tissue damage.

In summary, new approaches to material design are required to improve our understanding of cell-ECM interactions in 3D. By engineering novel hydrogel matrices with independently modulated mechanical and biochemical properties that better simulate the cell niche, we should be able gain considerable control over cellular behaviours in 3D, enabling us to precisely direct stem cell fate. These biomaterials could provide matrices for studying the cell response under normal or pathological conditions, tailored to specific cell types, and could be developed for applications in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgements

EG acknowledges the Wellcome Trust for a Research Career Development Fellowship and support from the Leverhulme Trust.

References

- [1].Wang N, Butler JP, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science. 1993;260:1124–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7684161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Murphy WL, McDevitt TC, Engler AJ. Materials as stem cell regulators. Nature Mater. 2014;13:547–57. doi: 10.1038/nmat3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Arnold M, Cavalcanti-Adam EA, Glass R, Blümmel J, Eck W, Kantlehner M, et al. Activation of integrin function by nanopatterned adhesive interfaces. Chemphyschem. 2004;5:383–8. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200301014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Dalby MJ, Gadegaard N, Tare R, Andar A, Riehle MO, Herzyk P, et al. The control of human mesenchymal cell differentiation using nanoscale symmetry and disorder. Nature Mater. 2007;6:997–1003. doi: 10.1038/nmat2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Mark von der K, Park J, Bauer S, Schmuki P. Nanoscale engineering of biomimetic surfaces: cues from the extracellular matrix. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:131–53. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0896-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Cukierman E. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294:1708–12. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dusseiller MR, Smith ML, Vogel V, Textor M. Microfabricated three-dimensional environments for single cell studies. Biointerphases. 2006;1:P1. doi: 10.1116/1.2190698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ochsner M, Textor M, Vogel V, Smith ML. Dimensionality controls cytoskeleton assembly and metabolism of fibroblast cells in response to rigidity and shape. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Li Y, Rodrigues J, Tomás H. Injectable and biodegradable hydrogels: gelation, biodegradation and biomedical applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2193. doi: 10.1039/c1cs15203c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Place ES, George JH, Williams CK, Stevens MM. Synthetic polymer scaffolds for tissue engineering. Chem Soc Rev. 2009;38:1139–51. doi: 10.1039/b811392k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Aydin D, Louban I, Perschmann N, Blümmel J, Lohmüller T, Cavalcanti-Adam EA, et al. Polymeric substrates with tunable elasticity and nanoscopically controlled biomolecule presentation. Langmuir. 2010;26:15472–80. doi: 10.1021/la103065x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Langer R, Vacanti JP. Tissue engineering. Science. 1993;260:920–6. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Place ES, Evans ND, Stevens MM. Complexity in biomaterials for tissue engineering. Nature Mater. 2009;8:457–70. doi: 10.1038/nmat2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mason C, Dunnill P. A brief definition of regenerative medicine. Regen Med. 2008;3:1–5. doi: 10.2217/17460751.3.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].McNamara LE, McMurray RJ, Biggs MJP, Kantawong F, Oreffo ROC, Dalby MJ. Nanotopographical control of stem cell differentiation. J Tissue Eng. 2010;1:120623–3. doi: 10.4061/2010/120623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dingal PCDP, Discher DE. Combining insoluble and soluble factors to steer stem cell fate. Nature Mater. 2014;13:532–7. doi: 10.1038/nmat3997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Benoit DSW, Schwartz MP, Durney AR, Anseth KS. Small functional groups for controlled differentiation of hydrogel-encapsulated human mesenchymal stem cells. Nature Mater. 2008;7:816–23. doi: 10.1038/nmat2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Oh S, Brammer KS, Li YSJ, Teng D, Engler AJ, Chien S, et al. Stem cell fate dictated solely by altered nanotube dimension. Proc Natl Acad Sci USa. 2009;106:2130–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813200106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Watt FM, Jordan PW, O'Neill CH. Cell shape controls terminal differentiation of human epidermal keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USa. 1988;85:5576–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.15.5576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McBeath R, Pirone DM, Nelson CM, Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment. Dev Cell. 2004;6:483–95. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hytönen VP, Wehrle-Haller B. Protein conformation as a regulator of cell-matrix adhesion. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2014;16:6342–57. doi: 10.1039/c3cp54884h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Kong H-J, Polte TR, Alsberg E, Mooney DJ. FRET measurements of cell-traction forces and nano-scale clustering of adhesion ligands varied by substrate stiffness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USa. 2005;102:4300–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Huebsch N, Arany PR, Mao AS, Shvartsman D, Ali OA, Bencherif SA, et al. Harnessing traction-mediated manipulation of the cell/matrix interface to control stem-cell fate. Nature Mater. 2010;9:518–26. doi: 10.1038/nmat2732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Khetan S, Guvendiren M, Legant WR, Cohen DM, Chen CS, Burdick JA. Degradation-mediated cellular traction directs stem cell fate in covalently crosslinked three-dimensional hydrogels. Nature Mater. 2013;12:458–65. doi: 10.1038/nmat3586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Alberts B, Johnson A, Lewis J, Raff M, Roberts K. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4 ed. New York: Garland Science, New York; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Gelse K, Pöschl E, Aigner T. Collagens—structure, function, and biosynthesis. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2003;55:1531–46. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–87. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wang N, Tytell JD, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:75–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].DuFort CC, Paszek MJ, Weaver VM. Balancing forces: architectural control of mechanotransduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:308–19. doi: 10.1038/nrm3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Puklin-Faucher E, Vogel V. Integrin activation dynamics between the RGD-binding site and the headpiece hinge. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:36557–68. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Huang S, Ingber DE. The structural and mechanical complexity of cell-growth control. Nature Cell Biol. 1999;1:E131–8. doi: 10.1038/13043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Brakebusch C, Fässler R. The integrin–actin connection, an eternal love affair. Embo J. 2003;22:2324–33. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Yu C-H, Law JBK, Suryana M, Low HY, Sheetz MP. Early integrin binding to Arg-Gly-Asp peptide activates actin polymerization and contractile movement that stimulates outward translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USa. 2011;108:20585–90. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1109485108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Maheshwari G, Brown G, Lauffenburger DA, Wells A, Griffith LG. Cell adhesion and motility depend on nanoscale RGD clustering. J Cell Sci. 2000;113(Pt 10):1677–86. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Irvine DJ, Mayes AM, Griffith LG. Nanoscale clustering of RGD peptides at surfaces using comb polymers. 1. Synthesis and characterization of comb thin films. Biomacromolecules. 2001;2:85–94. doi: 10.1021/bm005584b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Irvine DJ, Ruzette A-VG, Mayes AM, Griffith LG. Nanoscale clustering of RGD peptides at surfaces using comb polymers. 2. Surface segregation of comb polymers in polylactide. Biomacromolecules. 2001;2:545–56. doi: 10.1021/bm015510f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Koo LY, Irvine DJ, Mayes AM, Lauffenburger DA, Griffith LG. Co-regulation of cell adhesion by nanoscale RGD organization and mechanical stimulus. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1423–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.7.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Fraley SI, Feng Y, Krishnamurthy R, Kim D-H, Celedon A, Longmore GD, et al. A distinctive role for focal adhesion proteins in three-dimensional cell motility. Nature Cell Biol. 2010;12:598–604. doi: 10.1038/ncb2062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ruoslahti E. RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:697–715. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Humphries JD. Integrin ligands at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3901–3. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Altrock E, Muth CA, Klein G, Spatz JP, Lee-Thedieck C. The significance of integrin ligand nanopatterning on lipid raft clustering in hematopoietic stem cells. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3107–18. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Stevens MM. Exploring and engineering the cell surface interface. Science. 2005;310:1135–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1106587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Weiner S, Wagner HD. The material bone: structure-mechanical function relations. Annu Rev Mater Sci. 1998;28:271–98. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Bozec L, van der Heijden G, Horton M. Collagen fibrils: nanoscale ropes. Biophys J. 2007;92:70–5. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.085704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wang W, Liu Q, Zhang Y, Zhao L. Involvement of ILK/ERK1/2 and ILK/p38 pathways in mediating the enhanced osteoblast differentiation by micro/nanotopography. Acta Biomaterialia. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Geblinger D, Addadi L, Geiger B. Nano-topography sensing by osteoclasts. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1503–10. doi: 10.1242/jcs.060954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Gross KA, Muller D, Lucas H, Haynes DR. Osteoclast resorption of thermal spray hydoxyapatite coatings is influenced by surface topography. Acta Biomaterialia. 2012;8:1948–56. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2012.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Dalby MJ, Gadegaard N, Oreffo ROC. Harnessing nanotopography and integrin–matrixinteractions to influence stem cell fate. Nature Mater. 2014;13:558–69. doi: 10.1038/nmat3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Rajnicek A, Britland S, McCaig C. Contact guidance of CNS neurites on grooved quartz: influence of groove dimensions, neuronal age and cell type. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 23):2905–13. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.23.2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lee MR, Kwon KW, Jung H, Kim HN, Suh K, Kim K, et al. Direct differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into selective neurons on nanoscale ridge/groove pattern arrays. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4360–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Yang K, Jung K, Ko E, Kim J, Park KI, Kim J, et al. Nanotopographical manipulation of focal adhesion formation for enhanced differentiation of human neural stem cells. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5:10529–40. doi: 10.1021/am402156f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Andersson A-S, Bäckhed F, Euler von A, Richter-Dahlfors A, Sutherland DS, Kasemo B. Nanoscale features influence epithelial cell morphology and cytokine production. Biomaterials. 2003;24:3427–36. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00208-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Wilson MJ, Jiang Y, Yanez-Soto B, Liliensiek SJ, Murphy WL, Nealey PF. Arrays of topographically and peptide-functionalized hydrogels for analysis of biomimetic extracellular matrix properties. J Vac Sci Technol B Nanotechnol Microelectron. 2012;30:6F903. doi: 10.1116/1.4762842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Yanez-Soto B, Liliensiek SJ, Gasiorowski JZ, Murphy CJ, Nealey PF. The influence of substrate topography on the migration of corneal epithelial wound borders. Biomaterials. 2013;34:9244–51. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Bettinger CJ, Langer R, Borenstein JT. Engineering substrate topography at the micro- and nanoscale to control cell function. Angew Chem. 2009;48:5406–15. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Yim EKF, Pang SW, Leong KW. Synthetic nanostructures inducing differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells into neuronal lineage. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:1820–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Dalby MJ, Yarwood SJ, Riehle MO, Johnstone HJH, Affrossman S, Curtis ASG. Increasing fibroblast response to materials using nanotopography: morphological and genetic measurements of cell response to 13-nm-high polymer demixed islands. Exp Cell Res. 2002;276:1–9. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Dalby MJ, Childs S, Riehle MO, Johnstone HJH, Affrossman S, Curtis ASG. Fibroblast reaction to island topography: changes in cytoskeleton and morphology with time. Biomaterials. 2003;24:927–35. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Dalby MJ, McCloy D, Robertson M, Agheli H, Sutherland DS, Affrossman S, et al. Osteoprogenitor response to semi-ordered and random nanotopographies. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2980–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].McMurray RJ, Gadegaard N, Tsimbouri PM, Burgess KV, McNamara LE, Tare R, et al. Nanoscale surfaces for the long-term maintenance of mesenchymal stem cell phenotype and multipotency. Nature Mater. 2011;10:637–44. doi: 10.1038/nmat3058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Peng R, Yao X, Ding J. Effect of cell anisotropy on differentiation of stem cells on micropatterned surfaces through the controlled single cell adhesion. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8048–57. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Théry M, Pépin A, Dressaire E, Chen Y, Bornens M. Cell distribution of stress fibres in response to the geometry of the adhesive environment. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2006;63:341–55. doi: 10.1002/cm.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Lehnert D. Cell behaviour on micropatterned substrata: limits of extracellular matrix geometry for spreading and adhesion. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:41–52. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Marklein RA, Burdick JA. Spatially controlled hydrogel mechanics to modulate stem cell interactions. Soft Matter. 2009;6:136. [Google Scholar]

- [65].Lutz R, Pataky K, Gadhari N, Marelli M, Brugger J, Chiquet M. Nano-stenciled RGD-gold patterns that inhibit focal contact maturation induce lamellipodia formation in fibroblasts. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e25459. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Glass R, Möller M, Spatz JP. Block copolymer micelle nanolithography. Nanotechnology. 2003;14:1153. [Google Scholar]

- [67].Graeter SV, Huang J, Perschmann N, López-García M, Kessler H, Ding J, et al. Mimicking cellular environments by nanostructured soft interfaces. Nano Lett. 2007;7:1413–8. doi: 10.1021/nl070098g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Erb EM, Tangemann K, Bohrmann B, Müller B, Engel J. Integrin αIIbβ3 reconstituted into lipid bilayers is nonclustered in its activated state but clusters after fibrinogen binding. Biochemistry. 1997;36:7395–402. doi: 10.1021/bi9702187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Jakubick VC, Arnold M, Cavalcanti-Adam EA, López-García M, Kessler H, Spatz JP. Cell adhesion and polarisation on molecularly defined spacing gradient surfaces of cyclic RGDfK peptide patches. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:743–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2008.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Cavalcanti-Adam EA, Micoulet A, Blümmel J, Auernheimer J, Kessler H, Spatz JP. Lateral spacing of integrin ligands influences cell spreading and focal adhesion assembly. Eur J Cell Biol. 2006;85:219–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2005.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Arnold M, Hirschfeld-Warneken VC, Lohmüller T, Heil P, Blümmel J, Cavalcanti-Adam EA, et al. Induction of cell polarization and migration by a gradient of nanoscale variations in adhesive ligand spacing. Nano Lett. 2008;8:2063–9. doi: 10.1021/nl801483w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Frith JE, Mills RJ, Cooper-White JJ. Lateral spacing of adhesion peptides influences human mesenchymal stem cell behaviour. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:317–27. doi: 10.1242/jcs.087916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Delcassian D, Depoil D, Rudnicka D, Liu M, Davis DM, Dustin ML, et al. Nanoscale ligand spacing influences receptor triggering in T cells and NK cells. Nano Lett. 2013;13:5608–14. doi: 10.1021/nl403252x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Deeg JA, Louban I, Aydin D, Selhuber-Unkel C, Kessler H, Spatz JP. Impact of local versus global ligand density on cellular adhesion. Nano Lett. 2011;11:1469–76. doi: 10.1021/nl104079r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Schvartzman M, Palma M, Sable J, Abramson J, Hu X, Sheetz MP, et al. Nanolithographic control of the spatial organization of cellular adhesion receptors at the single-molecule level. Nano Lett. 2011;11:1306–12. doi: 10.1021/nl104378f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Lee KY, Alsberg E, Hsiong SX, Comisar WA, Linderman JJ, Ziff R, et al. Nanoscale adhesion ligand organization regulates osteoblast proliferation and differentiation. Nano Lett. 2004;4:1501–6. doi: 10.1021/nl0493592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Brinkerhoff CJ, Linderman JJ. Integrin dimerization and ligand organization: key components in integrin clustering for cell adhesion. Tissue Eng. 2005;11:865–76. doi: 10.1089/ten.2005.11.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Comisar WA, Hsiong SX, Kong H-J, Mooney DJ, Linderman JJ. Multi-scale modeling to predict ligand presentation within RGD nanopatterned hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2006;27:2322–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.10.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Comisar WA, Kazmers NH, Mooney DJ, Linderman JJ. Engineering RGD nanopatterned hydrogels to control preosteoblast behavior: a combined computational and experimental approach. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4409–17. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Comisar WA, Mooney DJ, Linderman JJ. Integrin organization: linking adhesion ligand nanopatterns with altered cell responses. J Theor Biol. 2011;274:120–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Geiger B, Spatz JP, Bershadsky AD. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Wang H-B, Dembo M, Wang Y-L. Substrate flexibility regulates growth and apoptosis of normal but not transformed cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2000;279:C1345–50. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.279.5.C1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Elosegui-Artola A, Bazellières E, Allen MD, Andreu I, Oria R, Sunyer R, et al. Rigidity sensing and adaptation through regulation of integrin types. Nature Mater. 2014 doi: 10.1038/nmat3960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Choi K, Kuhn JL, Ciarelli MJ, Goldstein SA. The elastic moduli of human subchondral, trabecular, and cortical bone tissue and the size-dependency of cortical bone modulus. J Biomech. 1990;23:1103–13. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90003-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Callister WD, Rethwisch DG. Fundamentals of Materials Science and Engineering. Fourth Edition. Somerset, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., USA; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [87].Pelham RJ, Wang YL. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USa. 1997;94:13661–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Discher DE. Tissue cells feel and respond to the stiffness of their substrate. Science. 2005;310:1139–43. doi: 10.1126/science.1116995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]