Abstract

Kv4 channel complexes mediate the neuronal somatodendritic A-type K+ current (ISA), which plays pivotal roles in dendritic signal integration. These complexes are composed of pore-forming voltage-gated α-subunits (Shal/Kv4) and at least two classes of auxiliary β-subunits: KChIPs (K+-Channel-Interacting-Proteins) and DPLPs (Dipeptidyl-Peptidase-Like-Proteins). Here, we review our investigations of Kv4 gating mechanisms and functional remodeling by specific auxiliary β-subunits. Namely, we have concluded that: (1) the Kv4 channel complex employs novel alternative mechanisms of closed-state inactivation; (2) the intracellular Zn2+ site in the T1 domain undergoes a conformational change tightly coupled to voltage-dependent gating and is targeted by nitrosative modulation; and (3) discrete and specific interactions mediate the effects of KChIPs and DPLPs on activation, inactivation and permeation of Kv4 channels. These studies are shedding new light on the molecular bases of ISA function and regulation.

Keywords: Voltage-gated potassium channel, Gating, Inactivation, Auxiliary β subunits, A-type potassium current, T1 domain

Shal/Kv4 Channels are Highly-conserved Throughout the Animal Kingdom

In the super-family of voltage-gated K+ channels (Kv channels) of eukaryotes, there are four closely related subfamilies: Kv1 (Shaker), Kv2 (Shab), Kv3 (Shaw) and Kv4 (Shal) [31, 107]. All Kv channels in these subfamilies are tetrameric and share three well-defined domains in the pore-forming α-subunit (N- to C-terminus): the T1 domain (T1), the voltage-sensing domain (VSD) and the pore domain (PD) [49, 75] (Fig. 1). Whereas the transmembrane VSD and PD are found in other Kv channels, the intra-cellular T1 is restricted to the four subfamilies outlined above. However, there are important distinctions between these Kv channels. Kv1, Kv2 and Kv3 channels mediate a broad range of electrophysiological phenotypes, which include fast and slow inactivating outward K+ currents (A-type and delayed rectifier-type, respectively). In contrast, Shal/Kv4 channels throughout the animal kingdom, exhibit highly conserved primary structure and, with or without auxiliary subunits (see below), the vast majority of them mediates fast A-type K+ currents [5, 54, 92, 112]. Although Kv4 channels are found in various tissues in mammalian organisms [1, 90, 95], they are broadly found in neurons of primitive and advanced animals [8, 14, 35, 50, 54, 107, 108, 122]. Therefore, Shal/Kv4 channels are likely to determine fundamental electrical properties of neurons.

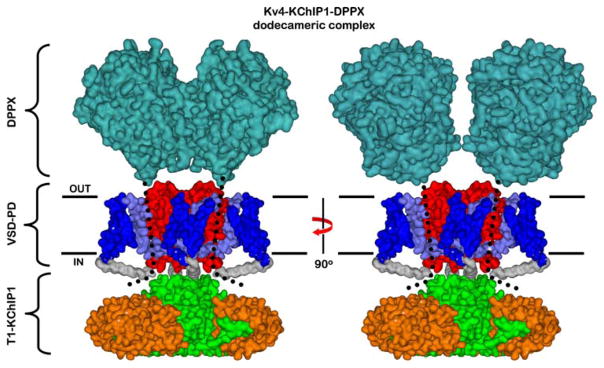

Fig. 1.

Structural model of the Kv4 channel complex. This model combines the crystal structures of the DPPX dimer (blue-green, extracellular C-terminal domains only), Kv 1.2 tetramer (blue and red, VSD and PD domains, respectively; S4 and S4S5 linker is light blue) and the T1-KChlP-1 octameric complexes (green and orange, T1 and KChlP-1, respectively); and assumes an overall dodecameric stoichiometry) The dotted line represents the putative location of the DPPX transmembrane segment and intracellular N-terminus. Note that KChlP-1 sequesters and immobilizes the N-terminus of the Kv4 channel (Note: For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the online version of this article)

Numerous studies over the last two decades have focused on investigating bacterial K+ channels, Shaker-B Kv channels and Shaker-related Kv1 channels. The resulting breakthroughs have revealed the molecular bases of ionic selectivity, voltage-dependent activation gating and open-state inactivation [13, 30, 79, 135]. However, much less is known about the mechanisms that underlie closed-state inactivation, the gating role of the T1 domain and the remodeling/regulatory roles of Kv4 auxiliary β-subunits. The latter is especially important because most Kv channels co-assemble with diverse auxiliary β-subunits to form macromolecular complexes in excitable tissues; and these β-subunits ultimately determine the localization, expression and specific functional properties of the native K+ conductances [40, 54, 67, 69, 99].

The Somatodendritic A-type K+ Channel

Since the discovery of the A-type K+ current in mollusk neurons [28, 39, 89], a wealth of studies have characterized the counterpart in mammalian brain and the nervous system of other organisms [14, 54, 106]. The somatodendritic A-type K+ current (ISA) is expressed in the soma and dendrites of central neurons; typically, it activates and inactivates rapidly in response to membrane depolarization, operates in the subthreshold range of membrane potentials, is typically inactivated at the resting membrane potential, and its density increases gradually from the soma to the distal dendrites in CA1 hippocampal neurons [42, 113]. In different neuron types, ISA plays many roles; for instance, it prolongs the latency to the first spike in a train of action potentials, slows repetitive spike firing, shortens action potentials and attenuates back propagating action potentials [12, 14, 20, 27, 42, 57, 58, 61, 80, 81, 84, 110, 118, 129]. These roles can influence dendritic excitability, somatodendritic signal integration and long-term potentiation [14, 25, 57, 60]. For instance, ISA controls the propagation of dendritic plateau potentials at branching points by acting as gate-keepers in distal dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons [20]. Most likely, Kv4 pore-forming α-subunits underlie ISA in the central and peripheral nervous systems. Many studies have isolated ISA electrophysiologically and identified Kv4 genes, transcripts and proteins by applying in situ hybridization, single-cell reverse-transcription-polymerase-chain-reaction (RT-PCR) and immunohistochemistry [20, 25, 46, 60, 61, 68; 74, 80, 81, 83, 103, 111, 114, 118, 121]. Furthermore, knock-down, knock-out and over-expression approaches have established the contribution of Kv4 channels to ISA [20, 25, 46, 60, 61, 68, 80, 114]. We will later discuss the additional contribution of at least two classes of specific auxiliary β-subunits to the neuronal Kv4 channel complex.

Inactivation of Kv4 Channels: Two Gates in One?

Inactivation of voltage-gated ion channels is the auto-regulatory time-dependent process that shuts down the corresponding conductances in response to a prolonged or sustained membrane depolarization [41]. In Kv4 channels, inactivation at steady-state is nearly complete; and a relatively fast development of inactivation is a hallmark of all known members of the Shal/Kv4 subfamily [54]. Fast recovery from inactivation at hyperpolarized membrane potentials removes Kv4 channel steady-state inactivation in tens to hundreds of milliseconds. That is in contrast to most other Kv channels, which require seconds to tens of seconds to recover from inactivation. Although inactivation of Shaker-B and Kv1 channels is generally well understood at the molecular level [26, 29, 30, 44, 45, 70, 91, 93, 94, 133, 135], the mechanisms of inactivation of Kv4 channels seem distinct and remain unsolved [54]. In heterologous expression systems and in the absence of auxiliary β-subunits, Kv4 channels may undergo open- and closed-state inactivation [3, 10, 128]. These processes, however, exhibit features inconsistent with the presence of classical N- and P/C-type mechanisms of inactivation, as found in Shaker-B and Kv1 channels [36, 51, 54, 56]. In native Kv4 channel complexes particularly, open-state N-type inactivation determined by the channel’s proximal N-terminus is unlikely because KChIPs sequester and immobilize this region constitutively [2, 9, 98, 127].

Another hallmark of native and recombinant Kv4 channels coexpressed with KChIP-1 is that elevated external K+ accelerates the development of inactivation [59, 63], which appears to contradict the predictions of a “foot-in-the-door” mechanism acting on classical P/C-type inactivation [78, 132]. In this mechanism, K+ occupies an external pore site and thereby slows inactivation by preventing constriction of the external mouth of the channel. We found that modulation of Kv4 channels by external K+ involves a saturable site with a KD of the order of 8 mM; and that this site is possibly located in the selectivity filter because permeant cations are more effective modulators than poor permeant cations (K+ = Rb+ = NH4+ > Cs+ > Na+) [59]. We explained these observations quantitatively by assuming that Kv4 channels exhibit profound closed-state inactivation allosterically coupled to the voltage-dependent activation pathway, and a separate set of unstable closed states connected to all states in the activation pathway [59]. The key of this solution is that transiting to this set of unstable closed states is less likely as the concentration of external K+ increases (or other permeant cation). These closed states may correspond to vestigial P/C-type inactivation in Kv4 channels. Thus, the Kv4 pore can fluctuate between constricted and conducting conformations before the channel populates a distinct closed-inactivated state at steady-state. In this scenario, acceleration of inactivation by external K+ results indirectly from the inherent enhancement of the open probability caused by the inhibition of vestigial P/C-type inactivation. An enhanced open probability will promote inactivation from a pre-open closed state because there is no open-state inactivation (in the presence of KChIP-1; see below) and channel closing is significant. This mechanism implies, as proposed before [54], that the structure of the selectivity filter in Kv4 channels is intrinsically more stable than that of Shaker-B, Kv1 and certain bacterial K+ channels, which allowed alternative mechanisms of closed-state inactivation to evolve.

Unusual slowing of the apparent rate of macroscopic inactivation as the membrane potential becomes progressively more depolarized is an additional hallmark of Kv4 channels. Particularly, this feature is apparent when Kv4 channels are coexpressed with KChIP-1 or KChIP-3 [9, 52, 59] and has been reported in several studies of neuronal ISA [42, 64, 73, 83]. Such a behavior is a specific central prediction of preferential inactivation from a pre-open closed-state, which has been demonstrated quantitatively for Kv4.3 and Kv4.2 channels coexpressed with KChIP-1 in Xenopus oocytes and mammalian cells, respectively [59] (Amarillo et al., J. Physiol., in press). Essentially, the voltage-dependent slowing of the inactivation rate occurs because the concerted opening-closing step of the channel is weakly voltage-dependent. Therefore, as the open probability increases gradually with progressive depolarizations of the membrane potential, the occupancy of the inactivation-permissive pre-open closed state decreases gradually and, consequently, the development of inactivation is slowed in a weakly voltage-dependent manner. Further strong support for a prominent pathway of closed-state inactivation in Kv4 channels comes from recent gating current experiments (Dougherty, De Santiago-Castillo and Covarrubias, J. Gen. Physiol., 131:257–273). We showed that slight—modest depolarizations over a hyper-polarized range of membrane potentials (−110 to −70 mV) induce a profound apparent loss of gating charge (Q-loss). Critically, the kinetics of Q-loss precisely follows the time course of current inactivation in a manner that is independent of the channel’s N-terminal region.

In light of the observations summarized above, Kv4 channels are more likely to employ alternative and poorly understood mechanisms of closed-state inactivation. A current working hypothesis proposes that the Kv4 channel inactivation mechanism is analogous to that proposed for closed-state inactivation of HCN channels [54, 56, 59, 115]. Basically, the main internal activation gate of the channel (A-gate) conducts two separate jobs, and therefore, it can control both activation and inactivation. Whether it does one or the other depends on the strength of the electromechanical coupling between the voltage sensor and the A-gate [76]. This coupling is thought to be the mechanism responsible for voltage-dependent Kv channel activation [97]. However, weakening of the underlying molecular interactions over time during a sustained depolarization would promote “dislocation” of the voltage sensor and an apparent Q-loss, rendering the A-gate reluctant to opening (i.e., the A-gate is desensitized to voltage) [115]. Although the collective evidence in favor of a non-N-type and non-P/C-type mechanism of preferential closed-state inactivation in Kv4 channels is strong, alternative hypotheses have been proposed by others and the problem remains controversial [34, 95, 116, 128].

Gating at the Portals of the K+ Pore, the Intracellular T1 Domain of Kv4 Channels

The multifunctional T1 domain of Kv channels encompasses ~100 amino acids within the intracellular N-terminal region of the pore-forming protein. It determines the specificity of subunit assembly within a subfamily [71, 131]; acts as the anchoring site for auxiliary subunits [21, 38]; controls axonal targeting [37, 104]; and regulates activation gating [32, 85, 105, 124, 125]. The T1 domain assembly in the Kv channel appears as a “hanging gondola” connected to the transmembrane core (VSD + PD) via the T1-S1 linkers. These linkers form lateral portals that allow K+ ions to access the internal mouth of the channel when the main A-gate opens [65, 75]. Although T1 domains are topologically similar among Kv channels, an important difference between those from Kv1 and non-Kv1 channels (Kv2, Kv3 and Kv4) is that only the latter contain an inter-subunit Zn2+ binding site involving the characteristic motif HX(5)CX(20)CC [15, 66, 88] (Fig. 2). While the cysteine doublet and the histidine are from the same subunit at the intersubunit interface, the third cysteine is from the neighboring subunit. This site was first identified in the crystal structure of an isolated Kv3-T1 domain and high-affinity Zn2+ binding appeared necessary to maintain the tetrameric quaternary structure [15, 48, 119]. In intact Kv4 channels coexpressed with KChIP-1 and DPPX-S, however, this site is not Zn2+-bound constitutively or Zn2+ is partially liganded because thiol-specific reagents (e.g., MTSET) can modify the critical cysteines and mild oxidizing conditions readily induce a disulfide-bond across the intersubunit interface [124, 125]. Otherwise, tightly bound Zn2+ would have protected all critical cysteines against oxidation. These chemical modifications inhibit channel activity profoundly; and the time-dependent inhibition by MTSET is also state-and voltage-dependent [124, 125]. The accessibility to the Zn2+ site cysteines is ~300–400-fold larger in the activated state relative to the resting or inactivated states. In contrast, the cysteine accessibility differs only by ~twofold between resting and inactivated states. Furthermore, the voltage dependence of the accessibility followed the voltage dependence of the peak conductance faithfully. These results were surprising because the Zn2+ binding site is apparently distant from VSD and PD elements of the channel that are more directly involved in voltage-dependent gating of the channel. We have proposed that the Kv4-T1 domain undergoes a significant conformational change that is tightly coupled to voltage-dependent gating [124]; and the Kv1-T1 domain may undergo similar rearrangements [32, 85, 105]. A much smaller difference between the cysteine accessibilities of the resting and inactivated states is consistent with the presence of closed-state inactivation in Kv4 channels.

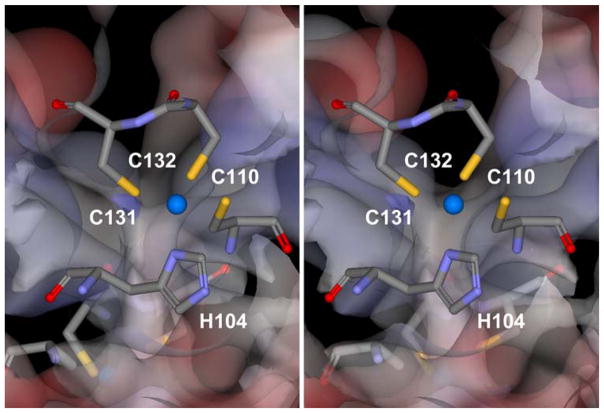

Fig. 2.

Stereo view of the interfacial Zn2+ binding site in the T1 domain of the Kv4.1 channel. A stick representation of the coordinating residues is shown. C131, C132 and H104 are from the same subunit, and C110 is from the neighboring subunit. The blue sphere represents a Zn2+ ion in the binding site. Although the isolated T1 domain oligomer is typically Zn2+-bound, the T1 domain in the intact Kv4.1 channel appears to be Zn2+-free or partially liganded (see text) (Note: For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the online version of this article)

The crystal structures of Kv1 channels and the Kv4-T1 domain [75, 77, 88, 109] suggest a working hypothesis of the putative movements that may underlie the dramatic accessibility changes in the interfacial T1 Zn2+ site. For instance, voltage-dependent rearrangements in the VSD may be transmitted to the T1 domain via the T1-S1 linker. This linker begins a few residues downstream from the Zn2+ binding motif. Moreover, it is also possible that the space between the T1 domain and the transmembrane domains is narrower when the channels are closed or closed-inactivated; and, therefore, the lateral intracellular portals are ajar (as suggested by molecular dynamic simulations; Treptow et al., J. Phys. Chem. B., in press). Upon voltage-dependent activation, VSD movements may propagate to the T1 domain. As a result, there is a rearrangement in the interfacial Zn2+ site and the T1 and transmembrane domains separate. Then, the internal Agate opens, the lateral portals widen, and the solvent accessibility of the interfacial Zn2+ site is dramatically increased. In this scenario, the T1 domain is an integral moving part of the gating machinery in Kv4 channels.

To elucidate the physiological significance of the conformational change in the Zn2+ site of the Kv4-T1 domain, we investigated the modulation of the Kv4.1 ternary channel complex (Fig. 1) by nitrosative stress. In a manner analogous to oxidative stress, reactive nitrogen oxide species (RNOS) derived from nitric oxide (NO) metabolism can cause nitrosative stress in proteins [102]. The intra-cellular application of a NO donor (MAHMA-NONOate) to inside-out patches induces rapid inhibition of Kv4.1 channels [126]. To observe this inhibition, it is sufficient and necessary to have two cysteines across the T1 inter-subunit interface (C110 and C132), and intracellular Zn2+ antagonizes it [126] (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the addition of reducing reagents (reduced glutathione, GSH; or dithio-threitol, DTT) reverses the NO-induced inhibition. Therefore, we have proposed that the inhibition of the channel by nitrosative regulation results from the formation of a disulfide bond between C110 and C132, which straight-jackets the T1–T1 interface. Supporting this interpretation, these cysteines are only a few Ǻ from each other (Fig. 2), and we detected the reversible formation of high-order oligomers in the presence of NO when C110 and C132 were available only [126]. Straight-jacketing the T1–T1 interface is responsible for the inhibition of the channel by NO because it presumably prevents the inter-subunit T1 displacements associated with activation gating. These results suggest for the first time that the cross-talk between NO and Zn2+ [17, 47, 72, 82] may also be critical for redox regulation of ISA in the nervous system.

Kv4 Channel β-Subunits, Integral Remodeling Parts of ISA

KChIPs (K+-Channel-Interacting-Proteins) and DPLPs (Dipeptidyl-Peptidase-Like-Proteins) encompass two distinct families of integral auxiliary β-subunits of neuronal Kv4 channels [54]. KChIPs are cytosolic small-molecular-weight calcium binding proteins related to the neuronal calcium sensor [2, 18, 19]. Since the discovery of KChIPs [2], subsequent studies have reported additional closely related genes and many alternative splice variants [4, 16, 18, 43, 96, 120, 123]. DPLPs are single-pass membrane proteins related to the cell adhesion protein CD26 and the dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPPIV) [62]. Two distinct DPLPs have been identified as auxiliary β-subunits of Kv4 channels (DPPX and DPPY) and several alternative splice variants have also been discovered [53, 55, 86, 87, 134]. Recent studies have reported crystal structures of KChIP-1 and DPPX [98, 109, 127, 136].

These auxiliary β-subunits produce a plethora of biochemical and functional changes, which influence activation and inactivation gating, and voltage dependence [54]. Promoting the trafficking of Kv4 subunits to the plasma membrane is a common denominator of most KChIPs and DPLPs [2, 54, 55, 87, 134]. KChIP4a is a notable exception that does not promote surface expression [43]. The most common and dramatic effects of KChIPs are to slow the fast phase of macroscopic inactivation and accelerate the recovery from inactivation. The slowing of fast inactivation results from the tight binding of the cytosolic Kv4 N-terminus to the core of KChIPs (interacting site 1) [4, 21, 98, 101, 127, 136]. The free Kv4 N-terminus may otherwise act as an inactivation domain [36, 51]. Thus, the constitutive sequestration and immobilization of the Kv4 N-terminal inactivation domain (Kv4 NT-ID) is directly responsible for slower inactivation [9, 59]. The molecular bases of accelerated recovery from inactivation are not understood; and the accelerating effects of KChIP-1 on the slow phase(s) of inactivation and channel closing are also intriguing [7, 9, 59]. It is possible that the sequestration of the Kv4 NT-ID by its binding to KChIP-1 relieves a “foot-in-the-door” effect at the A-gate with a dual role on activation and closed-state inactivation (see above). Thus, closing and slow inactivation are eased without the physical interference from the Kv4 NT-ID at the inner mouth of the channel.

KChIPs may also help to stabilize the T1–T1 interface by clamping together two neighboring T1 domains (interacting site 2) [98, 127]. Structural studies suggest that the main role of high-affinity Ca2+/Mg2+ binding in KChIPs is to maintain their compact tertiary structure, which is necessary for proper coassembly with Kv4 channels [23, 98]. A general dynamic role of Ca2+ binding on the functional effects of most KChIPs seems doubtful [96].

Functionally, the common denominator of DPLPs is to shift the voltage dependence of activation and inactivation toward more negative membrane potentials [52, 53, 55, 86, 87, 134]. We hypothesized that this change results from a direct interaction between the DPLPs’ single transmembrane segment and the channel’s VSD, as suggested by previous reports [100, 134]. To investigate this hypothesis, we implemented a strategy to measure Kv4 gating currents for the first time [33]. This method takes advantage of an engineered charybdotoxin (CTX) binding site in the pore of the Kv4.2 channel. Thus, we isolated the gating currents by blocking the ionic K+ current upon bath application of CTX. These experiments showed that DPPX-S accelerates the relaxation of the gating currents and shifts the voltage-dependence of gating charge (Q) movement toward more negative membrane potentials; and this shift was quantitatively comparable to that of the peak conductance-voltage relation (−26 mV) [33]. Further kinetic analysis revealed that these observations are readily explained by assuming that DPPX-S destabilizes the resting conformations of the voltage sensors through a catalytic effect that changes the activation pathway’s energetic landscape [33]. An attractive possibility that emerges from this study is that the transmembrane segment of DPPX-S evolved to become an integral voltage sensor interacting protein of Kv4 channels. The potent effect of DPPX-S on voltage-dependent gating may also be sufficient to explain acceleration of inactivation coupled to activation [33, 87].

Possibly, the functional diversity and specificity among DPLPs is in part dictated by their intracellular N-terminal region. For instance, it has been suggested that the proximal N-terminus of DPPY-a determines voltage-dependent ultra-fast inactivation of Kv4.2 channels coexpressed with this auxiliary subunit [53]. Also, we have found that acidic amino acids within the N-terminus of DPPX-S may confer higher unitary conductance to Kv4.3 and Kv4.2 channels (Kaulin, Rocha, Rudy and Covarrubias, unpublished). This result is significant because the unitary conductance of Kv4 channels coexpressed with DPPX-S agrees closely with that of the neuronal native counterpart (6–8 pS) [11, 24, 42, 117] and is about 50–100% larger than that of the Kv4 channels expressed alone [9, 43, 56].

Perspective

The cloning and characterization of the first Shal gene from Drosophila melanogaster was reported in 1990 [130]. Subsequently, the first mammalian homologues were also identified, cloned and characterized [5, 92, 112]; and evidence of putative Kv4 auxiliary β-subunits was published in 1993 and 1994 [22, 111]. In the last 10 years, however, we have learned most of what we know about Kv4 channels and their auxiliary β-subunits in brain, heart and smooth muscle. It is now generally accepted that the neuronal Kv4 channel complex is composed of at least three distinct classes of subunits: the pore-forming α-subunit Shal/Kv4, and two auxiliary β-subunits (KChIPs and DPLPs). These auxiliary β-subunits are integral components of the native complex, and therefore, their functional effects in heterologous expression systems suggest a constitutive overhaul or remodeling of the channel rather than modulation (as it would be with other signaling proteins). Accordingly, ternary Kv4 channels including these subunits have electrophysiological features that for the first time truly begin to resemble those of native Kv4 channels that underlie the ISA [81, 87]. Therefore, only by investigating the mechanism that govern the function of ternary Kv4 channel complexes [6] (Amarillo et al., J. Physiol., in press), we will begin to understand how they work, how they are modulated by signaling processes (e.g., phosphorylation/dephosphorylation, arachidonic acid, NO, Zn2+, etc.), how they impact critical physiological processes, and how they could be involved in disease states. In the immediate future, we hope to learn more about the molecular mechanism of closed-state inactivation, the gating role of the T1 domain, and the specific mechanisms governing the actions of KChIPs and DPLPs. Also, we expect important advances at both ends of the biological spectrum, which may reveal more about the atomic structure of the Kv4 channel complex and its role in complex neuronal processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Bernardo Rudy and Henry H. Jerng for fruitful discussions, critical comments and suggestions. Our studies have been supported by a research grant from National Institutes of Health (R01 NS032337-12 to M.C.) and, in part, by a Research Enhancement Award (REA to M.C.) from Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. PA. K.D., T.R., and G.W. were supported by a training grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 AA007463-22).

Footnotes

Special issue article in honor of Dr. Ricardo Tapia.

Contributor Information

Manuel Covarrubias, Department of Pathology, Anatomy and Cell Biology, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, 1020 Locust Street, JAH 245, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA.

Aditya Bhattacharji, Department of Pathology, Anatomy and Cell Biology, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, 1020 Locust Street, JAH 245, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA.

Jose A. De Santiago-Castillo, Department of Pathology, Anatomy and Cell Biology, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, 1020 Locust Street, JAH 245, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA

Kevin Dougherty, Department of Pathology, Anatomy and Cell Biology, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, 1020 Locust Street, JAH 245, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA.

Yuri A. Kaulin, Department of Pathology, Anatomy and Cell Biology, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, 1020 Locust Street, JAH 245, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA

Thanawath Ratanadilok Na-Phuket, Department of Pathology, Anatomy and Cell Biology, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, 1020 Locust Street, JAH 245, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA.

Guangyu Wang, Department of Pathology, Anatomy and Cell Biology, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, 1020 Locust Street, JAH 245, Philadelphia, PA 19107, USA.

References

- 1.Amberg GC, Koh SD, Imaizumi Y, Ohya S, Sanders KM. A-type potassium currents in smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C583–C595. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00301.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An WF, Bowlby MR, Betty M, Cao J, Ling HP, Mendoza G, Hinson JW, Mattsson KI, Strassle BW, Trimmer JS, Rhodes KJ. Modulation of A-type potassium channels by a family of calcium sensors. Nature. 2000;403:553–556. doi: 10.1038/35000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bahring R, Boland LM, Varghese A, Gebauer M, Pongs O. Kinetic analysis of open- and closed-state inactivation transitions in human Kv4.2 A-type potassium channels. J Physiol. 2001;535:65–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00065.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahring R, Dannenberg J, Peters HC, Leicher T, Pongs O, Isbrandt D. Conserved Kv4 N-terminal domain critical for effects of Kv channel-interacting protein 2.2 on channel expression and gating. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23888–23894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin TJ, Tsaur ML, Lopez GA, Jan YN, Jan LY. Characterization of a mammalian cDNA for an inactivating voltage-sensitive K+ channel. Neuron. 1991;7:471–483. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90299-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barghaan J, Tozakidou M, Ehmke H, Bahring R. Role of N-terminal domain and accessory subunits in controlling deactivation-inactivation coupling of Kv4.2 channels. Biophys J. 2007 doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.111344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barghaan J, Tozakidou M, Ehmke H, Bahring R. Role of N-terminal domain and accessory subunits in controlling deactivation–inactivation coupling of Kv4.2 channels. Biophys J. 2008;94:1276–1294. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.111344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baro DJ, Coniglio LM, Cole CL, Rodriguez HE, Lubell JK, Kim MT, Harris-Warrick RM. Lobster shal: comparison with Drosophila shal and native potassium currents in identified neurons. J Neurosci. 1996;16:1689–1701. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-05-01689.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beck EJ, Bowlby M, An WF, Rhodes KJ, Covarrubias M. Remodelling inactivation gating of Kv4 channels by KChIP-1, a small-molecular-weight calcium binding protein. J Physiol. 2002;538:691–706. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beck EJ, Covarrubias M. Kv4 channels exhibit modulation of closed-state inactivation in inside-out patches. Biophys J. 2001;81:867–883. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75747-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekkers JM. Distribution and activation of voltage-gated potassium channels in cell-attached and outside-out patches from large layer 5 cortical pyramidal neurons of the rat. J Physiol. 2000;525(Pt 3):611–620. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-2-00611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernard C, Anderson A, Becker A, Poolos NP, Beck H, Johnston D. Acquired dendritic channelopathy in temporal lobe epilepsy. Science. 2004;305:532–535. doi: 10.1126/science.1097065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bezanilla F. The voltage-sensor structure in a voltage-gated channel. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:166–168. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Birnbaum SG, Varga AW, Yuan LL, Anderson AE, Sweatt JD, Schrader LA. Structure and function of Kv4-family transient potassium channels. Physiol Rev. 2004;84:803–833. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00039.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bixby KA, Nanao MH, Shen NV, Kreusch A, Bellamy H, Pfaffinger PJ, Choe S. Zn2+-binding and molecular determinants of tetramerization in voltage-gated K+ channels. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:38–43. doi: 10.1038/4911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boland LM, Jiang M, Lee SY, Fahrenkrug SC, Harnett MT, O’Grady SM. Functional properties of a brain-specific NH2-terminally spliced modulator of Kv4 channels. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285:C161–C170. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00416.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bossy-Wetzel E, Talantova MV, Lee WD, Scholzke MN, Harrop A, Mathews E, Gotz T, Han J, Ellisman MH, Perkins GA, Lipton SA. Crosstalk between nitric oxide and zinc pathways to neuronal cell death involving mitochondrial dysfunction and p38-activated K+ channels. Neuron. 2004;41:351–365. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burgoyne RD. Neuronal calcium sensor proteins: generating diversity in neuronal Ca2+ signalling. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:182–193. doi: 10.1038/nrn2093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burgoyne RD, O’Callaghan DW, Hasdemir B, Haynes LP, Tepikin AV. Neuronal Ca2+-sensor proteins: multitalented regulators of neuronal function. Trends Neurosci. 2004;27:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cai X, Liang CW, Muralidharan S, Kao JP, Tang CM, Thompson SM. Unique roles of SK and Kv4.2 potassium channels in dendritic integration. Neuron. 2004;44:351–364. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Callsen B, Isbrandt D, Sauter K, Hartmann LS, Pongs O, Bahring R. Contribution of N- and C-terminal channel domains to Kv channel interacting proteins in a mammalian cell line. J Physiol. 2005;568:397–412. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.094359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chabala LD, Bakry N, Covarrubias M. Low molecular weight poly(A)+ mRNA species encode factors that modulate gating of a non-Shaker A-type K+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 1993;102:713–728. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.4.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen CP, Lee L, Chang LS. Effects of metal-binding properties of human Kv channel-interacting proteins on their molecular structure and binding with Kv4.2 channel. Protein J. 2006;25:345–351. doi: 10.1007/s10930-006-9020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Johnston D. Properties of single voltage-dependent K+ channels in dendrites of CA1 pyramidal neurones of rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2004;559:187–203. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.068114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen X, Yuan LL, Zhao C, Birnbaum SG, Frick A, Jung WE, Schwarz TL, Sweatt JD, Johnston D. Deletion of Kv4.2 gene eliminates dendritic A-type K+ current and enhances induction of long-term potentiation in hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:12143–12151. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2667-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi KL, Aldrich RW, Yellen G. Tetraethylammonium blockade distinguishes two inactivation mechanisms in voltage-activated K+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5092–5095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christie JM, Westbrook GL. Regulation of backpropa-gating action potentials in mitral cell lateral dendrites by A-type potassium currents. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2466–2472. doi: 10.1152/jn.00997.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Connor JA, Stevens CF. Voltage clamp studies of a transient outward membrane current in gastropod neural somata. J Physiol. 1971;213:21–30. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordero-Morales JF, Cuello LG, Zhao Y, Jogini V, Cortes DM, Roux B, Perozo E. Molecular determinants of gating at the potassium-channel selectivity filter. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:311–318. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cordero-Morales JF, Jogini V, Lewis A, Vasquez V, Cortes DM, Roux B, Perozo E. Molecular driving forces determining potassium channel slow inactivation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1062–1069. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Covarrubias M, Wei AA, Salkoff L. Shaker, Shal, Shab, and Shaw express independent K+ current systems. Neuron. 1991;7:763–773. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cushman SJ, Nanao MH, Jahng AW, DeRubeis D, Choe S, Pfaffinger PJ. Voltage dependent activation of potassium channels is coupled to T1 domain structure. Nat Struct Biol. 2000;7:403–407. doi: 10.1038/75185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dougherty K, Covarrubias M. A dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-like protein remodels gating charge dynamics in Kv4.2 channels. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:745–753. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eghbali M, Olcese R, Zarei MM, Toro L, Stefani E. External pore collapse as an inactivation mechanism for Kv4.3 K+ channels. J Membr Biol. 2002;188:73–86. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fawcett GL, Santi CM, Butler A, Harris T, Covarrubias M, Salkoff L. Mutant analysis of the Shal (Kv4) voltage-gated fast transient K+ channel in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30725–30735. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605814200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gebauer M, Isbrandt D, Sauter K, Callsen B, Nolting A, Pongs O, Bahring R. N-type inactivation features of Kv4.2 channel gating. Biophys J. 2004;86:210–223. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74097-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu C, Jan YN, Jan LY. A conserved domain in axonal targeting of Kv1 (Shaker) voltage-gated potassium channels. Science. 2003;301:646–649. doi: 10.1126/science.1086998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gulbis JM, Zhou M, Mann S, MacKinnon R. Structure of the cytoplasmic beta subunit-T1 assembly of voltage-dependent K+ channels. Science. 2000;289:123–127. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hagiwara S, Kusano K, Saito N. Membrane changes of onchidium nerve cell in potassium-rich media. J Physiol. 1961;155:470–489. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1961.sp006640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanlon MR, Wallace BA. Structure and function of voltage-dependent ion channel regulatory beta subunits. Biochemistry. 2002;41:2886–2894. doi: 10.1021/bi0119565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hille B. Ionic channels of excitable membranes. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, Mass: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hoffman DA, Magee JC, Colbert CM, Johnston D. K+ channel regulation of signal propagation in dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons [see comments] Nature. 1997;387:869–875. doi: 10.1038/43119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holmqvist MH, Cao J, Hernandez-Pineda R, Jacobson MD, Carroll KI, Sung MA, Betty M, Ge P, Gilbride KJ, Brown ME, Jurman ME, Lawson D, Silos-Santiago I, Xie Y, Covarrubias M, Rhodes KJ, Distefano PS, An WF. Elimination of fast inactivation in Kv4 A-type potassium channels by an auxiliary subunit domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:1035–1040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022509299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoshi T, Zagotta WN, Aldrich RW. Biophysical and molecular mechanisms of Shaker potassium channel inactivation. Science. 1990;250:533–538. doi: 10.1126/science.2122519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoshi T, Zagotta WN, Aldrich RW. Two types of inactivation in Shaker K+ channels: effects of alterations in the carboxy-terminal region. Neuron. 1991;7:547–556. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(91)90367-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu HJ, Carrasquillo Y, Karim F, Jung WE, Nerbonne JM, Schwarz TL, Gereau RW. The kv4.2 potassium channel subunit is required for pain plasticity. Neuron. 2006;50:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ilbert M, Graf PC, Jakob U. Zinc center as redox switch–new function for an old motif. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:835–846. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jahng AW, Strang C, Kaiser D, Pollard T, Pfaffinger P, Choe S. Zinc mediates assembly of the T1 domain of the voltage-gated K+ channel 4.2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:47885–47890. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208416200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jan LY, Jan YN. Cloned potassium channels from eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1997;20:91–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.20.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jegla T, Salkoff L. A novel subunit for Shal K+ channels radically alters activation and inactivation. J Neurosci. 1997;17:32–44. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-01-00032.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jerng HH, Covarrubias M. K+ channel inactivation mediated by the concerted action of the cytoplasmic N- and C-terminal domains. Biophys J. 1997;72:163–174. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78655-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jerng HH, Kunjilwar K, Pfaffinger PJ. Multiprotein assembly of Kv4.2, KChIP3 and DPP10 produces ternary channel complexes with ISA-like properties. J Physiol. 2005;568:767–788. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.087858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jerng HH, Lauver AD, Pfaffinger PJ. DPP10 splice variants are localized in distinct neuronal populations and act to differentially regulate the inactivation properties of Kv4-based ion channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;35:604–624. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jerng HH, Pfaffinger PJ, Covarrubias M. Molecular physiology and modulation of somatodendritic A-type potassium channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27:343–369. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jerng HH, Qian Y, Pfaffinger PJ. Modulation of Kv4.2 channel expression and gating by dipeptidyl peptidase 10 (DPP10) Biophys J. 2004;87:2380–2396. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.042358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jerng HH, Shahidullah M, Covarrubias M. Inactivation gating of Kv4 potassium channels: molecular interactions involving the inner vestibule of the pore. J Gen Physiol. 1999;113:641–660. doi: 10.1085/jgp.113.5.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnston D, Christie BR, Frick A, Gray R, Hoffman DA, Schexnayder LK, Watanabe S, Yuan LL. Active dendrites, potassium channels and synaptic plasticity. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2003;358:667–674. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2002.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnston D, Hoffman DA, Magee JC, Poolos NP, Watanabe S, Colbert CM, Migliore M. Dendritic potassium channels in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Physiol. 2000;525(Pt 1):75–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.00075.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaulin Y, Santiago-Castillo JA, Rocha C, Covarrubias M. Mechanism of the modulation of Kv4:KChIP-1 channels by external K+ Biophys J. 2007;94:1241–1251. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim J, Jung SC, Clemens AM, Petralia RS, Hoffman DA. Regulation of dendritic excitability by activity-dependent trafficking of the A-type K+ channel subunit Kv4.2 in hippocampal neurons. Neuron. 2007;54:933–947. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim J, Wei DS, Hoffman DA. Kv4 potassium channel subunits control action potential repolarization and frequency-dependent broadening in rat hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurones. J Physiol. 2005;569:41–57. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.095042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kin Y, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y. Biosynthesis and characterization of the brain-specific membrane protein DPPX, a dipeptidyl peptidase IV-related protein. J Biochem (Tokyo) 2001;129:289–295. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kirichok YV, Nikolaev AV, Krishtal OA. [K+]out accelerates inactivation of Shal-channels responsible for A-current in rat CA1 neurons. Neuroreport. 1998;9:625–629. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199803090-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klee R, Ficker E, Heinemann U. Comparison of voltage-dependent potassium currents in rat pyramidal neurons acutely isolated from hippocampal regions CA1 and CA3. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:1982–1995. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.5.1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kobertz WR, Williams C, Miller C. Hanging gondola structure of the T1 domain in a voltage-gated K+ channel. Biochemistry. 2000;39:10347–10352. doi: 10.1021/bi001292j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kreusch A, Pfaffinger PJ, Stevens CF, Choe S. Crystal structure of the tetramerization domain of the Shaker potassium channel. Nature. 1998;392:945–948. doi: 10.1038/31978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lai HC, Jan LY. The distribution and targeting of neuronal voltage-gated ion channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:548–562. doi: 10.1038/nrn1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lauver A, Yuan LL, Jeromin A, Nadin BM, Rodriguez JJ, Davies HA, Stewart MG, Wu GY, Pfaffinger PJ. Manipulating Kv4.2 identifies a specific component of hippocampal pyramidal neuron A-current that depends upon Kv4.2 expression. J Neurochem. 2006;99:1207–1223. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04185.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Levitan IB. Signaling protein complexes associated with neuronal ion channels. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:305–310. doi: 10.1038/nn1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Levy DI, Deutsch C. Recovery from C-type inactivation is modulated by extracellular potassium. Biophys J. 1996;70:798–805. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79619-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li M, Jan YN, Jan LY. Specification of subunit assembly by the hydrophilic amino-terminal domain of the Shaker potassium channel. Science. 1992;257:1225–1230. doi: 10.1126/science.1519059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li YV, Hough CJ, Sarvey JM. Do we need zinc to think? Sci STKE. 2003;2003:e19. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.182.pe19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lien CC, Martina M, Schultz JH, Ehmke H, Jonas P. Gating, modulation and subunit composition of voltage-gated K+ channels in dendritic inhibitory interneurones of rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2002;538:405–419. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Liss B, Franz O, Sewing S, Bruns R, Neuhoff H, Roeper J. Tuning pacemaker frequency of individual dopaminergic neurons by Kv4.3L and KChIP3.1 transcription. EMBO J. 2001;20:5715–5724. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Long SB, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Crystal structure of a mammalian voltage-dependent shaker family K+ channel. Science. 2005;309:897–902. doi: 10.1126/science.1116269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Long SB, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Voltage sensor of Kv1.2: structural basis of electromechanical coupling. Science. 2005;309:903–908. doi: 10.1126/science.1116270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Long SB, Tao X, Campbell EB, MacKinnon R. Atomic structure of a voltage-dependent K+ channel in a lipid membrane-like environment. Nature. 2007;450:376–382. doi: 10.1038/nature06265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lopez-Barneo J, Hoshi T, Heinemann SH, Aldrich RW. Effects of external cations and mutations in the pore region on C-type inactivation of Shaker potassium channels. Receptors Channels. 1993;1:61–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.MacKinnon R. Potassium channels and the atomic basis of selective ion conduction (Nobel lecture) Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:4265–4277. doi: 10.1002/anie.200400662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Malin SA, Nerbonne JM. Elimination of the fast transient in superior cervical ganglion neurons with expression of Kv4.2W362F: molecular dissection of IA. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5191–5199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-14-05191.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Malin SA, Nerbonne JM. Molecular heterogeneity of the voltage-gated fast transient outward K+ current, I(Af), in mammalian neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8004–8014. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-20-08004.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Maret W. Zinc coordination environments in proteins as redox sensors and signal transducers. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1419–1441. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Martina M, Schultz JH, Ehmke H, Monyer H, Jonas P. Functional and molecular differences between voltage-gated K+ channels of fast-spiking interneurons and pyramidal neurons of rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1998;18:8111–8125. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-20-08111.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Migliore M, Hoffman DA, Magee JC, Johnston D. Role of an A-type K+ conductance in the back-propagation of action potentials in the dendrites of hippocampal pyramidal neurons. J Comput Neurosci. 1999;7:5–15. doi: 10.1023/a:1008906225285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Minor DL, Lin YF, Mobley BC, Avelar A, Jan YN, Jan LY, Berger JM. The polar T1 interface is linked to conformational changes that open the voltage-gated potassium channel. Cell. 2000;102:657–670. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00088-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nadal MS, Amarillo Y, Vega-Saenz dM, Rudy B. Differential characterization of three alternative spliced isoforms of DPPX. Brain Res. 2006;1094:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.03.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Amarillo Y, de Miera EV, Ma Y, Mo W, Goldberg EM, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y, Neubert TA, Rudy B. The CD26-related dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-like protein DPPX is a critical component of neuronal A-type K+ channels. Neuron. 2003;37:449–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Nanao MH, Zhou W, Pfaffinger PJ, Choe S. Determining the basis of channel-tetramerization specificity by X-ray crystallography and a sequence-comparison algorithm: family values (FamVal) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8670–8675. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432840100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Neher E. Two fast transient current components during voltage clamp on snail neurons. J Gen Physiol. 1971;58:36–53. doi: 10.1085/jgp.58.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nerbonne JM. Molecular basis of functional voltage-gated K+ channel diversity in the mammalian myocardium. J Physiol. 2000;525(Pt 2):285–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00285.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ogielska EM, Zagotta WN, Hoshi T, Heinemann SH, Haab J, Aldrich RW. Cooperative subunit interactions in C-type inactivation of K+ channels. Biophys J. 1995;69:2449–2457. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80114-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Pak MD, Baker K, Covarrubias M, Butler A, Ratcliffe A, Salkoff L. mShal, a subfamily of A-type K+ channel cloned from mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4386–4390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Panyi G, Deutsch C. Cross talk between activation and slow inactivation gates of Shaker potassium channels. J Gen Physiol. 2006;128:547–559. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Panyi G, Sheng Z, Deutsch C. C-type inactivation of a voltage-gated K+ channel occurs by a cooperative mechanism. Biophys J. 1995;69:896–903. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79963-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Patel SP, Campbell DL. Transient outward potassium current, ‘Ito’, phenotypes in the mammalian left ventricle: underlying molecular, cellular and biophysical mechanisms. J Physiol. 2005;569:7–39. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.086223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Patel SP, Campbell DL, Strauss HC. Elucidating KChIP effects on Kv4.3 inactivation and recovery kinetics with a minimal KChIP2 isoform. J Physiol. 2002;545:5–11. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.031856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pathak MM, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Agarwal G, Roux B, Barth P, Kohout S, Tombola F, Isacoff EY. Closing in on the resting state of the shaker K+ channel. Neuron. 2007;56:124–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Pioletti M, Findeisen F, Hura GL, Minor DL., Jr Three-dimensional structure of the KChIP1-Kv4.3 T1 complex reveals a cross-shaped octamer. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:987–995. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pongs O, Leicher T, Berger M, Roeper J, Bahring R, Wray D, Giese KP, Silva AJ, Storm JF. Functional and molecular aspects of voltage-gated K+ channel beta subunits. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;868:344–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb11296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ren X, Hayashi Y, Yoshimura N, Takimoto K. Trans-membrane interaction mediates complex formation between peptidase homologues and Kv4 channels. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;29:320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ren X, Shand SH, Takimoto K. Effective association of Kv channel-interacting proteins with Kv4 channel is mediated with their unique core peptide. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43564–43570. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302337200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ridnour LA, Thomas DD, Mancardi D, Espey MG, Miranda KM, Paolocci N, Feelisch M, Fukuto J, Wink DA. The chemistry of nitrosative stress induced by nitric oxide and reactive nitrogen oxide species. Putting perspective on stressful biological situations. Biol Chem. 2004;385:1–10. doi: 10.1515/BC.2004.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rivera JF, Ahmad S, Quick MW, Liman ER, Arnold DB. An evolutionarily conserved dileucine motif in Shal K+ channels mediates dendritic targeting. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:243–250. doi: 10.1038/nn1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rivera JF, Chu PJ, Arnold DB. The T1 domain of Kv1.3 mediates intracellular targeting to axons. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;22:1853–1862. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04384.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Robinson JM, Deutsch C. Coupled tertiary folding and oligomerization of the T1 domain of Kv channels. Neuron. 2005;45:223–232. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rudy B. Diversity and ubiquity of K channels. Neuroscience. 1998;25:729–749. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Salkoff L, Baker K, Butler A, Covarrubias M, Pak MD, Wei A. An essential ‘set’ of K+ channels conserved in flies, mice and humans. Trends Neurosci. 1992;15:161–166. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(92)90165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Salvador-Recatala V, Gallin WJ, Abbruzzese J, Ruben PC, Spencer AN. A potassium channel (Kv4) cloned from the heart of the tunicate Ciona intestinalis and its modulation by a KChIP subunit. J Exp Biol. 2006;209:731–747. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Scannevin RH, Wang K, Jow F, Megules J, Kopsco DC, Edris W, Carroll KC, Lu Q, Xu W, Xu Z, Katz AH, Olland S, Lin L, Taylor M, Stahl M, Malakian K, Somers W, Mosyak L, Bowlby MR, Chanda P, Rhodes KJ. Two N-terminal domains of Kv4 K+ channels regulate binding to and modulation by KChIP1. Neuron. 2004;41:587–598. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00049-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Schoppa NE, Westbrook GL. Regulation of synaptic timing in the olfactory bulb by an A-type potassium current. Nat Neurosci. 1999;2:1106–1113. doi: 10.1038/16033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Serodio P, Kentros C, Rudy B. Identification of molecular components of A-type channels activating at subthreshold potentials. J Neurophysiol. 1994;72:1516–1529. doi: 10.1152/jn.1994.72.4.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Serodio P, Vega-Saenz dM, Rudy B. Cloning of a novel component of A-type K+ channels operating at subthreshold potentials with unique expression in heart and brain. J Neurophysiol. 1996;75:2174–2179. doi: 10.1152/jn.1996.75.5.2174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sheng M, Tsaur ML, Jan YN, Jan LY. Contrasting sub-cellular localization of the Kv1.2 K+ channel subunit in different neurons of rat brain. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2408–2417. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02408.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Shibata R, Nakahira K, Shibasaki K, Wakazono Y, Imoto K, Ikenaka K. A-type K+ current mediated by the Kv4 channel regulates the generation of action potential in developing cerebellar granule cells. J Neurosci. 2000;20:4145–4155. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-11-04145.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Shin KS, Maertens C, Proenza C, Rothberg BS, Yellen G. Inactivation in HCN channels results from reclosure of the activation gate: desensitization to voltage. Neuron. 2004;41:737–744. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Skerritt MR, Campbell DL. Role of S4 positively charged residues in the regulation of Kv4.3 inactivation and recovery. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C906–C914. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00167.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Solc CK, Aldrich RW. Voltage-gated potassium channels in larval CNS neurons of Drosophila. J Neurosci. 1988;8:2556–2570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-07-02556.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Song WJ, Tkatch T, Baranauskas G, Ichinohe N, Kitai ST, Surmeier DJ. Somatodendritic depolarization-activated potassium currents in rat neostriatal cholinergic interneurons are predominantly of the A type and attributable to coexpression of Kv4.2 and Kv4.1 subunits. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3124–3137. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03124.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Strang C, Kunjilwar K, DeRubeis D, Peterson D, Pfaffinger PJ. The role of Zn2+ in Shal voltage-gated potassium channel formation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31361–31371. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304268200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Takimoto K, Ren X. KChIPs (Kv channel-interacting proteins)—a few surprises and another. J Physiol. 2002;545:3. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.033993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tkatch T, Baranauskas G, Surmeier DJ. Kv4.2 mRNA abundance and A-type K+ current amplitude are linearly related in basal ganglia and basal forebrain neurons. J Neurosci. 2000;20:579–588. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-02-00579.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tsunoda S, Salkoff L. Genetic analysis of Drosophila neurons: Shal, Shaw, and Shab encode most embryonic potassium currents. J Neurosci. 1995;15:t-54. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-03-01741.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Van Hoorick D, Raes A, Keysers W, Mayeur E, Snyders DJ. Differential modulation of Kv4 kinetics by KCHIP1 splice variants. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;24:357–366. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(03)00174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wang G, Covarrubias M. Voltage-dependent gating rearrangements in the intracellular T1–T1 interface of a K+ channel. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:391–400. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wang G, Shahidullah M, Rocha CA, Strang C, Pfaffinger PJ, Covarrubias M. Functionally active T1–T1 interfaces revealed by the accessibility of intracellular thiolate groups in Kv4 channels. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:55–69. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wang G, Strang C, Pfaffinger PJ, Covarrubias M. Zn2+-dependent redox switch in the intracellular T1–T1 interface of a Kv channel. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:13637–13647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609182200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wang H, Yan Y, Liu Q, Huang Y, Shen Y, Chen L, Chen Y, Yang Q, Hao Q, Wang K, Chai J. Structural basis for modulation of Kv4 K+ channels by auxiliary KChIP subunits. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:32–39. doi: 10.1038/nn1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Wang S, Bondarenko VE, Qu YJ, Bett GC, Morales MJ, Rasmusson RL, Strauss HC. Time- and voltage-dependent components of Kv4.3 inactivation. Biophys J. 2005;89:3026–3041. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.059378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Watanabe S, Hoffman DA, Migliore M, Johnston D. Dendritic K+ channels contribute to spike-timing dependent long-term potentiation in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:8366–8371. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122210599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wei A, Covarrubias M, Butler A, Baker K, Pak M, Salkoff L. K+ current diversity is produced by an extended gene family conserved in Drosophila and mouse. Science. 1990;248:599–603. doi: 10.1126/science.2333511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Xu J, Yu W, Jan YN, Jan LY, Li M. Assembly of voltage-gated potassium channels. Conserved hydrophilic motifs determine subfamily-specific interactions between the alpha-subunits. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:24761–24768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.42.24761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yeh JZ, Armstrong CM. Immobilisation of gating charge by a substance that simulates inactivation. Nature. 1978;273:387–389. doi: 10.1038/273387a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Yellen G. The moving parts of voltage-gated ion channels. Q Rev Biophys. 1998;31:239–295. doi: 10.1017/s0033583598003448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Zagha E, Ozaita A, Chang SY, Nadal MS, Lin U, Saganich MJ, McCormack T, Akinsanya KO, Qi SY, Rudy B. DPP10 modulates Kv4-mediated A-type potassium channels. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18853–18861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410613200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Zhou M, Morais-Cabral JH, Mann S, MacKinnon R. Potassium channel receptor site for the inactivation gate and quaternary amine inhibitors. Nature. 2001;411:657–661. doi: 10.1038/35079500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Zhou W, Qian Y, Kunjilwar K, Pfaffinger PJ, Choe S. Structural insights into the functional interaction of KChIP1 with Shal-Type K+ channels. Neuron. 2004;41:573–586. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]