Summary

Colonization of conducting airways of humans by the prokaryote Mycoplasma pneumoniae is mediated by a differentiated terminal organelle important in cytadherence, gliding motility and cell division. TopJ is a predicted J-domain co-chaperone also having domains unique to mycoplasma terminal organelle proteins and is essential for terminal organelle function, as well as stabilization of protein P24, which is required for normal initiation of terminal organelle formation. J-domains activate the ATPase of DnaK chaperones, facilitating peptide binding and proper protein folding. We performed mutational analysis of the predicted J-domain, central acidic and proline-rich (APR) domain, and C-terminal domain of TopJ and assessed the phenotypic consequences when introduced into an M. pneumoniae topJ mutant. A TopJ derivative with amino acid substitutions in the canonical J-domain histidine–proline–aspartic acid motif restored P24 levels but not normal motility, morphology or cytadherence, consistent with a J-domain co-chaperone function. In contrast, TopJ derivatives having APR or C-terminal domain deletions were less stable and failed to restore P24, but resulted in normal morphology, intermediate gliding motility and cytadherence levels exceeding that of wild-type cells. Results from immunofluorescence microscopy suggest that both the APR and C-terminal domains, but not the histidine–proline–aspartic acid motif, are critical for TopJ localization to the terminal organelle.

Introduction

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a leading cause of community-acquired atypical pneumonia with almost 18% of cases in children requiring hospitalization (Waites, 2003). Attachment to the host respiratory epithelium (cytadherence) constitutes a critical step in pathogenesis and is mediated largely by the terminal organelle. This multifunctional polar structure is a membrane-bound extension of the mycoplasma cell and defined by a central electron-dense core, with adherence-associated proteins clustered at a terminal cap (reviewed in Razin and Jacobs, 1992; Krause, 1996). The primary adhesin P1 (Hu et al., 1977) and adhesin-related P30 (Baseman et al., 1987) depend on an entourage of cytadherence-associated proteins for achieving and maintaining proper spatial distribution and functional capacity for receptor recognition. The principal cytadherence-accessory proteins, HMW1–HMW3, B, C, and P65 (Hansen et al., 1979; Krause et al., 1982; Layh-Schmitt and Herrmann, 1992; Proft et al., 1995; Jordan et al., 2001), are components of a cytoskeletal network defined by its Triton X-100 insolubility (Meng and Pfister, 1980; Gobel et al., 1981), acting as a scaffold for the insertion and stability of P1 and P30 in the membrane (Hahn et al., 1998; Layh-Schmitt and Harkenthal, 1999; Jordan et al., 2001; Willby and Krause, 2002; Krause and Balish, 2004). The partitioning of the chaperone DnaK into the Triton X-100-insoluble network (Regula et al., 2001) complexed with P1 (Layh-Schmitt et al., 2000) raised the possibility of chaperone-assisted terminal organelle assembly. Isolation of a cytadherence-deficient mutant lacking TopJ, a predicted J-domain terminal organelle co-chaperone, reinforced this model (Cloward and Krause, 2009).

Molecular chaperones promote cellular homeostasis during general maintenance and as a response to stress by enforcing accurate protein folding, assembly/disassembly/stabilization of macromolecular complexes, and translocation of proteins across membranes (Dougan et al., 2002; Hartl and Hayer-Hartl, 2002). DnaK binds and releases short hydrophobic stretches of polypeptides following J-domain stimulation of the DnaK ATPase and GrpE-induced nucleotide exchange, respectively, until the polypeptide reaches its native state (Frydman, 2001; Hartl and Hayer-Hartl, 2002). While considerable variation exists among J-domain co-chaperones, the signature motif is highly conserved. J-domains are defined by a stretch of 70–80 amino acid residues that form four helices, with a positively charged loop containing an essential histidine–proline–aspartic acid (HPD) tripeptide between helix II and III; a single point mutation or substitution here eliminates J-domain activation of the DnaK ATPase (Greene et al., 1998; Fig. 1A). Several J-domain proteins have a glycine- and phenylalanine-rich (G/F) region immediately adjacent to the J-domain that cooperates in DnaK activation, although not in all systems. Some J-domains are further defined by their capacity to bind non-native substrates, which associate with a J-domain protein’s central repeating Zn-finger domain and/or C-terminal domain (Fig. 1B), when present, by a poorly understood mechanism (Frydman et al., 1994; Szabo et al., 1996; Cheetham and Caplan, 1998; Walsh et al., 2004). The variation in J-domain proteins produced by a cell allows compartmentalization for segregation of function, unlike the ubiquitous DnaK (Cyr et al., 1994; Frydman, 2001).

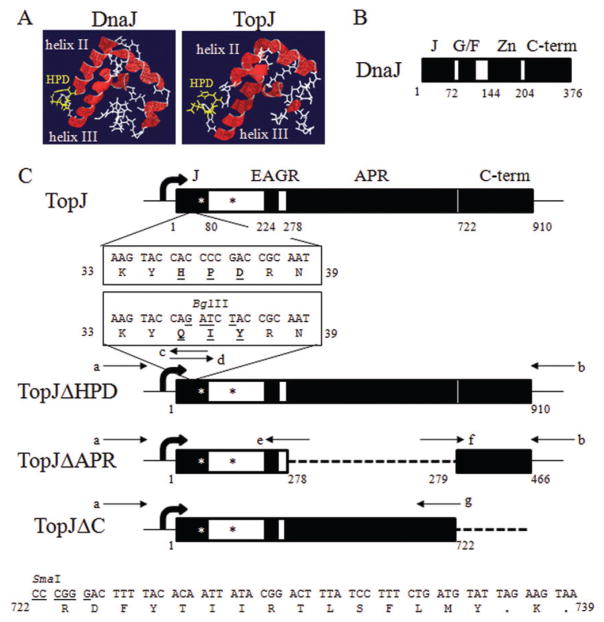

Fig. 1.

Comparison of DnaJ, TopJ and recombinant TopJ constructs.

A. Tertiary structure comparison of amino acid residues 1–80 of DnaJ (Huang et al., 1999) and TopJ using I-TASSER. Red, helices. Yellow, histidine-proline-aspartic acid (HPD) tripeptide. White, polypeptide backbone.

B. Schematic representation of DnaJ (Cheetham and Caplan, 1998). Domains identified as black boxes. J, J-domain; Zn, Zn-finger repeating motif; C-term, C-terminal domain.

C. Schematic representation of TopJ and derivatives thereof. Domains: J, J-domain; EAGR, enriched in aromatic and glycine residues. Amino acid positions corresponding to each domain indicated below the open reading frame. Deletions identified by a dotted-line. TopJΔHPD, boxed amino acid sequence identifies the native HPD tripeptide within the J-domain substituted to QIY by an engineered BglII restriction site. TopJΔC, amino acid sequence indicates downstream stop codons encoded following insertion of the topJΔC construct into the delivery vector. Block arrow, predicted promoter; small arrows, primer pairs used for each construct; asterisks, anti-TopJ epitopes (Cloward and Krause, 2009).

a. 5′-AATGTAACTGGATCCTGAACCGCTGC-3′; engineered BamHI

b. 5′-CACCATGTTAAACCCGGGGGTATAGT-3′; engineered SmaI

c. 5′-TGCCTTATTGCGGTAGATCTGGTACTTTTTGGCTAG-3′; engineered BglII

d. 5′-CTAGCCAAAAAGTACCAGATCTACCGCAATAAGGCA-3′; engineered BglII

e. 5′-CTACTAGGTTCAGTCAGATCTAGTCAAACCC-3′; engineered BglII

f. 5′-ACACAGATCTCGTACCCCAAATTTGTTTC3′; engineered BglII

g. 5′-AACTTCCCGGGTAATTGATTCCATGG-3′; engineered SmaI and NcoI

TopJ possesses the predicted signature J-domain (Fig. 1A) as well as two domains unique to only certain mycoplasmal terminal organelle proteins (Balish et al., 2001; Cloward and Krause, 2009). Proteins P200 (Proft et al., 1996; Jordan et al., 2007), P65, HMW1 and HMW3 have an acidic and proline-rich (APR) domain, while P200 and HMW1 also have an enriched in aromatic and glycine residues region; TopJ has both domains. Although the role of these domains remains unclear, a structural function and/or localization signal has been suggested (Ogle et al., 1992; Proft et al., 1995; 1996; Dirksen et al., 1996; Balish et al., 2001). In addition, the C-terminal domain of TopJ shows homology to the TopJ ortholog (MG200) in the nearest relative, Mycoplasma genitalium (Fraser et al., 1995; Pich et al., 2006), suggesting a conserved function. Therefore, derivates of topJ were constructed that resulted in the substitution of the HPD tripeptide of the J-domain with Q-I-Y (TopJΔHPD), the deletion of the APR domain (TopJΔAPR), or the deletion of the C-terminal domain (TopJΔC; Fig. 1C). Phenotypic analysis of each construct allowed prediction of the mutated or deleted domain’s function.

Loss of TopJ affects terminal organelle function resulting in cytadherence-deficient, non-motile cell chains with reduced levels of the cell division protein P24; a normal phenotype is restored by transformation with the recombinant wild-type allele (Cloward and Krause, 2009). Here, transformation of the topJ mutant with the topJΔHPD construct restored P24 to wild-type levels but had no effect on cytadherence, motility or cell morphology, suggesting that TopJ is indeed a J-domain co-chaperone likely activating DnaK for terminal organelle maturation. In contrast, the topJΔC and topJΔAPR constructs restored gliding motility, although at reduced speeds and frequencies compared with wild-type, while cytadherence actually exceeded wild-type levels. Curiously, both topJΔC and topJΔAPR failed to restore P24 and resulted in highly unstable TopJ derivatives. TopJΔHPD, but not the deletion derivatives, co-localized to the terminal organelle with P1. Furthermore, TopJΔAPR exhibited diffuse localization, unlike punctate localization for TopJΔC, suggesting that each domain contributes differently to localization and stability. The failure of TopJΔAPR or TopJΔC to restore P24 may reflect a stoichiometric or stabilizing relationship between P24 and one or both of the missing TopJ domains.

Results

Analysis of TopJ and engineered derivatives

To reinforce the sequence prediction of TopJ as a J-domain protein (Himmelreich et al., 1996), we performed tertiary structure analysis of TopJ using I-TASSER, which compares sample sequences against solved protein structures, returning predictions of topology and function with an associated TM-score (Wu et al., 2007; Zhang, 2007; 2008). Predictions having a TM-score > 0.5 are determined to be correct topological models. While the predicted structures of full-length TopJ, TopJΔAPR and TopJΔC were not statistically significant, likely due to the absence of solved mycoplasma protein structures (data not shown), tertiary structure analysis of the first 80 amino acid residues of TopJ returned a TM-score of 0.76 ± 0.10, with the closest alignments to human and Escherichia coli DnaJ J-domains. The first 80 amino acids of the prototypical J-domain chaperone DnaJ from E. coli (Ohki et al., 1986) were likewise submitted to I-TASSER as an internal assessment and yielded a TM-score of 0.63 ± 0.14, aligning with its own PDB file 1bq0A (Huang et al., 1999) as well as human DnaJ. Comparison of the TopJ and DnaJ tertiary structures identified the canonical HPD residues flanked by antiparallel helices, which are critical for DnaK activation (Fig. 1A). Therefore, these three amino acids were targeted for mutation to assess potential co-chaperone function. Additionally, deletion analysis of the mycoplasma-specific APR and conserved C-terminal domains was performed to assess potential localization or functional contributions by each (Fig. 1C).

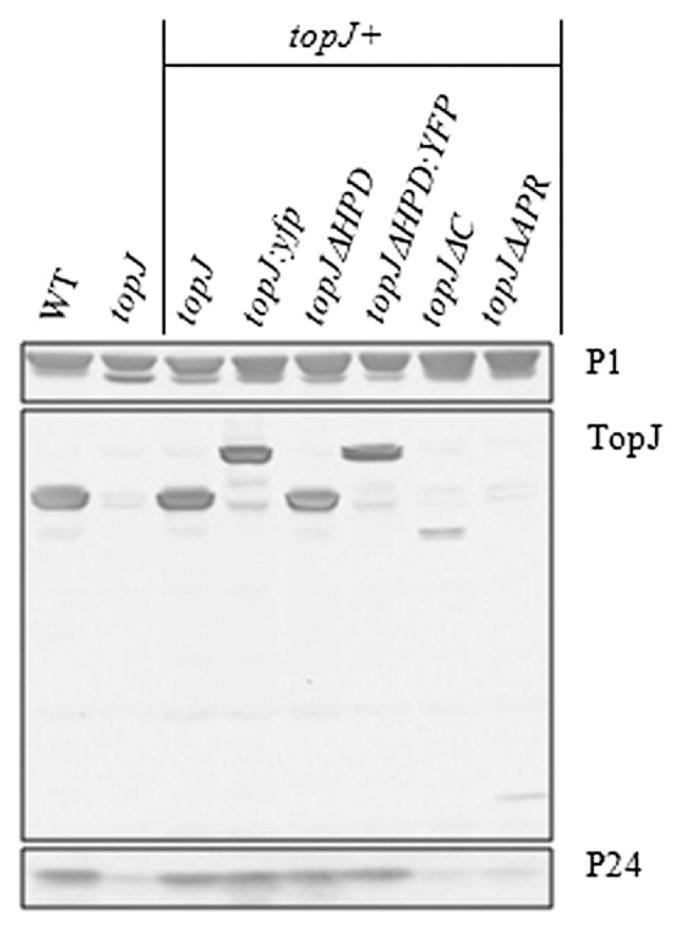

As previously reported, Tn4001 insertion in MPN119 results in loss of TopJ and reduced expression of the downstream MPN120 product GrpE, likely a polar effect partially overcome by limited transcription from the outward-reading promoter of IS256 (Byrne et al., 1989; Cloward and Krause, 2009). Furthermore, the level of the MPN312 product P24, a cell division-associated protein, is reduced fivefold, although TopJ remains at wild-type levels in the absence of P24 (data not shown). Transformation with the recombinant wild-type MPN119 allele restores TopJ and P24 to wild-type levels; however, both recombinant MPN119 and MPN120 are required for GrpE restoration (Cloward and Krause, 2009). Similar to the wild-type topJ allele, transformation with topJΔHPD here resulted in wild-type levels of both P24 and TopJΔHPD (Fig. 2). Likewise, C-terminal fusions of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) to topJ or topJΔHPD yielded stable TopJ derivatives at wild-type levels, while fully restoring P24. Removal of the C-terminus or APR domain, however, proved more destabilizing, with levels of these truncated TopJ derivative proteins reduced. Despite the presence, albeit reduced, of TopJΔC and TopJΔAPR in the respective transformants, P24 steady-state levels did not increase beyond that in the topJ mutant. For each construct, multiple transformants were evaluated and demonstrated equivalent protein levels. All other terminal organelle proteins examined remained at wild-type levels; as expected, GrpE levels remained reduced (data not shown). The topJΔHPD construct was verified by sequence analysis, confirming the HPD substitution (data not shown). Attempts to construct stable C-terminal YFP fusions to topJΔC and topJΔAPR were unsuccessful.

Fig. 2.

Western immunoblot analysis of P1, TopJ and P24 in wild-type (WT), topJ mutant and recombinant topJ derivatives. Cell lysates were subjected to 4–12% gradient SDS-PAGE and probed with the indicated antisera. Immunoblot was overdeveloped to allow visualization of all recombinant TopJ products.

To examine further the possible stoichiometric relationship between TopJ and P24, the predicted topJ promoter was replaced for topJΔC and topJΔAPR with the strong constitutive promoter for elongation factor Tu [(tuf), Weiner et al., 2003], and sequenced for accuracy prior to transformation. Although tuf-topJΔAPR resulted in a moderate increase in the TopJ derivative compared with topJΔAPR, P24 levels remained unchanged (data not shown). Neither tuf-TopJΔC nor P24 demonstrated a change from observed levels in the tuf-topJΔC transformant strain (data not shown). While these data suggest that the APR domain and/or the C-terminus of TopJ are required for P24 stability, a stoichiometric relationship cannot be excluded.

The influence of TopJ domains on terminal organelle function

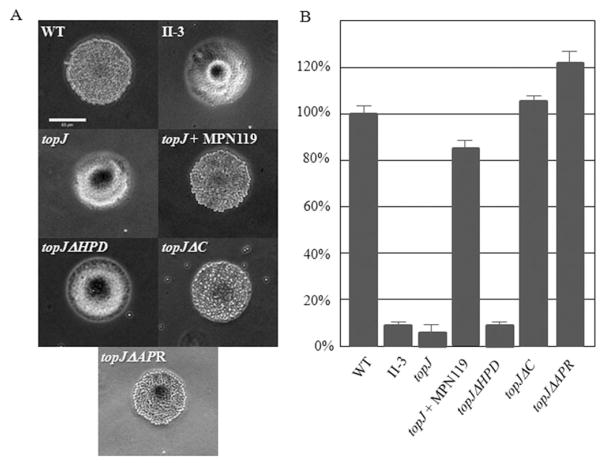

The topJ mutant was originally identified based on its failure to attach to plastic, typically indicative of a cytadherence deficiency. Transformation with the recombinant wild-type topJ allele restores cytadherence but not to fully wild-type levels (Cloward and Krause, 2009). Here, topJ mutant derivatives encoding the constructs topJΔC or topJΔAPR, but not topJΔHPD, adhered to plastic (data not shown). Furthermore, only transformant populations expressing TopJ derivatives with a wild-type J-domain were HA+ (Fig. 3A). When assessed quantitatively, the recombinant topJ allele restored HA but not to wild-type levels, as seen previously (Fig. 3B), while the topJΔHPD mutant exhibited a significant defect in HA, mirroring the topJ mutant and negative control. Curiously, both topJΔC and topJΔAPR transformants exceeded wild-type in attachment ability (Student’s t-test; P ≤ 0.01) despite a lower steady-state level of each derivative compared with that with the wild-type recombinant allele; multiple transformant strains were examined and exhibited comparable results. P24− HA was consistently at wild-type levels (data not shown). Taken together, these data suggest that a functional J-domain is required for achieving cytadherence competence.

Fig. 3.

HA analysis of wild-type (WT), topJ mutant and recombinant topJ derivatives.

A. Qualitative assessment of HA by colonies of the indicated strains. II-3, negative control. Bar; 65 μm.

B. Quantitation of adherence to erythrocytes by the indicated strains, normalized to wild-type. II-3, negative control. Error bars, standard deviation; P ≤ 0.01.

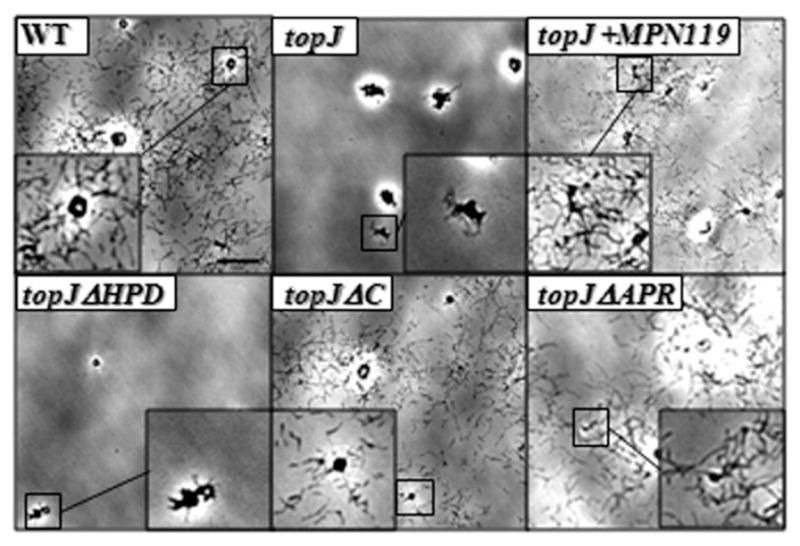

Altered satellite growth correlates well with defects in gliding motility (Hasselbring et al., 2005). At 72 h post-inoculation, both wild-type M. pneumoniae and the topJ mutant with the recombinant wild-type allele exhibited a typical satellite expansion and subsequent formation of microcolonies. In contrast, both the topJ and topJΔHPD mutants exhibited similar satellite and growth defects, forming colonies with defined centres and branched, erratic cell elongation at the periphery (Fig. 4). The topJΔC and topJΔAPR cells, however, exhibited moderate satellite growth defects, with increased spacing between colonies and the formation of cell chains respectively. A quantitative assessment of gliding motility was performed by microcinematography. No gliding was observed for either the topJ mutant, as expected, or topJΔHPD derivative (Table 1). Gliding frequencies and average speeds of topJΔC cells were moderately reduced at 66% and 60% of wild-type respectively; topJΔAPR cells exhibited a more severe gliding defect with gliding frequencies and average speed at only 22% and 32% of wild-type respectively.

Fig. 4.

Satellite growth by wild-type (WT), topJ mutant and recombinant topJ derivatives. Mycoplasmas were grown on poly-L-lysine-coated glass for 72 h in SP4 medium with 3% gelatin. Bar, 15 μm. Inset, magnification of the boxed area.

Table 1.

Comparison of gliding motility in wild-type M. pneumoniae, the topJ mutant and transformants with recombinant topJ derivatives.

| Cell gliding frequency (% WT) | Mean cell velocity μm/s ± SEMa (% WT) | Cell velocity range μm/s | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-type | 25.3 (100) | 0.181 ± 0.010 (100) | 0.051–0.351 |

| topJ | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| topJ + MPN119 | 24.5 (96.8) | 0.178 ± 0.008 (98.3) | 0.031–0.348 |

| topJ + topJΔHPD | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| topJ + topJΔC | 16.6 (65.6) | 0.109 ± 0.005 (60.2) | 0.041–0.191 |

| topJ + topJΔAPR | 5.5 (21.7) | 0.058 ± 0.003 (32.0) | 0.024–0.128 |

SEM, standard error of the mean.

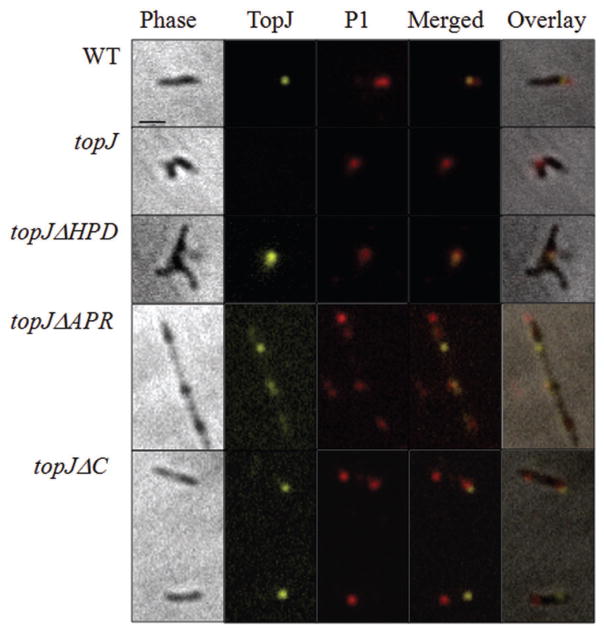

TopJ localization in topJ mutant derivatives

We employed phase-contrast/immunofluorescence microscopy to localize TopJ derivatives relative to the terminal organelle protein P1 in the topJ mutant transformants. In wild-type M. pneumoniae, P1 and TopJ are positioned at the distal and proximal ends, respectively, of the terminal organelle (Fig. 5). Here, the topJΔHPD construct co-localized with P1 but often not at a cell pole, similar to localization of several terminal organelle proteins in the topJ mutant (Cloward and Krause, 2009). In contrast, TopJΔC also formed a focus, although inconsistently paired with P1 and often localizing to an opposite cell pole from P1. TopJΔAPR often appeared punctate or diffuse throughout the cell with rare polar localization, while P1 localized to polar and non-polar sites. Therefore, both the APR and C-terminal domains are required for proper TopJ co-localization with P1 at a terminal organelle.

Fig. 5.

P1 and TopJ immunolocalization for wild-type M. pneumoniae, topJ mutant and recombinant topJ derivatives. For each row, left to right: panel 1, phase-contrast; panel 2, TopJ false-coloured yellow; panel 3, P1 false-coloured red; panel 4, merged fluorescence images; panel 5, merged phase and fluorescence images. Bar, 1 μm.

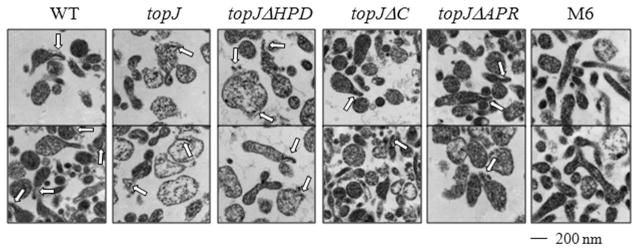

Ultrastructure and morphology of TopJ deletion derivatives

The varied immunolocalization of P1 and TopJ derivatives prompted TEM analysis of thin sections to determine the impact of TopJ on the presence and positioning of the core. While typically pleomorphic, wild-type M. pneumoniae cells sectioned longitudinally exhibited the characteristic flask shape with an electron-dense core positioned at a polar end segregated from the cell body (Fig. 6). All topJ strains formed an electron-dense core, but the cells of the topJ mutant and the topJΔHPD derivative generally appeared larger, circular or highly amorphous, and less electron-dense than wild-type cells. In contrast, topJΔC and topJΔAPR cells closely resembled the wild-type morphology.

Fig. 6.

Terminal organelle positioning in wild-type M. pneumoniae, topJ mutant and topJ derivatives. Representative micrographs. Arrows, electron-dense cores. Bar, 200 nm.

Digital image analysis of sectioned cells allowed quantitative comparisons of thin section size and relative electron density between wild-type cells, the topJ mutant and topJ derivative strains (ANOVA; P < 0.0001). The random positioning of cells in suspension resulted in thin sections through all cell planes. Therefore, total calculated area was sorted, and the top 25% of values were assumed to represent sections most likely occurring through the mid-cell and therefore allow an accurate determination of cell size (Table 2). The top 25% of wild-type cells averaged 0.142 μm2 with a maximum observed cell size of 0.291 μm2. However, the topJ mutant and topJΔHPD cells exceeded wild-type average areas by 92% and 73% respectively. As the topJ mutant, but not topJΔHPD, has reduced steady-state levels of P24, the morphological differences observed here were independent of P24 levels. Curiously, topJΔC and topJΔAPR cells exhibited near wild-type sizes, indicating a correlation with a functional J-domain. To assess whether the lack of interface with a solid surface during growth contributed to the larger observed size, the cytadherence-deficient strain M6 was examined in parallel. M6 cells averaged 0.197 μm2, larger than wild-type but over 20% smaller than both the topJ mutant and topJΔHPD cells, suggesting that the absent J-domain, and not growth in suspension, was responsible for the large cell size.

Table 2.

Cell size and density of M. pneumoniae topJ deletion derivativesa.

| WT | topJ | topJΔHPD | topJΔC | topJΔAPR | M6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cell sizeb | ||||||

| Total cells | 221 | 207 | 203 | 202 | 213 | 213 |

| Average section area | 0.072 (100%) | 0.119 (165%) | 0.107 (148%) | 0.066 (92%) | 0.087 (120%) | 0.093 (127%) |

| Median section area | 0.066 (100%) | 0.086 (131%) | 0.076 (116%) | 0.060 (91%) | 0.080 (122%) | 0.069 (105%) |

| Top 25% | 56 | 52 | 51 | 51 | 54 | 54 |

| Average section area | 0.142 (100%) | 0.273 (192%) | 0.245 (173%) | 0.118 (83%) | 0.155 (109%) | 0.197 (139%) |

| Median section area | 0.134 (100%) | 0.220 (165%) | 0.195 (146%) | 0.101 (75%) | 0.146 (109%) | 0.171 (128%) |

| Range | 0.107–0.291 | 0.152–0.692 | 0.128–0.876 | 0.078–0.247 | 0.120–0.365 | 0.119–0.437 |

| Electron densityc | ||||||

| Total population | 100% | 81% | 89% | 103% | 103% | 105% |

| Compared to largest WT cells (0.070–0.210 μm2) | 100% | 80% | 85% | 104% | 103% | 103% |

P-value ≤ 0.0001.

Section area in μm2 (% wild-type).

% of wild-type.

While measuring cell areas in thin sections, we observed significant variations in electron densities both within and between strains. Average pixel intensities per section were quantified as a measurement of relative electron density. Typically, larger and circular cell sections exhibited less relative electron density than smaller and/or more elongated sections. The topJ and topJΔHPD mutants averaged 19% and 11% less electron density, respectively, than all other strains examined (Table 2). Furthermore, the topJ and topJΔHPD mutants appeared more fragile with apparent cell content leakage, identified as fibrous strands extending outward from membrane disruptions (data not shown). Because larger cells exhibited less electron density, we examined only cell sizes falling within ±50% of the average wild-type top 25% cell size (0.070–0.210 μm2; n = 90–100 cells). Again, the topJ mutant and topJΔHPD cells demonstrated the lowest electron density (Table 2). Although all strains were harvested, fixed and processed identically, the reduced electron density of topJ and topJΔHPD mutants suggests that these strains resisted staining, lost cell contents during processing, or both. Multiple fixatives and fixation conditions were attempted with similar results for each population (data not shown). Significantly, cell sizes of fixed cells captured by phase-contrast microscopy differed by less than 10% over 80 cells (data not shown), suggesting that strain variation in thin sections was a function of increased sensitivity of some strains to sample processing. While electron-dense cores were observed in all strains, positioning of the core relative to the cell membrane differed between wild-type, the topJ mutant, and topJ transformant populations (J.M. Cloward and D.C. Krause, in preparation).

Discussion

The terminal organelle of M. pneumoniae is a remarkably complex structure (Henderson and Jensen, 2006), the assembly of which requires precise spatial, temporal and sequential incorporation of diverse structural elements (Krause and Balish, 2004). Elucidating the maturation and regulation of this complex, multifunctional structure in a genomically limited organism is critical for understanding its basic cell biology and identifying potential targets for new and more effective therapeutics. The identification of the chaperone DnaK complexed with the terminal organelle protein P1 (Layh-Schmitt et al., 2000) and the requirement of the putative J-domain co-chaperone TopJ for terminal organelle function (Cloward and Krause, 2009) suggest that terminal organelle assembly is a chaperone-assisted process. The current study establishes definitively that TopJ is a J-domain protein and examines the role of the terminal organelle-associated APR and C-terminal domains in TopJ function.

Although J-domain proteins have been extensively studied, only the J-domain itself is well-characterized as the DnaK ATPase activator, enhancing activity by up to 50-fold (Liberek et al., 1991), with accessory domains postulated to participate in DnaK activation, substrate binding or cellular compartmentalization (Cyr et al., 1994; Frydman, 2001; Walsh et al., 2004). The prototypical J-domain chaperone DnaJ has four major domains: an N-terminal J-domain, a G/F domain, a repeating Zn-finger motif and a conserved C-terminal domain (Frydman et al., 1994; Szabo et al., 1996; Cheetham and Caplan, 1998). Of the M. pneumoniae genes-encoding J-domain proteins (MPN002, MPN021 and topJ), MPN021 encodes the likely DnaJ ortholog (Himmelreich et al., 1996), raising questions regarding the purpose of the additional DnaJ-like M. pneumoniae J-domain proteins and the functional significance, if any, of the accessory domains. Therefore, domain deletion analysis of TopJ was employed focusing on: (i) HPD tripeptide substitution in the J-domain, which should prevent DnaK stimulation (Greene et al., 1998), (ii) removal of the APR domain, unique to certain mycoplasmal terminal organelle proteins (Proft et al., 1995; Balish et al., 2001) and (iii) removal of the undefined C-terminal domain, which harbours all four of the protein’s cysteine residues. All three domains are conserved in the related MG200 of M. genitalium and MGA1228 of Mycoplasma gallisepticum, suggesting a conserved function (Fraser et al., 1995; Papazisi et al., 2003). Whether the enriched in aromatic and glycine residues box is homologous to the DnaJ G/F domain or has a unique function specific to terminal organelle proteins is unknown. However, the G/F domain typically complements J-domain function (Szabo et al., 1996) and therefore was not included as a supplement to J-domain manipulation in this study.

The HPD substitution derivative topJΔHPD mirrored the topJ mutant in virtually every phenotypic assessment. While we cannot rule out the possibility that HPD substitution to QIY indirectly impacted TopJ function, it appears that TopJ is indeed a J-domain co-chaperone, with the canonical HPD residues essential for activation of DnaK ATPase in terminal organelle maturation. However, topJΔHPD restoration of P24 suggests a functional significance to TopJ beyond DnaK activation. P24 is a cytoskeletal protein that, like TopJ, localizes to the base of the terminal organelle (Hasselbring and Krause, 2007a; Cloward and Krause, 2009). Prior to cell division, a new terminal organelle forms adjacent to an existing structure (Seto et al., 2001; Hasselbring et al., 2006), but the spatial and temporal patterns of new terminal organelle formation are altered in the absence of P24 (Hasselbring and Krause, 2007a). Therefore, the requirement for TopJ to stabilize P24 suggests a role in cell division that is independent of its co-chaperone function.

Transformation of topJ with topJΔAPR or topJΔC resulted in low levels of the corresponding TopJ derivative but failed to restore P24 to wild-type levels, perhaps a function of improper stoichiometry, absence of critical binding domains, or both. Nevertheless, transformation of topJ with topJΔC otherwise restored a near-wild-type phenotype except for mild differences in cell morphology and cell growth. Curiously, haemadsorption exceeded that of wild-type, while gliding velocity was only partially restored. Transformation of topJ with topJΔAPR led to a similar but more extreme pattern, with haemadsorption even higher and gliding speeds lower. This inverse correlation between HA and gliding velocity suggests a relationship where enhanced attachment impairs gliding. While the underlying role of TopJ and DnaK remains unclear, the differences in P1 localization between topJΔAPR and topJΔC suggest that the phenotype may be multifactorial, reflecting fewer copies of each derivative to activate DnaK, aberrant localization, and perhaps a loss in efficient substrate binding in the absence of the APR or C-terminal domain (Liberek et al., 1991).

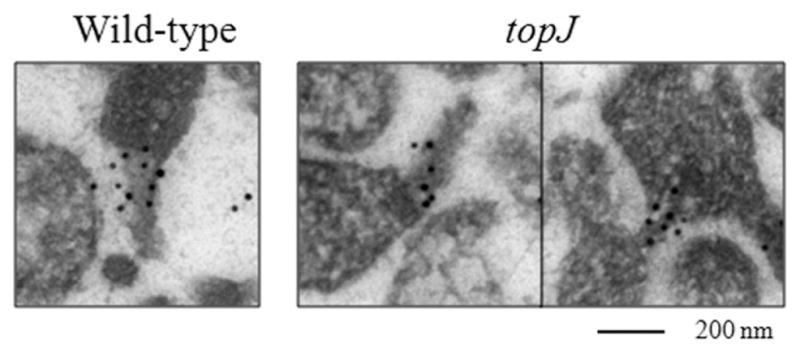

To assess whether P1 requires TopJ to localize to a terminal organelle, we employed immunoelectron microscopy and observed clear co-localization of proteins HMW1 and P1 to the electron-dense core region in wild-type and topJ mutant cells in thin section (Fig. 7). HMW1 and P1 are thought to appear early and late in terminal organelle assembly, respectively (Krause and Balish, 2001), and thus serve as a good indicator of terminal organelle assembly status. Their co-localization to the electron-dense core region whether cores were fully or partially extended, suggest normal incorporation despite defective core placement (Fig. 7 and J.M. Cloward and D.C. Krause, in preparation).

Fig. 7.

Terminal organelle assembly in wild-type M. pneumoniae and the topJ mutant. Representative immunoelectron micrographs of wild-type and topJ mutant cells in thin section co-localizing HMW1 (10 nm gold particle) and P1 (18 nm gold particle) in the region of the electron-dense core. Bar, 200 nm.

It seems noteworthy that topJΔAPR transformants formed chains. This morphology does not appear to be a function of enhanced cytadherence, reduced gliding parameters or absence of P24 alone, as mutants II-3 plus P30-YFP, II-7 and P24− exhibit these phenotypes, respectively, but do not typically form chains (Romero-Arroyo et al., 1999; Hasselbring et al., 2005; Hasselbring and Krause, 2007a). Rather, topJΔAPR transformants appear to have a unique cell division defect that is linked to terminal organelle functional development. At any given time only approximately 25% of unsynchronized cells in a wild-type population initiate binding to erythrocytes, suggesting that cytadherence is cell-cycle dependent. Furthermore, time-lapse digital imaging of growing cultures reveals the dynamic coordination of terminal organelle function in adherence, gliding and cell division (Hasselbring et al., 2006). The distinct phenotypes observed with the deletion derivatives of this terminal organelle co-chaperone underscore the adherence–gliding–cell division interrelationship, for which TopJ and P24 may begin to provide a molecular basis. However, both P41, which is required for P24 positioning (Hasselbring and Krause, 2007b), and P200 co-localize with P24 and TopJ (Kenri et al., 2004; Jordan et al., 2007) and should be considered as potential contributing partners.

The recombinant wild-type topJ allele restores haemadsorption to 75–85% of wild-type (Cloward and Krause, 2009; this study). Several explanations for the incomplete recovery in cytadherence were considered previously, including reduced fitness due to the presence of two antibiotic resistance cassettes. However, here the topJΔC and topJΔAPR transformants likewise had two antibiotic cassettes and yet exhibited haemadsorption levels exceeding that of wild-type, despite the low levels of the TopJ derivative in each. At least two explanations might account for this outcome. First, elevated cytadherence might be a function of a disjunction in cell division, as noted above. Alternatively, or in addition, M. pneumoniae may be sensitive to variations in TopJ availability and require tight regulation, perhaps involving the APR and/or C-terminal domains. If J-domain activity is controlled by substrate recognition, identifying the associated binding partners is critical for furthering our understanding of terminal organelle assembly. Perhaps significantly, the additional J-domain proteins MPN002 and MPN021 likely cannot substitute for an absent TopJ J-domain, suggesting a level of specificity within this highly conserved region similar to that of other J-domain proteins (Sullivan et al., 2000; Hennessy et al., 2005).

Experimental procedures

Strains and growth conditions

Wild-type M. pneumoniae strain M129-B18 (Lipman and Clyde, 1969), mutant II-3 (Krause et al., 1982), mutant M6 (Layh-Schmitt et al., 1995), mutant P24− (Hasselbring and Krause, 2007b), the topJ mutant (Cloward and Krause, 2009) and topJ derivative transformants (this study) were grown in tissue culture flasks with SP4 medium (Tully et al., 1977) at 37°C until mid-log phase. Gentamicin (18 μg ml−1) was included for the topJ mutant; gentamicin and chloramphenicol (24 μg ml−1) were included for P24− and the topJ derivatives and fluorescent-protein fusion constructs.

Construction and analysis of topJ deletion derivatives

The topJ derivatives were constructed using the PCR primers listed in legend of Fig. 1 and subcloned into vector pCRII® (Invitrogen) following guidelines provided with the TOPO TA Cloning Dual Promoter Kit (Invitrogen). Clones were sequenced for accuracy, excised using BamHI- and SmaI-engineered restriction sites, and cloned into a Tn4001cat delivery vector conferring chloramphenicol resistance (Hahn et al., 1999) prior to transformation of topJ mutant cells by electroporation (Hedreyda et al., 1993).

Phenotype analysis

Expression of topJ transformants compared with wild-type and the topJ mutant was analysed by sodium dodecyl SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblot as described elsewhere (Hahn et al., 1996; Hasselbring et al., 2005). Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were used at the following dilutions: anti-P1, 1:1000; anti-TopJ, 1:2000; and anti-P24, 1:250. Multiple transformants were screened for each construct, each demonstrating equivalent steady-state protein levels, with representative clones included here. Attachment of M. pneumoniae to erythrocytes serves as a convenient indicator of colonization capacity (Sobeslavsky et al., 1968). Qualitative HA by M. pneumoniae colonies and quantitative HA by radiolabelled M. pneumoniae cells in suspension followed previously described procedures (Krause and Baseman, 1982) and (Krause and Baseman, 1983; Willby and Krause, 2002), respectively, except cells were cultured in SP4 medium. M. pneumoniae mutant II-3 was used as a negative control for HA. For satellite growth and motility analysis, mycoplasmas were first incubated in four-well borosilicate glass chamber slides (Nunc Nalgene) containing SP4 medium + 3% gelatin, with antibiotics as appropriate for transformant strains. Time-lapse images of colony morphology and spreading were recorded at 12 h intervals (Hasselbring et al., 2005). Cell motility assessments of average gliding velocities and frequencies were quantitated as described (Hasselbring et al., 2005), except that all strains were incubated overnight. Between 450 and 600 cells per strain were evaluated for gliding frequency, with speeds quantitated for approximately 60–80 cells per strain. M. pneumoniae samples were prepared for thin section TEM and ultrastructural analysis, and for immunofluorescence microscopy, as described (Willby and Krause, 2002) and (Cloward and Krause, 2009) respectively. Immunogold labelling of thin sections was carried out as described (Stevens and Krause, 1991) except that grids were co-labelled with mouse anti-P1 monoclonal antibodies (1:20) and rabbit anti-HMW1 polyclonal antiserum (1:100), washed as described, and co-incubated with goat anti-mouse antibodies conjugated to 18 nm colloidal gold (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and goat anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated to 10 nm colloidal gold (Amersham Biosciences).

Statistical analysis

Tertiary structure analysis of DnaJ and TopJ was performed by I-TASSER at http://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/ (Wu et al., 2007; Zhang, 2007; 2008). Models with TM-scores > 0.5 were deemed statistically significant. Each predicted model was manually rotated and coloured using Swiss-PDBViewer v4.0 (Guex and Peitsch, 1997).

Statistical significance of quantitative HA averages between wild-type, the topJ mutant, or topJ transformant strains were determined by a Student’s t-test performed online at http://www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats. P-values ≤ 0.05 were deemed significant. The obtained P-values were <0.01.

Cell size and mean pixel intensity in TEM thin sections were determined manually by measuring each cell section using the Scion Image (Scion) marquee selection tool. The cell sizes and pixel intensities were converted to a log10 value to standardize the standard deviations between populations prior to statistical analysis. Statistical significance was determined using analysis of variance (ANOVA) between populations. An online ANOVA application was used to obtain P-values to identify the randomness in variance for both the size and pixel intensity across all included strains (http://www.physics.csbsju.edu/stats). P-values ≤ 0.05 were deemed significant. The obtained P-values for both cell size and pixel intensity were each <0.0001.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Mary Ard for preparation of EM samples and technical assistance. This work was supported by Public Health Service research Grant AI22362 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to D.C.K.

References

- Balish MF, Hahn TW, Popham PL, Krause DC. Stability of Mycoplasma pneumoniae cytadherence-accessory protein HMW1 correlates with its association with the triton shell. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3680–3688. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.12.3680-3688.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baseman JB, Morrison-Plummer J, Drouillard D, Puleo-Scheppke B, Tryon VV, Holt SC. Identification of a 32-kilodalton protein of Mycoplasma pneumoniae associated with hemadsorption. Isr J Med Sci. 1987;23:474–479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne ME, Rouch DA, Skurray RA. Nucleotide sequence analysis of IS256 from the Staphylococcus aureus gentamicin-tobramycin-kanamycin-resistance transposon Tn4001. Gene. 1989;81:361–367. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham ME, Caplan AJ. Structure, function and evolution of DnaJ: conservation and adaptation of chaperone function. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1998;3:28–36. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0028:sfaeod>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloward JM, Krause DC. Mycoplasma pneumoniae J-domain protein required for terminal organelle function. Mol Microbiol. 2009;71:1296–1307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr DM, Langer T, Douglas MG. DnaJ-like proteins: molecular chaperones and specific regulators of Hsp70. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:176–181. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirksen LB, Proft T, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Herrmann R, Krause DC. Sequence analysis and characterization of the hmw gene cluster of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Gene. 1996;171:19–25. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougan DA, Mogk A, Bukau B. Protein folding and degradation in bacteria: to degrade or not to degrade? That is the question. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1607–1616. doi: 10.1007/PL00012487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser CM, Gocayne JD, White O, Adams MD, Clayton RA, Fleischmann RD, et al. The minimal gene complement of Mycoplasma genitalium. Science. 1995;270:397–403. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5235.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman J. Folding of newly translated proteins in vivo: the role of molecular chaperones. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:603–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman J, Nimmesgern E, Ohtsuka K, Hartl FU. Folding of nascent polypeptide chains in a high molecular mass assembly with molecular chaperones. Nature. 1994;370:111–117. doi: 10.1038/370111a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobel U, Speth V, Bredt W. Filamentous structures in adherent Mycoplasma pneumoniae cells treated with nonionic detergents. J Cell Biol. 1981;91:537–543. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.2.537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene MK, Maskos K, Landry SJ. Role of the J-domain in the cooperation of Hsp40 with Hsp70. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6108–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn TW, Krebes KA, Krause DC. Expression in Mycoplasma pneumoniae of the recombinant gene encoding the cytadherence-associated protein HMW1 and identification of HMW4 as a product. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1085–1093. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.455985.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn TW, Willby MJ, Krause DC. HMW1 is required for cytadhesin P1 trafficking to the attachment organelle in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1270–1276. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.5.1270-1276.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn TW, Mothershed EA, Waldo RH, 3rd, Krause DC. Construction and analysis of a modified Tn4001 conferring chloramphenicol resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Plasmid. 1999;41:120–124. doi: 10.1006/plas.1998.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen EJ, Wilson RM, Baseman JB. Isolation of mutants of Mycoplasma pneumoniae defective in hemadsorption. Infect Immun. 1979;23:903–906. doi: 10.1128/iai.23.3.903-906.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartl FU, Hayer-Hartl M. Molecular chaperones in the cytosol: from nascent chain to folded protein. Science. 2002;295:1852–1858. doi: 10.1126/science.1068408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbring BM, Krause DC. Proteins P24 and P41 function in the regulation of terminal-organelle development and gliding motility in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2007a;189:7442–7449. doi: 10.1128/JB.00867-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbring BM, Krause DC. Cytoskeletal protein P41 is required to anchor the terminal organelle of the wall-less prokaryote Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2007b;63:44–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbring BM, Jordan JL, Krause DC. Mutant analysis reveals a specific requirement for protein P30 in Mycoplasma pneumoniae gliding motility. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:6281–6289. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.18.6281-6289.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasselbring BM, Jordan JL, Krause RW, Krause DC. Terminal organelle development in the cell wall-less bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:16478–16483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608051103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedreyda CT, Lee KK, Krause DC. Transformation of Mycoplasma pneumoniae with Tn4001 by electroporation. Plasmid. 1993;30:170–175. doi: 10.1006/plas.1993.1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson GP, Jensen GJ. Three-dimensional structure of Mycoplasma pneumoniae’s attachment organelle and a model for its role in gliding motility. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:376–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennessy F, Nicoll WS, Zimmermann R, Cheetham ME, Blatch GL. Not all J domains are created equal: implications for the specificity of Hsp40-Hsp70 interactions. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1697–1709. doi: 10.1110/ps.051406805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himmelreich R, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Pirkl E, Li BC, Herrmann R. Complete sequence analysis of the genome of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4420–4449. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu PC, Collier AM, Baseman JB. Surface parasitism by Mycoplasma pneumoniae of respiratory epithelium. J Exp Med. 1977;145:1328–1343. doi: 10.1084/jem.145.5.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang K, Flanagan JM, Prestegard JH. The influence of C-terminal extension on the structure of the ‘J-domain’ in E. coli DnaJ. Protein Sci. 1999;8:203–214. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan JL, Berry KM, Balish MF, Krause DC. Stability and subcellular localization of cytadherence-associated protein P65 in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:7387–7391. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.24.7387-7391.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan JL, Chang HY, Balish MF, Holt LS, Bose SR, Hasselbring BM, et al. Protein P200 is dispensable for Mycoplasma pneumoniae hemadsorption but not gliding motility or colonization of differentiated bronchial epithelium. Infect Immun. 2007;75:518–522. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01344-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenri T, Seto S, Horino A, Sasaki Y, Sasaki T, Miyata M. Use of fluorescent-protein tagging to determine the subcellular localization of Mycoplasma pneumoniae proteins encoded by the cytadherence regulatory locus. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:6944–6955. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.20.6944-6955.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DC. Mycoplasma pneumoniae cytadherence: unravelling the tie that binds. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:247–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DC, Balish MF. Structure, function, and assembly of the terminal organelle of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2001;198:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DC, Balish MF. Cellular engineering in a minimal microbe: structure and assembly of the terminal organelle of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:917–924. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DC, Baseman JB. Mycoplasma pneumoniae proteins that selectively bind to host cells. Infect Immun. 1982;37:382–386. doi: 10.1128/iai.37.1.382-386.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DC, Baseman JB. Inhibition of Mycoplasma pneumoniae hemadsorption and adherence to respiratory epithelium by antibodies to a membrane protein. Infect Immun. 1983;39:1180–1186. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1180-1186.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause DC, Leith DK, Wilson RM, Baseman JB. Identification of Mycoplasma pneumoniae proteins associated with hemadsorption and virulence. Infect Immun. 1982;35:809–817. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.3.809-817.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layh-Schmitt G, Harkenthal M. The 40- and 90-kDa membrane proteins (ORF6 gene product) of Mycoplasma pneumoniae are responsible for the tip structure formation and P1 (adhesin) association with the Triton shell. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:143–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layh-Schmitt G, Herrmann R. Localization and biochemical characterization of the ORF6 gene product of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae P1 operon. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2906–2913. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.7.2906-2913.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layh-Schmitt G, Hilbert H, Pirkl E. A spontaneous hemadsorption-negative mutant of Mycoplasma pneumoniae exhibits a truncated adhesin-related 30-kilodalton protein and lacks the cytadherence-accessory protein HMW1. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:843–846. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.3.843-846.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layh-Schmitt G, Podtelejnikov A, Mann M. Proteins complexed to the P1 adhesin of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Microbiology. 2000;146(Part 3):741–747. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-3-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberek K, Marszalek J, Ang D, Georgopoulos C, Zylicz M. Escherichia coli DnaJ and GrpE heat shock proteins jointly stimulate ATPase activity of DnaK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2874–2878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman RP, Clyde WA., Jr The interrelationship of virulence, cytadsorption, and peroxide formation in Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1969;131:1163–1167. doi: 10.3181/00379727-131-34061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng KE, Pfister RM. Intracellular structures of Mycoplasma pneumoniae revealed after membrane removal. J Bacteriol. 1980;144:390–399. doi: 10.1128/jb.144.1.390-399.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogle KF, Lee KK, Krause DC. Nucleotide sequence analysis reveals novel features of the phase-variable cytadherence accessory protein HMW3 of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1633–1641. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.4.1633-1641.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohki M, Tamura F, Nishimura S, Uchida H. Nucleotide sequence of the Escherichia coli dnaJ gene and purification of the gene product. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:1778–1781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papazisi L, Gorton TS, Kutish G, Markham PF, Browning GF, Nguyen DK, et al. The complete genome sequence of the avian pathogen Mycoplasma gallisepticum strain R(low) Microbiology. 2003;149:2307–2316. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pich OQ, Burgos R, Ferrer-Navarro M, Querol E, Pinol J. Mycoplasma genitalium mg200 and mg386 genes are involved in gliding motility but not in cytadherence. Mol Microbiol. 2006;60:1509–1519. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proft T, Hilbert H, Layh-Schmitt G, Herrmann R. The proline-rich P65 protein of Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a component of the Triton X-100-insoluble fraction and exhibits size polymorphism in the strains M129 and FH. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:3370–3378. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.12.3370-3378.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proft T, Hilbert H, Plagens H, Herrmann R. The P200 protein of Mycoplasma pneumoniae shows common features with the cytadherence-associated proteins HMW1 and HMW3. Gene. 1996;171:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00014-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razin S, Jacobs E. Mycoplasma adhesion. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:407–422. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-3-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regula JT, Boguth G, Gorg A, Hegermann J, Mayer F, Frank R, Herrmann R. Defining the mycoplasma ‘cytoskeleton’: the protein composition of the Triton X-100 insoluble fraction of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae determined by 2-D gel electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Microbiology. 2001;147:1045–1057. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-4-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Arroyo CE, Jordan J, Peacock SJ, Willby MJ, Farmer MA, Krause DC. Mycoplasma pneumoniae protein P30 is required for cytadherence and associated with proper cell development. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1079–1087. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.4.1079-1087.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto S, Layh-Schmitt G, Kenri T, Miyata M. Visualization of the attachment organelle and cytadherence proteins of Mycoplasma pneumoniae by immunofluorescence microscopy. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1621–1630. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.5.1621-1630.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobeslavsky O, Prescott B, Chanock RM. Adsorption of Mycoplasma pneumoniae to neuraminic acid receptors of various cells and possible role in virulence. J Bacteriol. 1968;96:695–705. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.3.695-705.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens MK, Krause DC. Localization of the Mycoplasma pneumoniae cytadherence-accessory proteins HMW1 and HMW4 in the cytoskeletonlike Triton shell. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1041–1050. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1041-1050.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan CS, Tremblay JD, Fewell SW, Lewis JA, Brodsky JL, Pipas JM. Species-specific elements in the large T-antigen J domain are required for cellular transformation and DNA replication by simian virus 40. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5749–5757. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.15.5749-5757.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szabo A, Korszun R, Hartl FU, Flanagan J. A zinc finger-like domain of the molecular chaperone DnaJ is involved in binding to denatured protein substrates. EMBO J. 1996;15:408–417. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tully JG, Whitcomb RF, Clark HF, Williamson DL. Pathogenic mycoplasmas: cultivation and vertebrate pathogenicity of a new spiroplasma. Science. 1977;195:892–894. doi: 10.1126/science.841314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waites KB. New concepts of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections in children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;36:267–278. doi: 10.1002/ppul.10346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh P, Bursac D, Law YC, Cyr D, Lithgow T. The J-protein family: modulating protein assembly, disassembly and translocation. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:567–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner J, 3rd, Zimmerman CU, Gohlmann HW, Herrmann R. Transcription profiles of the bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae grown at different temperatures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6306–6320. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willby MJ, Krause DC. Characterization of a Mycoplasma pneumoniae hmw3 mutant: implications for attachment organelle assembly. J Bacteriol. 2002;184:3061–3068. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.3061-3068.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Skolnick J, Zhang Y. Ab initio modeling of small proteins by iterative TASSER simulations. BMC Biol. 2007;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. Template-based modeling and free modeling by I-TASSER in CASP7. Proteins. 2007;69(Suppl 8):108–117. doi: 10.1002/prot.21702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. I-TASSER server for protein 3D structure prediction. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:40. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]