Abstract

Background

Combination of selumetinib plus docetaxel provided clinical benefit in a previous phase II trial for patients with KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The phase II SELECT-2 trial investigated safety and efficacy of selumetinib plus docetaxel for patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC.

Patients and methods

Patients who had disease progression after first-line anti-cancer therapy were randomized (2 : 2 : 1) to selumetinib 75 mg b.i.d. plus docetaxel 60 or 75 mg/m2 (SEL + DOC 60; SEL + DOC 75), or placebo plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 (PBO + DOC 75). Patients were initially enrolled independently of KRAS mutation status, but the protocol was amended to include only patients with centrally confirmed KRAS wild-type NSCLC. Primary end point was progression-free survival (PFS; RECIST 1.1); statistical analyses compared each selumetinib group with PBO + DOC 75 for KRAS wild-type and overall (KRAS mutant or wild-type) populations.

Results

A total of 212 patients were randomized; 69% were KRAS wild-type. There were no statistically significant improvements in PFS or overall survival for overall or KRAS wild-type populations in either selumetinib group compared with PBO + DOC 75. Overall population median PFS for SEL + DOC 60, SEL + DOC 75 compared with PBO + DOC 75 was 3.0, 4.2, and 4.3 months, HRs: 1.12 (90% CI: 0.8, 1.61) and 0.92 (90% CI: 0.65, 1.31), respectively. In the overall population, a higher objective response rate (ORR; investigator assessed) was observed for SEL + DOC 75 (33%) compared with PBO + DOC 75 (14%); odds ratio: 3.26 (90% CI: 1.47, 7.95). Overall the tolerability profile of SEL + DOC was consistent with historical data, without new or unexpected safety concerns identified.

Conclusion

The primary end point (PFS) was not met. The higher ORR with SEL + DOC 75 did not translate into prolonged PFS for the overall or KRAS wild-type patient populations. No clinical benefit was observed with SEL + DOC in KRAS wild-type patients compared with docetaxel alone. No unexpected safety concerns were reported.

Trial identifier

Clinicaltrials.gov NCT01750281.

Keywords: advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), metastatic disease, MEK1/2, KRAS, selumetinib, docetaxel

Introduction

Selumetinib (AZD6244, ARRY-142886) is an oral, potent and highly selective, allosteric MEK1/2 inhibitor [1] with a short half-life [2, 3]. The RAS/RAF/MEK/ERK (RAS-ERK) pathway converges at MEK1/2, whose only known substrates are ERK1/2 [4, 5]. This pathway is implicated in growth and progression of various cancers, and can be activated by mutations in several components, such as RAS, BRAF or NF1 [4, 6, 7].

Results of a Phase II trial demonstrated that selumetinib in combination with docetaxel (SEL + DOC) improved clinical outcomes for patients with KRAS-mutant (KRASm) advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [8]. Selumetinib has also demonstrated activity in pre-clinical KRAS wild-type models, which suggested that SEL + DOC may provide clinical benefit to patients with NSCLC with activation of the RAS-ERK pathway, independent of a KRAS mutation [5]. Moreover, clinical responses to selumetinib have been reported in patients whose tumours do not harbour KRAS mutations [9], and at the time of initiation of the present trial, emerging data suggested that combining MEK inhibitors with docetaxel may provide clinical benefit to patients with KRAS wild-type NSCLC [10, 11]. Based on these promising pre-clinical and clinical data, the phase II SELECT-2 trial (NCT01750281) was initiated to compare the clinical benefit of SEL + DOC with docetaxel monotherapy, in patients with advanced or metastatic NSCLC. The SELECT-2 trial was carried out in parallel to the phase III SELECT-1 trial which failed to show benefit of adding selumetinib to docetaxel for treating patients with advanced KRASm NSCLC [12]. Two patient populations were investigated in SELECT-2: those with KRAS wild-type tumours, and the overall population, including patients with KRAS mutations or wild-type tumours, allowing comparison of effects of the combination and monotherapy between populations.

Patients and methods

Patients

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years, with a World Health Organization (WHO) performance status (PS) 0/1, who had disease progression after first-line treatment of locally advanced or metastatic NSCLC due to progression of disease while on first-line therapy or relapse of disease following remission from first-line therapy. Patients were excluded if they had mixed small and NSCLC histology, had received >1 prior anti-cancer drug regimen for advanced or metastatic NSCLC (platinum-based doublet chemotherapy, other single agent anti-cancer therapy, or combination regimen), or had received prior treatment with an MEK inhibitor or any docetaxel containing regimen. Patients were initially enrolled regardless of KRAS mutation status with no testing for mutation status required. However, in September 2013, after trial initiation, a protocol amendment required patients to have a prospectively, centrally confirmed absence of a KRAS mutation (no mutation detected; referred to as KRAS wild-type) using the cobas® KRAS Mutation Test (Roche Molecular Systems). The amendment was introduced to investigate a population enriched with patients with KRAS wild-type tumours in order to characterize the activity of selumetinib in a robustly defined KRAS wild-type population, in parallel to the SELECT-1 trial exploring the activity of selumetinib in patients with KRAS-mutant NSCLC [12].

All patients provided written informed consent before any study specific procedures. The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Study design

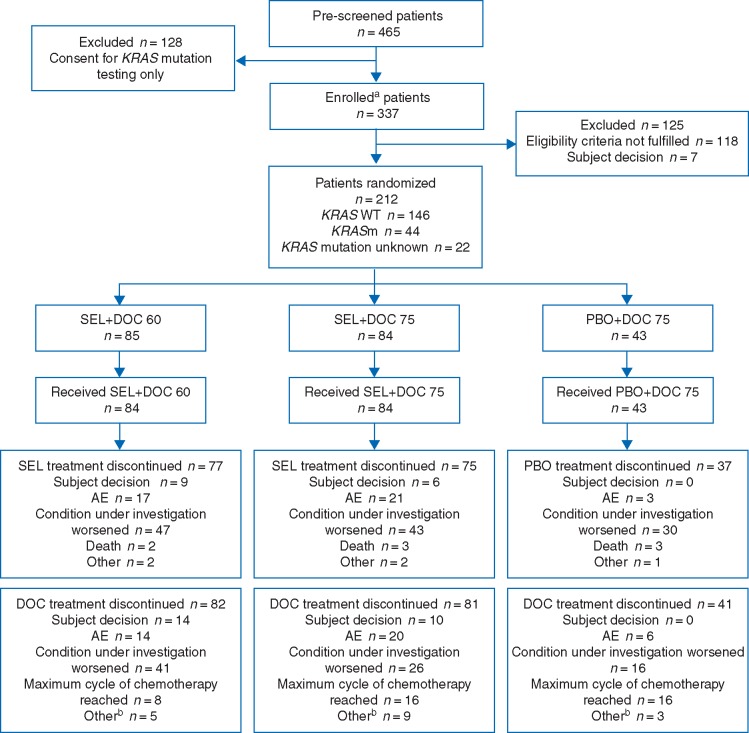

Patients were randomized using an interactive voice/web response system in a 2 : 2 : 1 ratio (Figure 1) to selumetinib 75 mg twice daily (b.i.d.) plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 (SEL + DOC 75), selumetinib 75 mg b.i.d. plus docetaxel 60 mg/m2 (SEL + DOC 60), or matched placebo plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 (PBO + DOC 75). Docetaxel was administered intravenously on day 1 of every 21-day cycle.

Figure 1.

Randomization and treatment. Data cut-off 27 January 2016. aInformed consent received. bAny reason not specifically recorded.

A protocol amendment (December 2013) required patients to receive pegylated Granulocyte-Colony Stimulating Factor (G-CSF; pegfilgrastim 6 mg) as a single injection within 24 h following each docetaxel administration, and not within 14 days of the next dose in accordance with local prescribing information. The amendment was introduced in order to reduce the rate of neutropenia and febrile neutropenia observed in the phase II study of SEL + DOC [8]. Before this, G-CSF could be administered but was not mandated.

Due to protocol amendments (September 2013) regarding KRAS status and patient selection, there were three patient subgroups: KRAS wild-type, KRAS-mutant, and KRAS unknown. All patients were expected to receive up to six docetaxel cycles. The investigator could reduce the number of cycles if significant toxicity developed. If docetaxel was discontinued, patients continued to receive selumetinib/placebo until objective disease progression, intolerable toxicity, or occurrence of another discontinuation criterion. Patients could continue to receive selumetinib/placebo treatment as long as the investigator considered them as continuing to derive clinical benefit in the absence of significant toxicity, and if it did not contravene local practice. Patients experiencing toxicity considered treatment related had a dose reduction or were withheld from further treatment until resolution of the toxicity. Patients initially on docetaxel 75 mg/m2 were reduced to 55 mg/m2, and for initial dose 60 mg/m2 the dose reduction was to 45 mg/m2.

End points and study assessments

The primary objective was to assess efficacy in terms of PFS by investigative site review of computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scans, according to RECIST 1.1. Secondary objectives were to further assess efficacy in terms of overall survival (OS), objective response rate (ORR), duration of response (DoR), safety, and tolerability. Tumour evaluations were carried out for all randomized patients at screening and every 6 weeks thereafter until evidence of disease progression by RECIST 1.1, withdrawal of consent, or death. Patients were followed-up for survival status every 8 weeks after treatment discontinuation until withdrawal of consent, death, or the end of the trial. Adverse events (AEs) were recorded as MedDRA (version 18.1) preferred terms and according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE; version 4.0) from the time of informed consent until 30 (±7) days after the last treatment dose.

Sample size and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS® Version 9.2, where SEL + DOC 60 and SEL + DOC 75 groups were each compared with the PBO + DOC 75 group. Approximately 225 patients were planned to be randomized between treatment groups to obtain ∼107 progression events for each treatment comparison (174 events across all treatment groups). In the analyses, a hazard ratio (HR) <1.0 favours SEL + DOC, and >1.0 favours PBO + DOC. If the true PFS HR was 0.6 (corresponding to a 1.7 month improvement in median PFS over an estimate of 2.5 months for PBO + DOC 75), then 174 events would provide 80% power to demonstrate a statistically significant difference for PFS, assuming a 10% two-sided significance level. Assuming that all patients recruited before the protocol amendment to enrol only patients with KRAS wild-type tumours progressed before data cut-off, then 109 out of the 174 events observed at the time of data cut-off will be within the KRAS wild-type subgroup. If the true HR for both comparisons versus placebo is 0.6, this number of events will provide ∼62.5% power to demonstrate a statistically significant difference for PFS within the KRAS wild-type subgroup, assuming a 10% two-sided significance level.

Efficacy end points were analysed for all patient populations. PFS and OS were analysed using a Cox proportional hazards model. ORR was assessed by investigator assessment and analysed using a standard logistic regression model. DoR and percentage change in tumour size from baseline to week 6 were summarized.

Results

Patient disposition

Between 18 December 2012 and 6 November 2015, 337 patients were enrolled at 55 centres across 8 countries. In total, 212 patients were randomized to SEL + DOC 75 (n = 84), SEL + DOC 60 (n = 85), or PBO + DOC 75 (n = 43), and 211 patients received at least one dose of treatment (Figure 1). At the time of data cut-off (27 January 2016) 189 patients (89%) had discontinued selumetinib/placebo.

Patient demographics were well balanced between treatment groups (Table 1). The majority of patients [146/212 (69%)] were centrally confirmed KRAS wild-type, with the proportion of these patients balanced between treatment groups. Of the remaining patients, 44 (21%) were KRASm and 22 (10%) had an unknown KRAS mutation status. Previous anti-cancer therapies were balanced between treatment groups. The majority of patients [187/212 (89%)] had received first-line doublet platinum therapies.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics

| Characteristic | SEL + DOC 60 n = 85 | SEL + DOC 75 n = 84 | PBO + DOC n = 43 | Total n = 212 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 62.4 (8.5) | 60.4 (9.4) | 63.6 (7.8) | 61.8 (8.8) |

| Median (range) | 62 (41–84) | 61 (38–79) | 62 (47–76) | 62 (38–84) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | ||||

| <50 | 5 (6) | 11 (13) | 2 (5) | 18 (9) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 19 (22) | 26 (31) | 16 (37) | 61 (29) |

| Male | 66 (78) | 58 (69) | 27 (63) | 151 (71) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| White | 80 (94) | 78 (93) | 41 (95) | 199 (94) |

| Black or African American | 5 (6) | 5 (6) | 0 | 10 (5) |

| Other | 0 | 1 (1) | 2 (5) | 3 (1) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 20 (24) | 16 (19) | 8 (19) | 44 (21) |

| Non-hispanic or Latino | 26 (31) | 29 (35) | 19 (44) | 74 (35) |

| Unknowna | 39 (46) | 39 (46) | 16 (37) | 94 (44) |

| WHO PS | ||||

| 0 | 40 (47) | 39 (46) | 25 (58) | 104 (49) |

| 1 | 45 (53) | 45 (54) | 18 (42) | 108 (51) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | ||||

| Never | 8 (9) | 9 (11) | 3 (7) | 20 (9) |

| Current | 24 (28) | 20 (24) | 11 (26) | 55 (26) |

| Former | 53 (62) | 55 (66) | 29 (67) | 137 (65) |

| KRAS mutation status | ||||

| Positive | 15 (18) | 19 (23) | 10 (23) | 44 (21) |

| No mutation detected | 62 (73) | 54 (64) | 30 (70) | 146 (69) |

| Unknown | 8 (9) | 11 (13) | 3 (7) | 22 (10) |

Patient did not consider themselves to belong to a specific ethnic group.

DOC, docetaxel; PBO, placebo; SD, standard deviation; SEL, selumetinib; WHO PS, World Health Organization Performance Status.

Efficacy

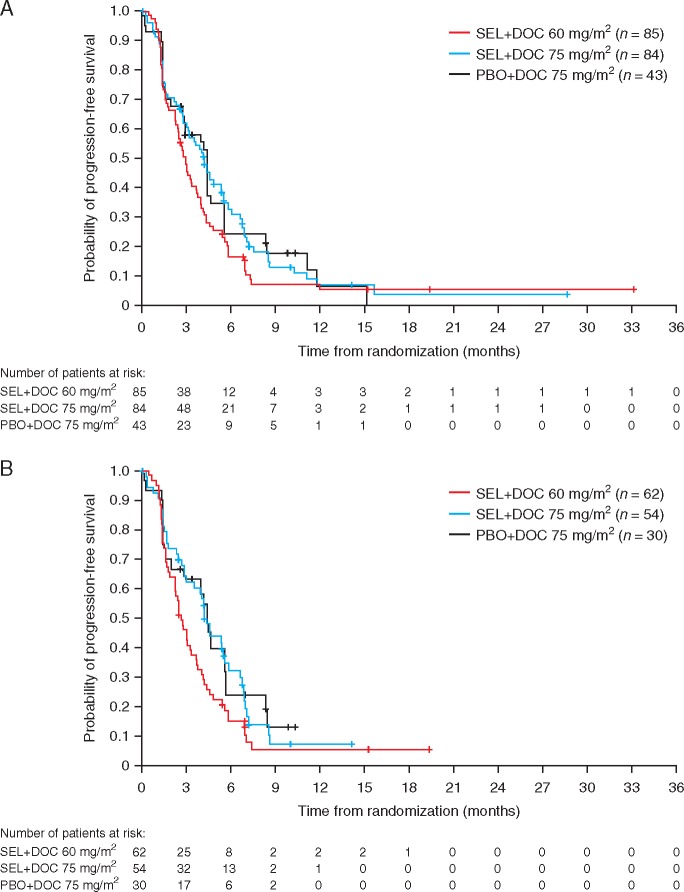

At data cut-off, 180 patients had experienced a progression event (85% maturity): 75 (88%) patients receiving SEL + DOC 60, 69 (82%) patients receiving SEL + DOC 75, and 36 (84%) receiving PBO + DOC 75. There was no statistically significant or clinically meaningful improvement in PFS in either the SEL + DOC 60 group [HR 1.12, 90% confidence interval (CI) 0.8, 1.61; two-sided P = 0.584], or the SEL + DOC 75 group (HR 0.92; 90% CI 0.65, 1.31; two-sided P = 0.690), compared with the PBO + DOC 75 group in the overall population (Figure 2). Median PFS was 3.0 months with SEL + DOC 60 (95% CI: 0.75, 1.72), 4.2 months with SEL + DOC 75 (95% CI: 0.61, 1.40), and 4.3 months with PBO + DOC 75. The subgroup analyses for PFS in the overall population were broadly consistent with results from the primary analysis of PFS, except WHO PS (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). KRAS wild-type patients had similar progression status to the overall population, with no improvement in PFS over the PBO + DOC 75 group with SEL + DOC 60 (HR: 1.37; 90% CI: 0.89, 2.14; two-sided P = 0.228) or SEL + DOC 75 (HR: 1.00; 90% CI: 0.65, 1.55; two-sided P = 0.994). Due to the small number of patients with KRASm NSCLC, efficacy end points were not analysed for this subgroup.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of progression-free survival for the overall population (A) and the KRAS wild-type population (B).

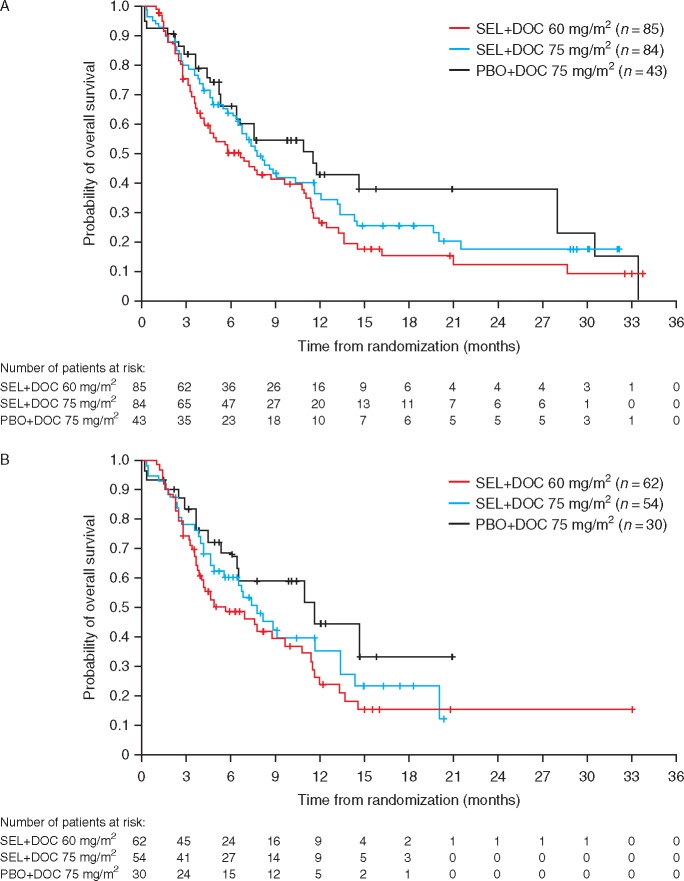

At data cut-off, 147 deaths had occurred (69% maturity). In the overall population, there was no difference in OS between the PBO + DOC 75 and SEL + DOC 60 (HR 1.43, 90% CI: 0.97, 2.13), or SEL + DOC 75 groups (HR 1.18, 90% CI: 0.8, 1.78) (Figure 3). Median OS was 5.7 months with SEL + DOC 60, 7.7 months with SEL + DOC 75, and 11.5 months with PBO + DOC 75, with hazard ratios for OS favouring the control arm. OS in the KRAS wild-type subgroup was similar to the overall population when comparing treatment groups between the two populations.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of overall survival for the overall population (A) and the KRAS wild-type population (B).

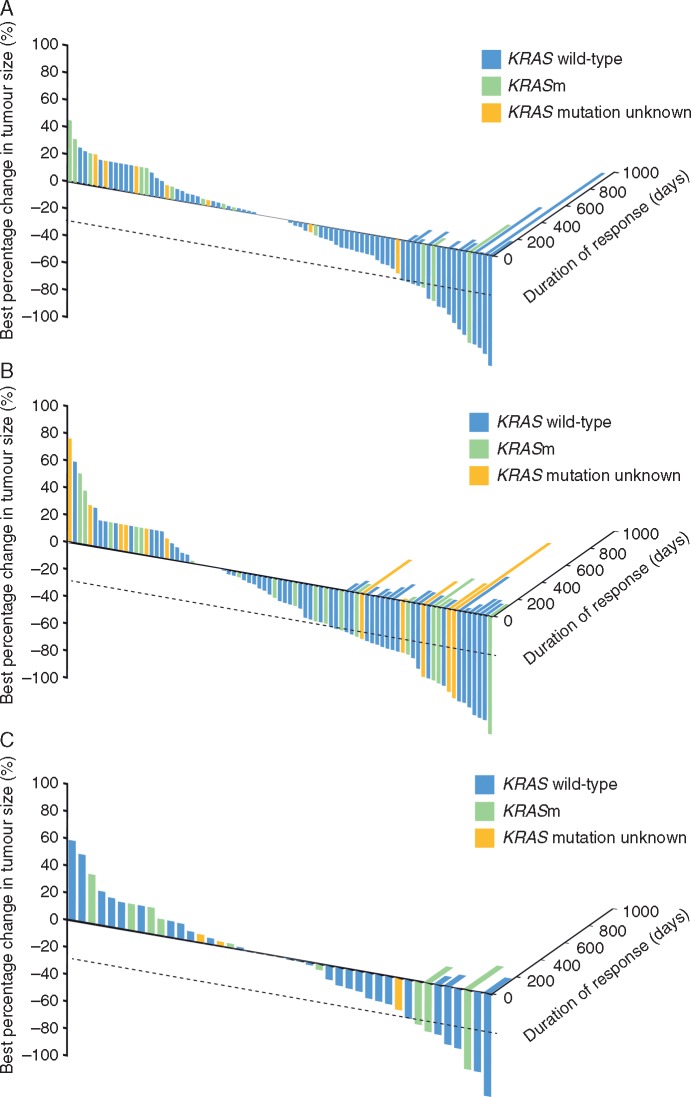

ORR in the overall population was 33% with SEL + DOC 75, 18% with SEL + DOC 60, and 14% with PBO + DOC 75, with a similar trend observed in the KRAS wild-type population. The improvement in ORR with SEL + DOC 75 was numerically higher when compared with PBO + DOC 75 in both the overall population and KRAS wild-type patients, however, responses were not durable (overall population OR: 3.26, 90% CI: 1.47, 7.95, P = 0.020; KRAS wild-type OR: 3.21, 90% CI: 1.22, 9.73, P = 0.061).

Median DoR for the SEL + DOC 60, SEL + DOC 75, and PBO + DOC 75 groups was 108, 136, and 183 days in the overall population, and 133, 127, and 87 days in KRAS wild-type patients, respectively. Percentage change in target lesion size at week 6 from baseline was significantly improved in the SEL + DOC 75 group compared with the PBO + DOC 75 group in the overall population (P = 0.02), however, the median DoR was shorter at 136 and 183 days, respectively (Figure 4). No difference was observed between the SEL + DOC 60 and the PBO + DOC 75 groups (P = 0.21). There was no difference in percentage change in target lesion size in the KRAS wild-type subgroup for either of these comparisons. The DoR between SEL + DOC 75 and PBO + DOC 75 was comparable (133 and 127 days, respectively), but a lower DoR was observed for the SEL + DOC 60 group (87 days).

Figure 4.

Best change in tumour size and associated duration of response for the SEL + DOC 60 (A), SEL + DOC 75 (B) and PBO + DOC 75 (C) cohorts.

Safety and tolerability

The majority of patients experienced at least one AE (Table 2), and the frequency of AEs was similar between KRAS mutation subgroups (not shown). The most frequent AEs across treatment groups (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online) were diarrhoea [41 (49%) patients in the SEL + DOC 60 group; 38 (45%) in the SEL + DOC 75 group; 13 (30%) in the PBO + DOC 75 group], rash [23 (27%), 29 (35%), and 9 (21%) patients, respectively], and oedema peripheral [17 (20%), 29 (35%), and 8 (19%) patients, respectively]. The most commonly reported grade ≥3 AE was neutropenia (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Serious AEs (SAEs) of pneumonia and neutropenia were reported in each treatment group, with pneumonia reported in 10 (12%), 4 (5%), and 1 (2%) patients and neutropenia reported in 1 (1%), 4 (5%), and 3 (7%) patients in the SEL + DOC 60, SEL + DOC 75, and PBO + DOC 75 groups, respectively. Thirteen patients had a SAE with an outcome of death, five of which were potentially related to selumetinib and docetaxel (SEL + DOC 60 [n = 2] haematemesis and haemoptysis; SEL + DOC 75 [n = 3] chemical peritonitis and two sepsis events). The mean actual treatment durations in the SEL + DOC 60, SEL + DOC 75, and PBO + DOC 75 groups were 91.1, 126.7, and 131.3 days, respectively. There was a similar pattern observed in the KRAS wild-type subgroup.

Table 2.

Summary of adverse events

| Overall |

KRAS wild-type |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE category, n (%) | SEL + DOC 60 (n = 84) | SEL + DOC 75 (n = 84) | PBO + DOC 75 (n = 43) | SEL + DOC 60 (n = 61) | SEL + DOC 75 (n = 54) | PBO + DOC 75 (n = 30) |

| Any AE | 81 (96) | 83 (99) | 39 (91) | 59 (97) | 53 (98) | 27 (90) |

| Any AE ≥CTCAE grade 3 | 50 (60) | 53 (63) | 23 (54) | 37 (61) | 30 (56) | 14 (47) |

| Any SAEa | 40 (48) | 38 (45) | 16 (37) | 27 (44) | 23 (43) | 10 (33) |

| Any SAE causally related to SEL/PBOa | 19 (23) | 18 (21) | 7 (16) | 12 (20) | 14 (26) | 3 (10) |

| Any SAE causally related to DOCa | 15 (18) | 19 (23) | 9 (21) | 11 (18) | 13 (24) | 4 (13) |

| Any AE leading to hospitalization | 36 (43) | 36 (43) | 14 (33) | 23 (38) | 23 (43) | 10 (33) |

| Any AE with outcome of death | 5 (6) | 7 (8) | 1 (2) | 5 (8) | 5 (9) | 1 (3) |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation of SEL/PBO | 16 (19) | 21 (25) | 3 (7) | 12 (20) | 14 (26) | 2 (7) |

| Causally related to SEL/PBOa | 12 (14) | 15 (18) | 2 (5) | 8 (13) | 12 (22) | 1 (3) |

| Any AE leading to dose interruption of SEL/PBO | 29 (35) | 24 (29) | 8 (19) | 16 (26) | 11 (20) | 7 (23) |

| Any AE leading to dose reduction of SEL/PBO | 16 (19) | 19 (23) | 2 (5) | 11 (18) | 11 (20) | 1 (3) |

| Any AE leading to discontinuation of DOC | 14 (17) | 19 (23) | 6 (14) | 10 (16) | 11 (20) | 5 (17) |

| Causally related to DOC | 10 (12) | 16 (19) | 5 (12) | 6 (10) | 9 (17) | 4 (13) |

| Any AE leading to dose delay of DOC | 15 (18) | 10 (12) | 5 (12) | 10 (16) | 6 (11) | 5 (17) |

| Any AE leading to dose reduction of DOC | 7 (8) | 6 (7) | 3 (7) | 4 (7) | 3 (6) | 3 (10) |

Assessed by investigator.

AE, adverse event; CTCAE, Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events; DOC, docetaxel; PBO, placebo; SAE, serious adverse event; SEL, selumetinib.

Discussion

The phase II SELECT-2 trial explored the efficacy and safety of selumetinib in combination with two different docetaxel doses. The primary end point of PFS was not met, therefore the hypothesis based on preclinical and clinical evidence that SEL + DOC provides a clinical benefit in patients with KRAS wild-type advanced NSCLC was not confirmed.

Addition of selumetinib to docetaxel treatment did not improve efficacy, which could be due to a large number of deaths in the absence of disease progression in the combination cohorts. This indicates the rapid progression of disease, which prevents imaging and documentation of the disease, or the patient being unable to undergo analytic procedures. Overall outcomes of this trial were broadly similar to those observed in the phase III SELECT-1 trial, in which patients received selumetinib 75 mg b.i.d. or placebo plus docetaxel 75 mg/m2 on day 1 of every 21 day cycle, which was conducted in parallel with a larger KRASm NSCLC population [12]. The MEK inhibitor trametinib in combination with docetaxel (75 mg/m2) in a phase I/Ib trial for patients with advanced NSCLC (n = 46), had preliminary efficacy in terms of ORR in both KRASm and KRAS wild-type NSCLC, exceeding expectations for either agent alone [13]. There was an indication of cardiac toxicity in the trametinib plus docetaxel combination, with two patients with a history of cardiovascular conditions experiencing Grade 5 AEs of cardiac arrest (n = 1) and cerebrovascular accident (n = 1) [13].

Safety data in the SELECT-2 trial were consistent with historical data for docetaxel, and the emerging safety profile of selumetinib [12]. To compensate for any potential selumetinib augmented toxicity of docetaxel, as observed in the phase II trial of the combination [8], one group received a lower dose of docetaxel (60 mg/m2). Safety findings were generally similar between the selumetinib-containing treatment groups, and the administration of prophylactic G-CSF resulted in a lower rate of neutropenia, severe neutropenia and febrile neutropenia compared with the phase II combination trial [8]. Although SELECT-2 was not powered for a comparison between the combination arms, data suggest SEL + DOC 60 did not improve tolerability of the combination and patients may have derived less clinical benefit compared with those receiving SEL + DOC 75. This is consistent with a study for second-line advanced breast cancer that reported a correlation between the dose of docetaxel and tumour response [14].

As this trial took place during the period in which anti-cancer immunotherapies were still in development, only three patients had previously received immunotherapy; the majority had received a first-line platinum-based chemotherapy regimen. As the treatment landscape is changing, the emergence of immunotherapy means a limitation of the SELECT-2 trial is that the efficacy and safety of SEL + DOC following first-line immunotherapy has not been assessed.

KRAS mutations are the most common oncogenic driver in lung cancer, however, effective therapies have yet to be developed. Various mechanisms of RAS-ERK pathway activation, independent of KRAS, could be potential novel targets for therapeutic development including NF1, B-RAF, and receptor tyrosine kinases [7, 15]. A preclinical study using various model cell-lines identified an MEK transcriptome signature [16], also found expressed in NSCLC tumour tissue samples, which is predictive of sensitivity to selumetinib for an overlapping but distinct population to that identified by KRASm testing [17]. This suggests there could be KRAS wild-type subpopulations that may benefit from MEK inhibitor treatment. BRAF inhibitors decrease activation of the MEK-ERK pathway independently of RAS, and have been investigated in BRAF mutant melanoma [18]. However, BRAF inhibitors paradoxically cause activation of the MEK/ERK pathway, primarily through CRAF activation, which consequently diminishes the therapeutic efficacy [6]. Efficacy of MEK inhibition may be compromised by relief of feedback inhibition that occurs when the pathway is inhibited, and may result in reactivation of the pathway [19].

SELECT-2 did not demonstrate improved PFS in KRAS wild-type patients, however, there were some patients with a long DoR and ≥30% decrease baseline tumour size, for which there was no common factor identified. Therefore, along with the outcomes of the SELECT-1 trial in patients with KRASm NSCLC, the importance of assessing novel biomarkers to identify patient subgroups that may benefit from treatment with MEK inhibitors is highlighted. The combined outcome of the SELECT-1 and SELECT-2 trials demonstrates that selumetinib currently does not have a role as a second-line treatment of patients with advanced NSCLC.

Ethical approval

All patients provided written informed consent before any study specific procedures. The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the patients, investigators, and institutions that were involved in this study. We also thank James L Sherwood of Personalised Healthcare and Biomarkers, AstraZeneca, for supporting KRAS testing at the central laboratory during this trial. Medical writing services were provided by Natalie Griffiths PhD, of iMed Comms, an Ashfield Company, Part of UDG Healthcare plc, and were funded by AstraZeneca.

Funding

AstraZeneca (no grant number applies).

Disclosure

AK, AM, EK, KB, GM, PS, and SL are employees of and have stocks/options in AstraZeneca. PJ has received personal fees from AstraZeneca for the work under consideration for publication, and has also received personal fees for activities outside the submitted work from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Merrimack Pharmaceuticals, Genentech/Roche, Ariad Pharmaceuticals, Chugai Pharmaceuticals, Ignyta, Loxo, PUMA, Daiichi Sankyo, and Astellas Pharmaceuticals. WE has received personal fees for activities outside the submitted work from AstraZeneca, BMS, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, Merck/MSD, Pfizer, Bayer, Celgene, Eli Lilly, and Hexal. GG has received personal fees for activities outside the submitted work from Roche/Genentech, MSD and AstraZeneca. JCS has received personal fees for activities outside the submitted work from Astex, Clovis, GSK, Gammamabs, Lilly, MSD, Mission Therapeutics, Merus, Novartis, Pfizer, Pharmamar, Pierre Fabre, Roche Genentech, Sanofi, Servier, Symphogen, and Takeda. AF, CS, DC, ES, GO, JF, PL, and SL have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Yeh TC, Marsh V, Bernat BA. et al. Biological characterization of ARRY-142886 (AZD6244), a potent, highly selective mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 1/2 inhibitor. Clin Cancer Res 2007; 13(5): 1576–1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Banerji U, Camidge DR, Verheul HM. et al. The first-in-human study of the hydrogen sulfate (Hyd-sulfate) capsule of the MEK1/2 inhibitor AZD6244 (ARRY-142886): a phase I open-label multicenter trial in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2010; 16(5): 1613–1623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Denton CL, Gustafson DL.. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of AZD6244 (ARRY-142886) in tumor-bearing nude mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2011; 67(2): 349–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roberts PJ, Stinchcombe TE.. KRAS mutation: should we test for it, and does it matter? J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(8): 1112–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Davies BR, Logie A, McKay JS. et al. AZD6244 (ARRY-142886), a potent inhibitor of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase 1/2 kinases: mechanism of action in vivo, pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic relationship, and potential for combination in preclinical models. Mol Cancer Ther 2007; 6(8): 2209–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hatzivassiliou G, Song K, Yen I. et al. RAF inhibitors prime wild-type RAF to activate the MAPK pathway and enhance growth. Nature 2010; 464(7287): 431–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dombi E, Baldwin A, Marcus LJ. et al. Activity of selumetinib in neurofibromatosis type 1-related plexiform neurofibromas. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(26): 2550–2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jänne PA, Shaw AT, Pereira JR. et al. Selumetinib plus docetaxel for KRAS-mutant advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomised, multicentre, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14(1): 38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Farley J, Brady WE, Vathipadiekal V. et al. Selumetinib in women with recurrent low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14(2): 134–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kelly K, Mazieres J, Leighl NB. et al. Oral MEK1/MEK2 inhibitor trametinib (GSK1120212) in combination with pemetrexed for KRAS-mutant and wild-type (WT) advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a phase I/Ib trial. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(Suppl 15), Abstract 8027. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gandara D, Hiret S, Blumenschein G. et al. Oral MEK1/MEK2 inhibitor trametinib (GSK1120212) in combination with docetaxel in KRAS-mutant and wild-type (WT) advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): a phase I/Ib trial. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(Suppl): 8028. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jänne PA, Heuvel MMvd, Barlesi F. et al. Effect of selumetinib plus docetaxel compared with docetaxel alone and progression-free survival in patients with KRAS-mutant advanced non-small cell lung cancer: the SELECT-1 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017; 317(18): 1844–1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gandara DR, Leighl N, Delord JP. et al. A phase 1/1b study evaluating trametinib plus docetaxel or pemetrexed in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2017; 12(3): 556–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harvey V, Mouridsen H, Semiglazov V. et al. Phase III trial comparing three doses of docetaxel for second-line treatment of advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24(31): 4963–4970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chappell WH, Steelman LS, Long JM. et al. Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/PTEN/Akt/mTOR inhibitors: rationale and importance to inhibiting these pathways in human health. Oncotarget 2011; 2(3): 135–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dry JR, Pavey S, Pratilas CA. et al. Transcriptional pathway signatures predict MEK addiction and response to selumetinib (AZD6244). Cancer Res 2010; 70(6): 2264–2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brant RG, Sharpe A, Liptrot T. et al. Clinically viable gene expression assays with potential for predicting benefit from MEK inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23(6): 1471–1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Holderfield M, Deuker MM, McCormick F, McMahon M.. Targeting RAF kinases for cancer therapy: BRAF-mutated melanoma and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer 2014; 14(7): 455–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lito P, Saborowski A, Yue J. et al. Disruption of CRAF-mediated MEK activation is required for effective MEK inhibition in KRAS mutant tumors. Cancer Cell 2014; 25(5): 697–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.