Abstract

Background

In the phase III LUX-Head & Neck 1 (LUX-H&N1) trial, second-line afatinib significantly improved progression-free survival (PFS) versus methotrexate in patients with recurrent/metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (R/M HNSCC). Here, we evaluated association of prespecified biomarkers with efficacy outcomes in LUX-H&N1.

Patients and methods

Randomized patients with R/M HNSCC and progression following ≥2 cycles of platinum therapy received afatinib (40 mg/day) or methotrexate (40 mg/m2/week). Tumor/serum samples were collected at study entry for patients who volunteered for inclusion in biomarker analyses. Tumor biomarkers, including p16 (prespecified subgroup; all tumor subsites), EGFR, HER2, HER3, c-MET and PTEN, were assessed using tissue microarray cores and slides; serum protein was evaluated using the VeriStrat® test. Biomarkers were correlated with efficacy outcomes.

Results

Of 483 randomized patients, 326 (67%) were included in the biomarker analyses; baseline characteristics were consistent with the overall study population. Median PFS favored afatinib over methotrexate in patients with p16-negative [2.7 versus 1.6 months; HR 0.70 (95% CI 0.50–0.97)], EGFR-amplified [2.8 versus 1.5 months; HR 0.53 (0.33–0.85)], HER3-low [2.8 versus 1.8 months; HR 0.57 (0.37–0.88)], and PTEN-high [1.6 versus 1.4 months; HR 0.55 (0.29–1.05)] tumors. Afatinib also improved PFS in combined subsets of patients with p16-negative and EGFR-amplified tumors [2.7 versus 1.5 months; HR 0.47 (0.28–0.80)], and patients with p16-negative tumors who were EGFR therapy-naïve [4.0 versus 2.4 months; HR 0.55 (0.31–0.98)]. PFS was improved in afatinib-treated patients who were VeriStrat ‘Good’ versus ‘Poor’ [2.7 versus 1.5 months; HR 0.71 (0.49–0.94)], but no treatment interaction was observed. Afatinib improved tumor response versus methotrexate in all subsets analyzed except for those with p16-positive disease (n = 35).

Conclusions

Subgroups of HNSCC patients who may achieve increased benefit from afatinib were identified based on prespecified tumor biomarkers (p16-negative, EGFR-amplified, HER3-low, PTEN-high). Future studies are warranted to validate these findings.

Clinical trial registration

Keywords: afatinib, methotrexate, HNSCC, biomarker, phase III, EGFR

Key Message

Biomarkers reflecting human papillomavirus status (p16), ErbB- and PI3K-pathway regulation appear to predict head and neck cancer patients who may benefit from afatinib over methotrexate. Combined biomarkers (p16-negative and EGFR amplification) identified a subset who may achieve clinically meaningful benefit with afatinib, while prior EGFR-targeted therapy was associated with reduced benefit.

Introduction

Patients with recurrent and/or metastatic (R/M) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) who have progressed on/after platinum-based therapy have poor prognosis and few effective treatment options. Recent clinical studies have evaluated afatinib, an irreversible ErbB family blocker that inhibits signaling from all ErbB family members [epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), human EGFR 2 (HER2), HER3, HER4], in this setting [1]. In the phase III LUX-Head & Neck 1 (LUX-H&N1) trial, afatinib improved progression-free survival [PFS; median 2.6 versus 1.7 months; hazard ratio (HR) 0.80; P = 0.030] and patient-reported outcomes versus methotrexate as second-line treatment of R/M HNSCC [1].

While some molecular biomarkers have been associated with HNSCC prognosis, none are validated to predict treatment response, particularly to EGFR-targeted therapy [2]. Dysregulation of cell signaling factors, including EGFR- and PI3K-pathway-related factors at the gene and/or protein level in HNSCC, has been reported [2]. EGFR amplification has been detected in 13%–58% of HNSCC (depending on the definition), and increased EGFR protein expression in ∼90% of cases [2, 3]. There are few reports examining other ErbB family members in HNSCC; however, studies suggest that HER3 expression is associated with poor prognosis and resistance to EGFR-targeted therapy [4]. EGFR upregulation was also shown to increase HER2/HER3 signaling [2]. PTEN mutations have been reported in 9%–23% of HNSCC, with reduced PTEN protein expression in ∼30% of cases [3]. In addition to their individual correlations with HNSCC prognosis, the combined contributions of these components within the same signaling pathways suggest the potential for new single-agent and combination targeted therapies [2].

In oropharyngeal SCC (OPSCC), human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is associated with improved prognosis in the curative and R/M settings [5]. p16 protein is a surrogate biomarker for HPV infection in OPSCC (based on correlation of p16 expression with HPV status), with p16 positivity reported in >50% of OPSCC in some countries [5]. Other molecular alterations, including PI3K-pathway components, have been observed in HPV-positive and HPV-negative HNSCC, while EGFR amplification has been exclusively associated with HPV-negative disease [3].

Because afatinib selectively targets ErbB family signaling, as well as the interplay between HPV, the PI3K pathway and ErbB signaling, we were interested in whether expression of specific biomarkers was predictive of clinical benefit with afatinib. This study evaluates the association of prespecified biomarkers with clinical outcomes in LUX-H&N1.

Methods

Study design and patients

LUX-H&N1 (NCT01345682) is a global, phase III trial, which enrolled patients with second-line R/M HNSCC with progression following ≥2 cycles of platinum therapy [1]. Patients were randomized (2 : 1) to oral afatinib (40 mg/day) or intravenous methotrexate (40 mg/m2/week), stratified by Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (ECOG PS; 0/1) and prior EGFR-monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy for R/M disease. The study design and primary analysis have been reported [1].

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and guidelines on Good Clinical Practice. The protocol was approved by local ethics committees at each center. Written informed consent was obtained for each patient, with separate consent obtained from patients who volunteered for inclusion in the biomarker analysis.

Biomarker analysis

Tumor (latest obtained archived tissue) and serum samples were collected from patients at study entry. Tumor biomarker assessments included p16 (prespecified subgroup; all tumor subsites), HER2, PTEN, c-MET and PTEN expression by immunohistochemistry, and EGFR amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization. Assessments were carried out in a central laboratory using full, mounted tissue sections (p16 only) and tissue microarray cores (all other biomarkers). Details for each assay are provided in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. Using a histology (H)-score of ≥210, p16 positivity was determined according to Ang et al. (strong, diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in ≥70% of tumor cells) [6]. As there is no standard definition for EGFR amplification in HNSCC, exploratory thresholds were defined as either extensive high-polyploidy (≥50% of cells with ≥4 copies) or focal amplification (≥1 cell with ≥8 copies) of the EGFR locus [7]. Similarly, as there are no established protein expression thresholds for the other biomarkers analyzed, exploratory H-score cut-offs were used: PTEN >150 (high), HER2 ≤40 (low), HER3 ≤50 (low), c-MET >75 (high). Serum samples were analyzed via the VeriStrat® test (Biodesix, Boulder, CO) [8].

Statistical analyses

Detailed statistical analyses (SAS, v9.2) for LUX-H&N1 have been published [1]. Biomarker analyses included all randomized patients who volunteered for inclusion. PFS/overall survival (OS) for each treatment group within biomarker-defined subgroups was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method; HRs for afatinib versus methotrexate were derived using a stratified Cox proportional hazards model (also used to explore subgroup by treatment interactions). Biomarker subgroups based on p16 and VeriStrat status were prespecified. Each biomarker subgroup was analyzed separately; multiplicity was not adjusted. Exploratory analyses combining prespecified subgroups and biomarkers were also conducted. Due to the limited availability of tissue samples, some biomarker subgroups had small sample sizes.

Results

Patients

Of 483 randomized patients, 326 (67%) provided consent for biomarker analysis (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online); baseline characteristics were representative of the overall population (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Among patients in the tumor biomarker subset (n = 268), 80% (n = 215) had samples from the primary tumor site, with 14% (n = 37) and 4% (n = 11) from regional and distant metastases (tumor site was unavailable for five patients). Among patients with information on both timing of prior cetuximab therapy for R/M disease and tumor biopsy (n = 139), 88% (n = 122) were biopsied before cetuximab initiation.

Individual tumor biomarker analysis

Individual tumor tissue analyses yielded the following profiles for biomarkers of interest: 85% (199/234; all tumor subsites) p16-negative, 52% (112/214) EGFR-amplified, 55% (119/218) HER3-low, 29% (63/221) PTEN-high, 67% (104/156) c-MET-high, and 91% (146/161) HER2-low (Table 1). Of the samples assessed for p16 status, 34% (80/234) were OPSCC, of which the majority (71%; 57/80) were p16-negative; 66% (154/234) were non-OPSCC, of which 8% (12/154) were p16-positive (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). Only 9% (15/161) of samples exhibited HER2-high expression; thus, analyses of outcomes based on HER2 status were not conducted.

Table 1.

Disposition and tumor response in biomarker-defined subgroupsa

| Biomarker | Biomarker subset (n=326) |

Tumor response: afatinib versus methotrexate |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afatinib (n=219) | Methotrexate (n=107) | Percentage of total, n/N (%)b | ORR, n (%) | DCR, n (%) | Duration of response, days (range) | |

| p16-positivec | 23 | 12 | 35/234 (15) | 0 (0) versus 1 (8.3) | 11 (47.8) versus 6 (50.0) | NE versus 83 |

| p16-negativec | 135 | 64 | 199/234 (85) | 19 (14.1) versus 1 (1.6) | 69 (51.1) versus 23 (35.9) | 91 (15–233) versus 35 |

| EGFR amplified | 83 | 29 | 112/214 (52) | 11 (13.3) versus 0 (0) | 43 (51.8) versus 10 (34.5) | 107 (41–233) versus NE |

| EGFR not amplified | 67 | 35 | 102/214 (48) | 3 (4.5) versus 0 (0) | 28 (41.8) versus 16 (45.7) | 82 (43–83) versus NE |

| HER3 (H-score ≤50) | 83 | 36 | 119/218 (55) | 9 (10.8) versus 1 (2.8) | 45 (54.2) versus 15 (41.7) | 85 (36–295) versus 83 |

| HER3 (H-score >50) | 67 | 32 | 99/218 (45) | 6 (9.0) versus 0 (0) | 27 (40.3) versus 14 (43.8) | 95 (41–197) versus NE |

| PTEN (H-score ≤150) | 108 | 50 | 158/221 (71) | 14 (13.0) versus 1 (2.0) | 58 (53.7) versus 25 (50.0) | 70 (36–295) versus 83 |

| PTEN (H-score >150) | 43 | 20 | 63/221 (29) | 3 (7.0) versus 0 (0) | 17 (39.5) versus 5 (25.0) | 170 (82–197) versus NE |

| c-MET (H-score ≤75) | 38 | 14 | 52/156 (33) | 3 (7.9) versus 0 (0) | 14 (36.8) versus 4 (28.6) | 42 (36–170) versus NE |

| c-MET (H-score >75) | 73 | 31 | 104/156 (67) | 10 (13.7) versus 0 (0) | 39 (53.4) versus 17 (54.8) | 96 (41–197) versus NE |

| VeriStrat: good | 127d | 70 | 197/303 (65) | 15 (11.8) versus 3 (4.3) | 64 (50.4) versus 30 (43.5) | 120 (36–295) versus 142 (83–144) |

| VeriStrat: poor | 69 | 35 | 104/303 (34) | 7 (10.0) versus 1 (2.9) | 24 (34.3) versus 12 (34.3) | 82 (15–113) versus 35 |

In the analysis of HER2 status, 146/161 (91%) patients were reported as HER2 ≤40, and 15/161 (9%) of patients were HER2 >40. Due to the small number of patients with HER2-high expression, further outcomes analyses were not conducted.

Percentage based on total patients with specific biomarker available.

Based on central test results; includes tumors from all subsites (oropharyngeal and non-oropharyngeal).

VeriStrat status was indeterminate for two patients.

DCR, disease control rate; H-score, histology-score; NE, not estimable; ORR, objective response rate.

Objective response rates (ORR) were improved with afatinib versus methotrexate in all biomarker subgroups, with the exception of patients with p16-positive disease (n = 35, all tumor subsites; Table 1). Disease control rates (DCRs) were improved with afatinib in patients with p16-negative, EGFR-amplified, HER3-low, PTEN-high or c-MET-low disease. Notable improvements in the percentage of patients experiencing Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST, v1.1) partial response (i.e. >30% tumor shrinkage from baseline) with afatinib versus methotrexate were reported in those with p16-negative (22% versus 2%) and EGFR-amplified tumors (21% versus 0%; supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

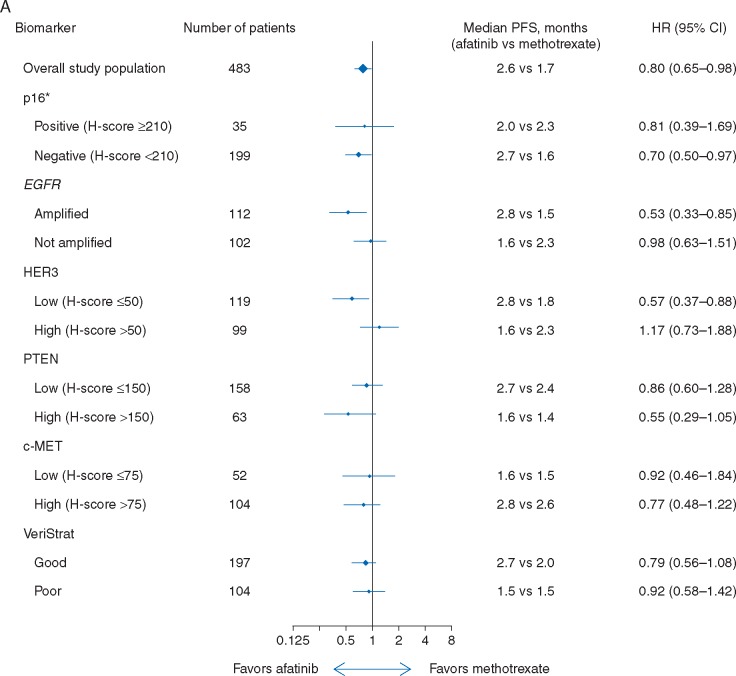

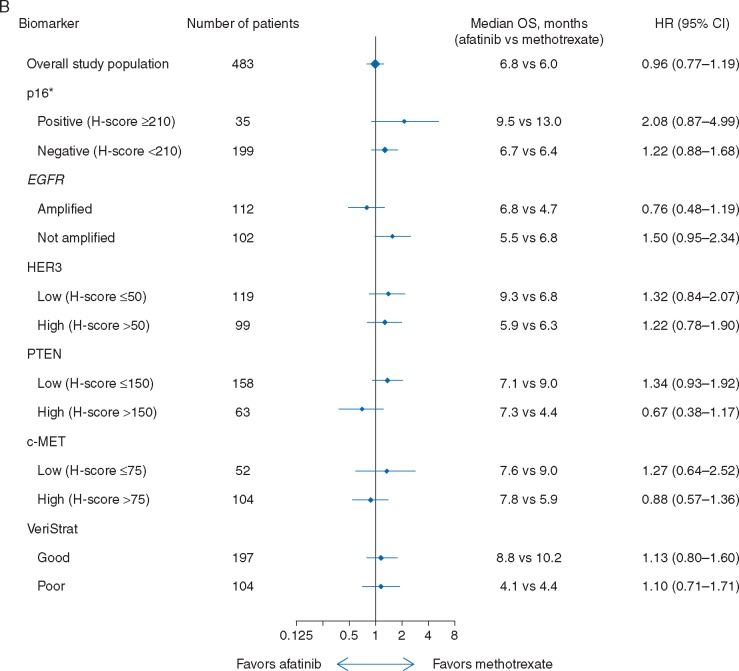

Improvements in median PFS were observed with afatinib versus methotrexate in patients with p16-negative [all tumor subsites; 2.7 versus 1.6 months; HR 0.70 (95% CI 0.50–0.97)], EGFR-amplified [2.8 versus 1.5 months; HR 0.53 (0.33–0.85)], or HER3-low [2.8 versus 1.8 months; HR 0.57 (0.37–0.88)] disease, with a trend towards improvement observed in patients with PTEN-high tumors [1.6 versus 1.4 months; HR 0.55 (0.29–1.05); Figure 1A]. No difference in PFS between treatment groups was observed in either c-MET subgroup. A trend toward improved OS with afatinib was observed in patients with EGFR-amplified [6.8 versus 4.7 months; HR 0.76 (0.48–1.19)] or PTEN-high disease [7.3 versus 4.4 months; HR 0.67 (0.38–1.17); Figure 1B]. Survival outcomes in patients with p16-negative or p16-positive tumors were generally consistent when analyzed according to primary tumor site (OPSCC and non-OPSCC), with longer median OS observed in patients with p16-positive versus p16-negative disease, irrespective of treatment (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Figure 1.

PFS (A) and OS (B) according to biomarker-defined subgroups. *Based on central test results; includes tumors from all subsites (oropharyngeal and non-oropharyngeal). CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

Combined tumor biomarker analysis

Because EGFR amplification has been associated with p16-negativity in HNSCC, combined analysis of these two biomarkers (all tumor subsites) was conducted. In patients with combined p16-negative and EGFR-amplified HNSCC, significant improvement in PFS with afatinib versus methotrexate was observed [2.7 versus 1.5 months; HR 0.47 (0.28–0.80)], with 29% of afatinib-treated patients achieving partial response (Table 2; supplementary Figure S3A, available at Annals of Oncology online). A trend toward improved OS was also observed in this subset [6.8 versus 4.7 months; HR 0.77 (0.47–1.26); Table 2]. No improvement in PFS or OS was observed in the subset of patients with p16-negative HNSCC without EGFR amplification.

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes in combined subgroups of patients with p16-negative diseasea

| p16-negative combined subgroups |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EGFR amplified |

EGFR not amplified |

EGFR mAb naïve |

EGFR mAb pretreated |

|||||

| Outcome | Afatinib (n=62) | MTX (n=26) | Afatinib (n=49) | MTX (n=23) | Afatinib (n=51) | MTX (n=21) | Afatinib (n=84) | MTX (n=43) |

| Median PFS, months | 2.7 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 1.5 |

| HR (95% CI) | 0.47 (0.28–0.80) | 1.05 (0.61–1.82) | 0.55 (0.31–0.98) | 0.86 (0.58–1.29) | ||||

| Median OS, months | 6.8 | 4.7 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 8.0 | 10.3 | 6.3 | 5.5 |

| HR (95% CI) | 0.77 (0.47–1.26) | 1.49 (0.86–2.56) | 1.67 (0.92–3.02) | 1.01 (0.68–1.49) | ||||

| ORR, % | 17.7 | 0 | 6.1 | 0 | 27.5 | 4.8 | 6.0 | 0 |

| DCR, % | 53.2 | 30.8 | 44.9 | 52.2 | 72.6 | 42.9 | 38.1 | 32.6 |

Data not shown in combined p16 positive subgroups due to consistently small numbers.

CI, confidence interval; DCR, disease control rate; HR, hazard ratio; mAb, monoclonal antibody; ORR, objective response rate; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival.

In the primary analysis, improved PFS with afatinib was observed in a prespecified subgroup of patients with p16-negative disease and those who were EGFR mAb naïve [1]. Here, we further analyzed outcomes in a combined subset of patients with p16-negative tumors who were also EGFR mAb naïve, demonstrating notable improvement in PFS [4.0 versus 2.4 months; HR 0.55 (0.31–0.98)] with afatinib versus methotrexate, with 38% of afatinib-treated patients experiencing partial response (Table 2; supplementary Figure S3B, available at Annals of Oncology online).

VeriStrat analysis

Of 303 patients with available serum samples, 65% were classified as VeriStrat ‘Good’ (Table 1). VeriStrat status did not appear to impact PFS or OS outcomes with afatinib versus methotrexate (Figure 1A and B); however, VeriStrat was prognostic of PFS and OS in afatinib-treated patients [PFS: 2.7 versus 1.5 months; HR 0.71 (0.49–0.94); OS: 8.8 versus 4.1 months; HR 0.46 (0.33–0.64)] and OS in methotrexate-treated patients [OS: 10.2 versus 4.4 months; HR 0.40 (0.24–0.69); supplementary Figure S4, available at Annals of Oncology online]. Consistent with the overall study results, ORR was improved with afatinib versus methotrexate in both VeriStrat subgroups; DCR was improved with afatinib in the VeriStrat ‘Good’ subgroup (Table 1). Outcomes based on VeriStrat status were independent of other tumor biomarkers and subsite (data on file).

Discussion

In this analysis of LUX-H&N1, subgroups of R/M HNSCC patients with p16-negative, EGFR-amplified, HER3-low or PTEN-high tumors achieved increased PFS benefit with second-line afatinib versus methotrexate. VeriStrat appeared to be prognostic but not predictive of differential benefit for either treatment group. In the primary study analysis, improvement in PFS but not OS was more pronounced with afatinib versus methotrexate in a prespecified subgroup with p16-negative disease (HR 0.69) [1]; these findings are consistent with results based on p16-status in the current analysis. Most samples in this study were defined as p16-negative (85%), which is consistent with previous reports in HNSCC of mixed primary tumor site [9]. The small number of p16-positive samples in this study limited the statistical power of analysis in these patients. Outcomes with EGFR mAbs in patients with HNSCC based on p16 status have been inconclusive, with variable activity observed with panitumumab or cetuximab plus chemotherapy, and cetuximab plus radiotherapy in p16-negative or-positive disease [10–12]. These outcomes may have been influenced by different definitions of p16 positivity, interactions with the combination treatment (cytotoxic chemotherapy), differences among the EGFR mAbs themselves, and the inherent variable activity of EGFR mAbs against HNSCC. In analyses of patients with p16-negative HNSCC according to prior treatment with EGFR mAb therapy, more pronounced improvements in PFS and tumor response were observed with afatinib in those who were EGFR mAb naïve versus mAb pretreated, consistent with findings in the overall population [1]. Although a previous phase II study in R/M HNSCC suggested a lack of cross-resistance between afatinib and cetuximab [13], the current findings suggest that afatinib is more effective in patients whose tumors are cetuximab naïve.

More pronounced benefit with afatinib was also observed in patients with EGFR-amplified tumors, consistent with afatinib’s mechanism of action. In previous studies, EGFR gene copy number was not predictive of survival outcomes with gefitinib monotherapy or cetuximab plus chemotherapy in R/M HNSCC, although greater response was observed with gefitinib in tumors with higher versus lower copy number [14, 15]. These findings may reflect both the lack of an established definition for EGFR amplification and the generally lower activity of gefitinib in HNSCC. In lung cancer, also characterized by EGFR gene copy number variability, amplification is defined by either focal amplification or extensive polyploidy [7]. Adopting a similar definition here, EGFR amplification frequency was 52%, within the range of previous reports [14, 15]. Association of EGFR amplification with improved outcomes with afatinib may result from afatinib’s broader mechanism of action compared with gefitinib and cetuximab, although the impact of chemotherapy in prior cetuximab studies should also be considered. Even more pronounced improvements in PFS and tumor response were observed with afatinib versus methotrexate in patients with combined p16-negative and EGFR-amplified disease.

More pronounced afatinib activity was also observed in HER3-low tumors, although three patients with HER3-high expressing tumors did demonstrate complete responses (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). The implications of this finding are not clear given the very small number of cases. While studies suggest association between HER3 overexpression and poor prognosis in HNSCC (including HPV-positive disease), to our knowledge there is no evidence for HER3 as a predictive biomarker, and a validated cut-off for HER3 overexpression has not been established [16, 17]. We defined an exploratory H-score of ≤50 (membranous staining) as HER3-low, representing 55% of samples. With more than six PI3K binding sites, HER3 is a potent activator of the PI3K pathway; however, because HER3 is a kinase-inactive receptor, heterodimerization with other ErbB family members is required for signaling (supplementary Figure S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). In contrast to HER3, PTEN is a negative regulator of the PI3K pathway, and loss of PTEN has been associated with PI3K-pathway activation. In this analysis, 29% of samples were identified as PTEN-high (defined as H-score >150; cytoplasmic staining), in contrast to previous studies wherein PTEN-low (or null) samples were reported in ∼30% of cases; this is potentially due to prior exposure to cetuximab or to different methodologies and expression thresholds (10% cut-off for PTEN-positive stained cells [18] or automated quantitative analysis cut-off of 570 [19]). PTEN-high expression was generally associated with poorer outcomes irrespective of treatment in this study; however, among patients with tumors with high PTEN expression benefit was more pronounced for those receiving afatinib versus methotrexate. More pronounced afatinib activity was also observed in HER3-low tumors. PTEN-high and HER3-low possibly reflect low intrinsic PI3K-pathway activity suggesting that constitutive PI3K-pathway activation may antagonize the activity of afatinib, although this hypothesis requires further study.

There are some limitations to this analysis, which should be considered. Firstly, biomarker analyses included mostly archived tissue and, due to optional tissue/serum sampling, consisted of ∼67% of the study population, resulting in limited sample sizes for some subgroups. In addition, tumor samples were collected from both primary tumor and metastatic sites, and at different time points relative to study entry. Furthermore, the use of tissue microarray for analysis may not be representative of results obtained from larger tissue sections. With regards to the biomarker assessment methodology, the lack of established definitions for gene amplification and protein expression in HNSCC resulted in utilization of exploratory cut-offs, limiting the ability to compare our findings with similar studies. Further, while this analysis defined p16 status across all tumor subsites, use of p16 as a surrogate for HPV infection is most firmly validated in OPSCC.

In summary, this exploratory biomarker analysis of second-line R/M HNSCC in LUX-H&N1 preliminarily identified subgroups of patients with tumors reflecting alterations in p16 expression (p16-negative), and ErbB- and PI3K-pathway dysregulation (EGFR-amplified, HER3-low, PTEN-high), who may achieve increased benefit with afatinib versus methotrexate. Other ErbB-targeted agents, including lapatinib (an EGFR/HER2 inhibitor) and duligotuzumab (an EGFR/HER3 monoclonal antibody), have demonstrated limited activity in HNSCC [20, 21]. Further analysis of identified subgroups may help guide the optimal future application of these agents. Future studies are warranted to define assessment methodologies for these biomarkers, including relevance of the cut-offs, and provide more robust analyses of biomarker association with clinical outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients, their families, and all of the investigators who participated in the study. We would also like to thank Liz Svensson (Boehringer Ingelheim) for her contributions to the study. We were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, were involved at all stages of manuscript development, and have approved the final version.

Funding

This work was supported by Boehringer Ingelheim. Medical writing assistance, supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim, was provided by Katie Dean, PhD, of GeoMed, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, during the preparation of this manuscript. There is no applicable grant number for this work.

Disclosure

EEWC reports acting in a consulting or advisory role for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Merck, and Novartis, and has participated in speakers’ bureaus for Bayer and Eisai. LFL has participated in advisory boards for Eisai, Bristol-Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Lilly, Merck Serono, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Debiopharm, VentiRX, SOBI, Novartis, AstraZeneca and Bayer. BB reports receiving advisory fees from Merck and research funding from Merck, Advaxis, and Innate Pharma. JF has received honoraria from AstraZeneca and Bristol Myers Squibb. TG has received honoraria and participated on advisory boards for Boehringer Ingelheim and Merck Serono. JV has received honoraria and participated on advisory boards for Merck, Amgen, Innate Pharma, PCI Biotech, Synthon, and Biopharmaceuticals. MT has received lecture fees from Merck Serono and research funding from AstraZeneca, MSD, Ono Pharmaceutical, and Bayer. JG has participated in advisory boards for BMS and Merck Serono, and has received research grants from BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chugai, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Merck Serono and Sanofi. ND owns stock in and is employed by Biodesix, Inc. NK, XJC, NG, FS, and EE are all employees of Boehringer Ingelheim. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Machiels JP, Haddad RI, Fayette J. et al. Afatinib versus methotrexate as second-line treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck progressing on or after platinum-based therapy (LUX-Head & Neck 1): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 583–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Price KA, Cohen EE.. Mechanisms of and therapeutic approaches for overcoming resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeted therapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SCCHN). Oral Oncol 2015; 51: 399–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cancer Genome Atlas Network. Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature 2015; 517: 576–582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takikita M, Xie R, Chung JY. et al. Membranous expression of Her3 is associated with a decreased survival in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Transl Med 2011; 9: 126.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deng Z, Hasegawa M, Aoki K. et al. A comprehensive evaluation of human papillomavirus positive status and p16INK4a overexpression as a prognostic biomarker in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol 2014; 45: 67–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eichler AF, Kahle KT, Wang DL. et al. EGFR mutation status and survival after diagnosis of brain metastasis in nonsmall cell lung cancer. Neuro Oncol 2010; 12: 1193–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cappuzzo F, Hirsch FR, Rossi E. et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene and protein and gefitinib sensitivity in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005; 97: 643–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gregorc V, Novello S, Lazzari C. et al. Predictive value of a proteomic signature in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with second-line erlotinib or chemotherapy (PROSE): a biomarker-stratified, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: 713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gronhoj Larsen C, Gyldenlove M, Jensen DH. et al. Correlation between human papillomavirus and p16 overexpression in oropharyngeal tumours: a systematic review. Br J Cancer 2014; 110: 1587–1594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rosenthal DI, Harari PM, Giralt J. et al. Association of human papillomavirus and p16 status with outcomes in the IMCL-9815 phase III registration trial for patients with locoregionally advanced oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck treated with radiotherapy with or without cetuximab. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 1300–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vermorken JB, Psyrri A, Mesia R. et al. Impact of tumor HPV status on outcome in patients with recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck receiving chemotherapy with or without cetuximab: retrospective analysis of the phase III EXTREME trial. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 801–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vermorken JB, Stohlmacher-Williams J, Davidenko I. et al. Cisplatin and fluorouracil with or without panitumumab in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck (SPECTRUM): an open-label phase 3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2013; 14: 697–710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Seiwert TY, Fayette J, Cupissol D. et al. A randomized, phase 2 study of afatinib versus cetuximab in metastatic or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 1813–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Licitra L, Mesia R, Rivera F. et al. Evaluation of EGFR gene copy number as a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of cetuximab in combination with chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: EXTREME study. Ann Oncol 2011; 22: 1078–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Stewart JS, Cohen EE, Licitra L. et al. Phase III study of gefitinib compared with intravenous methotrexate for recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck [corrected]. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 1864–1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Qian G, Jiang N, Wang D. et al. Heregulin and HER3 are prognostic biomarkers in oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer 2015; 121: 3600–3611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brand TM, Hartmann S, Bhola NE. et al. Human papillomavirus regulates HER3 expression in head and neck cancer: implications for targeted HER3 therapy in HPV + patients. Clin Cancer Res 2017; 23: 3072–3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 18. Squarize CH, Castilho RM, Abrahao AC. et al. PTEN deficiency contributes to the development and progression of head and neck cancer. Neoplasia 2013; 15: 461–471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Burtness B, Lee J-W, Yang D. et al. Activity of cetuximab (C) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) patients (pts) with PTEN loss or PIK3CA mutation treated on E5397, a phase III trial of cisplatin (CDDP) with placebo (P) or C. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31(15 suppl): 6028. [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Souza JA, Davis DW, Zhang Y. et al. A phase II study of lapatinib in recurrent/metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res 2012; 18: 2336–2343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Fayette J, Wirth L, Oprean C. et al. Randomized phase II study of duligotuzumab (MEHD7945A) vs. cetuximab in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (MEHGAN Study). Front Oncol 2016; 6: 232.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.