Abstract

Background

Primary analysis of the double-blind, phase III Efficacy of XL184 (Cabozantinib) in Advanced Medullary Thyroid Cancer (EXAM) trial demonstrated significant improvement in progression-free survival with cabozantinib versus placebo in patients with progressive medullary thyroid cancer (MTC). Final analysis of overall survival (OS), a key secondary endpoint, was carried out after long-term follow-up.

Patients and methods

EXAM compared cabozantinib with placebo in 330 patients with documented radiographic progression of metastatic MTC. Patients were randomized (2:1) to cabozantinib (140 mg/day) or placebo. Final OS and updated safety data are reported.

Results

Minimum follow-up was 42 months. Kaplan–Meier analysis showed a 5.5-month increase in median OS with cabozantinib versus placebo (26.6 versus 21.1 months) although the difference did not reach statistical significance [stratified hazard ratio (HR), 0.85; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.64–1.12; P = 0.24]. In an exploratory assessment of OS, progression-free survival, and objective response rate, cabozantinib appeared to have a larger treatment effect in patients with RET M918T mutation–positive tumors compared with patients not harboring this mutation. For patients with RET M918T-positive disease, median OS was 44.3 months for cabozantinib versus 18.9 months for placebo [HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.38–0.94; P = 0.03 (not adjusted for multiple subgroup analyses)], with corresponding values of 20.2 versus 21.5 months (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.70–1.82; P = 0.63) in the RET M918T–negative subgroup. Median treatment duration was 10.8 months with cabozantinib and 3.4 months with placebo. The safety profile for cabozantinib remained consistent with that of the primary analysis.

Conclusion

The secondary end point was not met in this final OS analysis from the trial of cabozantinib in patients with metastatic, radiographically progressive MTC. A statistically nonsignificant increase in OS was observed for cabozantinib compared with placebo. Exploratory analyses suggest that patients with RET M918T–positive tumors may experience a greater treatment benefit with cabozantinib.

Trial Registration Number

Keywords: cabozantinib, medullary thyroid cancer, progression-free survival, overall survival, RET M918T

Introduction

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) is a rare malignancy arising from calcitonin-producing parafollicular C cells of the thyroid gland [1, 2]. MTC accounts for ∼2% of all thyroid carcinomas and up to 14% of thyroid cancer–related deaths. About half of patients with MTC present with lymph node metastases and 10% with distant metastatic disease [3]. Survival rates vary according to disease stage [3]. The 10-year survival rate is 96% for patients with tumors confined to the thyroid gland but only 40% for those with distant metastases [2].

Approximately 75% of cases of MTC occur sporadically, whereas 25% are associated with one of two inherited autosomal dominant syndromes—multiple endocrine neoplasia 2 A (MEN2A) or MEN2B [3, 4]. A number of mutations and signaling pathways have been implicated in MTC pathogenesis. Nearly all patients with hereditary forms have germline mutations identified in the gene encoding the RET protein [5], and somatic RET mutations have been reported in up to 65% of patients with sporadic disease [6–8]. About half of all somatic RET mutations are the M918T point mutation, which is associated with poor prognosis [8, 9]. In patients with sporadic MTC lacking RET mutations, RAS gene mutations are common, occurring in up to 68% of cases [7, 10, 11]. In addition, the vascular endothelial growth factor and MET pathways are thought to promote angiogenesis, invasion, and metastasis in MTC [3, 12, 13].

Chemotherapy has limited activity in patients with unresectable or metastatic MTC [3]. More recently, multitargeted kinase inhibitors (MKIs) have been approved for locally advanced or metastatic MTC [6, 14].

Cabozantinib, an inhibitor of kinases, including MET, vascular endothelial growth factor receptors, and RET [15], is approved in the United States and Europe for progressive, metastatic MTC based on findings of the EXAM trial (Trial Registration Number: NCT00704730) [14]. In this phase III study, cabozantinib significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS), the primary end point, compared with placebo in patients with documented radiographic progression of metastatic MTC (estimated median PFS 11.2 versus 4.0 months; hazard ratio [HR], 0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.19–0.40; P < 0.001) [14]. At the primary analysis, a planned interim analysis of OS showed no difference between treatment arms (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.63–1.52), but only 96 of the planned 217 deaths for the final analysis had occurred.

We report here the final OS analysis for the EXAM trial after additional follow-up and include updated safety data after long-term treatment with cabozantinib.

Patients and methods

Study design and patients

The EXAM study design has been described previously [14]. In brief, EXAM was an international, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase III study evaluating cabozantinib in adult patients with unresectable locally advanced or metastatic MTC. Patients were required to have documented radiographic disease progression per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors guidelines version 1.0 at screening compared with images obtained within the prior 14 months. No limit was placed on number of prior therapies, including MKIs. All patients provided written informed consent. The protocol was approved by ethics committees or institutional boards at each clinical site, nationally, or both.

The primary end point was PFS [14]. Key secondary end points were objective response rate (ORR), OS, and assessment of the relationship between RET mutation status and efficacy of cabozantinib [14]. Mutations in the RET gene (exons 10, 11, and 13–16) were identified from blood and archival tumor samples using Sanger and next-generation sequencing methods [14, 16], and a subset of tumor samples not harboring RET mutations was also analyzed for mutations in HRAS, KRAS, and NRAS at codons 12, 13, and 61 [14, 16].

Randomization and treatment

Patients were randomized to receive cabozantinib or placebo (2:1) stratified by age (≤65 and >65 years) and prior MKI treatment (yes, no) [14]. Patients received cabozantinib (140 mg/day) or placebo administered orally until intolerable toxicity or disease progression per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.0. The study was unblinded after the primary analysis of PFS. Patients receiving placebo were not allowed to crossover to cabozantinib.

Overall survival analysis

An interim OS analysis was planned at the time of the primary PFS analysis. The final OS analysis was to be conducted after at least 217 deaths were observed in the intent-to-treat population. This provided 80% power to detect an HR of 0.667 using the log-rank test and a 2-sided significance level of 4% (allocated at interim and final analyses per an alpha spending function), corresponding to a 33.3% reduction in rate of death or a 50% increase in median survival from 22 to 33 months.

Median OS was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. For patients who were alive at the time of data cutoff for the current analysis (28 August 2014) or who were lost to follow-up, the duration of OS was right censored at the date the patient was last known to be alive. Testing between the two treatment arms was carried out by the stratified log-rank test using randomization stratification factors. The HR was estimated using a Cox regression model with treatment group as the main effect and included the randomization stratification factors. In an exploratory subgroup analysis, we assessed OS and PFS by baseline demographics and characteristics, and RET and RAS mutation status. Analyses on the basis of RET mutation status were pre-specified (RET mutation–positive, RET mutation–negative, and RET mutation–unknown subgroups), while analyses based on RAS mutation status or the presence of the RET M918T mutation were post hoc. The primary analysis data cut-off of 6 April 2011 was used for all PFS analyses. Calculated P values for subgroups are descriptive only.

Safety analysis

Safety assessments included evaluation of adverse events (AEs), serious AEs (SAEs), deaths, standard laboratory tests, physical examinations, and electrocardiograms. Severity of AEs was based on National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 3. SAEs were defined in accordance with International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Clinical Safety Data Management (1994).

Results

Patients

At data cut-off (28 August 2014), 10% (21/219) of patients in the cabozantinib group were still receiving treatment; all patients in the placebo group had discontinued (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Detailed baseline characteristics of the randomized patients were balanced between arms [14]. Briefly, 40% of all patients (n = 133) had received prior anticancer therapy, and 21% (n = 68) prior MKI treatment. One quarter (25%) of patients (n = 83) had received ≥2 systemic therapies. The main sites of metastases were lymph nodes, liver, lung, and bone. RET and RAS mutational status are summarized in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. Apart from mutational status, RET subgroups showed similar baseline characteristics (supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

OS and PFS

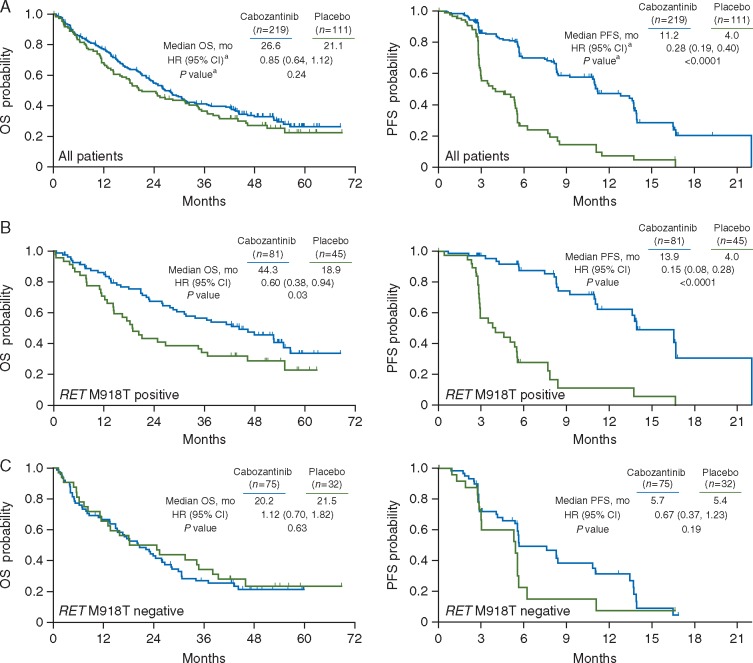

In this OS analysis, 64% (141/219) of patients in the cabozantinib arm and 69% (77/111) in the placebo arm had died. Minimum follow-up was 42 months. There was a 5.5-month numerical increase in median OS with cabozantinib versus placebo (26.6 versus 21.1 months). However, this difference did not reach statistical significance (stratified HR, 0.85; 95% CI, 0.64–1.12; P = 0.24) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curve of overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) in the (A) overall intent-to-treat population, (B) in patients with RET M918T–positive disease, and (C) in patients with RET M918T–negative disease. Data cut-off was 28 August 2014 for OS and 6 April 2011 for PFS. aAnalyses for (A) were stratified by randomization stratification factors, and analyses of subgroups (B and C) were unstratified. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Methods for determining RET M918T status are described elsewhere [16].

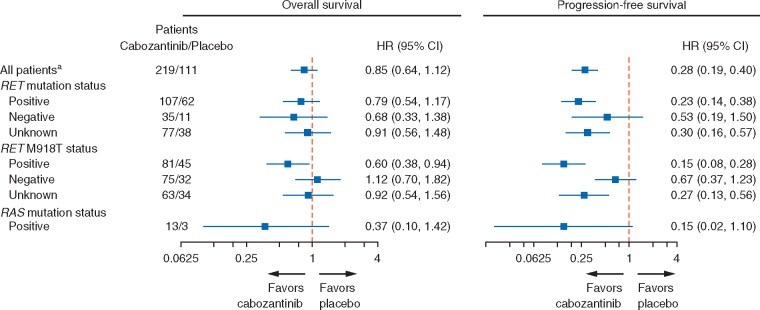

OS and PFS data were assessed in subgroups, including RET mutation status, RET M918T mutation status, and RAS mutation status (Figures 1B and C and 2), as well as demographics and baseline characteristics (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Cabozantinib was favored over placebo for both OS and PFS in patients with and without RET mutations and for those with an unknown RET mutation status. There was a substantial OS benefit associated with cabozantinib in the RET M918T–positive subgroup with a median OS of 44.3 versus 18.9 months for placebo [HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.38–0.94; P = 0.03 (not adjusted for multiple subgroup analyses)]. PFS in the RET M918T–positive subgroup were consistent with OS, favoring cabozantinib (HR, 0.15; 95% CI 0.08–0.28; P <0.0001). For the RET M918T–negative subgroup, there was no OS benefit with cabozantinib (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 0.70–1.82; P = 0.63), whereas there was a trend toward improved PFS that did not reach statistical significance (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.37–1.23; P = 0.19). At the time of the primary analysis (cut-off of 6 April 2011), the ORR for patients receiving cabozantinib was 28% overall, 34% for the RET M918T–positive subgroup, and 20% for the RET M918T–negative subgroup. There were no responses in the placebo arm.

Figure 2.

Subgroup analysis of overall survival and progression-free survival (PFS) according to RET mutation status, RET M918T status, and RAS mutations status. Data cut-off was 28 August 2014 for overall survival and 6 April 2011 for PFS. aAnalyses for all patients were stratified by randomization stratification factors, and analyses of subgroups were unstratified. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval. Methods for determining RET and RAS mutation status are described elsewhere [16].

Subgroup analysis of patients harboring RAS mutations showed a trend toward improved OS (HR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.10–1.42) and PFS (HR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.02–1.10). However, this was a small subgroup (13 patients in the cabozantinib arm and three in the placebo arm) and differences between arms were not statistically significant.

Subsequent anticancer therapy

The percentage of patients who received any subsequent anticancer therapy was 44% (32% systemic therapy) in the cabozantinib group and 58% (50% systemic therapy) in the placebo group (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online). MKIs were frequently used as subsequent systemic therapy (27% in the cabozantinib group, 41% in the placebo group). For patients receiving subsequent therapy, there was no OS benefit with cabozantinib versus placebo (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.63–1.39), while cabozantinib was favored in patients who did not receive subsequent therapy (HR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.39–0.88) (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Safety

Median duration of exposure to cabozantinib was 10.8 months (interquartile range, 3.3–25.1 months) with 25% receiving cabozantinib for >2 years. This was more than three times that of the placebo arm (median 3.4 months; interquartile range, 3.0–6.5 months). The proportion of cabozantinib-treated patients who had a dose reduction was 82%, and 46% underwent a second-level dose reduction.

Safety data have been updated through the 28 August 2014 cut-off. AEs reported in ≥20% of patients are summarized in Table 1 (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online for AEs reported in ≥10%). The types and rates of AEs in this updated analysis remained consistent with the PFS analysis [14]. The most frequently reported SAEs (≥2%) in the cabozantinib arm were pneumonia (4.2% versus 3.7% in the placebo arm), pulmonary embolism (3.3% versus 0%), hypocalcemia (2.8% versus 0%), mucosal inflammation (2.8% versus 0%), dehydration (2.3% versus 0.9%), dysphagia (2.3% versus 1.8%), hypertension (2.3% versus 0%), and lung abscess (2.3% versus 0%).

Table 1.

Adverse events occurring in ≥20% of cabozantinib-treated patients regardless of causality by maximum severity reporting

| Cabozantinib | Placebo | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

N = 214 |

N = 109 |

|||

| Grade, n (%) |

Grade, n (%) |

|||

| All | ≥3 | All | ≥3 | |

| Diarrhea | 150 (70.1) | 46 (21.5) | 39 (35.8) | 2 (1.8) |

| Weight decreased | 124 (57.9) | 21 (9.8) | 12 (11.0) | 0 |

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome | 113 (52.8) | 27 (12.6) | 2 (1.8) | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 105 (49.1) | 15 (7.0) | 17 (15.6) | 1 (0.9) |

| Nausea | 100 (46.7) | 4 (1.9) | 23 (21.1) | 0 |

| Fatigue | 91 (42.5) | 21 (9.8) | 33 (30.3) | 3 (2.8) |

| Dysgeusia | 75 (35.0) | 1 (0.5) | 6 (5.5) | 0 |

| Hair color changes | 73 (34.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Hypertension | 70 (32.7) | 19 (8.9) | 5 (4.6) | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 64 (29.9) | 5 (2.3) | 3 (2.8) | 0 |

| Constipation | 60 (28.0) | 0 | 6 (5.5) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 56 (26.2) | 5 (2.3) | 2 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) |

| Mucosal inflammation | 54 (25.2) | 7 (3.3) | 4 (3.7) | 0 |

| Asthenia | 53 (24.8) | 14 (6.5) | 16 (14.7) | 2 (1.8) |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 52 (24.3) | 11 (5.1) | 6 (5.5) | 2 (1.8) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 51 (23.8) | 4 (1.9) | 6 (5.5) | 0 |

| Hypocalcemia | 51 (23.8) | 23 (10.7) | 5 (4.6) | 0 |

| Rash | 49 (22.9) | 2 (0.9) | 11 (10.1) | 0 |

| Back pain | 47 (22.0) | 9 (4.2) | 16 (14.7) | 1 (0.9) |

| Dysphonia | 47 (22.0) | 0 | 11 (10.1) | 0 |

| Abdominal pain | 47 (22.0) | 7 (3.3) | 8 (7.3) | 1 (0.9) |

| Pain in extremity | 45 (21.0) | 4 (1.9) | 13 (11.9) | 1 (0.9) |

| Dry skin | 43 (20.1) | 0 | 3 (2.8) | 0 |

Grade 5 AEs that occurred before the 15 June 2011 data cut-off were reported in the primary analysis [14]. During the additional follow-up, six patients in the cabozantinib arm died while on study treatment or within 30 days of the last dose. One of these was considered related to study treatment (esophageal bleeding for a patient on treatment for 381 days). The other grade 5 AEs were considered unrelated to treatment and included multiorgan failure (one patient on treatment for 542 days), bronchopneumonia (one patient on treatment for 705 days), general physical health deterioration (two patients on treatment for 674 and 1324 days), and respiratory failure (one patient on treatment for 785 days).

Discussion

In this updated analysis of the phase III EXAM trial in patients with progressive, metastatic MTC, the secondary end point of improved OS was not reached. Median OS was 5.5 months longer with cabozantinib versus placebo, but this did not achieve statistical significance. In exploratory analyses of OS, PFS, and ORR, cabozantinib appeared to be more active in patients who were RET M918T positive than in those who were RET M918T negative. For RET M918T–positive patients, median OS was 44.3 months for cabozantinib versus 18.9 months for placebo.

In the primary analysis of this trial, the primary end point of improved PFS was met. Median PFS with cabozantinib was 11.2 months compared with 4.0 months for placebo (HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.19–0.40; P <0.001) [14]. RET M918T–positive patients had longer PFS and higher ORR versus RET M918T–negative patients. OS results appear to be consistent with PFS but are limited because of the sample size. The trial was designed with reasonable power (80%) for OS as a secondary end point provided that cabozantinib treatment resulted in a large benefit (50% increase) based on study size. Because MTC is relatively rare, the feasibility of designing a trial assuming a more modest but clinically relevant OS benefit is not practical. In addition, the use of subsequent systemic anticancer therapy (38% of patients in the cabozantinib arm versus 50% of patients in the placebo arm) may also have impacted the OS results.

The OS findings in patients harboring an RET M918T mutation are of clinical interest although these are exploratory data. RET M918T has been associated with poorer prognosis for patients with sporadic disease and the most rapid course of disease development for patients with hereditary disease [8, 9]. The mechanisms by which patients with RET M918T–positive tumors would respond better to cabozantinib than those with RET M918T–negative tumors have not been characterized. However, cabozantinib’s mechanism of action and the biochemical impact of the RET M918T mutation provide insight into the potential etiology. Possible contributing factors include the effects of the mutation of RET signaling, and its sensitivity to inhibition by cabozantinib. The M918T mutation in the RET kinase domain has been shown to increase its catalytic activity [17]. Differences in downstream signaling between RET M918T and other RET isoforms have also been noted [18, 19], including enhanced activation of the RAS signaling pathway. The high catalytic activity of the M918T isoform and its strong ability to activate signaling in crucial downstream pathways may promote higher ‘oncogene addiction’ to RET and greater sensitivity to RET inhibition [20]. Cabozantinib is a potent inhibitor of RET, including the wild-type and M918T isoforms [21].

In contrast to the cabozantinib arm, the difference in OS between RET M918T–positive and RET M918T–negative patients who were randomized to the placebo arm was less notable (<3 months) despite previously reported association of RET M918T with poor prognosis [8, 9]. This may be attributable to all patients in the EXAM study having advanced progressive disease at study entry.

The results of this current analysis suggest that identification of tumors bearing somatic RET M918T mutations may be a predictive biomarker for progressive MTC, but this will require confirmation and validation. Further, determination of RET mutational status in the clinical setting presents challenges. There are technical limitations to sequencing, and mutations may be present in only some lesions or at later disease stages [22]. Given these caveats and the activity of cabozantinib in the RET M918T–negative group with respect to PFS and ORR, patients with progressive MTC should not be excluded from cabozantinib treatment based solely on tumor genotype.

There were no new or unexpected signals in the updated safety data for patients treated with cabozantinib, some of whom remained on treatment for extended periods—25% of patients received cabozantinib for >2 years [14]. The majority of patients underwent dose reductions, suggesting that with appropriate dose reductions and AE management, patients can maintain long-term treatment with cabozantinib. The study of cabozantinib in MTC is continuing, including a trial comparing the 140-mg starting dose in capsules to a 60-mg starting dose in tablets (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01896479). This study will also evaluate the relationship of RET M918T status with clinical activity.

In conclusion, in this final analysis of OS from the EXAM trial, the secondary end point of OS was not met. A statistically non-significant increase in OS of 5.5 months was observed for cabozantinib compared with placebo in patients with metastatic MTC with documented radiographic progression. Among subgroups, the largest OS benefit was observed in RET M918T–positive patients. After extended treatment, the cabozantinib safety profile remained consistent with that reported in the primary analysis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients, their families, the investigators and site staff, and the study teams who participated in this trial. We also thank Mark English, PhD, and Tricia Newell, PhD, of Bellbird Medical Communications and Michael Raffin of Fishawack Communications for providing medical writing and editorial assistance. Medical writing and editorial assistance was supported by Exelixis, Inc.

Funding

Exelixis, Inc (no grant numbers apply).

Disclosure

MS received grant support from Exelixis, Inc., and has also received grant support, personal fees, and non-financial support from AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Genzyme, Bayer, and Eisai. RE consulted for Exelixis, Inc., Bayer, Genzyme, AstraZeneca, Eisai, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Served on speaker bureaus for Exelixis, Inc., Bayer, Genzyme, and AstraZeneca. SM received travel-related financial support from Exelixis, Inc. PS is a lead investigator on Exelixis, Inc., clinical trials, consulted for Exelixis, Inc., and received financial support for advisory functions, educational activities, and related travel. MB received grant support and personal fees from Exelixis, Inc., AstraZeneca, and Genzyme. MS received grant support and personal fees from Exelixis, Inc. LL consulted for Eisai, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Corp., Merck Serono, Boehringer Ingelheim, Debiopharm Group, Sobi, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Roche, and Amgen, received research grant support from Eisai, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Corp., Merck Serono, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, AstraZeneca, and Roche, and has received travel-related financial support from Merck Sorono, Debiopharm Group, Sobi, Bayer, and Amgen. JK is a member of Bayer Health Care Advisory Board, and received honoraria from AstraZeneca, Eisai, Exelixis, Inc., Ipsen, Novartis, Oxigene, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Sobi. MK received non-financial support from Exelixis, Inc., and he has also received personal fees and non-financial support from Sobi, Sanofi, and Eisai. AstraZeneca and Bayer have provided grant support, personal fees, and non-financial support. BN received personal fees from Exelixis, Inc. EC received speaking and consulting fees from Eisai and serves on advisory boards for Pfizer, Merck, AstraZeneca, and Bristol-Myers Squibb. LW received personal fees from Amgen, Blueprint, Eisai, Loxo, and Merck. DC is an employee and stock holder of Exelixis, Inc., and receives shared royalties from UCSF patent. YY and MM are employees and stock holders of Exelixis, Inc. DB received grant support from Exelixis, Inc. SS has received personal fees from Eisai, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Loxo, and Onyx. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Pusztaszeri MP, Bongiovanni M, Faquin WC.. Update on the cytologic and molecular features of medullary thyroid carcinoma. Adv Anat Pathol 2014; 21: 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roman S, Lin R, Sosa JA.. Prognosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma: demographic, clinical, and pathologic predictors of survival in 1252 cases. Cancer 2006; 107: 2134–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Links TP, Verbeek HH, Hofstra RM, Plukker JT.. Endocrine tumours: progressive metastatic medullary thyroid carcinoma: first- and second-line strategies. Eur J Endocrinol 2015; 172: R241–R251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lodish MB, Stratakis CA.. RET oncogene in MEN2, MEN2B, MTC and other forms of thyroid cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 2008; 8: 625–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kouvaraki MA, Shapiro SE, Perrier ND. et al. RET proto-oncogene: a review and update of genotype-phenotype correlations in hereditary medullary thyroid cancer and associated endocrine tumors. Thyroid 2005; 15: 531–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wells SA Jr., Robinson BG, Gagel RF. et al. Vandetanib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic medullary thyroid cancer: a randomized, double-blind phase III trial. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 134–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Moura MM, Cavaco BM, Pinto AE, Leite V.. High prevalence of RAS mutations in RET-negative sporadic medullary thyroid carcinomas. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011; 96: E863–E868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Elisei R, Cosci B, Romei C. et al. Prognostic significance of somatic RET oncogene mutations in sporadic medullary thyroid cancer: a 10-year follow-up study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 682–687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schilling T, Burck J, Sinn HP. et al. Prognostic value of codon 918 (ATG–>ACG) RET proto-oncogene mutations in sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2001; 95: 62–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Agrawal N, Jiao Y, Sausen M. et al. Exomic sequencing of medullary thyroid cancer reveals dominant and mutually exclusive oncogenic mutations in RET and RAS. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98: E364–E369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boichard A, Croux L, Al Ghuzlan A. et al. Somatic RAS mutations occur in a large proportion of sporadic RET-negative medullary thyroid carcinomas and extend to a previously unidentified exon. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97: E2031–E2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Papotti M, Olivero M, Volante M. et al. Expression of Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) and its Receptor (MET) in Medullary Carcinoma of the Thyroid. Endocr Pathol 2000; 11: 19–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Soh EY, Duh QY, Sobhi SA. et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression is higher in differentiated thyroid cancer than in normal or benign thyroid. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997; 82: 3741–3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Elisei R, Schlumberger MJ, Muller SP. et al. Cabozantinib in progressive medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Oncol 2013; 31: 3639–3646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yakes FM, Chen J, Tan J. et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther 2011; 10: 2298–2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sherman SI, Clary D, Elisei R. et al. Correlative analyses of RET and RAS mutations in a phase 3 trial of cabozantinib in patients with progressive, metastatic medullary thyroid cancer. Cancer 2016; 122: 3856–3864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Plaza-Menacho I, Barnouin K, Goodman K. et al. Oncogenic RET kinase domain mutations perturb the autophosphorylation trajectory by enhancing substrate presentation in trans. Mol Cell 2014; 53: 738–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Salvatore D, Melillo RM, Monaco C. et al. Increased in vivo phosphorylation of RET tyrosine 1062 is a potential pathogenetic mechanism of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B. Cancer Res 2001; 61: 1426–1431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Iwashita T, Murakami H, Kurokawa K. et al. A two-hit model for development of multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2B by RET mutations. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2000; 268: 804–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Haber DA, Bell DW, Sordella R. et al. Molecular targeted therapy of lung cancer: EGFR mutations and response to EGFR inhibitors. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 2005; 70: 419–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bentzien F, Zuzow M, Heald N. et al. In vitro and in vivo activity of cabozantinib (XL184), an inhibitor of RET, MET, and VEGFR2, in a model of medullary thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2013; 23: 1569–1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Eng C, Mulligan LM, Healey CS. et al. Heterogeneous mutation of the RET proto-oncogene in subpopulations of medullary thyroid carcinoma. Cancer Res 1996; 56: 2167–2170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.