Abstract

Background

Eribulin is a microtubule dynamics inhibitor with a novel mechanism of action. This phase 3 study aimed to compare overall survival (OS) in patients with heavily pretreated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) receiving eribulin to treatment of physician’s choice (TPC).

Patients and methods

Patients with advanced NSCLC who had received ≥2 prior therapies, including platinum-based doublet and epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor, were randomly assigned to receive eribulin or TPC (gemcitabine, pemetrexed, vinorelbine, docetaxel). The primary endpoint was OS. Secondary endpoints were progression-free survival and objective response rate.

Results

Five hundred and forty patients were randomized to either eribulin (n = 270) or TPC (n = 270). Median OS for eribulin and TPC was the same: 9.5 months [hazard ratio (HR): 1.16; 95% confidence interval: 0.95–1.41; P = 0.13]. Progression-free survival for eribulin and TPC was 3.0 and 2.8 months, respectively (HR: 1.09; 95% confidence interval: 0.90–1.32; P = 0.39). The objective response rate was 12% for eribulin and 15% for TPC. Clinical benefit rate (eribulin, 57%; TPC, 55%) and disease control rate (eribulin, 63%; TPC, 58%) were similar between treatment arms. The most common adverse event was neutropenia, which occurred in 57% of eribulin patients and 49% of TPC patients at all grades. Other non-hematologic side-effects were manageable and similar in both groups except for peripheral sensory neuropathy (all grades; eribulin, 16%; TPC, 9%).

Conclusion

This phase 3 study did not demonstrate superiority of eribulin over TPC with regard to overall survival. However, eribulin does show activity in the third-line setting for NSCLC.

Trial registration ID

Keywords: eribulin, non-small cell lung cancer, phase 3, chemotherapy

Key Message

This phase 3 study evaluated overall survival among patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer who received eribulin or treatment of physician’s choice. Although this study did not demonstrate superiority of eribulin in the primary end point of overall survival, eribulin showed activity in the third-line setting and has a manageable safety profile.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality, accounting for more than 1.8 million new cases and 1.5 million deaths worldwide in 2012 [1]. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is responsible for 80%–85% of all cases of lung cancer [2]. There are three main types of NSCLC: adenocarcinoma, squamous-cell carcinoma, and large-cell carcinoma [2]. More than 50% of patients present with advanced NSCLC, and the 5-year survival rate is <5% [3, 4]. Although improved survival has been shown with first-line platinum-based doublet chemotherapy, the majority of patients have disease progression during or after therapy [5, 6].

The introduction of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs; e.g. erlotinib, gefitinib, afatinib), the anaplastic lymphoma kinase and ROS Oncogene 1 inhibitor (crizotinib), and immuno-oncology agents has led to marked changes in the NSCLC treatment landscape based on tumor histology and molecular biomarkers [3, 7]. However, chemotherapy still plays an important role in patients with advanced NSCLC. Furthermore, despite the availability of second-line therapies, including pemetrexed, erlotinib, and docetaxel, clinical evidence of third-line or later treatment options still remains limited [8, 9].

The non-taxane, microtubule dynamics inhibitor eribulin is a synthetic analog of halichondrin B. Eribulin is approved for the treatment of patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) who have previously received at least two chemotherapeutic regimens (in the USA) or at least one chemotherapeutic regimen (in Europe) for metastatic disease, including an anthracycline and a taxane (in either the adjuvant or metastatic setting) [10, 11]. In study 305/EMBRACE, eribulin significantly improved overall survival (OS) compared with treatment of physician’s choice (TPC) in patients with locally recurrent or MBC after at least two previous regimens for advanced disease [12]. Study 301, which compared eribulin with capecitabine in patients with advanced breast cancer, did not demonstrate significantly improved OS or progression-free survival (PFS) with eribulin treatment [13]. In a phase 3 study comparing eribulin with dacarbazine, eribulin significantly improved OS in patients with advanced liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma [14].

The efficacy of eribulin has been evaluated in several studies for the treatment of advanced NSCLC. A phase 2, single-arm study in patients pretreated with platinum- and taxane-based therapy demonstrated an objective response rate (ORR) of 5% for eribulin, among which 7% of taxane-sensitive patients achieved partial response (PR), but none of the taxane-resistant patients achieved PR [15]. In another phase 2 study of eribulin monotherapy, patients with pretreated, advanced NSCLC had an ORR of 10% [16]. A phase 2 study in patients with pretreated, advanced NSCLC randomized to a 21- or 28-day schedule of eribulin followed by erlotinib demonstrated ORRs of 13% and 17%, respectively [17]. In these studies, ORRs were comparable to or better than those from pivotal randomized trials evaluating other agents as monotherapy in the second- or third-line setting for advanced NSCLC [9, 18]. Based on these data, we compared eribulin with TPC in a phase 3 study of patients with advanced NSCLC.

Methods

Study design

This was a randomized, open-label, multicenter phase 3 study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01454934). TPC (decided by the physician before randomization) was limited to four chemotherapeutic agents commonly used after failure of two previous lines of therapy [3, 19]: vinorelbine, gemcitabine, docetaxel, or pemetrexed (for patients with non-squamous histology only). Following screening and baseline assessments, patients were randomized 1 : 1 to receive eribulin mesylate 1.4 mg/m2 [equivalent to 1.23 mg/m2 eribulin (expressed as free base)] intravenously (i.v.) over 2–5 min on days 1 and 8 of 21-day cycles, or one of the following treatments: vinorelbine 30 mg/m2 i.v. on day 1, every 7 days; gemcitabine 1250 mg/m2 i.v. on days 1 and 8, every 21 days (or 1000 mg/m2 i.v. on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days); docetaxel i.v. 75 mg/m2 on day 1, every 21 days; or pemetrexed 500 mg/m2 i.v. on day 1, every 21 days. Dosage and/or schedule variation for TPC followed regional prescribing information for advanced NSCLC.

Treatment occurred in 21-day cycles until evidence of disease progression, development of unacceptable toxicity, or withdrawal of consent. Survival follow-up was conducted every 12 weeks on all patients while alive or until they withdrew consent. Patients still receiving treatment or in survival follow-up at the end of the randomization phase [occurring when the target number of events (approximately 425 deaths) was observed] entered an extension phase and continued receiving treatment of the same therapy or had follow-up for survival.

Patients

Key inclusion criteria included patients aged ≥18 years with histologically or cytologically confirmed advanced NSCLC that was not amenable to surgery or radiotherapy; ≥2 prior treatment regimens for advanced NSCLC (including platinum-based chemotherapy, and an anti-EGFR TKI in patients with tumors harboring activating EGFR mutations); Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status of 0, 1, or 2; radiographic evidence of disease progression as defined by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST v.1.1) during or after the last treatment regimen and before study entry.

Key exclusion criteria included patients who had not recovered from toxicities as a result of prior anti-cancer therapy to grade <2, except for peripheral neuropathy (grade > 2) and alopecia; had a high probability of long QT syndrome or QTc interval >500 ms; or had brain or subdural metastases (unless asymptomatic not requiring treatment or adequately treated, with confirmed radiographic stability).

Randomization was achieved using an interactive voice and online response system. All patients provided written informed consent. Approval was obtained from independent ethics committees and regulatory authorities in participating countries. The study was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (WMA General Assembly, Tokyo, 2004), guidelines of the International Conference for Harmonization/Good Clinical Practice (CPMP/ICH/135/95), and local ethical and legal requirements.

Study assessments

The primary efficacy endpoint was OS, measured from the date of randomization until date of death from any cause. If confirmation of death was unavailable, patients were censored at the last date known to be alive or study cut-off date, whichever was earlier. Secondary efficacy endpoints were PFS, defined as the time from date of randomization to date of first documentation of disease progression, or death (whichever occurred first), and ORR, defined as the proportion of patients who had best overall response of complete response (CR) or PR per RECIST v1.1.

Exploratory endpoints included clinical benefit rate (CBR), defined as the proportion of patients who had best overall response (CR or PR); durable stable disease (SD), defined as the proportion of patients who had a duration of SD for ≥11 weeks; disease control rate (DCR), defined as the proportion of patients who had best overall response of CR, PR, or SD; and quality of life (QoL) scores as measured using the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ)-C30 and EORTC QLQ-LC13.

Safety and tolerability were assessed via the reporting of adverse events (AEs) and through physical examination and regular monitoring. AEs were graded using Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0 and were classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities. Tumor assessments using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging were carried out during screening, and every 6 weeks during the randomization and extension phases, or sooner, if clinically indicated, until disease progression.

Statistical analysis

OS and PFS were compared using the log-rank test, stratified by histology, TPC option, and geographic region, with a significance level of 0.05 (two-sided). Median OS and median PFS were calculated for each treatment arm with two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CI). Kaplan–Meier survival probabilities for each arm were plotted over time. Treatment effect was estimated using a Cox proportional hazards model, stratified by treatment arm, histology, TPC option, and region, from which hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated and presented with two-sided 95% CI.

All efficacy analyses were carried out on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which comprised all randomized patients. The estimated median OS of the TPC arm was expected to be ∼5.4 months, and an improvement of 2.0 months would be derived from the objective of achieving an HR of 0.73. The overall false-positive rate was set at 0.05 assuming a two-sided test and 90% power. Based on these assumptions, the target number of events was estimated to be 425 events (deaths). To achieve this target, the estimated sample size was 540 patients. The primary OS analysis was carried out when the target number of events had occurred across both treatment arms. The difference between treatment groups for the secondary endpoint of ORR, as well as the exploratory endpoints (CBR, DCR, and durable SD), was evaluated using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel χ2 test, stratified for histology, TPC option, and region, with an α level of 0.05 (two-sided).

The fixed-sequence procedure was used to control the overall type I error rate of analyses for secondary endpoints (α level 0.05; two-sided). Safety data were summarized descriptively using the safety dataset, which comprised all randomized patients who had received at least one dose of study treatment and had at least one post-baseline safety evaluation. Statistical analyses were carried out using SAS software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

This study was conducted at 92 sites in 14 countries from September 2011 to May 2014. Study sites were divided into three geographic regions: USA, Canada, Western Europe, and Australia (Region 1, 259 patients); Eastern Europe and Asia, excluding Japan (Region 2, 161 patients); and Japan (Region 3, 120 patients). A total of 540 patients were included in the study (ITT population; supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). Patients were randomized 1 : 1 to receive eribulin or TPC [vinorelbine, 72 (27%); gemcitabine, 85 (32%); docetaxel, 66 (24%); pemetrexed, 47 (17%)].

Patient characteristics

Baseline patient demographics and disease characteristics were well balanced between treatment arms (Table 1). Prior anti-cancer therapies were similar between arms, and most patients had received ≥3 prior treatment regimens for advanced NSCLC (Table 1). Prior treatment of advanced NSCLC with an EGFR TKI occurred in ∼21% of patients (20% in eribulin arm and 22% in TPC arm, Table 1), while ∼15% of the total patients had an EGFR mutation. For the subgroup of docetaxel as TPC, 23% of patients received a prior taxane-based therapy for advanced NSCLC in both arms.

Table 1.

Baseline and demographic characteristics: intent-to-treat population

| Eribulin (n=270) | TPC (n=270) | |

|---|---|---|

| Median age (range), years | 62.0 (29–84) | 62.0 (32–85) |

| Male, n (%) | 163 (60.4) | 169 (62.6) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 151 (55.9) | 152 (56.3) |

| Asian | 109 (40.4) | 111 (41.1) |

| Othera | 10 (3.7) | 7 (2.6) |

| ECOG-PS status, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 71 (26.3) | 81 (30.0) |

| 1 | 172 (63.7) | 170 (63.0) |

| 2 | 27 (10.0) | 19 (7.0) |

| Smoking history/status, n (%) | ||

| Never smoked | 74 (27.4) | 70 (25.9) |

| Former smoker | 160 (59.3) | 162 (60.0) |

| Current smoker | 36 (13.3) | 38 (14.1) |

| Histology, n (%) | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 54 (20.0) | 59 (21.9) |

| EGFR mutation status, n (%) | ||

| Positive | 44 (16.3) | 39 (14.4) |

| Negative | 167 (61.9) | 172 (63.7) |

| Unknown | 59 (21.9) | 59 (21.9) |

| No. of prior therapies for advanced NSCLC, n (%) | ||

| ≤1 | 8 (3.0) | 10 (3.7) |

| 2 | 117 (43.3) | 108 (40.0) |

| 3 | 74 (27.4) | 87 (32.2) |

| 4 | 53 (19.6) | 42 (15.6) |

| ≥5 | 18 (6.7) | 23 (8.5) |

| Type of previous therapy, n (%) | ||

| Neoadjuvant | 8 (3.0) | 12 (4.4) |

| Adjuvant | 31 (11.5) | 20 (7.4) |

| Maintenance | 17 (6.3) | 17 (6.3) |

| Unknown or missing | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| Prior therapies for advanced NSCLC, n (%) | ||

| Platinum-based therapies | 268 (99.3) | 269 (99.6) |

| EGFR TKI | 55 (20.4) | 58 (21.5) |

| Radiotherapy | 107 (39.6) | 136 (50.4) |

ECOG-PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TPC, treatment of physician’s choice.

Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska native, native Hawaiian or other Pacific islander, or missing.

Efficacy

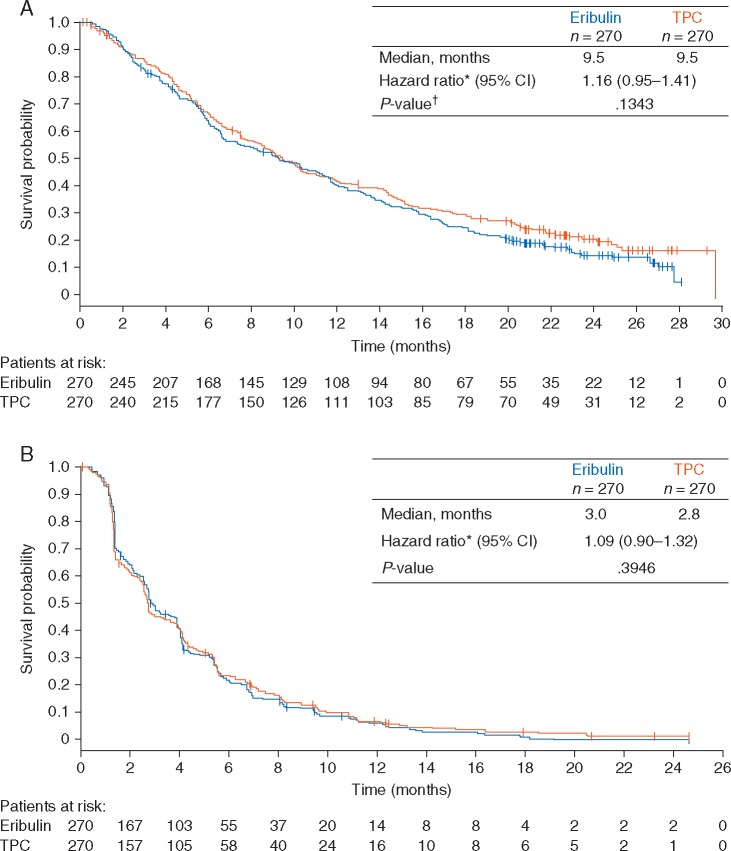

Median OS was 9.5 months for eribulin versus 9.5 months for TPC (HR: 1.16; 95% CI: 0.95–1.41; P = 0.134; Figure 1A). Median PFS was 3.0 months for eribulin versus 2.8 months for TPC (HR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.90–1.32; P = 0.395; Figure 1B). ORRs were 12% and 15% in the eribulin and TPC arms, respectively (Table 2). In the eribulin arm, 51% of patients showed SD compared with 43% of patients in the TPC arm (Table 2). The exploratory endpoints of CBR and DCR were similar between treatment arms (Table 2). QoL assessments using QLQ-C30 showed similar patient responses in both the eribulin and TPC arms. In the Global Health Status category, mean scores ranged between 62.5 and 57.1 (n > 50). Symptom measurements using QLQ-LC13 were also similar between treatment arms.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier graphs of (A) overall survival and (B) progression-free survival of the intent-to-treat population.

Table 2.

Response rates for the intent-to-treat population (investigator assessment)

| Eribulin (n=270) | TPC (n=270) | |

|---|---|---|

| Response rates, n (%) | ||

| Complete response | 2 (0.7) | 0 |

| Partial response | 31 (11.5) | 41 (15.2) |

| Stable disease | 138 (51.1) | 115 (42.6) |

| Progressive disease | 79 (29.3) | 84 (31.1) |

| Not evaluable | 20 (7.4) | 30 (11.1) |

| Objective response rate, % | 12.2 | 15.2 |

| Disease control rate, % | 63.3 | 57.8 |

| Clinical benefit rate, % | 57.4 | 54.8 |

Objective response rate = complete response + partial response; disease control rate = complete response + partial response + stable disease; clinical benefit rate = complete response + partial response + durable stable disease (≥11 weeks).

TPC, treatment of physician’s choice.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses showed that OS was similar between treatment arms for tumor histology, baseline ECOG performance status, EGFR mutation status, and prior anti-cancer therapies for advanced disease (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). In several subgroups, including geographic region and planned TPC, OS differences were observed between treatment arms (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online); however, this study was not powered to draw conclusions from these analyses.

Safety

The median (range) duration of treatment was 12.0 (2.1–109.9) weeks with eribulin and 12.0 (1.0–111.6) weeks with TPC. Median number (range) of cycles was 4.0 (1–36) with eribulin and 4.0 (1–37) with TPC. The relative dose intensity for eribulin was 93%. Serious adverse events (AEs) were reported in 36% of patients receiving eribulin and 32% of patients receiving TPC. The most common AEs, with an incidence of ≥10%, are reported in Table 3. Grade ≥3 asthenia was more frequently observed in the eribulin arm (8.2%) than in the TPC arm (2.6%). In the eribulin arm, there was one treatment-related death (cardiac failure), compared with none in the TPC arm.

Table 3.

Hematologic and nonhematologic adverse events (AEs) with an Incidence of ≥ 10% in either arm: safety population

| Eribulin (n=269) % |

TPC (n=268) % |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade | Grade ≥3 | Any grade | Grade ≥3 | |

| Hematologic AEs: incidence ≥10% | ||||

| Neutropeniaa | 56.9 | 48.7 | 48.9 | 31.7 |

| Leukopeniab | 30.5 | 19.3 | 31.7 | 14.6 |

| Anemia | 21.9 | 2.2 | 27.2 | 7.1 |

| Nonhematologic AEs: incidence ≥10% | ||||

| Decreased appetite | 36.8 | 2.6 | 25.7 | 1.5 |

| Alopecia | 30.1 | 0 | 15.7 | 0 |

| Nausea | 27.1 | 1.1 | 29.1 | 1.5 |

| Fatigue | 24.5 | 4.1 | 23.5 | 3.7 |

| Constipation | 23.4 | 0.7 | 23.9 | 0.7 |

| Dyspnea | 23.4 | 7.8 | 21.6 | 6.3 |

| Asthenia | 22.7 | 8.2 | 21.6 | 2.6 |

| Pyrexia | 18.6 | 0 | 19.4 | 0.4 |

| Cough | 16.0 | 0.4 | 15.7 | 0 |

| Peripheral sensory neuropathy | 16.0 | 3.3 | 9.0 | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 16.0 | 0.4 | 13.1 | 0.7 |

| Diarrhea | 14.9 | 1.1 | 16.8 | 0.7 |

| Edema, peripheral | 14.5 | 0.4 | 11.6 | 0 |

| Headache | 13.0 | 1.5 | 7.5 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 10.8 | 0 | 14.2 | 0.7 |

| Myalgia | 10.4 | 0.7 | 9.7 | 0.7 |

| Malaise | 8.2 | 0.7 | 10.8 | 0.7 |

TPC, treatment of physician’s choice.

Neutropenia included neutrophil count decreased.

Leukopenia included white blood cell count decreased.

Post-treatment anti-cancer therapy

Overall, 54% of patients in the eribulin arm and 57% of patients in the TPC arm received anti-cancer therapy after study completion. Radiotherapy was received by 29% of patients in the eribulin arm and 31% of patients in the TPC arm. In the eribulin arm, 3% of patients underwent surgery after completing the study compared with 5% of patients in the TPC arm. Similar proportions of patients in each arm received EGFR-inhibitor therapy (16% in the eribulin arm, 16% in the TPC arm). The most frequently used anti-cancer drugs after study discontinuation were vinorelbine (17% of eribulin patients and 14% of TPC patients); gemcitabine (15% of eribulin patients and 16% of TPC patients), and docetaxel (16% of eribulin patients and 9% of TPC patients).

Discussion

Eribulin is an active single agent in patients with MBC, advanced soft-tissue sarcoma, and advanced NSCLC [12, 14–16, 20]. In this study, a significant improvement in OS or PFS was not observed with eribulin compared with TPC. Median OS in the eribulin arm was 9.5 months, similar to that in the TPC arm, which comprised four active agents in the setting of NSCLC treatment. Median PFS was slightly longer with eribulin compared with TPC (3.0 versus 2.8 months).

OS in the TPC arm was longer than the presumed OS of 5.4 months. This may be explained, in part, by the large proportion of Asian patients (∼41%) in the study population. Because the activating EGFR mutation rate is known to be elevated in Asian populations relative to Caucasian populations, patients receiving EGFR TKIs following progression may have contributed to improved survival outcomes [21].

Our results are in contrast to those of previous phase 3 trials with eribulin in patients with MBC or advanced liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma, in which a significant improvement in OS with eribulin versus comparator was observed [12, 14]. In our study, eribulin was not superior to TPC with regard to OS or PFS, similar to the findings in the phase 3 trial of eribulin compared with capecitabine in advanced breast cancer [13].

The potential impact of post-progression treatments on OS is important in studies that have several treatment options after failure of first-line therapy, particularly when there is an imbalance in crossover and an observed difference in PFS. In our study, use of any anti-cancer treatments was similar between treatment arms (54% versus 57% in the eribulin and TPC arm, respectively). Additionally, PFS was similar between treatment arms. Although crossover from TPC to eribulin was limited, given that eribulin is not approved for the treatment of NSCLC, no differences in OS were observed.

In a randomized phase 3 trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with NSCLC treated with one prior chemotherapy, median OS was 8.3 versus 7.9 months for pemetrexed and docetaxel, respectively, and median PFS was 2.9 months for each arm [9]. This trend was also observed in the BR.21 trial of erlotinib versus placebo in patients with NSCLC after first- or second-line chemotherapies [8]. Subgroup analysis of patients in the BR.21 trial with wild-type EGFR indicated an OS of 7.9 months with erlotinib, comparable to the OS of effective cytotoxic agents [22].

Although this study was not powered for subgroup analyses, select subgroups were associated with numerically longer survival. Patients receiving docetaxel had longer OS compared with those receiving eribulin. Additionally, patients from North America, Western Europe, and Australia treated with TPC showed longer OS compared with patients treated with eribulin. However, the explanation for these trends is unclear.

Eribulin had a manageable safety profile, consistent with previous studies and similar to the safety profiles of other chemotherapy agents used as part of TPC [12, 13]. The most common grade 3 or 4 AEs were neutropenia and leukopenia; febrile neutropenia leading to death was not observed in either treatment arm. The incidence of other AEs including decreased appetite, nausea, fatigue, and asthenia were similar in both treatment arms. The incidence of peripheral sensory neuropathy at any grade was 16% in the eribulin arm and 9% in the TPC arm, and the incidence of grade ≥3 peripheral sensory neuropathy was 3% in the eribulin arm (and 0% in the TPC arm).

In conclusion, although this study did not demonstrate superiority of eribulin in the primary endpoint of OS, eribulin showed activity in the third-line setting and had a manageable safety profile.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Editorial assistance was provided by Oxford PharmaGenesis Inc., Newtown, PA, USA and was funded by Eisai Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by Eisai Inc., Woodcliff Lake, NJ, USA (no grant numbers apply).

Disclosure

The authors confirm that neither the submitted manuscript nor any similar manuscript, in whole or in part, is under consideration in press, published, or reported elsewhere. NK and NI declare no conflicts of interest. EF has been paid for a consulting or advisory role by Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Roche, Boehringer Ingelheim, and MSD, and has been paid lecture fees to participate in a speakers’ bureau by AstraZeneca, BMS, and Novartis. DRS has received institutional research funding from SCRI. JHK has received institutional research funding from Roche, AstraZeneca, BMS, Lilly, and Boehringer Ingelheim. MO and MG are employees of Eisai Inc. HN has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Taiho Pharmaceutical, AstraZeneca, Ono Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, and Chugai Pharma, and has received institutional research funding from Merck Serono, Pfizer, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Eisai, Chugai Pharma, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo, GlaxoSmithKline, Yakult, Astellas Pharma, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Ono Pharmaceutical. JCHY has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche, Chugai, MSD, AstraZeneca, and Novartis, and has been paid for a consulting or advisory role by Boehringer Ingelheim, Roche/Genetech, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Clovis Oncology, Eli Lilly, MSD Oncology, Merck Serono, Celgene, Astellas Pharma, Bayer, Pfizer, Ono Pharmaceutical, BMS. MS has been paid honoraria by Chugai, Taiho, Eli Lilly Japan, Pfizer Japan, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ono, Novartis, MSD, and Boehringer Ingelheim. FB has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, BMS, Roche, Novartis, Lilly, and Pierre Fabre, and has been paid for a consulting or advisory role by AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Clovis Oncology, Eli Lilly Oncology, F. Hoffman-La Roche Ltd., Novartis, Merck, MSD, Pierre Fabre, and Pfizer.

References

- 1. GLOBOCAN 2012: Estimated Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide in 2012. Liver Cancer. International Agency for Research on Cancer. World Health Organization. http://globocan.iarc.fr/Pages/fact_sheets_cancer.aspx (22 June 2017, date last accessed).

- 2. Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD. et al. Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83: 584–594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines®) Non-small Cell Lung Cancer. Version 4. 2016. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf (22 June 2017, date last accessed). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4. SEER Stat Fact Sheets: Lung and Bronchus Cancer. National Institutes of Health. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html (16 February 2016, date last accessed).

- 5. Azzoli CG, Baker S Jr, Temin S. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline update on chemotherapy for stage IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 6251–6266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NSCLC Meta-Analyses Collaborative Group. Chemotherapy in addition to supportive care improves survival in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patient data from 16 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 4617–4625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Besse B, Adjei A, Baas P. et al. 2nd ESMO Consensus Conference on Lung Cancer: non-small-cell lung cancer first-line/second and further lines of treatment in advanced disease. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 1475–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T. et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2005; 353: 123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV. et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 1589–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eisai Inc. Halaven (eribulin mesylate) Injection [Prescribing Information]. Woodcliff Lake, NJ: Eisai Inc, 2016. http://www.halaven.com/pdfs/HALAVEN-Full-Prescribing-Information.pdf (4 August 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eisai Europe Limited. Halaven 0.44 mg/ml Solution for Injection [Summary of Product Characteristics]. Hertfordshire, UK: Eisai Europe Limited; 2016. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/24382 (4 August 2017, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cortes J, O'Shaughnessy J, Loesch D. et al. Eribulin monotherapy versus treatment of physician's choice in patients with metastatic breast cancer (EMBRACE): a phase 3 open-label randomised study. Lancet 2011; 377: 914–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaufman PA, Awada A, Twelves C. et al. Phase III open-label randomized study of eribulin mesylate versus capecitabine in patients with locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer previously treated with an anthracycline and a taxane. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 594–601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Schöffski P, Chawla S, Maki RG. et al. Eribulin versus dacarbazine in previously treated patients with advanced liposarcoma or leiomyosarcoma: a randomised, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2016; 387: 1629–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gitlitz BJ, Tsao-Wei DD, Groshen S. et al. A phase II study of halichondrin B analog eribulin mesylate (E7389) in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer previously treated with a taxane: a California cancer consortium trial. J Thorac Oncol 2012; 7: 574–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spira AI, Iannotti NO, Savin MA. et al. A phase II study of eribulin mesylate (E7389) in patients with advanced, previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2012; 13: 31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mok TS, Geater SL, Iannotti N. et al. Randomized phase II study of two intercalated combinations of eribulin mesylate and erlotinib in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol 2014; 25: 1578–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R. et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2000; 18: 2095–2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Leighl NB. Treatment paradigms for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: first-, second-, and third-line. Curr Oncol 2012; 19: S52–S58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Waller CF, Vynnychenko I, Bondarenko I. et al. An open-label, multicenter, randomized phase Ib/II study of eribulin mesylate administered in combination with pemetrexed versus pemetrexed alone as second-line therapy in patients with advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 2015; 16: 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhou W, Christiani DC.. East meets West: ethnic differences in epidemiology and clinical behaviors of lung cancer between East Asians and Caucasians. Chin J Cancer 2011; 30: 287–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhu CQ, da Cunha Santos G, Ding K. et al. Role of KRAS and EGFR as biomarkers of response to erlotinib in National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group Study BR.21. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26: 4268–4275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.