Abstract

Background

Most patients with multiple myeloma (MM) are considered to be incurable, and relapse owing to minimal residual disease (MRD) is the main cause of death among these patients. Therefore, new technologies to assess deeper response are required.

Patients and methods

We retrospectively analyzed 125 patients with MM who underwent high-dose melphalan plus autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) to detect MRD in autograft/bone marrow (BM) cells using a next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based method and allele-specific oligonucleotide-polymerase chain reaction (ASO-PCR).

Results

NGS-based method was applicable to 90% and this method had at least one to two logs greater sensitivity compared to ASO-PCR. MRD negative by NGS [MRDNGS(−)] (defined as <10−6) in post-ASCT BM cases (n = 26) showed a significantly better progression-free survival (PFS) (96% at 4 years, P < 0.001) and overall survival (OS) (100% at 4 years, P =0.04) than MRDNGS(+) in post-ASCT BM cases (n = 25). When restricting the analysis to the 39 complete response cases, patients who were MRDNGS(−) (n = 24) showed a significantly better PFS than those that were MRDNGS(+) (n = 15) (P =0.02). Moreover, MRDNGS(−) in post-ASCT BM cases (n = 12) showed significantly a better PFS than MRDNGS(+) cases (n = 7) where MRD was not detected by ASO-PCR (P = 0.001). Patients whose autografts were negative by NGS-based MRD assessment (<10−7) (n = 19) had 92% PFS and 100% OS at 4 years post-ASCT. Conversely, the NGS-based MRD positive patients who received post-ASCT treatment using novel agents (n = 49) had a significantly better PFS (P = 0.001) and tended to have a better OS (P= 0.214) than those that were untreated (n = 33).

Conclusions

Low level MRD detected by NGS-based platform but not ASO-PCR has significant prognostic value when assessing either the autograft product or BM cells post-ASCT.

Keywords: next-generation sequencing, minimal residual disease, myeloma, autologous stem-cell transplantation

Key Message

• Next-generation sequencing-based minimal residual disease (MRD) assessment of autograft samples and bone marrow obtained post-autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) in multiple myeloma patients (MM) has significant prognostic value.

• Post-ASCT treatment improves clinical outcomes in MM patients whose autografts were positive by next-generation sequencing-based MRD assessment.

Introduction

Autologous stem-cell transplantation (ASCT) in conjunction with novel therapeutic drugs can dramatically improve response rates and the prognosis of patients with multiple myeloma (MM). However, most patients with MM are considered to be incurable, and relapse owing to minimal residual disease (MRD) is the main cause of death among these patients. Therefore, new technologies to assess deeper response are required. We utilized a sequencing method, which employs consensus primers and next-generation sequencing (NGS) to amplify and sequence all rearranged immunoglobulin gene segments present in a myeloma clone to assess MRD detection in patients with MM in the ASCT setting.

Patients and methods

One hundred and twenty-five Japanese patients with newly diagnosed MM who received various induction regimens prior to ASCT were retrospectively screened and analyzed. The patients received high-dose melphalan plus ASCT and were followed up between 15 June 2004 and 15 September 2016 in the hospitals of our research group. The median follow-up for survivors was 3.5 years (range 0.5–10.5 years). MM was diagnosed according to the IMWG criteria [1], and the patients’ response to therapy was assessed using the International Uniform Response Criteria [2]. All patients had achieved a partial response (PR) or better after ASCT. One or two BM slides from 94 MM patients and fresh/frozen BM cells from 31 MM patients at diagnosis, as well as autografts/post-ASCT BM cells from each patient, were obtained for DNA extraction [3]. The patients’ characteristics whose MRD were analyzed are shown in supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online. Conventional G-banding for metaphase spreads of BM cells in 125 patients and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of t(4;14), t(14;16), and del(17p) for BM-derived interphase cells in 81 patients were performed. The samples for MRD analysis were obtained from autograft and BM cells after post-ASCT day 24 to 2808 (median day 372) when the best response [at least very good partial response (VGPR)] was achieved. All patients were treated on institutional review board-approved protocols or standard treatment protocols and gave consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Kanazawa University Graduate School of Medical Science.

MRD detection by NGS

We performed NGS to detect MRD in autograft and BM cells as previously described (Adaptive Biotechnologies Corp, Seattle, WA) [4]. Because the sensitivity level is limited by DNA input [4] and more DNA could be extracted from the autograft than BM, the thresholds of MRD in autograft and BM were 1 × 10−7 and 1 × 10−6, respectively. DNA of median 103 μg (range 59-288 μg) of autograft and that of median 19 μg (range 6-36 μg) of BM were used and the average number of reads per input template DNA of 49 in autograft and that of 16 in BM were analyzed by NGS to reach the 10−7 and 10−6 threshold, respectively. We used ∼2 ml-BM sample and 2-6 ml combined aliquot sample of autografts that were used for ASCT. In cases in which two or more tumor clones existed, the clone with the highest MRD value was reported.

MRD detection by ASO-PCR

We also performed MRD detection in autograft and BM cells using IGH-based ASO-PCR using TaqMan technology as described previously [5]. We used 0.6 μg DNA for all analyzed samples and the sensitivity was 10−4–10−5.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test. The concordance was analyzed in log space using the Pearson coefficient test. Progression-free survival (PFS) was defined as survival from ASCT until disease progression [2] or death from any cause. The PFS and overall survival (OS) were calculated from the time of ASCT until the date of death, by any cause, or the date of last contact. Because the sampling time of BM was based on the best response (at least VGPR), we also analyzed PFS and OS from the MRD assessment timepoint. Survival curves were plotted according to the Kaplan–Meier method, and the log-rank test was used for comparisons among the groups. A multivariate analysis was conducted by Cox proportional hazard with Firth’s penalized (partial) likelihood and was used to calculate the hazard ratios (HR) for each variable along with the 95% confidence interval (CI) [6]. All statistical analyses were performed using the EZR software package (Saitama Medical Center/Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan) [7]. P values of <0.05 were considered significant in all analyses.

Results

Clonality assessment of B-cell receptor rearrangements in diagnostic BM samples (see also supplementary results, available at Annals of Oncology online)

We first assessed diagnostic samples from 125 patients with MM for clonal sequences at the IgH-VDJ, IgH-DJ, and IgK loci using the NGS-based assay. The specific samples that were assessed for high-frequency MM clonal sequences included 31 fresh/frozen BM cells, 84 BM aspirate smear slide samples, 8 BM non-decalcified clot samples, and 2 decalcified BM biopsy samples. Of the 94 BM clot/smear slide/biopsy samples, 4 samples did not contain sufficient DNA (<15 ng). At least one clonal sequence was detected in 31/31 (100%) fresh/frozen BM samples and 82/90 (91%) BM clot/smear slide/biopsy samples resulting in an overall clone identification rate of 113/125 (90%). To assess MRD, autografts for ASCT were available in 101/113 (89%) patients and BM cells post-ASCT were available in 51/113 (45%) patients. We also assessed IgH clonality for ASO-PCR in a subset of patients. Clonotype-specific IgH PCR primers were prepared in 53/82 (65%) and 22/31 (71%) cases using BM smear/decalcified BM biopsy slides and fresh/frozen BM cells respectively resulting in 75/113 (66%) due to the low success rate of patient specific primer design for ASO-PCR (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

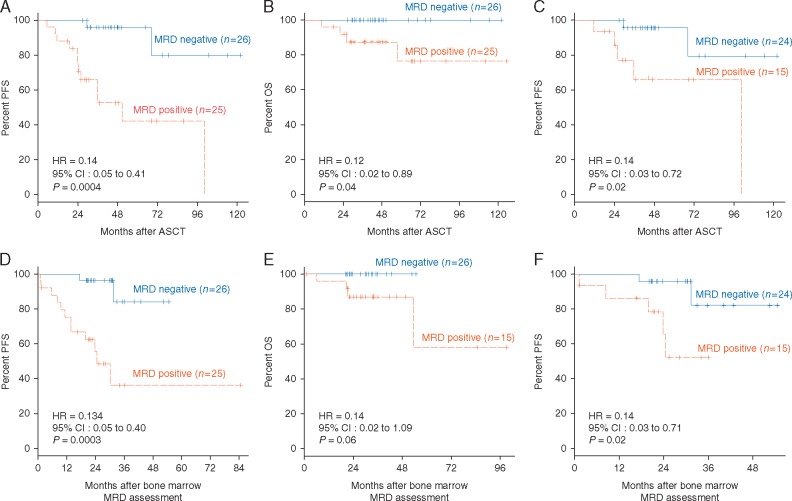

Prognostic value of MRD in post-ASCT BM samples

We assessed post-ASCT BM cells in 51 patients using NGS-based MRD assessment. MRDNGS(−) (MRD negative by NGS) (defined as <10−6) in post-ASCT BM cases (n = 26) showed a significantly better PFS (P =0.0004) and OS (P = 0.04) than MRDNGS(+) post-ASCT BM cases (n = 25) (Figure 1A and B). Three MRDNGS(−) cases who received VAD (vincristine, doxorubicin, and dexamethasone) induction regimen also showed 100% PFS at median follow-up of 114 months (range 103-122). When restricting the analysis to the 39 CR cases, patients who were MRDNGS(−) (n = 24) showed a significantly better PFS than those that were MRDNGS(+) (n = 15) (P = 0.02, Figure 1C). However, only 1 death occurred in the 39 CR cases, and therefore no significant OS difference was observed. Because the samples for MRD analysis were obtained from BM cells post-ASCT when the best response was achieved (at least VGPR), we also analyzed PFS and OS from the MRD assessment timepoint. The results showed a similar pattern (Figure 1D–F).

Figure 1.

Prognostic value of MRD in post-ASCT BM samples for patients with multiple myeloma according to MRD level as determined by deep sequencing (threshold: 10−6). (A) PFS for all patients, (B) OS for all patients, and (C) PFS for patients achieving conventional CR from ASCT. (D) PFS for all patients, (E) OS for all patients, and (F) PFS for patients achieving conventional CR from BM MRD assessment.

Correlation between MRD levels in BM and autograft samples

A subset of patients undergoing ASCT (n = 39) had both BM cells and autograft samples available for MRD assessment. Using the NGS-based technique, we studied whether the quantitative MRD levels in the autograft sample correlates with MRD levels in the BM post-ASCT sample from the same patient. We found a correlation (r = 0.50, P = 0.022) between the two levels with most discrepancies being positive in the autograft and negative in the BM sample (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online) suggesting that the post-ASCT therapy induced MRD negativity in the BM even after the MRD positive autograft was transplanted and another possibilities are the higher sensitivity of MRD evaluation in autograft when compared with that obtained in BM and the non-uniform nature of disease within the BM.

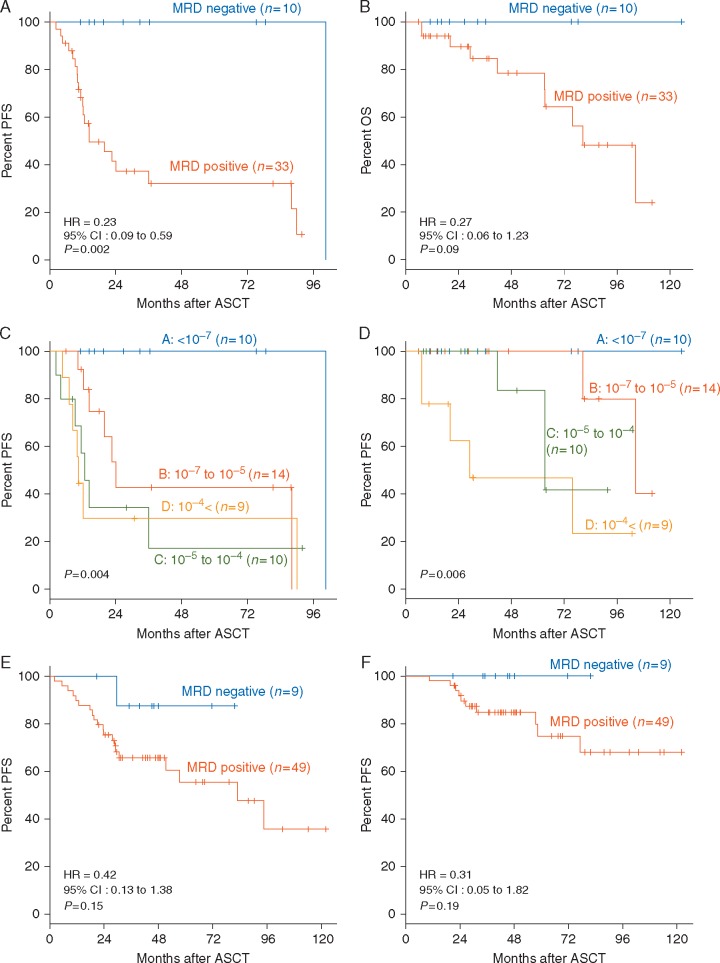

Prognostic value of MRD in autograft samples

We then evaluated the association of clinical outcome with autograft MRD assessment using the NGS-based platform. Among the 43 patients who did not receive post-ASCT treatment, patients with NGS-based MRD negativity [MRDNGS(−)] (defined as <10−7) in the autograft (n = 10) had a significantly better PFS (P = 0.002, Figure 2A) and tended to be better OS (P = 0.09, Figure 2B) than those who were MRD positive (n = 33), with prognosis clearly stratified by the quantitative level of MRD (Figure 2C and D). MRD assessment from the 58 patients who did receive post ASCT treatment using novel agents tended to show a similar pattern (Figure 2E and F). The pre-ASCT responses of 19 patients with MRDNGS(−) in the autograft were 3 CR (16%), 10 VGPR (53%) and 6 PR (32%), whereas the 79 patients with MRDNGS(+) in the autograft were 6 CR (8%), 27 VGPR (34%), 35 PR (44%), 1 SD (1%), and 10 NA (not assessed) (13%). In the autograft, there was no significant difference in the CR rate between MRDNGS(−) and MRDNGS(+) patients.

Figure 2.

Correlation between NGS-based MRD assessment in autografts and clinical outcome. (A) PFS and (B) OS of the 43 patients who did not receive post-ASCT treatment, according to MRD negativity in the autograft as determined by deep sequencing (threshold: 10−7). (C) PFS of series stratified according to different MRD levels <10−7 versus 10−7 to 10−5 versus 10−5 to 10−4 versus 10−4<. (D) OS of series stratified according to different MRD levels <10−7 versus 10−7 to 10−5 versus 10−5 to 10−4 versus 10−4<. (E) PFS and (F) OS among the 58 patients who did receive post-ASCT treatment, according to MRD negativity in the autograft as determined by deep sequencing (threshold: 10−7).

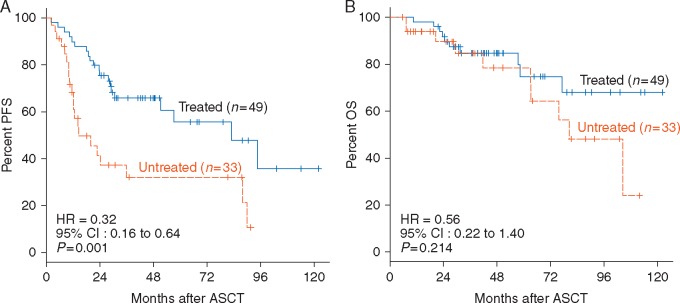

Clinical outcomes associated with MRD-directed post-ASCT treatment

We then studied whether there is evidence that post-ASCT treatment alters clinical outcomes in patients whose autografts were MRD positive by NGS. There were no significant differences between the treated and untreated populations in terms of age, gender, ISS, pre-ASCT response, high-risk chromosomal abnormalities (HRCA), and MRD level (median, range) (data not shown). The NGS-based MRD positive patients who received post-ASCT treatment (n = 49) had a significantly better PFS (P= 0.001, Figure 3A) and tended to have a better OS (P= 0.214, Figure 3B) than those that were untreated (n = 33).

Figure 3.

Clinical outcomes associated with MRD-directed post-ASCT treatment. (A) PFS and (B) OS of the patients whose autografts were MRD positive by NGS according to post-ASCT treatment.

Prognostic significance of low level MRD detected by NGS and undetectable by ASO-PCR

We next compared MRD results in 68 autografts and 25 BM samples assessed by the two MRD assessment methodologies: NGS and ASO-PCR. Thirty-five samples were positive by NGS and negative by ASO-PCR, which is consistent with the higher sensitivity afforded by the NGS platform (10−6 or better) compared with ASO-PCR (10−4–10−5). We observed a high correlation between NGS and PCR MRD results at MRD levels of 10−5 or higher (r = 0.618, P = 0.005) (supplementary Figure S3A, available at Annals of Oncology online).

We then investigated whether patients whose autografts are MRDNGS(+) and MRDASO(−) (MRD negative by ASO-PCR) have different prognosis from those whose autografts were MRDNGS(−). We compared PFS in 7 MRDNGS(−) autograft cases (group 1) with the 11 MRDNGS(+) autograft cases where MRD was not detected by ASO-PCR (group 2). The patients in both groups did not receive any post-ASCT therapy. Group 1 showed significantly a better PFS than group 2 (P= 0.018, supplementary Figure S3B, available at Annals of Oncology online), but there was no difference in OS between the two groups (both 100%).

We compared PFS in 12 MRDNGS(−) in BM post-ASCT (group 3) with the 7 MRDNGS(+) in BM post-ASCT where MRD was not detected by ASO-PCR [MRDASO(−)] (group 4). Group 3 showed significantly a better PFS than group 4 (supplementary Figure S3C and D, available at Annals of Oncology online), but no difference in OS (both 100%).

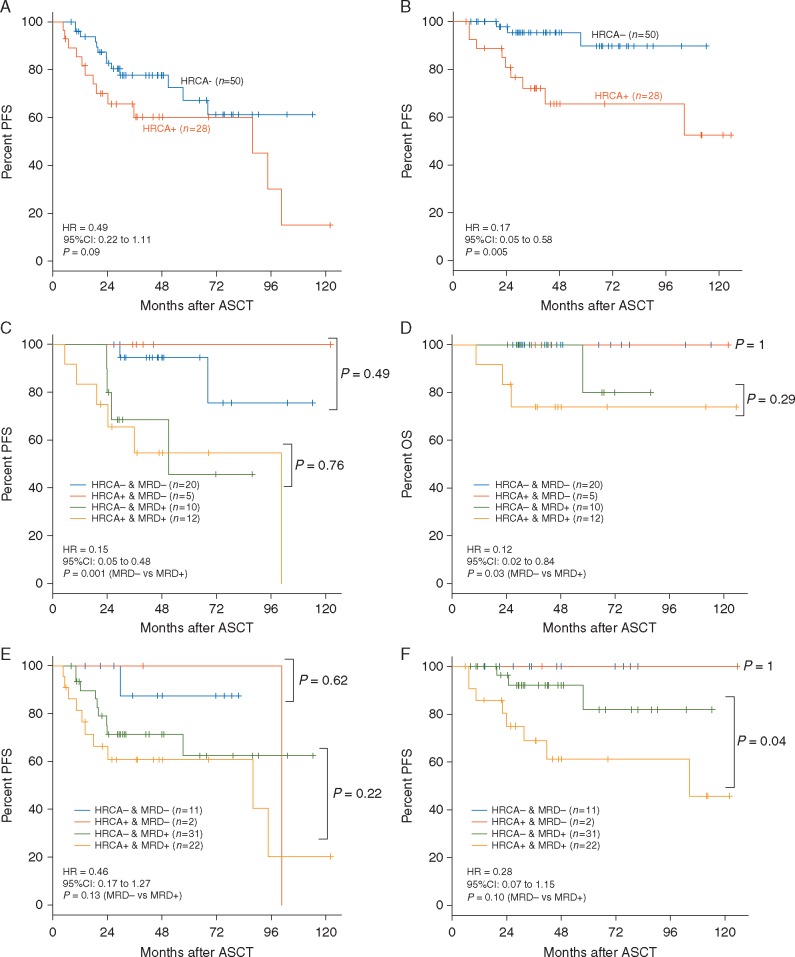

Influence of HRCA on prognosis of MM

Presence of HRCA was assessed in 78 cases, and 28 of 78 (36%) showed HRCA. Specifically, we observed t(4;14) in 17, t(14;16) in 3, del17p in 9 by FISH, t(4;14) and del17p in 1. The cases with HRCA tended to show shorter PFS (P= 0.09, Figure 4A) and significantly shorter OS (P= 0.005, Figure 4B) compared with those without HRCA. HRCA cases achieved MRD negativity in BM post-ASCT in 5 of 17 (30%) and 2 of 24 (8%) in autografts by NGS. One of three del17p cases achieved MRD negativity in BM post-ASCT by NGS, and no del17p cases (n = 6) among HRCA cases achieved MRD negativity in autograft by NGS. On the other hand, non-HRCA cases achieved MRD negativity in BM post-ASCT in 20 of 30 (67%) and 11 of 42 (26%) in autograft. The MRD negativity rate in post-ASCT BM of the non-HRCA cases was significantly higher than that of the HRCA cases (P = 0.02). When we analyzed PFS and OS according to HRCA and the negativity of post-ASCT BM/autograft MRD, MRD negative cases showed better PFS and OS than MRD positive cases (P = 0.001, Figure 4C; P = 0.03, Figure 4D; P = 0.13, Figure 4E; P = 0.10, Figure 4F). HRCA cases attaining MRD negativity showed similar PFS and OS to MRD-negative non-HRCA cases (Figure 4C–F).

Figure 4.

Influence of high-risk chromosomal abnormalities (HRCA) and MRD levels by NGS on prognosis of multiple myeloma. (A) PFS and (B) OS according to HRCA. (C) PFS and (D) OS of series stratified according to HRCA and MRD negativity in BM by NGS and (E) PFS and (F) OS of series stratified according to HRCA and MRD negativity in autograft by NGS.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors

Multivariate analysis was performed using established prognostic factors in addition to MRD negativity in autografts by NGS [data available in 101/113 (89%)]. In a multivariate analysis, the factors that were independently associated with superior PFS were post-ASCT therapy using novel agents (HR = 0.32, P = 0.002) and MRD negativity in autografts by NGS (HR = 0.17, P= 0.002; supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Additionally, MRD negativity in autografts by NGS tended to show a better OS (HR = 0.14, P = 0.074; supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Discussion

In this study, we investigated the prognostic value of MRD assessment in autograft and post-ASCT BM in MM patients using an NGS-based method. Previous studies in different lymphoid neoplasms have reported a sensitivity difference between the various techniques, with NGS-based methods demonstrating 1–2 logs greater sensitivity compared to flow cytometry and ASO-PCR, respectively [4, 8–12]. Our results support and further expand on these previous findings. In this study, we noted that the subset of post-ASCT BM samples that were negative by NGS-based method had significantly better PFS compared with the low level MRD positive group, which had undetectable MRD by ASO-PCR (P= 0.001). These results underscore the prognostic relevance of MRD assessment using the higher sensitivity NGS-based approach. Although MFC has advantages such as a fast (within a few hours) MRD result acquisition and relatively low cost [11, 13, 14], the main drawbacks are the need for expertise to perform MFC, and standardization of the MFC method [15], which is currently being developed by the EuroFlow Consortium [13].

When combining analysis of MRD in BM samples post-ASCT with HRCA, we noted that HRCA cases had lower MRD negativity than non-HRCA cases. However, the HRCA MRD negative cases had the same good prognosis as their MRD negative non-HRCA counterparts cases (Figure 4C–F). This result is consistent with the recent report in which MFC was used for MRD analysis [14]. These results reflect that better therapies can bring more patients into MRD negativity and the impact of myeloma biology may be less important than MRD status.

The association between MRD status and clinical outcome presented here may reflect that the presence of MRD positivity means there are contaminating myeloma cells in the product that will be infused back into the patient. Alternatively, the presence of MRD in the autograft can simply indicate that a substantial number of myeloma cells remain in the patient’s body and the homogenous nature of the mobilized autograft relative to the focal nature of myeloma in BM might provide a better sample to assess MRD. The contamination hypothesis may be in contradiction with previous results [16]. Stewart et al. conducted a phase III randomized trial to study whether enrichment of CD34+ autograft cells and purging of malignant plasma cells would affect PFS and OS in a cohort of MM patients receiving autografts. Despite the significant reduction of myeloma cell contamination in the autograft (median 3.1 logs), no improvement was observed in either PFS or OS. However, the utilization of much more effective treatments in this study compared to the previous report precludes definitive conclusion as to the cause of the association between the autograft MRD positivity and clinical outcome.

We investigated whether there was evidence that post-ASCT treatment alters clinical outcomes in patients whose autografts were MRD positive by NGS. NGS-based MRD positive patients who received post-ASCT treatment had a significantly better PFS (P = 0.001) than those that were untreated. Conversely, patients whose autografts were MRD negative by NGS had 92% PFS and 100% OS at 4 years post-ASCT. According to our data, it might be appropriate for the patients who achieve MRD 10−6 negative status to be under careful observation and for the patients who do not achieve MRD 10−6 negativity to receive immediate high-dose melphalan-ASCT followed by maintenance or modern combination therapy such as carfilzomib, lenalidomide and dexamethasone until the achievement of MRD 10−6. MRD-directed treatment strategies will define the depth of response required for sustained benefit and avoid overtreatment of those who have achieved maximal benefit [17].

The major limitations of this study are relatively small sample size and retrospective nature with lack of uniform therapy. As most studies that have evaluated the prognostic value of MRD in patients with MM were small and varied in terms of patient population, treatment, and MRD assessment, two meta-analyses were recently completed [18, 19]. Both analyses showed that MRD negativity was associated with better PFS and OS despite of the difference of the patient population and treatment suggesting that MRD negativity is a strong predictor of clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, low level MRD detected by NGS-based platform, but not ASO-PCR, has significant prognostic value when assessing either the autograft product or BM cells post-ASCT. The findings in this article, particularly regarding the significance of MRD negativity in autograft, should be confirmed in prospective studies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr Yoshiyasu Ogawa and Dr Noriko Kobayashi of LSI Medience Corporation and Ms Rie Oumi and Ms Tomoko Tanaka of Kanazawa University for their technical assistance.

Funding

This research project was supported by the following grants: a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (15K08644), Research Award from the Mitsui Life Social Welfare Foundation, Research Award from the International Myeloma Foundation Japan, and Research Award from the Hokkoku Foundation for Cancer Research (HT). This study was supported in part by research funding from Adaptive Biotechnologies (JZ, MM, VEHC, KAK, MF).

Disclosure

HT received research funding from Takeda and Fujimoto, and honoraria from Celgene and Janssen. SI received research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and honoraria from Celgene. KY received research funding from Takeda and honoraria from Celgene. JZ, MM, VEHC, KAK and MF are employees of Adaptive Biotechnologies. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. International Myeloma Working Group Criteria for the classification of monoclonal gammopathies, multiple myeloma and related disorders: a report of the International Myeloma Working Group. Br J Haematol 2003; 121: 749–757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Durie BG, Harousseau JL, Miguel JS. et al. International uniform response criteria for multiple myeloma. Leukemia 2006; 20: 1467–1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takamatsu H, Ogawa Y, Kobayashi N. et al. Detection of minimal residual disease in patients with multiple myeloma using clonotype-specific PCR primers designed from DNA extracted from archival bone marrow slides. Exp Hematol 2013; 41: 894–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Faham M, Zheng J, Moorhead M. et al. Deep-sequencing approach for minimal residual disease detection in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 2012; 120: 5173–5180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van der Velden VH, van Dongen JJ.. MRD detection in acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients using Ig/TCR gene rearrangements as targets for real-time quantitative PCR. Methods Mol Biol 2009; 538: 115–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Heinze G, Schemper M.. A solution to the problem of monotone likelihood in Cox regression. Biometrics 2001; 57: 114–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kanda Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013; 48: 452–458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Martinez-Lopez J, Lahuerta JJ, Pepin F. et al. Prognostic value of deep sequencing method for minimal residual disease detection in multiple myeloma. Blood 2014; 123: 3073–3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Korde N, Roschewski M, Zingone A. et al. Treatment with carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone with lenalidomide extension in patients with smoldering or newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. JAMA Oncol 2015; 1: 746–754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ladetto M, Bruggemann M, Monitillo L. et al. Next-generation sequencing and real-time quantitative PCR for minimal residual disease detection in B-cell disorders. Leukemia 2014; 28: 1299–1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rawstron AC, Gregory WM, de Tute RM. et al. Minimal residual disease in myeloma by flow cytometry: independent prediction of survival benefit per log reduction. Blood 2015; 125: 1932–1935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ferrero S, Ladetto M, Drandi D. et al. Long-term results of the GIMEMA VEL-03-096 trial in MM patients receiving VTD consolidation after ASCT: MRD kinetics’ impact on survival. Leukemia 2015; 29: 689–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paiva B, van Dongen JJ, Orfao A.. New criteria for response assessment: role of minimal residual disease in multiple myeloma. Blood 2015; 125: 3059–3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Paiva B, Cedena MT, Puig N. et al. Minimal residual disease monitoring and immune profiling in multiple myeloma in elderly patients. Blood 2016; 127: 3165–3174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Flanders A, Stetler-Stevenson M, Landgren O.. Minimal residual disease testing in multiple myeloma by flow cytometry: major heterogeneity. Blood 2013; 122: 1088–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Stewart AK, Vescio R, Schiller G. et al. Purging of autologous peripheral-blood stem cells using CD34 selection does not improve overall or progression-free survival after high-dose chemotherapy for multiple myeloma: results of a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2001; 19: 3771–3779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Landgren O, Giralt S.. MRD-driven treatment paradigm for newly diagnosed transplant eligible multiple myeloma patients. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51: 913–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Landgren O, Devlin S, Boulad M, Mailankody S.. Role of MRD status in relation to clinical outcomes in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients: a meta-analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant 2016; 51: 1565–1568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Munshi NC, Avet-Loiseau H, Rawstron AC. et al. Association of minimal residual disease with superior survival outcomes in patients with multiple myeloma: a meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3: 28–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.