Abstract

Background

Cancer anorexia–cachexia is a debilitating condition frequently observed in NSCLC patients, characterized by decreased body weight, reduced food intake, and impaired quality of life. Anamorelin, a novel selective ghrelin receptor agonist, has anabolic and appetite-enhancing activities.

Patients and methods

ROMANA 3 was a safety extension study of two phase 3, double-blind studies that assessed safety and efficacy of anamorelin in advanced NSCLC patients with cachexia. Patients with preserved Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group ≤2 after completing 12 weeks (w) on the ROMANA 1 or ROMANA 2 trials (0–12 weeks) could enroll in ROMANA 3 and continue to receive anamorelin 100 mg or placebo once daily for an additional 12w (12–24 weeks). The primary endpoint of ROMANA 3 was anamorelin safety/tolerability (12–24 weeks). Secondary endpoints included changes in body weight, handgrip strength (HGS), and symptom burden (0–24 weeks).

Results

Of the 703 patients who completed ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2, 513 patients entered ROMANA 3 (anamorelin, N = 345, mean age 62.0 years; placebo, N = 168; mean age 62.2 years). During ROMANA 3, anamorelin and placebo groups had similar incidences of treatment–emergent adverse events (TEAEs; 52.2% versus 55.7%), grade ≥3 TEAEs (22.4% versus 21.6%), and serious TEAEs (12.8% versus 12.6%). There were 36 (10.5%) and 23 (13.8%) deaths in the anamorelin and placebo groups, respectively; none were drug-related. Improvements in body weight and anorexia–cachexia symptoms observed in the original trials were consistently maintained over 12–24 weeks. Anamorelin, versus placebo, significantly increased body weight from baseline of original trials at all time points (P < 0.0001) and improved anorexia–cachexia symptoms at weeks 3, 6, 9, 12, and 16 (P < 0.05). No significant improvement in HGS was seen in either group.

Conclusion

During the 12–24 weeks ROMANA 3 trial, anamorelin continued to be well tolerated. Over the entire 0–24w treatment period, body weight and symptom burden were improved with anamorelin.

Clinical trial registration numbers

ROMANA 1 (NCT01387269), ROMANA 2 (NCT01387282), and ROMANA 3 (NCT01395914).

Keywords: ROMANA 3, anamorelin, non-small-cell lung cancer, body weight, anorexia–cachexia symptoms, ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2

Introduction

Cancer anorexia–cachexia syndrome is a multifactorial, debilitating condition frequently observed in patients with advanced cancer [1], with a prevalence of 50%–80% [2]. It is characterized by reduced food intake, negative metabolic changes [1], and decreased body weight, primarily due to lean body mass (LBM) loss [3]. Cancer cachexia negatively impacts patients’ quality of life (QOL), leads to decreased survival, and may reduce tolerance of, or responsiveness to, therapy [4]. It frequently occurs in patients with NSCLC [5], where the symptom burden includes substantial appetite and weight loss, as well as fatigue [6, 7].

Ghrelin, the endogenous ligand of the ghrelin receptor, stimulates multiple pathways that regulate body weight, LBM, appetite, and metabolism [8, 9]. In patients with advanced cancer, intravenous administration of ghrelin resulted in substantial caloric intake and appetite increases, with no reports of drug-related adverse events (AEs) [10, 11]. However, ghrelin’s clinical utility is limited by its parenteral administration, combined with its short half-life (<30 minutes).

Anamorelin is a novel, orally active, highly selective ghrelin receptor agonist that activates multiple pathways involved in regulating body weight, LBM, appetite, and metabolism [12]. Several randomized pilot or phase 2 trials have demonstrated anamorelin’s safety and efficacy in increasing LBM, body weight, and appetite in patients with various types of cancer [13–15]. Two international, double-blind phase 3 trials (ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2) assessed the efficacy and safety of anamorelin in patients with advanced NSCLC and cachexia [16]. Anamorelin treatment for 12 weeks was well tolerated and significantly improved lean and fat mass, body weight, and anorexia–cachexia symptoms; no effect was observed on handgrip strength (HGS) [16]. Patients who completed ROMANA 1 or ROMANA 2 could enroll in the ROMANA 3 extension study. This assessed the safety of anamorelin, compared with placebo, for an additional 12 weeks (treatment period 12–24w), and efficacy across the entire 24-week period, encompassing the ROMANA 1, ROMANA 2, and ROMANA 3 study periods.

Materials and methods

Study design

ROMANA 3 (NCT01395914) was a double-blind, safety extension study of the international phase 3 ROMANA 1 (NCT01387269) and ROMANA 2 (NCT01387282) trials. Patients enrolled in ROMANA 1 or ROMANA 2 were randomized (2 : 1) to 12 weeks of daily oral anamorelin 100 mg or placebo. Patients with a preserved Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status ≤2 who completed dosing in either trial could enroll in ROMANA 3. The trial was conducted at 70 hospital and community sites in 18 countries (supplementary Table S1, available at Annals of Oncology online). The protocol was approved by the institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each participating center and complied with the Declaration of Helsinki, the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects, and Good Clinical Practice Guidelines.

Patients

Patients who had completed week 12 in the original trials and whom the investigator considered suitable to receive an additional 12 weeks of study treatment could enroll in ROMANA 3. Eligibility criteria for all patients in the three trials were: ≥18 years of age; histologically confirmed unresectable stage III/IV NSCLC and cachexia (involuntary weight loss of ≥5% within the prior 6 months, or body mass index [BMI] <20 kg/m2); ECOG performance status ≤2; and life expectancy of ≥4 months at screening. Patients could receive concomitant chemotherapy. Those receiving only parenteral nutrition, a concurrent investigational agent other than the study drug, or prescription medications for increasing appetite or treating weight loss (including corticosteroids) were excluded. A summary of glucocorticoid-based concomitant medication administered as antiemetics to patients participating in the ROMANA 3 trial is presented per treatment group in supplementary Table S2, available at Annals of Oncology online. All patients provided written informed consent.

Procedures

Patients enrolled in ROMANA 3 continued to receive anamorelin 100 mg or placebo once daily for an additional 12 weeks (treatment period 12–24 weeks); safety, body weight, and symptom burden were assessed every 4 weeks (16 weeks, 20 weeks, and 24 weeks). All treatment–emergent AEs (TEAEs), study drug related or not, were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0. Body weight was assessed using a specific calibrated scale. HGS (determined at 8 weeks and 12 weeks of ROMANA 3 [20 weeks and 24 weeks of the 0–24 weeks treatment period]) was measured using hand-held dynamometers (Tracker Freedom® Wireless Grip Strength Testing System; JTECH Medical, Midvale, UT, USA). Symptom burden was measured using the 12-item Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale (supplementary Table S3, available at Annals of Oncology online) of the Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Treatment (FAACT) tool [17].

Objectives

The primary objective was to evaluate safety/tolerability of anamorelin over the ROMANA 3 exposure period. Secondary objectives included evaluating effects of anamorelin on body weight, HGS, and symptom burden over the 0–24 weeks treatment period comprising the ROMANA 1, ROMANA 2, and ROMANA 3 trials.

Statistical analyses

No formal sample size calculation was performed for this extension study. Demographics and baseline characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics by treatment group and overall for the intent-to-treat (ITT) population. Baseline (0w) of the original trials was defined as the last measurement obtained before first administration of study drug. Safety was assessed in all patients receiving either extension trial study drug.

Prespecified analyses included mean changes from baseline of original trials in body weight and symptom burden at each visit of ROMANA 3 using a mixed-effects model for repeated measures. Treatment, ECOG status (0–1 versus 2), BMI (>18.5 kg/m2 versus ≤18.5 kg/m2), age (>65 years versus ≤65 years), gender, geographic region, chemotherapy/radiotherapy status, weight loss over prior 6 months, and treatment by time point interaction were considered fixed effects, and baseline a covariate. The restricted maximum likelihood method was used. Changes in HGS from baseline were analyzed using the same model. Post-hoc analysis evaluated treatment differences for body weight and symptom burden at each time point of the 0–24w treatment period of the ROMANA 1, ROMANA 2, and ROMANA 3 trials using the mixed-effects model for repeated measures. Least-squares means, corresponding standard errors, and two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived for between-group comparisons. All efficacy analyses were performed on the ITT population. All statistical tests were two-sided; P values of ≤0.05 were deemed statistically significant. SAS (v9.2 or above) was used for data analysis.

Results

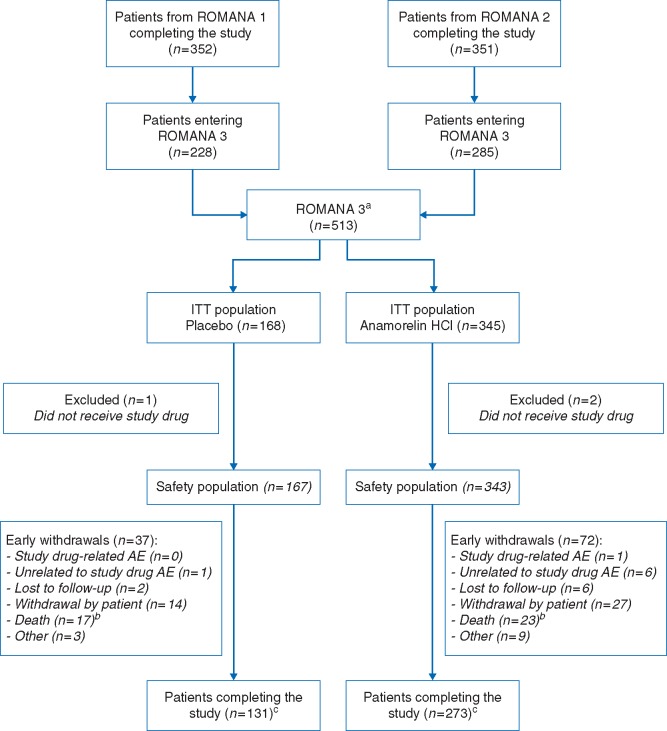

In total, 513 patients (anamorelin, N = 345; placebo, N = 168) were enrolled in ROMANA 3; this comprised 228/352 patients (65%) who completed ROMANA 1, and 285/351 (81%) who completed ROMANA 2 (Figure 1). In total, 99.4% received study drug; the median number of days on treatment during ROMANA 3 was 84.0 days for both treatment groups. Over the entire 0–24w period, 221 patients had received anamorelin (100 mg) for 24 weeks; the mean number of days on anamorelin during this period was 161.1 days (85 + 76.1). Table 1 summarizes demographic and baseline characteristics. There were no major between-group differences, although the anamorelin group included fewer patients with squamous cell carcinoma and more with large cell histology than the placebo group (49.9% versus 53.6%, and 5.2% versus 2.4%, respectively). During the 12–24w safety extension trial, the majority of patients received chemotherapy (supplementary Table S4, available at Annals of Oncology online) or radiotherapy, with similar proportions between treatment arms.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of ROMANA 3. aPatients enrolled in ROMANA 3 stayed on their initial treatment arm (from ROMANA 1 or ROMANA 2). bNo deaths were drug related. cIncluding the patients who did not receive study drug. Patients completing the study are defined as patients finalizing the week 12/day 85 visit. AE, adverse event; ITT, intent-to-treat.

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| ROMANA 3 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Anamorelin 100 mg | Placebo | |

| (n=345) | (n=168) | |

| Mean age, years (SD) | 62.0 (8.5) | 62.2 (8.4) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 262 (75.9) | 125 (74.4) |

| Female | 83 (24.1) | 43 (25.6) |

| Geographic region, n (%) | ||

| North America | 19 (5.5) | 5 (3.0) |

| Western Europe | 135 (39.1) | 72 (42.9) |

| Eastern Europe and Russia | 184 (53.3) | 88 (52.4) |

| Australia | 7 (2.0) | 3 (1.8) |

| ECOG PS of original trial, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 43 (12.5) | 15 (8.9) |

| 1 | 240 (69.5) | 129 (76.8) |

| 2 | 62 (18.0) | 24 (14.3) |

| ECOG PS of extension trial, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 31 (9.0) | 11 (6.5) |

| 1 | 245 (71.0) | 126 (75.0) |

| 2 | 69 (20.0) | 31 (18.5) |

| Mean weight, kg (SD) | 67.6 (13.0) | 65.8 (13.5) |

| Weight loss over prior 6 months, n (%) | ||

| ≤10% of body weight | 209 (60.6) | 106 (63.1) |

| >10% of body weight | 136 (39.4) | 62 (36.9) |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 23.3 (3.6) | 22.8 (3.6) |

| Mean FAACT A/CS Domain score (SD) | 30.2 (8.3) | 30.2 (8.3) |

| Mean non-dominant handgrip strength, kg (SD) | 32.5 (11.5) | 32.2 (11.6) |

| Mean time from initial diagnosis, months (SD) | 18.2 (25.6) | 14.6 (21.2) |

| Overall stage at study entry, n (%) | ||

| IIIA | 34 (9.9) | 18 (10.7) |

| IIIB | 66 (19.1) | 35 (20.8) |

| IV | 244 (70.7) | 115 (68.5) |

| Missing | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Metastases at study entry, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 244 (70.7) | 115 (68.5) |

| No | 101 (29.3) | 53 (31.5) |

| Prior NSCLC treatment, n (%) | ||

| Chemotherapy/immunotherapy | 106 (30.7) | 46 (27.4) |

| Radiotherapy | 54 (15.7) | 23 (13.7) |

| Surgery | 66 (19.1) | 26 (15.5) |

| None | 196 (56.8) | 108 (64.3) |

| Concomitant therapya, n (%) | ||

| Chemotherapy/immunotherapy | 197 (57.1) | 98 (58.3) |

| Maintenance | 19 (5.5) | 11 (6.5) |

| Therapeutic | 181 (52.5) | 88 (52.4) |

| Adjuvant | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Radiotherapy | 41 (11.9) | 18 (10.7) |

ITT population. Baseline of the original trial was defined as the last measurement obtained prior to the first dose of the original trial study drug; for the extension trial, the baseline was defined as the last measurement obtained prior to the first dose of the extension trial study drug.

Concomitant chemotherapy/immunotherapy or radiation therapy included any chemotherapy/immunotherapy or radiation therapy used on or after the first dose date of the extension trial study drug and up to and including 7 days after the date of the last dose of the extension trial study drug.

BMI, body mass index; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; FAACT A/CS, Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Treatment Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale; ITT, intent-to-treat; NSCLC, non-small-cell lung cancer; SD, standard deviation.

TEAEs, study drug related or not, that occurred during the ROMANA 3 extension trial (12–24w) are shown in Table 2. Overall, 59 (11.6%) patients had an AE leading to death: 36 (10.5%) in the anamorelin group, and 23 (13.8%) in the placebo group. No death was considered study drug related (supplementary Table S5, available at Annals of Oncology online). The most common drug-related TEAE during ROMANA 3 was hyperglycemia (anamorelin: 1.2% versus placebo: 0.0%; Table 3). Four (1.2%) anamorelin-treated patients reported hyperglycemia, in weeks 4 or 12 of ROMANA 3 (corresponding to 16w and 24w). Two patients had grade 1 hyperglycemia (fasting glucose value higher than the upper limit of normal [ULN] of 160 mg/dl), possibly related to anamorelin; one patient had grade 2 hyperglycemia (fasting glucose value higher than the ULN of 160–250 mg/dl), possibly related to anamorelin. Hyperglycemia self-resolved without anamorelin dose alteration or medical intervention in each of the three patients. The fourth patient had grade 2 hyperglycemia deemed probably related to anamorelin on the ROMANA 3 week 4 visit (16 weeks). This patient received no hypoglycemic agents or dose alteration, and by study end (24 weeks) the fasting glucose value decreased below the ULN of 160 mg/dl (grade 1 hyperglycemia).

Table 2.

Summary of TEAEs (safety population) during the 12-week extension study (i.e. weeks 12–24 overall), whether related to study drug or not

| Adverse event category | ROMANA 3 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Anamorelin 100 mg | Placebo | |

| (n=343) | (n=167) | |

| TEAE, n (%) | ||

| ≥1 TEAE | 179 (52.2) | 93 (55.7) |

| ≥1 drug-relateda TEAE | 12 (3.5) | 2 (1.2) |

| ≥1 chemotherapy/immunotherapy- related TEAE | 93 (27.1) | 40 (24.0) |

| Patients with any grade 3–5 TEAE | 77 (22.4) | 36 (21.6) |

| Patients with any drug-relateda grade 3–5 TEAE | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.00) |

| Patients with any TEAE leading to discontinuation | 22 (6.4) | 11 (6.6) |

| Serious TEAEs, n (%) | ||

| ≥1 serious TEAE | 44 (12.8) | 21 (12.6) |

| ≥1 drug-related serious TEAE | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| TEAEs of special interest, n (%) | ||

| Blood glucose increased | 19 (5.5) | 6 (3.6) |

| Cardiovascular events | 13 (3.8) | 4 (2.4) |

| Ischemic heart disease | 4 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Electrocardiogram | 4 (1.2) | 7 (4.2) |

| Edema | 9 (2.6) | 5 (3.0) |

| Hepatic disorders | 22 (6.4) | 6 (3.6) |

| Deatha, n (%) | 36 (10.5) | 23 (13.8) |

No deaths were drug related.

TEAE, treatment–emergent adverse event.

Table 3.

Summary of study drug-related TEAEs by system organ class and preferred term (safety population)

| System organ class Preferred term | ROMANA 3 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Anamorelin 100 mg | Placebo | |

| (n=343) | (n=167) | |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Patients with any drug-related TEAEs | 12 (3.5) | 2 (1.2) |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 5 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hyperglycemia | 4 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 5 (1.5) | 1 (0.6) |

| Dry mouth | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Dyspepsia | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nausea | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Vomiting | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 3 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dermatitis bullous | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Onychomadesis | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Urticaria | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) |

| Fatigue | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Malaise | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Immune system disorders | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Allergic edema | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Investigations | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Increased γ-glutamyl transferase | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nervous system disorders | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Headache | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) |

TEAE, treatment–emergent adverse event (whether study drug-related to or not).

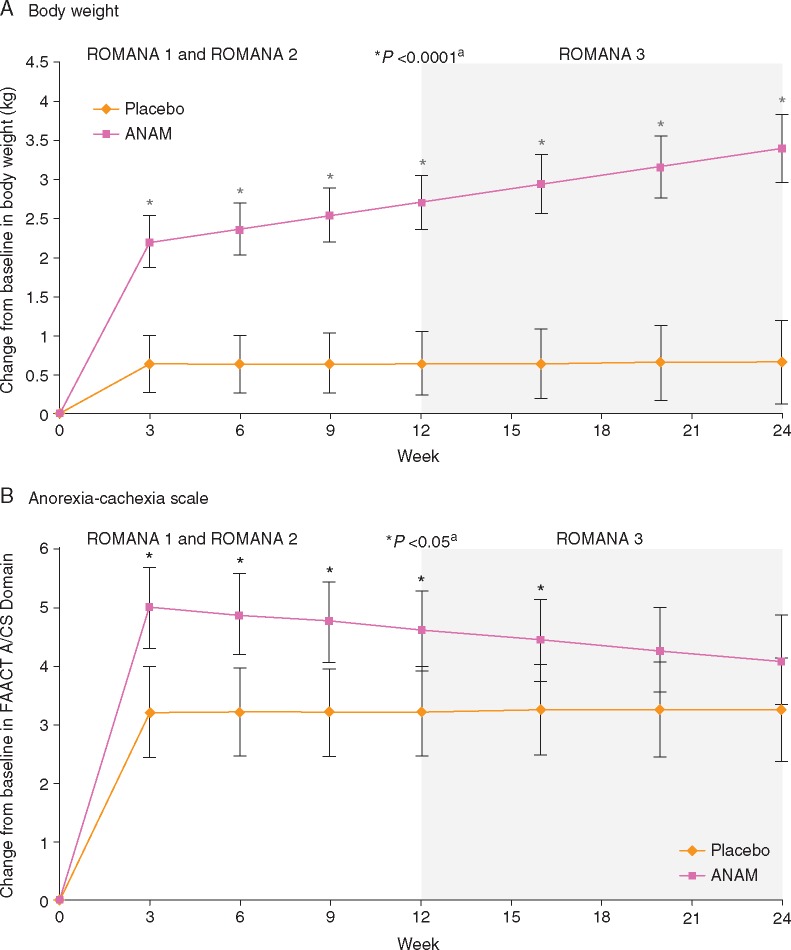

Over the 0–24w treatment period, body weight increased in the anamorelin (3.1 ± 0.6 kg; CI: 1.8, 4.3) versus the placebo (0.9 ± 0.7 kg; CI:−0.5, 2.3) group (treatment difference: 2.1 ± 0.5 kg; CI: 1.3, 3.0). Anamorelin versus placebo significantly improved body weight from baseline of original trials at all time points (Figure 2A; P <0.0001). During the 0–24 weeks treatment period, HGS worsened slightly in both groups (–0.8 ± 0.9 kg versus –0.6 ± 1.0 kg). The Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale score increased slightly more in the anamorelin (4.5 ± 0.9 [CI: 2.7, 6.3]) versus the placebo group (3.2 ± 1.0 [CI: 1.3, 5.2]; treatment difference: 1.2 ± 0.7 [CI: –0.1, 2.5]) over the 0–24w period, and also at all time points during 0–24w (Figure 2B), with significant treatment differences observed at weeks 3, 6, 9, 12, and 16 (P <0.05).

Figure 2.

Least-squares mean change (±SE) from baseline of original trials in (A) body weight and (B) FAACT Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale Domain Score during 24 weeks of treatment in patients enrolled in ROMANA 3. ITT population. aThe P value indicates a significant difference in body weight or FAACT Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale Domain Score between anamorelin- and placebo-treated patients from baseline of ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2 to each visit throughout the 0–24w treatment period and completion of extension trial (ROMANA 3) as part of the post-hoc analysis. A/CS, Anorexia/Cachexia Subscale; ANAM, anamorelin HCl; FAACT, Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Treatment; ITT, intent-to-treat; SE, standard error.

Analyzing changes in body weight and anorexia–cachexia symptoms according to age, gender, ECOG performance status, and BMI also suggested trends toward improvement following anamorelin treatment. Considering changes to body weight from 0 to 24w, treatment differences ranged from 1.0 to 2.7 kg across the different subgroups (anamorelin versus placebo) (supplementary Figure S1, available at Annals of Oncology online); for anorexia–cachexia symptoms, changes ranged from 0.6 to 2.2 points across subgroups (anamorelin versus placebo), except the >65 years subgroup, where the comparison favored placebo (supplementary Figure S2, available at Annals of Oncology online). Lastly, patients who continued in the ROMANA 3 safety extension trial had an improvement in mean body weight change from baseline of original trial (ROMANA 1 or ROMANA 2), whereas patients with a decrease in body weight change from baseline opted not to participate in ROMANA 3 (supplementary Figure S3, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Discussion

These results demonstrate that anamorelin is well tolerated in advanced NSCLC patients with cachexia over the 12–24w treatment period that constituted the ROMANA 3 safety extension study.

Anamorelin was well tolerated, and no new TEAEs were identified during ROMANA 3. Similar incidences of TEAEs, grade ≥3 TEAEs, and serious TEAEs, study drug un-/related, were reported for anamorelin versus placebo during the 12–24 weeks treatment period; drug-related TEAE incidence was 3.5% versus 1.2% (anamorelin versus placebo). The most common drug-related TEAE was hyperglycemia, which is consistent with ghrelin’s activity as a glucose metabolism regulator through multiple pathways [18]. It is perhaps surprising that hyperglycemia was not observed more frequently, given the positive energy balance and presumed increased carbohydrate intake in the anamorelin group, and considering that cachectic cancer patients tend to be insulin resistant [19]. The present results concur with those obtained in ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2 [14], where the most common drug-related TEAE reported was also hyperglycemia (ROMANA 1: 5.3%; ROMANA 2: 4.2%). Both trials also had low incidence of grade ≥3 drug-related TEAEs in the anamorelin group (0.9% and 2.7%, respectively) [16], while in ROMANA 3 no patient had any incidence of grade ≥3 drug-related TEAEs.

Over the entire 0–24 weeks treatment interval anamorelin, but not placebo, resulted in progressive increases in body weight in ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2 (0–12 weeks). Body composition analysis by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry confirmed that increases in LBM and fat mass accounted for the improvement in body weight [16]. Such changes may reflect a positive energy and protein balance, and are consistent with attenuation of anorexia–cachexia symptoms that could lead to increased food intake. In ROMANA 3, no serial body composition analysis was performed because it was considered an excessive patient burden. However, given that the rate of weight change was similar during the 0–12 weeks and 12–24 weeks treatment periods, it seems reasonable that body composition changes observed in ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2 would be maintained in ROMANA 3. In the placebo group no change from baseline in body weight over the 24 weeks period was observed. The lack of significant decrease in body weight in placebo-treated patients, which might be an expected outcome in NSCLC patients with cachexia, may at least partly be due to the good performance status of the majority of patients enrolled. The observed effect might also be due to the patients’ response to anti-cancer treatment. Regarding reduced anorexia–cachexia symptom burden leading to improved food intake, there appears to be no attenuation of effect based on body weight change at 24 weeks. The slight reduction in anamorelin-induced improvement on appetite/cachexia symptoms at weeks 20 and 24 is unlikely to have significant impact on food intake and energy balance. Alternatively, ghrelin receptor agonists may also increase body weight, independently from their effects on appetite, through other mechanisms such as decreased energy expenditure [20, 21]. Anamorelin effects were preserved in each of the age, gender, ECOG status, and BMI subgroup analyses. These effects were similar in all subgroups, despite the fact that ∼75% of patients enrolled in this study are males, a population with more pronounced weight loss due to cancer anorexia/cachexia. The lack of difference in anamorelin effect based on gender might be at least partly explained by the results of a phase I study performed in healthy volunteers [22]. This study indicated that gender played no significant differences in the pharmacodynamic responses of anamorelin (at a dose of 25 mg), as rapid and almost identical increases in circulating growth hormone levels were observed in both males and females following anamorelin administration. As such, a preponderance of males in the current study population does not appear to be clinically relevant with respect to treatment effect.

Current therapies for cancer anorexia–cachexia have limited efficacy and are associated with potential risks [23], particularly in patients with advanced cancer. Neither corticosteroids nor progestational agents increase LBM and, when given at high doses over long periods, corticosteroids are specifically associated with induction of frank muscle wasting. The shift to initiate anorexia–cachexia management early during the disease trajectory, to maintain improved QOL for a longer period [1], highlights the need for therapies that can be safely administered over relatively long intervals. In addition, treatments should also address nutrition, by increasing food intake and stimulating anabolism, and relieve symptom burden, by overcoming the cachexia-associated catabolic drive and enhancing body weight.

The incidence of drug-related TEAEs in ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2 was low and remained low after 24-week exposure to anamorelin in ROMANA 3. Thus, anamorelin appears suitable for longer-term cachexia interventions that might also include other modalities (e.g. exercise or nutritional support) [24]. These results are clinically relevant to patients with advanced-stage, metastatic disease, a population that undergoes significant cachexia-related weight loss [4]. In addition to improving the negative symptoms of cancer cachexia, the positive effects on body weight may help ease the emergent psychosocial distress associated with substantial weight loss [25].

ROMANA 3 does have limitations. No measurements of LBM or fat mass were taken, restricting conclusions about durability of anamorelin’s effect on body composition over longer time points. No measurements were performed to quantify patients’ caloric intake and no food diaries were collected, which limits inferences about anamorelin’s effect on food intake. Furthermore, not all patients who completed the ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2 trials entered in the ROMANA 3 extension study. This might be explained by the progression of disease to the extent to which the patient does not fulfill all eligibility criteria of the ROMANA 3 extension study, established prior to study initiation. Other possible explanations are patients’ own choice based on previous efficacy results with anamorelin or the possibility of selective attrition due to worsening health status, as would be anticipated in patients with advanced NSCLC. Deterioration of the health status may also obscure improvements in symptom burden. Another potential limitation of this study is the fact that NSCLC patients enrolled had a mean age of ∼62 years, somewhat younger than the typical lung cancer patient, aged 70 years or older [26, 27]. As such, that results of this study bear primary relevancy for slightly younger patients with NSCLC and a good performance status. Differences in patients recruitment rates between sites may also constitute a study limitation: the highest numbers of patients (>30 patients/site) were recruited at medical sites in Poland, Russia, Ukraine, and Hungary, while the lowest numbers were recruited at sites in the USA. A possible explanation for this discrepancy is the higher frequency of ongoing clinical studies in the USA in comparison with eastern European countries, thus leading to more possibilities for the patients and subsequently a lower enrollment rate.

In conclusion, in this safety extension trial of patients with an average age of 62 years, suffering from advanced-stage NSCLC and cachexia, anamorelin was well tolerated, exhibiting an AE profile similar to that in ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2, with no new safety signals identified. Improvements in body weight and anorexia–cachexia symptoms/concerns were consistently maintained for the 12–24 weeks extension period, demonstrating that anamorelin efficacy is maintained over a longer exposure period.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The trial was sponsored by Helsinn Therapeutics (U.S.). The authors would like to thank patients and investigators for their participation in this study. Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Oana Draghiciu, PhD and Joanne Franklin, PhD, CMPP (TRM Oncology, The Netherlands), and funded by Helsinn Healthcare SA. The authors are responsible for all content and editorial decisions.

Funding

This work was supported by Helsinn Therapeutics (U.S.), Inc. (no grant numbers apply).

Disclosure

AA is on the advisory board and on the board of directors of Flatiron Health. DC is on the advisory board of Helsinn. JF is an employee of Helsinn Therapeutics (U.S.), Inc. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Key Message

Treatment options for cancer anorexia–cachexia are limited despite its global recognition as a significant cause of morbidity. The ROMANA 3 safety extension study shows anamorelin’s safety and efficacy for a prolonged exposure period (24 weeks) in patients (mean age ∼62 years) with non-small-cell lung cancer, thus highlighting its potential as a novel, effective treatment option.

References

- 1. Fearon K, Strasser F, Anker SD. et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. Lancet Oncol 2011; 12: 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Von Haeling S, Anker SD.. Prevalence, incidence and clinical impact of cachexia: facts and numbers-update 2014. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2014; 5(4): 261–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fearon K, Arends J, Baracos V.. Understanding the mechanisms and treatment options in cancer cachexia. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013; 10: 90–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kimura M, Naito T, Kenmotsu H. et al. Prognostic impact of cancer cachexia in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Support Care Cancer 2015; 23(6): 1699–1708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Granda-Cameron C, DeMille D, Lynch MP. et al. An interdisciplinary approach to manage cancer cachexia. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2010; 14(1): 72–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davis MP. The emerging role of palliative medicine in the treatment of lung cancer patients. Cleve Clin J Med 2012; 79(electronic Suppl 1): eS51–eS55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wallengren O, Lundhlom K, Bosaeus I.. Diagnostic criteria of cancer cachexia: relation to quality of life, exercise capacity and survival in unselected palliative care patients. Support Care Cancer 2013; 21(6): 1569–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Guillory B, Splenser A, Garcia J.. The role of ghrelin in anorexia-cachexia syndromes. Vitam Horm 2013; 92: 61–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lundholm K, Gunnebo L, Korner U. et al. Effects by daily long term provision of ghrelin to unselected weight-losing cancer patients: a randomized double-blind study. Cancer 2010; 116(8): 2044–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hiura Y, Takiguchi S, Yamamoto K. et al. Effects of ghrelin administration during chemotherapy with advanced esophageal cancer patients: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Cancer 2012; 118: 4785–4794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Strasser F, Lutz TA, Maeder MT. et al. Safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of intravenous ghrelin for cancer-related anorexia/cachexia: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, double-crossover study. Br J Cancer 2008; 98: 300–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Currow DC, Abernethy AP.. Anamorelin hydrochloride in the treatment of cancer anorexia-cachexia syndrome. Future Oncol 2014; 10: 789–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garcia JM, Friend J, Allen S.. Therapeutic potential of anamorelin, a novel, oral ghrelin mimetic, in patients with cancer-related cachexia: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, crossover, pilot study. Support Care Cancer 2013; 21: 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garcia JM, Boccia RV, Graham CD. et al. Anamorelin for patients with cancer cachexia: an integrated analysis of two phase 2, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 108–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Temel J, Bondarde S, Jain M. et al. Efficacy and safety of anamorelin HCl in NSCLC patients: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre phase II study. Eur J Cancer 2013; 49(Suppl 2): S269–S270. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Temel JS, Abernethy AP, Currow DC. et al. Anamorelin in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer and cachexia (ROMANA 1 and ROMANA 2): results from two randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trials. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 519–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ribaudo JM, Cella D, Hahn EA. et al. Re-validation and shortening of the Functional Assessment of Anorexia/Cachexia Therapy (FAACT) questionnaire. Qual Life Res 2000; 9: 1137–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Heppner KM, Tong J.. Mechanisms in endocrinology: regulation of glucose metabolism by the ghrelin system: multiple players and multiple actions. Eur J Endocrinol 2014; 171: R21–R32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Honors MA, Kinzig KP.. The role of insulin resistance in the development of muscle wasting during cancer cachexia. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2012; 3: 5–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Murphy MG, Plunkett LM, Gertz BJ. et al. MK-677, an orally active growth hormone secretagogue, reverses diet-induced catabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83: 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Vestergaard ET, Djurhuus CB, Gjedsted J. et al. Acute effects of ghrelin administration on glucose and lipid metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Leese PT, Trang JM, Blum RA. et al. An open-label clinical trial of the effects of age and gender on the pharmacodynamics, pharmacokinetics and safety of the ghrelin receptor agonist anamorelin. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev 2015; 4(2): 112–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tuca A, Jimenez-Fonseca P, Gascón P.. Clinical evaluation and optimal management of cancer cachexia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2013; 88: 625–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fearon KC. Cancer cachexia: developing multimodal therapy for a multidimensional problem. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44: 1124–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rhondali W, Chisholm GB, Daneshmand M. et al. Association between body image dissatisfaction and weight loss among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers: a preliminary report. J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 45: 1039–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Makrantonakis PD, Galani E, Harper PG.. Non-small cell lung cancer in the elderly. Oncologist 2004; 9: 556–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Maione P, Rossi A, Sacco PC. et al. Treating advanced non-small cell lung cancer in the elderly. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2010; 2(4): 251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.